The Definitives

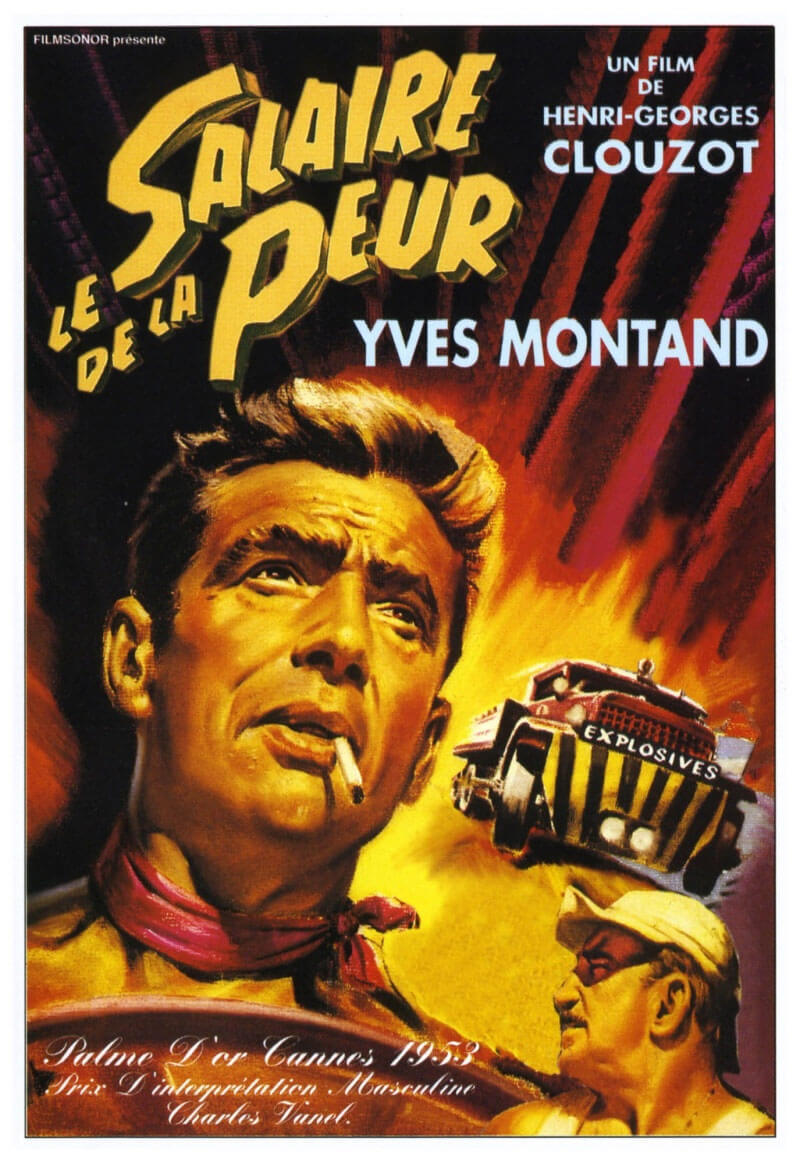

The Wages of Fear (1953)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Opening on a boy torturing cockroaches in the street, The Wages of Fear’s first shot expounds the entire film. Deprived, the child suddenly follows after a shaved-ice merchant pushing his cart and announcing flavors. The boy longs for that which he cannot afford and upon realizing this he returns to his roaches, finding a vulture has claimed his afternoon entertainment. Within hopeless situations such as this, Henri-Georges Clouzot constructed films of incredible suspense, harsh commentary, and unforgiving cynicism; these are all evident in his agonizing portrayal of human nature, his 1953 masterpiece The Wages of Fear (Le Salaire de la peur). Clouzot was perhaps the best French filmmaker from his era, earning a place alongside names in the French canon like Jean Renoir, Jacques Tati, and Max Ophüls. Probing into his disillusionment with human nature, he explored how we rarely live up to our own promise, and within The Wages of Fear, presents an antitheses for human potential. Ahead of his existential subject, however, Clouzot’s film embodies the arrangement and execution of a draining white-knuckle thriller—a work of art that challenges the viewer’s sense of insight into its characters, or potential saddening apathy to dismiss them.

