The Definitives

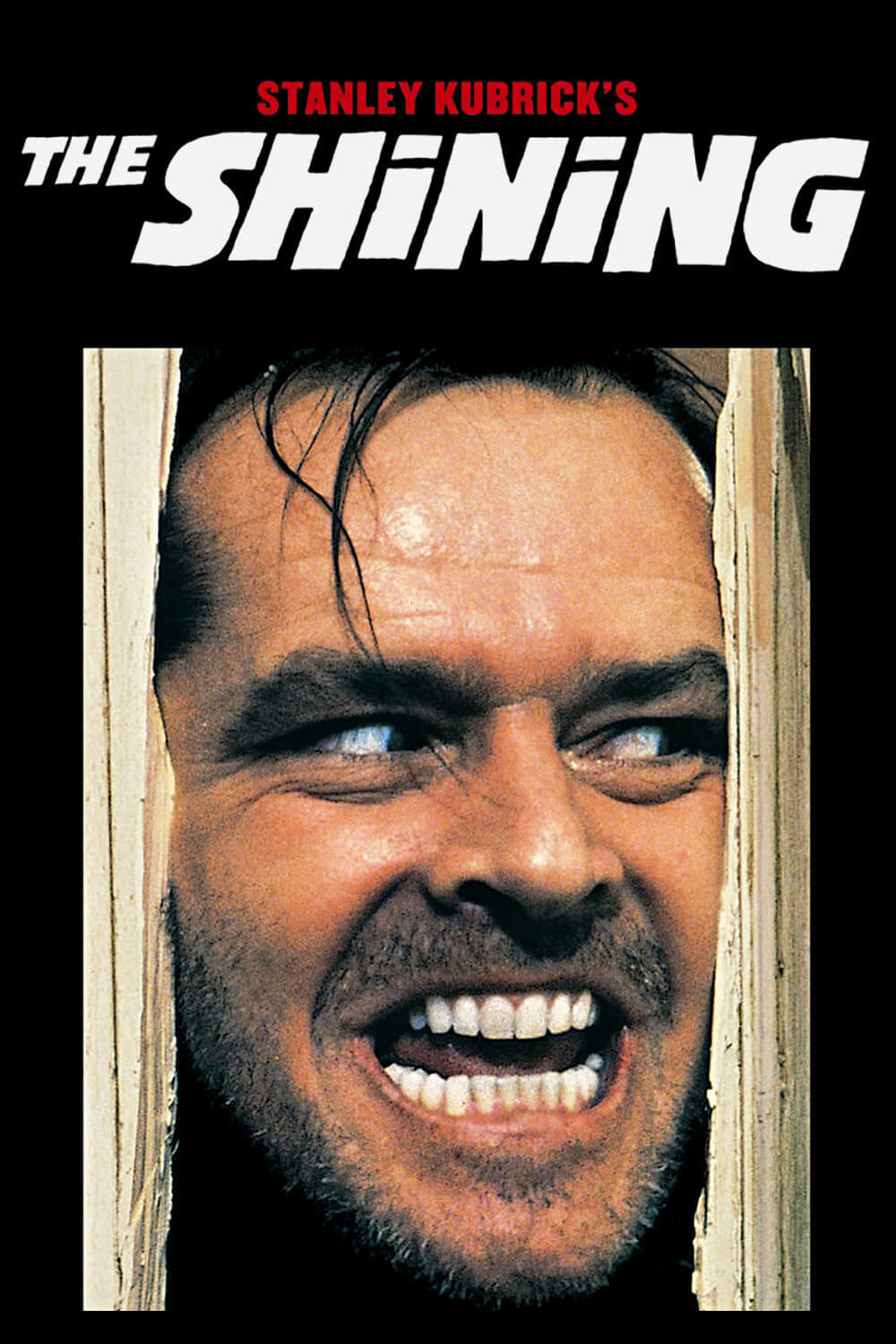

The Shining (1980)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

A metaphysical and narrative maze, The Shining has been watched like so many films by Stanley Kubrick, through waves of deliberation and reconsideration. Although initially reproached for its lack of conventional haunted house scares, the 1980 film has beckoned audiences, critics, and scholars back to the eerie void of the Overlook Hotel, as if anyone who sees the film is fated to repeat an ongoing cycle of examination and speculation. What is it that draws viewers back to the film? What secrets does it hold? What was Kubrick’s grand design for the boundless array of imagery and symbols embedded into every minor detail of the production? Kubrick refused to answer questions about his intended meaning, and in doing so, he preserved the great arcana about his work. But like so many films by the enigmatic director, The Shining is a conceptual arena that Kubrick discovered in the process of making it, thus negating many of the specific, subsequent analyses or eureka moments that claim to have figured out what Kubrick had in mind all along. More even than 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), a film famous for inspiring thought and questions about its intentions, The Shining lends itself to the subjective perceptions and interpretations of the viewer. Standing back and considering the macro concept instead of the micro details planted throughout, one will recognize that Kubrick’s ambition was to create the obsessive attention, maddening circularity, and fixations so commonly stimulated by the film. Rather than search for a decisive reading or interpretation of the specifics, consider instead why The Shining remains an open text, a cinematic maze to be explored again and again.

The Shining is a Gothic tale of domestic violence, yet Kubrick’s puzzlework inhabits the spaces between the lines of the film’s genre. Far removed from its source in Stephen King’s best-selling novel from 1977, the film opens not unlike the grand overture of 2001: A Space Odyssey, ushering the viewer into the Rocky Mountain setting with panoramic shots captured from a low-flying helicopter. These are gliding, majestic images that feel ominous beneath the doomed tones of Wendy Carlos’ synth version of “Dies Irae,” the hymn performed at requiem masses in medieval times to evoke the Day of Judgment. The music suggests the Torrances, Jack and Wendy (Jack Nicholson and Shelley Duvall), along with their young boy Danny (Danny Lloyd), will be judged by forces of