The Definitives

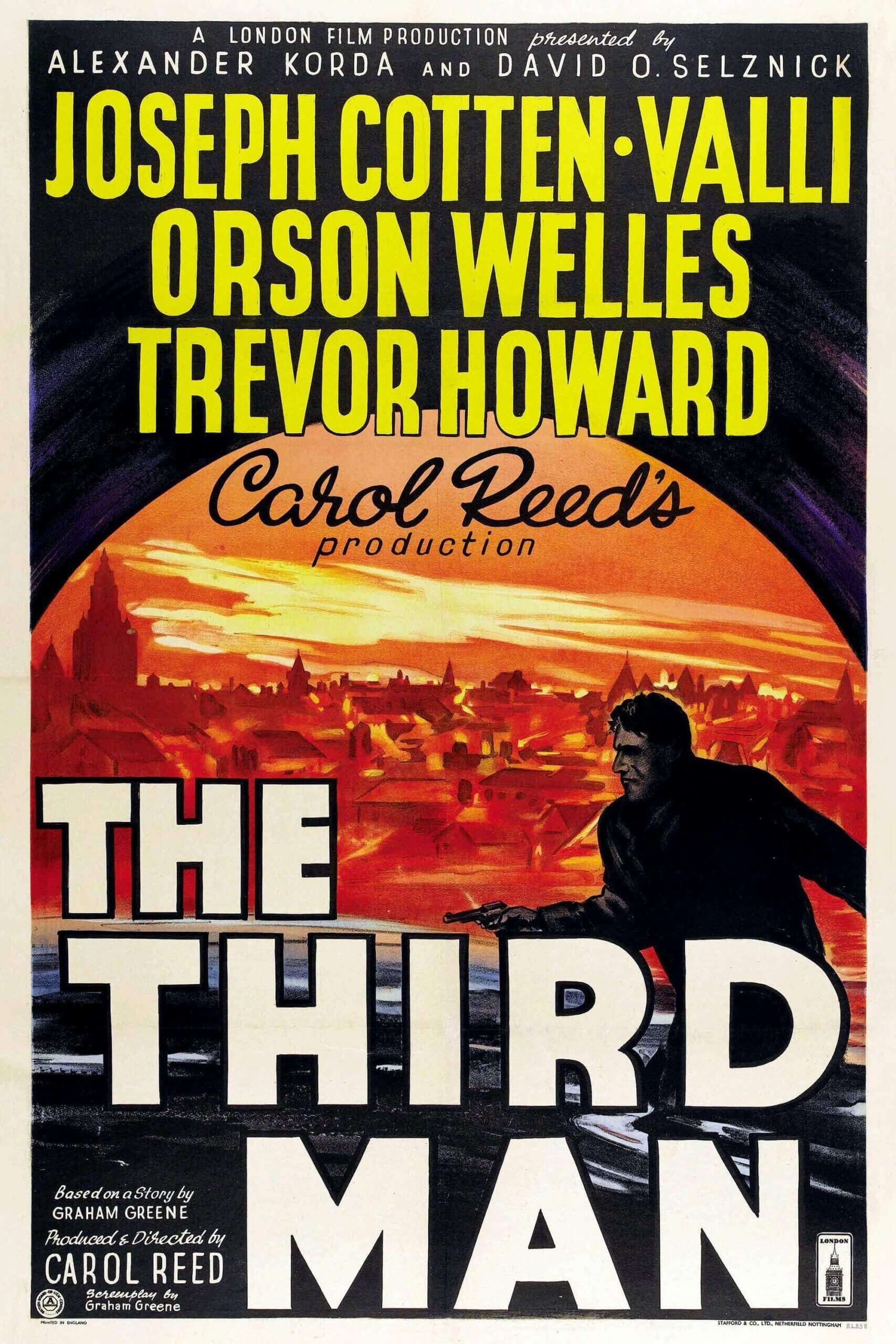

The Third Man (1949)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

An ominous figure stands enveloped in a shadowy doorway, wrapped in a blanket of darkness, almost perfectly hidden save for its legs and feet. The wet street glistens, defining every cobblestone, while the surrounding Viennese architecture juts out. The geometry of light around the scene dances in dark harmony with the night. Although he cannot see the figure’s face, Holly Martins knows someone watches him from the shadows. And Martins might be frightened by the anonymous gaze of this mysterious, faceless person, except he sees a kitten cleaning itself between the figure’s legs. Whatever intimidating presence this figure might have, it’s somehow silly next to a kitten. Martins shouts, “Come out, come out, whoever you arrrre!” On the opposite streetside, a woman opens her window to scold Martins for his mid-night shouting. She flicks a light on, and all at once, it reveals the figure’s face. This is Harry Lime, whom Martins believed to be dead, played by Orson Welles. This is also the most memorable entrance in movie history. As the camera zooms in and Lime smiles his wry, knowing smile, he does so with the same “cheerful rascality” that Graham Greene described in his script and Welles himself maintained in life.

