The Definitives

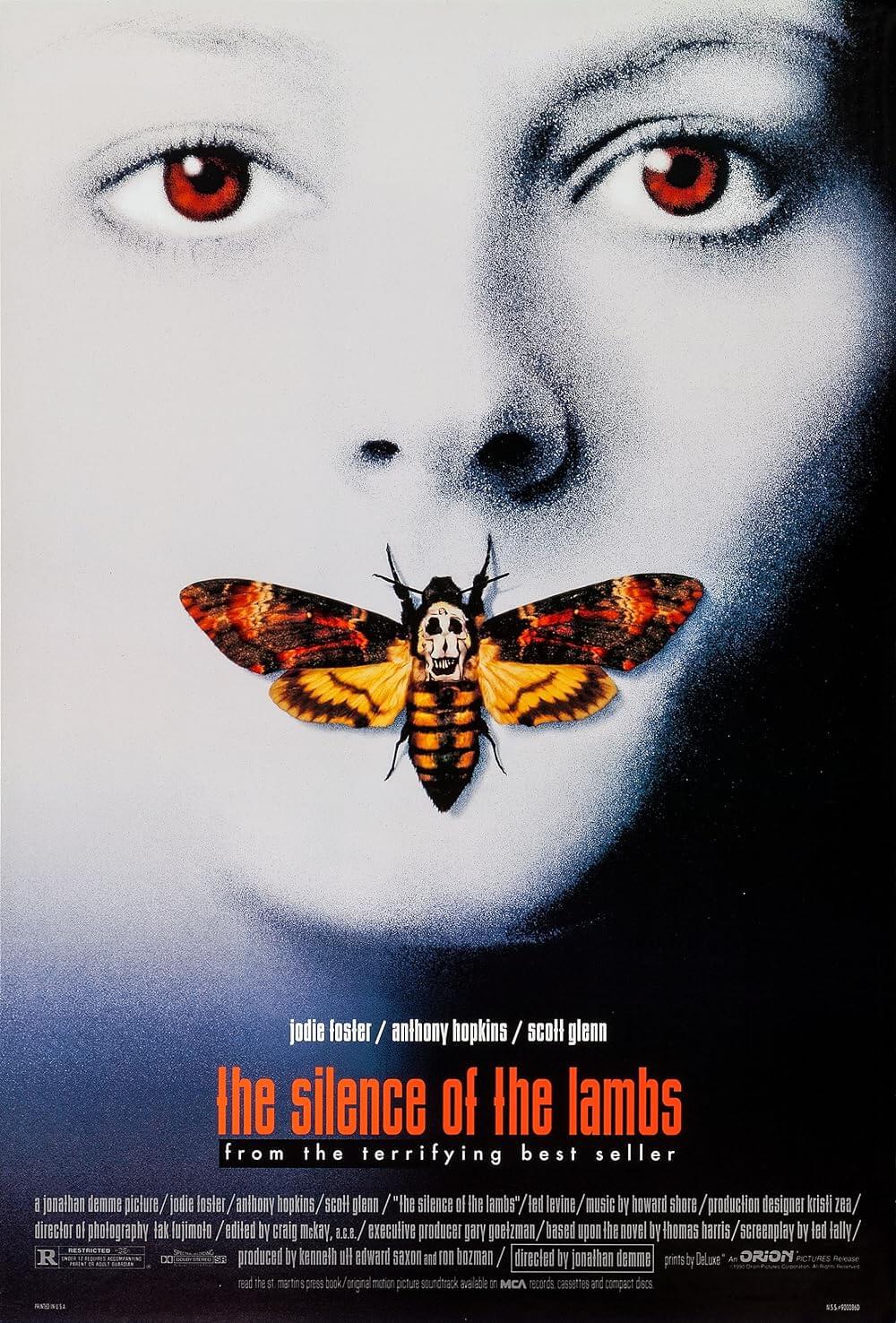

The Silence of the Lambs (1991)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Clarice Starling, a young FBI trainee, navigates an obstacle course at Quantico. Alone in the woods, she pulls herself up a hill by a rope, scales a vertical cargo net, and heads down a foggy trail with no end in sight. A moment later, she’s ordered to the Behavioral Science Division, where she receives an “interesting errand.” She will interview Hannibal “The Cannibal” Lecter, the criminal mastermind, and the only character in The Silence of the Lambs who does not underestimate or overlook Clarice’s potential. The opening’s imagery remains consistent throughout the film. Clarice maneuvers a series of obstacles, some in the form of a repressive organization like the FBI, some in the form of insane criminals. Always, Clarice is alone or discounted in her work by others, but she perseveres at every opportunity. However, the film’s legacy—its memorable story, distinct characters, horrific imagery, and subsequent pop iconography—has been so thoroughly burned into our consciousness that it’s easy to forget what makes the experience endure. This is a rare serial killer film that makes significant variations on traditional themes, offering an account of one woman who saves another woman by defying the limitations of genre norms. Beyond its fringe elements, The Silence of the Lambs is a multifaceted interwork of classical storytelling, horror conventions, and procedural standards, together reshaped into both a feminist landmark and a powerful study of transformation and identity.

