The Definitives

The Skin I Live In (2011)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

(Note: This essay was originally posted exclusively to Patreon in February 2022.)

Pedro Almodóvar’s career has been about transitions. Over the last 40 years, he has fluctuated from the renegade whose camp and transgressive sensationalism imagined a Franco-less Spain, as in Labyrinth of Passion (1982), to a mature filmmaker who openly confronts his country’s tragic national history, as in Parallel Mothers (2021). The director has dabbled in seductive and darkly comic tales about killers (Matador, 1986), psychopathic kidnappers (Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!, 1990), and rapists (Kika, 1993). But he also has a penchant for satire (Dark Habits, 1983) and screwball comedy (Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, 1988). Throughout his varied career, Almodóvar has centered his queer male gaze on women, whom he portrays with as much depth and sensitivity as Ingmar Bergman or Woody Allen. And to whatever degree Almodóvar’s fluctuation through an array of genres might be seen as metachrosis, the director’s touches remain unmistakable. Every Almodóvar film, whether it’s a sex comedy meant to liberate his audience or a sobering drama about unearthing the past, bears his signature. Even so, there’s never been another Almodóvar film quite like The Skin I Live In, a complex thriller that, much like the filmmaker’s career, transitions from one kind of movie to another, shifting the audience’s sympathies in unexpected and challenging ways.

