The Definitives

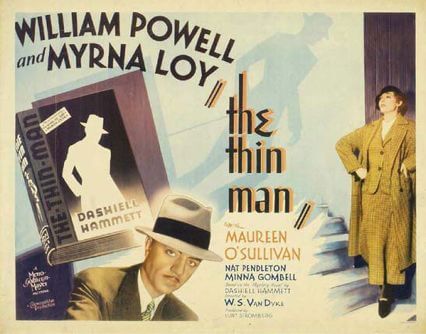

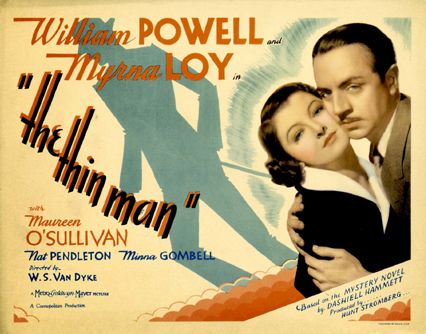

The Thin Man (1934)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

On the surface, The Thin Man is about retired detective Nick Charles, played by the debonair William Powell, who investigates a missing person’s case and, in due course, solves a twisting, almost incomprehensible murder mystery. But if the mystery is essential to the plot, it’s only because it affords an excuse to explore the blithe marriage of Nick and Nora Charles. With Powell’s onscreen wife played by Myrna Loy, the actor’s most recurrent costar, no other performers could have played Nick and Nora and given them such infectious charm. Ever bantering in endearing quips and flirtations, Nick and Nora are unsaddled by the typical responsibilities and concerns inherent to movie marriages; there are no children, infidelities, financial constraints, or domestic troubles of any kind. The happy couple remains unshakable in their playful adoration for one another, their primary concerns centered on their dog Asta and maintaining their party lifestyle. We first meet Nick as he teaches a bartender to mix a dry martini. “The important thing is rhythm,” Nick explains. “You always shake to waltz time.” Nora shows up a little later with Asta leading her forward on the leash, her unforgettable entrance marked by a spill with an armful of Christmas presents. Nora arrives in the bar and Nick orders her a martini. She asks how many he’s had. Six. When her drink arrives, she tells the bartender to bring five more to catch up.

Nick and Nora’s blissful union is a rarity for onscreen marriages, even more so upon the film’s release in 1934, just two years after the end of Prohibition. Cinemas were filled with morality tales, further restricted by the recently established Production Code. But Nick and Nora’s penchant for drink isn’t represented as a kink in their marriage or a grand social problem; rather, it’s a social lubricant that greases the film’s funniest lines. A reporter asks Nick about the murder mystery: “Can’t you tell us anything about the case?” and Nick replies, “Yes, it’s putting me way behind in my drinking.” Alcohol fuels their carefree party lifestyle, sustained by Nora’s moneyed background and Nick’s plan to live happily off his wife’s bank account. None of the usual insecurities apply—he’s comfortable with the fact that his wife’s the breadwinner, and her only complaint might be that her husband is less exciting when he’s not serving as a private detective. To be sure, whenever Nick goes out sleuthing to investigate a clue, he’s always accompanied by Asta, while Nora embraces her own spirit of adventure and snoops along. Although, we get the impression that if Nick chose to be a jobless layabout, Nora wouldn’t mind that either. And that Nick and Nora also happen to be two young and attractive people with a healthy sex life, as confirmed in their lovable interactions and not-so-subtle intimations made throughout the film, speaks to the uniqueness of this cinematic couple.

The Thin Man was based on the novel of the same name by Dashiell Hammett, an author best known for hard-boiled crime fiction such as Red Harvest and The Maltese Falcon. Hammett’s book The Thin Man was first published in Redbook in 1934, and the setup about a married couple solving crimes was relatively original. By this time, Agatha Christie had written the first entries in a five-book series spanning her career about Tommy and Tuppence, a husband-and-wife duo of crime solvers (beginning with The Secret Adversary in 1922 and ending with Postern of Fate in 1973), but Christie’s characters had little of the humor found in The Thin Man films or even in Hammett’s novel. MGM purchased the film rights to Hammett’s book given his popularity, and studio director W.S. Van Dyke, who dabbled in crime fiction himself, wanted to adapt the story into a comedy unlike any other released at the time. Van Dyke sought out studio head Louis B. Mayer and asked that he be allowed to direct. Mayer saw the prospect as nothing more than a quick B-movie, and Van Dyke had already proven he could shoot cheap and fast, so why not? Yet, it was a passion project for Van Dyke, who had a vision about the production and who should play Nick and Nora Charles. Van Dyke had just finished making Manhattan Melodrama with star Clark Gable, a picture about two boyhood friends who take different paths: Gable’s character becomes a gangster, while Powell becomes District Attorney. The film would become a huge success both financially and for its stars, less for Gable and more for the apparent chemistry between supporting players Powell and Loy. Van Dyke wanted them for the roles of Nick and Nora Charles, and though Loy was on contract with MGM, Van Dyke had to convince Warner Bros. to loan out Powell.

