The Definitives

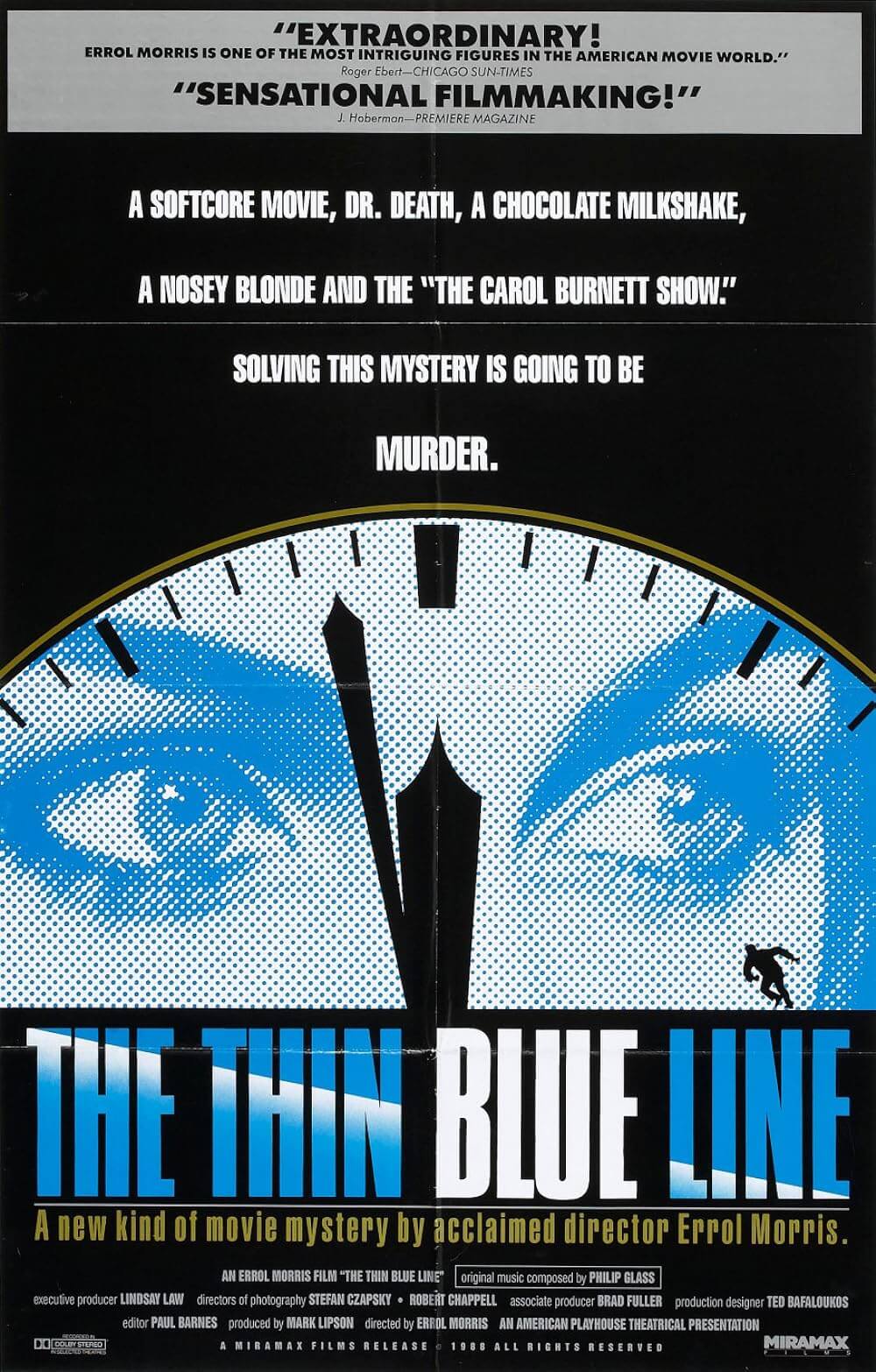

The Thin Blue Line (1988)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

In The Thin Blue Line, director Errol Morris investigates the wrongful conviction of Texan Randall Adams, who, in place of a more obvious suspect, was arrested for killing a police officer. Upon its release in 1988, audiences had never seen anything like its use of point-counterpoint interviews, Philip Glass’ haunting score, or atmospheric reenactments in a documentary. Morris’ unique treatment famously provided evidence controverting witness testimony in the case, which led to Adams’ conviction being overturned in 1989. Morris’ work would go on to earn honors abound and was called the Best Documentary by several critical associations, including the National Board of Review, the National Society of Film Critics, and many others. More recently in 2014, the British Film Institute’s magazine Sight and Sound polled critics about the best documentaries ever made, and The Thin Blue Line earned fifth place. At the same time, other groups question whether the film is a documentary at all. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences refused to grant it an Oscar nomination for its use of several reenactments and stylization throughout. Indeed, Morris’ film does not strictly fit any definition for a documentary, leaving only segments of the fanatically detailed and multifaceted film worthy of the documentary classification, while other segments should be called something else entirely. What that “something else” is proved elusive and indefinable, in large part because the film remains unique to motion pictures, nonfiction or otherwise.

Nevertheless, The Thin Blue Line has been widely praised as one of the greatest of all documentaries. But before examining the film in any detail, the documentary itself demands some clarification. Documentaries raise a lot of questions. Not merely about their subject matter but also about whether documentaries should be considered nonfiction, a subset of nonfiction, or their own category altogether. Do documentaries explore untold facts with journalistic integrity and impartiality, or do they seek something less tangible, like personal truth? How do they investigate, observe, represent, or expose, and are their methods inherently objective or subjective? Perhaps more importantly, are audiences asking these questions when watching a documentary, or do they merely consume the message without a second thought? When most viewers think of a documentary, they think of factual accounts on film. But there are no rules to documentary filmmaking, no established standard. There are no ethics committees or fact-checkers prohibiting documentarians from spinning their subjects with sensationalist perspectives or protecting viewers from the potential biases of the filmmaker. Author and professor Carl Plantinga described his characterization of the documentary in his paper “What a Documentary Is, After All,” published in the pages of The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism in 2005. While Plantinga concedes that any fixed definition for a documentary remains highly debated due to the nebulous form documentaries can sometimes take, he outlines several techniques that, when combined through nonfiction filmmaking, create a documentary.