The Third Man follows an idealistic American writer of Westerns as he arrives in the corrupted, disparaged city of post-WWII Vienna, Austria, divvied into four sections: French, Russian, British, and American. Holly Martins (Joseph Cotten) is an innocent, in some ways a clod, as he blindly follows a mystery, however dangerous, until its ultimate conclusion—all for a girl about whom he knows nothing. A writer of low-brow dime novels, Martins hopes to meet his friend Lime for a job offer. But as Martins learns, Lime is now dead. A car struck him, and several witnesses attest to the accident. Martins investigates with no money to return home, weaving between black market hoods and nosy official Major Calloway (Trevor Howard). Lime’s girl, Anna Schmidt (Alida Valli), follows Martins’ progress but rejects his advances. How could anyone compare with Harry Lime? With enough inconsistencies in the various eyewitness accounts to believe his friend Lime was murdered, Martins’ investigation makes him realize that Lime is alive and staged his own death. And this brings us up to date where, in the shadowy doorway, Lime stands smiling. Built-up for over an hour, Harry Lime’s entrance in The Third Man is more about showmanship and about being the star than about Martins having finally solved the mystery of Who Killed Harry Lime?—the answer for which, of course, is no one. The role is a “star vehicle,” as Welles himself described it in an interview with Peter Bogdanovich, saying, “What counts is how much the other characters talk about you. Such a star vehicle really is a vehicle. All you have to do is ride.”

Welles rode the part of Harry Lime right over the film’s star Joseph Cotten, all but running over director Carol Reed and writer Graham Greene in the process. Reed directed The Third Man in the autumn of 1948 with British filmmaker Sir Alexander Korda (Rembrandt, 1936) and American legend David O. Selznick (Gone with the Wind, 1939) producing. Greene wrote the story into a treatment about the length of a short novel, basing it on a concept both he and Reed developed, and then he adapted it into screenplay form. Greene had collaborated with Reed on the director’s previous film, The Fallen Idol (1948), so their partnership was sound. Faithfully adapting Greene’s work was a priority for Reed; there was an impressive absence of creative jealousy between the two. Reed was a collaborator, or at least gave the illusion of being a collaborator. His production worked in three shifts, and he attempted to direct them all, determined to have complete control over almost every detail. He would refuse sleep and film in shifts for daylight scenes, sewer sequences, and on the street at night, barely needing a wink thanks to Benzedrine. But with time, all the hard work of both the film’s writer and director would be overshadowed next to Welles’ presence.

Welles rode the part of Harry Lime right over the film’s star Joseph Cotten, all but running over director Carol Reed and writer Graham Greene in the process. Reed directed The Third Man in the autumn of 1948 with British filmmaker Sir Alexander Korda (Rembrandt, 1936) and American legend David O. Selznick (Gone with the Wind, 1939) producing. Greene wrote the story into a treatment about the length of a short novel, basing it on a concept both he and Reed developed, and then he adapted it into screenplay form. Greene had collaborated with Reed on the director’s previous film, The Fallen Idol (1948), so their partnership was sound. Faithfully adapting Greene’s work was a priority for Reed; there was an impressive absence of creative jealousy between the two. Reed was a collaborator, or at least gave the illusion of being a collaborator. His production worked in three shifts, and he attempted to direct them all, determined to have complete control over almost every detail. He would refuse sleep and film in shifts for daylight scenes, sewer sequences, and on the street at night, barely needing a wink thanks to Benzedrine. But with time, all the hard work of both the film’s writer and director would be overshadowed next to Welles’ presence.

Some might say that Welles’ reputation preceded him. By 1948, Welles had already directed Citizen Kane (1941) and The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), two of what were considered the best movies ever made—something both cineastes and audiences in 1948 did not yet realize. Even so, Welles’ ambitious projects often flopped, and many never moved beyond the planning stages. He was perhaps too hopeful a filmmaker, which in Hollywood terminology means he was naïve. By the time pre-production on The Third Man began, Welles had just finished filming an adaptation of Shakespeare’s Macbeth for Republic. Misunderstood in the United States, Welles escaped the unappreciative vultures of Hollywood in the summer of 1947 by moving to Europe. He spent most of his time in Italy for Macbeth’s post-production, ostensibly hiding for several reasons. Welles biographer David Thompson suggests that Welles hoped to evade an approaching, reportedly justified, IRS audit. Or perhaps he fled to escape the House Committee on Un-American Activities and their questions, as Welles knew the FBI’s file on him alluded to his alleged, and wholly unfounded, communist ties.

Welles hopped from hotel to hotel around Europe, free from studio contracts and other such Hollywood constraints. He enjoyed his Havana cigars and rich food, spending money, and telling stories. His life in Europe afforded him a grand time, albeit a costly one. Friends and women were expensive, but being desperate for congeniality, Welles spent the money and racked up debt. All these joys were simply a distraction from his most recent commercial failure, Macbeth, which took months to edit, a process troubled by the “unintelligible” Scottish accents, insisted upon by Welles for accuracy’s sake. Before filming his following picture, The Third Man, Welles signed a three-picture deal with Alexander Korda in 1946. The contract committed Welles to three films in the capacity of writer, director, or producer for a hefty sum upfront and a small cut of box office receipts. Unfortunately, most of the projects Welles sought to fulfill the contract (among others, adaptations of Henry IV and War and Peace) never solidified—most notably a production of Cyrano de Bergerac that Welles had rewritten from Ben Hecht and Harry d’Abbadie d’Arrast’s script.

