The Definitives

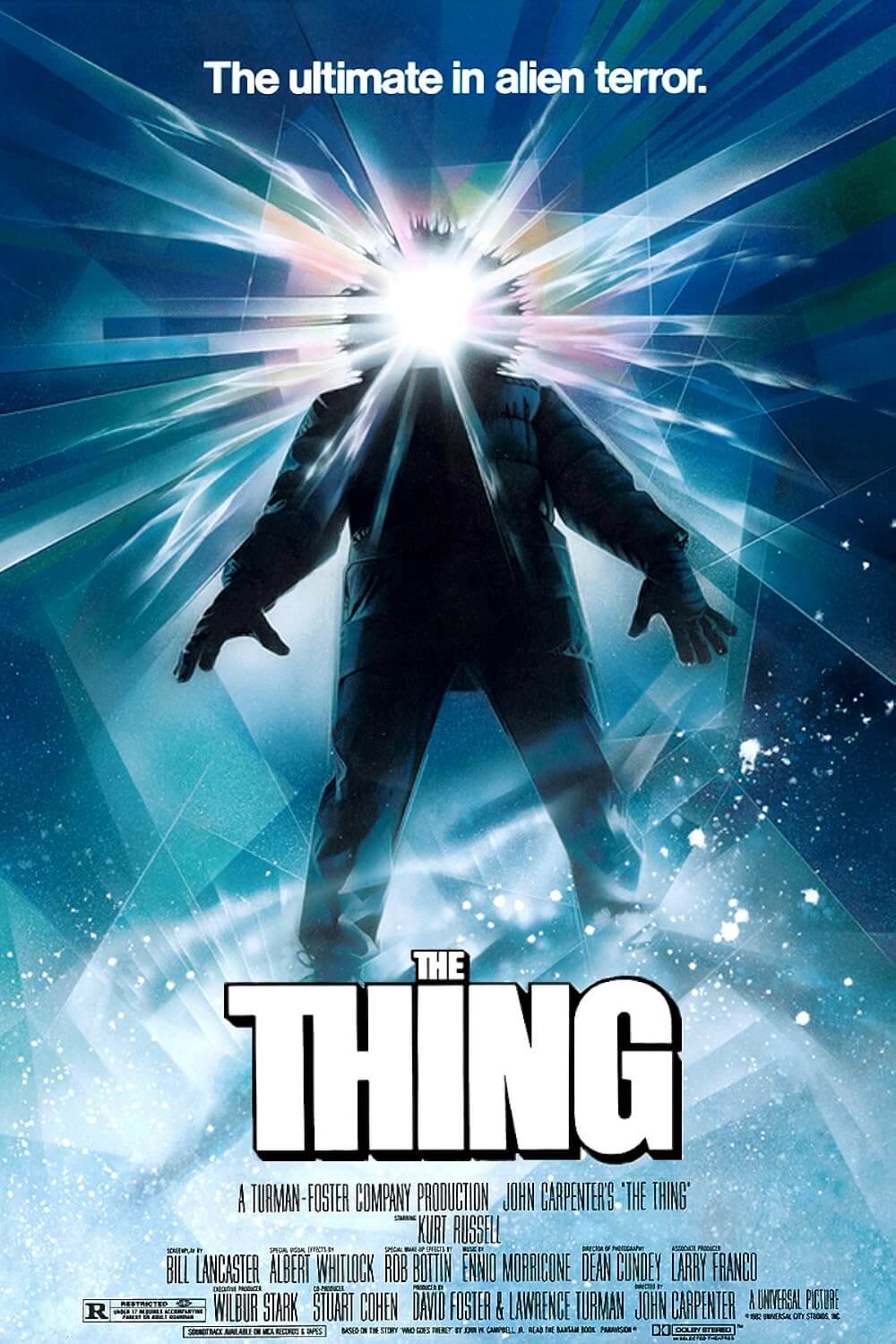

The Thing (1982)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

In the darkness loom horrible unknowns from our nightmares or from the blackest regions of our imagination, and in such unthinkable obscurity is where horror derives its greatest power. These fears retain their authority because as much as we try to comprehend what hides in the dark, we can never fully understand their form, those monsters and demons and things from beyond. Their veiled state preserves our fear by retaining anonymity; their presence is felt but exists within a vast and unknowable abyss. Frightening as these hidden creatures and trepidations may be, they never emerge, allowing their singular power over us to be fear, perhaps the most ultimate power of them all. And while we remain safe with their refusal to emerge, threatened only by these things as a concept, an idea, should those creatures burst into the light, our illusion of safety would disappear, and we would become susceptible not only to our own fear but to a reality so terrifying that our imaginations could not grasp its fantastical, horrifying truth. Testing the limitations of the horror genre, John Carpenter’s The Thing inhabits those shadowy places inside the human psyche and also emerges into frightening actuality.

Carpenter’s film was based on the 1938 novella Who Goes There? by John W. Campbell, Jr., who wrote under the pseudonym Don A. Stuart. The story was first published in the pulp magazine Astounding Science Fiction and involves an American research station tucked away in the spare, solitary landscape of the Antarctic. The isolated crew is exposed to an alien creature which has been buried in the ice for centuries, an organism that digests and replicates its victims, and then hides behind a perfect imitation of its prey. Without a distinct corporeal form, the alien emerges only when threatened, its appearance announced by a grotesque display of shifting physical transformations, an almost improvisational progression of flesh. Closely following its source, the very nature of the film’s alien threat defies and transcends typical horror tropes by leaping from the shadows not in any recognizable formation, such as a masked killer or an actor in an alien suit, and existing both in the realm of the disclosed and the unknown. Carpenter’s film is a rare horror masterwork of internal and external terror, an amazing display of practical special effects and understated performances, where the paranoid fear and suspicion of the man standing next to you is matched only by the graphic realization of that terror in its physical state.

