The Definitives

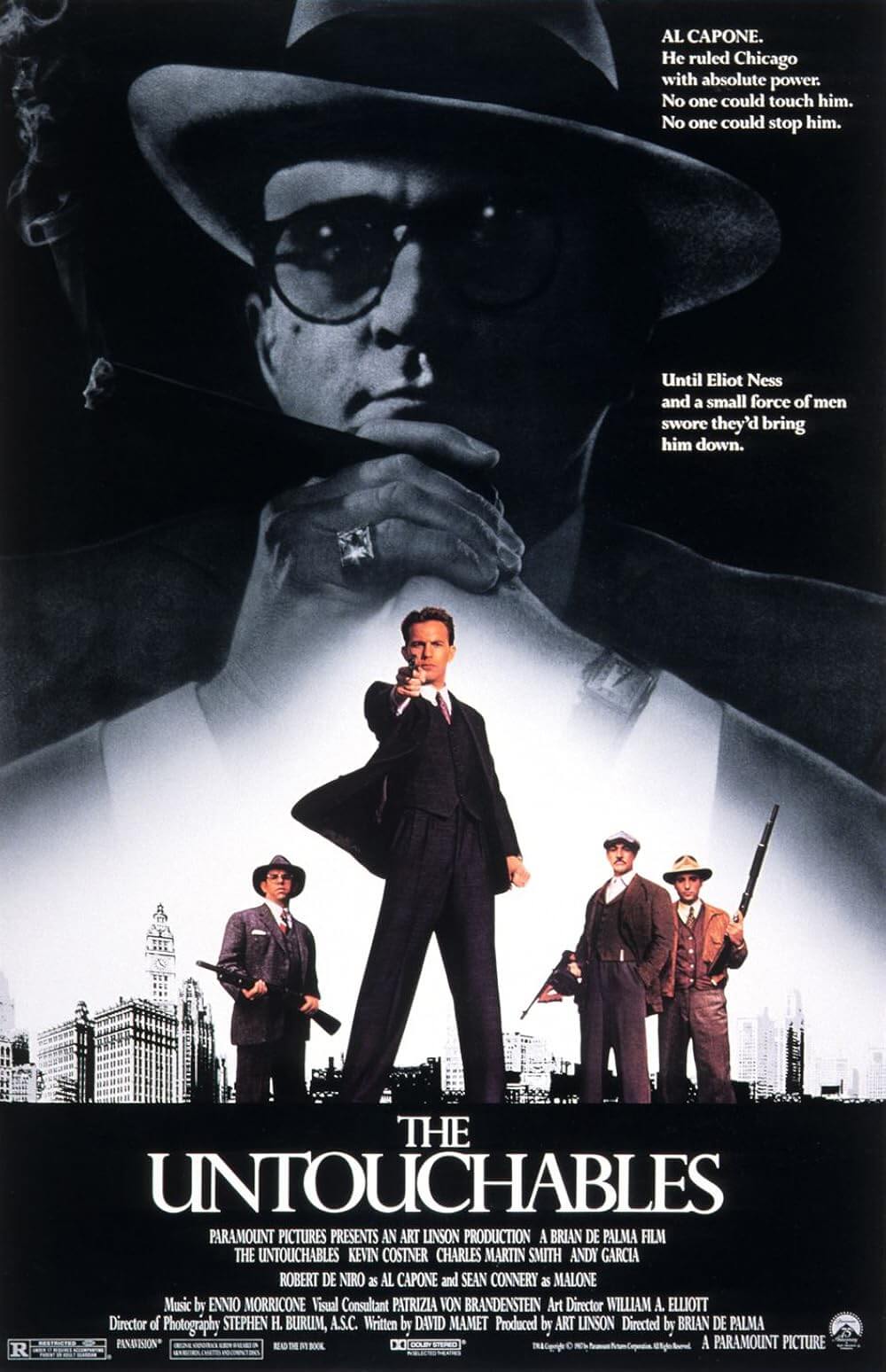

The Untouchables (1987)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

An early scene in The Untouchables sets the stage for how director Brian De Palma establishes a nostalgic idyll, and then shatters it throughout the film. In 1930, just under the El train in Chicago’s Wrigleyville, a ten-year-old girl crosses the street into a corner pub to fetch milk in her mother’s bucket. Ford Model Ts pass on the street, a traincar runs overhead, and a few scattered pedestrians populate the sidewalks. It’s a sublime recreation of old Chicago. Inside, the girl waits at the counter as the owner finishes his conversation with a man, saying he wants no “green beer” for his pub. When the owner finishes, he fills the girl’s bucket and asks about her mother, but she notices another man in a white suit has just left his briefcase behind. “Mister!” she shouts. “You forgot your briefcase!” The man in the white suit slithers away in a rush. All at once, this scene reminds us of Alfred Hitchcock’s Sabotage from 1936, and the young boy who unknowingly carried a bomb before it exploded, and our stomach drops. Standing in the doorway, holding the briefcase, the girl, along with the pub, detonate into a blaze. This is indeed a scene straight out of old Chicago in 1930, the most violent city of the Prohibition era, just before the repeal of the Volstead Act. The next morning, Catherine Ness finishes packing her husband’s lunch and approaches him in their den. He reads the headline about the bombing. She tells him, “Now it’s time to go to work” and kisses him goodbye.

Released in 1987, De Palma’s film captures our reminiscences for an era that Hollywood has since glamorized in the minds of audiences. It was a time that never existed: when good and evil were clearly drawn opposites, and the heroes always stopped the bad guys, no matter how fascinating the gangster lifestyle happened to be. Shortly after Eliot Ness brought down Prohibition mobster Al Capone, stories about Ness’ group of handpicked, incorruptible “Untouchables” became the stuff of romanticized storytelling. Americans invited these stories into their homes from 1959 to 1963 with an ABC television series of the same name, starring Robert Stack as Ness. Based on the 1957 book, which Ness co-wrote with Oscar Fraley, the film reinforces those dreamy visions of Ness’ heroism, even while De Palma and screenwriter David Mamet deconstruct the black-and-white conflict and complicate the moral stakes. De Palma and Mamet serve as iconoclasts, suggesting this was not a battle between good and evil; rather, it was a battle in which Ness was forced to become more like Capone in order to defeat him. The Untouchables remains an uncommon sort of gangster drama, aesthetically supporting the Hollywood vision of a glamorous era of attractive violence, and then thematically tearing that vision apart.

