The Definitives

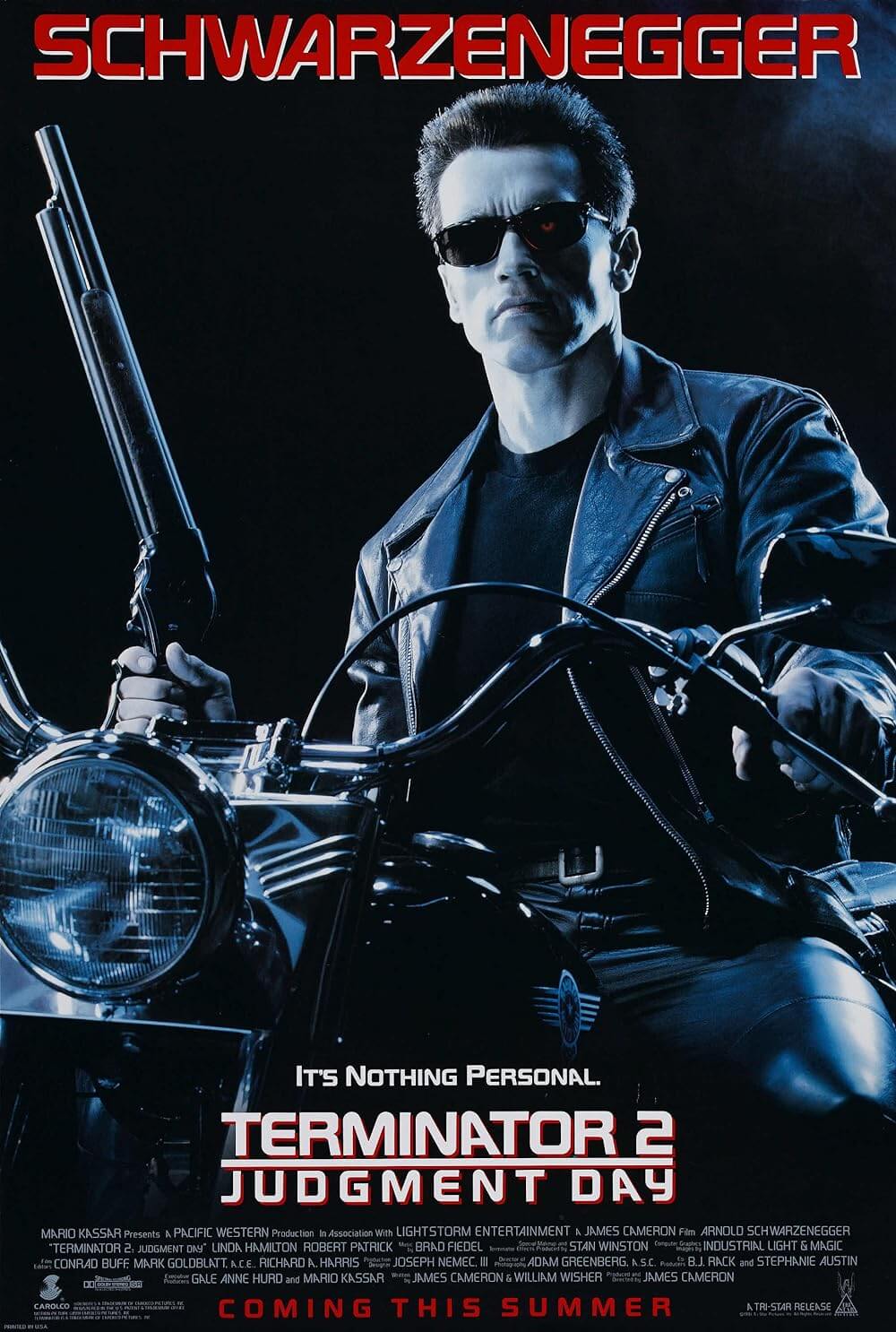

The Terminator

Essay by Brian Eggert |

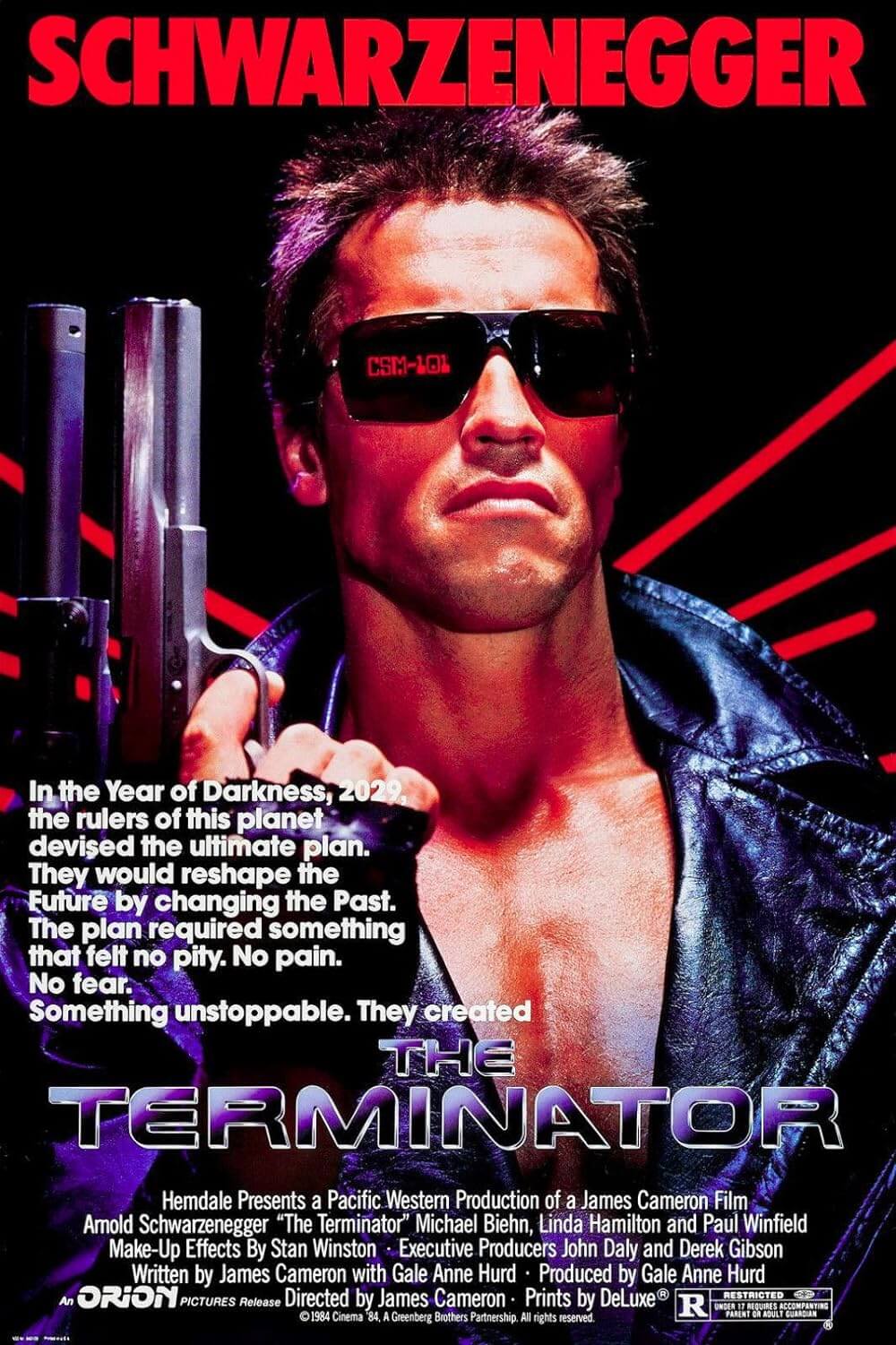

The Terminator is James Cameron’s first cinematic foray into a career-long obsession with heavy tech, strong women, and relentless action. Upon its arrival in 1984, the impressive, brutal blend of science fiction and propulsive chases boasted striking special effects, gave a superstar-making role to Arnold Schwarzenegger, and, for better or worse, launched an enduring franchise. Cameron has since remarked that now he sees only his mistakes and what he would do differently with the film. However, the rough edges of this scrappy, tactile production show evidence of a filmmaker at his most inventive and resourceful. It’s the purest expression of Cameron’s raw, handcrafted talent as an artist, storyteller, technician, and genre enthusiast. Cameron’s intense momentum and prescient ideas sustain the film today, even after repeated viewings and a deep saturation of its iconography into the culture. The film’s sheer entertainment value—marked by its sharp B-movie plot and A-level visuals, focused narrative thrust, and indelible imagery—remains intact forty years later. And while Cameron would make better, more ambitious, and certainly more successful projects in the decades to come, none would feel so foundational to Cameron’s auteurism as The Terminator, which offers the unfiltered essence of his abilities and preoccupations.

