The Definitives

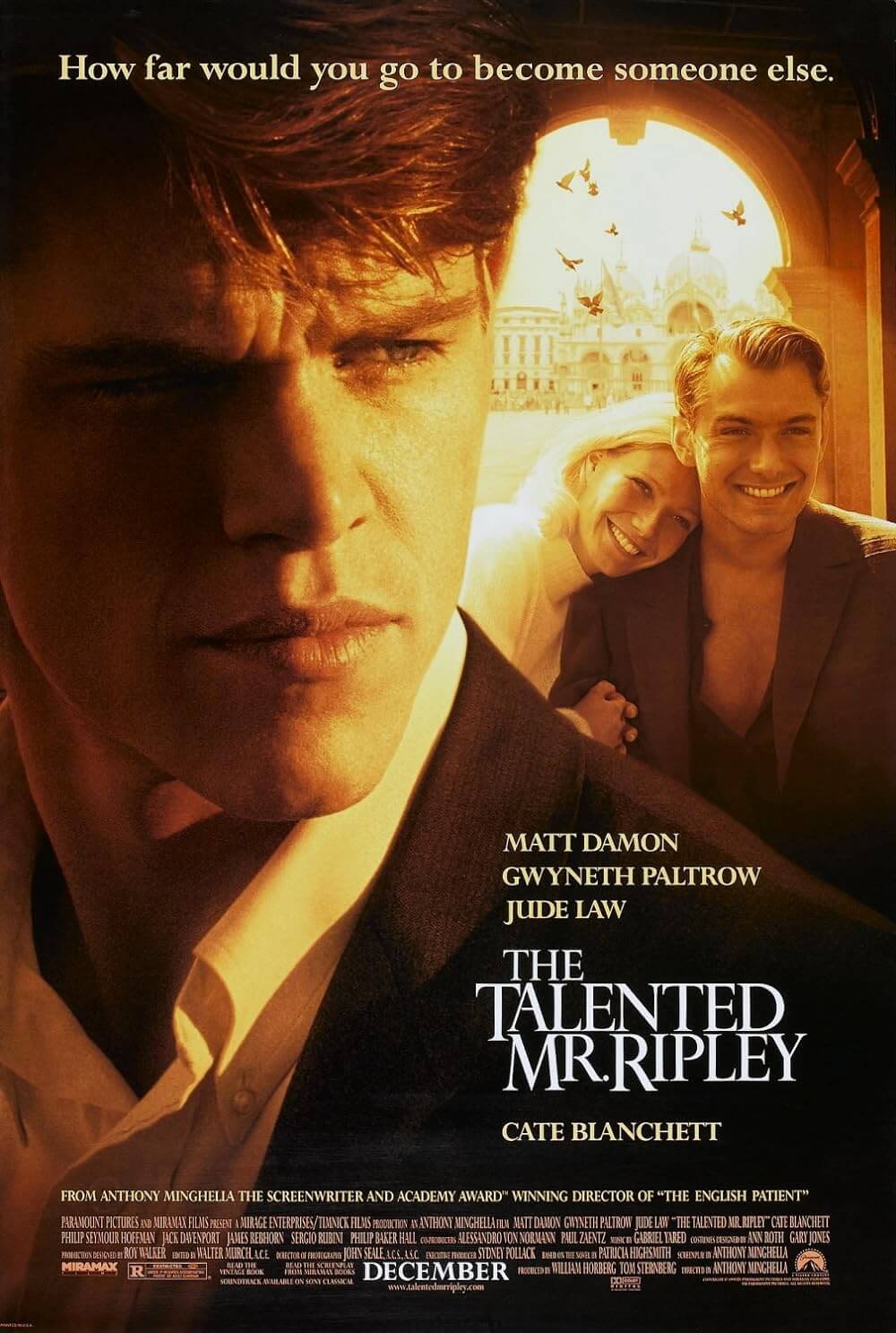

The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Published in 1955, Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr. Ripley, the first novel in a series of five, follows the charming but nihilistic Tom Ripley, an enigmatic character with all the makings of a psychopath. Capable of murder and deceit on a grand scale, his wickedness is offset by his intelligence and enduring charisma, his passion for a lifestyle of affluence, art, and sophistication. In Anthony Minghella’s 1999 adaptation of the novel, the chameleon character impersonates others by mimicking voices and forging signatures; he lies about himself to hide his humble origins; he turns on those closest to him when the tides of friendship change; and when cornered, he murders to preserve his secrets. Yet, in the film’s title sequence, a string of adjectives alternates onscreen between The and Mr. Ripley before Talented appears: mysterious, yearning, secretive, sad, lonely, troubled, confused, loving, musical, gifted, intelligent, beautiful, tender, sensitive, haunted, and passionate. Do these words sound like the descriptions of a cold-blooded killer?

While great, Highsmith’s novel views Tom Ripley as a villain-protagonist, her narrative flowing with a manipulative writing style set from the perspective of her anti-hero. Largely an investigation into how an author can convince an audience to sympathize with an unscrupulous character through persuasive, cleverly written prose, her plot tracks a chase across Europe as Ripley maneuvers his way through an incredible network of lies to evade suspicion and capture. In a way, her story suggests that any one of us might transform from a “normal” person, as Ripley seems to be initially, into a person capable of murder. But her descriptions of Ripley’s malevolence go beyond merely his acting upon self-preservation instincts that lead to murder; her Ripley kills because he wants to be that which he envies, and in his premeditated logic, murder is the solution. There is no doubt of Ripley’s treachery within the novel, no notion that Ripley is more than an emotionally hollow being, no elevation through Highsmith’s literary experimentation that raises the novel into something more than a compellingly told suspense thriller.

In the 1999 film, Ripley gets a more compassionate interpretation with Minghella behind the camera and Matt Damon, in his most intricate and affecting performance, in the title role. Both represent Ripley’s descent into criminality as an ill-fated tragedy rather than the inevitable outcome for a void-of-a-man. Minghella’s adaptation sculpts Ripley into a character plagued by his remoteness, compulsions, and forbidden desires that