Paramount Pictures, who owned the rights to The Untouchables television series, put producer Art Linson in charge of developing the film. Linson’s first choice of director was De Palma, for whom The Untouchables represented a crucial point in his career. De Palma’s last two films, Body Double (1984) and Wise Guys (1986), flopped at the box-office, and he needed something that would show the studios he could direct a profitable picture. Only then could De Palma once again explore his more independent, personal features (such as Blow Out or Dressed to Kill). “In Hollywood, three strikes and you’re out,” he told Linson. The producer also hired his first choice of writer, David Mamet, who earned an Oscar in 1983 for his work on The Verdict and wanted the material to be independent of the television series. Mamet instead revisited Ness’ original text, incorporating actual accounts of the Untouchables into the screen story and, being a Chicagoan, he included some of his own research. When Paramount officially offered De Palma directing duties, the studio entrusted him with a $20 million budget, and much of it was spent on the cast.

Paramount Pictures, who owned the rights to The Untouchables television series, put producer Art Linson in charge of developing the film. Linson’s first choice of director was De Palma, for whom The Untouchables represented a crucial point in his career. De Palma’s last two films, Body Double (1984) and Wise Guys (1986), flopped at the box-office, and he needed something that would show the studios he could direct a profitable picture. Only then could De Palma once again explore his more independent, personal features (such as Blow Out or Dressed to Kill). “In Hollywood, three strikes and you’re out,” he told Linson. The producer also hired his first choice of writer, David Mamet, who earned an Oscar in 1983 for his work on The Verdict and wanted the material to be independent of the television series. Mamet instead revisited Ness’ original text, incorporating actual accounts of the Untouchables into the screen story and, being a Chicagoan, he included some of his own research. When Paramount officially offered De Palma directing duties, the studio entrusted him with a $20 million budget, and much of it was spent on the cast.