Cameron’s film looks better than most in its genre from this era—a period in which practical makeup and effects purveyors regularly tried to outdo each other. To that extent, Stan Winston’s robot exoskeleton and impressive miniature work based on Cameron’s designs still look stunning, even though the use of stop-motion animation in live-action features, along with several other techniques used by Winston, has become outmoded. Cameron put every bit of his considerable knowledge about filmmaking artistry to work—matte paintings, miniatures, and all manner of in-camera effects—to create grim visions of the machine-dominated apocalypse. Yet, scholar Sean French described the movie admiringly as “cheap, grimy, rough, and analogue” in his BFI monograph, owing to Cameron’s necessity to stretch his shockingly small initial budget of $4.5 million. The hugely popular cyborg-themed movie would suffer the same fate as many R-rated franchises of the 1980s. Its impressive box-office run was followed by a tempering of the material in sequels to appease a juvenile audience (and their parents). And while movie fanatics continue to speculate and read The Terminator as a Christ allegory, Cameron intended to put what would become lifelong interests into an unyielding and undiluted framework.

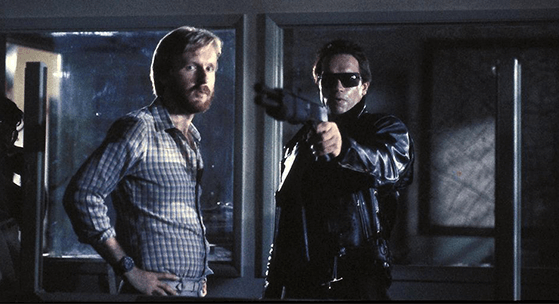

Cameron’s scenario involves a cybernetic assassin called a Terminator (Schwarzenegger) traveling back in time from the machine-ruled future of 2029 to 1984, where it hunts and kills women named Sarah Connor, hoping to find the mother of John Connor, the rebel leader of its time. The correct Sarah Connor (Linda Hamilton) is saved by a human soldier named Kyle Reese (Michael Biehn), who is sent back by Sarah’s future son to protect her from the Terminator. These three intersect, leading to breakneck chases and shoot-outs that end with Reese and Sarah’s capture by the police. With Sarah under police protection, they gradually convince her that Reese is crazy, paranoid, and delusional; the Terminator’s ability to survive after severe injuries is explained away as body armor and PCP drug use. Just then, the Terminator launches an attack on the Police Headquarters where Sarah is held, kills a dozen or so cops, and starts the chase once more. Sarah and Reese barely escape with their lives. They have a few hours together to catch their breath and discuss the bleak future. After hearing Reese’s stories about how John sent him back and his demanding post-armageddon lifestyle, wherein he confesses he’s a virgin, Sarah and Reese end up in bed, where they conceive the future’s savior. In the finale, Reese dies trying to stop the Terminator, and Sarah crushes the killer machine in a factory press, surviving with the knowledge that her unborn son will lead humanity after what is known as Judgment Day: when the machines instigate a nuclear war and take over.

Of course, the entire Terminator franchise is rooted in a time-travel paradox. After all, how could there have been a John Connor to send Reese back in time if Reese was indeed his father? Consider time like a straight line moving forward. As the line progresses, Sarah Connor gives birth to her son, and he grows up to lead the human rebellion against the machines of the evil computer Skynet. The timeline loops back when John sends Reese into the past to protect his mother, and he impregnates her, and the straight line now has a loop. But it had to be a straight line before it could become a loop. Does this mean someone must have impregnated Sarah on the original timeline strain to create John in the first place, because without him, Reese would have never been sent back? If so, who is this other guy? We never know. He must exist, however, because, without him, Cameron’s wishy-washy theory leaves only, well, a paradox. Never mind how the paradox resolves—it never does, intentionally—because getting hung up on such ideas misses the point. Instead, Cameron’s intent is to cram many of his beloved sci-fi concepts and inspirations, including temporal paradoxes, into a single film.