Much of the discussion permeating Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs—especially as it relates to the film’s place in pop culture—involves Hannibal Lecter, the character from Thomas Harris’ 1981 novel, Red Dragon, who was played by Brian Cox in Michael Mann’s feature film adaptation, Manhunter (1986), a box-office failure. His blend of sophistication and savagery was irresistible to audiences, making him an anti-hero, or at least a secondary antagonist, compared to the real villains of Harris’ stories—Francis Dolarhyde in Red Dragon and Jame “Buffalo Bill” Gumb (Ted Levine) in The Silence of the Lambs. By the time Harris’ third novel, Hannibal, was published in 1999, Lecter blurred the line between hero and villain. He was the cannibal audiences loved to hate so much that their affection for the character ultimately translated into rooting for him. (The less said about Harris’ ill-conceived prequel, Hannibal Rising, where young Lecter, the ultra-violent protagonist, plots revenge on the German soldiers who ate his sister in World War II, the better.) Even so, Lecter was a secondary character in the first two novels, and the narrative thrust of the story of The Silence of the Lambs resides with Clarice.

Her story in the book and film is classical in nature, following Joseph Campbell’s monomyth archetype wherein the hero embarks on a quest to confront the monster, rescue the damsel, and return wiser for the journey. The serial killer movie usually adheres to this structure, but in the case of most Hollywood genre efforts, the deviations from the classical norms supply the most compelling examples. Anyone can make a boilerplate serial killer yarn about a male cop who catches the bad guy, saves the would-be victim, and achieves some level of personal clarity along the way (see the Alex Cross or Dirty Harry series). Demme’s film reconsiders the classical structure through a series of alterations that continue to differentiate the film, long after Hollywood has returned to standard, competent, but in no way exceptional entries in the serial killer genre. Demme, screenwriter Ted Tally, and star Jodie Foster double-down on the more subtly conveyed themes of feminism from Harris’ novel, making the film a new type of woman’s picture that rethinks the classical narrative structure. Not only does The Silence of the Lambs recast the conventional hero as a woman, it focuses on inner conflicts that emerge in external ways—a series of transformations that occur in every character and appear throughout the film in a variety of visual and thematic motifs.

Her story in the book and film is classical in nature, following Joseph Campbell’s monomyth archetype wherein the hero embarks on a quest to confront the monster, rescue the damsel, and return wiser for the journey. The serial killer movie usually adheres to this structure, but in the case of most Hollywood genre efforts, the deviations from the classical norms supply the most compelling examples. Anyone can make a boilerplate serial killer yarn about a male cop who catches the bad guy, saves the would-be victim, and achieves some level of personal clarity along the way (see the Alex Cross or Dirty Harry series). Demme’s film reconsiders the classical structure through a series of alterations that continue to differentiate the film, long after Hollywood has returned to standard, competent, but in no way exceptional entries in the serial killer genre. Demme, screenwriter Ted Tally, and star Jodie Foster double-down on the more subtly conveyed themes of feminism from Harris’ novel, making the film a new type of woman’s picture that rethinks the classical narrative structure. Not only does The Silence of the Lambs recast the conventional hero as a woman, it focuses on inner conflicts that emerge in external ways—a series of transformations that occur in every character and appear throughout the film in a variety of visual and thematic motifs.

The film’s journey to the screen began when Harris’ second book featuring Lecter debuted in 1988. Gene Hackman and Orion Pictures co-purchased the rights as a project the actor would direct. But after reading Tally’s script, Hackman passed on the project, resolving that the subject matter was too violent for his tastes. At the same time, Jodie Foster had been recommended Harris’ The Silence of the Lambs as a potential source for her next role, and she attempted to acquire the rights but found that Orion had already begun development with Demme heading the production. Demme had just completed work on Married to the Mob (1988) and wanted its star, Michelle Pfeiffer, in the lead role of Clarice Starling. Learning this, Foster insisted on meeting Demme and pitching herself as his second choice. She explained to Demme that she was interested in its story about one strong woman saving another, and that concept struck Demme as a vital theme he would develop in his direction and aesthetic choices. When Pfeiffer eventually backed out of the role due to the visceral subject matter, Foster stepped in. So convinced by her sentiment about Clarice’s endurance and growth as the film’s central theme, Demme named the film’s production company Strong Heart.

The other major strain in The Silence of the Lambs, of course, involves the uniquely American problem of serial killers, a term that had only been established for a couple of decades at that point. The vast majority of the world’s serial killers come from the United States, and most of them are men, many of them from the heartland. At the time of the film’s production, serial killers were also well-worn fodder in the movies. Though rarely labeled as such, they had appeared in everything from Alfred Hitchcock’s The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog (1927) to Fritz Lang’s M (1931), from Charles Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux (1947) to Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1978), and most famously Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). And don’t forget the supernatural B-movie slasher franchises that followed, such as Halloween, Friday the 13th, and A Nightmare on Elm Street. But The Silence of the Lambs employs a more grounded pathology rooted in actual cases. Harris borrowed from a variety of real-life killers, such as Ed Gein and Jerry Brudos, who created so-called art with their victims; Ted Bundy, who sometimes pretended to have a broken arm to gain the confidence of a victim; or Gary Heidnik, who kidnapped women and kept them in a basement pit. He combined elements of each into Buffalo Bill, making the character’s modus operandi oddly familiar, but also different in disturbing and controversial ways.