ghostly, mythical, and historical import. Once settled into their new quarters at the Overlook Hotel, Jack, who took the job as a winter caretaker so he could outline his latest writing project, goes mad from something: cabin fever, ghostly possession, alcoholism, or perhaps all of the above. The hotel’s apparitions speak to him, compelling him to chop his family into pieces with an ax. But Danny, psychically warned of his father’s impending murder, escapes the hotel with his mother, leaving Jack behind to die, frozen in the hotel’s hedge maze. What remains is an enigma—a compendium of inadequate plotting, stirring imagery, and visual symbols that seem to conflict with Kubrick’s status as a master filmmaker who took years to refine and perfect his projects.

To adapt King’s novel, Kubrick hired Diane Johnson, an author who taught Gothic literature at Berkeley at the time. Tossing aside the elaborate backstories and themes from King’s book, Kubrick and Johnson use the skeletal frame of the original story to fulfill the director’s own conceptual curiosities. The result has all the telltale signs of a traditional Gothic yarn: a large haunted structure, family secrets, psychic abilities, and a ghostly presence. There’s no mention of the circumstances or backstory that brought Jack Torrance to Colorado, where he interviews to become the winter caretaker of the historic Overlook Hotel, nor is there mention of the long, notorious history of the Overlook. In the initial interview, the dry hotel manager, Ullman (Barry Nelson), makes a brief reference to the hotel’s construction on the site of an “Indian burial ground” and droningly shares a story about the former caretaker, named Charles Grady, who murdered his entire family over the isolated winter months. When Grady (Philip Stone) appears to Jack later in the film as an apparition of a British waiter, he goes by the name Delbert Grady, leading to speculation among viewers as to whether this is a continuity error or an intentional clue. As we will see, a lot of The Shining is like that. In any case, King’s novel embraces the traditions of Gothic writers, whereas Kubrick turns the Gothic on its head with an old dark house in which the scariest thing is your husband or father. It’s a subversive film in this way, as Kubrick diverts from the look of a conventional Gothic film such as Vampyr (1932) or The Innocents (1961), both rich in their use of shadow to strike the appropriate mood. Instead, Kubrick shoots almost entirely in well-lit spaces, prompting critic Pauline Kael to ask, “Who wants to see evil in daylight, through a wide-angle lens?”

