The Definitives

The Seventh Seal

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Swedish filmmaker Ingmar Bergman made The Seventh Seal in 1957; however, its allegorical power has since ascended into the realm of timelessness. Closely developed from his one-act play Painting on Wood, first performed at Sweden’s Radio Theatre in 1954, the film foundationalizes the widespread, yet narrow view of Bergman as an intellectual suffering from the ongoing attacks of his own inner demons. A singular expression of the director’s own ponderings on the nature of faith, mortality, and love, the profound film employs ideas and visuals so iconographic and transcending, they rise above the limitations of the medium. Already Bergman’s name had garnered the attention of world cinemagoers with his blithe 1955 comedy Smiles of a Summer Night, but the director’s quintessential persona was not established until two years later. The Seventh Seal propelled Bergman into the radar of art film enthusiasts the world over, having won the Special Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival the year of its release, as well as other prestigious awards throughout the European festival circuit. In the subsequent decades, his more than fifty motion pictures comprised one of the most impressive filmographies for any director, because each film maintains his personal style, tone, and lasting themes—signatures that were concreted by this, his most popular and existential motion picture.

Set during the Middle Ages, The Seventh Seal begins with an ethereal rendition of the Latin hymn Dies Irae playing under a narrator’s voice that reads from the Book of Revelations: “And when the Lamb opened the seventh seal, there was silence in heaven about the space of half an hour. And the seven angels who had the seven trumpets prepared themselves to sound.” There to find the answers hidden behind God’s final seal, now broken, Knight Antonius Block (Max von Sydow) awakens on a stone covered beach, and having returned from the Crusades a failure, along with his contemptuous squire Jöns (Gunnar Björnstrand), he finds Death waiting for him. Enshrouded in a black cloak, the pale-faced Death (Bengt Ekerot) appears in a soundless materialization. Block contends to delay his demise and challenges Death to a game of chess, the film’s most unforgettable piece of imagery and most venerable narrative fixture. Throughout the ensuing events they return to their game, Block hoping to survive long enough against his experienced opponent to gain some proof of either God or Satan, or at least commit one dignified act before The End.

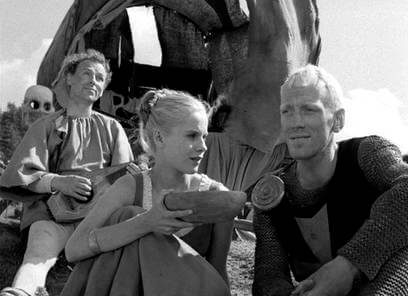

After ten years in the service of God, surviving the horrors of his perilous campaign, Block feels some answers are owed to him. He and Jöns travel to a nearby village, on the way discovering that The Black Death has polluted the countryside. In the village church, Block visits confession and expresses his innermost atheistic doubts: “What is going to happen to those of us who want to believe but cannot? And what is to become of those neither want to nor are capable of believing?” Death receives Block’s questions much to his advantage, and upon exposing this trickery, Block resolves to continue steadfast against his opponent for the sake of his own curiosity. While Block and Jöns continue their journey, Bergman intercuts with the quiet purity of three traveling performers, the couple Jof (Nils Poppe) and Mia (Bibi Andersson), and their company leader Skat (Erik Strandmark). First shown resting in a peaceful sleep on tranquil grass, they present the antithesis of Block’s awakening: Slowly Jof rises, stretches his body, rinses his mouth, and then turns to see a vision of the Virgin strolling with her boy. A sort of seer, Jof’s dreams are waved off as fanciful by Mia. Untroubled by burdens of faith, these innocents bound by love and endurance do not fear Death. The two opposing troupes plug along on their respective pilgrimages, the one on a trek to understand the greatest questions of them all, the other not concerned in the least about questions, rather content with a carefree way of life. Regardless of their objectives, Death follows close behind both parties.