Moreover, the production of The Silence of the Lambs could make a claim to realism after the FBI approved the script. The bureau also allowed Demme’s crew access to Quantico, believing the picture would encourage recruitment among women, which it did. Foster spent several days in immersive training, while Scott Glenn, who portrays Jack Crawford, the head of the Behavioral Science Division who enlists Clarice Starling to interview Hannibal Lecter, shadowed John Douglas, the FBI’s actual head of that division. Douglas not only consulted on the production but provided the basis of Crawford too (as well as the profilers who appear in series such as Criminal Minds and Mindhunter). Much has been written about the film’s portrait of serial killers, and how actual forensic pathology and criminal profiles inform the story. Amy Taubin’s 1991 cover story in Sight & Sound details how serial killers have emerged as a common thread in Hollywood entertainment and beyond, igniting our fascination with how killers select and hunt their victims, while the FBI hunts serial killers with the same precision. But tracing how The Silence of the Lambs fueled the obsessive interest in serial killers in true crime books, podcast, and other media is not necessarily the goal here, nor is it to chart Hannibal Lecter’s rise in the pop-culture lexicon—even if his iconographic influence cannot be altogether ignored.

Moreover, the production of The Silence of the Lambs could make a claim to realism after the FBI approved the script. The bureau also allowed Demme’s crew access to Quantico, believing the picture would encourage recruitment among women, which it did. Foster spent several days in immersive training, while Scott Glenn, who portrays Jack Crawford, the head of the Behavioral Science Division who enlists Clarice Starling to interview Hannibal Lecter, shadowed John Douglas, the FBI’s actual head of that division. Douglas not only consulted on the production but provided the basis of Crawford too (as well as the profilers who appear in series such as Criminal Minds and Mindhunter). Much has been written about the film’s portrait of serial killers, and how actual forensic pathology and criminal profiles inform the story. Amy Taubin’s 1991 cover story in Sight & Sound details how serial killers have emerged as a common thread in Hollywood entertainment and beyond, igniting our fascination with how killers select and hunt their victims, while the FBI hunts serial killers with the same precision. But tracing how The Silence of the Lambs fueled the obsessive interest in serial killers in true crime books, podcast, and other media is not necessarily the goal here, nor is it to chart Hannibal Lecter’s rise in the pop-culture lexicon—even if his iconographic influence cannot be altogether ignored.

What remains most stirring about The Silence of the Lambs is what initially attracted Foster and Demme to the material. This is the story of a woman undeterred by her station in a world of men, and it’s told with an immersive subjectivity. Clarice Starling succeeds despite the claustrophobic ways in which the characters, situations, and narrative attempt to contain her; she controls her emotions even as she confronts her past traumas; she navigates the advances of various men, deflecting them without sacrificing her professional progress; she even inhabits cramped spaces from the windowless hallways of Quantico to Buffalo Bill’s mazelike basement lair. Clarice is a determined hero, not defined by her sexuality or a love interest; rather, her focus will help her transform into a full-fledged FBI agent and a whole person no longer afflicted by the trauma of her childhood. She is paired with an equally complex killer—Lecter, who is not a raving lunatic or irredeemable monster, but a composed, intelligent, and even considerate person with criminal drives. Clarice’s capacity for empathy extends not only to Lecter and Buffalo Bill but the victims in the Buffalo Bill case, giving her an edge over her male counterparts that leads to her catching the killer.

Clarice is more than a woman cast in the role with masculine characteristics or a role intended for a man (such as Sigourney Weaver’s Ellen Ripley in the Alien series). Clarice’s womanhood is essential to the character’s identity, strength, vulnerability, and unique perspective, all of which give her an advantage. For starters, she’s not a typical FBI candidate. She is not the detached, middle-class, and usually male subject of a specific physical build that the bureau sought during J. Edgar Hoover’s administration. She is a woman; hails from a blue-collar background; and appears shorter than her male counterparts, often by a foot or more. She is emotionally invested in her work yet critical of the bureau’s past. Crawford remarks in their initial scene together, “I remember you from my seminar at UVA. You grilled me pretty hard, as I recall, on the bureau’s civil rights record in the Hoover years.” This reference to the FBI counterintelligence program suggests that Clarice is interested in social justice, and thus she is acutely prepared for the challenges of being a woman in a traditionally male-dominated profession.

Nevertheless, she persists. It’s not a showy performance from Foster. Clarice has only one scene that could be called an emotional outpouring, during her final quid pro quo with Lecter, where she describes the origin of her nightmares—the death of her father, which led to her placement with a relative on a lamb farm, where the sounds of slaughter terrified her and still haunt her. Apart from this moment, the film occupies her position as a woman gazed upon by nearly every man she encounters, from “Multiple” Miggs to an entomologist. She experiences pressure from all sides but maneuvers the obstacles with grace. When Dr. Frederick Chilton (Anthony Heald) from the Baltimore State Hospital for the Criminally Insane makes a pass at her, she turns him down. Later, she uses his apparent attraction to quell his animosity over feeling used as a “turnkey” to access Lecter: “But then I wouldn’t have had the pleasure of your company,” she says. After Crawford suggests to West Virginia law officials that sex crimes shouldn’t be discussed in front of a woman, she still manages to clear the autopsy room of gathering officers, and later still calls Crawford on his inelegant move: “It matters, Mr. Crawford. Cops look at you to see how to act.” Whether it’s a Quantico training scene that finds her taking blows from all sides or literal semen tossed into her face by Miggs, Clarice stands her ground and compartmentalizes her emotions in order to persevere.