Plantinga argues a few points that suggest documentaries, in their most conventional and commonly understood form, are a class of nonfiction filmmaking that present their stories in, traditionally, two ways: Either they create an index of the chosen subject matter through trace evidence, such as photographs, sound recordings, or testimonies that explore the world; or, documentaries involve a filmmaker declaring something about a subject and then proceeding to reinforce and reveal the actuality of their assertion through the course of a filmic essay. The indexical form of documentaries is most often associated with the cinéma vérité movement that began in 1960. For many film scholars, cinéma vérité titles like Robert Drew’s Primary (1960) or Chris Hegedus and D. A. Pennebaker’s The War Room (1993) embrace an ideal observational style, which is deemed preferable as it does not interact with its subjects and simply bears silent witness. The alternative is an assertive and more popish style of documentary used by filmmakers like Michael Moore or Morgan Spurlock, who declare their film’s intent and then seek to edify and convince their audience, often in an entertaining way. And while Plantinga admits that these two definitions, which are streamlined to their basic terms here, are not all-encompassing, he concedes they remain too restrictive of many of today’s documentaries. Ultimately, Plantinga offers a less restrictive definition of documentaries that he calls “asserted veridical representation”—meaning, films that assert their purpose, use relevant and reliable images and sounds to form the argument, and may even use staged approximations of actual events.

Plantinga argues a few points that suggest documentaries, in their most conventional and commonly understood form, are a class of nonfiction filmmaking that present their stories in, traditionally, two ways: Either they create an index of the chosen subject matter through trace evidence, such as photographs, sound recordings, or testimonies that explore the world; or, documentaries involve a filmmaker declaring something about a subject and then proceeding to reinforce and reveal the actuality of their assertion through the course of a filmic essay. The indexical form of documentaries is most often associated with the cinéma vérité movement that began in 1960. For many film scholars, cinéma vérité titles like Robert Drew’s Primary (1960) or Chris Hegedus and D. A. Pennebaker’s The War Room (1993) embrace an ideal observational style, which is deemed preferable as it does not interact with its subjects and simply bears silent witness. The alternative is an assertive and more popish style of documentary used by filmmakers like Michael Moore or Morgan Spurlock, who declare their film’s intent and then seek to edify and convince their audience, often in an entertaining way. And while Plantinga admits that these two definitions, which are streamlined to their basic terms here, are not all-encompassing, he concedes they remain too restrictive of many of today’s documentaries. Ultimately, Plantinga offers a less restrictive definition of documentaries that he calls “asserted veridical representation”—meaning, films that assert their purpose, use relevant and reliable images and sounds to form the argument, and may even use staged approximations of actual events.

