The Definitives

The Road Warrior

Essay by Brian Eggert |

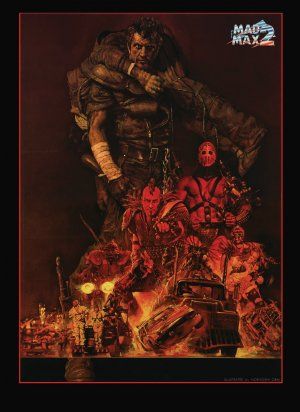

A wall of vehicles manned by post-apocalyptic marauders has lined up outside of the compound, headed by their hockey-masked leader, The Humungus. All at once, a semi-truck pulling a tanker of gas emerges at top speeds from inside, racing to escape the marauders. Overhead, a gyrocopter drops flaming Molotovs onto the enemy wall and they scatter, making a hole. Behind the wheel of the semi, Mad Max crashes through the line of vehicles as his cabin passenger, the grunting Feral Kid, ducks for cover. The chase has begun. The Humungus races after Max and the gas inside the tanker in his super-charged dragster, his crew fronted by the mohawked Wez. Atop the tanker, Max’s allies have mounted a trivial defense against the dozen or more cars that surround them on the open road. Marauders begin to board the semi, shooting arrows, guns, and grapples to strip away the defenses. Max kills off a few, but not enough, and in the chaos he nearly loses control and turns the truck around. No one is left except Max, the Feral Kid, and a double-barrel shotgun—the last shell for which now rattles on the semi’s hood. Crawling out there carefully, the Feral Kid grabs the last shell, and as he does, Wez abruptly seizes him, screaming like a madman. As Max wrestles to pull the boy back into the truck’s cabin, he sees in the distance a car driven by The Humungus, heading toward them on a collision course at nitrous oxide speeds. Max forgets the shell, heaves the boy to safety, and smashes into The Humungus head-on, obliterating both Wez and The Humungus, while toppling the semi onto its side. Thus ends one of the most spectacular action sequences in cinema history.

A post-apocalyptic surge of adrenaline by any other name would be just as brutal, energized, and entertaining. Called Mad Max 2 in Australia and The Road Warrior stateside, George Miller’s follow-up to his 1979 endeavor remains the defining Mad Max film. For the purposes of this appreciation and its concentration on the film’s theme of myth-making, let’s avoid the sequel-ized title and use the far more legendary-sounding label: The Road Warrior. Indeed, this first sequel falls into mythological territory and launches its titular character into the realm of legend. In that respect, the film is less about developed characters who learn important lessons and suffer tragedy than its predecessor, and more about embracing cinematic traditions established around heroic archetypes. Specifically, Miller, along with his co-writers Terry Hayes and Brian Hannant, craft their story in the framework of Akira Kurosawa samurai pictures (namely Yojimbo, 1960), which in turn derive from the American Western. For example, Miller borrows liberally from George Stevens’ classic Western from 1953, Shane.With those ideas at the forefront of Miller’s imagination, along with the visionary impetus to realize incredibly ambitious vehicular chases and crashes, the director released an unforgettable post-apocalyptic chase film unto the world in 1981, and cinema still hasn’t recovered.

After the international success of Mad Max, Miller and his producer, the late Byron Kennedy, sought to deepen their protagonist’s mythology and redefine him. Mad Max had received some condemnation from critics for its embrace of vigilantism, as Max’s cavalcade of violence against those who killed his wife and child at the climax of the original was a remorseless, at times distasteful display of inexorable bloodlust. What The Road Warrior does so well is transform Max from a misunderstood, anti-heroic badass (like Snake Plissken, The Man With No Name, Nada, John McClane, and Dirty Harry) into a hero redeemed—a complex champion who, by the end, earns his place among the mythic samurai of ancient Japan and gunslingers of the Wild West. Throughout the course of the film, Max moves away from being a troubled, trustless survivor; instead, he helps those in need and regains his humanity. Miller once said, “Mad Max was, in fact, another story about a lone outlaw who wandered through a dark wasteland—similar stories had been told over and over again, across all space and time, with the hero being a Japanese samurai.” Indeed, rather than employ another amoral, revenge-bent anti-hero, Max becomes something more akin to Toshiro Mifune’s lone samurai in Yojimbo, who finds himself caught between two rivaling gangs, and in spite of his outward selfishness, ultimately resolves to take the moral side.