The Thin Man was based on the novel of the same name by Dashiell Hammett, an author best known for hard-boiled crime fiction such as Red Harvest and The Maltese Falcon. Hammett’s book The Thin Man was first published in Redbook in 1934, and the setup about a married couple solving crimes was relatively original. By this time, Agatha Christie had written the first entries in a five-book series spanning her career about Tommy and Tuppence, a husband-and-wife duo of crime solvers (beginning with The Secret Adversary in 1922 and ending with Postern of Fate in 1973), but Christie’s characters had little of the humor found in The Thin Man films or even in Hammett’s novel. MGM purchased the film rights to Hammett’s book given his popularity, and studio director W.S. Van Dyke, who dabbled in crime fiction himself, wanted to adapt the story into a comedy unlike any other released at the time. Van Dyke sought out studio head Louis B. Mayer and asked that he be allowed to direct. Mayer saw the prospect as nothing more than a quick B-movie, and Van Dyke had already proven he could shoot cheap and fast, so why not? Yet, it was a passion project for Van Dyke, who had a vision about the production and who should play Nick and Nora Charles. Van Dyke had just finished making Manhattan Melodrama with star Clark Gable, a picture about two boyhood friends who take different paths: Gable’s character becomes a gangster, while Powell becomes District Attorney. The film would become a huge success both financially and for its stars, less for Gable and more for the apparent chemistry between supporting players Powell and Loy. Van Dyke wanted them for the roles of Nick and Nora Charles, and though Loy was on contract with MGM, Van Dyke had to convince Warner Bros. to loan out Powell.

William Powell was the archetypal “man about town” of 1930s Hollywood, his comic timing and sophisticated airs second to none. Born in 1892 in Pennsylvania, Powell’s interest in acting began with high school plays, which later drove him to attend New York’s American Academy of Dramatic Arts (alongside classmate Edward G. Robinson). After graduating and appearing on Broadway several times, Powell was cast in his first film role for Samuel Goldwyn’s Sherlock Holmes in 1922, playing a villainous assistant to Dr. Moriarty. His smooth good looks, refined mannerisms, and cultivated voice earned him attention from studios and maintained his career from the Silent Era into the birth of Talkies. Among his early films was a series for Paramount based on S.S. Van Dine’s detective Philo Vance. Powell made five Philo Vance films in all, beginning with The Canary Murder Case (1929) and ending with The Kennel Murder Case (1933). He also shared a memorable on-screen partnership over six pictures alongside Kay Francis, mostly in dramatic romances. But Powell truly came into his own alongside Myrna Loy, starting in Manhattan Melodrama and continuing for a total of fourteen films together. And with the success following their pairing on The Thin Man—a natural fit for Powell, having acted in detective films before—Powell went on to an illustrious career with titles like My Man Godfrey and Libeled Lady (both in 1936). He was a most genial actor, often described by his costars as a “gentleman” and a decent fellow, his wit and suave behavior not merely restricted to the written page. After retiring from acting in 1955, he lived a private life with his wife Diana Lewis until his death from old age in 1984.

Before Myrna Loy’s Nora Charles was called the “perfect wife” by critics, Loy was born in 1905 and grew up in a progressive, socially active Montana home. Her family eventually moved to California where she developed an interest in dancing. She took a job as a dancer at Grauman’s Chinese Theater in Hollywood where Rudolph Valentino saw her in a photograph and noted her beauty. Valentino suggested her for a bit role in What Price Beauty? (1925), and she continued with small parts in various unmemorable titles. By 1932, she had appeared in a staggering sixty films, largely unremarkable roles as exotic sexpots and vamps of various ethnicities. Her breakthrough came in 1930 when she met Van Dyke on the set of her pre-Code romance Penthouse; the director cast her again in The Prizefighter and the Lady (1933), Men in White (1934), and finally Manhattan Melodrama. Loy’s “American girl” allure would incite Van Dyke to cast her as Nora Charles, Nick’s well-to-do wife fascinated by the thrill of her husband chasing down a mystery. Meanwhile, as World War II geared up, Loy solidified her status as a humanitarian when she volunteered for the Red Cross and later for the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. She was also actively involved in politics, supporting FDR and the civil rights movement, and opposing HUAC. She continued to act over the next several decades, appearing in memorable roles that transcended her Thin Man typecasting, such as Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House (1948), Cheaper by the Dozen (1950), and the television drama Summer Solstice (1981) alongside Henry Fonda. Two years after receiving an honorary Academy Award in 1991, she died at the age of 88 and was epitomized by many as the iconic Nora Charles.