Welles hopped from hotel to hotel around Europe, free from studio contracts and other such Hollywood constraints. He enjoyed his Havana cigars and rich food, spending money, and telling stories. His life in Europe afforded him a grand time, albeit a costly one. Friends and women were expensive, but being desperate for congeniality, Welles spent the money and racked up debt. All these joys were simply a distraction from his most recent commercial failure, Macbeth, which took months to edit, a process troubled by the “unintelligible” Scottish accents, insisted upon by Welles for accuracy’s sake. Before filming his following picture, The Third Man, Welles signed a three-picture deal with Alexander Korda in 1946. The contract committed Welles to three films in the capacity of writer, director, or producer for a hefty sum upfront and a small cut of box office receipts. Unfortunately, most of the projects Welles sought to fulfill the contract (among others, adaptations of Henry IV and War and Peace) never solidified—most notably a production of Cyrano de Bergerac that Welles had rewritten from Ben Hecht and Harry d’Abbadie d’Arrast’s script.

Working with Korda, an independent producer as influential as Selznick himself, Welles was suddenly a hot commodity as an artist. Not so for Selznick, who saw actors as contracted machinery, a truth Wells had seen first-hand (Selznick talked Welles out of $25,000 for narrating Duel in the Sun so the producer could avoid some taxes; instead, he suggested a pricey Christmas present. Welles waited around until that Christmas when he received Selznick’s gift: dueling pistols worth $125). Many artists to work under Selznick (Alfred Hitchcock, King Vidor, etc.) would find that the producer demanded absolute control, much to the chagrin of otherwise controlling directors. Korda, at least, had a collaborative sense; he lacked the often piggish childishness of Selznick. Korda was in charge of The Third Man’s production in Europe, while Selznick spent most of his time in the states. Carol Reed, however, made most of the production’s creative decisions, and Korda left him to it.

Joseph Cotten was not Reed’s first choice for Martins; the director preferred Cary Grant or even Jimmy Stewart. But Grant and Stewart wanted too much money. Luckily so, since neither could have given Martins the necessary dumbfounded ignorance toward Vienna the role requires—they would have been too charming (not that Cotten was incapable of charisma; rather, he could switch it on and off). Cotten sticks out like a sore thumb and pokes his nose where it doesn’t belong, his head ever inquisitively cocked to the side. His intentional downplayed onscreen charm, which is always present in Grant and Stewart in their films, proves selfless and fully allows Welles to take over eventually. We believe in Cotten’s blind obliviousness to everything un-American. Martins is an author of Wild West stories. He seems stuck in a romantic Western storyline populated by heroes and villains, completely unable to see the gray areas forming between these extremes. But The Third Man does not unfold in America, and Greene’s vision of postwar Vienna is not the Old West. The entire picture, as we discover, takes place in the gray morality of postwar Europe.

Joseph Cotten was not Reed’s first choice for Martins; the director preferred Cary Grant or even Jimmy Stewart. But Grant and Stewart wanted too much money. Luckily so, since neither could have given Martins the necessary dumbfounded ignorance toward Vienna the role requires—they would have been too charming (not that Cotten was incapable of charisma; rather, he could switch it on and off). Cotten sticks out like a sore thumb and pokes his nose where it doesn’t belong, his head ever inquisitively cocked to the side. His intentional downplayed onscreen charm, which is always present in Grant and Stewart in their films, proves selfless and fully allows Welles to take over eventually. We believe in Cotten’s blind obliviousness to everything un-American. Martins is an author of Wild West stories. He seems stuck in a romantic Western storyline populated by heroes and villains, completely unable to see the gray areas forming between these extremes. But The Third Man does not unfold in America, and Greene’s vision of postwar Vienna is not the Old West. The entire picture, as we discover, takes place in the gray morality of postwar Europe.

Though Selznick wanted Noël Coward for Harry Lime, Reed and Korda agreed upon Orson Welles. But like Lime, Welles was elusive. Rumors placed Welles in various cities around Europe. Getting him to sign for The Third Man involved, first, finding Welles. The star was box office poison; he had directed only one profitable film, The Stranger, in 1946. By contrast, Reed was acclaimed not only for The Fallen Idol but for Odd Man Out (1947), both minor commercial and major critical successes. As a result, Welles was reportedly nervous about working with Reed and was possibly avoiding him. Getting him to sign was just a matter of talking Welles into the part and signing the contract, which required getting him drunk. Compelling Welles to actually show up and honor the contract was another story. Reed began filming in Vienna and incorporated a bounty of rich aesthetics to fill every scene with generous detail in the interim. He placed sculptures in the background for dramatic effect, such as the fountain where Holly Martins stops after chasing Harry Lime down the alley. Every extra was hand-picked by assistant director Guy Hamilton for their unique, distinctive look; he found extras at a nearby soup kitchen or took them right off the street. Such details reside just under the surface, alluding to Reed’s vast storytelling craftsmanship. He did not believe his films were art, nor did he believe in the auteur theory. In Reed’s mind, a director was not a personality but the accumulation of talent involved in a production.