After the international success of Mad Max, Miller and his producer, the late Byron Kennedy, sought to deepen their protagonist’s mythology and redefine him. Mad Max had received some condemnation from critics for its embrace of vigilantism, as Max’s cavalcade of violence against those who killed his wife and child at the climax of the original was a remorseless, at times distasteful display of inexorable bloodlust. What The Road Warrior does so well is transform Max from a misunderstood, anti-heroic badass (like Snake Plissken, The Man With No Name, Nada, John McClane, and Dirty Harry) into a hero redeemed—a complex champion who, by the end, earns his place among the mythic samurai of ancient Japan and gunslingers of the Wild West. Throughout the course of the film, Max moves away from being a troubled, trustless survivor; instead, he helps those in need and regains his humanity. Miller once said, “Mad Max was, in fact, another story about a lone outlaw who wandered through a dark wasteland—similar stories had been told over and over again, across all space and time, with the hero being a Japanese samurai.” Indeed, rather than employ another amoral, revenge-bent anti-hero, Max becomes something more akin to Toshiro Mifune’s lone samurai in Yojimbo, who finds himself caught between two rivaling gangs, and in spite of his outward selfishness, ultimately resolves to take the moral side.

By the end of The Road Warrior, Max no longer resembles the ruthless vigilante from Mad Max; he now echoes someone more analogous to Alan Ladd in Shane. Whereas the gunslinger Shane helped a family of homesteaders defend themselves from a ruthless cattle baron, Max helps defend a civilized community escape the clutches of a marauder gang. But The Road Warrior functions as myth long before Max has a chance to save the day; in fact, the film functions as mythology within the first frames. A voice, a storyteller narrates a great tale of his world: “My life fades. The vision dims,” says the storyteller. “All that remains are memories. I remember a time of chaos. Ruined dreams. This wasted land. But most of all, I remember The Road Warrior. The man we called ‘Max’. To understand who he was, you have to go back to another time.” In part, the opening narration serves as an excuse to recap the events from Mad Max for anyone who may have missed it. Also, the storyteller explains how the world became an incinerated post-apocalypse after World War III. From this, a hero emerged. As the storyteller recounts, “In the roar of an engine, he lost everything and became a shell of a man. A burnt out, desolate man. A man haunted by the demons of his past. A man who wandered out into the Wasteland. And it was here, in this blighted place, that he learned to live again…”

The plot itself is pure and simple. Scavenging in his black supercharged V-8 Pursuit Special, Max roams the desert Wasteland alongside his sole companion, a smart Australian Cattle Dog. Max searches for petrol while pursued by a red-mohawked ravager, named Wez (Vernon Wells), who, clad in leather, carts his mute boy-toy behind him on a chain. Max escapes and soon finds an autogyro pilot (Bruce Spence) who claims to know the location of a nearby refinery. He takes the pilot prisoner and, watching from a safe distance, observes as the walled, carefully guarded facility defends itself from a terrifying crew of bikers and drivers led by The Humungus (Olympic bodybuilder Kjell Nilsson). After the gang disperses, Max approaches the compound and negotiates with their leader, Pappagallo (Michael Preston), to help them escape their compound with their petrol in tow. He offers to sneak out, steal a semi-truck he saw earlier, and then return with it, all in exchange for some fuel. After he completes the bargain, Max leaves as promised, but on his own, he loses his dog and nearly dies when The Humungus’ gang attacks. Desperate and now alert to how The Humungus’ gang is just waiting for the community to run for it, Max offers to drive the semi-truck and haul the tanker during the escape. When he does, the Feral Kid (Emil Minty), who has taken a liking to Max, joins him in the truck, and together they draw the gang’s attention in a breakneck chase that leaves The Humungus’ gang dead, and the truck and its tanker overturned. But inside, there is no petrol, just sand. During the chase, the rest of the group has quietly escaped with barrels of fuel packed into smaller vehicles, thankful that The Road Warrior, who continues to wander through the Wasteland, made a sacrifice to protect them.

The plot itself is pure and simple. Scavenging in his black supercharged V-8 Pursuit Special, Max roams the desert Wasteland alongside his sole companion, a smart Australian Cattle Dog. Max searches for petrol while pursued by a red-mohawked ravager, named Wez (Vernon Wells), who, clad in leather, carts his mute boy-toy behind him on a chain. Max escapes and soon finds an autogyro pilot (Bruce Spence) who claims to know the location of a nearby refinery. He takes the pilot prisoner and, watching from a safe distance, observes as the walled, carefully guarded facility defends itself from a terrifying crew of bikers and drivers led by The Humungus (Olympic bodybuilder Kjell Nilsson). After the gang disperses, Max approaches the compound and negotiates with their leader, Pappagallo (Michael Preston), to help them escape their compound with their petrol in tow. He offers to sneak out, steal a semi-truck he saw earlier, and then return with it, all in exchange for some fuel. After he completes the bargain, Max leaves as promised, but on his own, he loses his dog and nearly dies when The Humungus’ gang attacks. Desperate and now alert to how The Humungus’ gang is just waiting for the community to run for it, Max offers to drive the semi-truck and haul the tanker during the escape. When he does, the Feral Kid (Emil Minty), who has taken a liking to Max, joins him in the truck, and together they draw the gang’s attention in a breakneck chase that leaves The Humungus’ gang dead, and the truck and its tanker overturned. But inside, there is no petrol, just sand. During the chase, the rest of the group has quietly escaped with barrels of fuel packed into smaller vehicles, thankful that The Road Warrior, who continues to wander through the Wasteland, made a sacrifice to protect them.