Sean Connery had been attracted to the production because of Mamet, then a Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright for Glengarry GlenRoss. Moreover, Connery’s character Malone was a juicy supporting role, filled with quotable, tough dialogue. For Capone, De Palma desperately wanted Robert De Niro (Bob Hoskins was his backup choice); the two had worked together in the 1960s on several small features (The Wedding Party, Greetings, and Hi, Mom!), prior to De Niro’s surge in popularity and high critical praise. The actor would put on twenty-five pounds, raise his hairline, and wear a body suit for the role, showing a more contented, girthy Capone. As the rest of the cast fell into place, De Palma interviewed several actors for the role of Ness, his first choice being Mel Gibson, who had a scheduling conflict due to Lethal Weapon. At the time, Kevin Costner wasn’t yet a star. He impressed in Silverado (1985), but De Palma was reluctant to hire him. Nevertheless, after a single meeting, Linson was convinced Costner was the right choice. The gamble paid off, as Costner was the glue that brought the ensemble together. After the film’s release in June of 1987, The Untouchables earned $76 million in domestic receipts, thus reestablishing De Palma in the eyes of Hollywood. The film went on to earn several Academy Award nominations (for Best Score, Best Costume Design, and Best Art Direction-Set Decoration), but only Connery won for Best Supporting Actor.

Even the few critics who walked away from The Untouchables unmoved gave the film credit for its lavish appearance, from Stephen H. Burum’s slick camerawork to Marilyn Vance’s costumes designed by Georgio Armani. Production designers Patrizia von Brandenstein, William A. Elliott, and Hal Gausman took great care to realize De Palma’s glamorization of the era, ornamenting every set not only with period detail, but with a visual sense that masterfully considers the decoration and architecture of a given set. Throughout the film, characters begin to take on the larger-than-life personalities of their surroundings—the vaulted ceilings, ornate walls, and mannerist styles. Several low angles look upward, at once capturing the extravagant splendor of the interiors and aggrandizing the subjects in the scene. The backdrops not only reflect the decadent lifestyles of Chicago’s most ruthless mobster, but also the domestic wallpaper in Ness’ rather quaint, virtuous home, right down to the shabby earthiness found in the apartment owned by Ness’ mentor, Malone. The film had been designed to show this era not as it was, but as we imagine it was.

Even the few critics who walked away from The Untouchables unmoved gave the film credit for its lavish appearance, from Stephen H. Burum’s slick camerawork to Marilyn Vance’s costumes designed by Georgio Armani. Production designers Patrizia von Brandenstein, William A. Elliott, and Hal Gausman took great care to realize De Palma’s glamorization of the era, ornamenting every set not only with period detail, but with a visual sense that masterfully considers the decoration and architecture of a given set. Throughout the film, characters begin to take on the larger-than-life personalities of their surroundings—the vaulted ceilings, ornate walls, and mannerist styles. Several low angles look upward, at once capturing the extravagant splendor of the interiors and aggrandizing the subjects in the scene. The backdrops not only reflect the decadent lifestyles of Chicago’s most ruthless mobster, but also the domestic wallpaper in Ness’ rather quaint, virtuous home, right down to the shabby earthiness found in the apartment owned by Ness’ mentor, Malone. The film had been designed to show this era not as it was, but as we imagine it was.