What might be a spooky tale of a family entering the Gothic realm of a haunted house and maligned spirits gives way to a frightening domestic situation. Kubrick more readily sees the problem of Jack’s alcoholism, misogyny, and abuse as an infection of the Torrance family unit. Alternatively, King had struggled with substance abuse at the time of writing his novel and undoubtedly empathized with the corrupted paterfamilias at the story’s center. From the very beginning, Kubrick sees Jack as the destructive force he is. Watch as Jack dismisses Ullman’s disclosure about Grady, quieting any concern by referring to Wendy as a “confirmed ghost story and horror film nut,” despite no evidence later in the film that Jack ever told his family about the Overlook’s horrible past. Rather, in his interview with Ullman, Jack looks like a man desperate for a job with his accommodating grin and cheery demeanor, a sharp contrast to the often sarcastic and degrading tone he uses with Wendy and Danny. Jack is an abusive patriarch, evident from the belittling way he speaks to his wife, including his nickname for her as “the old sperm bank.” Wendy, chronically codependent, enables the behavior. When a doctor (Anne Jackson) examines Danny after a small seizure—a paranormal warning sign—down the mountain in Sidewinder, Wendy talks about Jack’s abusive behavior like a battered wife, reciting justifications and Jack’s empty promises to quell the doctor’s evident concern. Indeed, the pervasive threat in the film does not originate from an outside source, such as a specter, as many Gothic tales do, including King’s book. At the outset, the danger in the film stems from within the family. Cinematically, it’s a concept that rethinks the traditional narrative drives of horror that bring the family closer together by experiencing a shared trauma, such as The Exorcist (1973) before or Poltergeist (1982) after. In another way, The Shining follows a trajectory in horror films after Rosemary’s Baby (1968) in which a member of the family turns against their own.

Adding further context to The Shining’s place in the horror genre, it was released after a series of films and books had tapped the idea of children with mental powers: the psychic children in Robert Mulligan’s The Other (1972) or Disney’s Escape To Witch Mountain (1975), the angry telekinetics in Brian De Palma’s Carrie (1976) and The Fury (1978), and the “psychoplasmic” offspring in David Cronenberg’s The Brood (1979). King’s book features Danny as someone able to call out for help from Dick Hallorann (Scatman Crothers in the film) when needed, as well as read the minds of his parents. The Overlook, a place of psychic trauma, is awakened by Danny’s powers in the novel, and it grows to become a conscious force that corrupts Jack because it wants to feed on the boy. But Kubrick’s film does not represent Danny as having a specific talent; it avoids defining the flashes in Danny’s mind, captured with erratic subliminal editing, and never reveals whether the boy in Danny’s throat, named Tony, is really an imaginary friend or a personification of his psychic talent. Instead, it’s enough to know that Danny is an involuntary receptor of psychic images. He can make no more sense of the pictures-in-a-book than the viewer can of the Overlook Hotel or what exactly happens in the plot. Kubrick has reduced the intricate story and psychological underpinnings of King’s novel to render every aspect somehow ethereal and uncertain, leaving us in a perpetual state of unease and inquisitiveness. The result feels strategic, as though Kubrick intended to give fewer details if only to compel the viewer to make connections of their own.

Similarly, Kubrick affirms only vague allusions to the source and origins of the film’s ghosts, if that’s what they are. They have no stated ambition to acquire Danny by corrupting his father, as they do in King’s book. Their use is limited to a few apparitions, concentrated mostly on the bartender Lloyd (Joe Turkel) and the waiter named Grady. The others, mostly spied by Danny or Wendy in her frantic rush through the Overlook in the climax, consist of random and unexplained images: The murdered Grady twins tell Danny to “Come play with us… forever, and ever, and ever.” A tuxedoed man appears to Wendy with a drink in his hand, a bloody gash down the top of his head, and says, “Great party, isn’t it?” One apparition, donning an animal costume, appears to be fellating a well-dressed man. And the dreaded elevator, with its iconic ocean of blood pouring out from the slowly opening doors, has no logical place in the story—it’s a phantom image whose consequence is never acknowledged. Danny sees the elevator doors opening in his mind, and so too does Wendy, as there’s never a moment when that sanguine tide rolls over her ankles and submerges her feet in red. She seems to have a touch of “the shining,” Hallorann’s name for Danny’s extra-sensory talent. Additionally, each ghost or apparition exists outside of any established mythology embedded into the Overlook by King. They are not representative of a single force or group of spirits that must be addressed by the plot in the manner of an exorcism. Like so many elements of The Shining, the spirit world is indefinite, yet all the more haunting for its uncertainty. Whether they compel Jack to act or not remains debatable, but the threat in The Shining remains the physical presence of the ax-wielding Jack.