Before Myrna Loy’s Nora Charles was called the “perfect wife” by critics, Loy was born in 1905 and grew up in a progressive, socially active Montana home. Her family eventually moved to California where she developed an interest in dancing. She took a job as a dancer at Grauman’s Chinese Theater in Hollywood where Rudolph Valentino saw her in a photograph and noted her beauty. Valentino suggested her for a bit role in What Price Beauty? (1925), and she continued with small parts in various unmemorable titles. By 1932, she had appeared in a staggering sixty films, largely unremarkable roles as exotic sexpots and vamps of various ethnicities. Her breakthrough came in 1930 when she met Van Dyke on the set of her pre-Code romance Penthouse; the director cast her again in The Prizefighter and the Lady (1933), Men in White (1934), and finally Manhattan Melodrama. Loy’s “American girl” allure would incite Van Dyke to cast her as Nora Charles, Nick’s well-to-do wife fascinated by the thrill of her husband chasing down a mystery. Meanwhile, as World War II geared up, Loy solidified her status as a humanitarian when she volunteered for the Red Cross and later for the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. She was also actively involved in politics, supporting FDR and the civil rights movement, and opposing HUAC. She continued to act over the next several decades, appearing in memorable roles that transcended her Thin Man typecasting, such as Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House (1948), Cheaper by the Dozen (1950), and the television drama Summer Solstice (1981) alongside Henry Fonda. Two years after receiving an honorary Academy Award in 1991, she died at the age of 88 and was epitomized by many as the iconic Nora Charles.

The Thin Man was filmed on the MGM lot in a mere fourteen days (with a few extra days allotted for reshoots), thanks in large part to Van Dyke, better known in Hollywood circles as “One Take” Woody. As a studio director, he helmed a number of popular titles such as Tarzan the Ape Man (1932) and San Francisco (1936), his talent ranging across virtually every genre. Van Dyke’s fast-paced approach stemmed from his belief that actors were at their freshest, most un-self-conscious, instinctual and believable best on their first take. He described his approach as follows: “I finish the picture nice and fast. No fooling around. Print take one. I finish three or four days ahead of schedule and they give me a bonus. Then I go back (with retakes and editing) and really make my picture.” What’s more, he would ask his performers to rehearse a scene on set, and then unbeknownst to them, Van Dyke would motion to the camera operator to roll camera and capture the rehearsal. As a result, The Thin Man and other films by Van Dyke have an almost impulsive quality to them, yet without sacrificing the film’s overall polish. Not for a moment does The Thin Man look as though it was filmed in just a couple short weeks. Perhaps this is due to cinematographer James Wong Howe, one of the premier cameramen working in Hollywood, who would go on to shoot such visually distinct pictures as Sweet Smell of Success (1957) and Seconds (1966). But maybe everything about The Thin Man just seems more polished because of the sophisticated and lighthearted nature of Nick and Nora’s marriage—itself perhaps the film’s greatest achievement.

Samuel Marx, head of MGM’s story department, observed, “In those days you got married at the end of the movie, not at the beginning. Marriage wasn’t supposed to be fun.” Together, Powell and Loy make marriage look like a picnic. Their chemistry makes it impossible to imagine anyone else playing Nick and Nora, Powell with his dry wit and Loy with her affectionate frowns. Never before had a married couple seemed to enjoy all facets of married life with such resounding ease. Nick wants only to retire and spend his wife’s money; Nora wants excitement out of her husband’s detective cases. As a couple, they orbit around one another, complimenting the other’s needs by remaining spontaneous and filled with an undeniable joviality. Indeed, this is an unconventional pair. Consider their Christmas morning. Nora has purchased her husband an air rifle of all things; he lies on the couch, popping balloons with trick shots between his legs and behind his back. Nick got his wife a fur coat, and she remains wrapped in it, despite it being “stifling” in their warm apartment. Their idiosyncratic partnership seems to thrive on each other’s unusual behavior, but in spite of their seemingly impossible eccentricities, the actors make every line feel natural, every oddball gesture either improvised or unforced by the amiable acting duo. Moreover, Nick and Nora borrow a few beats from real-life counterparts; to adapt Hammett’s book, Van Dyke’s producer Hunt Stromberg purposefully sought out the famously quirky husband-and-wife screenwriting team of Albert Hackett and Frances Goodrich, who would go on to write such knowing comedies about relationships as Father of the Bride (1950) and Seven Brides for Seven Brothers (1954). The writing duo is widely believed to have injected themselves into Nick and Nora, whereas Hammett would later insist that he wrote Nick based on himself and Nora based on his lover Lillian Hellman.