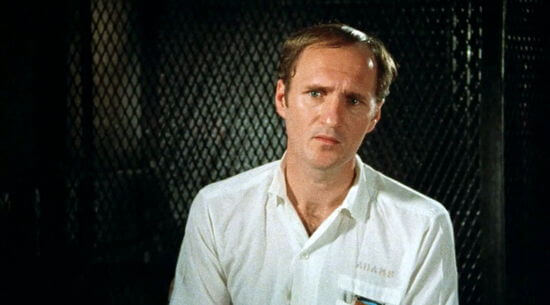

Explaining the conventional scholarly definitions for documentaries above as I have is meant to create a platform against which The Thin Blue Line should be measured. To be sure, Morris’ film stands on the periphery of any definition for the documentary, challenging what it means to be a documentary. In traditional terms, Morris’ film includes interviews that tell the story of Dallas police officer Robert Wood, who, during a routine traffic stop in 1976, was shot multiple times and killed on the roadside. The interviews also involve the arrest and conviction of the wrong man, Randall Adams, and how investigators ignored evidence that should have led them to David Harris, a minor who would elude the death penalty if convicted. Two sides of the story materialize through various personal accounts, which are not observations of reality but rather examples of the shifting, opposing perspectives of those interviewed. Morris explores alternate narratives through these interviews, using them to gradually reveal the film’s inevitable assertion of Adams’ innocence and Harris’ guilt—an assertion not stated outright but determined by the viewer. Occasional close-up cutaways to newspaper clippings, courtroom sketches, or redacted police reports also provide trace evidence to reinforce the testimony of Morris’ interview subjects. But then, Morris also includes several highly stylized reenactments of witness testimony—and the footage, shot with all the expressive flourishes of a neo-noir, appears regardless of whether that testimony proves to be false or misremembered. In fact, Morris often juxtaposes the reenactments of what are either lies or misremembered truths against the more reliable testimony from his interviewees. All the while, the director never appears in the film; though, his voice can be heard in the final scenes.

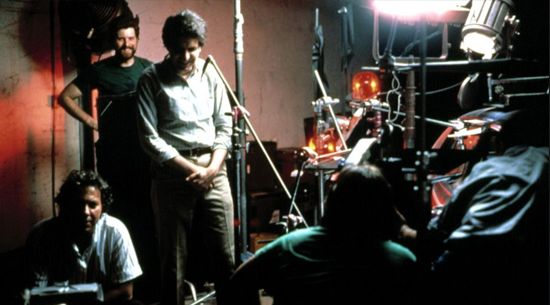

A force of unorthodoxy, Morris, born in 1948, found himself resistant to the formalism of graduate school in the early 1970s and, though he studied the history of physics at Princeton and philosophy at Berkeley, he grew impatient with the customs of scholarly education. His passion for cinema, film noir most of all, solidified at the Pacific Film Archive on the Berkeley campus under its director, Tom Luddy. Morris soon wanted to make his own films. He connected with Werner Herzog for a planned project about Wisconsin serial killer Ed Gein that fell through after several false starts. Eventually, Herzog provided Morris with a modest backing to complete his first documentary, and the German maverick promised to eat his shoe if Morris ever completed it. Morris headed to Vernon, Florida, to make a film about its citizens called “Nub City,” concerning a bizarre trend in which people intentionally removed limbs to collect large insurance payouts. After receiving threats from the people of Vernon if he exposed their scam, Morris found himself conveniently interested in a San Francisco story about pet cemeteries, resulting in his renowned 1978 debut, Gates of Heaven. He later returned to Vernon and shot Vernon, Florida (1981), although the film contains no mention of the personal injury scam. And, of course, Herzog famously kept his promise to Morris, as documented by Les Blank in the 1980 short Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe.