Campbell’s story was originally adapted in 1951 by producer Howard Hawks into The Thing from Another World for RKO. Directorial credit went to Christian Nyby, however, the degree to which Hawks assumed directing duties over Nyby has long been the subject of many a cinéaste’s debate. Charles Lederer’s script takes place in the northern Arctic and represents the titular monster as a large vegetable-alien-thing, played by James Arness in a monster suit, inspired by Frankenstein’s monster, complete with defined humanoid features instead of the shape-shifting creature described in Who Goes There?. Hawks himself purchased the rights to Campbell’s story and developed the film in his classicized style, where a group of men set out to perform acts of heroism, protecting the resident woman (Margaret Sheridan) and defeating the alien. Lederer’s script leaves out the suspicions and questions about identity that were so prevalent in Campbell’s tale, relying on the single-minded man vs. alien conflict present in so many 1950s sci-fi films. As often as Carpenter’s film is called a remake for paying homage to The Thing from Another World, Hawks’ production substantially diverts from the source material, whereas Carpenter remains faithful to Campbell’s intangible cellular foundation for the alien intruder.

Campbell’s story was originally adapted in 1951 by producer Howard Hawks into The Thing from Another World for RKO. Directorial credit went to Christian Nyby, however, the degree to which Hawks assumed directing duties over Nyby has long been the subject of many a cinéaste’s debate. Charles Lederer’s script takes place in the northern Arctic and represents the titular monster as a large vegetable-alien-thing, played by James Arness in a monster suit, inspired by Frankenstein’s monster, complete with defined humanoid features instead of the shape-shifting creature described in Who Goes There?. Hawks himself purchased the rights to Campbell’s story and developed the film in his classicized style, where a group of men set out to perform acts of heroism, protecting the resident woman (Margaret Sheridan) and defeating the alien. Lederer’s script leaves out the suspicions and questions about identity that were so prevalent in Campbell’s tale, relying on the single-minded man vs. alien conflict present in so many 1950s sci-fi films. As often as Carpenter’s film is called a remake for paying homage to The Thing from Another World, Hawks’ production substantially diverts from the source material, whereas Carpenter remains faithful to Campbell’s intangible cellular foundation for the alien intruder.

Carpenter had been thinking about a new version of Who Goes There? since 1975, when he and co-producer Stuart Cohen first discussed the idea of a film that concentrates on the alien’s ability to replicate its victims. After the huge box-office success of Ridley Scott’s Alien in 1979, the proposition of slimy monsters from outer space was commercially viable and, given Carpenter’s own independent smash Halloween in 1978, Universal Studios green lit the proposed new adaptation of Campbell’s novella. Bill Lancaster (son of actor Burt Lancaster) wrote the screenplay and reduced the author’s more than thirty characters down to an economic twelve. Distinct from The Thing from Another World, there are no female characters in Lancaster’s script, which adheres to the source material’s roster of an all-male crew. “In reality there aren’t any women in these kinds of situations,” Lancaster told Starlog in 1982. “It seemed more honest to have a group of men in that situation.” Although Carpenter generally avoids such stereotypes, a woman’s lot in horror films is usually that of a kidnappee or screaming damsel, with both Alien and Halloween being exceptions. Nevertheless, Lancaster’s very male script removes all hints of sexual politics to focus on a group of men whose ostensible asexuality emphasizes the film’s themes of entrenched paranoia, survival, and identity.

Following Campbell’s source material, Carpenter approaches the alien as an organism able to reproduce human behavior without flaw. Victims are seemingly digested and replicated by the alien, leaving anyone in the Antarctic camp vulnerable to exposure, thus making everyone a suspected alien. In the first scenes, what seems to be a frightened Siberian Husky is chased onto the site by the last two surviving crewmembers from a nearby Norwegian science camp, who are summarily killed for their apparent irrational, cabin-feverish need to destroy the dog. Hours later, the dog reveals the alien’s modus operandi when the Husky attempts to absorb the Americans’ dogs while locked in the station’s kennel. The American crew rushes to the sound of howling canines, and what they see is a creature steeped in viscera, tendrils and teeth and eyes and arms, without a set structure and seeking to hide within the form of another. Though they attempt to destroy it with fire, each individual cell is its own organism with the ability to overtake victims. Isolated by miles of harsh terrain and the onset of winter, the Americans have no way of knowing who “The Thing” has since converted and who remains human. Any one of them could be an alien in disguise. There’s even some question about whether or not an imitation would know that it’s an imitation. But before Carpenter and Lancaster fuel our paranoia, they build subtle characterization and unbearable anticipation for The Thing’s arrival.