Samuel Marx, head of MGM’s story department, observed, “In those days you got married at the end of the movie, not at the beginning. Marriage wasn’t supposed to be fun.” Together, Powell and Loy make marriage look like a picnic. Their chemistry makes it impossible to imagine anyone else playing Nick and Nora, Powell with his dry wit and Loy with her affectionate frowns. Never before had a married couple seemed to enjoy all facets of married life with such resounding ease. Nick wants only to retire and spend his wife’s money; Nora wants excitement out of her husband’s detective cases. As a couple, they orbit around one another, complimenting the other’s needs by remaining spontaneous and filled with an undeniable joviality. Indeed, this is an unconventional pair. Consider their Christmas morning. Nora has purchased her husband an air rifle of all things; he lies on the couch, popping balloons with trick shots between his legs and behind his back. Nick got his wife a fur coat, and she remains wrapped in it, despite it being “stifling” in their warm apartment. Their idiosyncratic partnership seems to thrive on each other’s unusual behavior, but in spite of their seemingly impossible eccentricities, the actors make every line feel natural, every oddball gesture either improvised or unforced by the amiable acting duo. Moreover, Nick and Nora borrow a few beats from real-life counterparts; to adapt Hammett’s book, Van Dyke’s producer Hunt Stromberg purposefully sought out the famously quirky husband-and-wife screenwriting team of Albert Hackett and Frances Goodrich, who would go on to write such knowing comedies about relationships as Father of the Bride (1950) and Seven Brides for Seven Brothers (1954). The writing duo is widely believed to have injected themselves into Nick and Nora, whereas Hammett would later insist that he wrote Nick based on himself and Nora based on his lover Lillian Hellman.

The thin man of the title is not Nick Charles, as audiences would later associate, but rather inventor Clyde Wynant (Edward Ellis), a gaunt and irritable man who goes missing. In the film’s prologue, Wynant’s daughter Dorothy (Maureen O’Sullican) visits him with her fiancé Tommy (Henry Wadsworth) to announce their engagement, except the old man may not be able to attend. He’ll be away on secret research and his attorney MacCaulay (Porter Hall), who just arrives as Dorothy and Tommy are leaving, sends Wynant off with $1,000 in cash to a destination not even MacCaulay knows. The night before Wynant is set to leave, he stops at his office to put $50,000 in bonds, an intended wedding present for Dorothy, in his safe, and all the time his accountant Tanner (Cyril Thornton) is watching. The next day the bonds are missing. Wynant is quick to accuse Tanner, but Tanner suggests perhaps Wynant’s mistress Julia (Natalie Moorhead) stole them along with her shady boyfriend Morelli (Edward Brophy), or maybe it was Julia’s other beau, the scar-faced crook Nunheim (Harold Huber). Before long, the audience isn’t asking where the bonds have disappeared to, but rather where Wynant has gone—he’s disappeared. Now inside a posh night club, Dorothy laments to her fiancé that her father is missing. Just then, Dorothy spies Nick Charles, a family acquaintance, standing at the night club’s bar and asks him to investigate her predicament. Nick explains that he’s no longer a detective and assures Dorothy that her father is probably just working intently. Later, Nora insists Nick should take the case because she finds it thrilling, and also because it’s the nice thing to do. Of course, Wynant is found dead, and Nick must scrutinize the suspects. The investigation comes to a head when, in standard mystery fashion, Nick invites all suspected parties over for dinner and talks his way through exposing the killer.

When writers Goodrich and Hackett first expressed concerns to Van Dyke that they had never written a mystery before, Van Dyke waved off their apprehensions. “I don’t care anything about the mystery stuff,” he told them, “just give me five scenes between Nick and Nora.” Although the writing duo ultimately thought little of their own script, the witticisms they poured into the dialogue, compounded by the draw of Powell and Loy, would ultimately earn them an Academy Award nomination for their screenplay. Rife with double-entendres and sly quips, The Thin Man contains countless memorable lines. At the Charles’ dinner populated with shady types and a suspected killer, Nora asks the waiter, “Will you serve the nuts—I mean, will you serve the guests the nuts?” Some of these lines pushed the Production Code’s limits and were deemed “censorable” but were allowed nevertheless. Theater owners complained about the implications of Loy’s line “What’s that man doing in my drawers?” when she finds someone ransacking her dresser, while others questioned the film’s excessive drinking. Yet, such hilarious exchanges between Powell and Loy solidify their almost adolescent playfulness with one another. After confronting an armed man in their apartment, they read about the encounter in the paper the next morning. “I was shot twice in the Tribune,” Nick brags. “I read you were shot five times in the tabloids,” Nora observes. “It’s not true,” says Nick, “he didn’t come anywhere near my tabloids.”

When writers Goodrich and Hackett first expressed concerns to Van Dyke that they had never written a mystery before, Van Dyke waved off their apprehensions. “I don’t care anything about the mystery stuff,” he told them, “just give me five scenes between Nick and Nora.” Although the writing duo ultimately thought little of their own script, the witticisms they poured into the dialogue, compounded by the draw of Powell and Loy, would ultimately earn them an Academy Award nomination for their screenplay. Rife with double-entendres and sly quips, The Thin Man contains countless memorable lines. At the Charles’ dinner populated with shady types and a suspected killer, Nora asks the waiter, “Will you serve the nuts—I mean, will you serve the guests the nuts?” Some of these lines pushed the Production Code’s limits and were deemed “censorable” but were allowed nevertheless. Theater owners complained about the implications of Loy’s line “What’s that man doing in my drawers?” when she finds someone ransacking her dresser, while others questioned the film’s excessive drinking. Yet, such hilarious exchanges between Powell and Loy solidify their almost adolescent playfulness with one another. After confronting an armed man in their apartment, they read about the encounter in the paper the next morning. “I was shot twice in the Tribune,” Nick brags. “I read you were shot five times in the tabloids,” Nora observes. “It’s not true,” says Nick, “he didn’t come anywhere near my tabloids.”