Still, Reed no doubt began to feel like Holly Martins. While Martins was asked to come to Vienna for a job only to be stuck there when he finds his friend is dead, Reed was in the middle of making a movie and suddenly could not find his Harry Lime. Welles became the proverbial Lime, with Reed’s production crew scouring all of Europe to find their Third Man. By the time Reed was ready to shoot Welles’ scenes, the actor was still nowhere to be found. Welles avoided the production, purportedly on purpose, causing Vincent Korda (Alexander’s brother) and his son Michael to follow a trail of receipts and rumors to find their man. Still, they were always two steps behind Welles. From Rome’s Grand Hotel to Florence, and then to the Venice Film Festival where Macbeth was to be shown (only later to be barred), the two Welles hunters caught wind of their prey in Naples, so off they went, finding Welles had already left for Capri. One has to assume Welles had an idea he was being followed and certainly enjoyed the adventure of the chase. Imagine him laughing heartily, puffing on his Havana at the irony of their pursuit, how it paralleled the same script they were hoping to film. Welles finally gave the father-son Korda team a rest; they found him after he stopped in Nice’s Hotel Ruhl.

Still, Reed no doubt began to feel like Holly Martins. While Martins was asked to come to Vienna for a job only to be stuck there when he finds his friend is dead, Reed was in the middle of making a movie and suddenly could not find his Harry Lime. Welles became the proverbial Lime, with Reed’s production crew scouring all of Europe to find their Third Man. By the time Reed was ready to shoot Welles’ scenes, the actor was still nowhere to be found. Welles avoided the production, purportedly on purpose, causing Vincent Korda (Alexander’s brother) and his son Michael to follow a trail of receipts and rumors to find their man. Still, they were always two steps behind Welles. From Rome’s Grand Hotel to Florence, and then to the Venice Film Festival where Macbeth was to be shown (only later to be barred), the two Welles hunters caught wind of their prey in Naples, so off they went, finding Welles had already left for Capri. One has to assume Welles had an idea he was being followed and certainly enjoyed the adventure of the chase. Imagine him laughing heartily, puffing on his Havana at the irony of their pursuit, how it paralleled the same script they were hoping to film. Welles finally gave the father-son Korda team a rest; they found him after he stopped in Nice’s Hotel Ruhl.

Welles’ scenes were filmed first in Vienna and then in England and totaled two weeks of shooting. Aside from a few shots in Vienna, there was a mere five days shot in Shepperton, Surrey, in England—three days filming dialogue at the Great Wheel and two days on the sewer set. Since Welles refused to shoot in Viennese sewers, having complained that the damp environment and unsanitary conditions were too much, the cleaner sewers set in Shepperton accommodated the actor. Viennese sewers or not, Reed discovered the intrinsic pleasure of watching Welles take a bath in sewer water. When out of the director’s chair and not in absolute control of production, Welles was famous for his flaky, eccentric behavior. He arrived on set tardy or left in the middle of shooting, which is why Assistant Director Guy Hamilton filled in for shadow-only shots of Harry Lime. Welles’ professional respect for Reed did not stand in the way of lengthening his time on set to increase his fee, either. Money was money, and throughout his career, Welles took acting work to help finance his directorial projects. The Third Man’s earnings, combined with paydays from Prince of Foxes (1949) and The Black Rose (1950), would eventually back Welles’ 1952 version of Shakespeare’s Othello, for which he earned the Grand Prix at the 1952 Cannes Film Festival.

Welles purportedly interrupted Reed’s directorial schema on the set, offering suggestions for how certain scenes might be better filmed. Reed remained impressively professional yet inflexible and did so without insulting his star. The director agreed to shoot Welles’ vision of a given shot, but only after shooting his own version repeatedly until Welles was too tired to try out his ideas. Reed always prevailed, according to crew reports. In the editing room, Reed also butted heads with the control-happy Selznick over points of character, mood, and American exceptionalism (even though after seeing a rough cut, Selznick called the film “superb”). Selznick had little to do with The Third Man’s day-to-day production but sent Reed constant wires suggesting incongruous ideas for the film, which Korda and Reed would disregard. Selznick’s famous addiction to Benzedrine, likely the cause of his chronic diarrhea and sleepless nights, meant more work could be accomplished in his never-ending stream of waking hours. This also meant his production notes to Korda and Reed were sometimes erratic. The producer became infamous for such correspondence, as his memos popped up in the production notes of several Selznick pictures. It was as if the producer had no understanding whatsoever of the film’s intent. For example, Selznick wanted star Alida Valli (whom he had discovered) to look beautiful and appear in extravagant costumes fitting for a Hollywood star. Her character is a poor black marketeer, unable to afford expensive clothing or makeup. Reed argued against Selznick’s suggestion, eventually winning his debate so that Valli’s garb is humble, therefore realistic.