distance him from others yet feed his desperate longing for companionship. We never view Ripley as a monster ravaging his way through the film, not even during the fateful conclusion that seals Ripley’s plunge into what will eventually become, but not onscreen, a hopeless killer. In Highsmith’s hands, Ripley is an opportunist; in Minghella’s, the character’s complexity is not so easily summed up. Minghella’s The Talented Mr. Ripley is a far more complicated character study, both suspenseful and painful, and its empathy for the protagonist is deeply moving.

When the film opens, Tom Ripley lives in a pitiable basement apartment in New York City. He survives through odd jobs in the realm of bathroom attendant—positions that have him looking up from the bottom, envying the upper class. To cover piano duties at a posh Manhattan party and look the part, he borrows a Princeton University blazer. The Greenleafs, a rich couple in attendance, assume that Tom must know their son, Dickie, a Princeton alumnus. Tom finds himself agreeing to Mr. Greenleaf’s proposition that he travel to Italy for a $1,000 payday to convince their son to return to America. Learning that Dickie loves jazz, Tom researches the jazz greats, albeit unenthusiastically, to make his eventual introduction easier. After his ship arrives at the Italian port, Tom is struck with idle chit-chat from a fellow passenger, the well-heeled Meredith Logue (Cate Blanchett). She asks his name, and by some instinct, he replies: Dickie Greenleaf. This lie is no more calculated than his fib about the Princeton blazer, but already his falsehoods are stacking up.

When Tom arrives in Mongibello (a fictional Italian town), he arranges a chance meeting with the sun-bathing Dickie (Jude Law) and his fiancée Marge Sherwood (Gwyneth Paltrow) on the beach. Dickie writes off not remembering Tom from college because “Princeton is like a fog… America is like a fog.” Before long, Tom has joined Dickie and Marge for lunch, and he learns that the best way to maintain a lie is to confess a little truth in the process. When asked where his talents reside, Tom replies, “Forging signatures. Telling lies. Impersonating practically anybody.” He demonstrates this by mimicking Dickie’s father and confessing Mr. Greenleaf’s scheme in an uncanny impersonation: “Could you ever conceive of going there, Tom, and bringing him back?” he says, playing Dickie’s father in a low, grainy, deliberate voice. “If you would go to Italy and persuade my son to come home, I’d pay you $1,000.” By admitting the purpose of his trip to Dickie through his imitation, he wins over Dickie. He becomes a part of a jealously maintained inner circle, where Tom explores his fascination with Dickie’s greener pasture from within.