Clouzot’s film confronts us with more than merely a brief anecdotal setup, but an in-depth examination of his focus—four tramps paid $2,000 a piece by an American oil company to haul two truckloads of nitroglycerin across desolate, volatile terrain, to blow out a smoldering drill site. Laid to waste in the squalid and impoverished South American village of Las Piedras, Clouzot’s four drivers are painted deliberately unpleasant and yet curiously sympathetic. Each is dead-broke, jobless, skulking about, waiting for an opportunity to get out of their own hell. They are not heroes, otherwise their station would not be begging for work in a muddy village; these men have long since helped their own cause. And yet, they are the film’s “heroes” in the narrative sense that they are protagonists, thus we care about their fates. Clouzot’s four men—Frenchmen Mario (Yves Montand) and Jo (Charles Vanel), the Italian Luigi (Folco Lulli), and the German Bimba (Peter Van Eyck)—similarly take a fleeting, hopeless look at the impossible opportunity presented to them by the American oil company stationed in the village, and find everything they have hence taken away.

Back in the first scene in the streets, all at once a jeep marked SOC, for Southern Oil Company, passes through, tearing into the grimy puddles. Without an inkling of subtlety, Clouzot changes “Standard” to “Southern” and secures himself a thinly veiled target in America’s monopolizing multinational oil corporation Standard Oil, its initials identical. Later we meet Bill O’Brien (William Tubbs), the local Yankee foreman of SOC who resolves to hire vagrants instead of union men to drive the unstable, doomed-to-explode trucks to the blazing rig site. “Those bums don’t have any union, nor any families,” he says. “And if they blow up, nobody’ll come around bothering me for any contribution.” Not only does Clouzot’s anti-American picture take an unabashed stab at the heartless greed of Western oil mongering, but it also questions those who would give up their lives to such a despairing cause. Clouzot explained, “It’s a film about men. I’d never made a film in which the drama was entirely confined in male characters.” Loafing amid the poverty of Las Piedras, nearly an hour of the film passes before the four men resign themselves to SOC’s suicide mission.

Back in the first scene in the streets, all at once a jeep marked SOC, for Southern Oil Company, passes through, tearing into the grimy puddles. Without an inkling of subtlety, Clouzot changes “Standard” to “Southern” and secures himself a thinly veiled target in America’s monopolizing multinational oil corporation Standard Oil, its initials identical. Later we meet Bill O’Brien (William Tubbs), the local Yankee foreman of SOC who resolves to hire vagrants instead of union men to drive the unstable, doomed-to-explode trucks to the blazing rig site. “Those bums don’t have any union, nor any families,” he says. “And if they blow up, nobody’ll come around bothering me for any contribution.” Not only does Clouzot’s anti-American picture take an unabashed stab at the heartless greed of Western oil mongering, but it also questions those who would give up their lives to such a despairing cause. Clouzot explained, “It’s a film about men. I’d never made a film in which the drama was entirely confined in male characters.” Loafing amid the poverty of Las Piedras, nearly an hour of the film passes before the four men resign themselves to SOC’s suicide mission.

