The Definitives

The Rules of the Game (1939)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

By January of 1939, Adolf Hitler’s successful Anschluss of Austria had been established for nearly a year, and Czechoslovakia’s annexation by Nazi Germany had been in place for almost as long. Poland would soon follow. Francisco Franco’s Nationalists in Spain had taken power, and France’s Prime Minister Édouard Daladier recognized the new Spanish regime, paving the way for the similar government of Marshal Philippe Pétain in France. By April 1939, the Spanish Civil War would end when Republican forces surrendered. Benito Mussolini’s Italy had already helped Franco take Barcelona, and his Fascist army was mere months away from moving into Albania. Throughout Europe, national identities were changing for the worse, and those with the power to influence decision makers paid no attention. Content in their estates and isolated by their wealth, France’s obdurate bourgeoisie remained willfully blind. In such a political and social climate, filmmaker Jean Renoir could not help but be influenced and, in an effort to deliver an acerbic commentary disguised as entertainment, he began writing The Rules of the Game (La règle du jeu). His film became one of cinema’s great treasures. Though it was also banned upon its release and, for many years, considered lost, Renoir achieved what remains a supreme appraisal of high society, as well as a deliriously accomplished and boundlessly influential motion picture.

For today’s viewer, The Rules of the Game may seem oddly lighthearted, taking the form of a farcical satire where various adulterous types pursue their infidelities, sneak around dark hallways to steal a kiss, and bewail their unrealized love affairs. At a country house getaway, wealthy couples and their servants flirt with disaster amid their respective husbands, wives, mistresses, and lovers, all the while behaving according to an absurd etiquette that defines their disciplined haute bourgeoisie culture. The story has no protagonist. The film’s subject is France’s abhorrent ruling class of the era. For Renoir, a leftist Popular Front supporter, his subject was a class of Nazi sympathizers happy to turn their heads at the world’s growing turmoil and, as Renoir described it, “dance on a volcano.” Upon its release, the film was received with passionate disapproval, banned and nearly destroyed by those who, as Renoir would later point out, experienced a degree of self-recognition. In the years since its debut, critics and film historians from André Bazin to Roger Ebert have returned to the film and written exhaustively about it (to the extent of frame-by-frame analysis). For years, cinéastes said that everything to be said about The Rules of the Game had already been written. And yet, we keep returning to the film because it requires years of absorption before one truly appreciates the sophisticated filmmaking at work. Without a doubt, there will never be enough said about this film.