Tom makes certain that Dickie learns of his fake love for jazz, and herein begins a friendship of introduction, where Dickie and Marge expose their new naïve American traveler friend to Italy’s many splendors, not the least of which involves Dickie’s fascination with jazz clubs. Tom is swept away by Dickie’s charm, even when he becomes aware of Dickie’s affair with a local woman, Silvana. Together, they travel to Naples to sing at a local jazz club, perform music on stage, and later share an intimate moment playing chess while Dickie bathes. But Dickie moves through friends quickly. Before Tom, there was a local, Fausto, who disappears shortly after Tom arrives. And soon, the bright light of Dickie and Tom’s friendship fades with the arrival of Freddie Miles (Philip Seymour Hoffman) during their trip to Rome. An arrogant, loathsome elitist, Freddie steals Dickie away and turns him against Tom, or at least emphasizes how Tom clings to Dickie and Marge’s Italian getaway. Marge explains, “The thing with Dickie—it’s like the sun shines on you, and it’s glorious. Then he forgets you, and it’s very, very cold.”

Dickie’s final rejection results from Tom’s mounting infatuation, hinted earlier when his eyes linger on Dickie, or in desperate remarks that attempt to affirm the strength of their friendship. Dickie has long suspected Tom and finally confronts him in San Remo by asking if he ever went to Princeton. In Tom’s penultimate maneuver, he admits that he never went to Princeton and did not, initially, enjoy jazz. “I’ve gotten to like it. I’ve gotten to like everything about the way you live. It’s one big love affair.” Dickie does not or chooses not to hear what Minghella’s script calls Tom’s “confession of love.” Without a doubt, Tom is in love, and, at least consciously, Dickie is unaware. Later, scouting for a new apartment in San Remo in a small motorboat, Dickie tells Tom that he wants him to return to America, that he can be a “leech” and “quite boring.” In his final maneuver with Dickie, Tom pours his heart out, confesses his love, but Dickie rejects and insults him. And in the ensuing heated argument, Tom lashes out and strikes Dickie with an oar, an action that surprises even Tom. Dickie launches a retaliation, but now Tom must commit and kills his love in a panicky, tearful slaying. After the scene has calmed, Minghella’s camera from above catches Tom cradling Dickie’s bloodied body before he hides it at the bottom of the Mediterranean.

During the film’s early scenes, Tom seems to surprise himself with his knack for fast-thinking subterfuge. Minghella’s screen story resists confirming Tom’s intentions, whether he always planned on becoming Dickie Greenleaf or if it just happened to Tom’s delight. A curious moment early in the film, before the contrived run-in at the beach, Tom is shown watching Dickie and Marge swimming as he bones up on his Italian. “Questo e la mia faccia… This is my face,” he recites. “Questa e la faccia di Dickie.” Tom does not repeat this line in English but says it with surprise in Italian: This is the face of Dickie. Uncertainty hangs over this scene. Does Tom intend to kill and replace Dickie from the start, or is it more likely that he admires him to the degree of obsession? While the emotional, frantic nature of Dickie’s demise points toward the latter conclusion, Minghella further suggests that Ripley does not know why he wants what he wants—that he does not scheme but instead finds himself scheming and does not understand why. Ripley ultimately wants that which he desires, as any of us do, but what is it that he desires?