Consider how The Untouchables opens with an overhead shot looking down on Al Capone in a barber’s chair, a throne resting on a parqueted floor decorated in sun-like orbs. De Palma builds up Capone, comparing him to Louis XIV. “He’s the Sun King,” said the director. “Everybody sits and waits for the master, the man of power, the man that runs the world, the god that’s at the center of the universe.” Around Capone, attendants give him a manicure, shine his shoes, and prepare him for a shave; another four men stand on guard, while two members of the press chuckle over Capone’s eloquent retorts. In De Palma’s hands, Capone is surrounded by opulence, bright red carpeting, stucco ceilings, golden trim, walnut wood, and he takes his breakfast on a huge Victorian bed. He’s far removed from other depictions of the character, such as Stephen Graham’s harsh, numb-skulled version on HBO’s series Boardwalk Empire (2010-2014). De Niro’s role certainly projects more grandiosity than another character based on Capone: Scarface, first realized in the 1932 pre-code film by Howard Hughes and Howard Hawks, and later in a frenzied remake by De Palma himself. Mamet’s screenplay renders Capone capable of wooing the press, often in the writer’s Mametspeak: “Somebody messes with me, I’m gonna mess with him. Somebody steals from me, I’m gonna say you stole, not talk to him for spitting on the sidewalk. Understand? …Now, I have done nothing to harm these people but they are angered with me, so what do they do, doctor up some income tax, for which they have no case. To speak to me like me—no—to harass a peaceful man. I pray to god if I ever had a grievance I’d have a little more self-respect.”

Opposite Capone stands Treasury Department agent Eliot Ness, who at first is naïve to the corruption of Chicago. After Capone’s men are tipped-off to Ness’ first raid, he resolves to recruit a squad of clean, incorruptible policemen. He seeks out Malone, an honest, but experienced beat cop, for guidance. De Palma shoots the scenes in which Ness and Malone assemble their Untouchables mindful of a similar sequence from John Sturges’ The Magnificent Seven (1960). He even instructed Ennio Morricone to evoke the composer’s own scores on films like Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) in the music for The Untouchables, resulting in an echoing harmonica that arouses a kind of Western atmosphere. Ness and Malone acquire George Stone (Andy Garcia), an Italian sharpshooter still working his way through the academy. They also bring along the nebbish federal accountant Oscar Wallace (Charles Martin Smith), the man who realizes Capone has not filed an income tax return for four years. The newly formed Untouchables begin as squeaky clean good guys; De Palma even shoots a whiskey raid at the Canadian border with Ness’ men on horseback, making a heroic charge at the bad guys to Morricone’s gallant score. They begin their charge as unwavering cowboys chasing after a villain in black; until, in the very same sequence, they become killers. The paper pusher Wallace unloads his shotgun on several gangsters, and then, when no one’s looking, celebrates with a mouthful of booze from a leaking barrel. Dangerously, they enjoy being heroes, not to mention the killing and drinking it affords them.

Opposite Capone stands Treasury Department agent Eliot Ness, who at first is naïve to the corruption of Chicago. After Capone’s men are tipped-off to Ness’ first raid, he resolves to recruit a squad of clean, incorruptible policemen. He seeks out Malone, an honest, but experienced beat cop, for guidance. De Palma shoots the scenes in which Ness and Malone assemble their Untouchables mindful of a similar sequence from John Sturges’ The Magnificent Seven (1960). He even instructed Ennio Morricone to evoke the composer’s own scores on films like Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) in the music for The Untouchables, resulting in an echoing harmonica that arouses a kind of Western atmosphere. Ness and Malone acquire George Stone (Andy Garcia), an Italian sharpshooter still working his way through the academy. They also bring along the nebbish federal accountant Oscar Wallace (Charles Martin Smith), the man who realizes Capone has not filed an income tax return for four years. The newly formed Untouchables begin as squeaky clean good guys; De Palma even shoots a whiskey raid at the Canadian border with Ness’ men on horseback, making a heroic charge at the bad guys to Morricone’s gallant score. They begin their charge as unwavering cowboys chasing after a villain in black; until, in the very same sequence, they become killers. The paper pusher Wallace unloads his shotgun on several gangsters, and then, when no one’s looking, celebrates with a mouthful of booze from a leaking barrel. Dangerously, they enjoy being heroes, not to mention the killing and drinking it affords them.