The Road Warrior went into production quickly after the release of Mad Max, since that film was such a prominent international hit. The original was purchased for U.S. distribution by American International Pictures (AIP), which was later sold to Filmways, Inc. in 1979, and then renamed Filmways Pictures. Their muddled distribution, which included dubbing the Australian dialogue with American accents in the U.S. release, paid off by earning nearly $100 million at the international box-office. Hollywood wasted no time in reaching out to Miller for his next directorial effort, but after turning down several large offers, he resolved to work on a sequel with Terry Hayes, who wrote the novelization of Mad Max, and Brian Hannant, director of the 1972 drama Flashpoint. For The Road Warrior, Warner Bros. handled worldwide distribution. Miller and Kennedy had been given a considerably larger budget than the first ($4 million, compared to Mad Max‘s paltry $400,000). With it, they explored vehicular mayhem at its finest, employing some 80 vehicles and shooting hundreds of stunts in the Outback near the mining town of Broken Hill, in New South Wales. They achieved what Andrew Sarris, in his review for The Village Voice, called “an honest-to-goodness movie-movie of such breathtaking velocity that it would spin hopelessly out of control if it did not have a charismatic hero at its core.”

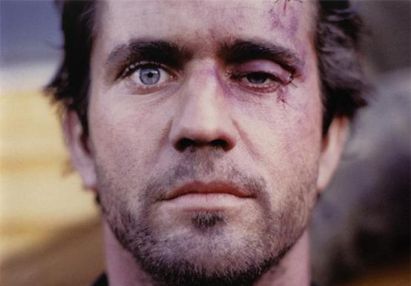

While the emotional center in the original involved a tragedy and its resultant outburst of revenge, the second film follows Max long after he has closed himself off from the world. Andrew Sarris wrote that The Road Warrior was “more satisfying as genre entertainment than Mad Max because its heroics are driven less by vengeance than a vision.” But The Road Warrior has a reticent sense of emotion, defined by Gibson’s reserved performance. When the film opens, Max can hardly bring himself to show affection for his loyal dog after he lost his wife and child; he treats the animal as a worthy companion to be sure, but from a distance—just enough so loneliness doesn’t overcome him. Surely, not even women of the compound interest Max. In his review for The New York Times, Vincent Canby remarked,“Max is apparently too busy remembering the unthinkable to have any time for romantic or even sexual thoughts.” Max’s sexuality seems to have been squashed in the moment his wife died. Instead, he has only fond memories of his young boy. When he first arrives within the walls of the compound, Max treats the Feral Kid with a distant affection, similar to how he treats his dog. He tosses the boy a wind-up music box he found earlier, if only to see him smile in his grunting way. Despite spending years on the road alone, Max yearns to regain his humanity, not unlike the gunslinger Shane in George Stevens’ film. The Feral Kid has a clear counterpart in Shane‘s young boyJoey, played by Brandon deWilde; Joey looks up to the rugged gunslinger as a hero. And like Shane, Max keeps his reasons and his undoubtedly sordid, shameful past a mystery. The viewer must watch Gibson’s subtle facial cues to appreciate the full extent of Max’s tragic station.