Tom is split between what he is and what he wants to be. Though there are no grand embraces or pronouncements, Tom’s sexuality is almost positively gay, but in a setting where being openly gay was not common and was more commonly frowned upon. As an outsider, he desires to be like Dickie, whose so-called normal heterosexuality confuses Tom’s fantasy and also solidifies it, as Tom, being an outcast, wants to be normal too. His sexual identity is brought into question on several occasions within the film, such as when he listens to Chet Baker’s rendition of “My Funny Valentine” but cannot quite tell if a man or woman is singing; perhaps the song’s ambiguity is what draws him to sing his own rendition in a jazz club alongside Dickie. Soon after, he and Dickie’s intimate chess game comes to a sudden end as they discuss being only children in their families. “What does that mean?” Dickie asks. Minghella’s script notes that Tom looks a little too long here and says, “It means we never shared a bath. Can I get in?” The scene ends when Dickie gets up from the bath as Tom, who insists he only wanted to warm up in the bathwater, regards Dickie’s naked body in the mirror until his gaze is caught, and he abruptly looks away.

Certainly, the closeness between Tom and Dickie can be interpreted as brotherly comradeship, though such a reading ignores far too many gradations in Tom. As stated, Minghella’s script makes no bold pronouncements, but remember that Tom is new to deception on this scale; he is learning along the way, and so too, he is new at pursuing his queer desires. Undoubtedly, Tom has never carried out a true gay act, and so his desires remain unclear even to himself. What he knows at this stage is what he feels. As for women, Tom finds they are necessary to blend in, although he never pursues a female romance. During his unfortunate proposal to Dickie in the motorboat, he refers to Marge as “The Marge Problem.” Later, after Dickie is gone, he pretends to confess his love to Marge, if only because she has begun to suspect him. In Rome, Tom’s Dickie has another run-in with Meredith, who has heard rumors of Dickie and Marge’s breakup. Her attractions to Tom’s Dickie are clear, but Tom does not engage—instead, he maneuvers around her and claims he is not yet over Marge. Though Tom could have easily taken advantage of Meredith, there is no need to, and more importantly, he does not want to. Women become his cover of so-called normalcy, whereas Tom’s True Self is gay, his infatuations exclusively male. However, in her books and subsequent interviews, Highsmith has maintained that Tom Ripley is not an overtly sexual being in any respect. If a definition must be given, she claimed it would be bisexual. In his adaptation, Minghella enriches the character by implying that Tom’s sexuality must be suppressed to exist safely, thus making his character’s choice, in the end, devastating and a symptom of a perceived cruel world on a displaced individual.

Tom’s desire is concentrated on that which he cannot be within the identity of Tom Ripley: cultured, wealthy, and socially accepted, though he is anything but. In proposing a relationship with Dickie, he hopes to connect his True Self’s yearnings with his fantasy life of privilege, engaging in an openly gay but cultivated relationship, which, of course, never comes to be. As a result, when Marge introduces Tom to Peter Smith-Kingsley (Jack Davenport), Tom sees another potential meeting of his True Self and his affluent fantasy—one all the more meaningful because Peter, who does not hide his attraction to Tom, will accept Tom as he really is. But in due course, their association leads to the film’s tragic conclusion: After Dickie’s death, Tom’s lies create a series of alibis. He impersonates Dickie in Rome by checking into hotels under Dickie’s name, and he delivers letters from Dickie to Marge that imply their break up. While lying his way through Dickie’s friends and family, and inevitable police investigations, Tom fakes Dickie’s death by forging a suicide note. He kills the suspicious and starkly hetero, thus threatening, Freddie Miles. And he finds himself confronted by Marge, whose paranoia is waved off as grief-ridden hysteria. All loose ends now seem tidy. Tom has escaped with equal parts skill and luck, leaving him with Peter. They have shared several considerable visual exchanges, and their chemistry is on the cusp of a full-fledged love affair in the finale, when he and Peter are together on the ferry to Greece. But then, on the boat, Meredith appears with her family, who know Tom as Dickie from Rome. As he cannot be both Tom and Dickie on the same boat, he chooses the identity that, tragically, would require the least amount of damage control: Dickie Greenleaf.