Welles purportedly interrupted Reed’s directorial schema on the set, offering suggestions for how certain scenes might be better filmed. Reed remained impressively professional yet inflexible and did so without insulting his star. The director agreed to shoot Welles’ vision of a given shot, but only after shooting his own version repeatedly until Welles was too tired to try out his ideas. Reed always prevailed, according to crew reports. In the editing room, Reed also butted heads with the control-happy Selznick over points of character, mood, and American exceptionalism (even though after seeing a rough cut, Selznick called the film “superb”). Selznick had little to do with The Third Man’s day-to-day production but sent Reed constant wires suggesting incongruous ideas for the film, which Korda and Reed would disregard. Selznick’s famous addiction to Benzedrine, likely the cause of his chronic diarrhea and sleepless nights, meant more work could be accomplished in his never-ending stream of waking hours. This also meant his production notes to Korda and Reed were sometimes erratic. The producer became infamous for such correspondence, as his memos popped up in the production notes of several Selznick pictures. It was as if the producer had no understanding whatsoever of the film’s intent. For example, Selznick wanted star Alida Valli (whom he had discovered) to look beautiful and appear in extravagant costumes fitting for a Hollywood star. Her character is a poor black marketeer, unable to afford expensive clothing or makeup. Reed argued against Selznick’s suggestion, eventually winning his debate so that Valli’s garb is humble, therefore realistic.

Filming had wrapped, and Selznick was scheduled to view a rough cut on July 26, 1949, but an “accident” occurred. A fire destroyed six reels, requiring Reed to re-edit from another rough cut the director used when working with musician Anton Karas to record the film’s iconic zither music. Selznick would not see a finished copy of The Third Man for another month, just in time to make their Cannes Film Festival date and win Grand Prix. Before the film’s wide release, Selznick demanded an “American Cut” with the film’s allusion to corrupt American police removed and the film’s opening monologue altered so that Holly Martins comes off as an American hero. However, in Reed’s cut, an anonymous racketeer voiced by Reed himself opens the film, feeding the idea that we’re being told The Third Man’s events as part of an inconsequential tale, communicated like a back alley yarn. Reed’s version contains mystery and walks us through the gates into Harry Lime’s world so that our “hero” Holly Martins takes an outsider position. Selznick’s cut features Cotten giving a heralding substantiation to the American everyman hero, eliminating any mystery or ambiguity, and certainly not questioning Martins’ placement in Vienna. Selznick’s version outlined another of Hollywood’s then-popular idealized American heroes, conquering foreign lands the way only an American could.

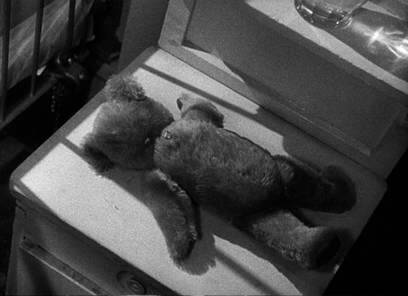

Selznick also recut several scenes that removed Reed’s pure artistry from the film, even its logical continuity—changes exclusive to his now-shunned, universally unavailable version. For example, he cut the near-naked stripper per demands by the Catholic Legion of Decency. In Reed’s version, her appearance describes the seedy underworld Martins discovers while investigating his friend’s death. This is Harry Lime’s world—another planet, specifically not America. Among other changes, Selznick shows a child in the hospital near the end, visually demonstrating the result of Harry Lime’s penicillin tampering; but this turns Harry Lime into an ugly monster instead of a charming one. Seeing what he has done, we, therefore, see his crimes as unforgivable. Reed’s cut shows us only Cotten’s face reacting to the dying child, and the child’s teddy bear discarded as its owner no longer needs it. Reed’s version allows the audience’s emotional reaction to occur naturally, rather than blatantly telling us what to feel—we see what to feel by reading Cotten’s face, and through this, we better relate to the protagonist. Hatred for Harry Lime on the part of the audience is impossible, making the final “showdown” less about carrying out a death sentence and more about a friend’s betrayal.

Selznick also recut several scenes that removed Reed’s pure artistry from the film, even its logical continuity—changes exclusive to his now-shunned, universally unavailable version. For example, he cut the near-naked stripper per demands by the Catholic Legion of Decency. In Reed’s version, her appearance describes the seedy underworld Martins discovers while investigating his friend’s death. This is Harry Lime’s world—another planet, specifically not America. Among other changes, Selznick shows a child in the hospital near the end, visually demonstrating the result of Harry Lime’s penicillin tampering; but this turns Harry Lime into an ugly monster instead of a charming one. Seeing what he has done, we, therefore, see his crimes as unforgivable. Reed’s cut shows us only Cotten’s face reacting to the dying child, and the child’s teddy bear discarded as its owner no longer needs it. Reed’s version allows the audience’s emotional reaction to occur naturally, rather than blatantly telling us what to feel—we see what to feel by reading Cotten’s face, and through this, we better relate to the protagonist. Hatred for Harry Lime on the part of the audience is impossible, making the final “showdown” less about carrying out a death sentence and more about a friend’s betrayal.

Selznick meant well, but his meddling caused many of Hollywood’s most troublesome productions. In any case, his pictures were successes; Korda’s were generally not, however artistically winning they might be. And perhaps that is how Selznick justified his creative alterations. Selznick had already Americanized one British director, Alfred Hitchcock, and made him a massive triumph in the states. He had the same intention for Reed. The producer even purchased U.S. distribution rights to Reed’s The Fallen Idol and, along with The Third Man, hoping to manufacture another Hitchcock. Meanwhile, Reed fought to make his cut as he believed it should be. Indeed, his most significant victory came after his battle against studio heads over Anton Karas’ zither twang, as opposed to an orchestrated and dramatic film score. The director heard the zither player on their first day in Vienna at a welcome party hosted by Austrian filmmaker Karl Hartl. Like an obsessed child, Reed sat in front of Karas, listening to the winding tune which remained in his head for days. Karas later received an invitation to play the music privately for Reed; when Karas arrived, Reed proposed turning the tune into a film score. Karas agreed, and a sound crew recorded what would be known as “The Third Man Theme.”