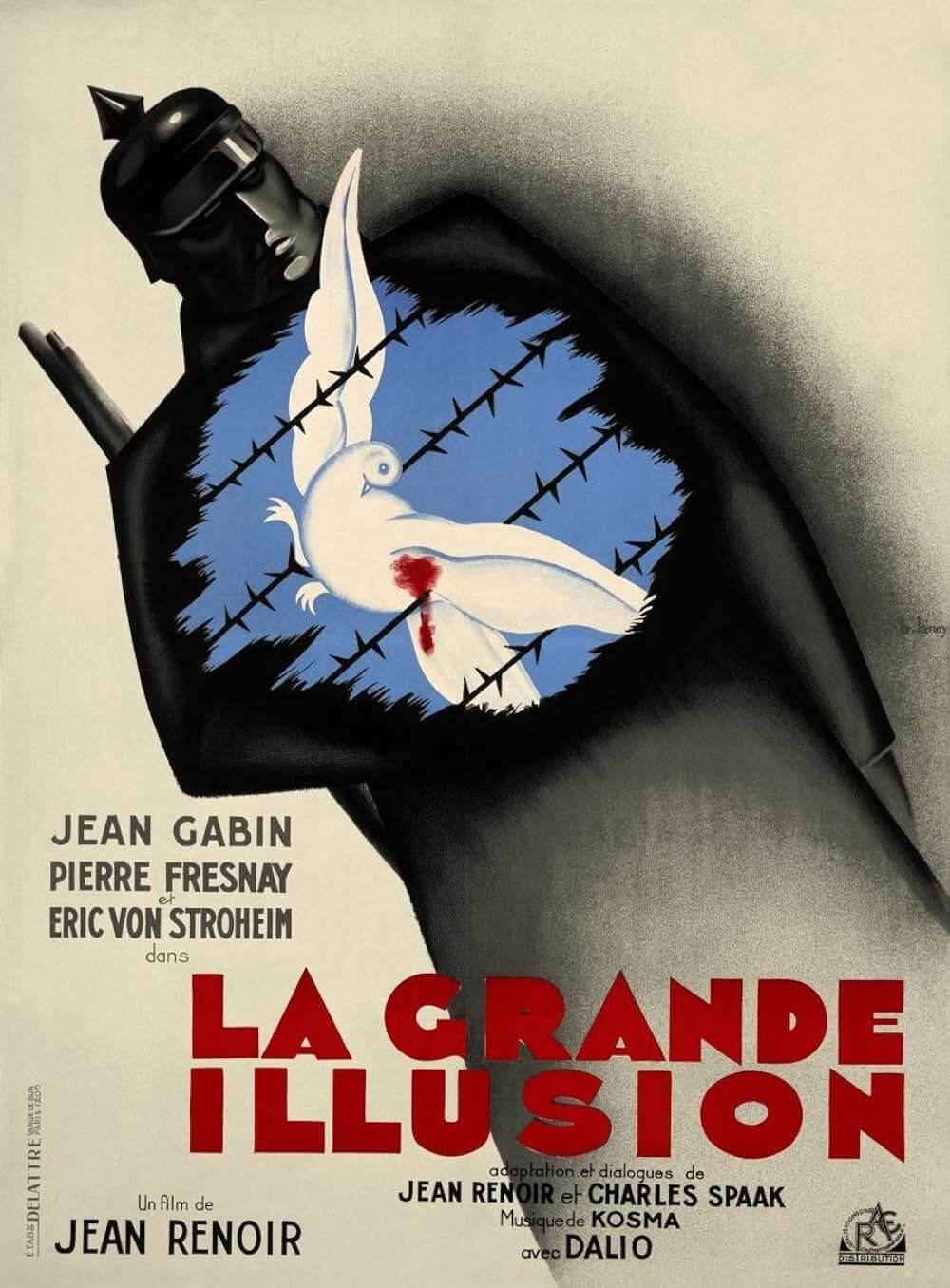

Renoir’s career as a filmmaker began in the 1920s. Having fallen in love with the films of Charles Chaplin and Erich von Stroheim, he financed early projects by selling paintings he inherited from his father, Impressionist master Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Operating on the boundaries of French cinema, Renoir resisted Hollywood archetypes that dominated world cinema and developed his own style, rich with spacious shots and deep-focus lensing that allowed his actors to move freely within the frame. Commercial successes with La chienne (1931) and Boudu Saved From Drowning (1932) brought the young director well-deserved acclaim. But in the 1930s, Renoir completed a series of films that harbored his increasingly outspoken political identity. Le crime de Monsieur Lange (1935) and La marseillaise (1938) demonstrated Renoir’s sympathies with the Popular Front movement. And though he continued to make commercial projects such as his Emile Zola adaptation La bête humaine (1938), his first landmark masterpiece Le grande illusion (1936)—a film that showed men from various nationalities and opposing sides cohabitating as POW prisoners—solidified the filmmaker’s humanist stance to the international filmgoing community. Renoir’s success enabled him to establish his own production company, Nouvelle Édition Française, with his younger brother, Claude. The idea for his next film had been planted in his head for some time, and with his reputation earning showers of praise, the seed could finally germinate.