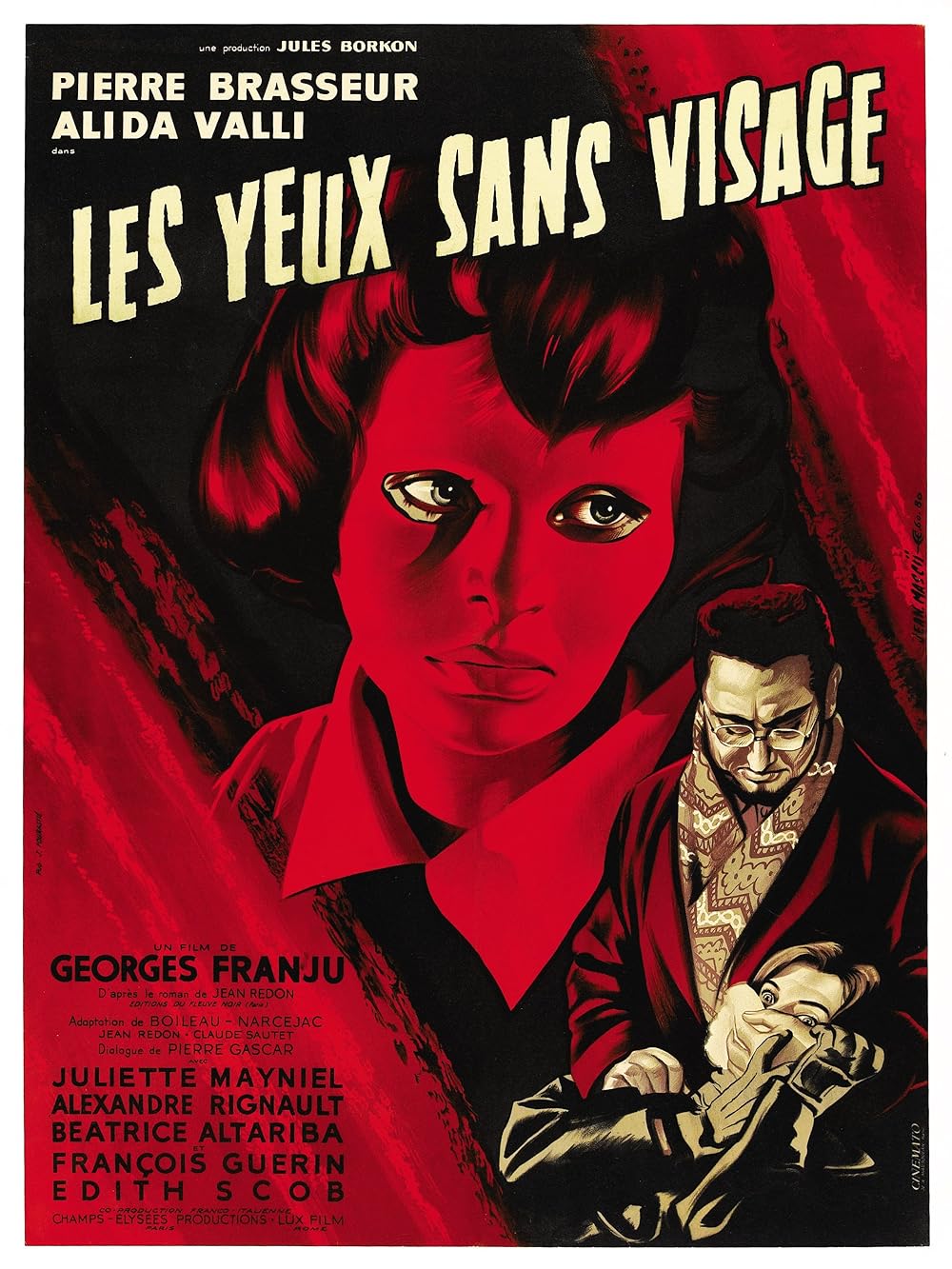

Officially, Almodóvar based The Skin I Live In on French author Thierry Jonquet’s novel Tarantula, a book published in 1984 just as notions of transgender identity and sex reassignment surgery had started to be discussed by mainstream culture. But both Jonquet and the Spanish director owe a debt to French filmmaker Georges Franju’s horror masterpiece, Eyes Without a Face (1960). All three texts involve talented surgeons carrying out medical procedures to transform their respective victims into replacements for their disfigured or dead daughters. Dr. Génessier in Franju’s film evokes sympathy from the viewer as an obsessed father who desperately tries to restore his living daughter’s face after an accident he caused. In Tarantula, and by extension Almodóvar’s film—his second, after Live Flesh (1997), not based on an original idea—the surgeon hopes to replace his daughter by carrying out a series of operations on her rapist. A curious blend of horror and medical science subsists beneath the surface of Almodóvar’s film, which leaps between genres. Along with thematic influence from Mary Shelley and George Bernard Shaw, the film slithers between a kidnapping yarn, erotic thriller, revenge story, and body horror.