Of course, every narrative element broad stroked above cannot adequately portray the uncanny effect of watching The Shining, which is more to the point of this essay. But those who watch the film and demand answers often find themselves confronted with details that could be, and in many cases probably are, continuity errors or coincidences. Is there some hidden meaning in the fact that, in Wendy’s frantic journey through the Overlook, the kitchen knife she carries alternates between her left and right hand? Why does the color of Jack’s typewriter change in the film? And what hidden purpose could the so-called impossible window in Ullman’s office serve, as it should not exist according to the floor plan of the hotel? In all likelihood, these details mean nothing; they doubtless resulted from continuity errors or practical on-set solutions and oversights that occur in the course of every film shoot. Props move, ideas from deleted scenes or rewritten story elements remain conspicuously in the frame, and the layout of the Overlook remains a constant source of confusion. While some of these factors serve as a confrontation to the rational-minded filmgoer, they also drive unjustified beliefs in the “crippled epistemology” of conspiracy theorists. In his monograph for the British Film Institute, Roger Luckhurst wrote The Shining “does to its viewers what the hotel does to its visitors—it makes them shine on things glimpsed that were perhaps never there.”

Kubrick’s reluctance to shed light on basic elements of the story, combined with what could be called mistakes in the filmmaking process, has made room for enduring questions that force the viewer to search for clues and answers. The film is a cryptograph, but the cipher exists only in Kubrick’s head, if at all. The insufficient details of the plot, the wealth of continuity errors left to be second-guessed, and the repetitive visual motifs have led to an overwhelming amount of commentary and close readings among film historians and online commentators. Rodney Ascher’s documentary Room 237 (2012) considers five such theories, ranging from a hypothesis that suggests Kubrick meant The Shining as a confession that he shot the first moon landing for NASA, to the theory that the placement of Calumet baking powder in the film, with its logo of a Native American in a headdress, meant to underscore the theme of genocide in America by the hands of European colonists. Although it is not the ambition of this essay to dismiss any interpretation, the theories continue and remain part of a more significant subjective process of reading film. Every moment of The Shining can be pored over, debated, and considered for what Kubrick intended, certainly more than most films released by a major Hollywood studio like Warner Bros. But the real purpose of the film seems to be less an articulated reading; instead, it acts a designer puzzle with no answer, a Rorschach test that, on its own, remains empty until the viewer fills it up.

Kubrick understood that film texts are read; that is how they form meaning. This concept had consumed the director since he sought to tap into the audience’s subconscious mind with 2001: A Space Odyssey, and then continued to challenge filmgoers with the elusive meanings of A Clockwork Orange (1971) and Barry Lyndon (1975). It is the role of the spectator to interpret the film regardless of the filmmaker’s intent, and Kubrick had become increasingly interested in this concept. Theorist and critic Christian Metz argued in terms of semiotics that the spectator “constitutes the cinema signifier,” that the viewer arrives at the film’s meaning, both in terms of the surface text and its deeper meanings, through an instant, impulsive, and sometimes an intellectual process of interpretation. The viewer, then, is an active spectator who determines the meaning of the film through their understanding of its language. To achieve this, the viewer must negotiate constant stimuli within and without the frame: the juxtapositions of one image after another in a scene or sequence through editing; the use of music; the placement of specific details within the frame; the choices of camera angle, color, plot, performance, and countless other grammatical specifics to the medium. Each of these elements of cinematic structure and syntax could hold a thousand possible meanings for the viewer. Then the individual could arrive at any number of meanings depending on their interpretation. As a film object, the text means nothing without the viewer’s readership. “A text (a book, a film, a painting) only comes into existence in the act of ‘reading’ it,” wrote scholar Patrick Phillips. “In this way the reader of the text is, in a way, simultaneously its creator.”

Filmmakers can hope to guide interpretation by employing a transparent and intentioned film grammar, based on a whole history of the ever-developing language of film and recognition of how that language has been interpreted and progressed in the past. In his formative book Signs and Meaning in the Cinema, Peter Wollen argues that both the formal elements of a film object (the signs) and its signified expression (the meaning) are inextricably connected. “There is the rudiment of a natural bond between the signifier and the signified,” Wollen wrote, acknowledging that, similar to the development of linguistic models, commonalities exist within the symbols of filmmaking—certain associations that most viewers, but not all, will make. The best a filmmaker can hope for, it seems, is to tap into the shared, interpreted language of the collective majority of their audience. However, the personal histories and cultural learning of each individual informs their perception. Metz argues that the “plurality of readings is associated with the plurality of codes which give form to the film.” In other words, interpretations will vary based on perception, and perception is a subjective state as multifaceted as human beings are from one another. Metz also believed “the practice of cinema is only possible through the perceptual passion: the desire to see.” As viewers, we have an innate desire to watch a film like The Shining and understand it, to extrapolate its meaning from our own experiences and interpretations. Accordingly, Kubrick’s approach to The Shining may not intend a straightforward intellectual understanding of its meaning, even as it invites readership.