Renoir’s perception of France’s haute bourgeoisie, or upper-middle class, comes to life in the pastoral countryside of Solone during a hunting party at a luxurious estate. Here, the filmmaker zeroes in on an entire class, representing not only familiar characterizations of any class (husbands, wives, lovers, etc.), but also doing so through a series of oppositions. In a mode later known as an upstairs-downstairs drama, he depicts the bourgeoisie in all their regimented decorum, but he also takes his camera into the servants’ quarters. Through this contrast, Renoir explores the two classes and also, quite controversially, dwells on their similarities. What could be more insulting to his targeted bourgeoisie than likening them to their underlings? But more than merely an affront to those who sympathized with or otherwise ignored the Nazi party, his association between the two classes blurred the lines between them. Just as he featured opposing classes in Boudu Saved From Drowning (wherein a bourgeois man takes in a homeless man and soon regrets his decision) or in Le grande illusion, the relationship between these disparate classes demonstrates that, beyond the meanings society assigns them, they behave in much the same way. For much of his early career, this theme percolated but never reached a level of superiority or controversy as extreme as in The Rules of the Game.

Renoir set out to make something uncharacteristic of his era, yet poetic: the same fusion of classical and romantic styles found in William Shakespeare and Pierre de Marivaux, with a “whimsical” tone not present in his earlier work, yet pointedly Renoir-esque. The style would be a combination of realism in the relationships presented, and also poeticism in how those relationships shape the narrative. For inspiration, he revisited Alfred de Musset’s 1851 comedic play Les Caprices de Marianne and began a modern adaptation set in contemporary France, borrowing character types and even the name Octave from Musset’s play. Renoir also immersed himself in French Baroque music (François Couperin, Jean-Philippe Rameau, Jean-Baptiste Lully, etc.) and imagined who would have danced to it, and then wrote his characters around those people. Beaumarchais’ Le Mariage de Figaro also supplied a source for his tone, not to mention the play’s line, “Why else does love bear wings if not to fly?” Even the film’s title references Marivaux’s popular play Le jeu de l’amour, the game of love. From a formal perspective, Renoir planned to use every corner of the space within his frame, filling the foreground, middle, and background with activity. He stages beautiful scenes in which the viewer’s attention moves from the foreground to the background, either through the placement of his characters or through a directional visual device. Note the checkered flooring that recedes into the distance along a geometric line, while keeping everything onscreen in focus and delightfully alive. His camera moves fluidly through a multifaceted narrative and class critique, but with a relevance so potent to his contemporary world that his film shocked the masses with its bold censures. The Rules of the Game would become at once a complex and provocative comic tragedy and an incomparably playful technical achievement.

During a week-long excursion to La Colinière, a chateau owned by the marquis Robert de la Chesnay (Marcel Dalio) and his wife Christine (Nora Grégor), guests arrive to hunt, drink, and be merry. Before their arrival, however, Renoir establishes their assorted desires and trysts in which the sexual tension boils. Aviator André Jurieux (Roland Toutain) has just returned from flying across the Atlantic in record time, but he wants no recognition for his achievement unless it comes from Christine, his would-be lover. But she is not there to greet him. Jurieux is consoled by Octave (Renoir), a close friend of Robert and Christine, although Octave also loves Christine. Robert is aware of Jurieux’s feelings and, to affirm his devotion to Christine, attempts to break free of his mistress, Geneviève (Mila Parély). All of the aforesaid parties and more are invited to the event at La Colinière, leaving Octave and Robert to quip that perhaps Jurieux and Geneviève will solve everyone’s problems and fall for one another. At the chateau, as a hunting tour and later a masquerade ball commence, the help have just as many sordid goings-on. The gamekeeper Schumacher (Gaston Modot), who is married to Christine’s servant Lisette (Paulette Dubost), finds a poacher, Marceau (Julien Carette), hunting rabbits on the grounds. Schumacher, on the fly, intends to deject the man, until Robert intervenes and hires Marceau as a domestic. Before long, Marceau is hunting Lisette, and Schumacher is after Marceau. Throughout the house, the sexual interplay spirals out of control as Christine begs Jurieux to take her away in secret, but then chooses Octave in his place when Jurieux insists on first informing Robert of their affair—the polite thing to do. Meanwhile, Schumacher plans to shoot Octave, whom he believes has wooed Lisette, and accidentally kills Jurieux instead, mistaking his figure for Octave’s in the gardens at night. Robert explains away the events as a regrettable accident and nothing more, and his guests retire out of courtesy, without concern.