A force of unorthodoxy, Morris, born in 1948, found himself resistant to the formalism of graduate school in the early 1970s and, though he studied the history of physics at Princeton and philosophy at Berkeley, he grew impatient with the customs of scholarly education. His passion for cinema, film noir most of all, solidified at the Pacific Film Archive on the Berkeley campus under its director, Tom Luddy. Morris soon wanted to make his own films. He connected with Werner Herzog for a planned project about Wisconsin serial killer Ed Gein that fell through after several false starts. Eventually, Herzog provided Morris with a modest backing to complete his first documentary, and the German maverick promised to eat his shoe if Morris ever completed it. Morris headed to Vernon, Florida, to make a film about its citizens called “Nub City,” concerning a bizarre trend in which people intentionally removed limbs to collect large insurance payouts. After receiving threats from the people of Vernon if he exposed their scam, Morris found himself conveniently interested in a San Francisco story about pet cemeteries, resulting in his renowned 1978 debut, Gates of Heaven. He later returned to Vernon and shot Vernon, Florida (1981), although the film contains no mention of the personal injury scam. And, of course, Herzog famously kept his promise to Morris, as documented by Les Blank in the 1980 short Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe.

Morris received funding for a third film that was intended to investigate Dr. James Grigson, a psychiatrist for Texas prosecutors nicknamed “Dr. Death,” as Dr. Grigson gave unwavering testimony in more than 100 death penalty trials. Texas law requires a professional opinion that the defendant will commit similar crimes in the future before a death penalty sentence is reached, and Dr. Grigson made such predictions by the dozens. Morris told an interviewer, “I am profoundly skeptical about our abilities to predict the future in general, and human behavior in particular, except—and I have to make an exception here—except what Dr. Death will say in the penalty phase of a capital murder trial.” Convinced that Dr. Grigson would always testify, with absolute certainty, for the death penalty no matter the circumstances or defendant’s case, Morris began to interview death row inmates that Dr. Death helped sentence. Along the way, he met Adams and became fascinated by the inmate’s melancholy manner and story, as Adams seemed resigned to believe that no one was listening to his claims of innocence. Setting aside his initial story about Dr. Death, Morris began a three-year investigation into Adams that ended with the release of The Thin Blue Line. Before long, sections of the film were used in an appeal to prove certain witness testimonies to be false, resulting in Adams’ vindication.

Morris’ film contains none of the fly-on-a-wall tactics of a cinéma vérité documentary—not even natural lighting or really-there handheld camerawork. His film consists of mostly interviews conducted with a stationary camera mounted on a tripod and great care put into the aesthetic exhibition. The interviews are presented in a confessional approach, as Morris remains off-camera for the entirety. As the interviewees give their accounts of what happened, the viewer rarely hears the filmmaker’s voice asking what must be open-ended questions, which allow his interviewees to speak and reveal themselves. Meanwhile, Morris resists stating outright whether this or that interviewee is giving a true account; he requires the audience to read between his subjects’ remarks to discover the truth. Given his lack of onscreen presence, any notion of his intervention in the interview process seems unapparent and, therefore, the audience feels engaged as a participating investigator in a mystery. And yet, Morris methodically shapes and presents the film’s interview segments in several strategic ways to guide the audience’s beliefs, and ultimately our judgment of Harris and exoneration of Adams. Because he adopts an open, seemingly lesser-directed interview style, the objective of The Thin Blue Line does not seem forced and contains an absolute truth the audience discovers for themselves. However, the film has been carefully designed to function in this way.

Morris’ film contains none of the fly-on-a-wall tactics of a cinéma vérité documentary—not even natural lighting or really-there handheld camerawork. His film consists of mostly interviews conducted with a stationary camera mounted on a tripod and great care put into the aesthetic exhibition. The interviews are presented in a confessional approach, as Morris remains off-camera for the entirety. As the interviewees give their accounts of what happened, the viewer rarely hears the filmmaker’s voice asking what must be open-ended questions, which allow his interviewees to speak and reveal themselves. Meanwhile, Morris resists stating outright whether this or that interviewee is giving a true account; he requires the audience to read between his subjects’ remarks to discover the truth. Given his lack of onscreen presence, any notion of his intervention in the interview process seems unapparent and, therefore, the audience feels engaged as a participating investigator in a mystery. And yet, Morris methodically shapes and presents the film’s interview segments in several strategic ways to guide the audience’s beliefs, and ultimately our judgment of Harris and exoneration of Adams. Because he adopts an open, seemingly lesser-directed interview style, the objective of The Thin Blue Line does not seem forced and contains an absolute truth the audience discovers for themselves. However, the film has been carefully designed to function in this way.