Of course, the entire Terminator franchise is rooted in a time-travel paradox. After all, how could there have been a John Connor to send Reese back in time if Reese was indeed his father? Consider time like a straight line moving forward. As the line progresses, Sarah Connor gives birth to her son, and he grows up to lead the human rebellion against the machines of the evil computer Skynet. The timeline loops back when John sends Reese into the past to protect his mother, and he impregnates her, and the straight line now has a loop. But it had to be a straight line before it could become a loop. Does this mean someone must have impregnated Sarah on the original timeline strain to create John in the first place, because without him, Reese would have never been sent back? If so, who is this other guy? We never know. He must exist, however, because, without him, Cameron’s wishy-washy theory leaves only, well, a paradox. Never mind how the paradox resolves—it never does, intentionally—because getting hung up on such ideas misses the point. Instead, Cameron’s intent is to cram many of his beloved sci-fi concepts and inspirations, including temporal paradoxes, into a single film.

Cameron received his start working for Roger Corman—just as Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Jonathan Demme, and Ron Howard had done before him. His first industry job entailed making models for Battle Beyond the Stars (1980), Corman’s knockoff of Star Wars (1977) and Seven Samurai (1954). But circumstances on that production led to Cameron going from model maker to heading the art direction, production design, matte paintings, and special effects. Quickly earning a reputation as an artist and technician who could design elaborate concepts and then realize them physically, Cameron landed his next job, making the bleak cityscapes in John Carpenter’s Escape from New York (1981). After that, Corman hired Cameron again for Galaxy of Terror (1981), where he talked his way into a second-unit director role. This earned the attention of Italian producers working on a sequel to Corman’s production of Piranha (1978). Ovidio Assonitis saw Cameron at work and signed him to direct his first feature, Piranha II: The Spawning (1981). But the impulsive producer fired him and took over directing duties shortly after shooting began. Worse, Assonitis refused to remove Cameron’s name—which, had he not been broke at the time, Cameron would have contested with an attorney. And so, Cameron’s first onscreen director’s credit appears on a movie he barely helmed.

While in Rome for Piranha II, Cameron couldn’t afford to eat and had been working late hours, sneaking into Assonitis’ editing bay to recut what would be his first full-length feature. Later, those cuts would be undone by Assonitis. Eventually, Cameron collapsed, and the resulting fever dream became the impetus of The Terminator. According to Cameron’s self-mythologizing, he saw a robot emerging from a fire that inspired the image of the Terminator. From that initial image, he began devising a script, fleshing out his concept with ideas inspired by two Harlan Ellison-penned episodes of The Outer Limits called “Soldier” and “Demon with a Glass Hand”—a detail that would later earn the distributors some legal trouble. Cameron also looked at what was successful then, resolving to build his story structure on a slasher foundation. He borrowed from Carpenter’s low-budget breakthrough, Halloween (1978), complete with a stalker and a Final Girl. But then, Cameron also wanted to incorporate adrenaline-fueled action modeled after The Road Warrior’s (1981) fast-paced car chases.

After working his passion for genre and action into his screenplay, Cameron showed an early draft to Gale Anne Hurd, who served as Corman’s assistant production manager on Battle Beyond the Stars, and whom Cameron would later marry. Selling her the script for a dollar on a verbal agreement that she would produce and he would direct when the production sold, Cameron also agreed to give Hurd credit on the screenplay for providing feedback. Their names on the script would reinforce to any studio or investor that they were a package deal. And while Hurd often receives credit for Sarah Connor being such a strong female lead, those ideas belong to Cameron. Rather, Hurd did no actual writing, according to Cameron. The plan worked, and the two piqued the interest of distributors at Orion Pictures. With a distributor set, Hurd and Cameron approached the head of a small-fry financier, John Daly at Hemdale Film Corporation, who agreed to finance The Terminator’s production, with contributions from Orion for theatrical and HBO for television rights. Though Corman’s training ground for directors had prepared Cameron to helm a low-budget science-fiction production, his ambitious vision meant his $4.5 million budget would eventually rise to $6 million.