After editing his footage and adding Karas’ music, Reed sent his cut to studio heads, only to receive a telegram back saying the film is excellent, “but please take off the banjo.” Reed opted to leave it on. After the film’s hugely successful London release in September of 1949, Decca Records put out an album featuring “The Harry Lime Theme” that sold one-half million copies by the following November. In the U.S., The Third Man opened to rave reviews and audience reception, so London Records released the tune in various editions, selling around 40 million copies over the subsequent years. It was the third most popular record in America in the 1950s, spending eleven weeks at number one on Billboard’s chart of top-selling records. The music’s presence has character, so much so that it is often called “The Fourth Man.” No matter the scene, when Karas’ pleasant, blithely joyous zither is present, there’s an irony also at work; tragedy and humor labor simultaneously, so that every scene is both light yet pointedly noirish.

After editing his footage and adding Karas’ music, Reed sent his cut to studio heads, only to receive a telegram back saying the film is excellent, “but please take off the banjo.” Reed opted to leave it on. After the film’s hugely successful London release in September of 1949, Decca Records put out an album featuring “The Harry Lime Theme” that sold one-half million copies by the following November. In the U.S., The Third Man opened to rave reviews and audience reception, so London Records released the tune in various editions, selling around 40 million copies over the subsequent years. It was the third most popular record in America in the 1950s, spending eleven weeks at number one on Billboard’s chart of top-selling records. The music’s presence has character, so much so that it is often called “The Fourth Man.” No matter the scene, when Karas’ pleasant, blithely joyous zither is present, there’s an irony also at work; tragedy and humor labor simultaneously, so that every scene is both light yet pointedly noirish.

Everyone from general audiences to art critics like André Bazin loved The Third Man upon its release. Only the Viennese criticized the picture, arguing it depicted Vienna as “a dangerous place.” They also accused writer Graham Greene of purporting “trash” and said Reed used Vienna as a scapegoat for criminality. Among the reviews, Reed seldom received due credit for his picture. Most saw The Third Man as Reed aping Welles’ direction on Citizen Kane or his twisty noir The Lady from Shanghai (1947). In interviews, Welles perpetuated these notions and attributed himself to writing virtually the entire Harry Lime role—making what historians have called “extravagant claims” with “false modesty.” Many of the supposed Wellsian inspirations are now unverifiable and often disputed. For example, the idea that Welles suggested Lime’s fingers reaching desperately through the grille upon his death, even though they were Reed’s fingers filmed. True or not, Reed’s brilliance is unduly attributed to Welles’ brilliance as if Reed was somehow so taken with Welles’ presence on set that the director could not help but direct his entire film in a Wellesian style. Reed, never the braggart, refused to debunk Welles’ big-fish claims to creative influence publicly. The director even embraced the idea that Orson Welles was The Orson Welles from Hollywood lore—that Welles was The Artist’s Hero who directs every one of his scenes and writes all of his dialogue, even when starring in someone else’s picture.

This is, of course, not true and entirely absurd. Welles’ only piece of creative influence to show up onscreen in The Third Man was his famous “cuckoo clock” speech, which Welles wrote himself and sprung on the director on set. Spoken with Welles’ casual half-smile affinity for quickly conveyed, longwinded ideas, his brief monologue would go down as one of cinema’s greatest lines. After an illuminating Ferris wheel ride, Lime justifies his diluting of penicillin for black market profits, his killing of children for money, to his friend Martins. The conversation closes when the ride ends; Lime turns to his friend and says: “In Italy, for thirty years under the Borgias, they had warfare, terror, murder, bloodshed—but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and the Renaissance. In Switzerland, they had brotherly love, five hundred years of democracy and peace, and what did that produce? The Cuckoo clock. So Long Holly.” Some say that the speech was stolen from, but was likely just influenced by, James McNeill Whistler’s 1885 lecture on Art existing without the benefit of war and peace: “Art is,” Whistler would say. After the film’s release, Welles received a note that the Swiss never made cuckoo clocks—that they originated in Black Forest (Schwarzwald, Germany). It doesn’t really matter if the fact is false; Welles is not about facts, nor is Lime, but rather about personal truth.