Morris organizes his interviews in opposition to one another, so his subjects give conflicting accounts and leave the viewer to decide who to believe. By approaching both sides of the argument, Morris represents the larger set of circumstances. The interviewees’ remarks interact and inform one another, transforming them into characters in an unfolding drama. For example, supposed witness Emily Miller says in an interview that she enjoys “helping out” police because “I wanted to be a wife of a detective or be a detective.” Miller goes on to claim, “It’s always happening to me… There are killings, and I’m getting involved.” The interview might be taken as fact, except in the following scene, Adams’ defense attorney Edith James reveals that Miller has had dealings with the police before. Specifically, James notes that Miller had reason to make a deal and seek a reward for giving false testimony. Afterward, everything Miller says seems suspect, as though she is trying to help capture a criminal no matter the cost instead of providing an honest witness statement. The back-and-forth of Morris’ interviews turns his subjects into opposing players in a dramatic conflict. For instance, James provides no end of Southern sass in her lively and frank commentary concerning the logical gaps in the investigation and court case, and her tell-it-like-it-is style supports her convincing remarks against that of someone like Miller.

Every shot has been evocatively lit and staged with intention. As Yale film studies professor Charles Musser observed, Adams’ interviews show him in a white jumpsuit, while his backdrop appears dark, allowing Adams to radiate the color of innocence. By contrast, Harris appears in a prison garb color more commonly associated with conviction: orange, while his background has been lit by a blood-red hue. Similarly, the film’s most unreliable interview witnesses align with Harris, such as Miller in her red sweater. Much like his use of lighting and (let’s call it) costuming, viewers should take notice of the angle at which Morris directs his interviewees’ eyes in relation to the camera. Less truthful witnesses seem to divert their eyes away from the camera, whereas the seemingly more truthful subjects look almost into the lens. The result could be revealing in one of two ways: 1) Morris has a sense that his interviewee was perhaps less-than-truthful, and so he made a conscious decision to seat himself away from the camera, thus creating the correlation between the angle of their eyes to the lens and the truthfulness of their account. If this is the case, then it’s a brilliant tactic on his part, and a very subtly effective one at that. Or 2), it was not a conscious choice by Morris, and the interviewees who give falsified accounts of what happened naturally diverted their eyes from the camera (as avoidance of eye contact is often considered a liar’s tell). The trend is not always consistent since Harris and Miller seem to look at the camera closely. In the former case, it could be because he’s a psychopath and does not necessarily believe he is lying; in the latter case, she seems obsessed with attention and may feed off the camera’s gaze.

Every shot has been evocatively lit and staged with intention. As Yale film studies professor Charles Musser observed, Adams’ interviews show him in a white jumpsuit, while his backdrop appears dark, allowing Adams to radiate the color of innocence. By contrast, Harris appears in a prison garb color more commonly associated with conviction: orange, while his background has been lit by a blood-red hue. Similarly, the film’s most unreliable interview witnesses align with Harris, such as Miller in her red sweater. Much like his use of lighting and (let’s call it) costuming, viewers should take notice of the angle at which Morris directs his interviewees’ eyes in relation to the camera. Less truthful witnesses seem to divert their eyes away from the camera, whereas the seemingly more truthful subjects look almost into the lens. The result could be revealing in one of two ways: 1) Morris has a sense that his interviewee was perhaps less-than-truthful, and so he made a conscious decision to seat himself away from the camera, thus creating the correlation between the angle of their eyes to the lens and the truthfulness of their account. If this is the case, then it’s a brilliant tactic on his part, and a very subtly effective one at that. Or 2), it was not a conscious choice by Morris, and the interviewees who give falsified accounts of what happened naturally diverted their eyes from the camera (as avoidance of eye contact is often considered a liar’s tell). The trend is not always consistent since Harris and Miller seem to look at the camera closely. In the former case, it could be because he’s a psychopath and does not necessarily believe he is lying; in the latter case, she seems obsessed with attention and may feed off the camera’s gaze.

Similarly, Morris provides his own nonverbal commentary when he engages in formal mockery of those witnesses he deems unreliable, in turn accentuating the idea that certain witnesses are untrustworthy. As the majority of the film’s runtime consists of interview footage, the occasional cutaways to old movie footage or newspaper clippings stand out as the filmmaker’s voice interrupting his otherwise predominant let-the-witnesses-speak-for-themselves approach. For instance, there’s a point when James says that the two unreliable witnesses may be testifying because they are after something else (attention, money, etc.). Morris seems to confirm this with his visual voice when he cuts to a nondescript clipping with the word “Reward” stenciled across the screen. The use of a newspaper clipping in this example does not provide definitive proof of James’ suggestion—in fact, it does not prove anything at all—but rather, it delineates Morris’ stance that Miller’s testimony was tarnished by an ulterior motive.