For his cast, Renoir wanted Nora Grégor as Christine. Grégor was a legitimate Austrian princess, the wife of Prince Ernst Ruediger von Starhemberg, a nobleman and leader of an anti-Hitler peasant party. Renoir spotted her at a play recommended to him so he could assess the performance of a different actress, Michèle Alfa. Instead, Renoir saw Grégor in a box seat and was enchanted by her natural regality—an attribute that comes through in her performance—and later discovered she was an actress. When he cast her, he rewrote Christine as the daughter of an Austrian composer to explain her accent. Renoir was not so fortunate with all of his choices, though. He wanted Simone Simon, who starred in La Bête Humaine, for a role, but by this point, she had received so much acclaim that her salary demands were too high. Renoir also wanted Jean Gabin as Jurieux. Gabin had starred in three of Renoir’s last four films but was busy shooting Marcel Carné’s Le jour se lève, a fateful happenstance as Gabin’s charismatic persona could never have made Jurieux the pathetic, lovelorn man who fawns over Christine. Renoir’s elder brother Pierre was set to star as Octave, but delays in the production forced him to leave. Jean rewrote Octave for himself, changing the role into that of a sweet buffoon, a part that he could fill with his gentle face and stout figure. His financiers demanded star Michel Simon, from Boudu Saved from Drowning, take the role instead, but the actor was unavailable. If anything can be inferred from Renoir’s unrealized wish list of actors, it’s that when the filmmaker was forced to rework his ideas due to unforeseen circumstances, his natural talent often produced his finest work.

Aside from the opening scenes, production commenced at the Château de la Ferté-Saint-Aubin in Sologne—this before Renoir had finished even half the screenplay. Unlike many filmmakers, such as Renoir’s idols Chaplin and von Stroheim, Renoir approached directing with the view that preparation impeded the naturalism of on-set filmmaking. Instead, he planned with the knowledge that improvisation would dominate his production. The director believed that, in a way, actors also directed through their performances, and that it was a director’s job to motivate the actors’ performances in hopes of capturing unique moments of sincerity not previously considered in the director’s initial perception of what the film should be. Production on The Rules of the Game was slow as a result, but also because of Grégor’s stiff acting. Though she was regal in her everyday life, Renoir found her ability to project wanting and spent many hours coaxing out of her the performance he needed. He eventually rewrote the script to accommodate her abilities. As with his casting troubles, Renoir changed the script as the situation demanded, always staying true to the spirit of his original vision. More than adherence to characters or dialogue, Renoir sought a faithfulness to the spirit of an idea. “I had this subject so much inside me, so profoundly within me, that I had written only the entrances and movements, to avoid mistakes about them. The sense of the characters and the action and, above all, the symbolic side of the film was something I had thought about for a long time.”

The film premiered on July 11, 1939, at the Colisée, where it was preceded by a patriotic propaganda piece for the French Empire. A mostly right-wing audience loved the documentary and then spurned Renoir’s film. One patron lit a newspaper on fire and attempted to burn down the theater. Renoir left the theater in tears, “utterly dumbfounded” by the unanimous reaction of disapproval. He reacted by cutting its length from 113 minutes to 90, then to 85, each cut removing more scenes featuring the character Octave, the role Renoir himself played. As though he wanted to remove himself from the screen out of embarrassment, Renoir continued to reduce Octave’s presence in the film, but no matter what cuts Renoir made, the audience’s reaction was the same. By August, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs banned the film as “demoralizing” and, in a statement, announced, “We are especially anxious to avoid representations of our country, our traditions, and our race that changes its character, lie about it, and deform it through the prism of an artistic individual who is often original but not always sound.” After World War II calmed, The Rules of the Game survived only in an 85-minute version; the original cut was believed lost and went forgotten in the postwar climate. Not until 1956, when lab techs Jean Gaborit and Jacques Maréchal from the Société des Grand Films Classiques discovered original negatives and sound mixes in storage, recovered by American forces from a bombed film lab in 1942, was the film eventually reassembled into a form closer to its original cut. In 1958, the film was restored to 113 minutes, missing only one scene between Octave and Jurieux discussing the sexual proclivities of maids, which the director considered a minor loss.