This is, of course, not true and entirely absurd. Welles’ only piece of creative influence to show up onscreen in The Third Man was his famous “cuckoo clock” speech, which Welles wrote himself and sprung on the director on set. Spoken with Welles’ casual half-smile affinity for quickly conveyed, longwinded ideas, his brief monologue would go down as one of cinema’s greatest lines. After an illuminating Ferris wheel ride, Lime justifies his diluting of penicillin for black market profits, his killing of children for money, to his friend Martins. The conversation closes when the ride ends; Lime turns to his friend and says: “In Italy, for thirty years under the Borgias, they had warfare, terror, murder, bloodshed—but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and the Renaissance. In Switzerland, they had brotherly love, five hundred years of democracy and peace, and what did that produce? The Cuckoo clock. So Long Holly.” Some say that the speech was stolen from, but was likely just influenced by, James McNeill Whistler’s 1885 lecture on Art existing without the benefit of war and peace: “Art is,” Whistler would say. After the film’s release, Welles received a note that the Swiss never made cuckoo clocks—that they originated in Black Forest (Schwarzwald, Germany). It doesn’t really matter if the fact is false; Welles is not about facts, nor is Lime, but rather about personal truth.

Since Harry Lime dies at the end of The Third Man, shot dead by Martins after a thrilling chase through Vienna sewers, a radio program about Lime seems a far-fetched idea. But in 1951, Orson Welles banked on the film’s popularity, predominantly the public’s surprising love for his character Harry Lime, to spawn 52 episodes of “The Lives of Harry Lime.” Told in flashback, apparently from Limbo, tales of crime and intrigue are spoken from Lime’s perspective. The show mutated Lime from a selfish child-murdering black marketeer into a morally ambiguous yet leaning-toward-good-guy-type hero. In some episodes, he bought and sold heroin; in others, he rescued damsels in distress. On April 11th, 1952, an episode of “The Lives of Harry Lime” entitled “Man of Mystery” featured a character named Gregory Arkadin. Three years later, Welles would personify Arkadin in his famously raped-yet-brilliant film Mr. Arkadin. However, before the film, Welles wrote the novel Mr. Arkadin, which was the film’s inspiration (then again, his authorship of the novel has been debunked and reconfirmed several times, so perhaps it should be said that Welles allegedly wrote Mr. Arkadin). The similarities between The Third Man and Mr. Arkadin are undeniable: both involve one man scouring European black market crime circles to uncover the truth about another; both feature the death of their title character, the nature of whom the film’s respective hero does not understand. In Mr. Arkadin’s case, Arkadin’s secret remains his own. Harry Lime’s secrets are known, just an inconceivable and unforgivable shock.

Welles was a natural-born storyteller and an admitted fake whose showboatery materialized with brash external confidence. His undeniable talent usually validated his reputation, creating an odd hybrid of myth and man. Despite how many of his directorial projects went unfinished, or if completed, are now available in cuts he never approved of, he is nevertheless deemed a master by critics and film historians. Failure, no matter how grand for Welles, often resulted in critical praise. In fact, as a child, he was deemed a prodigy and would forever be thought of as the troubled, misunderstood genius. And perhaps whiz-kid is not too far off, given that Welles worked so idealistically out of Hollywood’s box as if he was an artist-child too young to realize Tinseltown has rules. In his amazingly edited documentary F for Fake (1973), Welles confesses that after failing to start a painting career, at the age of 16, he arrived in Dublin, Ireland. Having never acted a day, Welles told local talent scouts that he was a famous actor from New York. His stage career thus began, eventually bringing him back stateside to his white lie: New York City. Welles’ noted theater experience landed him regular spots on radio programs. The perfect allegory for Welles himself was his radio broadcast of H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds, a wonderfully conceived piece of broadcasting taken by many to be the truth. Welles’ October 30th, 1938 transmission featured reports of a Martian invasion intercut with authentic-sounding commercial breaks and music selections. It was believed authentic by uncountable radio patrons, causing widespread panic across New England, the broadcast’s purported locale of the Martian attack. Welles says in F for Fake that “People took to the hills. I met a welfare worker, years later, who told me he spent weeks trying to woo some of the refugees back to civilization.”

Welles was a natural-born storyteller and an admitted fake whose showboatery materialized with brash external confidence. His undeniable talent usually validated his reputation, creating an odd hybrid of myth and man. Despite how many of his directorial projects went unfinished, or if completed, are now available in cuts he never approved of, he is nevertheless deemed a master by critics and film historians. Failure, no matter how grand for Welles, often resulted in critical praise. In fact, as a child, he was deemed a prodigy and would forever be thought of as the troubled, misunderstood genius. And perhaps whiz-kid is not too far off, given that Welles worked so idealistically out of Hollywood’s box as if he was an artist-child too young to realize Tinseltown has rules. In his amazingly edited documentary F for Fake (1973), Welles confesses that after failing to start a painting career, at the age of 16, he arrived in Dublin, Ireland. Having never acted a day, Welles told local talent scouts that he was a famous actor from New York. His stage career thus began, eventually bringing him back stateside to his white lie: New York City. Welles’ noted theater experience landed him regular spots on radio programs. The perfect allegory for Welles himself was his radio broadcast of H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds, a wonderfully conceived piece of broadcasting taken by many to be the truth. Welles’ October 30th, 1938 transmission featured reports of a Martian invasion intercut with authentic-sounding commercial breaks and music selections. It was believed authentic by uncountable radio patrons, causing widespread panic across New England, the broadcast’s purported locale of the Martian attack. Welles says in F for Fake that “People took to the hills. I met a welfare worker, years later, who told me he spent weeks trying to woo some of the refugees back to civilization.”

