The Definitives

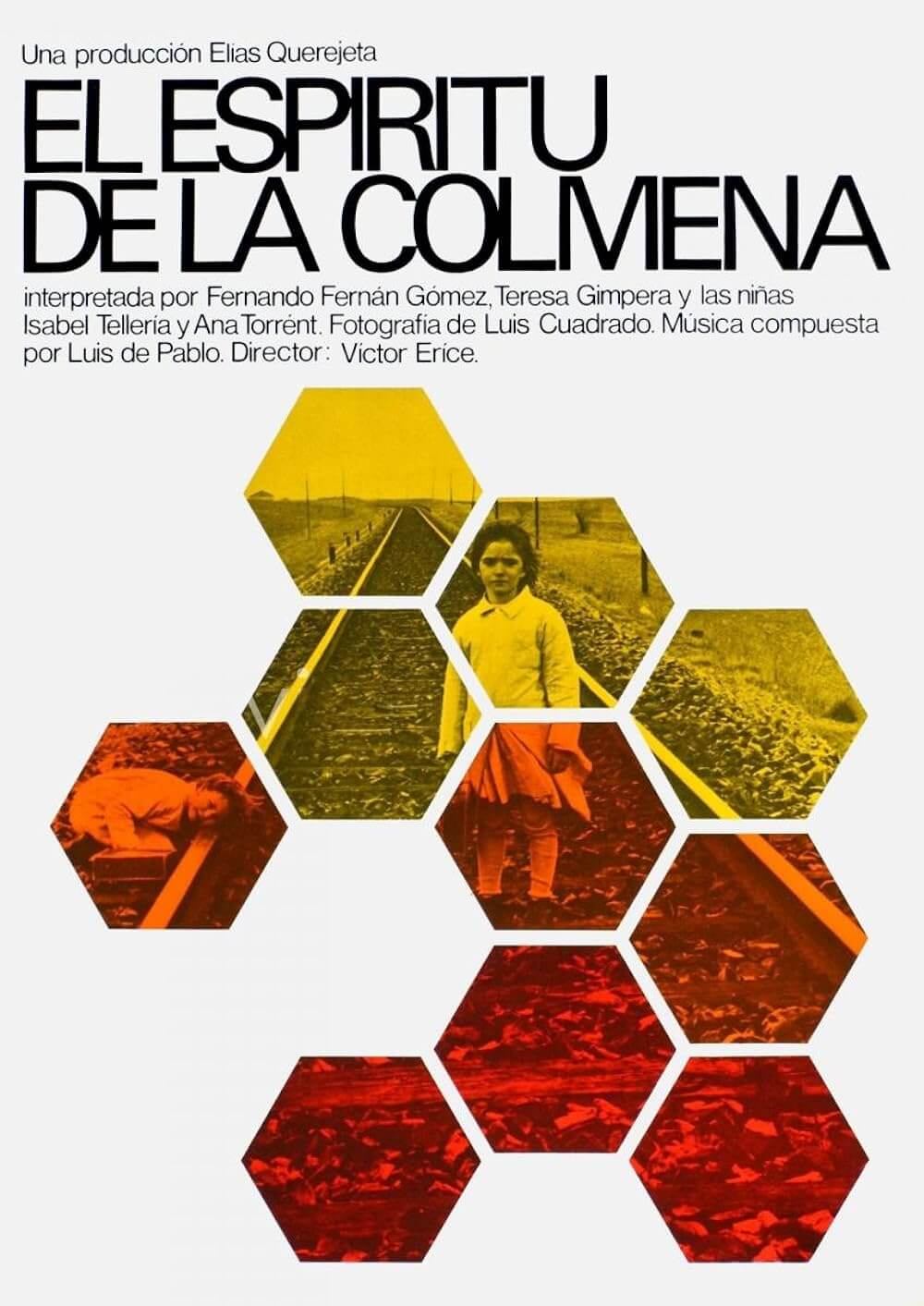

The Spirit of the Beehive

Essay by Brian Eggert |

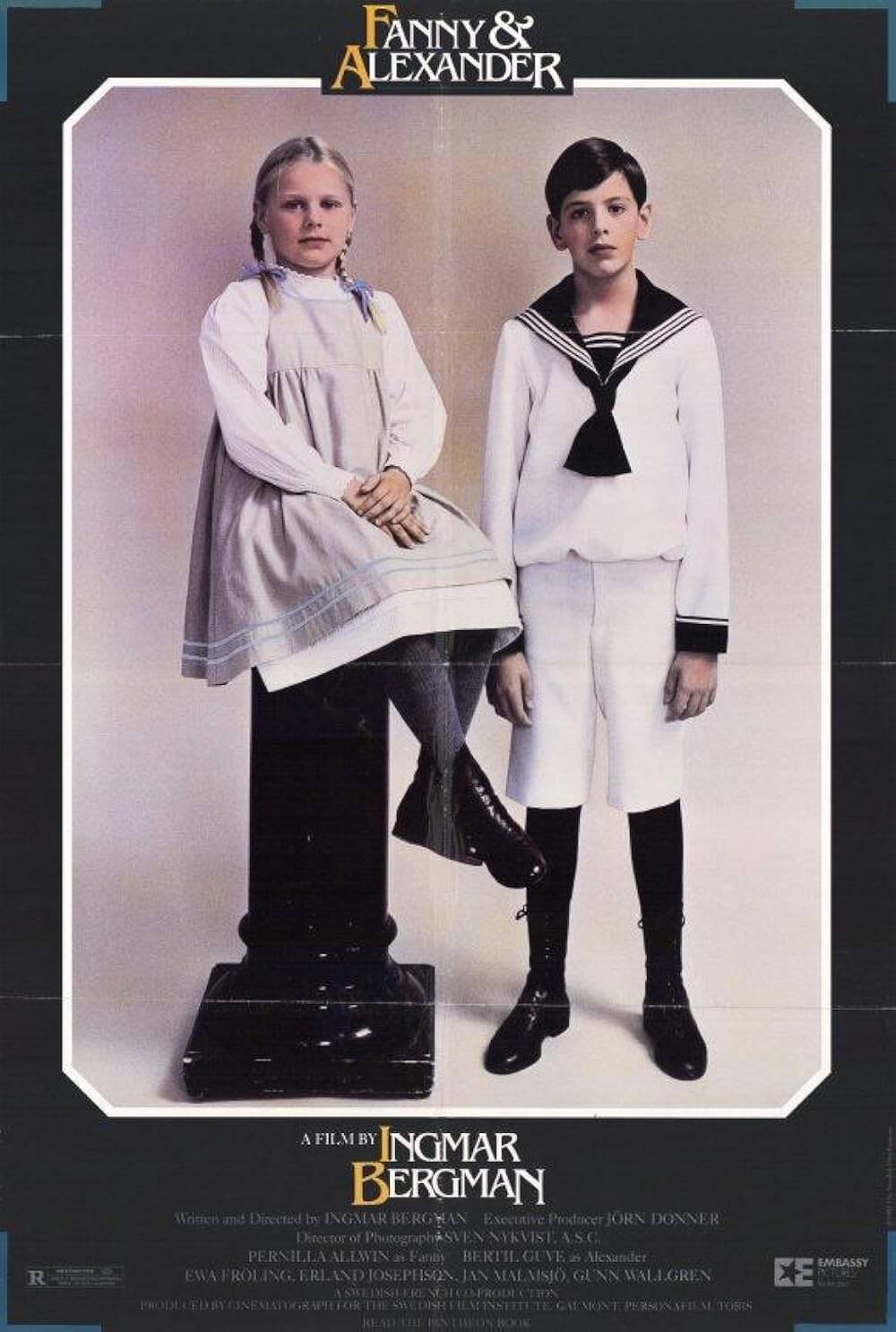

(Note: Published on August 29, 2024, this essay is a newly edited and expanded take on a review, originally published on March 7, 2022, to celebrate the release of Víctor Erice’s new film, Close Your Eyes.)