Throughout the film, Morris resists interaction with his interviewees and, at least onscreen, does not seem to be driving the conversation to an intended conclusion. It never appears as though his subjects are responding to a leading question; rather, they are telling their version of the story or giving their impression of the people involved. Because of his use of interviews, his perspective as a filmmaker seems more authentic and true, as he permits his interviewees to tell their personal truth. This remains true until his final interview with Harris, captured on tape recorder but not on film. Morris’ voice now becomes a component in the trace evidence and interview process, as the conversation between them features Harris offering a roundabout confession by saying there is “no doubt” of Adams’ innocence “‘Cause I’m the one who knows.” The sequence shows the viewer a small handheld tape player on which Morris recorded his interview with Harris. As it includes the filmmaker’s voice in the trace evidence, it lends the film a quality of investigative journalism, or at least amateur sleuthing.

Throughout the film, Morris resists interaction with his interviewees and, at least onscreen, does not seem to be driving the conversation to an intended conclusion. It never appears as though his subjects are responding to a leading question; rather, they are telling their version of the story or giving their impression of the people involved. Because of his use of interviews, his perspective as a filmmaker seems more authentic and true, as he permits his interviewees to tell their personal truth. This remains true until his final interview with Harris, captured on tape recorder but not on film. Morris’ voice now becomes a component in the trace evidence and interview process, as the conversation between them features Harris offering a roundabout confession by saying there is “no doubt” of Adams’ innocence “‘Cause I’m the one who knows.” The sequence shows the viewer a small handheld tape player on which Morris recorded his interview with Harris. As it includes the filmmaker’s voice in the trace evidence, it lends the film a quality of investigative journalism, or at least amateur sleuthing.

Morris does not engage in an assertive documentary approach by stating a thesis at the beginning of The Thin Blue Line and then providing evidence of that thesis throughout the film. As suggested above, his assertion is construed through an assumed purpose that remains undeclared by the filmmaker. Even so, Morris’ assertion becomes apparent by the end of the film: he seeks the truth, and he intends his film to be a representation of the truth arrived upon through a volley of factual and less-than-factual witness accounts. Morris told interviewer Scott Tobias in 2011, “People may give varying accounts of [the truth], which are self-serving, are self-deceiving, are wrong… But none of that means that there is no underlying truth or reality to be uncovered.” In this sense, Morris’ assertion of truth in The Thin Blue Line proves to be under the surface, if not presumed by the audience, and yet an urgent aspect of the presentation. Morris’ presumptive assertion is declared in largely nonverbal forms, such as when the filmmaker crosscuts between his interviewee and another visual element that, through montage, creates an implied assertion. Consider again the sequence where Miller talks about her admiration for detective work. Morris cuts away to footage of a silly black-and-white detective film, suggesting that Miller associates detective work with an escapist fantasy of fictional cinema, thus tainting her perspective.

Beyond its interviews, The Thin Blue Line uses wonderful (and controversial) reenactments to visualize details from the case—some accurate, some false, some misremembered. Documentaries do not use reenactments, generally; they are more often employed by educational or propagandistic nonfiction films. Morris’ use of them remains even more unconventional because, in some instances, the reenactments represent a witness account that is later proved to be inaccurate or untrue. They visualize the witness accounts and allow the viewer to see what the witness claims happened, regardless of its accuracy. When Morris juxtaposes two reenactments, one true and the other false, the effect on the audience is more dramatic in part because the contrast is visible, instead of just testimony; in part because of its familiar stylization as a fictional film. The outcome for the viewer is more convincing and engaging, and furthermore, reveals what Morris sees as the underlying truth of the Adams case: that multiple perspectives—some falsified, some misremembered, some coerced by corrupt officials—fed a wrongful conviction. In this sense, the truth resides somewhere between the facts and testimonies, twisted by the perspectives of those involved.