The way The Shining uses film language relates to subconscious connections in the mind. It is the way that some free verse poets create associations through unconnected thoughts and words, arriving at an unconscious meaning far less straightforward than reading a series of scenes to determine what occurs in the plot. In interviews with French critic Michel Ciment and others from the period, Kubrick talked about being inspired by Arthur Schnitzler’s Rhapsody: A Dream Novel from 1926, a story that follows a Viennese doctor transitioning between states of consciousness and dreams as he pursues his erotic fantasies. The director would later adapt the book into Eyes Wide Shut in 1999. Kubrick and Sigmund Freud alike have compared the experience of the cinema to dreaming, where visual impressions make connections in the mind, which is another way of expressing the cognitive process of meaning-making described by Metz, Phillips, and Wollen. Kubrick was drawn to the ambiguities of cinema, its ability to capture a state of waking dreams as an impressionist painter would capture light and form in unfocused brushstrokes. Kubrick doubtless sought to evoke this quality with The Shining, more so than any other film in his oeuvre, even his comparatively literal adaptation of Eyes Wide Shut. Though viewers and Kubrick enthusiasts will debate about the intentionality of The Shining’s rich symbolic underpinnings, there exists an undeniable compulsion on the part of the film’s audience to read into the formal language beyond the surface text, as the film has willingly engaged the fantasies of the film-reader.

How Kubrick achieved his maze of the mind remains a matter of film history and some speculation, especially when it comes to questions about the intentionality of his continuity and logistical errors. Typical for Kubrick, it took the meticulous filmmaker several years to complete his adaptation of King’s book. He chose the material after the disappointing performance of Barry Lyndon in 1975, a film that failed to strike a chord with a larger, more commercial audience. It has been widely suggested that The Shining was Kubrick’s attempt to reach the stratosphere of popular culture, using King’s name as a launchpad, and that Jack’s repeated statement on the typed page—“All work and no play make Jack a dull boy”—somehow reflected this. Moreover, it takes no stretch of the imagination to see a parallel between Jack Torrance and Stanley Kubrick. Torrance is a blocked writer with personal demons to overcome, and he seeks a reclusive spot for the winter to regain himself and complete work on his next writing project. Similarly, Kubrick increased his reclusiveness around the same time. He had hired his extended family members and close friends to contribute to his productions; he had relocated to a remote country manor far removed from his previous home in London. Some would argue that Kubrick even resembled his first and only choice to play Torrance, Jack Nicholson, both of whom appear ragged and psychologically drained on the set of The Shining, as evidenced in Viviane Kubrick’s short documentary about its making. They both could strike an intimidating gaze, sometimes called a “death stare” or the “Kubrick Stare,” with their downturned chin, mouth creepily agape, and a prominent brow, under which eyes peer out into nothingness.

The Shining was filmed on MGM’s British lot at Elstree Studios, where the interiors of the Overlook Hotel, among them a massive and functional set-piece of the Colorado Lounge, and the entire hedge maze were constructed for the production. The hotel itself is not a real-life location, though the Timberline Lodge in Oregon inspired it. Its life-size interiors and some of its exteriors were built in an entirely convincing environment on soundstages. The closed set was also a believable and livable space, housing much of the production’s cast and crew as an actual hotel would. But the soundstages did not precisely mirror the hotel as outlined in the film, which accounts for several of the breaks in layout and visual logic that appear throughout the picture—especially in scenes that follow Danny on his big wheel tricycle on the floor of Room 237, where the Colorado Lounge can be briefly glimpsed in the background. In effect, Kubrick was replicating the approach of German expressionist filmmakers from F.W. Murnau to Robert Weine, who built their sets from the ground up with cockeyed angles and dark shadows to reflect the inner corruption of their characters. The shooting spaces of The Shining, free of the distractions that would plague a production in a working hotel, allowed the director and actors to embrace what Kubrick called their “psychic energy.”