After working his passion for genre and action into his screenplay, Cameron showed an early draft to Gale Anne Hurd, who served as Corman’s assistant production manager on Battle Beyond the Stars, and whom Cameron would later marry. Selling her the script for a dollar on a verbal agreement that she would produce and he would direct when the production sold, Cameron also agreed to give Hurd credit on the screenplay for providing feedback. Their names on the script would reinforce to any studio or investor that they were a package deal. And while Hurd often receives credit for Sarah Connor being such a strong female lead, those ideas belong to Cameron. Rather, Hurd did no actual writing, according to Cameron. The plan worked, and the two piqued the interest of distributors at Orion Pictures. With a distributor set, Hurd and Cameron approached the head of a small-fry financier, John Daly at Hemdale Film Corporation, who agreed to finance The Terminator’s production, with contributions from Orion for theatrical and HBO for television rights. Though Corman’s training ground for directors had prepared Cameron to helm a low-budget science-fiction production, his ambitious vision meant his $4.5 million budget would eventually rise to $6 million.

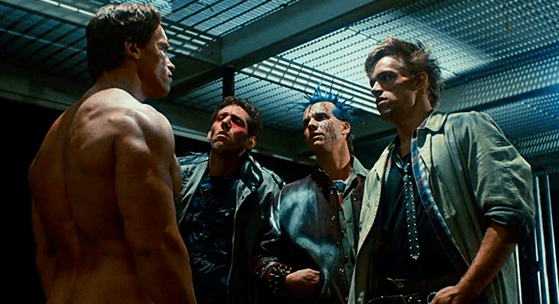

But first, the director needed a cast. Cameron initially had no intention of casting Schwarzenegger, the seven-time Mr. Olympia and five-time Mr. Universe winner, whom the backers wanted to play the heroic Kyle Reese. The director even planned to pick a fight with the Austrian actor so that he could report back that the bodybuilder wouldn’t work. But after their initial lunch meeting, Cameron realized the Conan the Barbarian (1982) star would make a great Terminator. The two also hit it off personally. With Cameron hailing from Canada, both were immigrants in Hollywood. They each had the self-reliance, wild ambition, and talent to back up their otherwise unbridled confidence, and they recognized these qualities in each other. Moreover, Cameron knew that Schwarzenegger wouldn’t work as the Terminator, which was supposed to be an infiltration unit that could convincingly blend in with the human resistance of the future. Schwarzenegger only stood out. And why would the machines design a cyborg with an Austrian accent? But Cameron also knew, as he told WIRED, that “the beauty of movies is that they don’t have to be logical. If there’s a visceral, cinematic thing happening that the audience likes, they don’t care if it goes against what’s likely.”

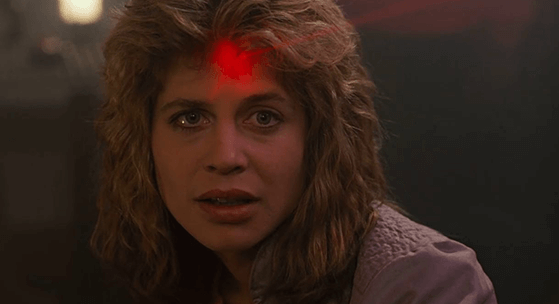

Cameron also went against type in creating Sarah Connor, a character whose strength would carry on through the entire movie franchise, including a TV show with her name. Building a strong female character wasn’t a feminist statement, nor did he want to make the genre equivalent of the Virgin Mary, who gives birth to humanity’s savior. His choice was artistic and commercially strategic. For starters, there hadn’t been a female hero in action movies before outside of Blaxploitation cinema. Cameron also felt a female lead would interest women in the audience who might not be interested in cyborgs, the apocalypse, and shoot-outs. But casting Connor proved a challenge. In Cameron’s script, Sarah Connor is “pretty in a flawed, accessible way,” and her “vulnerable quality masks a strength she doesn’t know exists.” Jennifer Jason Leigh and Rosanna Arquette were considered, but after casting Schwarzenegger, the production’s casting budget had been spent, leaving no hope for a name to play the waitress from Big Jeff’s burger joint who ends up mothering the future resistance leader. He landed on Linda Hamilton, who had just wrapped work on Children of the Corn (1984), distributed by Corman’s New World Pictures. Similarly, when Cameron finally cast Reese, he considered bigger stars but selected the little-known Michael Biehn, whose most significant role was playing Lauren Bacall’s stalker in the 1981 made-for-TV movie The Fan.