Earlier, the film shows Tom, in a way, confessing all to Peter, albeit through symbolism better understood by the viewer. “Whatever you do, however terrible, however hurtful, it all makes sense, doesn’t it? In your head. You never meet anybody that thinks they’re a bad person,” Tom admits. Weighed down by guilt, he cannot ignore his bad deeds; they are always with him. He has done terrible things, though he only realizes as much upon reflection. “Don’t you just take the past and put it in a room in the basement, and lock the door, and just never go in there? That’s what I do,” he says. Peter listens, understanding, but not. “And then you meet someone special, and all you want to do is to toss them the key, and say, Open up, step inside—but you can’t, because it’s dark, and there are demons, and if anybody saw how ugly it is…” Tom returns to this “dark basement” metaphor in the film’s conclusion, when he must kill his only hope for true happiness, Peter, to evade being caught in a critical lie with Meredith. “I’m going to be stuck in the basement, aren’t I? Aren’t I? That’s my…” He wants to say curse. “Terrible… Alone, and dark, and I’ve lied about who I am, and where I am, and now no one will ever find me.” Tom’s final descent is as much circumstantial as it is self-propelled. But it’s no less tragic. Minghella brilliantly orchestrates our empathy as Tom, his eyes filled with tears, strangles Peter to death.

Any hope of Tom maintaining some piece of himself is lost in the final scene. With Peter’s death, Tom Ripley dies too; he locks away his identity in the dark basement in this act of self-destruction that leaves only a carefully constructed façade for the outside world. What remains is his regret, from which the viewer is bonded to Tom and which makes The Talented Mr. Ripley a powerful tragedy. Through Minghella’s treatment and Damon’s performance, every crime Tom commits is punctuated with a duality to the character, hinted at by the film’s opening narration: “If I could just go back. If I could rub everything out. Starting with myself. Starting with borrowing a jacket.” But throughout the film, Tom has already begun to wipe out much of his own identity. Consider his love of music. We see it from the first scenes, as Tom is immersed in playing classical piano for an opera singer at the Manhattan party but shows disdain for jazz during his research. Again at the opera in Rome with Meredith, genuine tears stream down Tom’s face at the beauty of the staged production, whereas Tom’s learned love of jazz seems more like a symptom of his love for Dickie. Tom is always at odds with himself; the character is split between impulsive desires and other, more intuitive ones. But the more he lies, the more he destroys his True Self. The character becomes an intriguing case in Minghella and Damon’s hands. However, this interpretation of Tom Ripley as a fragmented, self-destructive psyche has not always been the case in adaptations of Highsmith’s book.

In 1960, French filmmaker René Clément and his co-writer Paul Gégauff adapted her book into Plein Soleil (Purple Noon), a version of the story that begins with Tom and Dickie (here called Philippe) already friends. Clément’s film finds Tom scheming from the start to kill Philippe and steal his identity—a fact which he confesses to Philippe in a cleverly played scene—for motivations fuelled by greed alone, as well as his apparent and eventually consummated attraction to Marge. Clément’s film resolves to be more like Highsmith’s book, following a man who slowly learns the ins and outs of being a cold-blooded career criminal. Although, Clément resists sexual ambiguity in any form and even augments the character into a heterosexual in defiance of Highsmith’s pointed bisexuality. Aside from Minghella using transparent color panes in his title sequence, similar to those in Clément’s film, there are few similarities between the two adaptations. Minghella’s version distinguishes itself because nothing is certain. Tom’s oftentimes confused actions and desires betray him; his impulses force his criminal hand to cover his tracks not out of strategy but as a reaction to his compulsions. At times, he is a compulsive liar; at others, he is an adept strategist. And though Tom may not always know what he is or what he wants to be, he remains fascinating because behind this puzzling identity resides a deeply emotional center.