The mood on the set, eyed in Viviane Kubrick’s peek-of-a-film, reflected the dynamic of the screen story. Nicholson, well versed in roles that critiqued masculinity (see Five Easy Pieces, 1970), brings Jack Torrance layers of escalating madness and cruelty. Kubrick seemed to respond to Jack’s behavior, treating Duvall with harshness and impatience in one scene when she fails to hit her mark on cue. Even Duvall’s character had been cut down by Kubrick, reducing Wendy to a mere woman in danger instead of a three-dimensional character. Though Duvall insisted such treatment fostered a better performance, the lingering trauma of the experience remained. Still, Kubrick was constantly rewriting his scripts on the set and never published his initial drafts; no hard evidence remains to contrast what was initially intended and what appears onscreen. In the face of such widespread speculation and theorizing about The Shining’s meaning, it is important to remember that Kubrick’s scripts were a living document, ever-changing and fluid. He was continually coming up with new ideas, making alterations at his typewriter, and adding pages to the script, just as Jack punches away at his keys to bring his manuscript to life. In the book Stanley Kubrick, Director: A Visual Analysis, the authors note that Kubrick’s shooting script “seems increasingly to resemble a talisman rather than a set of imperatives.” The performers, then, had to be ready to improvise, learn lines on the go, and take specific direction at a moment’s notice, outside of any preparatory effort. The six-month shoot became a collaborative effort between the director and his cast, albeit dependent on whether Kubrick could find the moment he was searching for amid his painstaking need for repeated takes. This hardly sounds like the creative environment where one filmmaker carries out his elaborate, precalculated design to achieve a singular meaning.

There were also technical hills to overtake. Shooting within a tactile hotel set-piece, which did not have detachable edifices such as walls and floors to hide cameras, presented a challenge. It would have been impossible for Kubrick to lay down tracks to shoot scenes when Danny pedals his tricycle down long corridors before arriving at the same place he started. The solution? The Steadicam, invented by Garret Brown in 1975 to supply long, fluid takes with the use of a body-mounted harness that makes the frame seem weightless. Serving as a camera operator under the guidance of cinematographer John Alcott, Brown glides the camera with a wraithlike balance rarely seen in the cinema at that point. Before The Shining’s release, only a few films used the Steadicam—including Hal Ashby’s Bound for Glory, John Schlesinger’s Marathon Man, and John G. Avildsen’s Rocky, all released in 1976. But Kubrick needed the technique to work in the limited space of the hallways and rooms of the Overlook sets, as well as the passageways of the hedge maze. Such cramped areas determined the form, inhabiting the space between his characters within their environment, such as when Jack pursues Wendy across the Colorado Lounge and up a stairway, and the camera moves with them in a shot reverse shot. More often, the Steadicam trails a character down a long, narrow passage. When Danny runs to escape his father in the snowy hedge maze climax with the camera trailing behind, and the shot looks back at Jack, the camera’s placement and movement create the sense of both moving with the characters and feeling pursued by Danny’s murderous father.

The Steadicam effect has a far more ethereal quality than the Panaglide technology employed in the POV opening of John Carpenter’s Halloween a year earlier. The camera seems to float, almost like a ghost, and engage its subject with a spooky directness. The subject of nearly every shot is centralized in the frame, using the same one-point linear perspective employed by Leonardo Da Vinci in his mural of The Last Supper. The lines of rooms, hallways, and mazes direct the eyes toward a focal point, usually the subject in the frame, imbuing it with visual emphasis that invites speculation. Kubrick’s use of perspective enhances the perceived importance of each character or object, while also drawing our attention away from smaller, possibly important and subliminal details within the frame. They are not as subliminal as the brief shots of the bloody elevator or the ghostly murdered twins inserted into Danny’s vision, but they are subliminal in the sense that they seem intentional, although they do not draw the camera’s attention. For instance, the presence of Native American motifs throughout the hotel has been read as significant to the meaning of The Shining. The Overlook is a site of imperialism and genocide, erected over a native burial grown by European colonists, who then used the motifs of the people they eradicated for interior decoration. The casualness of this atrocity should not be dismissed. Regardless, could it not be that Kubrick knew his concentration on characters in the focal point of any given scene would instantly pull the curious viewer’s gaze away from the very spot that the geometric lines of the rooms, hallways, and architecture tell us to look?