With the budget stretched thin, the production shot in Los Angeles. The crew endured a heatwave and the summertime swarms of medflies that threatened California agriculture in the 1980s, not to mention medfly repellent sprayed over the city by government helicopters. But working under such conditions, on a production over which he had creative control, Cameron was in his element. “He had a kid-in-a-candy-store feeling about him,” observed Biehn. Less money meant more creative freedom, after all. And his experience with Corman meant he could do everyone’s job well, contributing to cinematographer Adam Greenberg’s lighting decisions or going so far as to personally demonstrate how Schwarzenegger’s stunt double should land on the hood of a car. Rarely did he rely on anyone else for input. When staging a semi-truck explosion, he conceived of how to cut from an actual semi to a less expensive miniature for the detonation. Corman had taught him how to cut costs and innovate, and he remained confident and hands-on because he had considered every detail well in advance, and each of these choices pointed in the same direction.

With the budget stretched thin, the production shot in Los Angeles. The crew endured a heatwave and the summertime swarms of medflies that threatened California agriculture in the 1980s, not to mention medfly repellent sprayed over the city by government helicopters. But working under such conditions, on a production over which he had creative control, Cameron was in his element. “He had a kid-in-a-candy-store feeling about him,” observed Biehn. Less money meant more creative freedom, after all. And his experience with Corman meant he could do everyone’s job well, contributing to cinematographer Adam Greenberg’s lighting decisions or going so far as to personally demonstrate how Schwarzenegger’s stunt double should land on the hood of a car. Rarely did he rely on anyone else for input. When staging a semi-truck explosion, he conceived of how to cut from an actual semi to a less expensive miniature for the detonation. Corman had taught him how to cut costs and innovate, and he remained confident and hands-on because he had considered every detail well in advance, and each of these choices pointed in the same direction.

The Terminator also marked Cameron’s first of many collaborations with Stan Winston, who worked from Cameron’s detailed designs to build the Terminator exoskeleton. What remains special about Cameron and Winston’s efforts on The Terminator is that the special effects serve the efficient storytelling. Unlike moments in, say, Cameron’s Avatar films that luxuriate in the awe and wonder of Pandora with indulgent CGI deviations, The Terminator is lean and mean in its visual and narrative economy—a budgetary necessity. Cameron comes close to indulgence when the action slows down as the Terminator repairs its damage in a dingy room, operating on its robotic wrist tendons and clearing out the smashed flesh around its eye. Then again, the scene provides a glimpse of the cyborg’s internal makeup and, a moment later, its programming when a manager knocks on the door, and the Terminator selects “Fuck you, asshole” from a list of potential phrases. To be sure, it’s about more than just visceral action movie mayhem—Cameron even manages a reference to Luis Buñuel’s surrealist film Un Chien Andalou (1929) when the cyborg slices open his eye to remove the dead tissue. Winston and Cameron would collaborate again on Aliens (1986) and Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991), and Winston earned Oscars for his work on both.

The special effects take their cue from the narrative, which has had nearly every ounce of fat removed. Though efficient, focused, and small-scale compared to its successors, The Terminator is nonetheless rife with the characteristic excesses of 1980s entertainment. In his book Blockbuster about this era of Hollywood, Tom Shone characterized the appeal of this and many other entertainments as “flabbergasted extremity.” What could be more extreme or flabbergasting than a humongous, six-foot-two Austrian cyborg driving a truck into a police station and mowing down a whole force without taking much damage? While audiences weren’t exactly rooting for the Terminator, they were delighted by the shocks and visceral action the killer cyborg brought to the screen. Although Cameron made a brutal movie in which the Terminator kills street punks, Sarah’s horny roommate and her boyfriend, and other women named Sarah Connor, the Terminator is the source of that entertainment value. Audiences wanted more, regardless if he was the antagonist—a trend that extended to other ’80s franchises modeled after slashers. Just as Freddy Krueger from A Nightmare on Elm Street, released the same year as The Terminator, became increasingly more of a prankster and the villain the audience loves to hate with each sequel, the T-800 became the good guy in subsequent Terminator movies.