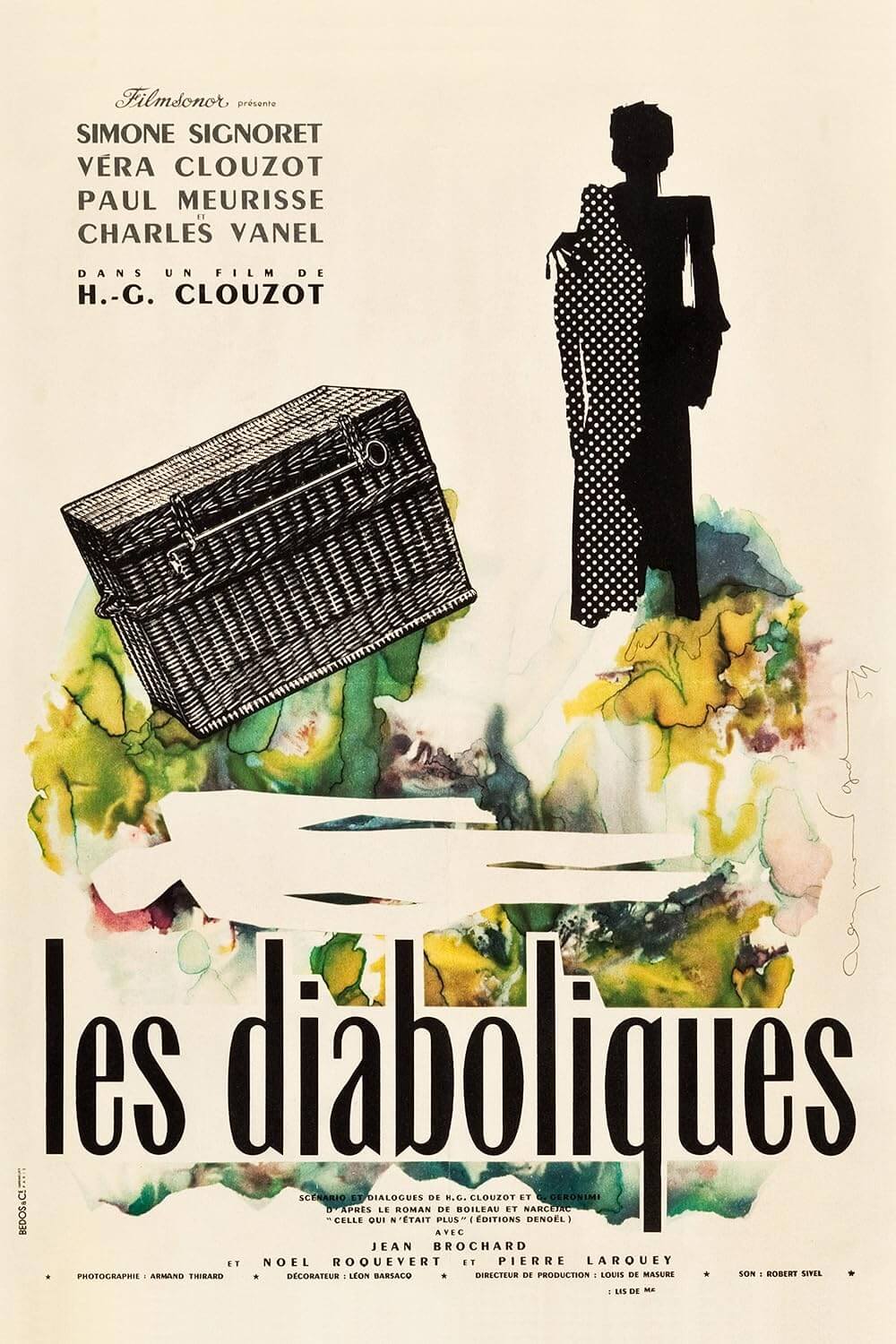

In that time, Clouzot avoids establishing backstories and instead outlines the contemptible manner in which each man fails to see what lies in front of him. In Mario’s case, he overlooks the film’s one female character and his own love interest, Linda, played by the director’s wife, Véra Clouzot. She seems to pant like a dog for Mario’s affections, quite literally crawling on all fours to greet him, though her doting love is not returned in favor of a senseless opportunity, which represents itself to Mario in the form of Jo, a would-be well-to-do. Jo puts on airs, but he’s in the same sinking boat as everyone else in Las Piedras. Perhaps an inkling of reserved homosexuality leads to Mario’s mistreatment of Linda, as many scholars have proposed. Indeed, the relationships between the four drivers in Clouzot’s film are close, but no direct instance or line of dialogue confirms that label. Some have suggested Clouzot is simply a chauvinist, but no. Rather, look at Mario’s disregard for Linda as a testimony to his blind longing to find something else besides a resigned life with a poor girl, besides just making it in Las Piedras. Mario and the others do not accept their fates; they fight, however fruitlessly, for something better. They have no idea of what that might be, and so anyone not bent on forward motion drags them behind, woman or otherwise. If so, there is meaning behind Clouzot casting his wife in the role of Linda. He shoots her from two conflicting subjective points of view: from that of a husband depicting his wife’s beauty, and that of a director placing an actress in a narrative. Clouzot ensures his wife’s face is always clean, even when she falls in the mud, and her neckline remains low and revealing. And yet, her character is treated like an animal. She is wholly obedient and subservient—a typical, uncomplicated male fantasy. Still, Mario tosses her aside. Inside Mario’s rejection, Clouzot delineates the fatalistic drive pushing Mario and his fellow drivers to ignore the value of their current lives for the potential of the mythical greener grass. Furthermore, for Clouzot, given his adoration for Véra, whom he would next cast in the starring role of Les Diaboliques (1955), such a refusal must have denoted insanity to snub a woman he dearly loved offscreen.