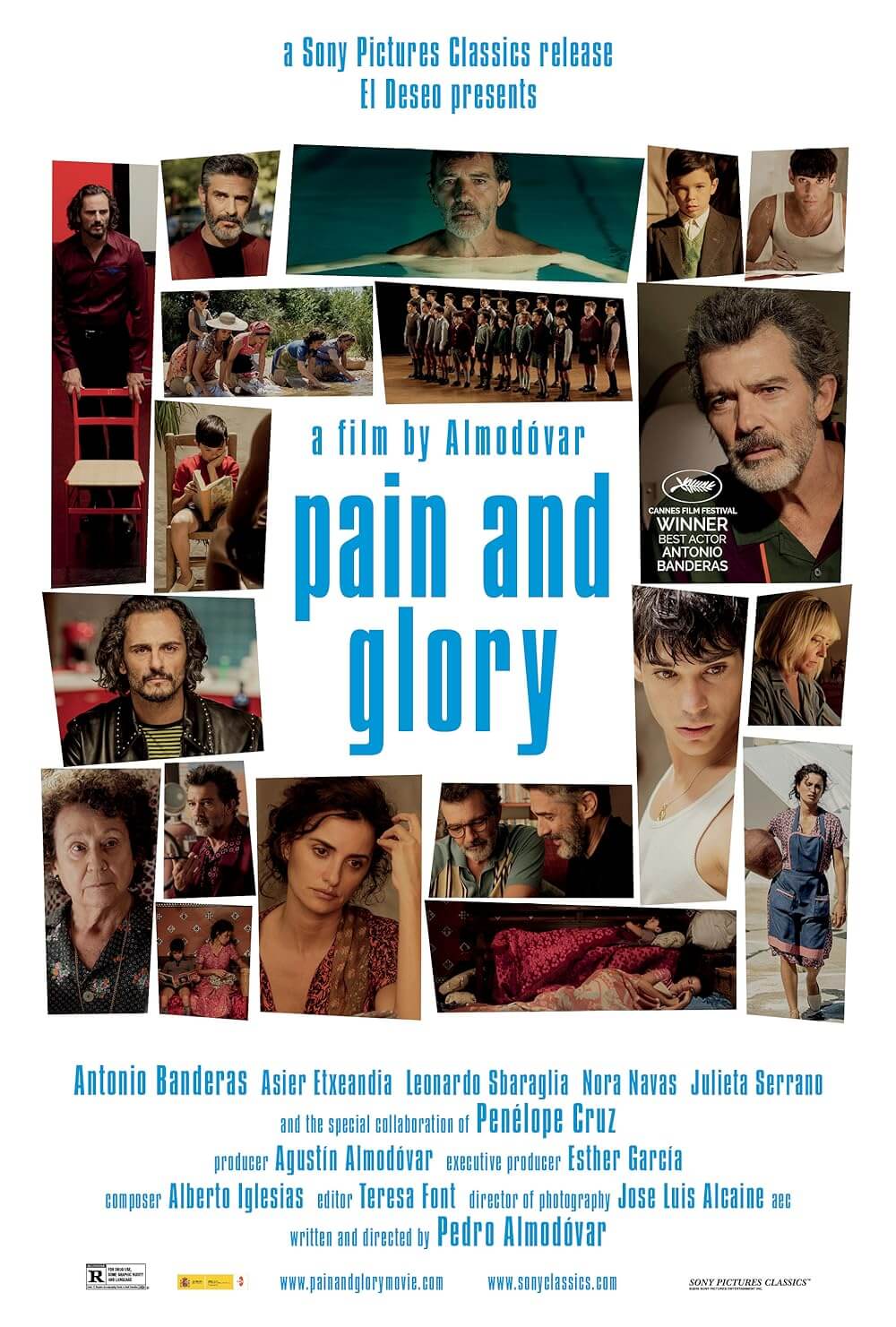

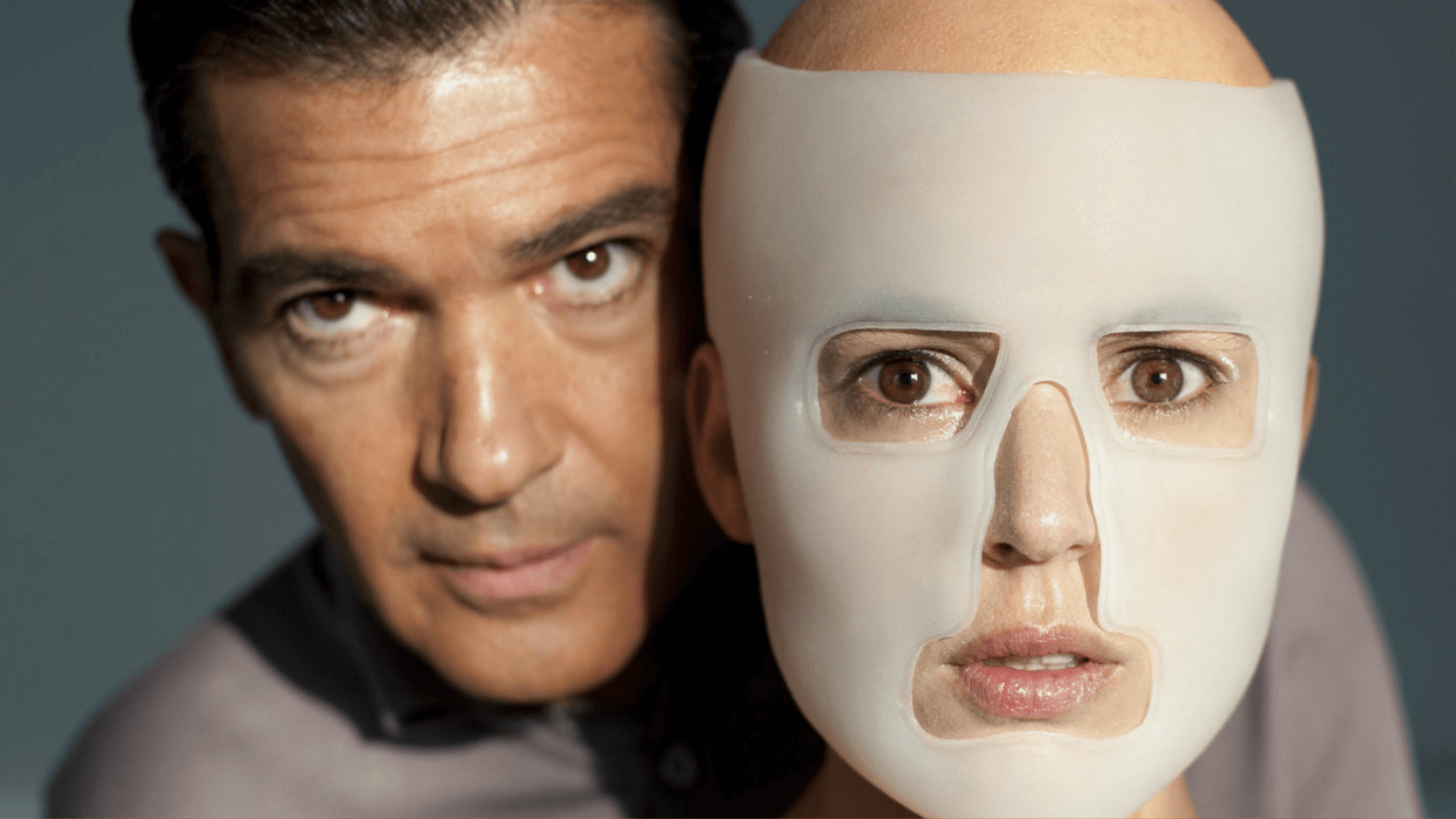

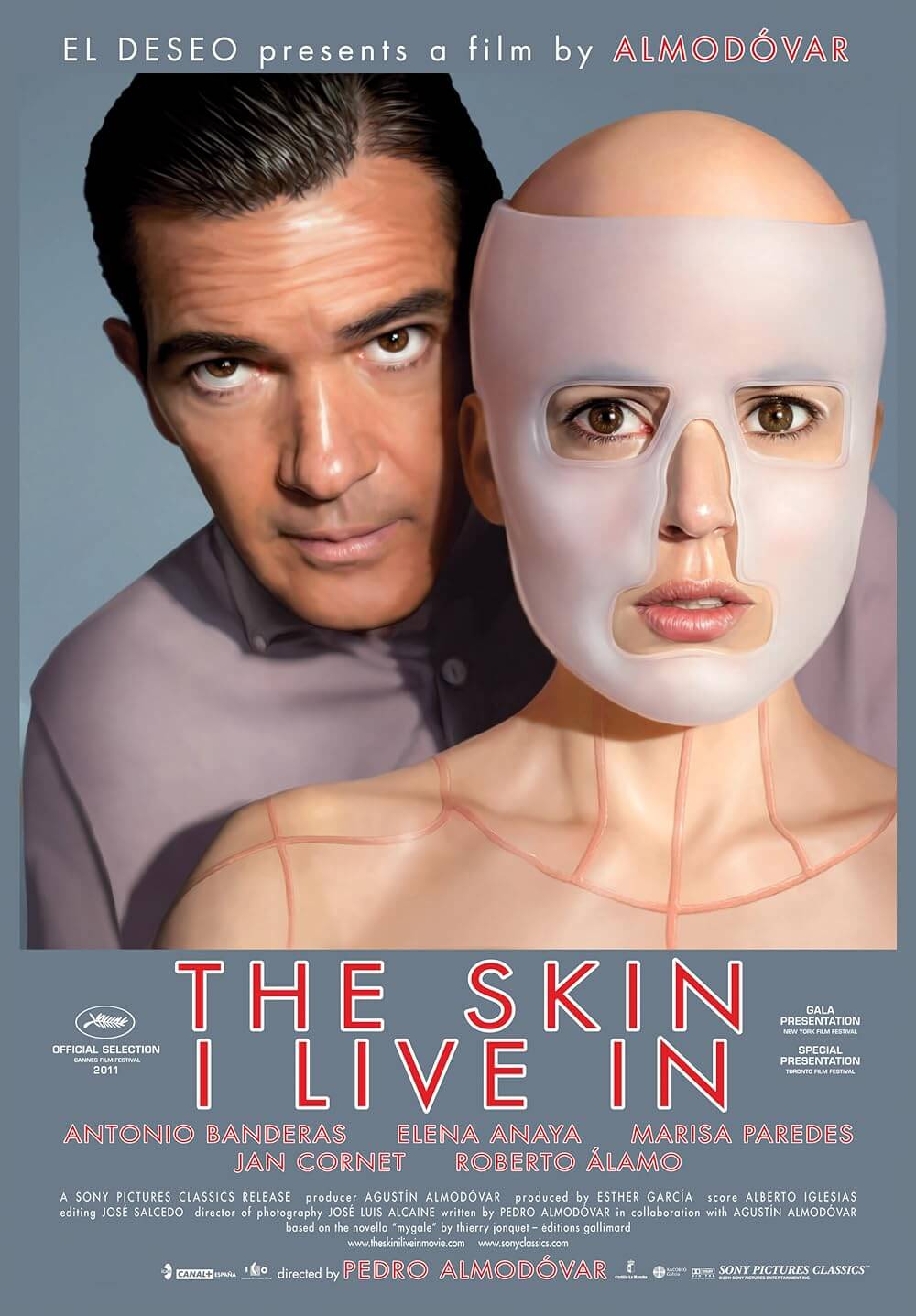

The film reunites Almodóvar with Antonio Banderas. Their previous collaboration 20 years earlier was Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!, where Banderas played an obsessive lunatic who kidnaps a former porn star and, in a flourish only this director could pull off, the two fall in love. The Skin I Live In crafts a similar scenario. Banderas gives one of his best performances as another kidnapper of sorts, and his character falls for his victim once more. But Almodóvar’s sensibilities have changed from the John Waters-style exaggeration of his ’80s work, and Banderas wasn’t around for the transition. The Málaga-born actor left Spain for Hollywood in the early 1990s, performing in an over-the-top, commercial expressivity seen in Desperado (1995), Assassins (1995), and The Mask of Zorro (1998). “Pedro wanted me to develop the character through economy of interpretation,” Banderas told New York magazine, “to make him a kind of minimalist object, which clashed with my natural animal tendencies.” The result is something Banderas had never done at that point—an interior character who, not unlike his victim, wears a mask. Though, his mask consists of clinical superiority and coolly rendered abuses of power. The actor has only been better in Almodóvar’s later Pain and Glory (2019).

The film reunites Almodóvar with Antonio Banderas. Their previous collaboration 20 years earlier was Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!, where Banderas played an obsessive lunatic who kidnaps a former porn star and, in a flourish only this director could pull off, the two fall in love. The Skin I Live In crafts a similar scenario. Banderas gives one of his best performances as another kidnapper of sorts, and his character falls for his victim once more. But Almodóvar’s sensibilities have changed from the John Waters-style exaggeration of his ’80s work, and Banderas wasn’t around for the transition. The Málaga-born actor left Spain for Hollywood in the early 1990s, performing in an over-the-top, commercial expressivity seen in Desperado (1995), Assassins (1995), and The Mask of Zorro (1998). “Pedro wanted me to develop the character through economy of interpretation,” Banderas told New York magazine, “to make him a kind of minimalist object, which clashed with my natural animal tendencies.” The result is something Banderas had never done at that point—an interior character who, not unlike his victim, wears a mask. Though, his mask consists of clinical superiority and coolly rendered abuses of power. The actor has only been better in Almodóvar’s later Pain and Glory (2019).