The newly reconstructed version of The Rules of the Game debuted at the Venice Film Festival in 1959, the year when several Cahiers du Cinema filmmakers established the building blocks of the French New Wave: François Truffaut released Les quatre cents coups; Jean-Luc Godard had begun work on Breathless; Éric Rohmer debuted Le Signe du lion—all filmmakers who would later return to Renoir’s work, specifically The Rules of the Game, and hail it unwaveringly. However, it would not be until April 1965 that Renoir’s film was rereleased in Paris. Taking into account the film’s historical context, even after World War II, the sting of The Rules of the Game still throbbed amid the French bourgeoisie, forcing them to recall their shameless prewar behavior. Of course, they could never have known how far Hitler would go, but history remained the preeminent judge, and Renoir’s film a pitiless reminder. “The terrible thing about this world,” Renoir once said, “is that everyone has his reasons.” Yet, of his film’s characters, Renoir remarked that none of them were worth saving, not even Octave. Renoir’s character, easily the most likable of the bunch, appears in a bear suit during the costume ball and indeed behaves like a cuddly bear, sweet and comical, more so than the others, conceivably because he does not boast an evident fortune, nor does he have a lover whom he betrays. Nonetheless, Octave betrays his friend Jurieux by plotting to run away with Christine in the finale, even if he finally tells Jurieux to take her instead. Renoir’s judgment of his characters is scathing, despite the veneer of a farcical romance.

As such, Renoir’s judgment of both the past and present bourgeois culture was just as brutal. This is never truer than in the film’s famous hunting scene, where the guests venture out onto La Colinière’s vast fields, weapons loaded, sportsmanship of no concern as Schumacher’s crew rustles up prey for the aristocrats. What follows is a barrage of gunfire as the hunt commences. One after another, birds fall from the sky, and rabbits are struck dead. Renoir closes the sequence by lingering on a particular rabbit whose agony seems to remain onscreen for much longer than any audience can handle. The sequence foreshadows the “unfortunate” death at the end of the film. Hit with the shotgun blast, Jurieux falls to the ground, not unlike the rabbit from the hunt, although we have watched Jurieux’s agony throughout the film. Safe in their hunting blind of the chateau, the bourgeoisie do not weep for their friend. But the party, for now, is over. Jurieux dies because he failed to play The Game with as much skill as his fellow party guests. In other words, he fell in passionate love, and his fatal mistake was trying to express it. The Rules state that a married person can take a lover, but out of respect for one’s spouse, the other party must not be flaunted, taken seriously, or displayed in such a way that would reflect poorly on the spouse. After Jurieux publicly announces his love for Christine in the opening scene, anyone could have guessed that Jurieux would be punished for his crime.

To disrupt the illusion of good-mannered composure, the safe and secreted calmness of infidelity running rampant through this society threatens The Game itself. Someone who feels genuine love, such as Jurieux, does not belong in The Game, and thus Jurieux aligns more with the common man, trampled by the upper class, than a member of that class himself. For Renoir, to aspire to become one of the bourgeoisie is every bit as criminal as being one of them. And like Jurieux, Schumacher refuses to play along and chases Marceau without reservation. During the fracas, Robert orders his servant to “Put an end to this farce!” The servant replies, “Which one, sir?” But Schumacher and Marceau, being the underlings they are, are not expected to understand The Game because of their class. Perhaps this is why Renoir made Robert, a Jewish man, the film’s most skilled player. At once, Robert’s noble status affords him considerable knowledge of The Game and how it must be played, yet, being Jewish in prewar France, he has lived just on the margins of his class, and thus he can sympathize with Marceau. For right-wing French audiences and Nazi sympathizers, the notion of a Jewish man playing The Game better than anyone else became the film’s final insult.