Often criticized for their scarce amiability, the characters in The Wages of Fear are themselves a test to pierce emotionally. By writing his drivers as lowlifes on margins, far removed from normal society and filled with desperation, thereby deleting any romantic portrayals, Clouzot orchestrates an exercise in human empathy, in the audience’s ability to find compassion for the fates of inexcusably harsh men. Author Dennis Lehane keenly observed, “This erasure of sentiment does not cancel out empathy. In fact, in that very voice, we, the viewer, are forced to decide what our capacity for empathy is.” During the 1930s, the twentysomething Clouzot spent four years in a tuberculosis sanatorium, watching those like him suffer and eventually fade away while he recovered from a near-death bout. The realness of morality was all around him there, a place his biographers consider the incubator for his brooding tone and his profound understanding of the complexities and limitations of both life and death. Clouzot’s prolonged experience imbued him with an appreciation of life, therefore, within The Wages of Fear, his four drivers, who value their lives so little that they would transport and are bound to die by the SOC’s volatile nitro, are represented as contemptible heroes hurdled by an inescapable death drive.

Often criticized for their scarce amiability, the characters in The Wages of Fear are themselves a test to pierce emotionally. By writing his drivers as lowlifes on margins, far removed from normal society and filled with desperation, thereby deleting any romantic portrayals, Clouzot orchestrates an exercise in human empathy, in the audience’s ability to find compassion for the fates of inexcusably harsh men. Author Dennis Lehane keenly observed, “This erasure of sentiment does not cancel out empathy. In fact, in that very voice, we, the viewer, are forced to decide what our capacity for empathy is.” During the 1930s, the twentysomething Clouzot spent four years in a tuberculosis sanatorium, watching those like him suffer and eventually fade away while he recovered from a near-death bout. The realness of morality was all around him there, a place his biographers consider the incubator for his brooding tone and his profound understanding of the complexities and limitations of both life and death. Clouzot’s prolonged experience imbued him with an appreciation of life, therefore, within The Wages of Fear, his four drivers, who value their lives so little that they would transport and are bound to die by the SOC’s volatile nitro, are represented as contemptible heroes hurdled by an inescapable death drive.