Following Campbell’s source material, Carpenter approaches the alien as an organism able to reproduce human behavior without flaw. Victims are seemingly digested and replicated by the alien, leaving anyone in the Antarctic camp vulnerable to exposure, thus making everyone a suspected alien. In the first scenes, what seems to be a frightened Siberian Husky is chased onto the site by the last two surviving crewmembers from a nearby Norwegian science camp, who are summarily killed for their apparent irrational, cabin-feverish need to destroy the dog. Hours later, the dog reveals the alien’s modus operandi when the Husky attempts to absorb the Americans’ dogs while locked in the station’s kennel. The American crew rushes to the sound of howling canines, and what they see is a creature steeped in viscera, tendrils and teeth and eyes and arms, without a set structure and seeking to hide within the form of another. Though they attempt to destroy it with fire, each individual cell is its own organism with the ability to overtake victims. Isolated by miles of harsh terrain and the onset of winter, the Americans have no way of knowing who “The Thing” has since converted and who remains human. Any one of them could be an alien in disguise. There’s even some question about whether or not an imitation would know that it’s an imitation. But before Carpenter and Lancaster fuel our paranoia, they build subtle characterization and unbearable anticipation for The Thing’s arrival.

The American crewmembers are painted with minimalist yet ingeniously reserved and detailed brushstrokes, each developed but kept at a distance to retain the film’s agonizing sense of claustrophobic autophobia. None of the crew members feel arbitrary, though each contains equally ambiguous mannerisms. The ensemble includes distinguished film and theater performers and no extras, just the twelve male actors: the rugged loner MacReady (Kurt Russell) is one of two helicopter pilots; the other is the pothead Palmer (David Clennon); there’s the pensive doctor Blair (Wilford Brimley); Copper (Richard Dysart) is a nose-pierced medic; Clark (Richard Masur) is the dog handler who seems to prefer his dogs to his fellow crewmembers; Nauls (T.K. Carter) is the lighthearted cook; Windows (Thomas Waites) is the nervy radio operator; Fuchs (Joel Polis) is an inquisitive scientific mind; Bennings (Peter Maloney) is a fussy sort; their quiet captain is Garry (Donald Moffat); Norris (Charles Hallahan) is the pudgy second-in-command who turns down the chance to take over when Garry gives up his leadership; and Childs (Keith David) is the tough, imposing figure of the group. The distinctive cast became a collective during filming, complete with the natural camaraderie one might expect from a group of men shooting a horror movie in the deep cold of British Columbia. Polis described the cast as little boys playing with guns and helicopters and monsters, and he considered the entire experience an exercise in male bonding. Their comfortable naturalism translates to the screen; their physical “types”, as they are, remain dissimilar from one another and their personalities never overstated.

To work in the Antarctic requires tolerance for isolation, which in turn requires personalities not sewn into an extroverted social fabric. The Antarctic crew is civil, quiet, and outwardly remote, choosing their work because seclusion remains a non-issue. They’re social enough, playing ping-pong, pool, and cards with one another in an early sequence. Meanwhile, the film’s hero MacReady is first seen alone in his shack, playing chess against a computer and drinking scotch. The female-voiced computer program wins, and Mac pours his drink on her circuits and mutters, “Cheating bitch.” Lancaster’s screenplay describes Mac as “Thirty-five. Helicopter pilot. Likes chess. Hates the cold. The pay is good,” suggesting the character is spartan, a thinker, and sore loser (which is mirrored later in the finale). That he’s willing to destroy the computer boards when he loses implies he’s a cynic and capable of self-destruction when faced with an impossible situation. MacReady chooses to be alone, even when cut off from the rest of the world. Overall, the crew’s distant personalities provide enough doubt that the viewer cannot identify in which body the alien hides. The men exist not as horror movie clichés with background stories or forced character identifiers embedded into their dialogue—they are austere, each a pure expression of simplicity.

To work in the Antarctic requires tolerance for isolation, which in turn requires personalities not sewn into an extroverted social fabric. The Antarctic crew is civil, quiet, and outwardly remote, choosing their work because seclusion remains a non-issue. They’re social enough, playing ping-pong, pool, and cards with one another in an early sequence. Meanwhile, the film’s hero MacReady is first seen alone in his shack, playing chess against a computer and drinking scotch. The female-voiced computer program wins, and Mac pours his drink on her circuits and mutters, “Cheating bitch.” Lancaster’s screenplay describes Mac as “Thirty-five. Helicopter pilot. Likes chess. Hates the cold. The pay is good,” suggesting the character is spartan, a thinker, and sore loser (which is mirrored later in the finale). That he’s willing to destroy the computer boards when he loses implies he’s a cynic and capable of self-destruction when faced with an impossible situation. MacReady chooses to be alone, even when cut off from the rest of the world. Overall, the crew’s distant personalities provide enough doubt that the viewer cannot identify in which body the alien hides. The men exist not as horror movie clichés with background stories or forced character identifiers embedded into their dialogue—they are austere, each a pure expression of simplicity.

Composed by Ennio Morricone (The Good, the Bad and the Ugly), the film’s discreet music helps further isolate the viewer and wind up the suspense with its swelling tones. Carpenter, who often creates the music for his films, added some electronic inclusions during post-production to augment the effect. The music is evident primarily in the first third of the film, where The Thing has not yet emerged in full form. Events unfold onscreen with an almost mythic quality early on, such as Mac and Copper visiting the Norwegian camp and witnessing the destruction and death caused by something, or the American crew watching the Norwegian videos of how they found a flying saucer under the ice. Morricone’s music provides a steady heartbeat tempo to reflect the film’s deliberately paced momentum; the outcome recedes into the background, as if the score were an ongoing, percussion-based pulse. Had he scored the picture with grandiose notes punctuating every emotion or thrill, the audience would have lost their sense of isolation, the feeling that something is horribly wrong in the Antarctic camp. Indeed, that we barely notice the Morricone-Carpenter score places the viewer within the film’s draining, vacant environment, susceptible to each ensuing shock to emerge from the calm.