Reigniting their trusted collaboration, the director molds his actor into a methodical scientist and vengeful father. Banderas plays Robert Ledgard, a respected surgeon with a secluded villa in Toledo. But surfaces always give way to something more entrenched and psychological in Almodóvar’s cinema, and beneath Robert’s façade is a merciless Dr. Frankenstein. Having lost his wife in a fiery car crash that left her entire body scarred, prompting her to commit suicide, Robert hopes to prove that splicing pig and human flesh will supply a durable, even fire-resistant alternative. So he performs illegal procedures in his private lab, testing his radical transgenic technique. He experiments on a beautiful patient (Elena Anaya), keeping her inside an antiseptic bedroom in his house. Trapped in a room with barred windows and locked doors, supposedly for her protection, the patient must wear a skin-color compression suit. She passes her days with yoga and the art of French feminist sculptor Louise Bourgeois, sculpting her own contorted figures reminiscent of Bourgeois’ art to reconcile her changing physical identity. Meanwhile, Robert watches her on a massive monitor in his bedroom next door, like a window into the next room, proud, enamored, and obsessed.

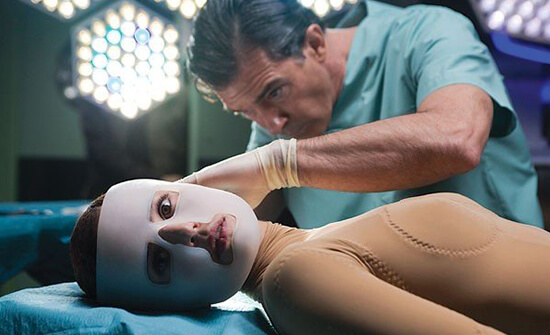

As usual, Almodóvar informs every detail of The Skin I Live In. Production designer Antxón Gómez, art director Carlos Bodelón, and set decorator Vicent Díaz create geometric, clinical spaces of controlled grays, accented by vivid paintings with fleshy colors and curves. Robert’s home looks as though his interior decorator tried to offset a doctor’s office aesthetic with corporeal figures and splashes of color. Later, the chilly modernist design gives way to crimson sprays of blood across bed sheets, chaotic and unhinged in the manner of Jackson Pollack. Fine art is everywhere, as ever in Almodóvar’s films. Note how Robert’s patient reclines on a sofa like Ingres’ Grande Odalisque, the curvatures of her torso and hips creating an alluring and painterly shape. The image is echoed by Robert’s enormous paintings by Guillermo Pérez Villalta and Titian, depicting women reclining on a divan in the same classical posture, as a source of masculine desire. In a nod to Franju, Almodóvar shows us how Robert rebuilt his patient with the help of a semi-transparent plastic mask that stabilizes her face—a haunting evocation of Edith Scob from Eyes Without a Face, albeit less doll-like. Scob’s character has an aloof, ethereal quality. Robert’s patient feels urgent and trapped. Yet, she is so precious to Robert as a medical subject, a deeply disturbing object of desire, and a site of revenge.

In true Almodóvar fashion, the film’s pulpy first half spirals in unpredictable ways. The initial assumption is that Robert has somehow kept his wife alive but isolated because his genetic experiments are illegal, and that their marriage has since soured. But the details remain unclarified at first. Enter the hulking Zeca (Roberto Álamo), the other illegitimate son of Robert’s live-in mother and housekeeper, Marilia (Marisa Paredes). He arrives after a robbery, donning a full tiger getup for Carnival as a disguise, insisting that his mother hides him. While inside, Zeca spots the imprisoned patient on a monitor and recognizes her as Gal, Robert’s supposedly dead wife. Zeca and Gal had once planned to run away together, but the fiery crash they were both involved in left her nearly dead. Zeca breaks down the patient’s door and ravages her—a disturbingly animalistic scene—until Robert appears and shoots him dead. After disposing of the evidence, Robert and his patient share a bed and dream of their respective pasts. The plot maneuvers through time with fluid ease, flashing back and then returning to the futuristic present of 2012. It’s a structure that rewards additional viewings and amounts to a brilliant piece of narrative gamesmanship on Almodóvar’s part, changing how his audience feels about the characters.

In true Almodóvar fashion, the film’s pulpy first half spirals in unpredictable ways. The initial assumption is that Robert has somehow kept his wife alive but isolated because his genetic experiments are illegal, and that their marriage has since soured. But the details remain unclarified at first. Enter the hulking Zeca (Roberto Álamo), the other illegitimate son of Robert’s live-in mother and housekeeper, Marilia (Marisa Paredes). He arrives after a robbery, donning a full tiger getup for Carnival as a disguise, insisting that his mother hides him. While inside, Zeca spots the imprisoned patient on a monitor and recognizes her as Gal, Robert’s supposedly dead wife. Zeca and Gal had once planned to run away together, but the fiery crash they were both involved in left her nearly dead. Zeca breaks down the patient’s door and ravages her—a disturbingly animalistic scene—until Robert appears and shoots him dead. After disposing of the evidence, Robert and his patient share a bed and dream of their respective pasts. The plot maneuvers through time with fluid ease, flashing back and then returning to the futuristic present of 2012. It’s a structure that rewards additional viewings and amounts to a brilliant piece of narrative gamesmanship on Almodóvar’s part, changing how his audience feels about the characters.