More than just dialogue, The Thin Man also contains a sizeable amount of pure physical comedy, with Loy’s pratfall entrance and Powell’s air rifle routine being the prime examples already discussed. Much of the physical comedy is centered around Asta, however. Watch the scene on the city street where Nick and Lt. Guild (Nat Pendleton) prattle on about the case, while Nora walks Asta and listens, her arm in Nick’s. The shot cuts off just below the actors’ waists, and we see only the leash in Nora’s hand but not Asta. As the group moves along, Nora’s arm is extended out in front of her with Asta leading, and as they continue to walk her arm is drawn behind her—Asta has stopped below the frame to smell something (be it a light post or fire hydrant). With Nora’s arm in Nick’s, he stops too. Lt. Guild halts as well. All of it on account of Asta. The audience is so busy laughing at this subtle visual gag that we hardly notice the details of the case unfold in the dialogue. Other animal reaction shots and Asta’s generally cowardly behavior (Asta emerges from under the bed, where he was hiding during some gunplay, and Nick remarks, “You’re a fine watchdog…”) are handled with a light touch, and Asta’s presence becomes essential to the chemistry between Nick and Nora. Asta was played by a Wire-Haired Fox Terrier named Skippy who helped popularize the breed with American pet owners for the next decade or more. Skippy became so popular that he was earning $200 a week, more even than his trainer. He would go on to star in other doggie roles outside of the Thin Man series in The Awful Truth (1937) and Bringing Up Baby (1938), both alongside Cary Grant.