Once The Thing arrives and everyone witnesses how it behaves with the dogs, Blair calculates the possibilities that some of their crew has already been infected, and then potential worldwide contamination. Coming to a grim conclusion, he destroys all radios and transportation, hoping to quarantine the threat. After subduing the panicky Blair, the crew agrees to lock him away in a storage shed, keeping him separated from the others in fear of his potential exposure. Wrought with paranoia, familiar faces become suspect. Anyone could be more than what they seem, and so every individual is reduced to just that. As Mac observes, “Trust is a tough thing to come by these days.” Having had the alien’s chameleon potential described to them by Blair, and having seen the charred remains of a Thing-human hybrid leftover from the Norwegian camp, none of the station’s crew grasp the exactness of the monster in their midst. Only after Windows walks in on the alien consuming Bennings and warns the others does everyone see the alien’s potential first-hand. The group gathers, following “Bennings” outdoors. The creature’s digestion incomplete, “Bennings” looks wholly human, save for his freakishly elongated digits and the blood-curdling moan it lets out. Encircling what appears to be their former friend, together they witness the horrible possibility behind the alien’s replication process. Who else among them has been turned since the Husky first arrived?

Once The Thing arrives and everyone witnesses how it behaves with the dogs, Blair calculates the possibilities that some of their crew has already been infected, and then potential worldwide contamination. Coming to a grim conclusion, he destroys all radios and transportation, hoping to quarantine the threat. After subduing the panicky Blair, the crew agrees to lock him away in a storage shed, keeping him separated from the others in fear of his potential exposure. Wrought with paranoia, familiar faces become suspect. Anyone could be more than what they seem, and so every individual is reduced to just that. As Mac observes, “Trust is a tough thing to come by these days.” Having had the alien’s chameleon potential described to them by Blair, and having seen the charred remains of a Thing-human hybrid leftover from the Norwegian camp, none of the station’s crew grasp the exactness of the monster in their midst. Only after Windows walks in on the alien consuming Bennings and warns the others does everyone see the alien’s potential first-hand. The group gathers, following “Bennings” outdoors. The creature’s digestion incomplete, “Bennings” looks wholly human, save for his freakishly elongated digits and the blood-curdling moan it lets out. Encircling what appears to be their former friend, together they witness the horrible possibility behind the alien’s replication process. Who else among them has been turned since the Husky first arrived?

As rampant distrust floods the camp, the alien’s most affront weapon is suspicion and events around the camp only heighten our fear. Before the dogs were attacked, we saw the Husky enter someone’s room at night; now we know one of them must have turned. Torn clothes which seem to indicate the creature’s attack are found in Nauls’ kitchen. Someone destroys the camp’s blood stock, fearing its usage in a test to expose the alien(s) among them. As a result, they no longer trust their leader, Garry, who along with Copper had access to the blood, suggesting that they both may have turned. With inoperative radios and an Antarctic winter leaving them unable to signal for help, their isolation is complete. They dread close proximity to one another, yet are afraid to isolate themselves. We question even the protagonist, Mac, whose humanness becomes suspect when someone finds his torn clothes hidden away, suggesting his exposure and subsequent replication. Turning into a small mob, with their misgivings serving as rationality, MacReady becomes their target to be lynched. During the commotion, Norris drops to the ground, seemingly of a heart attack, and prevents Mac from having to ignite dynamite to protect himself.

“What I didn’t want to end up with in this movie was a guy in a suit,” said Carpenter of his vision for The Thing’s creature. “See, I grew up as a kid watching science-fiction and monster movies and it was always a guy in a suit,” he explained. Working closely with his creature effects designer Rob Bottin, Carpenter embraced Bottin’s recommendation for an alien that has no set form. When exposed, the alien would not reveal itself as a veggie version of Frankenstein’s monster, rather an abstract of twisting flesh, slimy tentacles, and indiscernible parts, all moving quickly with infinite layers to assimilate its prey, and slathered and dripping in Bottin’s vigorous application of slime made from K-Y Jelly. Bottin’s conceptual agenda supports Carpenter’s cinematic thesis by exposing perceptions usually obscured within horror filmmaking, and yet the director retains his ability to involve his audience. Normally hidden behind a mask, by concealing camerawork, or inside a film’s mise-en-scène, gory horror rarely engages an audience on any lasting level, serving instead as shock value. Horror movies often contain pangs of gore and violence, infrequent but sharp, though they seldom prolong any direct exposure. When a movie embraces an onslaught of ultra-violence (example: Wes Craven’s The Last House on the Left), the audience becomes disconnected from the narrative (Craven’s film even used the tagline “It’s only a movie,” so audiences might get through the proceedings by repeating the phrase in their heads, disconnecting themselves from the events onscreen). But The Thing’s scares are delivered between scenes about growing paranoia to avoid overexposure and therein never remove the audience from the ongoing narrative due to pervasive gore. Instead, each revealing explosion of alien monstrosity works harmoniously with, versus superior to, the characters’ revolving suspicion.