After ten years in the service of God, surviving the horrors of his perilous campaign, Block feels some answers are owed to him. He and Jöns travel to a nearby village, on the way discovering that The Black Death has polluted the countryside. In the village church, Block visits confession and expresses his innermost atheistic doubts: “What is going to happen to those of us who want to believe but cannot? And what is to become of those neither want to nor are capable of believing?” Death receives Block’s questions much to his advantage, and upon exposing this trickery, Block resolves to continue steadfast against his opponent for the sake of his own curiosity. While Block and Jöns continue their journey, Bergman intercuts with the quiet purity of three traveling performers, the couple Jof (Nils Poppe) and Mia (Bibi Andersson), and their company leader Skat (Erik Strandmark). First shown resting in a peaceful sleep on tranquil grass, they present the antithesis of Block’s awakening: Slowly Jof rises, stretches his body, rinses his mouth, and then turns to see a vision of the Virgin strolling with her boy. A sort of seer, Jof’s dreams are waved off as fanciful by Mia. Untroubled by burdens of faith, these innocents bound by love and endurance do not fear Death. The two opposing troupes plug along on their respective pilgrimages, the one on a trek to understand the greatest questions of them all, the other not concerned in the least about questions, rather content with a carefree way of life. Regardless of their objectives, Death follows close behind both parties.

Using exterior locations and a minimum of effects, rather clever editing and ingenious directing, Bergman shot the picture over 35 days without much of a budget. Despite the short time allotted and meager financing available for his production, Bergman’s film resonates with striking singularity, his scenes perfectly described to build a thesis saturated to every last detail with his personal touch. Cinematographer Gunnar Fischer’s camerawork tells the story in high contrast black and white, capturing iconic and much copied compositions each more memorable than the last, and framing that creates a filmic portfolio worthy of still photography. Even amid the grim setting and substantial subject matter, the film’s beauty overwhelms. An exercise in allegorical fantasy, certainly not realism, The Seventh Seal’s dialogue and visual rhetoric relies on an omnipresent sense of the theatrical, which communicates the poetry of Bergman’s prose and surpasses the limitation of both the stage and cinema. Grand, soul-searching conflicts are described with imposing ornamentation rooted in Christian symbolism, ranging from Death himself, to religious processions, to the decorative Medieval artwork appearing throughout the picture. The dialogue feels heavily dramatic, written with all the splendor and control of epic poetry. As the theatrical discourse flows outward through the actors’ emotive delivery, above all Von Sydow’s, the disciplined pace supports the absolute sincerity and concentration of the film’s tone. These qualities span most Bergman films, and in addition to their frequent imitation, have become the signifiers of the greatest auteur to labor almost exclusively in art-house film.

Like a textbook, the film catalogues those pensive themes that would become entrenched within Bergman narratives, demanding the adjective Bergmanesque for his aspiring followers. He made his name by pushing characters to pursue his particular brand of introspection, relying on his private and professional experiences to inspire their spiritual curiosity. His characters frequently struggle for self-understanding when positioned next to a bigger picture, be they individual battles with their place in the community; the awareness of the body in relation to, or not, to the mind; the mutual love and hatred for nature; and the individual’s relationship or belief in the supernatural, meaning God or ghosts or some other unearthly force. Whatever the basis of the central conflict, it requires self-reflection on the part of the protagonist.

Like a textbook, the film catalogues those pensive themes that would become entrenched within Bergman narratives, demanding the adjective Bergmanesque for his aspiring followers. He made his name by pushing characters to pursue his particular brand of introspection, relying on his private and professional experiences to inspire their spiritual curiosity. His characters frequently struggle for self-understanding when positioned next to a bigger picture, be they individual battles with their place in the community; the awareness of the body in relation to, or not, to the mind; the mutual love and hatred for nature; and the individual’s relationship or belief in the supernatural, meaning God or ghosts or some other unearthly force. Whatever the basis of the central conflict, it requires self-reflection on the part of the protagonist.