Given the on-set improvisations, constant rewriting, and how the spatial limitations of the sets dictated the form, the viewer of The Shining could not be blamed for questioning the extent of Kubrick’s grand design. The film is both less and more than what those who maintain wild theories about Kubrick’s intentions believe it to be. Less, in the sense that Kubrick’s spontaneity implies that he did not enter into the realm of The Shining with every detail prefigured, as some have argued; more, in the sense that the film-reader, whose subjectivity determines the film’s meaning, has an abundance of half-developed and uncertain contexts to search within and interpret. The film has a rich and endless string of patterns, sometimes literally so, inside of which the film-reader can lose themselves. It’s all the more paradoxical to the traditions of the genre in this respect, as long before the perpetual daylight of Midsommar (2019), Kubrick shot his horror film in the full illumination of a functioning hotel—inside the well-lit kitchen, bedrooms, hallways, and ballrooms of the Overlook, where the details were entirely visible if not conspicuously placed for us to find. But with everything illuminated, Kubrick does not tell the viewer where to look to decode his clues, if indeed they exist. Quite infuriatingly so, he demands that the viewer work at his film—and for audiences accustomed to the spoon-feeding of standard horror fare from the era, such a challenge could be maddening. Luckhurst wrote that the film is “high art and low culture, subversive yet utterly contained… seemingly destined to please no one.”

When The Shining debuted in 1980, it followed a lengthy promotional campaign and countless features in print about its extended production. Critics at the time had become suspicious of filmmakers indulging their whims with protracted shoots and elevated budgets. After all, 1980 was the same year as Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate, an infamous bomb that forced Hollywood to reconsider giving a proven filmmaker a blank check to make their dream project. With The Shining, critics reacted to the months of trailers that had showcased haunting imagery, such as the Overlook’s elevator doors opening to unleash a wave of blood and Kubrick’s pronouncement that he had made the scariest film ever. The critic for Sight & Sound called it a “trivial project,” and Pauline Kael complained in The New Yorker of the distancing effect found in Kubrick’s obsession with filmmaking technology and technique. After the New York premiere, Kubrick cut his 146-minute version down by more than twenty minutes: a few weeks after the film had opened in the U.S., he cut two minutes; just before the London debut, he cut another twenty-five minutes. The two minutes removed from the U.S. version consist of an alternate ending where Ullman, the hotel manager, greets Wendy in her hospital bed and informs her that her husband’s body was never found. Among the larger sections removed from the U.K. cut were the scenes with the doctor who talks to Danny after his seizure in Sidewinder, some of Jack’s misogynistic words about Wendy, and several of the supernatural elements from the latter half of the picture. Much like King, who will sometimes tinker with a single concept over several short stories, novellas, and books, Kubrick would rethink his films, sometimes after their debut.

Once again, Kubrick’s need to rethink his work, even after it was released theatrically, underscores that his designs were discovered in the process of its making, and perhaps not schematized in advance to the extent suggested by many fervent fans. Still, if there is a thematic current to The Shining, it exists in Kubrick’s desire to create a maze using imagery drawn from loaded icons—fairy tales, pop-culture, myth, history, and countless other sources discovered by the detail-oriented viewer. Consider the cultural touchpoints of a single scene, when Jack corners Wendy and Danny in their living quarters with an ax: Jack announces, “Wendy, I’m home,” in the manner of Desi Arnaz in I Love Lucy. Terrified, Wendy and Danny lock themselves in the bathroom. Jack approaches the door in character as the Big Bad Wolf. “Little pigs, little pigs, let me come in,” he says. In the next moment, he crashes through the door to deliver the line “Heeeeere’s Johnny!”—the familiar introduction from Johnny Carson’s The Tonight Show. The commonplace domestic setting of these references is countered by the violent situation, creating a sense of twisted unease and familiarity. Such disorienting contrasts are evident throughout The Shining, begging the viewer to assume that Kubrick calculated their placement. With this in mind, the Overlook’s impossible floor plan could be less a result of the necessities of filmmaking and more an intentional choice to reflect the Gothic story’s need to disorient the viewer.

After these chillingly familiar yet unresolvable aspects of the film, the ambiguity of its ending leaves the viewer in a permanent state of restless confusion. In a series of slow movements and fades, the last images of The Shining display a wall of historical photographs. Jack appears in a black-and-white shot taken at the July 4th ball from 1921, echoing Delbert Grady’s fearsome line to Jack, “You are the caretaker. You’ve always been the caretaker. I should know, sir; I’ve always been here.” Has Jack been consumed by the Overlook and appropriated into its story by supernal means? Perhaps Jack’s mind, the mind of a depressive and alcoholic, has been emptied. Somewhere between the mental vacancy of his writer’s block and his mindless insomnia, between states of oversleeping and staying up too late, his mind is consumed by the Overlook. Maybe he finally accepts being occupied by the hotel when he remarks, “I’d give my goddamn soul for just a glass of beer.” Or is Jack caught in some nightmarish loop of fate destined to repeat itself? In the photo, Jack holds a piece of paper that the man behind him restrains him from showing. What does it say? “Help me” or “Let me out” perhaps? Any speculation may be pointless, as the ending was necessitated by a massive fire that brought the Colorado Lounge set to the ground and cost the production $2.5 million. Would Kubrick have made an ending closer to the one in King’s book—where the pressure in the neglected boilers causes the Overlook to explode—had his set not burned down? We can only speculate, as the conclusion proves as open-ended as almost every aspect of the film.