While Cameron wields science-fiction concepts, The Terminator is an action movie first and doesn’t explore the dynamics of time travel with much depth. When Reese explains the experience of traveling through time, Sarah says the concept makes her head spin. She would rather talk about the women from Reese’s time. He calls them “good fighters” before admitting he’s never had anyone special. His confession that he’s loved Sarah from the future is a revelation meant to be romantic, and at the time, most critics agreed. Roger Ebert described their love story as told in “strong, simple terms that are surprisingly romantic and effective.” Today, Reese’s love—based on a picture of Sarah given to him by John Connor, from which he “memorized every line, every curve”—feels like the confession of a stalker, spoken with Biehn’s same intensity from The Fan. “I came across time for you, Sarah. I love you,” he says, assured yet somehow wounded. “I always have.” The ensuing love scene, mostly awkward, remains the only sex scene in any Cameron film for good reason; it’s shot mechanically and without passion. Fortunately, Cameron had enough sense to leave Jack and Rose’s lovemaking to the imagination in Titanic, signaled only by her hand against the steamy car window. If The Terminator’s romance subplot and sex scene register as clunky today, Cameron conceives his future world and visual agenda with compelling detail.

While Cameron wields science-fiction concepts, The Terminator is an action movie first and doesn’t explore the dynamics of time travel with much depth. When Reese explains the experience of traveling through time, Sarah says the concept makes her head spin. She would rather talk about the women from Reese’s time. He calls them “good fighters” before admitting he’s never had anyone special. His confession that he’s loved Sarah from the future is a revelation meant to be romantic, and at the time, most critics agreed. Roger Ebert described their love story as told in “strong, simple terms that are surprisingly romantic and effective.” Today, Reese’s love—based on a picture of Sarah given to him by John Connor, from which he “memorized every line, every curve”—feels like the confession of a stalker, spoken with Biehn’s same intensity from The Fan. “I came across time for you, Sarah. I love you,” he says, assured yet somehow wounded. “I always have.” The ensuing love scene, mostly awkward, remains the only sex scene in any Cameron film for good reason; it’s shot mechanically and without passion. Fortunately, Cameron had enough sense to leave Jack and Rose’s lovemaking to the imagination in Titanic, signaled only by her hand against the steamy car window. If The Terminator’s romance subplot and sex scene register as clunky today, Cameron conceives his future world and visual agenda with compelling detail.

Applying a style Cameron coined “tech noir,” the film’s nighttime Los Angeles exists in shadows, neon, grime, and machines that foretell the laser-blasting juggernauts of Reese’s apocalyptic future—he even named the nightclub where Sarah takes refuge after the concept. Now a relatively well-known term, tech noir approaches technology skeptically and takes a cynical view of the future, portraying so-called advancements as a potentially dangerous force that threatens to turn our world into a dystopia. Stylistically, The Terminator warns about the future with heavy shadows, severe cyborg designs, and a bleak outlook, all accented by Brad Fiedel’s instantly iconic electronic score. Still, if his allusions to Harlan Ellison, John Carpenter, and George Miller are any indication, Cameron’s approach quotes countless other films and filmmakers. The tech noir aesthetic? He elaborates on the idea from the German expressionist work of Fritz Lang on Metropolis (1927) and Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982). The notion that a global disaster might be thwarted by the unlikeliest of heroes? He may have borrowed the idea from Alfred Hitchcock thrillers about an average person thrust into a conspiracy, such as The 39 Steps (1935) or North by Northwest (1959). The point-of-view shots from the Terminator’s perspective? They were modeled after similar first-person shots from the opening of Halloween. The image of a robotic skeleton under a human face? Yul Brynner’s appearance in Westworld (1973) likely inspired it. Listing these examples is not intended to discredit Cameron but rather to praise his ability—almost absent among most of today’s genre filmmakers—to use their inspirations without making the result feel like a series of references or quotations.

When The Terminator was released, critics largely praised Cameron’s work as virtuoso filmmaking over a B-movie template. Richard Corliss of Time magazine placed it on his Top 10 list for 1984. The Los Angeles Times praised its “clever special effects and sly humor.” Audiences consumed the ultra-violent, R-rated proceedings, earning the film $78 million at the box office against bigger studio productions such as David Lynch’s Dune and 2010: The Year We Make Contact. Some celebrated elements of the film remain odd, such as Schwarzenegger’s resultant popularity. Looking back, it’s curious that the Austrian bodybuilder’s career took off from this launchpad and not those of Hamilton or Biehn. After all, Hamilton undergoes an impressive transformation, but her career would remain overshadowed by her role as Sarah Connor. Biehn, too, plays the sympathetic male hero and displays ferocity and sensitivity, whereas Schwarzenegger is static and unappealing. Cameron would use Biehn twice more on Aliens and The Abyss (1989), both with incredible results; still, he’s overlooked today in favor of Schwarzenegger. And what is it about the line “I’ll be back” that stuck with people? Within the story, it’s a flat reading that registers as almost deadpan humor, punctuated by the Terminator’s assault on the police station. But Schwarzenegger has built a career out of that line, using it more than ten more times in various action movies between 1985 and 2019.