That Clouzot’s protagonists select a fatalistic mission makes the road no less daunting, or involving, or thrilling for the viewer. Split between two trucks, the men divide themselves as an insurance policy. Should one truck suddenly detonate, the other could still make it through. Mario and Jo take the lead, with Luigi and Bimba following a half an hour behind. Each man is stripped down to the barest version of himself once on the road, as fear removes layer after layer of built-up fronts, disrobing him until nothing is left but the raw man. Herein we see where some endure and others fall to pieces. Charles Vanel’s performance as Jo is the film’s best illustration of this; his character loses the most, having masqueraded himself as a brave, experienced workman to hide his cowardly interior. Clouzot originally hoped to fill the role with France’s equivalent to Humphrey Bogart, Jean Gabin from Grand Illusion (1937) and Touchez pas au grisbi (1954), but the screen icon turned down the role, worried that playing a coward might tarnish his onscreen reputation. Furthermore, surely Gabin would have stolen the picture away from Yves Montand in the central role by presence alone; whereas Vanel, who disappears into his harrowing performance, committing himself to the depths of spinelessness and turmoil the role demands.

As the trucks commence on their voyage, their first test is a stretch of aptly named road called “the washboard,” on which the trucks must either slog or race over to avoid rough handling of the nitroglycerin. Jo makes every excuse to convince Mario to take the slower route, and after driving for the first twenty miles, allows the rear truck to pass, by taking it slow, complaining of nausea, stalling, all the while petrified with fear. Vanel’s performance is subtle, shaky, and gripping, and gruelingly real when Mario races across. Meanwhile, Mario no longer looks up to Jo, having become hard-bitten by the experience and his desire for money. Suspense dwells in possibility as opposed to visible action, suggestion versus appearance. Clouzot simply gives the viewer knowledge that should the drivers hit a particularly deep bump or rattle the truck with too much force, the nitro goes off. Once on the road, the strain never subsides. Elaborate set-ups are employed for their suspense, but also their emotional reflection. Therein resides the ever-pumping engine of the film. Yves Montand is the film’s other engine. Not yet the screen legend he would later become from pictures like Grand Prix (1966) and Le Cercle rouge (1970), Clouzot cast the young actor because he was relatively inexperienced onscreen, and therein could be shaped. Clouzot considered actors to be moldable like clay—akin to Hitchcock’s famous quip that actors are cattle—and did not limit himself by catering to their needs. Filming in Brazil and shot with a minor crew, the tyrannical director strains every authentic bead of sweat and frustration and virile emotion from Montand. The resulting performance lends each line of dialogue a rich text of self-loathing, anger, and despondency, reaching their pinnacle in the story’s demanding chain of setups.

As the trucks commence on their voyage, their first test is a stretch of aptly named road called “the washboard,” on which the trucks must either slog or race over to avoid rough handling of the nitroglycerin. Jo makes every excuse to convince Mario to take the slower route, and after driving for the first twenty miles, allows the rear truck to pass, by taking it slow, complaining of nausea, stalling, all the while petrified with fear. Vanel’s performance is subtle, shaky, and gripping, and gruelingly real when Mario races across. Meanwhile, Mario no longer looks up to Jo, having become hard-bitten by the experience and his desire for money. Suspense dwells in possibility as opposed to visible action, suggestion versus appearance. Clouzot simply gives the viewer knowledge that should the drivers hit a particularly deep bump or rattle the truck with too much force, the nitro goes off. Once on the road, the strain never subsides. Elaborate set-ups are employed for their suspense, but also their emotional reflection. Therein resides the ever-pumping engine of the film. Yves Montand is the film’s other engine. Not yet the screen legend he would later become from pictures like Grand Prix (1966) and Le Cercle rouge (1970), Clouzot cast the young actor because he was relatively inexperienced onscreen, and therein could be shaped. Clouzot considered actors to be moldable like clay—akin to Hitchcock’s famous quip that actors are cattle—and did not limit himself by catering to their needs. Filming in Brazil and shot with a minor crew, the tyrannical director strains every authentic bead of sweat and frustration and virile emotion from Montand. The resulting performance lends each line of dialogue a rich text of self-loathing, anger, and despondency, reaching their pinnacle in the story’s demanding chain of setups.