Welles’ career contains the same authentic-sounding special effects (his filmic masterpieces), except he reinforces them through a series of fictions (his constant exaggeration in later interviews). These characteristics combine into Welles’ legend known as The Orson Welles, wholly believable, complete with an embellishment here and there. Like Welles, whose celebrity and myth are comprised of fact and fiction with magnificent results, Harry Lime’s entrance is assembled as a montage piece more impressive than the shower scene in Psycho (1960). The sequence was filmed by Guy Hamilton, following detailed notes provided by Reed. Buildings all around Vienna were included to create a filmic mirage of the depicted street; the setting shown does not actually exist—it’s a suggestion made through montage that creates the environment. A searchlight boosts the film’s dramatic, architecturally born shadows. A car passes after Martins spots Lime, though vehicles do not traditionally drive on such roads in Vienna. Lime sprints down an alley; we see a running shadow projected onto the alley wall, only it is not Welles doing the running; it’s Hamilton. Fragmented with glorious detail and edited together by Reed, the sequence showcases Welles and his Harry Lime as illusions of clever little lies. Moreover, it showcases the expert manipulation of the cinematic apparatus under Carol Reed.

In many ways, The Third Man is Welles’ victim. Not that the film itself suffers from his presence—quite the contrary—but rather, because it is unfortunate that so much talent is overlooked. The incomparable talent of Welles and the mystique of Harry Lime eclipse Carol Reed and Graham Greene’s achievements. This perhaps leads to a common misconception that Welles directed The Third Man, or at least had his hand in the creative processes of the production beyond his minor-but-memorable speech. Though it is somewhat hypocritical to begin wrapping up an appreciation of The Third Man on such a note, here the picture has been discussed primarily in the context of how it relates to Welles offscreen. But now, finally, in the end, Carol Reed’s importance must be stressed. Historians have written much about the picture and Welles’ onscreen allure, yet he is only a tiny part of Reed’s masterpiece. Take, for example, the film’s final scene where Alida Valli’s character Anna moves along a long stretch of cemetery road. Reed’s camera remains immobile for her long walk, and we watch as Anna makes her across almost fifty yards of the tree-lined path with Holly Martins waiting for her in the foreground, hoping for a romantic embrace. As Anna approaches, she walks right past Martins. This may be cinema’s greatest ending, owed entirely to Carol Reed for his insistence that it be filmed in a single shot.

In many ways, The Third Man is Welles’ victim. Not that the film itself suffers from his presence—quite the contrary—but rather, because it is unfortunate that so much talent is overlooked. The incomparable talent of Welles and the mystique of Harry Lime eclipse Carol Reed and Graham Greene’s achievements. This perhaps leads to a common misconception that Welles directed The Third Man, or at least had his hand in the creative processes of the production beyond his minor-but-memorable speech. Though it is somewhat hypocritical to begin wrapping up an appreciation of The Third Man on such a note, here the picture has been discussed primarily in the context of how it relates to Welles offscreen. But now, finally, in the end, Carol Reed’s importance must be stressed. Historians have written much about the picture and Welles’ onscreen allure, yet he is only a tiny part of Reed’s masterpiece. Take, for example, the film’s final scene where Alida Valli’s character Anna moves along a long stretch of cemetery road. Reed’s camera remains immobile for her long walk, and we watch as Anna makes her across almost fifty yards of the tree-lined path with Holly Martins waiting for her in the foreground, hoping for a romantic embrace. As Anna approaches, she walks right past Martins. This may be cinema’s greatest ending, owed entirely to Carol Reed for his insistence that it be filmed in a single shot.

And so, what an oddity that Welles overshadows the glory of The Third Man and its director with his minor role, just as Welles’ reputation now veils the man. If only Reed could escape from under the grate of Welles’ presence and take the credit he deserves for the film’s expressive atmosphere and lasting charm. But, alas, Reed is the shadowy figure standing under the arch in the doorway, obscured but crucial. Only when we explore the film’s production to consider the myth of Orson Welles and the hidden genius of the film’s director does the old lady across the way flip on her light and reveal that it is Reed standing in the doorway and not Welles. Reed informed his picture’s every cockeyed camera angle and chiaroscuro lighting effect, fought for the dignity of his story against Hollywood’s most powerful producer, integrated every curiously malformed detail, and set it all to Karas’ unforgettable zither music. Reed remains the picture’s greatest asset, even if he is not the first name that comes to mind when remembering The Third Man.

Bibliography:

Bazin, André. Orson Welles: a critical view. Foreword by François Truffaut; profile by Jean Cocteau; translated from the French by Jonathan Rosenbaum. Harper & Row, 1978.

Benamou, Catherine L. It’s all true: Orson Welles’s Pan-American Odyssey. University of California Press, 2007.

Drazin, Charles. In Search of The Third Man. Limelight Editions (Proscenium), 2000.

Evans, Peter William. Carol Reed. British Film Makers. Manchester University Press, 2005.

McBride, Joseph. Orson Welles. Da Capo Press, 1996.

Thomson, David. Rosebud: The Story of Orson Welles. Alfred A. Knopf, 1996.

Welles, Orson; Bogdanovich, Peter. This is Orson Welles. Edited by Jonathan Rosenbaum. Da Capo Press, 1998.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review