However, Ness soon realizes Capone will stop at nothing to keep liquor flowing in Chicago’s underground speakeasies and bootlegger bars. “What are you prepared to do?” Malone asks. “Everything within the law,” Ness replies. “And then what are you prepared to do?” Malone asks again. A dominant theme in The Untouchables remains Ness’ moral decline—his transformation from an idealistic young agent and family man into someone who must commit crimes in order to nab his man. He’s a straight-arrow among three other uniquely suited types: An Italian, Stone fights against his own people on a force made up of predominantly Irish and Polish men. (Interestingly, Garcia was originally brought in to read for the role of Capone’s right-hand assassin, Frank Nitti, but was drawn more to Stone.) A bookworm with glasses and pipe, Wallace feels invigorated by the job’s valor and gunplay. Malone is more complicated. He’s the kind of man who answers a midday knock at his door with a sawed-off double-barrel shotgun in hand. He knows the rotten core of Chicago, and he has long abstained from becoming involved, perhaps out of fear of dying or becoming corrupt, or perhaps because he knows he would enjoy it too much. To be sure, he seems to enjoy propping up a gangster’s corpse and pretending the man is still alive, if only to put a bullet through the corpse’s head to frighten a witness into becoming an informant. “You wanna know how to get Capone?” he asks Ness. “They pull a knife, you pull a gun. He sends one of yours to the hospital, you send one of his to the morgue. That’s the Chicago way.”

Before Ness can truly overcome a human beast of Capone’s caliber, though, he must shed his weaknesses, and then carefully walk the line between good and evil. From the outset, Capone’s masculinity defines him; he’s surrounded by tough men with guns, while other men in the press admire and laugh at his jokes. Never do we see a woman by his side. By contrast, Ness is surrounded by women: his wife Catherine (Patricia Clarkson) and their young daughter, to whom he gives delicate butterfly kisses. Butterflies symbolize Ness’ femininity. When the press mocks his initial failures, they call him “poor butterfly” and liken him to the suicidal wife in Puccini’s opera, Madame Butterfly—a character who waits up for her husband only to be humiliated. Ness is a man bound by his family. He endearingly remarks, “It’s nice to be married,” and smiles at the note his wife included with his lunch reading, “I’m very proud of you.” But Ness is too close to the wholesome family ideology he’s trying to preserve. Capone sees Ness’ weakness and uses his slimy hitman Frank Nitti (Billy Drago) to issue a veiled threat to Ness’ family. Ness knows he must send away his wife and daughter—a pointedly feminine and therefore vulnerable family in these very classicized terms—to focus his energies on Capone. Ness responds by delivering a categorical blow to Capone’s establishment on the Canadian border, unleashing the mobster’s usually controlled fury: “I want you to get this fuck where he breathes! I want you to find this nancy-boy Eliot Ness, I want him dead! I want his family dead! I want his house burned to the ground! I wanna go there in the middle of the night and I wanna piss on his ashes!”

Before Ness can truly overcome a human beast of Capone’s caliber, though, he must shed his weaknesses, and then carefully walk the line between good and evil. From the outset, Capone’s masculinity defines him; he’s surrounded by tough men with guns, while other men in the press admire and laugh at his jokes. Never do we see a woman by his side. By contrast, Ness is surrounded by women: his wife Catherine (Patricia Clarkson) and their young daughter, to whom he gives delicate butterfly kisses. Butterflies symbolize Ness’ femininity. When the press mocks his initial failures, they call him “poor butterfly” and liken him to the suicidal wife in Puccini’s opera, Madame Butterfly—a character who waits up for her husband only to be humiliated. Ness is a man bound by his family. He endearingly remarks, “It’s nice to be married,” and smiles at the note his wife included with his lunch reading, “I’m very proud of you.” But Ness is too close to the wholesome family ideology he’s trying to preserve. Capone sees Ness’ weakness and uses his slimy hitman Frank Nitti (Billy Drago) to issue a veiled threat to Ness’ family. Ness knows he must send away his wife and daughter—a pointedly feminine and therefore vulnerable family in these very classicized terms—to focus his energies on Capone. Ness responds by delivering a categorical blow to Capone’s establishment on the Canadian border, unleashing the mobster’s usually controlled fury: “I want you to get this fuck where he breathes! I want you to find this nancy-boy Eliot Ness, I want him dead! I want his family dead! I want his house burned to the ground! I wanna go there in the middle of the night and I wanna piss on his ashes!”