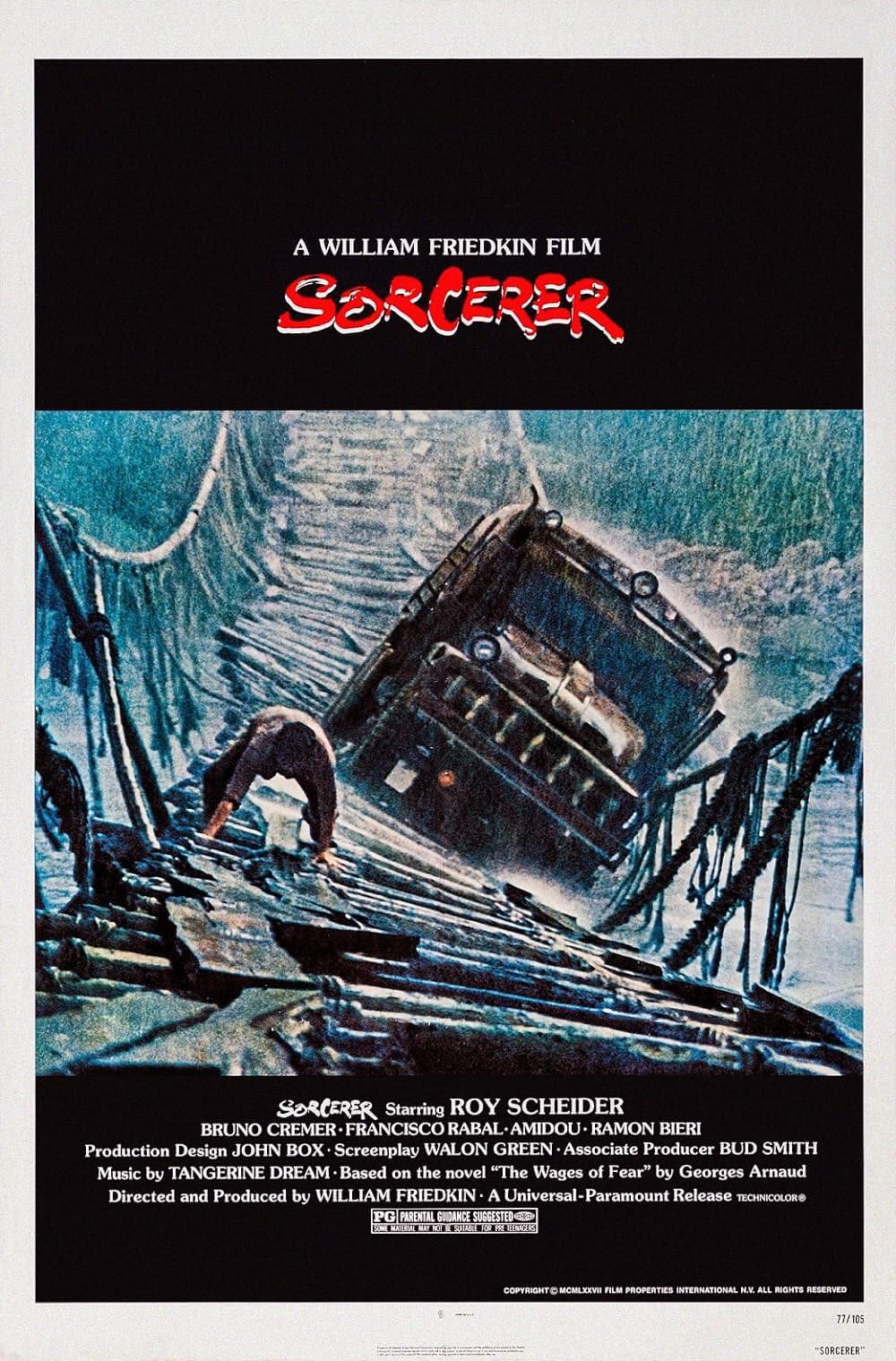

Such trials include an abrupt turn the trucks can only get around by backing onto a rickety platform of rotting wood dangling over a rocky chasm. Later, a boulder in the road must be removed by detonating a thermos-full of nitro. Each of these sequences is accomplished with temperance and nerve-racking precision by Clouzot. In the film’s most calm, genial moment, Jo rolls Mario a cigarette as they shove along. All at once a flash, the tobacco is blown from Jo’s paper—up ahead, a dusty mushroom cloud fills the air. The other truck is gone. Clouzot has delivered his punch. These masterful strokes are only outdone by Alfred Hitchcock himself, who Clouzot undercut twice in his career when attempting to secure rights for filmic properties—first with The Wages of Fear, second with Les Diaboliques. Hitchcock had attempted to buy the rights to both films, and in both cases, the French director prevailed, first because author Georges Arnaud preferred to have a French filmmaker adapt his novel, second because Hitchcock’s bid came a mere few hours too late. The two directors are inescapably linked by their ability to force their respective audiences to the breaking point of suspense. Though, Hitchcock’s oeuvre is clearly the more fertile and was not met with the same thematic criticism of Clouzot’s fiercely controversial subjects.

In his early days, Clouzot’s directorial career flourished just before Germany invaded France, and despite the dangerous political environment, he refused to silence his art. He was caught between the horrors of the Nazis’ genocide and the realization that the Vichy government did little to stop it and so deserved accusations of collaboration. Releasing Le Corbeau in 1941, Clouzot was considered reactionary to French informants to the Nazi regime, as the film concerns a village plagued by the author of poison pen letters divulging the citizens’ secrets, dismantling the town in the process. Banned in France until after WWII, the film was the first of many Clouzot pictures teaming with merciless commentary. Surprisingly, The Wages of Fear’s unyielding anti-American stance did not result in the picture being banned in the United States; rather, in 1955 the U.S. distributor simply edited out any controversial content. Eliminating any perceived anti-Americanism or hints of homosexuality by cutting nearly fifty