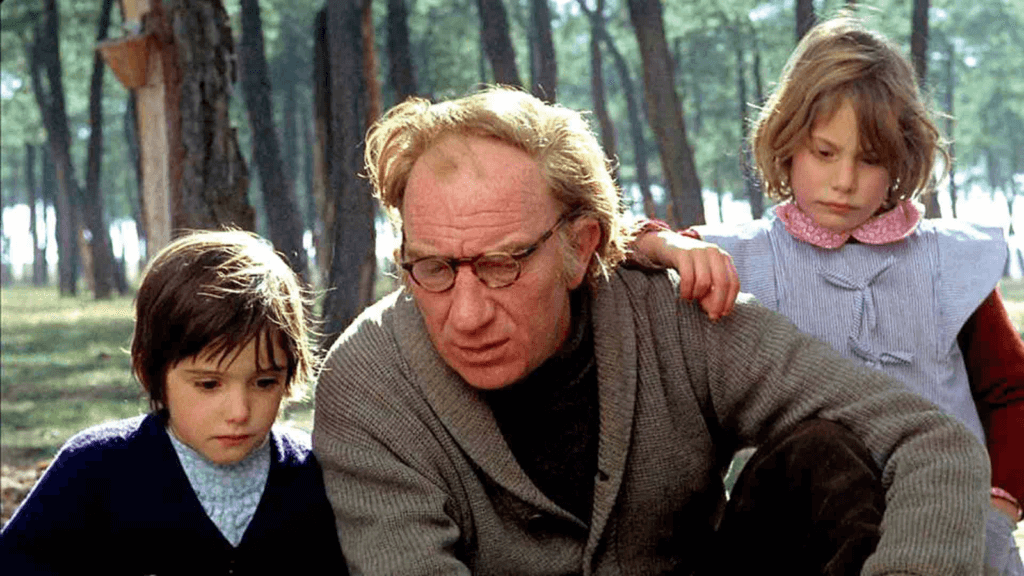

In The Spirit of the Beehive (El espíritu de la colmena), the innocence of a single child becomes an allegory for all of Spain. The story follows six-year-old Ana, whose wide-eyed curiosity and tragic resilience in the aftermath of the Spanish Civil War are conveyed through her vivid imagination, fueled by the power of cinema. Filmmakers have often relied on children to access the purest form of emotions or the truest sense of humanity. However, when juxtaposed against a backdrop of trauma, violence, death, and corruption—and the monsters who create them—a child’s perspective will return the viewer to a time before we learned the many harsh lessons the world teaches, before we made endless moral compromises, and before we accepted or learned to compartmentalize so many awful truths. Writer-director Víctor Erice positions Ana—played by Ana Torrent, who would once again work with Erice in his 2024 return with Close Your Eyes—as a reminder of what people lost during the conflict. He frames the violence and horror through the eyes of a child, which reminds us how to see these truths for what they are. It’s no coincidence when, in a scene in her village’s classroom during an anatomy lesson in which students place organs onto a cutout of a man, a teacher calls on Ana to locate the figure’s eyes. Ana puts the eyes in their spot, allowing the man to see, just as she does for the audience.

The film takes place a year after Francisco Franco took power in 1939. In the context of the screen story, Franco’s Nationalist party had just seized control after defeating the leftist Republic during Spain’s bloody Civil War. Franco would stay in power until his dictatorship ended with his death in 1975, after nearly four decades of oppression, strict patriarchal rule, nationalist Catholicism, and political authoritarianism reshaped the culture. Because Franco understood cinema as a tool to propagate ideas, he also sought to assert social control through censorship, curbing any critiques and instead perpetuating the heroic myth that his regime ended the Civil War. When Erice set out to make The Spirit of the Beehive, he did so in the less intense period at the end of Franco’s rule; however, the Spanish people still lived with the trauma of politicide, repressive policies, and death tolls in the hundreds of thousands. In 1973, when The Spirit of the Beehive debuted at the San Sebastián Film Festival, the dictator’s health was failing him. Many could see Francoist Spain’s time was coming to an end, and audiences welcomed Erice’s critique with more enthusiasm than it might have received a decade earlier. Still, Erice disguised his subversive sociopolitical critique behind deliberately indirect remarks, fooling the strict censorship board that would otherwise quickly remove any clear affronts to the ruling state.