Watching The Rules of the Game today, Renoir’s subversive intentions may almost be missed. Of the film, Bazin wrote that the viewer must play The Game to grasp the sophistication behind its message; an audience must be “in” to feel part of the proceedings and the film’s purpose. Though a dying rabbit is anything but subtle, Renoir does not over-emphasize his point; rather, he allows the proceedings to play out in frivolous romances. In a 1958 interview with Bazin in France Obervateur, Renoir remarked on his approach: “In the cinema at present the camera has become sort of a god. You have a camera, fixed on its tripod or crane, which is just like a heathen altar; around it are the high priests—the director, cameraman, assistants—who bring victims before the camera, like burnt offerings, then cast them into the flames. And the camera is there, immobile—or almost so—and when it does move, it follows patterns ordained by the high priests, not by the victims. Now… the camera finally has only one right—that of recording what happens. That’s all. I don’t want the movements of the actors to be determined by the camera, but the movements of the camera to be determined by the actor […] It is the cameraman’s duty to make it possible for us to see the spectacle, rather than the duty of the spectacle to take place for the benefit of the camera.”

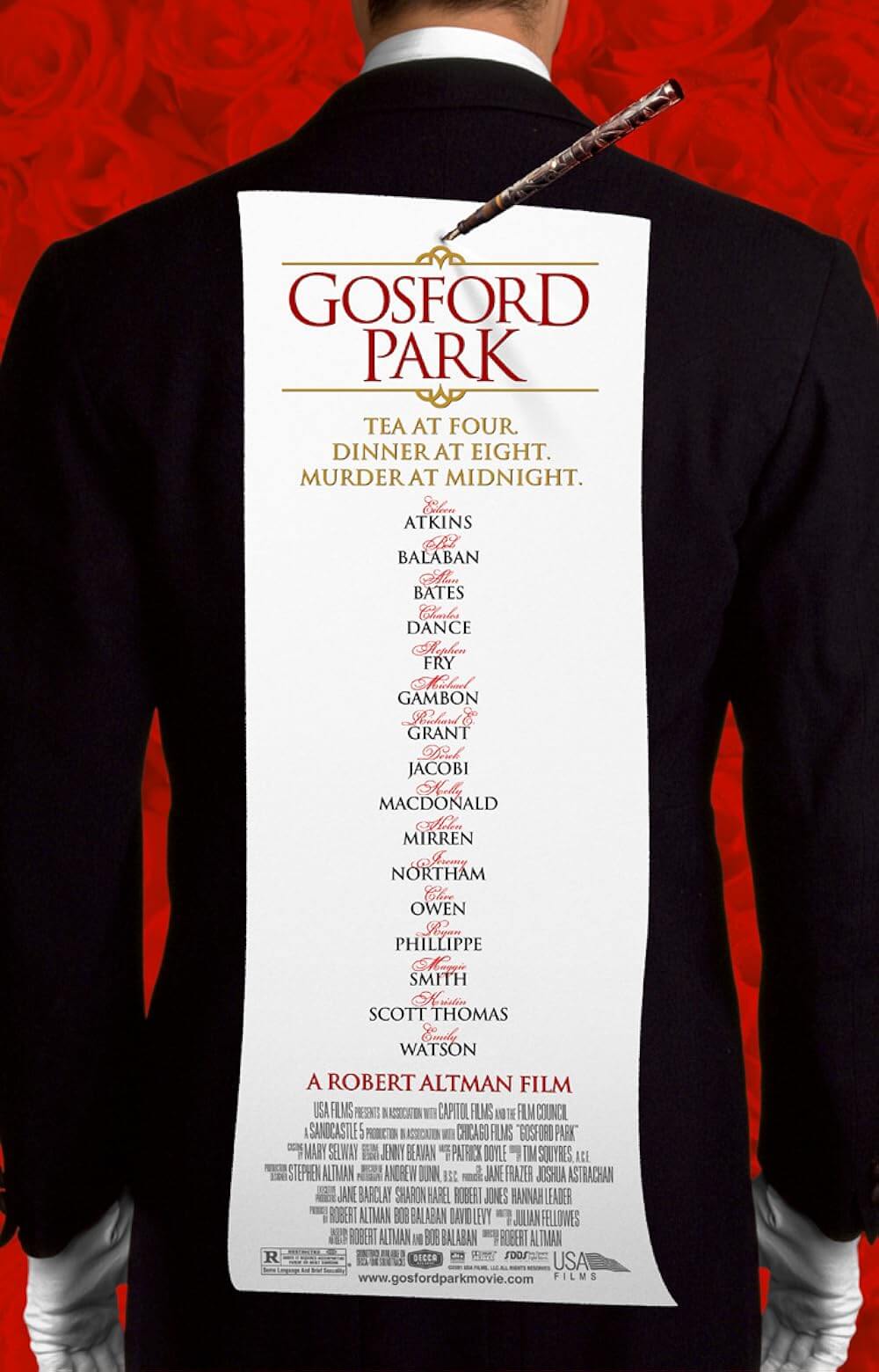

Today, Renoir’s improvisational approach is almost impossible to grasp when considering the virtuosity on display in the finished film. The camera’s movements flow with a freeness and precision that other filmmakers labor to achieve. He retains deep focus throughout complex sequence shots, following the hustle-and-bustle with incredible clarity. Often, Renoir’s personal style has been called difficult to define, not only because his films cover a range of topics, but perhaps because his devotion to his actors determines how he films a scene. Consider Le grande illusion, which has fewer characters confined in various POW camps; the film’s camera moves much less as a result. Renoir seeks to create a vast stage, like a theatrical play, where truth is apparent and not obstructed by cinematic trickery. He reveals an entire world full of detail without fragmenting it through editing. The converse approach would be montage, which Renoir avoids as a propelling device in his films. If not for cutting and rare close-ups, watching The Rules of the Game might be more like attending the theater. Moreover, his approach