Nevertheless, she persists. It’s not a showy performance from Foster. Clarice has only one scene that could be called an emotional outpouring, during her final quid pro quo with Lecter, where she describes the origin of her nightmares—the death of her father, which led to her placement with a relative on a lamb farm, where the sounds of slaughter terrified her and still haunt her. Apart from this moment, the film occupies her position as a woman gazed upon by nearly every man she encounters, from “Multiple” Miggs to an entomologist. She experiences pressure from all sides but maneuvers the obstacles with grace. When Dr. Frederick Chilton (Anthony Heald) from the Baltimore State Hospital for the Criminally Insane makes a pass at her, she turns him down. Later, she uses his apparent attraction to quell his animosity over feeling used as a “turnkey” to access Lecter: “But then I wouldn’t have had the pleasure of your company,” she says. After Crawford suggests to West Virginia law officials that sex crimes shouldn’t be discussed in front of a woman, she still manages to clear the autopsy room of gathering officers, and later still calls Crawford on his inelegant move: “It matters, Mr. Crawford. Cops look at you to see how to act.” Whether it’s a Quantico training scene that finds her taking blows from all sides or literal semen tossed into her face by Miggs, Clarice stands her ground and compartmentalizes her emotions in order to persevere.

In her monograph for the British Film Institute, Yvonne Tasker observes how The Silence of the Lambs is modeled like a classical Hollywood women’s picture, similar to films like Woman of the Year (1942) and Mildred Pierce (1945), which explore the protagonist’s relationship with social expectation and professional ambition. At the root of such stories is a desire to find one’s identity—to emerge from, and in some cases conform to, established gender roles. With the idea of emphasizing Clarice’s strength in mind, Demme and editor Craig McKay downplayed Crawford in the original cut, including any romantic hints between the character and Clarice. With less of Glenn’s presence, Foster occupies a number of scenes in solitude. Clarice often appears alone, such as her breakdown in the parking lot after her initial encounter with Lecter, her despondent walk in the airport, and her visit to the storage facility where she finds the head of Bill’s first victim, Benjamin Raspail. Clarice’s management of people also demands attention. With Lecter, she is courteous and honest, earning his respect for the way she gives him a taste of humanity again. Note also how she blinks when she lies about “the pleasure of your company” to Chilton or her ham-fisted segue for Lecter to “lend us your view” on a questionnaire, as though she has too much integrity to lie well.

These moments underscore her attempts—sometimes notably clumsy attempts—to prevail in a man’s world. Indeed, she is not always successful. When Lecter eviscerates her with a quick assessment of her class and background in their first encounter (“You’re not more than one generation from poor white trash, are you, Agent Starling?”), she fires back: “Are you strong enough to point that high-powered perception at yourself? […] Maybe you’re afraid to.” Her attempt to turn the conversation around in her favor results in Lecter’s aggressive response with an oft-imitated line: “A census taker once tried to test me. I ate his liver with some fava beans and a nice Chianti.” Hopkins ad-libbed the slithering sound that follows as a joke on the jovial set, and Demme left it in. It’s at once an iconic moment in pop-culture history and the single flourish that feels out of character for Hannibal Lecter. In any case, Clarice’s vulnerability in moments such as this becomes her strength. Her empathy for Bill’s victims—one of whom she helps autopsy in West Virginia, not far from where she grew up—enables her to find Jame Gumb, a reversal of how Will Graham, the protagonist in Red Dragon, prevailed by placing himself in the mind of the killer.

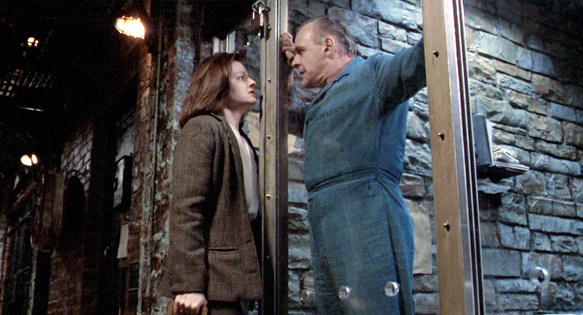

Demme works to isolate and focus on Clarice more than Harris’ novel did, submerging the viewer in her subjectivity through image and sound. He accomplishes this through a combination of increasingly tight close-ups and characters who look directly into the camera positioned from Clarice’s viewpoint. The direct camera technique places the viewer into Clarice’s perspective so she, thus the camera, peers directly into the eyes of Lecter, Crawford, fellow trainee Ardelia (Kasi Lemmons), and others—and these characters seem to look deep into Clarice. By contrast, Clarice rarely meets their gaze. When the shot is flipped to Lecter or Crawford’s perspective looking at Clarice, she often looks just to the side of the camera, not quite engaging it, as if she’s using a technique to look at someone’s forehead or nose to avoid the anxiety of direct eye contact. Only with Lecter do Clarice’s eyes seem fully, and unavoidably, arrested by his gaze. Demme uses this device in other films, but never to this extent, and never has it aligned so well with a film’s theme. And in a similarly immersive plunge into Clarice’s subjectivity, Howard Shore’s score does not play into the typical pangs that accompany the jump-scares in many horror film scores. The music is operatic, following Clarice’s emotional journey of discovery rather than telling the audience how scared to feel in a particular moment. In the music, the audience feels Clarice’s complicated past and yearning to move beyond it, into a career at the FBI. Much like the direct camera technique, the score is an extension of Clarice’s point of view.