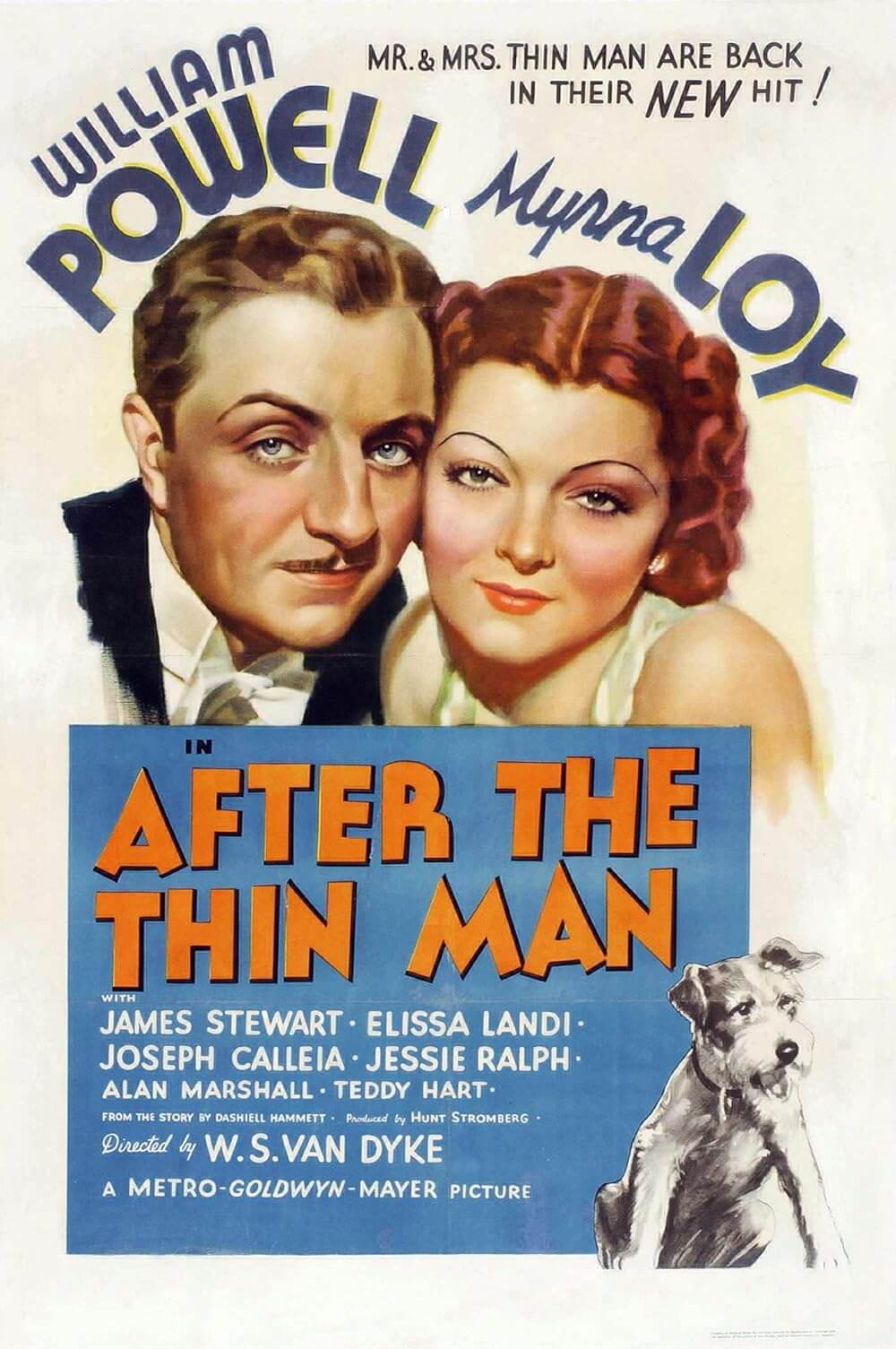

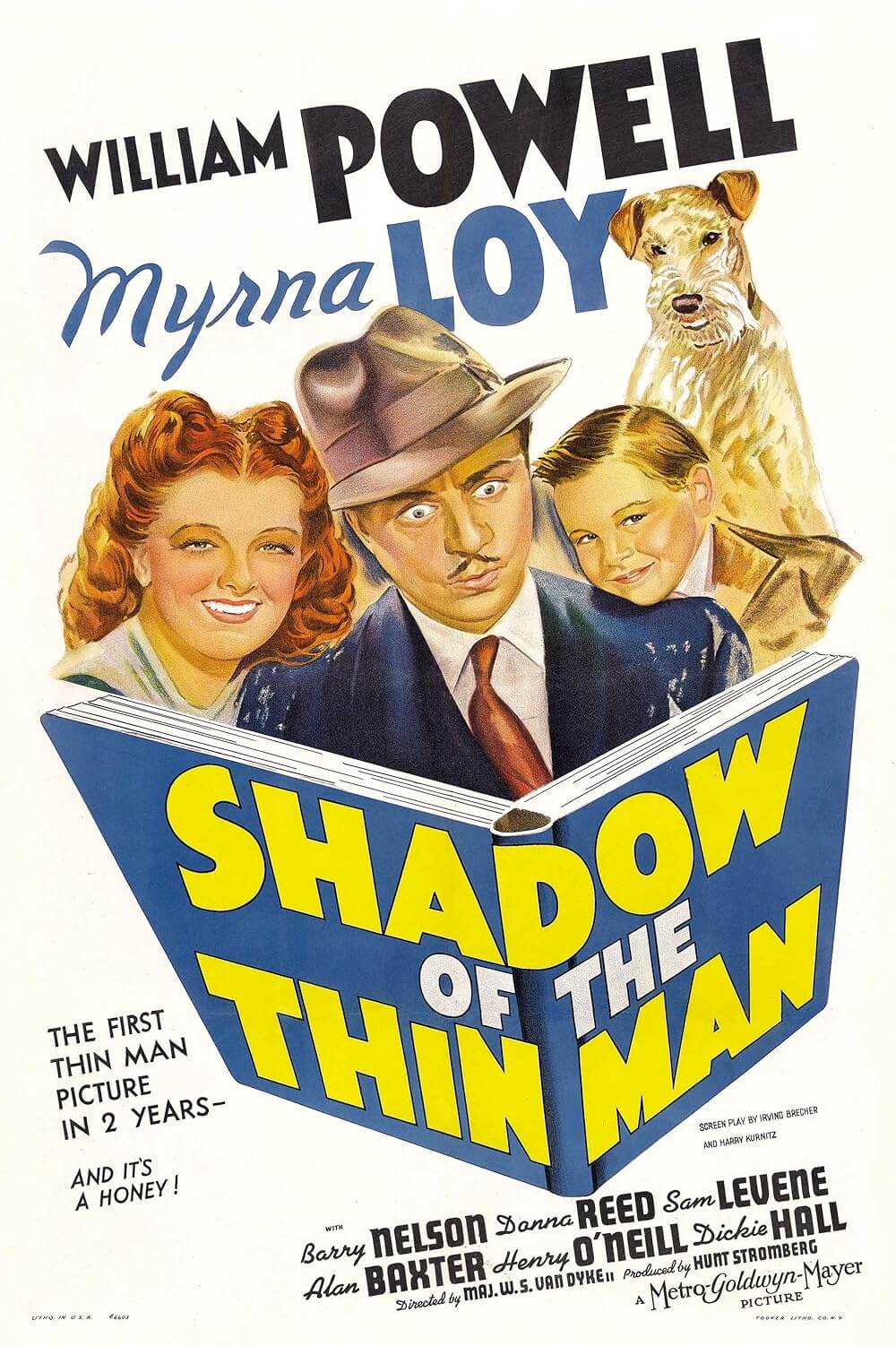

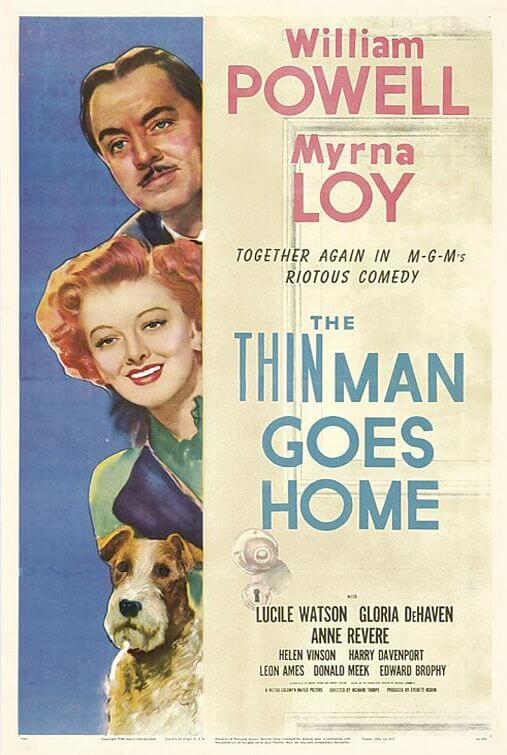

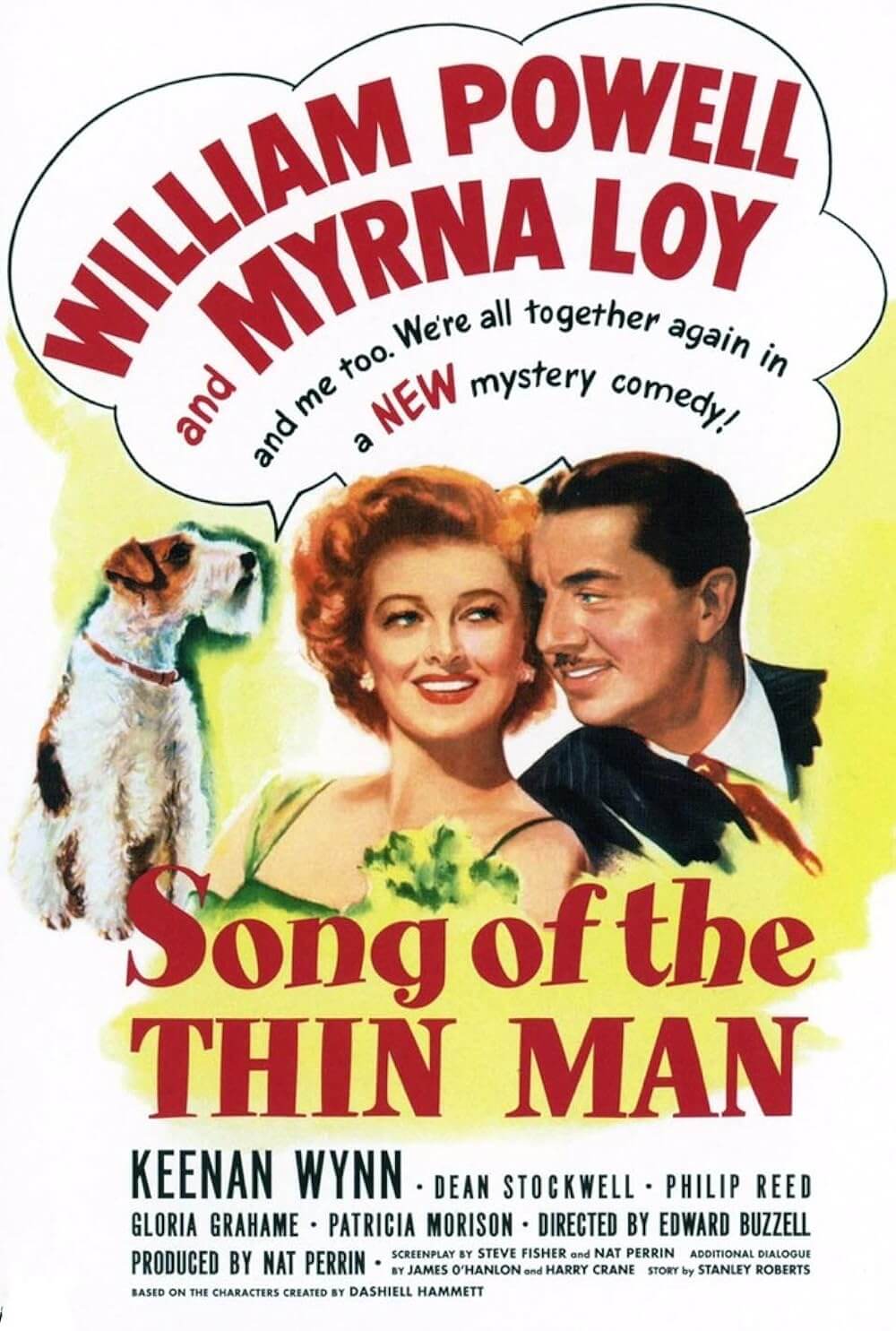

Released in May of 1934, The Thin Man became a huge hit for MGM, earning upwards of $2 million for a production that cost less than $500,000 to make. By September of that year, MGM announced plans for a sequel. In fact, The Thin Man spawned five sequels, many of them very good, all of them at least entertaining because of the presence of Nick and Nora. And, of course, Asta, who is used to more comic effect in the subsequent films. Van Dyke directed three of them: After the Thin Man (1936), Another Thin Man (1939), and Shadow of the Thin Man (1941), while two more were produced after Van Dyke’s death in 1943, including The Thin Man Goes Home (1945, directed by Richard Thorpe) and Song of the Thin Man (1947, directed by Edward Buzzell). The original and its sequels have been immeasurably influential, resulting in a number of poor offshoots, but never has another motion picture captured the same sophistication innate to The Thin Man series. MGM tried to reformulate the series in Fast Company (1938) and Fast and Loose in 1939, about a rare bookseller and his wife who solve cases about missing books from private collections. Television boasted a few similarly themed shows, notably McMillan & Wife (1971-1977) with Rock Hudson and Susan Saint James, and Hart to Hart (1979–1984) with Robert Wagner and Stefanie Powers. Powell even starred in a few comparable setups with Star of Midnight (1935) opposite Ginger Rogers and The Ex-Mrs. Bradford (1936) alongside Jean Arthur.