Beyond its interviews, The Thin Blue Line uses wonderful (and controversial) reenactments to visualize details from the case—some accurate, some false, some misremembered. Documentaries do not use reenactments, generally; they are more often employed by educational or propagandistic nonfiction films. Morris’ use of them remains even more unconventional because, in some instances, the reenactments represent a witness account that is later proved to be inaccurate or untrue. They visualize the witness accounts and allow the viewer to see what the witness claims happened, regardless of its accuracy. When Morris juxtaposes two reenactments, one true and the other false, the effect on the audience is more dramatic in part because the contrast is visible, instead of just testimony; in part because of its familiar stylization as a fictional film. The outcome for the viewer is more convincing and engaging, and furthermore, reveals what Morris sees as the underlying truth of the Adams case: that multiple perspectives—some falsified, some misremembered, some coerced by corrupt officials—fed a wrongful conviction. In this sense, the truth resides somewhere between the facts and testimonies, twisted by the perspectives of those involved.

Morris’ creative method of asserting truth through expressive and contradictory cinematic reenactments does not conform to Plantinga’s definition of a documentary—nor any other definition. Rather, these moments seem like fictional cinema imposed on nonfictional cinema as a function of art. Granted, Plantinga allows a certain amount of freedom in a film’s willingness to show visuals that do not directly support an assertion; however, in the case of Morris’ reenactments, the film creates false positives by demonstrating a witness’ point-of-view, as Morris is aware that what he shows the audience isn’t accurate. The film’s false reenactments provide a representation of what their respective witnesses testified to, serving to create a dramatic conflict when two witness accounts differ. At first, the dramatic reenactment segment of the traffic stop seems strange and stylish for a documentary. But once you see it again from another perspective and realize what Morris is doing, you get the impression that what we’re seeing is supposed to be how the witness envisions it in their mind (or at least that’s what they claim). We can see how the witnesses have perhaps built up the scene in their mind. Additionally, the expressionistic way in which Morris shoots those segments lends them dramatic substance; his stylistic approach connects his documentary to a similarly-themed thriller, using the same type of cinematics to engage us on a familiar, emotional level.

Indeed, such dramatically lit scenes seem more suitable for a fictional film; specifically, a neo-noir—the treatment recalls moments from the Coen brothers’ Blood Simple (1984)—and they speak to Morris’ concentration on aesthetics throughout The Thin Blue Line. The reenactments contain fluid camerawork and bold lighting choices, representing what film theorist Linda Williams called an “abandonment” of documentary realism. At other times, Morris cuts to a red police light rotating, an image that has no supportive function to his assertion and provides no evidence; instead, it exists as a purely aesthetic flourish. In another sequence, Morris uses slow-motion to enhance the dramatic significance when police officer Teresa Turko hears the first gunshots that struck her partner. Wood and Turko had purchased some fast-food before the fateful traffic stop, and upon hearing the gunshots, Turko either dropped or threw out her milkshake—which Morris shows spilling onto the ground with an almost fetishized significance. More than strengthening Morris’ assertive intent of The Thin Blue Line, such touches create a playful visual rhythm that breaks up the interview segments. Likewise, the persistent, hypnotic score by Philip Glass supports the film’s narrative thrust, adding weighty inflections to the interviews and reenactments, and further supporting the film’s comparisons to neo-noir.

Indeed, such dramatically lit scenes seem more suitable for a fictional film; specifically, a neo-noir—the treatment recalls moments from the Coen brothers’ Blood Simple (1984)—and they speak to Morris’ concentration on aesthetics throughout The Thin Blue Line. The reenactments contain fluid camerawork and bold lighting choices, representing what film theorist Linda Williams called an “abandonment” of documentary realism. At other times, Morris cuts to a red police light rotating, an image that has no supportive function to his assertion and provides no evidence; instead, it exists as a purely aesthetic flourish. In another sequence, Morris uses slow-motion to enhance the dramatic significance when police officer Teresa Turko hears the first gunshots that struck her partner. Wood and Turko had purchased some fast-food before the fateful traffic stop, and upon hearing the gunshots, Turko either dropped or threw out her milkshake—which Morris shows spilling onto the ground with an almost fetishized significance. More than strengthening Morris’ assertive intent of The Thin Blue Line, such touches create a playful visual rhythm that breaks up the interview segments. Likewise, the persistent, hypnotic score by Philip Glass supports the film’s narrative thrust, adding weighty inflections to the interviews and reenactments, and further supporting the film’s comparisons to neo-noir.