The Untouchables occupies very traditional, even outdated views on masculine heroes and feminine weakness, in part because the film seeks to tell a classical kind of story. The film remains more complicated around Ness’ questions of his own moral certainty. As he allows himself to become tougher and more masculine, Ness worries about becoming an evil man. This remains the key difference between Ness and Capone, since the latter embraces crime and unflinching cruelty without hesitation, such as sending Nitti to kill the prosecution’s key witness and slaughter Wallace; in the elevator where he kills them, Nitti writes “touchable” on the wall in Wallace’s blood. The next evening, Capone sends his men to shoot down Malone in his home. The sequence is shot from a point-of-view angle straight out of De Palma’s own Blow Out, following a mob killer peering through Malone’s windows and sneaking through his house until, finally, Malone rushes his would-be assassin out the back door—only to be gunned down by Nitti, who waits to strike in the distance. For Ness, a family man of unshakable moral values, Capone’s savage violence finally brings him to the edge.

After all, Ness begins as an incomparable straight man. Because of the Volstead Act, and only because of it, he resists drinking and demands that his men avoid alcohol as well. When he finally grows frustrated with his lack of progress and seeks guidance, Malone takes him into a church of all places. Connery suggested the location to De Palma, believing Malone’s logic of “two eyes for an eye” served as a kind of righteous morality. De Palma once again shoots from a low angle, capturing the church’s elaborately vaulted ceiling, as though God was looking down on them, watching Malone make his argument with divine approval. Later, righteousness is barely enough. Ness breaks down, “I have foresworn myself. I have broken every law I have sworn to uphold, I have become what I beheld and I am content that I have done right.” Finally, Ness’ personal victory comes twofold: Capone’s attempt to bribe his jury results in the judge swapping them with the jury in the next courtroom, presumably leading to Capone’s eventual conviction of tax evasion in court. But no court is good enough for someone like Nitti in Ness’ present state. A rooftop chase scene sends Ness after Nitti, and the villain, curiously dressed in all white instead of all black, taunts our hero. “Arrest me!” he shouts, knowing Capone can get him out of it. “You tell Capone that I’ll see him in hell,” says Ness, and then rushes Nitti over the edge of the building where he falls to his death. Ness’ remark during his act of vengeance suggests that he knows his crimes will land him in hell, right alongside Capone.

After all, Ness begins as an incomparable straight man. Because of the Volstead Act, and only because of it, he resists drinking and demands that his men avoid alcohol as well. When he finally grows frustrated with his lack of progress and seeks guidance, Malone takes him into a church of all places. Connery suggested the location to De Palma, believing Malone’s logic of “two eyes for an eye” served as a kind of righteous morality. De Palma once again shoots from a low angle, capturing the church’s elaborately vaulted ceiling, as though God was looking down on them, watching Malone make his argument with divine approval. Later, righteousness is barely enough. Ness breaks down, “I have foresworn myself. I have broken every law I have sworn to uphold, I have become what I beheld and I am content that I have done right.” Finally, Ness’ personal victory comes twofold: Capone’s attempt to bribe his jury results in the judge swapping them with the jury in the next courtroom, presumably leading to Capone’s eventual conviction of tax evasion in court. But no court is good enough for someone like Nitti in Ness’ present state. A rooftop chase scene sends Ness after Nitti, and the villain, curiously dressed in all white instead of all black, taunts our hero. “Arrest me!” he shouts, knowing Capone can get him out of it. “You tell Capone that I’ll see him in hell,” says Ness, and then rushes Nitti over the edge of the building where he falls to his death. Ness’ remark during his act of vengeance suggests that he knows his crimes will land him in hell, right alongside Capone.