minutes of footage, distributors cut scenes almost exclusively from the first act, before the nitro-haul begins, claiming their decision was based on the film’s length. Within the cut scenes, Clouzot establishes SOC as the local villains of Las Piedras and shows an international community to be victims of Western capitalism. Brazen anti-American dialogue like, “If there’s oil around, they’re not far behind,” was altogether removed. The contemptuous depiction of O’Brien, the American boss readily sending tramps to their deaths, was trimmed. Not until 1992, after the political fervor inspiring the ruthless editing job had passed, was the film restored to its original and uncut form.

In his early days, Clouzot’s directorial career flourished just before Germany invaded France, and despite the dangerous political environment, he refused to silence his art. He was caught between the horrors of the Nazis’ genocide and the realization that the Vichy government did little to stop it and so deserved accusations of collaboration. Releasing Le Corbeau in 1941, Clouzot was considered reactionary to French informants to the Nazi regime, as the film concerns a village plagued by the author of poison pen letters divulging the citizens’ secrets, dismantling the town in the process. Banned in France until after WWII, the film was the first of many Clouzot pictures teaming with merciless commentary. Surprisingly, The Wages of Fear’s unyielding anti-American stance did not result in the picture being banned in the United States; rather, in 1955 the U.S. distributor simply edited out any controversial content. Eliminating any perceived anti-Americanism or hints of homosexuality by cutting nearly fifty minutes of footage, distributors cut scenes almost exclusively from the first act, before the nitro-haul begins, claiming their decision was based on the film’s length. Within the cut scenes, Clouzot establishes SOC as the local villains of Las Piedras and shows an international community to be victims of Western capitalism. Brazen anti-American dialogue like, “If there’s oil around, they’re not far behind,” was altogether removed. The contemptuous depiction of O’Brien, the American boss readily sending tramps to their deaths, was trimmed. Not until 1992, after the political fervor inspiring the ruthless editing job had passed, was the film restored to its original and uncut form.