Released in May of 1934, The Thin Man became a huge hit for MGM, earning upwards of $2 million for a production that cost less than $500,000 to make. By September of that year, MGM announced plans for a sequel. In fact, The Thin Man spawned five sequels, many of them very good, all of them at least entertaining because of the presence of Nick and Nora. And, of course, Asta, who is used to more comic effect in the subsequent films. Van Dyke directed three of them: After the Thin Man (1936), Another Thin Man (1939), and Shadow of the Thin Man (1941), while two more were produced after Van Dyke’s death in 1943, including The Thin Man Goes Home (1945, directed by Richard Thorpe) and Song of the Thin Man (1947, directed by Edward Buzzell). The original and its sequels have been immeasurably influential, resulting in a number of poor offshoots, but never has another motion picture captured the same sophistication innate to The Thin Man series. MGM tried to reformulate the series in Fast Company (1938) and Fast and Loose in 1939, about a rare bookseller and his wife who solve cases about missing books from private collections. Television boasted a few similarly themed shows, notably McMillan & Wife (1971-1977) with Rock Hudson and Susan Saint James, and Hart to Hart (1979–1984) with Robert Wagner and Stefanie Powers. Powell even starred in a few comparable setups with Star of Midnight (1935) opposite Ginger Rogers and The Ex-Mrs. Bradford (1936) alongside Jean Arthur.

Indeed, any crime-solving married couple from now until the end of cinema will have found its roots in Nick and Nora Charles. Before The Thin Man, a funny detective film had never been conceived; injecting screwball humor into a hard-boiled murder mystery was a genre amalgamation that worried everyone at MGM, except of course