Despite a relatively sparse body of work, Erice has earned a place among Spain’s pantheon of great filmmakers. Born in 1940, Erice studied at the Escuela Oficial de Cinematografía in Madrid. After graduating in 1963, he served as an editor and film critic for the Spanish film journal Nuestro Cine, published between 1961 and 1971, taking its name from a short-lived Marxist film magazine circulated in the mid-1930s. He experimented with several short films before making his debut feature with The Spirit of the Beehive, a stunningly accomplished work that has arguably overshadowed his career. Much of his output to follow consists of documentary shorts, segments in anthology films, and experimental works, such as his 1992 documentary-fiction hybrid, The Quince Tree Sun, a meditation on creation and time through the lens of painter Antonio López García. Accessible but also shaped by an arthouse aesthetic, Erice’s films are mysterious, beautiful, haunting, understated, and contemplative. They dwell on the intersection of perception and memory as they collide with art, family, history, and politics, exploring the many folds and equivocations of the human experience. This is why Erice’s use of time has been crucial in understanding his approach. His typically long sequences use shots not to make a direct point but to dwell on the fluctuations that occur over time.

Similarly, The Spirit of the Beehive conveys the requisite interiority of its oppressed characters through the fragmentation of and isolation in their world, shown in subtle but readable symbolic imagery. Even though Erice’s aesthetic might be called minimalist and restrained—even transcendentalist—he uses this style to create a sharp contrast to Spain’s popular and weightless comedies of the time. Broad films like Pedro Lazaga’s La ciudad no es para mí (The City is Not for Me, 1966), about a country father who visits his son in the big city, became top box-office earners. Whether they were empty comedies or outright state-sanctioned productions designed to present a unified front to the world, Spanish cinema at the time was radically different from Erice’s film. The Spirit of the Beehive occupies a European aesthetic, often attributed to Michelangelo Antonioni, which employs time and space to symbolic effect. The film unfolds in a series of protracted shots, and the camera rarely makes expressive movements. Long passages develop without dialogue, leaving the director’s critique far from a stated condemnation of Francoist ideology. Instead, the viewer must discover the film’s themes through a process of reading and interpretation; otherwise, they might miss Erice’s remarks on Franco without placing the film in its extratextual framework.

Just as filmmakers use children to stand for a part of the whole, they also use history and fantasy to comment on the present. The Spirit of the Beehive remains unique for 1973 not only because it situates the story at the beginning of Franco’s takeover but because Erice uses fantasy imagery from James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931) in powerful terms. The story follows Ana and her slightly older sister, Isabel (Isabel Tellería), who live in Hoyuelos, a Castilian village. These are ordinary girls who skip, pillow fight, and share secrets; however, an air of death and political turmoil surrounds them. Early scenes show the sisters watching Frankenstein inside an impromptu cinema. Transfixed, Ana finds her mind flooded with images and ideas. In particular, she thinks about the scene involving Frankenstein’s monster and the young girl, where the confused monster tosses her into the lake like one of her flowers. “Why did he kill her?” Ana asks her sister. Isabel replies that she will explain later, and that night, she proceeds to tell Ana that the monster is the spirit of a man. To see it again, they can search for it near an abandoned farmhouse, or Ana can close her eyes and say her name. The spirit’s rules, as Isabel describes them, have little order, allowing Ana’s young mind to freely explore their boundaries.

Erice shows Ana’s belief through a combination of dreams and reality. Isabel’s stories about Frankenstein’s monster shake Ana so much that she must search out the spirit, regardless of her fear. When she goes searching and finds a republican soldier in a farmhouse, wounded and hiding, it’s almost as though Ana has conjured his spirit from her dreams. Though she is afraid, Ana helps the soldier by offering him an apple and dressing his wound. Inevitably, Francoists locate the soldier and shoot him on the spot. But Ana continues to search for the spirit, convinced that he will take another form. One night, she goes searching for him and, again, conjures the spirit from her mind; this time, it resembles Frankenstein’s monster—a convincing and haunting recreation of Boris Karloff in makeup as the Creature. He approaches her near a shore. Trembling, Ana closes her eyes, afraid that the Creature might repeat the scene from Whale’s film and kill her. But she identifies with the monster, and he embraces her. Scholar John Hopewell suggests that Ana seeks the spirit to replace her father, Fernando (Fernando Fernán Gómez), who spends most of his time in his study reading, listening to his shortwave radio, tending to his beehives, or losing himself in thought. “Come out of the clouds,” someone tells him. Ana takes after her father; their minds are always elsewhere.