Demme works to isolate and focus on Clarice more than Harris’ novel did, submerging the viewer in her subjectivity through image and sound. He accomplishes this through a combination of increasingly tight close-ups and characters who look directly into the camera positioned from Clarice’s viewpoint. The direct camera technique places the viewer into Clarice’s perspective so she, thus the camera, peers directly into the eyes of Lecter, Crawford, fellow trainee Ardelia (Kasi Lemmons), and others—and these characters seem to look deep into Clarice. By contrast, Clarice rarely meets their gaze. When the shot is flipped to Lecter or Crawford’s perspective looking at Clarice, she often looks just to the side of the camera, not quite engaging it, as if she’s using a technique to look at someone’s forehead or nose to avoid the anxiety of direct eye contact. Only with Lecter do Clarice’s eyes seem fully, and unavoidably, arrested by his gaze. Demme uses this device in other films, but never to this extent, and never has it aligned so well with a film’s theme. And in a similarly immersive plunge into Clarice’s subjectivity, Howard Shore’s score does not play into the typical pangs that accompany the jump-scares in many horror film scores. The music is operatic, following Clarice’s emotional journey of discovery rather than telling the audience how scared to feel in a particular moment. In the music, the audience feels Clarice’s complicated past and yearning to move beyond it, into a career at the FBI. Much like the direct camera technique, the score is an extension of Clarice’s point of view.

The unobtrusive form, which disappears into Clarice’s vantage point, is an oddity in Demme’s career by 1991. Like many filmmakers of his generation, Demme had started under Roger Corman, making B-movie fare like Caged Heat (1974) and Crazy Mama (1975) in the fertile training ground of American International Pictures. He soon moved on to stories about outsiders, like Melvin and Howard (1980), and varied his output in documentaries, quirky comedies, and themes of activism and social justice. After seeing his talent for crafting renegade hipness in Stop Making Sense (1984) and Something Wild (1986), his stylistic restraint in The Silence of the Lambs is somewhat surprising. He doesn’t conform to the dark psychological thriller aesthetic usually employed by Hollywood. Most of the film might even be called bright and plainly shot. Demme told Tak Fujimoto that he wanted the audience “to see everything”—a stark contrast to serial killer films shrouded by shadows in the years to come. The autopsy scene, for instance, does not unfold in a morgue with a single point of light illuminating the scene, as many so-called atmospheric procedurals do. The scene is bright, and the tangible body—a live actor playing a corpse rather than a special prop—looks like something dragged out of a river. The reactions of Crawford and the others at the smell only accentuate the scene’s veracity.

Even though most of The Silence of the Lambs appears relatively unembellished, this straightforwardness is offset in a few key scenes in which Demme amplifies the sense of dread and isolation to disorienting extremes. Clarice’s exchanges with Lecter and the climactic confrontation with Buffalo Bill shift the proceedings from a procedural to a horror film, complete with nightmarish set design, lighting, and imagery. When we follow Clarice down into the bowels of a Baltimore State Hospital to meet Lecter, she descends level after level, until the subterranean sub-basement glows with a hellish red light, as though she has entered the underworld, a place humming with loud industrial sounds and echoing like a dungeon. Production designer Kristi Zea based the block on the cells used to hold Nazi criminals during the Nuremberg trials, and the barred cells appear almost medieval. Lecter’s shatterproof glass cell, however, looks as though Chilton wanted to preserve his prized specimen, a telling choice informed by the need to capture Hopkins on camera without bars dominating the frame. These expressive touches reach their peak in Buffalo Bill’s labyrinthine lair, where Zea created an impossible Gothic space that unfolds with sinister confusion beneath an otherwise traditional home. It’s as though Buffalo Bill has carved out a series of rooms and spaces outward from the house, like an ant expanding its colony beyond the mound overhead.

Of course, the film’s use of violence and suspense, too, takes the otherwise grounded temperament of The Silence of the Lambs into the realm of horror. Zea was inspired by artists from Blake to Bacon to Bosch—all iconoclasts who created their own mythological imagery—to create scenes of gore and bloodshed. The symbolic quality of the violence, such as how Lecter displays the gutted police officer in the courthouse or Bill’s transformative agenda, elevates the violence into something awesome and terrible. But the violence is never for the sake of a shock alone; a psychological undercurrent prevails in each sequence, accompanied by a rich symbology. For example, the climax is not only about stopping Buffalo Bill; it is also about rescuing his latest victim, Catherine Martin (Brooke Smith), who represents a “lamb” that Clarice must save to stop her nightmares, as indicated in her psychoanalytic discussions with Lecter. But just as Clarice is not Hollywood’s standard FBI agent, Catherine is not a typical damsel in distress. She finds a way of luring Bill’s dog into the pit where she has been left (“Down here you sack of shit!”), and uses the injured animal to negotiate with her captor. Before he can decide how to respond, his doorbell rings.