Take Robert, who has much in common with Dr. Génessier, the mad scientist from Eyes Without a Face. Both have been marked by tragedy and driven to prevent anything like that from happening again. For Robert, Gal’s suicide mirrors the suicide of his daughter, the socially anxious Norma (Blanca Súarez). Robert’s flashback reveals that he took her to a posh party, where Vicente (Jan Cornet), a budding artist on ecstasy, raped her. The incident worsens Norma’s condition and eventually compels her to leap to her death out of a hospital window. Robert learns about what transpired and, with nothing left but his work, resolves to carry out a twisted scheme. He captures Vicente and keeps him in a dungeonlike subbasement. Before long, Robert drugs Vicente and carries out one surgery after another. He starts by removing Vicente’s penis to craft an artificial vagina in its place, demanding that Vicente use a series of dilators to expand the new orifice for intercourse. He gives Vicente a face that resembles, all too closely, his dead wife Gal, along with feminine features (smooth skin, breasts, round hips). He even gives Vicente an ironic new name: Vera (“true” in Latin). What begins as an extreme form of poetic justice unfolds over six years, during which Vicente convinces himself to become Vera and even warm up to Robert out of self-preservation. Back to the present, Vicente looks like a beautiful woman, like one of the idealized objects in Robert’s paintings. Robert has become an outright monster. As scholar David Bordwell observed, “The flashback structure doesn’t fulfill the film’s opening so much as yank the bottom out from it.”

To be sure, the scene between Zeca and Robert’s patient—where Zeca rapes Vicente in his untested orifice, believing him to be Gal—becomes even more disturbing on a second viewing, knowing Vicente maintains his outward appearance as Vera throughout the assault. Gradually, Almodóvar manages to create a troubling empathy for Vicente. Admittedly, the first time watching The Skin I Live In, one yearns for vengeance against the rapist and may even feel robbed of that catharsis as the film skews any hope of moral certainty. However, in subsequent viewings, the extent of Almodóvar’s interest in moral uncertainties, defying the expectations of a simple revenge story, becomes sadistic if rewarding. Almodóvar doesn’t forgive Vicente, nor does he wholly condemn Robert. Rather, he challenges his viewer’s capacity for empathy by presenting us with two options: a rapist or the mad scientist who kidnaps and mutilates him. The director told The Wall Street Journal, “My challenge in the adaptation of the novel was to make a unique character like Robert believable. I guess that people can be horrified by him too, but I don’t find him grotesque.”

Still, Almodóvar questions Robert’s abuses of power—his obvious privilege and wielding of science for personal ends. Robert is a man driven by his ability to shape life according to his will. Yes, he embodies the mad scientist trope. But Almodóvar hints at his far-reaching preoccupation with control in less obvious ways, such as Robert’s bonsai trees, a plant that must be groomed, shaped with wire, and manicured to reformat Nature according to a new aesthetic design. In this way, Almodóvar does not judge his characters; he seeks to understand them. No matter how badly the viewer wants to project moral poles onto the proceedings, the director doesn’t play into that desire. By the final frames, Almodóvar leaves his audience unable to reconcile the film’s moral position. It’s a choice that causes many critics and moviegoers to recoil. In his review, Roger Ebert remarked, “This film must be credited with expressing exactly what Almodovar wanted to say, but I am not sure I wanted to hear it.”

Still, Almodóvar questions Robert’s abuses of power—his obvious privilege and wielding of science for personal ends. Robert is a man driven by his ability to shape life according to his will. Yes, he embodies the mad scientist trope. But Almodóvar hints at his far-reaching preoccupation with control in less obvious ways, such as Robert’s bonsai trees, a plant that must be groomed, shaped with wire, and manicured to reformat Nature according to a new aesthetic design. In this way, Almodóvar does not judge his characters; he seeks to understand them. No matter how badly the viewer wants to project moral poles onto the proceedings, the director doesn’t play into that desire. By the final frames, Almodóvar leaves his audience unable to reconcile the film’s moral position. It’s a choice that causes many critics and moviegoers to recoil. In his review, Roger Ebert remarked, “This film must be credited with expressing exactly what Almodovar wanted to say, but I am not sure I wanted to hear it.”

Merciless revenge schemes aside, Almodóvar’s scenario challenges how his viewer will think about gender by deconstructing the male gaze, the classical feminine state of being gazed upon, and a myriad of variations in-between that confront how these conventional ideas came to be. The Skin I Live In asks compelling questions: Do the precepts of gender binarism apply to Vicente and Vera? Does Vera exist at all, or is she merely Robert’s horrifying fantasy? Can a female identity be forced upon another? Does gender exist on the surface or underneath? Almodóvar explores these issues without settling on a single perspective about transgender identity, regardless of whether the change occurs by choice or by a madman. Instead, consider that the acts represented in the film amount to Robert’s projection of what it means to be female. Indeed, looking at Robert’s view of women through the Vicente-Vera change supplies further insight into the character and his obsession with surfaces. Consciously or not, Robert shapes Vicente into Vera according to the schema outlined in his views on women, represented in his paintings, which portray figures designed to entice the male gaze.