The Shining offers an enigma from which there is no escape, and with that in mind, the essential metaphor of the film becomes the hedge maze. Kubrick conceived of the maze as a necessary replacement for the silly living topiaries of King’s novel, and he even lost himself in the walls of the real maze when the film’s crew challenged him to enter. Kubrick harbored a lifelong fascination with the Minotaur of Greek mythology, the beast who stalks those who enter the Labyrinth of Crete. Jack serves as a stand-in for the Minotaur, and in one scene, he looms over the maze, looking down in a shot that transitions from a model to a bird’s eye view of the actual maze with Wendy and Danny inside. Perhaps Kubrick intended Danny as a Theseus figure, one who guides the Jack-Minotaur to his cold death inside the hedge maze. And could Danny’s ability to elude Jack be hinted in his love for Road Runner cartoons, which Danny watches more than once on television in the film? By extension, in the realm of Looney Tunes symbolism, Danny’s nickname, Doc, is a reference to Bugs Bunny’s saying, “What’s up, doc?” Of course, Bugs Bunny was an expert at evading everyone from Elmer Fudd to Daffy Duck. Just as the Road Runner avoided becoming lunch for Wile E. Coyote, Danny avoids his Minotaur-father in the maze in the finale. Then again, this line of thinking demonstrates how easily the viewer can make logical, plausible hypotheses through detail-oriented readership and stretch them into pure conjecture that, for instance, somehow encompasses both Greek mythology and Looney Tunes.

Kubrick turns the viewer of The Shining into a Jack-like figure—a filmaholic whose mind has been emptied out only to be filled with stimuli, all arranged and orchestrated by Kubrick, through which we access our subconscious film-reader. An exhaustive, and exhausting, degree of contexts and interpretable details threaten to distract from the more substantial consideration, which is the genius of Kubrick’s manipulation of his audience. He has caught the spectator of The Shining in a continuous loop, much like Jack, who both feels at home in the Overlook Hotel and like he’s been there before. “We all have moments of déjà vu,” he tells Wendy, “but this was ridiculous.” The viewer who is drawn back to The Shining every few years to reassess its secrets can relate. Kubrick’s arrangement of contexts and details does not point to a single meaning, but in stepping back and recognizing how the film functions as a maze, one will see a layering effect that makes aspects of the film familiar but elusive, and therefore frightening because their precise meaning evades any certainty or intellectual understanding. The terrifying aspect of The Shining, and its most enduring quality, is how Kubrick has trapped us in his cinematic maze to search without hope of ever discovering an adequate answer outside of our own making.

Bibliography:

Chion, Michel. Kubrick’s Cinema Odyssey. British Film Institute, 2001.

Hardin, Robert. “The Crippled Epistemology of Extremism.” Political Extremism and Rationality. A. Breton et al., editors. Cambridge University Press, 2002, pp. 3-22.

LoBrutto, Vincent. Stanley Kubrick: A Biography. D.I. Fine Books, 1997.

Luckhurst, Roger. The Shining. BFI Film Classics. British Film Institute, 2013.

Metz, Christian. “The Imaginary Signifier.” Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings (Third Edition). Mast, G. & Cohen, M. (Editors). Oxford University Press, 1985.

Nelson, Thomas Allen. Kubrick, Inside a Film Artist’s Maze. New and expanded ed. Indiana University Press, 2000.

Philips, Gene D., editor. Stanley Kubrick: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi, 2001.

Phillips, Patrick. “Spectator, Audience and Response.” An Introduction to Film Studies (Third Edition). Nelmes, Jill. (Editor). Routledge, 2003.

Sperb, Jason. The Kubrick Facade: Faces and Voices in the Films of Stanley Kubrick. Scarecrow Press, 2006.

Walker, Alexander, et al. Stanley Kubrick, Director: A Visual Analysis. Rev. and expanded. Norton, 1999.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review