The Seventh Seal captures these themes in total, presenting the mold from which every subsequent Bergman film would be balanced against. Consider how Block abandons his knightly crusade to find himself on a plague-ridden terrain, questioning God, competing with Death for his own mortality. In this most basic plot description, Bergman’s existential hero weighs every potential conflict from his environment to the philosophical. Accordingly, Bergman’s film acts as a stream of questions through the guise of various emblematic characters. Block remains idealistic toward all things, romantic in his belief that life should have a specific purpose, embracing his doubt to further his knowledge and achieve self-understanding. Jöns is more of a realist, even sarcastic and critical at times, aware that such questions can and probably should be asked, but too much of a pragmatist to ask them himself. Jof and Mia are simpletons, representative of the masses, enjoying life at face value without the need to define.

Bergman makes his film very plainly about opposites, his characters inhabiting contrary fields within his developed landscape. Block presents the steadfast knight dedicated to duty and meaning, to finding his place, if one exists, amid the dogmatism of the Church. At one point he raises his hand and confirms, “This is my hand. I can move it, feel the blood pulsing through it. The sun is still high in the sky and I, Antonius Block, am playing chess with Death.” If only God could be identified so plainly, as defining things allows him to gain the knowledge he feels he deserves after a lifetime of service. Whereas Jof and Mia enjoy the purest of true love—they are frivolous and happy, and together they remain so until the end. They are the hope of humanity. They speak of Mikael’s future, and they regard Death as no more than an empty theater mask used in their routine, part of an elaborate act, no less. Scenes reciprocate between Block and the happy couple, alternating the perils of mortality with the pleasantry of life. This motif of opposites, and the absolutism of the film’s thematic and representational positive and negative spaces, find a further emphasis on the black and white pieces of Death and Block’s reappearing chessboard.

Bergman makes his film very plainly about opposites, his characters inhabiting contrary fields within his developed landscape. Block presents the steadfast knight dedicated to duty and meaning, to finding his place, if one exists, amid the dogmatism of the Church. At one point he raises his hand and confirms, “This is my hand. I can move it, feel the blood pulsing through it. The sun is still high in the sky and I, Antonius Block, am playing chess with Death.” If only God could be identified so plainly, as defining things allows him to gain the knowledge he feels he deserves after a lifetime of service. Whereas Jof and Mia enjoy the purest of true love—they are frivolous and happy, and together they remain so until the end. They are the hope of humanity. They speak of Mikael’s future, and they regard Death as no more than an empty theater mask used in their routine, part of an elaborate act, no less. Scenes reciprocate between Block and the happy couple, alternating the perils of mortality with the pleasantry of life. This motif of opposites, and the absolutism of the film’s thematic and representational positive and negative spaces, find a further emphasis on the black and white pieces of Death and Block’s reappearing chessboard.

Detractors wary of Bergman’s allegories suggest he unnecessarily disguises questions about God through his historical setting and metaphoric imagery. Unabashed confrontation of the audience in a modern setting, however, results in more challenging material for the viewer; moviegoers often disconnect when modern cinematic environments so clearly try to make a decisive and difficult connection. Bergman films like Persona (1966) and Wild Strawberries (1957) that do not enclose their meaning inside figurative backdrops are more demanding. By disguising his most aggressive argument, his filmic question, within the Medieval setting, Bergman lightens the intellectual load on the viewer and makes these questions apparent but not brazen attacks on his audience’s modern ideologies. Of course, Bergman absolutely means to challenge his audience, but The Seventh Seal achieves this in the most clever, illusory way of any Bergman film.

Like many directors, Bergman saw film as an extension of reality. “Film must go outside realism,” he argued, “outside the usual descriptions of reality that surround people.” Setting and period therefore play crucial roles in devising the director’s form of questioning within The Seventh Seal, making the picture more accessible as an allegory to be sure, but also camouflaging its modern resonance behind veiled, atmospheric, and symbolic locales that service his commentary. His 1960 film The Virgin Spring, based on a Swedish ballad Töres dotter i Wänge, also uses the Medieval period to help populate the setting with figurative and always relative situations, being about a father who considers his faith when faced with the rape and murder of his daughter, how his desire for savage retribution outweighs his pious devotion. That the director asks these questions in such a specific setting allows him to clearly communicate the intended function of his film, seasoned with severe metaphors to illustrate his eternal questions about God and death, and visually arouse his contempt for the church. More effective filmmaking than his characteristically staid pictures with similar themes yet in contemporary settings, these films of The Dark Ages prove more accessible, escapist, and deceptively thought-provoking.