The symbolism of skin goes even deeper. Skin is the layer through which people experience pleasure and pain, the barrier between selfhood and everything else. Skin both shapes identity and remains independent of it, providing a container and a frontage to the person inside. Depending on the individual, the skin defines the interior; others may experience a vast expanse between the mind and body, prompting a transition. When Robert sets out to make a woman out of Vicente, he creates Vera in name only and, in doing so, reveals his superficial understanding of female identity. The Skin I Live In, then, is about how patriarchal definitions of gender imprison women—how they attempt to outline gender boundaries through social control, expectation, persistent observation, and ultimately discipline, all for a surface understanding of what it means to be female. Author and practicing psychoanalyst Arlene Kramer Richards observes that Almodóvar’s film takes a critical look at foundational myths about “the making of a woman,” in that sources ranging from Adam’s rib to Sigmund Freud have defined women in relation to men. For example, Eve was created in the Garden of Eden to keep Adam company and bring him pleasure, establishing a patriarchal idea about femininity’s subservience. Similarly, Freud argued that women experienced anxiety over the absence of a phallus, an idea that suggests the primary nature of the masculine—that humanity starts with men, and women are defined in terms of masculinity or lack thereof.

Robert subscribes to these narrow and traditional definitions, focusing his attention on surfaces—the skin above all. Robert has not only replaced Vicente’s skin with eerily plastic-looking pigskin and physically attractive features; he has promised his victim that sex will become pleasurable in this new state. This is not a form of transgender reassignment or even a Pygmalion scenario; instead, it begins as an act of revenge to castrate the rapist of his offending organ before taking on notes of Frankenstein. The scientist names his creation and molds him into the concept of a woman, starting with the vagina and moving outward. To survive, Vicente fulfills Robert’s view of a woman by becoming a seductress, using his new body to tempt his captor. Herein is the rich metaphor of Robert as an enforcer of the patriarchal social codes that promote gender binarism and disparity, and Vicente as an (unwilling) adherent to those precepts. More disturbing is how, when Robert takes advantage of his subject sexually, he has sex with the mirror image of his wife, a shadow of his daughter’s rapist, and his equivalent of Frankenstein’s monster. Although Robert crafts a woman out of Vicente the only way he knows how—by creating a pretty surface and forcing his desire onto it—he never turns Vicente into a woman, psychologically. Of course, Vicente’s captivity, along with the many cases of abuse against him, allows him to walk in a woman’s shoes. But the experience equates to an act of forced empathy and recovery for a man who has preyed on women.

Robert subscribes to these narrow and traditional definitions, focusing his attention on surfaces—the skin above all. Robert has not only replaced Vicente’s skin with eerily plastic-looking pigskin and physically attractive features; he has promised his victim that sex will become pleasurable in this new state. This is not a form of transgender reassignment or even a Pygmalion scenario; instead, it begins as an act of revenge to castrate the rapist of his offending organ before taking on notes of Frankenstein. The scientist names his creation and molds him into the concept of a woman, starting with the vagina and moving outward. To survive, Vicente fulfills Robert’s view of a woman by becoming a seductress, using his new body to tempt his captor. Herein is the rich metaphor of Robert as an enforcer of the patriarchal social codes that promote gender binarism and disparity, and Vicente as an (unwilling) adherent to those precepts. More disturbing is how, when Robert takes advantage of his subject sexually, he has sex with the mirror image of his wife, a shadow of his daughter’s rapist, and his equivalent of Frankenstein’s monster. Although Robert crafts a woman out of Vicente the only way he knows how—by creating a pretty surface and forcing his desire onto it—he never turns Vicente into a woman, psychologically. Of course, Vicente’s captivity, along with the many cases of abuse against him, allows him to walk in a woman’s shoes. But the experience equates to an act of forced empathy and recovery for a man who has preyed on women.

The Skin I Live In also retells the Greek myth of Tiresias, who experienced life as a woman after Hera, Queen of the gods, punished him for interrupting a pair of copulating snakes. When Tiresias returned to the same snake mating spot seven years later, Hera reversed her spell and restored Tiresias to manhood. Then, as the story goes, Hera and Zeus, caught in a marital spat, argued about which gender experienced more pleasure during sex. Ever jealous and tempestuous, Hera argued that men enjoy sex more than women. Zeus believed the opposite. Who better than Tiresias, who apparently had sex during his seven years in female form, to settle the matter with his perspective? Tiresias explained that he enjoyed sex more as a woman. Hera, upset over losing the argument, then blinded Tiresias. Feeling awful about the whole situation, Zeus gave the man the abilities of a prophesier as consolation. However, nothing magical happens to Vicente at the end of The Skin I Live In. Robert fails in forcing the transition. Gender goes deeper than the skin, and Vicente has not changed beneath the surface. Seeing his missing person’s picture in the paper reminds him of what Robert has done. He kills Robert and Marilia, then escapes home to his mother’s second-hand women’s clothing shop, living in the body of what Richards calls a “second-hand woman.”

Since its release, The Skin I Live In has prompted think pieces aplenty and heated reactions about what the film conveys about gender and power, and how those elements fit into the horror genre. Critics have compared the film to titles like Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), Brian De Palma’s Dressed to Kill (1980), and the Sleepaway Camp slasher series—all of which use uncertain gender or transgender people as a source of scares. These films and many others like them treat transgender identities like an affront to Nature, depicting them as a form of monstrosity. For instance, the razor-wielding murderer in Dressed to Kill is the feminine half of a male psychiatrist’s split personality. But Almodóvar does not reinforce the link between monstrosity and transgenderism, even if his film exists in the same genre soup. His film’s monster is Robert, who projects female archetypes onto Vicente, but Vicente never fully identifies as female. Although he bears the external components of a female body, the social construction of gender does not apply to him. Inside, he remains “Vicente,” and reintroduces himself under that name when reunited with his mother. If there is a tragedy in the film, it is that Vicente remains a man trapped in an artificial female body.