“What I didn’t want to end up with in this movie was a guy in a suit,” said Carpenter of his vision for The Thing’s creature. “See, I grew up as a kid watching science-fiction and monster movies and it was always a guy in a suit,” he explained. Working closely with his creature effects designer Rob Bottin, Carpenter embraced Bottin’s recommendation for an alien that has no set form. When exposed, the alien would not reveal itself as a veggie version of Frankenstein’s monster, rather an abstract of twisting flesh, slimy tentacles, and indiscernible parts, all moving quickly with infinite layers to assimilate its prey, and slathered and dripping in Bottin’s vigorous application of slime made from K-Y Jelly. Bottin’s conceptual agenda supports Carpenter’s cinematic thesis by exposing perceptions usually obscured within horror filmmaking, and yet the director retains his ability to involve his audience. Normally hidden behind a mask, by concealing camerawork, or inside a film’s mise-en-scène, gory horror rarely engages an audience on any lasting level, serving instead as shock value. Horror movies often contain pangs of gore and violence, infrequent but sharp, though they seldom prolong any direct exposure. When a movie embraces an onslaught of ultra-violence (example: Wes Craven’s The Last House on the Left), the audience becomes disconnected from the narrative (Craven’s film even used the tagline “It’s only a movie,” so audiences might get through the proceedings by repeating the phrase in their heads, disconnecting themselves from the events onscreen). But The Thing’s scares are delivered between scenes about growing paranoia to avoid overexposure and therein never remove the audience from the ongoing narrative due to pervasive gore. Instead, each revealing explosion of alien monstrosity works harmoniously with, versus superior to, the characters’ revolving suspicion.

A wonder of makeup and puppet artistry, Bottin conceived the film’s most visually impressive, technically complicated sequence, involving the rush to save Norris from his apparent heart attack. In the scene, Dr. Copper pumps the unconscious Norris with defibrillation paddles until all at once the patient’s chest cavity caves in, revealing teeth at its edge. The toothed opening closes down on Copper, now played by an armless stunt double wearing a Richard Dysart mask, which allowed Bottin to show the alien biting off the doctor’s arms. From inside Norris’ torso, a slimy, massive protrusion with a long ribbed neck leading to a second screaming Norris head ruptures upward and clings to an overhead air duct with crab-like legs. The Norris head still attached to the torso waves back and forth slowly, separating so veins pull and stretch and disconnect in a gooey green mess onto the floor; its tongue wraps around a chair to drag itself clear of the greater torso, which is blowtorched by Mac. On the floor, Norris’ remaining head grows stalk-like legs and two tentacles on, the end of which are eyes, and the spidery assemblage attempts to scamper out into the hallway. The crew looks in amazement as Norris’ head-creature scuttles away. Palmer remarks, “You gotta be fuckin’ kidding.” And then Mac sets it ablaze.

Bottin’s concept for The Thing in this sequence illustrates each piece of the alien branching out and defending itself; the whole becomes an indescribable sum of individuals, rather than a single organism hiding within a host. Bottin told Cinefantastique in 1982, “Since The Thing had been all over the galaxy, it could call upon anything it needed whenever it needed.” Lit without restraint and shot in detail by Carpenter’s frequent early career cinematographer Dean Cudney, the scene’s vivid clarity allows Bottin’s creation to burst off the screen, unafraid to expose its explicit, true fleshy colors, unlike other horror films so dependent on the dark. Carpenter does something revolutionary by photographing the monster without limiting the scene’s light. Before the age of glimmeringly artificial computer-generated images, effects wizards built their creations out of foam rubber, latex, corn syrup, fiberglass, chemicals, the aforementioned sexual lubricant, and any number of available materials needed to breathe physical life into their movie monsters, but then hid their creatures in dim lighting. Having apprenticed under makeup guru Rick Baker (An American Werewolf in London), Bottin wowed Carpenter with his effects on The Howling and The Fog. His expertise would be drained on this project, perfecting various edifices of The Thing for months upon months so they didn’t need low light to hide their artifice. His all-consuming task even landed him in the hospital with exhaustion. In Bottin’s absence, Stan Winston’s effects company, responsible for Aliens and Terminator 2: Judgment Day, agreed to complete the film’s memorably grotesque dog assimilation sequence.

Bottin’s concept for The Thing in this sequence illustrates each piece of the alien branching out and defending itself; the whole becomes an indescribable sum of individuals, rather than a single organism hiding within a host. Bottin told Cinefantastique in 1982, “Since The Thing had been all over the galaxy, it could call upon anything it needed whenever it needed.” Lit without restraint and shot in detail by Carpenter’s frequent early career cinematographer Dean Cudney, the scene’s vivid clarity allows Bottin’s creation to burst off the screen, unafraid to expose its explicit, true fleshy colors, unlike other horror films so dependent on the dark. Carpenter does something revolutionary by photographing the monster without limiting the scene’s light. Before the age of glimmeringly artificial computer-generated images, effects wizards built their creations out of foam rubber, latex, corn syrup, fiberglass, chemicals, the aforementioned sexual lubricant, and any number of available materials needed to breathe physical life into their movie monsters, but then hid their creatures in dim lighting. Having apprenticed under makeup guru Rick Baker (An American Werewolf in London), Bottin wowed Carpenter with his effects on The Howling and The Fog. His expertise would be drained on this project, perfecting various edifices of The Thing for months upon months so they didn’t need low light to hide their artifice. His all-consuming task even landed him in the hospital with exhaustion. In Bottin’s absence, Stan Winston’s effects company, responsible for Aliens and Terminator 2: Judgment Day, agreed to complete the film’s memorably grotesque dog assimilation sequence.