More than its politics, Clouzot’s film is an antithetical figurehead for every optimistic or romanticized story ever told. His pessimism seems to bleed from the screen, particularly after just the one truck remains. Mario and Jo approach where their fellow drivers exploded and find wiped-out trees, a gaping crater, and a broken oil pipe gradually making the hole into a dense, slippery lake. Fed up with Jo’s peaking fear, Mario sends him into the oil lagoon to check its depth and creeps behind in the truck, unable to stop for fear of getting trapped. Jo suddenly finds himself stuck by a submerged tree branch, powerless to get free, and driving Mario cannot slow, and so at a seemingly deliberate pace, grinds the wheels over his partner’s leg, crushing it. Vanel, coated in oil, is a black ghost screaming in pain. Back on the road after winching the truck out of their slippery hovel, both men are covered in slick, and Jo is dying. Minutes before reaching their destination, he passes, leaving Mario the only survivor of the four.

Clouzot’s ending should be happy, as we have followed Mario from the beginning, and having cheated death under impossible circumstances, he now drives back to Las Piedras with double the booty including Jo’s forfeited pay. A Strauss waltz rings over intercut scenes of Mario’s joyful, void-of-danger return drive home and Linda celebrating his homecoming. Linda dances in elation, her love for Mario not tarnished in the least from his desertion; Mario intentionally swerves back and forth on the road with careless merriment, free from the nitroglycerin’s threat. But his veering becomes too wide, the railing at too sharp a turn, and Mario goes over the edge. The truck destroyed in a blaze of irony, “Fin” appears over the last shot of our bloodied hero. Certainly, the brutal narrative cynicism and political commentary in The Wages of Fear indicate the unflinching nature of its maker. On set, Henri-Georges Clouzot took the dictator-director role played by many auteurs, leaving him thought of as “A tough cookie.” But Clouzot is not void of hope, nor is his message misanthropic, though critics of his film might suggest otherwise. Described through an obstinate set of dramatic criteria, his film reproaches those who blame abstractions such as “fate” and “life” for their troubles, when Clouzot would argue it is we who create the world we live in. Propelling their own outcomes, his drivers press on willingly, contentiously, and throughout, opt for death at every inch of ground gained. For Clouzot, these are the choices made by a wasted life.

Clouzot’s ending should be happy, as we have followed Mario from the beginning, and having cheated death under impossible circumstances, he now drives back to Las Piedras with double the booty including Jo’s forfeited pay. A Strauss waltz rings over intercut scenes of Mario’s joyful, void-of-danger return drive home and Linda celebrating his homecoming. Linda dances in elation, her love for Mario not tarnished in the least from his desertion; Mario intentionally swerves back and forth on the road with careless merriment, free from the nitroglycerin’s threat. But his veering becomes too wide, the railing at too sharp a turn, and Mario goes over the edge. The truck destroyed in a blaze of irony, “Fin” appears over the last shot of our bloodied hero. Certainly, the brutal narrative cynicism and political commentary in The Wages of Fear indicate the unflinching nature of its maker. On set, Henri-Georges Clouzot took the dictator-director role played by many auteurs, leaving him thought of as “A tough cookie.” But Clouzot is not void of hope, nor is his message misanthropic, though critics of his film might suggest otherwise. Described through an obstinate set of dramatic criteria, his film reproaches those who blame abstractions such as “fate” and “life” for their troubles, when Clouzot would argue it is we who create the world we live in. Propelling their own outcomes, his drivers press on willingly, contentiously, and throughout, opt for death at every inch of ground gained. For Clouzot, these are the choices made by a wasted life.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review