There’s a point in everyone’s childhood where they stop believing in the imaginary, from Santa Claus to the Boogeyman. Although The Spirit of the Beehive focuses on Ana’s perspective, it’s worth noting that Isabel has stopped believing. She lies and tells her sister stories, encouraging Ana’s fixation on Frankenstein and the spirit, which sets the foundation for Ana’s later visions—even though she believes “everything in a movie is a lie.” Isabel has already become cynical, even violent. In one scene, she strangles a cat. “What’s wrong with you?” she asks the cat when it scratches her to escape. Then, she uses blood from the wound for makeshift lipstick. Later, Isabel lies motionless on the ground, playing a cruel trick on her sister. It’s unclear whether seeing the Civil War has given Isabel macabre ideas or if she’s just naturally morbid. Nevertheless, each family member seems to be in their own little world. Take Teresa (Teresa Gimpera), their mother, who avoids her husband and looks preoccupied throughout the film. Early on, she mails a letter to a far-away lover in a postal box at a train station, and she watches as the solemn faces of men look out from the passenger car’s window. The details about her affair never emerge. Erice depicts characters marked by interiority and alienation from the war, but he only shows us projections from Ana’s mind.

Erice aligns the film’s aesthetic with Ana’s subjectivity to address the political conditions under which Erice made The Spirit of the Beehive, adopting a mode of ambiguity that requires interpretation, which naturally aligns with Ana’s worldview. As a child, she cannot make sense of the world and fills in the blanks with her own mythology of spirits. Accordingly, Erice floats from one image to the next, not necessarily in a shot-to-shot narrative logic, but in a series of dreamy transitions loaded with potential meaning. For instance, the director seems to transition from Ana dreaming to the next morning, when the republican soldier appears out of nowhere, reinforcing Ana’s impression that her thoughts about the spirit made the soldier materialize. This dreamlike perspective, shot in honey hues during magic hour by cinematographer Luis Cuadrado, contrasts Erice’s setting in a world marked by real conflicts. Peripherally, Erice offers scenes of Ana’s family members—each isolated from one another in separate shots and rarely, if ever, seen together—to remind us that the film takes place in a reality that Ana escapes in her imagination.

Erice’s blend of reality and fantasy was highly influential, supplying filmmakers such as Guillermo del Toro with a blueprint. Del Toro’s The Devil’s Backbone (2001) and Pan’s Labyrinth (2006), particularly the latter, follow Erice’s schematic: a child in the Spanish Civil War processes reality by losing themselves in fantasy. The Mexican auteur differentiates himself by employing genuine fantasy elements, ranging from ghosts to mythical creatures, instilling uncertainty about whether they are projections of his characters or actually inhabiting their films’ worlds. Ever fascinated with the humanity of monsters and driven by his empathy for them—the title of his traveling cabinet of curiosities, dubbed At Home with Monsters, says it all—Del Toro often embraces the fantastical as reality. (It’s no wonder that Del Toro has made an adaptation of Mary Shelley’s novel.) Del Toro would inspire Spanish filmmakers such as J.A. Bayona, whose similarly themed A Monster Calls (2016) grapples with childhood trauma through the guise of a kindly ent-like tree monster. By contrast, Erice never hints that Ana’s dreams and visions of Frankenstein’s monster could be real; instead, he situates the film in the real world and uses the notion of a spirit to raise questions. Monsters are, by their nature, unknowable aberrations, sites of the inhuman, unfamiliar, deviant, and different. Ana lives in a world of monsters that she cannot yet understand, and her interest in the macabre represents an escape from, or perhaps even normalization of, the horrors in her mind.