Between Bottin and Winston, the effects in The Thing proved so gristly that few critics could see beyond them when the film was released in 1982. In New York magazine, critic David Denby wrote, “This movie is more disgusting than frightening.” Roger Ebert called it “a great barf-bag movie” and went on to deem it “a geek show, a gross-out movie in which teenagers can dare one another to watch the screen.” But then, Carpenter’s film was released just two weeks after Steven Spielberg’s decisive hit E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial landed in theaters not only to break box-office records of the time, but to implant audiences and critics with a sudden syrupy outlook on potential alien life forms visiting Earth. Carpenter’s film is the antithesis of Spielberg’s film, suggesting with his alien visitation that an apocalypse hangs in the balance, purveyed by a creature without a singular form or cutesy human mannerisms. Carpenter recollected, “You must remember the time it was released… And it was a very bleak and hopeless film. There were no women in the movie, and people thought I went too far.” Though almost universally panned in 1982, over the years The Thing has undergone reassessment following its rediscovery on video and cable, an emergence from a cult phenomenon into bona fide horror classic; today Carpenter’s film is generally considered his masterpiece, even by the director himself.

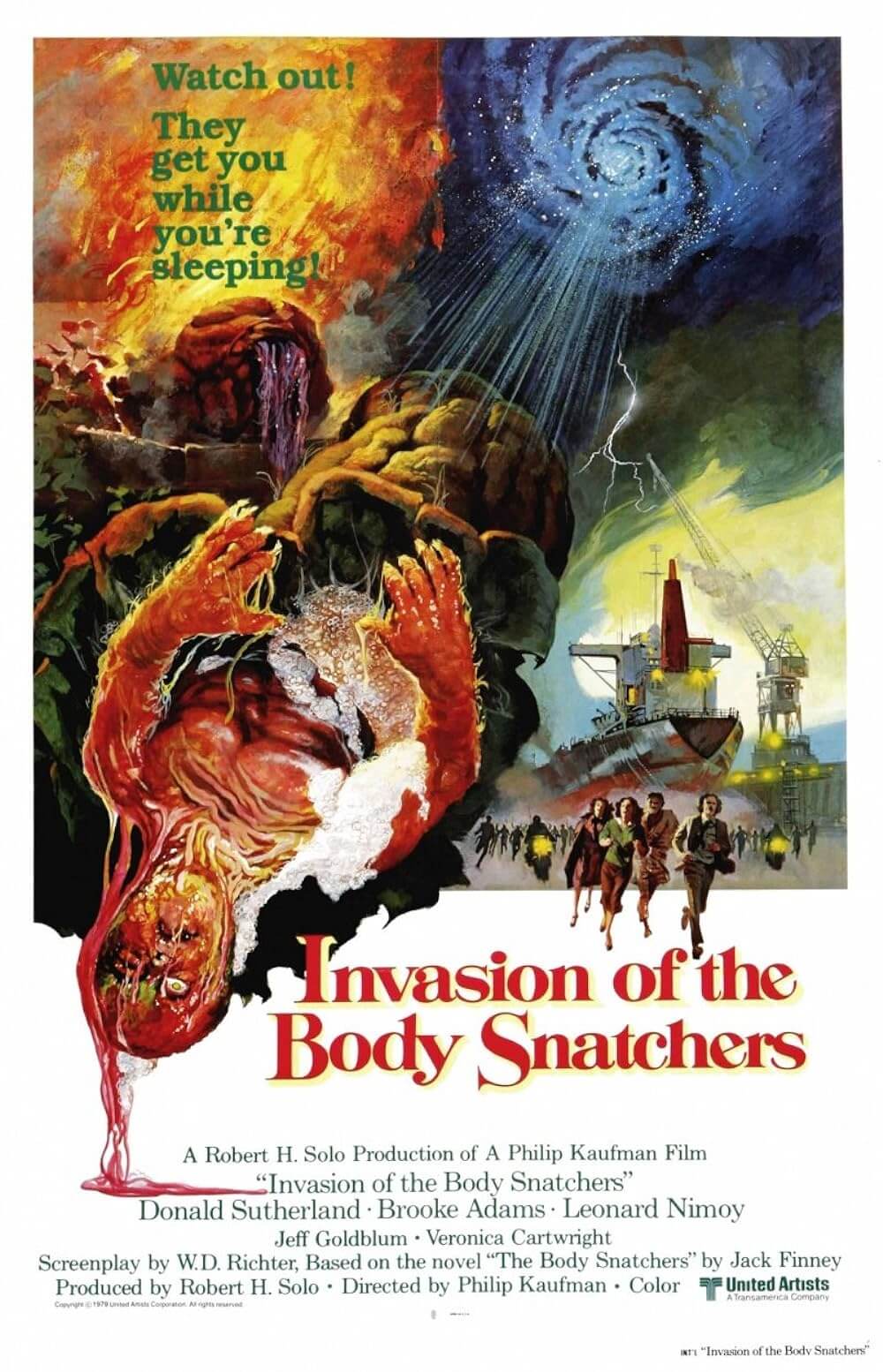

Many critics deemed The Thing a knock-off of Alien, and while the two films share a Ten Little Indians scenario, the aliens themselves couldn’t be more different. Where the H.R. Giger creation hunted like an insectoid predator, The Thing wants to merge with its victims and hide in their form; they conceal themselves and slowly take control much like the aliens in Philip Kaufman’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978), which when exposed reach out and scream a shrill alarm to its fellow invaders. Of course, The Thing’s reaction to exposure is far more violent and disturbing, but its raison d’être is the same. And because The Thing’s imitations are so precise, we are forced to ask philosophical questions: Does The Thing represent some political ideology such as McCarthyism or just sheer blind conformity? Does someone know when they’re The Thing? Could someone be an alien and be unaware of it? Consider Norris before his heart attack—when he’s looking out the window for Mac and Nauls, and how as he announces to everyone to come and look, he gets a sharp pain in his stomach. He gives a surprised “ouch” expression, as though something is happening inside his body and he’s not sure what. Has he retained his identity, despite, in retrospect, the audience knowing he’s been turned? Could The Thing’s process of imitation be so completely perfect that its victim preserves their identity? And if the imitation is that exact, could being an imitation be so bad?

Many critics deemed The Thing a knock-off of Alien, and while the two films share a Ten Little Indians scenario, the aliens themselves couldn’t be more different. Where the H.R. Giger creation hunted like an insectoid predator, The Thing wants to merge with its victims and hide in their form; they conceal themselves and slowly take control much like the aliens in Philip Kaufman’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978), which when exposed reach out and scream a shrill alarm to its fellow invaders. Of course, The Thing’s reaction to exposure is far more violent and disturbing, but its raison d’être is the same. And because The Thing’s imitations are so precise, we are forced to ask philosophical questions: Does The Thing represent some political ideology such as McCarthyism or just sheer blind conformity? Does someone know when they’re The Thing? Could someone be an alien and be unaware of it? Consider Norris before his heart attack—when he’s looking out the window for Mac and Nauls, and how as he announces to everyone to come and look, he gets a sharp pain in his stomach. He gives a surprised “ouch” expression, as though something is happening inside his body and he’s not sure what. Has he retained his identity, despite, in retrospect, the audience knowing he’s been turned? Could The Thing’s process of imitation be so completely perfect that its victim preserves their identity? And if the imitation is that exact, could being an imitation be so bad?