Of course, the film’s use of violence and suspense, too, takes the otherwise grounded temperament of The Silence of the Lambs into the realm of horror. Zea was inspired by artists from Blake to Bacon to Bosch—all iconoclasts who created their own mythological imagery—to create scenes of gore and bloodshed. The symbolic quality of the violence, such as how Lecter displays the gutted police officer in the courthouse or Bill’s transformative agenda, elevates the violence into something awesome and terrible. But the violence is never for the sake of a shock alone; a psychological undercurrent prevails in each sequence, accompanied by a rich symbology. For example, the climax is not only about stopping Buffalo Bill; it is also about rescuing his latest victim, Catherine Martin (Brooke Smith), who represents a “lamb” that Clarice must save to stop her nightmares, as indicated in her psychoanalytic discussions with Lecter. But just as Clarice is not Hollywood’s standard FBI agent, Catherine is not a typical damsel in distress. She finds a way of luring Bill’s dog into the pit where she has been left (“Down here you sack of shit!”), and uses the injured animal to negotiate with her captor. Before he can decide how to respond, his doorbell rings.

The final confrontation is about Clarice overcoming the male gaze that has afflicted her throughout the film. Demme masterfully anticipates the final sequence using textbook Hitchcockian suspense when she comes face-to-face with Jame Gumb—preceded by a sharp sequence of parallel editing between Clarice ringing Buffalo Bill’s doorbell and the FBI raiding the wrong house. The audience knows his true identity is Buffalo Bill, but she does not. When she finally realizes this and chases him into his basement lair, the scene shifts into the subjectivity of the killer. His night-vision goggles serve as a phallic extension of his gaze, only slightly less apparent than the camera-mounted knife in Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960). We’re forced to watch from this uneasy perspective, heightening our terror out of fear for Clarice. When she shoots Bill down after hearing the click of his pistol’s hammer, her bullets crack the blacked-out window well, illuminating the darkened room. It’s a sequence of symbolic violence that exhilarates the viewer, but it represents Clarice’s growth beyond the darkness of her past. Such symbolism is classical and readable, but it also deepens the character of Clarice and rewards repeated viewings.

The Silence of the Lambs is a wellspring of classical storytelling and symbolism, laden with apparent motifs that engage the viewer in a sly form of amateur detection. Every scene contains a line of dialogue, a visual hint, or a play on words that is rewarded with a detail later in the film. The Death’s-Head Moth remains an early indication, with the symbolism of a cocoon found in both a victim’s mouth and another’s decapitated head. When the moth appears in Jame Gumb’s house, it signals to Clarice that she has the right man. But it’s less obvious that Lecter may have been pointing to Jame Gumb all along. Consider the drawings in Lecter’s cell, one of which captures the view from the Belvedere in Florence—with “bel” meaning beautiful and “vedere” meaning view, signaling the view that Lecter so desires. Is it a cruel coincidence that Buffalo Bill’s home is located in Belvedere, Ohio, the place where he first began to covet that which he saw every day, his first victim? Or did Lecter draw this image in anticipation of the FBI’s inevitable intent to question him about Buffalo Bill to conceal a hint in plain sight—similar to his word games with Clarice to “look deep inside yourself” (a wink to the Yourself Storage, where Benjamin Raspail’s head was stored), Miss Hester Mofet (“miss the rest of me”), or the anagram Louis Friend (an anagram for iron sulfide or fool’s gold). These sorts of games, typical of Lecter, also underscore the pleasure of poring over the film.

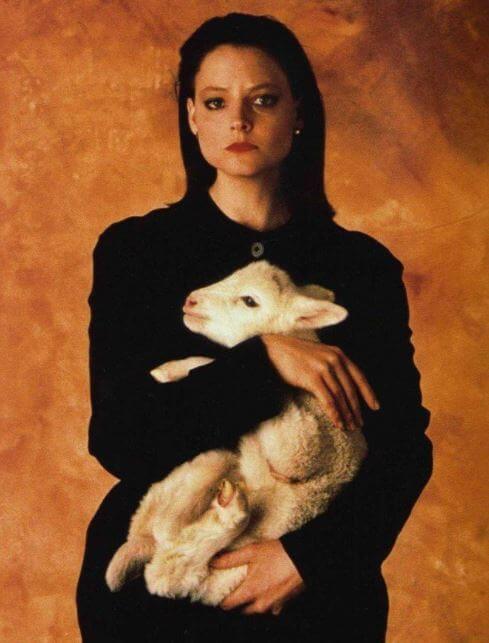

Fortunately, the gamesmanship of The Silence of the Lambs is not merely an empty puzzle for the audience to decipher; Clarice’s encounters with Lecter bear psychological significance and a layering of character. In their few encounters, which amount to just a few minutes of screen time, Lecter uses his games to assess Clarice, quizzing her to test her knowledge and mettle. He recognizes how a damaged childhood can produce someone like Buffalo Bill, but it can also produce someone like Clarice Starling. How the individual handles their trauma defines them in this film. Lecter, above all, recognizes this about her and, bored with killers like Jame Gumb who fail to become something, he compliments her. “I think it would be quite something to know you in private life,” he says, admiring her ability to produce something positive from her tragic past—something that in his experience with psychopaths and killers must be rare indeed. His admiration for Clarice makes us admire her even more. And like the overall film itself, Lecter relies on classical imagery, as he makes associations between Clarice and the lamb (a traditional symbol of innocence) she failed to rescue as a child. His association between Clarice and the lamb is so absolute, he must capture the idea in a sketch, made in the manner of a Renaissance portrait. He also orders a meal of “lamb chops, extra rare,” perhaps to figuratively consume Clarice rather than feel compelled to actually do so.