Like many directors, Bergman saw film as an extension of reality. “Film must go outside realism,” he argued, “outside the usual descriptions of reality that surround people.” Setting and period therefore play crucial roles in devising the director’s form of questioning within The Seventh Seal, making the picture more accessible as an allegory to be sure, but also camouflaging its modern resonance behind veiled, atmospheric, and symbolic locales that service his commentary. His 1960 film The Virgin Spring, based on a Swedish ballad Töres dotter i Wänge, also uses the Medieval period to help populate the setting with figurative and always relative situations, being about a father who considers his faith when faced with the rape and murder of his daughter, how his desire for savage retribution outweighs his pious devotion. That the director asks these questions in such a specific setting allows him to clearly communicate the intended function of his film, seasoned with severe metaphors to illustrate his eternal questions about God and death, and visually arouse his contempt for the church. More effective filmmaking than his characteristically staid pictures with similar themes yet in contemporary settings, these films of The Dark Ages prove more accessible, escapist, and deceptively thought-provoking.

Through his epochal filter, Bergman’s depiction of the church, especially the house of the Middle Ages and the people following its dogma, shows little respect to say the least. His treatment is fuelled by a longstanding personal disdain against the institution, drawn from his youthful conflicts with his doctrine-obsessed chaplain father. Bergman believed that, relying on the lack of education, weakness, and general gullibility of its flock, the church gathers its supporters and destroys the soul from within itself like a disease. And so, the plague in the film spreads across the lands while the religious zealots call it the end of days—images inspired by Bergman’s early life, when he watched as his father spent days burying the dead from a Spanish flu epidemic.

In the church scenes, the mural painter tells Jöns, “Remarkably, the poor wretches think that the plague is a punishment from God. Crowds of ‘sinners’ wander the land whipping themselves and others to please the lord.” Endorsed by the highest of religious hierarchy, a parade of flagellants lash themselves and spray blood, remove their hair, and tear at their flesh in the name of God, their actions causing The Black Death to spread. Bergman’s portrayal of this self-afflicting spectacle was heralded by Medieval paintings, modern historical analysis, and in time parodied by Monty Python and the Holy Grail. Devotees wail and convulse in the streets to be saved, begging for mercy from “The Almighty,” broadening the reach of the very plague that carves them away. Ironically perpetuated by those who fear it, the flagellants and church enthusiasts propel themselves toward the Apocalypse, which Bergman uses as a sign of the senselessness of their beliefs and following. Why else would his version of Death be adorned with priestly robes? Accordingly, Bergman paints the clergyman Raval (Bertil Anderberg) as a wolf in saint’s clothing, and first shows the holy man robbing the corpse of a raped servant girl. Jöns captures Raval and rightly accuses him of sending Block on Crusade so that he would be free to corrupt and pilfer without consequence. Jöns sends him off alive, but with a warning. And later, when Raval spins hatred for Jof among drunkards at the village tavern, Jöns saves the actor from ridicule and thrashes the cleric’s face as promised. As additional poetic justice, Bergman leaves Raval stricken with the very plague that he has helped spread through the fear and devotion wherefrom his kind draw their power. Raval finally cries out to escape Death, although he preached that humanity would only find absolution in the afterlife.