The Talented Mr. Ripley was the follow-up to Minghella’s The English Patient (1996), which earned Minghella instant acclaim, including an Oscar for Best Direction and a nomination for Best Screenplay. He received another screenplay nomination for The Talented Mr. Ripley, even if the film received less attention on the awards circuit overall. Coming from a universally celebrated romance into a complex, empathetic study of a character who deceives his way through the narrative, Minghella’s reviews were favorable, but less universal. Similarly, its box-office numbers were profitable, but no records were broken. All the same, Minghella’s skill as a director and the production’s polished presentation are undeniable. His transportive mise-en-scène realizes 1950s Italian vistas, glamorous clothes, attractive people, and luscious production values that immerse the viewer in his story. And his treatment of these characters finds richly developed personalities throughout the cast—further brought to life by Minghella’s crew, all of whom reteamed with their director after The English Patient, and again in 2003 for Cold Mountain: cinematographer John Seale, costume designers Ann Roth and Gary Jones, composer Gabriel Yared, and editor Walter Murch.

Minghella also found each cast member at a critical juncture of their respective careers, some immediately before or after their star-making Oscar wins, and others before their celebrity would make them box-office draws. Gwyneth Paltrow was perhaps the most acclaimed of the supporting cast, having won an Oscar the year before for Shakespeare in Love. Cate Blanchett was nominated for Elizabeth the same year and lost to Paltrow, but Minghella expanded the Meredith role to use her evident talent. Jude Law, who won a BAFTA and was nominated for an Oscar for his performance as Dickie, had appeared in virtually unnoticed roles in Gattaca (1997) and David Cronenberg’s eXistenZ (1999). Philip Seymour Hoffman was still years away from winning his Oscar for Capote (2005), although he appeared in P.T. Anderson’s Magnolia in 1999 as well. And Jack Davenport was also several years from his most popular role as Norrington in the Pirates of the Caribbean trilogy. Revisiting the film now, years after these actors have been established among the best performers in modern cinema, only reaffirms the feeling that The Talented Mr. Ripley went underappreciated upon its release.

Even Matt Damon had only just emerged a few years before in terms of star status, having broke out in 1997 with a starring role in Francis Ford Coppola’s The Rainmaker and an Oscar for co-writing Good Will Hunting, followed by roles in Saving Private Ryan (1998), Rounders (1998), and Dogma (1999). Minghella’s film provides what was then and is now Damon’s most multifaceted and daring role. That his performance went without a nomination at the Oscars represents just how out of touch the Academy Awards ceremonies can be in retrospect. For an actor most often associated with box-office successes like the Jason Bourne and Ocean’s trilogies, he injects incredible depth into Tom Ripley. Although it would be easy to see Damon’s performance as a cipher, an outward vacancy is part of the character’s beguiling nature; he preserves a blank slate exterior, boyishness, and inexperience, to absorb the characteristics of others. But through Damon, we can also observe the shattered interior psychology of Tom Ripley. At once, Damon captures his sensitivity and confusion, his vulnerability and duplicity, his ambivalence and desperation. The performance is played with enough subtlety through the highs and lows that cinephiles continue to discuss its nuances and the meaning behind Tom’s intimate scenes with Dickie or Peter.

Though Minghella died in 2008 with only a handful of films to his name, he had already been compared to monumental filmmakers such as David Lean. His capacity to adapt novels into literate yet immeasurably visual motion pictures was demonstrated with each film after The English Patient. However, his dramatic complexity and faith in his audience’s compassion were never greater than in The Talented Mr. Ripley, a film that explores a criminal protagonist through discerning, empathetic eyes. Minghella ends the picture without hope of escape for Tom from his inner darkness; in all likelihood, Tom will continue to murder and lie, and yet, this conclusion leaves us feeling a profound sadness. Minghella creates a beautiful, intricate, and suspenseful story that enhances the thriller dimensions of Highsmith’s novel into a far more significant, emotionally tangled experience. Through Damon’s performance and Minghella’s interpretation, each of Tom Ripley’s lies and murders have an emotional immediacy that becomes crushing in this story of self-destruction, one so convincing, so compelling, that we want to believe Tom’s lies as much as he does. And when Tom’s elaborately constructed fantasy catches up with him, the result is just as heartbreaking for the viewer as it is for the character.

Bibliography:

Bricknell, Timothy (edited by). Minghella on Minghella. Faber & Faber, 2005.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review