Childhood has often been linked to national identity in Spanish cinema, symbolizing the country’s collective memory and the suppressed or repressed traumas experienced among adults. Scholar Jessica Balanzategui observes this is partly because Franco sought to influence children with cinematic propaganda, seeing them as “a particularly vulnerable and precarious sociopolitical unit that must be carefully moulded for the successful advancement of Spanish society.” Franco’s attempts to shape the minds of young Spanish children emphasized their vulnerability but also made their fragility central to themes of national identity. As a result, the child is at stake in Spanish cinema, subject to national trauma beyond the twentieth century’s Freudian links between childhood trauma and its impact in adulthood. In addition to Del Toro, titles such as Jaume Balageuró’s The Nameless (1999) and Bayona’s The Orphanage (2007) are shaped by decades of Spanish history, from the traumas of the Civil War to Francoism. The scars sometimes materialize in the form of ghosts and apparitions; sometimes, with violent consequences, as in Narciso Ibáñez Serrador’s Who Can Kill a Child? (1976), about an English couple who visit a Spanish island to find its inhabitants are maniacal children. Elsewhere, Pedro Almodóvar dwells on childhood as a psychological marker for his characters in many films, including Talk to Her (2002), Bad Education (2004), Volver (2006), and Pain and Glory (2019).

How appropriate, then, that Ana sees the cinematic Frankenstein’s monster of all things. More than Shelley’s literary take on the Promethean myth, Boris Karloff’s rectangle-headed, stiff-walking Creature remains an iconic image passed down from Whale’s Frankenstein and the superior Bride of Frankenstein (1935), along with the best-forgotten Son of Frankenstein (1939). Erice repurposes the image of Karloff’s maligned creation, strung together from dead body parts by a mad scientist, and therein reflects the existential trauma permeating postwar Spain. The Creature is a symbol of the metaphorical monster created by Francoism through its dehumanization of its enemies and those who carry out its wartime atrocities. But it also evokes, as scholar Dominique Russell observes, the wounded soldiers who returned home with post-traumatic stress disorder and sauntered through life like the living dead. The Creature is not a purely evil presence; rather, it inhabits a space between good and evil, driven toward the former but mangled and given to impulses by the latter—as evidenced by the flower scene and drowning in Frankenstein. The monster is an unclassifiable entity onto which both Ana and the viewer, who has more historical perspective, can project meaning.

Erice recognizes this and embraces the ambiguity, allowing the Creature to embody one of the many iterations of his title’s “spirit,” which takes multiple forms: the wounded republican soldier, Isabel’s twisted behavior, and the anatomical cutout of a man. Despite the imagery borrowed from Frankenstein, Ana may also associate her father, Fernando, with the spirit. Early in the film, when first watching Frankenstein, Erice cross-cuts between the film and Fernando working in his bee-keeping outfit, an image that would look frightening to most children Ana’s age. Perhaps Ana is unknowingly haunted by Fernando, hearing his footsteps later when she attempts to conjure the spirit. Fernando’s presence also haunts Teresa, who sleeps while Fernando’s shadow projects on the bedroom wall behind her, his presence a violation and unwelcome, serving as a reminder of her situational security yet also her feeling of imprisonment. The sheer pluralism of the spirit in its many forms underscores how the Creature does not occupy a singular meaning of good or evil, the powerful or the powerless, the healing and the horrific. It lingers on the margins of the known, singular only in its refusal to occupy a rigid definition.

In Francoist Spain’s world of absolutes, structured around severe borders and ideological dogma, Erice’s spirit at once inhabits that world and resides outside of its reach. The spirit is a symbol of the characters’ desire to escape Francoism, a sense of being held hostage in a homeland where a fleeting government imposes its strictures. Erice shows his characters yearning to be free of their veritable imprisonment at various points in the film. When Fernando listens to a short-wave radio, he’s hoping for news outside of state-sanctioned bulletins. After mailing her letter, Teresa longingly watches a train leaving the station, perhaps wishing she, too, could depart. The fugitive republican soldier attempts to escape and ends up dead for betraying his government. Everyone is trapped in the hive. And while the spirit inhabits this realm, it also passes through the borders that restrict other characters, embodying a product of that world while also reflecting its cruelty. The spirit and the hive it inhabits, like so many aspects of The Spirit of the Beehive, are contradictory, multifaceted, and unresolved. Indeed, Erice drew the title from The Life of the Bee, a 1901 book by French author Maurice Maeterlinck, who writes about the “spirit of the hive” as a force at odds with itself, sovereign yet humbly obedient to laws of its making, dangerous yet capable of creating honey and helping ecosystems thrive.