has been hugely influential. Robert Altman once said, “I learned the rules of the game from The Rules of the Game.” This avowal becomes most apparent in Altman’s work, often based on the notion of tracking several characters in an involved mosaic, such as Nashville (1975) or Short Cuts (1993), or his exercises in deep focus, such as The Player (1992). Altman’s influence is most apparent in Gosford Park (2001), almost a modern remake of Renoir’s film, but more somber and set on the English countryside.

In more sweeping testimonials, filmmakers such as Truffaut and Orson Welles have called Renoir the greatest director in the history of cinema. Welles wrote as much in Renoir’s obituary for the Los Angeles Times in February 1979. Of all Renoir’s films, The Rules of the Game is undoubtedly his most complex piece of filmmaking, wherein he tests not only his artistic and narrative limits but also his audience, who must dissect the multiple levels occupying every scene to fully appreciate its genius. A filmmaker of unparalleled instinct and insight, Jean Renoir fills The Rules of the Game with a network of emotions, making this film, and all of his films, rewarding, if not essential to revisit for their wealth of substance. But this is not merely a time capsule of a particular era in French history. Though conceived amid the frightening times leading up to World War II, his social satire remains relevant today, particularly in cultures where class divisions have reached contemptible levels. In its time, cinema had never been more powerful or daring, and doubtless, no film will ever generate the same degree of fervent reactions. Contrary to what Bazin has argued—though framing the film historically brings a greater appreciation for the political and class subtext—Renoir’s unrelenting cynicism remains evident as he pursues the vain activities of a decaying society, even without an informed viewing. Above all, Renoir makes the interwoven romances, class commentary, and technical bravado in his film look effortless despite their complexity, leaving it a masterwork not only of its era but for all time.

Bibliography:

Bazin, André, and François Truffaut. Jean Renoir. Simon and Schuster, 1973.

Bergan, Ronald. Jean Renoir: Projections of Paradise. The Overlook Press, 1992.

Renoir, Jean. My Life and My Films. Da Capo Press, 1991.

Sesonske, Alexandre. Jean Renoir: The French Films, 1924-1939. Harvard University Press, 1980.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review