Such philosophical questions linger just under the surface of Carpenter’s film, however, the director never sacrifices his grueling tension to stop and ask them, nor does he need to. After the crew sees how The Thing worked on Norris, the very next scenes show the crew wrought by emotional uncertainties while the viewer’s mind reels with questions. With Norris’ transformation scarred in the crew’s thoughts, they look at each other with guarded, suspicious eyes. Who else, they wonder, has been compromised? MacReady develops the idea for the film’s most frightening sequence, one taken directly from Campbell’s novella: Mac ties down the entire crew, takes blood samples, and exposes their blood to a wire heated by his blowtorch—his theory being that each part of The Thing has an individual physiology, and when burned it will crawl away. Each test involves unbearable suspense; the subjects watch Mac, afraid of what their own test might determine, unsure of even their own humanity. Draining his blood into a Petri dish, Mac proves his humanness. Upon each negative result, he frees the subject. Listen to the low sounds amid otherwise menacing silence: the hum of the blowtorch heating the wire again, the sizzle of the wire in blood, and the eventual screech of the creature when exposed—sounds onto which we cling (or jump from) under Carpenter’s flawless management. Throughout, the director relies on simple master shots and an expert use of his widescreen frame, his style unassuming and pacing deliberate to fuel our paranoia until it fills the vast space between characters.

Several of Carpenter’s films are about unknown fears that burst from the shadows into reality. Such fears often exist on the border between indefinite horrors and physically realized monstrosities, which is perhaps why his pictures remain so unforgettably engaging. In Halloween, for example, the impetus behind babysitter slasher Michael Myers goes unexplained except to be, as Donald Pleasence’s Dr. Loomis explains, “purely and simply… evil.” Throughout Halloween’s script, co-writers Carpenter and Debra Hill refer to Myers as “The Shape”, an otherwise unidentified incarnation of evil representing something more ethereal than a disturbed mind, and yet he exists in a physical form. Carpenter’s The Fog (1980) considered an entire town under siege by a blanket of eerie supernatural fog, inside of which shadowy, gruesome figures with glowing eyes seek revenge, the entire film reliant on the director’s balance of real and perceived fear. In Prince of Darkness (1987), Carpenter finds a tangible basis for horror behind two intangible ideas of religion and quantum physics when a group of scientists set out to prove the devil exists. An ode to H.P. Lovecraft, Carpenter’s In the Mouth of Madness (1994) concerns what happens when reality becomes less real to the masses than the imagination of a best-selling horror author. These and other films by the director investigate the boundary between our fears and their physical manifestation.

Several of Carpenter’s films are about unknown fears that burst from the shadows into reality. Such fears often exist on the border between indefinite horrors and physically realized monstrosities, which is perhaps why his pictures remain so unforgettably engaging. In Halloween, for example, the impetus behind babysitter slasher Michael Myers goes unexplained except to be, as Donald Pleasence’s Dr. Loomis explains, “purely and simply… evil.” Throughout Halloween’s script, co-writers Carpenter and Debra Hill refer to Myers as “The Shape”, an otherwise unidentified incarnation of evil representing something more ethereal than a disturbed mind, and yet he exists in a physical form. Carpenter’s The Fog (1980) considered an entire town under siege by a blanket of eerie supernatural fog, inside of which shadowy, gruesome figures with glowing eyes seek revenge, the entire film reliant on the director’s balance of real and perceived fear. In Prince of Darkness (1987), Carpenter finds a tangible basis for horror behind two intangible ideas of religion and quantum physics when a group of scientists set out to prove the devil exists. An ode to H.P. Lovecraft, Carpenter’s In the Mouth of Madness (1994) concerns what happens when reality becomes less real to the masses than the imagination of a best-selling horror author. These and other films by the director investigate the boundary between our fears and their physical manifestation.