The true horror of The Skin I Live In, and subsequently the main issue that continues to nag at many critics and moviegoers, is the film’s detachment, coldness, and cruelty. Almodóvar is known and celebrated for his passions, for creating films that entice the viewer and invite them to enjoy the fearless, indulgent ways that he breaks taboos, titillates, and unashamedly gives in to desires. Even something as potentially unsettling as Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! becomes a sheer pleasure to watch in his hands. His other films involving killers, such as Matador and Bad Education (2004), contain an undeniable eroticism, regardless of their subject matter. But his 2011 film ran counter to everything the Spanish enfant terrible had done before, as evidenced by the lukewarm critical response, which was positive, albeit tempered (Richard Corliss called it “middling Pedro” in his Time review). Although it contains many narrative touchpoints found in the director’s work—the trauma of a lost child, the unexpected reveal of family ties, the shifting of sympathies after an edifying flashback—it doesn’t perform these melodramatic feats with the joyful abandon of his usual work. Many expected the delights of his sexy Spanish comedies given that Almodóvar had never made a horror film before, and the result is something unexpected.

The true horror of The Skin I Live In, and subsequently the main issue that continues to nag at many critics and moviegoers, is the film’s detachment, coldness, and cruelty. Almodóvar is known and celebrated for his passions, for creating films that entice the viewer and invite them to enjoy the fearless, indulgent ways that he breaks taboos, titillates, and unashamedly gives in to desires. Even something as potentially unsettling as Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! becomes a sheer pleasure to watch in his hands. His other films involving killers, such as Matador and Bad Education (2004), contain an undeniable eroticism, regardless of their subject matter. But his 2011 film ran counter to everything the Spanish enfant terrible had done before, as evidenced by the lukewarm critical response, which was positive, albeit tempered (Richard Corliss called it “middling Pedro” in his Time review). Although it contains many narrative touchpoints found in the director’s work—the trauma of a lost child, the unexpected reveal of family ties, the shifting of sympathies after an edifying flashback—it doesn’t perform these melodramatic feats with the joyful abandon of his usual work. Many expected the delights of his sexy Spanish comedies given that Almodóvar had never made a horror film before, and the result is something unexpected.

Almodóvar’s approach to The Skin I Live In has been described as having Hitchcockian suspense, De Palma’s sexual violence, and a downright Cronenbergian preoccupation with the mind-body dichotomy and transformation. To watch The Skin I Live In is to feel the separation between the mind and body, to feel trapped within a surface that may prove inadequate, faulty, and altogether not one’s own. The same brand of body horror propels David Cronenberg’s The Fly (1986)—the sense of being trapped inside a dissociated container, along with a disturbing element of bodily repulsion. Even the sexual acts in Almodóvar’s film run counter to the usual pleasures of his work; they consist of rape, discomfort, and violations of varying extremes. But underneath the film’s dermis resides Almodóvar’s persistent interest in and tendency to transgress gender, sexuality, and desire in its many messy forms. His film bursts with details that unnerve the viewer, leaving us shaken and uneasy, uncovering how gender goes beyond the biological. The film contains great formal beauty too, but Almodóvar does not try to gratify his audience with his story; he exposes them to something unspeakable. It is a visually and thematically sublime film, and a true expression of horror in how Almodóvar has subverted his usual desirous cinema into something altogether unsettling.

Bibliography:

Bordwell, David. “Son of seduced by structure.” Observations on Film Art, 5 October 2011. http://www.davidbordwell.net/blog/2011/10/05/son-of-seduced-by-structure/. Accessed 31 January 2022.

Corliss, Richard. “The Skin I Live In: Almodóvar’s Human Centipede.” Time, 13 October 2011. https://entertainment.time.com/2011/10/13/the-skin-i-live-in-almodovars-human-centipede/. Accessed 31 January 2022.

Davidson, Justin. “Dr. Almodóvar.” New York Magazine, 19 August 2011. https://nymag.com/guides/fallpreview/2011/movies/pedro-almodovar-antonio-banderas/. Accessed 31 January 2022.

Ebert, Roger. “The Skin I Live In movie review.” RogerEbert.com, 19 October 2011. https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/the-skin-i-live-in-2011. Accessed 31 January 2022.

Gutiérrez-Albilla, Julián Daniel. Aesthetics, Ethics and Trauma in the Cinema of Pedro Almodóvar. Edinburgh University Press, 2017.

Richards, Arlene Kramer, et al. (editors). Pedro Almodóvar: A Cinema of Desire, Passion and Compulsion. International Psychoanalytic Books, 2018.

Straus, Frederick (editor). Almodóvar on Almodóvar. Revised edition. Faber and Faber, 2006.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review