Fortunately, the gamesmanship of The Silence of the Lambs is not merely an empty puzzle for the audience to decipher; Clarice’s encounters with Lecter bear psychological significance and a layering of character. In their few encounters, which amount to just a few minutes of screen time, Lecter uses his games to assess Clarice, quizzing her to test her knowledge and mettle. He recognizes how a damaged childhood can produce someone like Buffalo Bill, but it can also produce someone like Clarice Starling. How the individual handles their trauma defines them in this film. Lecter, above all, recognizes this about her and, bored with killers like Jame Gumb who fail to become something, he compliments her. “I think it would be quite something to know you in private life,” he says, admiring her ability to produce something positive from her tragic past—something that in his experience with psychopaths and killers must be rare indeed. His admiration for Clarice makes us admire her even more. And like the overall film itself, Lecter relies on classical imagery, as he makes associations between Clarice and the lamb (a traditional symbol of innocence) she failed to rescue as a child. His association between Clarice and the lamb is so absolute, he must capture the idea in a sketch, made in the manner of a Renaissance portrait. He also orders a meal of “lamb chops, extra rare,” perhaps to figuratively consume Clarice rather than feel compelled to actually do so.

Although audiences remain fascinated by Lecter, the mad genius whose literary roots reside in the duality of Jekyll and Hyde or Dr. Frankenstein and his monster, Clarice, though less flashy, remains the more complex character because of her transformation. Transformation is a predominant theme in The Silence of the Lambs, emerging in the metamorphosis of the Death’s-Head Moth, and how that reflects Bill’s attempt to transform into, and thus possess, a woman. It also appears in Bill’s development from the fledgling killer of Benjamin Raspail to a full-fledged serial killer; in Clarice’s progress as an agent-in-training to a badged officer in the final graduation scenes; in Clarice working through her traumatic memories from her childhood and overcoming them during the case. Lecter does not grow, and though it’s tempting to suggest he emerges from the cocoon of his cell in the final scene, his freedom does not mirror the change that occurs in Clarice. This should not suggest that the father-daughter (or in Hannibal, husband-wife) relationship between Clarice and Hannibal remains uninteresting, just not paralleled in the same ways as Clarice and Buffalo Bill. Rather, the pairing of Clarice and Lecter, like so many aspects of The Silence of the Lambs, is a classical one—an oppositional relationship that echoes Sherlock Holmes and Moriarty, the investigator and respectable criminal mastermind. Lecter may escape to the Bahamas, where he pursues Chilton to “have a friend for dinner,” but it is Clarice’s growth that rewards the viewer most.

Both at the time of its release and today, the nature of Jame Gumb’s transformation has resulted in criticisms of The Silence of the Lambs. Some viewers interpreted the character’s nipple ring, Bichon Frise named Precious, and naked dance with his genitals tucked between his legs as somehow coded gay, suggesting the film links queerness and violence. Critics and members of the LGBTQ+ community protested the film in 1991, citing this as another in a long line of queer or transgender killers in Hollywood movies, including Cruising (1980), Dressed to Kill (1980), Sleepaway Camp (1983), and JFK (1991). But Levine argues that he played Buffalo Bill as a heterosexual male who wants to possess a woman so completely that he endeavors to literally climb into her skin, which is why his character skins women to make a woman suit. The film clearly states that he is not a “transsexual,” the term used at the time, and Clarice is quick to note there’s “no correlation between transsexuals and violence.” Rather, he is labeled a psychopath who coopts transsexualism as an answer to his own disturbed and muddled impulses toward transformation—just as he adopts other symbols, such as his Venus of Urbino necklace, pink swastika sheets, and the Death’s-Head Moth to fit his own needs. His reasons appear to be his own, and the film makes no overarching statement about society’s labels or prejudices about sexuality. And while the protests oversimplified Buffalo Bill as another example of the gay killer stereotype, the queer community’s concern that someone else would misread the film, and draw a connection between gay men and violence, were understandable. When placed into the greater context of gay and transgender killers, it becomes a disturbing pattern about which the protests help raise awareness.

But then, everyone had a strong reaction to The Silence of the Lambs when it opened on Valentine’s Day in 1991. It’s not the sort of film you could watch and, love it or hate, not have a strong opinion about. The film lasted five weeks in the number-one spot at the box office, and it lingered in the top ten much longer than that. It was an unexpected sensation, earning $131 million domestically on a budget of under $20 million. And apart from the discussion about queer representation, and a few critics who remarked on how the film made Lecter too charismatic for his own good (or the audience’s), most celebrated its elevation of the horror genre from cheap, gory thrills to psychologically complex storytelling. Carol Clover called such movies “close to being slasher films for yuppies,” and Yvonne Tasker hinted that it was “exploitation cinema for the middle-class.” Horror was suddenly expanding beyond the usual audiences of delighted teenagers; it was no longer B-movie fare but mainstream filmmaking that appealed to the masses. Anthony Hopkins’ glaring eyes donned several magazine covers from the period, and the relatively little-known actor from The Lion in Winter (1968) and The Elephant Man (1980) suddenly became a household name. Jodie Foster, fresh from her Oscar for The Accused (1988), posed with lambs in the press, recreating Lecter’s drawing of Clarice. Despite such promotional shenanigans, or perhaps because of them, the film was not forgotten at the 1992 Oscar ceremony. The Silence of the Lambs became one of the only films to win in all of the five major categories, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor, Best Actress, and Best Adapted Screenplay.