Van Dyke. But the studio’s gamble on the “fun with murder” concept was the perfect escapism for Depression-era audiences who could lose themselves in Nick and Nora’s graceful conversations, which, despite the stakes of the murder mystery, carry on as if they haven’t a care in the world. Modern detective stories feel saturated by gritty realism, but The Thin Man embraces a merry domesticity that delivers just the right balance of fantasy and naturalism inside its touches of danger. Along with the idyllic and delightfully untroubled relationship between the wisecracking Nick and Nora, how could audiences not fall in love with the effortless class and enchanting nature of the storytelling? And how could they not admire and aspire to shape their own marriage after Nick and Nora’s? More than just a time capsule representing how it was the right film at the right time, a landmark of cinema’s most enchanting and sophisticated era, today The Thin Man remains an unparalleled mixture of laughs and suspense that many have imitated but none have equaled, and whose charm shows no signs of wear.

Bibliography:

Behlmer, Rudy (editor). W.S. Van Dyke’s Journal. The Scarecrow Press, 1996.

Bryant, Roger. William Powell: The Life and Films. McFarland & Company, 2006.

Francisco, Charles. Gentleman: The William Powell Story. St. Martin’s Press, 1985.

Goodrich, David L. The Real Nick and Nora. Southern Illinois University Press, 2001.

Johnson, Diane. Dashiell Hammett: A Life. Random House, 1983.

Loy, Myrna (with James Kostsilibas-Davis). Being and Becoming. Alfred A. Knopf, 1987.

Tranberg, Charles. The Thin Man Films: Murder Over Cocktails. BearManor Media, 2008.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review