In the church scenes, the mural painter tells Jöns, “Remarkably, the poor wretches think that the plague is a punishment from God. Crowds of ‘sinners’ wander the land whipping themselves and others to please the lord.” Endorsed by the highest of religious hierarchy, a parade of flagellants lash themselves and spray blood, remove their hair, and tear at their flesh in the name of God, their actions causing The Black Death to spread. Bergman’s portrayal of this self-afflicting spectacle was heralded by Medieval paintings, modern historical analysis, and in time parodied by Monty Python and the Holy Grail. Devotees wail and convulse in the streets to be saved, begging for mercy from “The Almighty,” broadening the reach of the very plague that carves them away. Ironically perpetuated by those who fear it, the flagellants and church enthusiasts propel themselves toward the Apocalypse, which Bergman uses as a sign of the senselessness of their beliefs and following. Why else would his version of Death be adorned with priestly robes? Accordingly, Bergman paints the clergyman Raval (Bertil Anderberg) as a wolf in saint’s clothing, and first shows the holy man robbing the corpse of a raped servant girl. Jöns captures Raval and rightly accuses him of sending Block on Crusade so that he would be free to corrupt and pilfer without consequence. Jöns sends him off alive, but with a warning. And later, when Raval spins hatred for Jof among drunkards at the village tavern, Jöns saves the actor from ridicule and thrashes the cleric’s face as promised. As additional poetic justice, Bergman leaves Raval stricken with the very plague that he has helped spread through the fear and devotion wherefrom his kind draw their power. Raval finally cries out to escape Death, although he preached that humanity would only find absolution in the afterlife.

Now together, the two groups of travelers converge on a hillside for a calm rest, where Block thinks of his wife, who far away in their castle waits for her husband to return. Into the forest on the road home, along a trail ripe with scenes of a witch burning and encounters with Death, Block continues to out-maneuver his opponent on the chessboard, always asking his questions that inevitably lead to more questions. Death asks why he keeps asking, knowing no answers will come? Because he must. When Block loses his queen in the game, however, all at once Jof sees Death and rushes Mia into the woods to escape. In a final effort toward redemption, Block distracts Death from the runaways by brushing the pieces off the board with his cloak. Now the game is over. Resigned to his fate along with his remaining companions, Block finally reaches his empty castle, the walls barren and bleak. His wife Karin (Inga Landgré) seems to understand explicitly what will come as she tosses one last log onto the fire. Regretful yet compliant faces all, the group of travelers listen as Karin reads from the Book of Revelations, her words interrupted by the three knocks that suddenly sound throughout the castle. Death is at their door. Ever the realist, Jöns tells Block to appreciate his last breath of life, to “feel the immense triumph of this final moment when you can still roll your eyes and wiggle your toes.” And with that, Jöns helps the others to welcome death. In the final frames, Jof looks into the morning light and sees in the distance the silhouettes of Block, his companions, and Death dancing on the horizon. Mia laughs off his claims as more fanciful visions, and together with Mikael they walk off to a nearby seashore.

The film’s most surprising and joyous reading rests within the innocence of Jof and Mia, their simplicity of purpose, and their undemanding, sophisticated ease in love. The scene after the village, where Block reclines on the hillside with the couple, imbibes a bowl of fresh milk and strawberries, and enjoys the clarity of the moment speaks to the possibility of love and freedom, away from the confining boundaries of the church and the questions they force a thinker to ask. Serene and hopeful, this moment encompasses the underlying and unexpected optimism in Bergman’s film. “Love is the blackest of all plagues. And if one could die of it, there would be some pleasure in love. But you almost always get over it,” Jöns reflects. “If everything is imperfect in this imperfect world, love is the most perfect in its perfect imperfection.” Such positive and indeed romantic sentiments seldom come from a pragmatist like Jöns, or a misanthrope like Bergman, but they survive through Block’s lamentations and flourish in the scenes with Jof and Mia. Cerebral though Bergman’s films may be, the director takes a realist’s stance on love, acknowledging the effort (and naiveté) it requires; yet he insists that attaining love often presents a person’s sole purpose to keep going. He grasps the potential for complication with love, and when relationships are his central theme—like in the aforementioned Smiles of a Summer Night, or Scenes from a Marriage (1973) and its sequel Saraband (2003)—Bergman often resolves that the toils are worth the plunder.