In her vital essay on The Thing for the BFI Modern Classics series, author Anne Billson argues in a “fanciful if rather diverting reading” of the film that the alien creature represents femininity. The pointed lack of women in Lancaster’s script then suggests the all-male crew is in a battle against a femme fatale monster shrouded in mystery and capable of birthing new life from a single cell. Billson writes, “She gets under a man’s skin, smothers him in her weird discharge, saps his free will until, horror of horrors, he ceases to be a man.” The monster even takes on a vagina dentata form when Norris’ chest breaks open into a diamond-shaped cavity with teeth. Later in the film we see male inadequacy on full display when Windows fails to ignite his flamethrower and his head ends up in the monster’s jaws, whereas our manly hero Mac uses his flamethrower to destroy one variant of The Thing in a fiery, ejaculatory blaze. And while a complete reading of The Thing on these terms comes to some thin but fascinating conclusions about the film’s absence of sexuality and the general fear of castration throughout, Billson’s argument illustrates the illusory nature of the beast in the film—that it could represent anything from anywhere and who could argue, because after all What is it?

In the end, Mac finds himself alone, seemingly the camp’s sole survivor after he detonates enough dynamite to send the entire station, and The Thing with it, up into flames. Resting under a blanket with a bottle of scotch and watching it all burn, Mac sees Childs emerge from the night, somehow alive. Childs explains how earlier in the evening he saw Blair and chased him into the blizzard and got lost, though Mac is understandably suspicious. “If we’ve got any surprises for each other, I don’t think we’re in much shape to do anything about it,” Mac says in a resigned tone. “Why don’t we just wait here a little while, see what happens?” Then he passes Childs his scotch and seems to chuckle to himself. The last few lines of dialogue, which were written by Kurt Russell, imply that perhaps one of the two survivors may be The Thing. To be sure, Carpenter frequently refers to The Thing, Prince of Darkness, and In the Mouth of Madness as his unofficial “Apocalypse Trilogy”. Each film contains an End of Days scenario signifying the vulnerability of the human body and mind. Though Carpenter himself has said The Thing represents an allegory for whatever the audience chooses—be it disease, political metaphor, or castration anxiety—he always underlines the doomed nature of humankind to enhance our fear.

In the end, Mac finds himself alone, seemingly the camp’s sole survivor after he detonates enough dynamite to send the entire station, and The Thing with it, up into flames. Resting under a blanket with a bottle of scotch and watching it all burn, Mac sees Childs emerge from the night, somehow alive. Childs explains how earlier in the evening he saw Blair and chased him into the blizzard and got lost, though Mac is understandably suspicious. “If we’ve got any surprises for each other, I don’t think we’re in much shape to do anything about it,” Mac says in a resigned tone. “Why don’t we just wait here a little while, see what happens?” Then he passes Childs his scotch and seems to chuckle to himself. The last few lines of dialogue, which were written by Kurt Russell, imply that perhaps one of the two survivors may be The Thing. To be sure, Carpenter frequently refers to The Thing, Prince of Darkness, and In the Mouth of Madness as his unofficial “Apocalypse Trilogy”. Each film contains an End of Days scenario signifying the vulnerability of the human body and mind. Though Carpenter himself has said The Thing represents an allegory for whatever the audience chooses—be it disease, political metaphor, or castration anxiety—he always underlines the doomed nature of humankind to enhance our fear.

The Thing might represent any number of threats that could destroy civilization. But the film is not about what The Thing symbolizes; rather, it’s about the unrelenting acknowledgment that such a threat exists and, whether its form is psychological or physical, humans should be afraid. With the film’s ending, Carpenter avoids playing make-believe by telling us all will be well, or returning the viewer to safety by eliminating all traces of the threat. More even than the alien creatures represented in the film, the simple idea that we are not safe survives long after Carpenter’s masterpiece has ended. The Thing’s brilliance rests on the equilibrium between implied and visceral horror, often incompatible ideas that Carpenter stirs together in a stylish, engrossing way. Because The Thing lingers in the darkness of inscrutability within a human guise or an unknowable monster form, we are nearly broken by the suspense of its coming, which the director maintains for much longer than any other filmmaker could hold. When the terror arrives, horrifying monster effects manifest with profoundly grotesque, visceral shape and therein preserve a lasting place in our memory and our nightmares even after they are no longer onscreen. Escaping into some safe place remains impossible; the dangers are both within and without, forcing us to cross into uncomfortable zones swelling with both psychological and physical horror most directors would be afraid to explore at the same time. But not John Carpenter.

Bibliography:

Billson, Anne. The Thing. British Film Institute Modern Classics, BFI Publishing, 1997.

Boulenger, Gilles. John Carpenter: The Prince of Darkness. Spakenburg : H.O.M. Vision, 2002.

Carroll, Noel. The Philosophy of Horror. Routledge, 1990.

John Carpenter’s The Thing: Terror Takes Shape. Dir. Michael Matessino. DVD. Universal, 1998.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review