Somewhere amid the false testimonies, cops keen to avenge their fallen comrade, and District Attorney Douglas Mulder, who was eager to maintain his flawless conviction record, The Thin Blue Line reveals itself to be less about the wrongful conviction of Randall Adams and more about how truth is not always as simple as it appears to be. Morris’ lingering theme brings into question the authority of the police, the unreliability of witnesses, and even images themselves. After all, many of the images Morris shows early in the film prove to be intentionally inaccurate, displayed if only to reinforce a counterpoint made later. The film, therefore, presents an unnerving contradiction as its purpose: that witnesses and images remain valued as objective evidence to keep not only the wheels of justice turning, but also the documentary format. However, those witnesses and images are not necessarily accurate or representative of the truth in all cases, thus questioning how much faith should be placed in the “thin blue line” of authority that lies between civilization and “chaos.” Even though this lesson has been taught again and again through edited or carefully structured photographs, false and misremembered testimonies, or countless cases of wrongful conviction, a general faith and desire for objective images remains among most people. Morris dazzlingly reinforces Akira Kurosawa’s lesson from Rashomon (1950), that the “real world” exists only in a series of personal truths and perceptions, by considering how, in the Adams case, lies reveal the truth.

Audiences today embrace documentaries as factual, or at least truthful. If there is any worthy consequence to the continuing success of reality TV, it is that people yearn for reality (even though such sources are not providing reality). And yet, the paradox remains that, in spite of a prevalent desire for reality, documentary filmmakers shape and subjectify reality to form something other than an objective reality. This is the subject of The Thin Blue Line, a film that provides an exhilarating study into the subjectivity of its interviewees, and by proxy, or perhaps more intentionally so, the subjectivity of documentaries. If the objective-minded cinéma vérité documentary relies on images and distanced observation, then it serves little purpose to engage, question, and investigate its subject in Morris’ view—and therefore, cinéma vérité will inherently fail to discover the subject’s truth and accurately depict reality. Morris has little faith in the objectivity of such documentaries, as truth is discovered only through inquiry and a critical consideration of the so-called evidence. His approach, according to traditional definitions of the documentary, places aspects of the film outside of the documentary realm, or at least on the far end of unconventional. Whereas, Morris has called The Thin Blue Line more a nonfiction film than a documentary, and he calls himself a detective-director rather than a documentarian—two self-appraisals that reveal Morris as a filmmaker more interested in the dynamics between art and truth than your typical documentarian. The film’s lasting genius is that, through his unique and obsessive investigative process, Morris turns his viewer into a detective on the prowl for truth, second-guessing and questioning everything—a consequence that, with any luck, will continue beyond this film.

Audiences today embrace documentaries as factual, or at least truthful. If there is any worthy consequence to the continuing success of reality TV, it is that people yearn for reality (even though such sources are not providing reality). And yet, the paradox remains that, in spite of a prevalent desire for reality, documentary filmmakers shape and subjectify reality to form something other than an objective reality. This is the subject of The Thin Blue Line, a film that provides an exhilarating study into the subjectivity of its interviewees, and by proxy, or perhaps more intentionally so, the subjectivity of documentaries. If the objective-minded cinéma vérité documentary relies on images and distanced observation, then it serves little purpose to engage, question, and investigate its subject in Morris’ view—and therefore, cinéma vérité will inherently fail to discover the subject’s truth and accurately depict reality. Morris has little faith in the objectivity of such documentaries, as truth is discovered only through inquiry and a critical consideration of the so-called evidence. His approach, according to traditional definitions of the documentary, places aspects of the film outside of the documentary realm, or at least on the far end of unconventional. Whereas, Morris has called The Thin Blue Line more a nonfiction film than a documentary, and he calls himself a detective-director rather than a documentarian—two self-appraisals that reveal Morris as a filmmaker more interested in the dynamics between art and truth than your typical documentarian. The film’s lasting genius is that, through his unique and obsessive investigative process, Morris turns his viewer into a detective on the prowl for truth, second-guessing and questioning everything—a consequence that, with any luck, will continue beyond this film.

Bibliography:

Musser, Charles. “The Thin Blue Line: A Radical Classic.” Criterion. 26 March 2015. https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/3500-the-thin-blue-line-a-radical-classic

Plantinga, Carl. “What a Documentary Is, After All.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 4/1/2005, Vol. 63, Issue 2, pp. 105-117.

Tobias, Scott. “Interview: Errol Morris.” The AV Club. http://www.avclub.com/article/errol-morris-58855. Accessed 12 February 2017.

Williams, Linda. “Mirrors without Memories: Truth, History, and The Thin Blue Line.” Documenting the Documentary, edited by Barry Keith Grant and Jeannette Sloniowski, Wayne State University Press, 2014, pp. 385-403.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review