De Palma conjures romantic visions of Westerns and archetypal conflicts between good and evil throughout cinema in The Untouchables, informing the film’s complex moral themes by contrasting them against our cinematic memory and nostalgia for similar stories, which have been brought to aesthetic life in the film’s production design, costumes, and music. Perhaps the most famous moment in the film takes place on marble stairs in a train station, where Ness and Stone wait to detain Capone’s bookkeeper, a critical witness. The scene crosscuts between Ness anxiously looking at the station clock, a woman who struggles to pull her baby’s carriage up the stairs to make her train, and several of Capone’s men. Although this rousing scene originally involved an elaborate helicopter chase, the production ran out of money, requiring De Palma to design the near-wordless sequence on the fly. His masterful orchestration of suspense drops into slow-motion as a shootout begins; the mother’s carriage begins descending the stairs; Ness races after the baby, and all the while exchanges rounds with Capone’s men. The sequence recalls an iconic moment from Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925), and similarly staged train station sequences from De Palma’s oft-borrowed influence, Alfred Hitchcock. But the precise and calculating, yet utterly breathless scene is pure De Palma, particularly in the way he uses established imagery to place his audience in an unconscious state of mind linked to the past, if only to embark on an altogether new perspective.

Although Brian De Palma took The Untouchables as a studio job to service his smaller, more involved passion projects, the outcome feels personal and uniquely carved from the director’s point-of-view. Where journeyman filmmakers disappear into their chosen production, De Palma remains such a singular force that even his studio jobs feel like the work of an auteur, ingrained with similar themes and obsessions as his original independent releases like Obsession, Blow Out, Dressed to Kill, Body Double, Raising Cain, and Femme Fatale. To be sure, De Palma’s more commercial-minded output (Carrie, Mission: Impossible, Carlito’s Way, Snake Eyes, etc.) nonetheless feels shaped by a master filmmaker controlling his craft in a way few other directors are capable. The Untouchables stands above his other studio pictures as a timeless, thought-provoking work of visual signifiers and bold thematic turns. Mamet’s sharp and often beautifully written script guides Ness’ journey into the heart of moral darkness, revealing that the Untouchables are, in fact, morally and physically, touchable. De Palma’s splendidly designed film at once embraces nostalgia and traditional hero roles, but also asks that his audience ponders the faulty nature of such classic, romanticized ideas by saturating them with grave implications.

Although Brian De Palma took The Untouchables as a studio job to service his smaller, more involved passion projects, the outcome feels personal and uniquely carved from the director’s point-of-view. Where journeyman filmmakers disappear into their chosen production, De Palma remains such a singular force that even his studio jobs feel like the work of an auteur, ingrained with similar themes and obsessions as his original independent releases like Obsession, Blow Out, Dressed to Kill, Body Double, Raising Cain, and Femme Fatale. To be sure, De Palma’s more commercial-minded output (Carrie, Mission: Impossible, Carlito’s Way, Snake Eyes, etc.) nonetheless feels shaped by a master filmmaker controlling his craft in a way few other directors are capable. The Untouchables stands above his other studio pictures as a timeless, thought-provoking work of visual signifiers and bold thematic turns. Mamet’s sharp and often beautifully written script guides Ness’ journey into the heart of moral darkness, revealing that the Untouchables are, in fact, morally and physically, touchable. De Palma’s splendidly designed film at once embraces nostalgia and traditional hero roles, but also asks that his audience ponders the faulty nature of such classic, romanticized ideas by saturating them with grave implications.

Bibliography:

Keesey, Douglas. Brian De Palma’s Split-Screen. Mississippi: The University Press of Mississippi, 2015.

Peretz, Eyal. Becoming Visionary: Brian De Palma’s Cinematic Education of the Senses. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2008.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review