But then, everyone had a strong reaction to The Silence of the Lambs when it opened on Valentine’s Day in 1991. It’s not the sort of film you could watch and, love it or hate, not have a strong opinion about. The film lasted five weeks in the number-one spot at the box office, and it lingered in the top ten much longer than that. It was an unexpected sensation, earning $131 million domestically on a budget of under $20 million. And apart from the discussion about queer representation, and a few critics who remarked on how the film made Lecter too charismatic for his own good (or the audience’s), most celebrated its elevation of the horror genre from cheap, gory thrills to psychologically complex storytelling. Carol Clover called such movies “close to being slasher films for yuppies,” and Yvonne Tasker hinted that it was “exploitation cinema for the middle-class.” Horror was suddenly expanding beyond the usual audiences of delighted teenagers; it was no longer B-movie fare but mainstream filmmaking that appealed to the masses. Anthony Hopkins’ glaring eyes donned several magazine covers from the period, and the relatively little-known actor from The Lion in Winter (1968) and The Elephant Man (1980) suddenly became a household name. Jodie Foster, fresh from her Oscar for The Accused (1988), posed with lambs in the press, recreating Lecter’s drawing of Clarice. Despite such promotional shenanigans, or perhaps because of them, the film was not forgotten at the 1992 Oscar ceremony. The Silence of the Lambs became one of the only films to win in all of the five major categories, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor, Best Actress, and Best Adapted Screenplay.

The legacy of The Silence of the Lambs has led to a lasting influence on both psychological thriller and horror films, along with a never-ending franchise. The film is an unmistakable reference point for a long procession of twisted serial killer cinema in the 1990s, with too many of them focused on the increasingly nasty obsessions of their resident killers and too few with female leads. Even in recent decades, serial killer films ranging from David Fincher’s Zodiac (2007) to Kim Jee-woon’s I Saw the Devil (2010) center on male detectives. There are exceptions, ranging from the woman-centric Copycat (1995), which follows Holly Hunter and Sigourney Weaver on the trail of a serial-killer-obsessed-with-serial-killers, to The Cell (1999), about a woman who nearly loses herself in the mind of the killer. The Silence of the Lambs also casts a heavy shadow over Mann’s film and the three subsequent Lecter features, one sequel and two prequels, rendering most of them inessential. The television series Hannibal fares better, deepening Lecter’s character with an inspired reimagining by Mads Mikkelson. Unfortunately, most of the films and TV shows about Harris’ characters have moved away from Clarice and focused on Hannibal Lecter—an “infuriating” digression noted by Taubin. Only thirty years later, in 2021, did Clarice Starling once again take center stage in a CBS series devoted to her character.

It seems almost criminal to write about The Silence of the Lambs and not mention the iconic image of Lecter’s mask, Buffalo Bill’s haunting dialogue (“It rubs the lotion on the skin or else it gets the hose again”), Lecter’s thrilling escape from captivity, or Fujimoto’s diverse array of close-ups that keep Clarice and Lecter’s quid pro quo visually immersive. But the goal here is to acknowledge the film’s greatness by returning our attention to Clarice Starling as the film’s center. Taubin summed it up nicely: “It’s a slasher film in which the woman is hero rather than victim, the pursuer rather than the pursued.” Once you watch the film and look beyond the shocking quality of Buffalo Bill and Lecter’s crimes, we’re left with a richly conceived picture told from Clarice’s perspective, subtly performed by Foster, and thoughtfully supported by Demme’s direction. Rarely has a film gone to such lengths to immerse the viewer in a woman’s subjectivity, capturing how it feels to be gazed upon, while at the same time, using that point of view to better understand the character’s search for self. Beyond its serial killer setup, Clarice’s journey for identity, which draws from classical structures and supplies an inspired variation on them, is what makes The Silence of the Lambs so rewarding time after time.

(Editor’s Note: This review was commissioned on Patreon. Thanks for your continued support, Dustin!)

Bibliography:

Bliss, Michael, and Christina Banks. What Goes Around Comes Around: The Films of Jonathan Demme. Southern Illinois University Press, 1996.

Kapsis, Robert E. (Editor). Jonathan Demme: Interviews. Conversations with Filmmakers Series. University Press of Mississippi, 2008.

Moore, Tracy. “‘Jonathan, Are You Crazy?’: The Making and Meaning of The Silence of the Lambs.” Vanity Fair. 16 February 2021. https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2021/02/the-abiding-complicated-legacy-of-the-silence-of-the-lambs. Accessed 17 February 2021.

Tasker, Yvonne. The Silence of the Lambs. British Film Institute Modern Classics, BFI Publishing, 2002.

Taubin, Amy. “Killing Men,” Sight and Sound, vol. 1, no. 1. May 1991. https://www.bfi.org.uk/sight-and-sound/features/clarice-starling-rise-movie-serial-killer-twin-peaks-silence-lambs-henry-portrait. Accessed 1 February 2021.

—. “The Silence of the Lambs: A Hero of Our Time.” Criterion.com, 19 Feb 2018. https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/5402-the-silence-of-the-lambs-a-hero-of-our-time. Accessed 1 Feb 2021.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review