The Spirit of the Beehive uses its titular figure to indicate something wrong, and upon its release, Francoist critics considered this social critique blatant. But Erice’s artistry and restraint avoid the more obvious signs that another Spanish filmmaker, such as iconoclast Luis Buñuel, would employ to send up Francoist ideology in Viridiana (1961). Erice’s methods and uses of symbolism throughout prove readable yet deemphasized by his obfuscatory treatment of mood and image. For that reason, time has been kind to The Spirit of the Beehive. Aside from a flute score by Luis de Pablo, it feels ageless and no less powerful. Its symbolism has led to countless other interpretations beyond what Erice intended. For example, Virginia Higginbotham believed that the Creature represents Spain in a “ghoulish collage, a monstrous figure constructed by a sinister creator whose name sounds very much like Franco.” More convincing is scholar Linda Ehrlich’s argument that children in the film “could be seen as paradigms for the visionary and alienated artist,” which assumes Erice’s role as a self-reflective artist. Perhaps Erice, who only made a few short films and two more dramatic features in his lifetime—including El Sur (1983) and Close Your Eyes—saw himself in Ana. Doubtless, becoming a filmmaker in Franco’s Spain left Erice feeling inhibited yet searching for answers.

The Spirit of the Beehive is one of the greatest films about children’s pliable yet open minds. For all its humanity, formal austerity, and absolute beauty, its political message reinforces cinema’s reach. Note how the scene where Fernando examines the dead soldier’s body in the same room where Ana watched Frankenstein suggests that films might be a form of cultural triage. While The Spirit of the Beehive’s direct political remarks might feel less potent today—after so much time has passed since Francoism and amid the generally overstated tenor of contemporary cinema—what endures are lingering ideas about how cinema ignites the imagination and engages the mind. From the moment Ana sees Frankenstein, she is scarred. Erice’s point isn’t as simple as equating the monster with Franco. Rather, he examines the mind’s frailty and cinema’s capacity to change it. The film acknowledges the damage that monsters can do, but it also demonstrates that, when used in an expressive format such as cinema, monsters can function as prompts to raise questions of both national and personal identity. When Ana opens her bedroom window with its honeycomb design in the final scene and announces, “Soy Ana” (“It’s me, Ana”), it’s a statement of declaration and invitation. Ana has seen the monster and comes to know herself better for it. In a sense, the film reveals the necessity of monsters. When they appear in life or cinema, they present a platform against which we can better know ourselves.

Bibliography:

Balanzategui, Jessica. “The Child and Spanish Historical Trauma.” The Uncanny Child in Transnational Cinema: Ghosts of Futurity at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century, Amsterdam University Press, 2018, pp. 95–120. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv80cc7v.7. Accessed 15 September 2021.

Edwards, Gwynne. Indecent Exposures: Buñuel, Saura, Erice & Almodóvar. Marion Boyars Publishers Ltd, 1995.

Ehrlich, Linda C. An Open Window: The Cinema of Victor Erice. Scarecrow Press, 2000.

—. “The Name of the Child: Cinema as Social Critique.” Film Criticism, vol. 14, no. 2, Allegheny College, 1990, pp. 12–23, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44075844. Accessed 15 September 2021.

Higginbotham, Virginia. Spanish Film Under Franco. Austin: U of Texas P, 1988.

Hopewell, John. Out of the Past: Spanish Cinema after Franco. British Film Institute, 1986.

Russell, Dominique. “Monstrous Ambiguities: Víctor Erice’s ‘El Espíritu de La Colmena.’” Anales de La Literatura Española Contemporánea, vol. 32, no. 1, Society of Spanish & Spanish-American Studies, 2007, pp. 179–203, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27742469. Accessed 15 September 2021.

Smith, Julia. “The Spirit of the Beehive: Spanish Lessons.” Criterion.com, 18 September 2006. https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/447-the-spirit-of-the-beehive-spanish-lessons. Accessed 15 September 2021.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review