In the decades since its release, The Terminator has become something more than an action movie about time travel, a killer cyborg, and the impending apocalypse. It has epitomized warnings about artificial intelligence. Computer scientists continue to raise alarms about the threat of AI, with countless journalists and scientists alluding to Cameron’s Skynet to illustrate the dangers humanity faces, or more accurately, creates. Cameron acknowledges, “It is not the machines that will destroy us, it is ourselves. However, we will use machines to do it.” Cameron worries about what AI learns from humanity and how it will apply those lessons. Cameron told CTV News, “They’re either building it to dominate market shares. So what are you teaching it? Greed. Or you’re building it for defensive purposes, so you’re teaching it paranoia.” Today, humans use automated drones and targeting computers for carrying out military strikes. But what happens when AI and those weapons begin communicating in ways not intended by humans? “I warned you guys in 1984,” Cameron said, only half joking, “and you didn’t listen.”

In the decades since its release, The Terminator has become something more than an action movie about time travel, a killer cyborg, and the impending apocalypse. It has epitomized warnings about artificial intelligence. Computer scientists continue to raise alarms about the threat of AI, with countless journalists and scientists alluding to Cameron’s Skynet to illustrate the dangers humanity faces, or more accurately, creates. Cameron acknowledges, “It is not the machines that will destroy us, it is ourselves. However, we will use machines to do it.” Cameron worries about what AI learns from humanity and how it will apply those lessons. Cameron told CTV News, “They’re either building it to dominate market shares. So what are you teaching it? Greed. Or you’re building it for defensive purposes, so you’re teaching it paranoia.” Today, humans use automated drones and targeting computers for carrying out military strikes. But what happens when AI and those weapons begin communicating in ways not intended by humans? “I warned you guys in 1984,” Cameron said, only half joking, “and you didn’t listen.”

Years later, critic and historian Richard Schickel accurately described The Terminator for a 1991 reassessment in Entertainment Weekly: “What originally seemed a somewhat inflated, if generous and energetic, big picture, now seems quite a good little film.” Although many Terminator franchise fans agree that the sequel, Terminator 2: Judgment Day, is a superior film in every respect—a view this writer does not share—the original has a preferable, modest quality that would never be seen in Cameron’s work again. The Terminator shows Cameron at his most essential. It’s a brutal piece of work that, thematically, harbors a deep-rooted skepticism about the effectiveness of the police, the establishment, and technology in protecting people, yet values those strong-willed few, such as Sarah Connor and Kyle Reese, who fight for survival. Best of all, it boasts the aesthetic purity of a young artist making his first low-budget film on his terms, proving how far he could stretch his imagination with few resources. How many other filmmakers in 1984 could take a modest budget and craft memorable characters in a sci-fi scenario that has inspired countless imitators? Cameron built a lasting cinematic legacy and iconography with his first film. And it wouldn’t be for the last time.

(Note: This essay was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on February 28, 2024.)

Bibliography:

Cornea, Christine. Science Fiction Cinema: Between Fantasy and Reality. Rutgers University Press, 2007.

Daly, Steve. “No Pity, No Fear, No End.” WIRED, 17 April 2009.

French, Sean. The Terminator. British Film Institute; 2nd edition, 2021.

Keegan, Rebecca. The Futurist: The Life and Films of James Cameron. Three Rivers Press, 2009.

Nathan, Ian. James Cameron: A Retrospective. Palazzo Editions, 2012.

“One-on-one interview with filmmaker James Cameron.” CTV News, 18 July 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YiT3uzZtRb0. Accessed 2 February 2024.

Schickel, Richard. “The Terminator.” Entertainment Weekly. 13 December 1991. https://ew.com/article/1991/12/13/terminator-2/. Accessed 2 February 2024.

Shone, Tom. Blockbuster: How Hollywood Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Summer. Free Press, 2004.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review