The film’s most surprising and joyous reading rests within the innocence of Jof and Mia, their simplicity of purpose, and their undemanding, sophisticated ease in love. The scene after the village, where Block reclines on the hillside with the couple, imbibes a bowl of fresh milk and strawberries, and enjoys the clarity of the moment speaks to the possibility of love and freedom, away from the confining boundaries of the church and the questions they force a thinker to ask. Serene and hopeful, this moment encompasses the underlying and unexpected optimism in Bergman’s film. “Love is the blackest of all plagues. And if one could die of it, there would be some pleasure in love. But you almost always get over it,” Jöns reflects. “If everything is imperfect in this imperfect world, love is the most perfect in its perfect imperfection.” Such positive and indeed romantic sentiments seldom come from a pragmatist like Jöns, or a misanthrope like Bergman, but they survive through Block’s lamentations and flourish in the scenes with Jof and Mia. Cerebral though Bergman’s films may be, the director takes a realist’s stance on love, acknowledging the effort (and naiveté) it requires; yet he insists that attaining love often presents a person’s sole purpose to keep going. He grasps the potential for complication with love, and when relationships are his central theme—like in the aforementioned Smiles of a Summer Night, or Scenes from a Marriage (1973) and its sequel Saraband (2003)—Bergman often resolves that the toils are worth the plunder.

Whereas the other characters seem consumed by the times, by religious hysteria or the quest for meaning, Jof and Mia’s cheerful survival suggests that death itself is nothing to fear, because fear brings demise all the quicker. As many questions as The Seventh Seal asks, Bergman envies those un-inquisitive few unconcerned enough to not ask, because he must. In view of his entire oeuvre, Bergman searches with an infinite curiosity, probing into the meaning of it all, but he also realizes that there is no answer. Therein resides the torture felt by Block throughout the film. What remains is the importance of curiosity, of asking questions that guide through the landmines of self-discovery. Impossible though the Ultimate Truth may be, the crusade bears significance.

Proving that existential issues can be targeted in film and still reach a wide audience, Bergman’s success over the years has established him as a model voice in art-house cinema. In each piece he nourishes his own personal concerns in a precise visual and poetic language, addressing those philosophical questions that until he asked them were habitually private ruminations not meant for open discussion. But everyone asks Bergmanesque questions whether conscious of them or not, and the director’s films help further personal meditation, and thus self-understanding, in his own highly personalized, yet highly inclusive cinematic forum. Because of the sweeping nature of his spiritual and emotional brooding, his brand of weighty material garnered worldwide attention, beginning most significantly with The Seventh Seal and continuing from there. His subsequent pictures and their success continued to encapsulate the prevalent ascribed characteristics of Swedish film, so that Bergman’s name and the country’s cinematic identity are now synonymous.

Proving that existential issues can be targeted in film and still reach a wide audience, Bergman’s success over the years has established him as a model voice in art-house cinema. In each piece he nourishes his own personal concerns in a precise visual and poetic language, addressing those philosophical questions that until he asked them were habitually private ruminations not meant for open discussion. But everyone asks Bergmanesque questions whether conscious of them or not, and the director’s films help further personal meditation, and thus self-understanding, in his own highly personalized, yet highly inclusive cinematic forum. Because of the sweeping nature of his spiritual and emotional brooding, his brand of weighty material garnered worldwide attention, beginning most significantly with The Seventh Seal and continuing from there. His subsequent pictures and their success continued to encapsulate the prevalent ascribed characteristics of Swedish film, so that Bergman’s name and the country’s cinematic identity are now synonymous.

The Seventh Seal possesses some of the world’s most recognizable filmic imagery, beginning with the knight’s fateful game of chess with Death, and continuing to the eerily joyful dance in the final frames. The Medieval iconography and setting allow Bergman’s most celebrated masterpiece, fixed amid a career crowded with masterpieces, to best all others in its proven timelessness. As with all distinctive pieces of art, Bergman’s enduring themes will never lose their potency, intellect, or meaningful purpose as a result. By asking the most universal of questions in a most accessible format, Bergman exposes us to his own uncertainty and search for meaning, and forces his audience to do the same.

Bibliography:

Bergman, Ingmar. Images: My Life In Film. Foreword by Woody Allen. Arcade Publishing, 1995.

Bergman, Ingmar; Tate, Joan. The Magic Lantern: An Autobiography. University Of Chicago Press, 2007.

Cowie, Peter. Ingmar Bergman: A Critical Biography. New York: Scribner, c1982.

Singer, Irving. Ingmar Bergman, Cinematic Philosopher: Reflections on His Creativity. The MIT Press, 2007.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review