While the emotional center in the original involved a tragedy and its resultant outburst of revenge, the second film follows Max long after he has closed himself off from the world. Andrew Sarris wrote that The Road Warrior was “more satisfying as genre entertainment than Mad Max because its heroics are driven less by vengeance than a vision.” But The Road Warrior has a reticent sense of emotion, defined by Gibson’s reserved performance. When the film opens, Max can hardly bring himself to show affection for his loyal dog after he lost his wife and child; he treats the animal as a worthy companion to be sure, but from a distance—just enough so loneliness doesn’t overcome him. Surely, not even women of the compound interest Max. In his review for The New York Times, Vincent Canby remarked,“Max is apparently too busy remembering the unthinkable to have any time for romantic or even sexual thoughts.” Max’s sexuality seems to have been squashed in the moment his wife died. Instead, he has only fond memories of his young boy. When he first arrives within the walls of the compound, Max treats the Feral Kid with a distant affection, similar to how he treats his dog. He tosses the boy a wind-up music box he found earlier, if only to see him smile in his grunting way. Despite spending years on the road alone, Max yearns to regain his humanity, not unlike the gunslinger Shane in George Stevens’ film. The Feral Kid has a clear counterpart in Shane‘s young boyJoey, played by Brandon deWilde; Joey looks up to the rugged gunslinger as a hero. And like Shane, Max keeps his reasons and his undoubtedly sordid, shameful past a mystery. The viewer must watch Gibson’s subtle facial cues to appreciate the full extent of Max’s tragic station.

Miller creates a scarred world in The Road Warrior, one shaped by emotional trauma, and much more complex than the rather simple, linear plotting might otherwise suggest. Canby was wrong when he wrote, “It has no pretensions to do anything except entertain in the primitive, occasionally jolting fashion of the first nickelodeon movies, whose audiences flinched as streetcars lumbered silently toward the camera.” If this were true, Miller could have painted his characters in oppositional black and white. But even The Humungus shows a hint of compassion when he speaks the most sensible words ever uttered by a man in leather straps whose veins pulsate under his hockey mask: “I understand your pain. We’ve all lost someone we love… There has been too much violence. Too much pain. But I have an honorable compromise. Just walk away. Give me your pump, the oil, the gasoline, and the whole compound, and I’ll spare your lives.” In another scene, the gyrocopter’s pilot watches from afar as gang members rape and kill a woman. He must have seen countless acts of violence and death by this point; and yet, he cannot help but look away disgusted, shaken. Miller creates a Wasteland in which the wounds of loss from the former civilization have not completely callused. Had everyone moved on and accepted the new, compassionless way of scavenged living, the world would be far too easy on the viewer. But there’s more in The Road Warrior than such polarization. Not Max, not the gyrocopter pilot, and perhaps not even The Humungus have completely shed the former world. Only Wez seems to have fully embraced the monstrosity of the post-apocalypse.

Though The Road Warrior would not become the near $100 million oddity and phenomenon that its predecessor had become, critics received the film far better, and it made a much deeper impact on popular culture. Its plot mechanics and the story momentum were far more consumable in this very forward-moving package; however, because the film was less rooted in drawing the audience through exploitation than Mad Max, it attracted fewer crowds. Still, the late Richard Corliss wrote in Time, “Miller keeps the eye alert, the mind agitated, the Saturday matinee spirit alive evoking emotion through technique.” The director used a combination of feral editing, elaborate automobile choreography, head-on collisions, pyrotechnics, and high-speed chases to give the film an illusory non-stop feel. He mounted cameras on vehicles and raced them on abandoned highways at incredible speeds. In a way, the film seems like a never-ending chase sequence apart from the grandly narrated prologue and epilogue. Much of what Miller achieves is illusory in this sense; he has such control over the craft of filmmaking that he creates the impression of both a simpler plot and more violence than actually appears onscreen. Watching closely, an observant viewer will see little viscera. As Miller admitted, “I had censorship problems… And it was extremely difficult to make any cuts because, as you’d see if you looked at them frame by frame or sequence by sequence, there’s not much violence on the screen. They appear to be more violent than they are. That was deliberate.”

Though The Road Warrior would not become the near $100 million oddity and phenomenon that its predecessor had become, critics received the film far better, and it made a much deeper impact on popular culture. Its plot mechanics and the story momentum were far more consumable in this very forward-moving package; however, because the film was less rooted in drawing the audience through exploitation than Mad Max, it attracted fewer crowds. Still, the late Richard Corliss wrote in Time, “Miller keeps the eye alert, the mind agitated, the Saturday matinee spirit alive evoking emotion through technique.” The director used a combination of feral editing, elaborate automobile choreography, head-on collisions, pyrotechnics, and high-speed chases to give the film an illusory non-stop feel. He mounted cameras on vehicles and raced them on abandoned highways at incredible speeds. In a way, the film seems like a never-ending chase sequence apart from the grandly narrated prologue and epilogue. Much of what Miller achieves is illusory in this sense; he has such control over the craft of filmmaking that he creates the impression of both a simpler plot and more violence than actually appears onscreen. Watching closely, an observant viewer will see little viscera. As Miller admitted, “I had censorship problems… And it was extremely difficult to make any cuts because, as you’d see if you looked at them frame by frame or sequence by sequence, there’s not much violence on the screen. They appear to be more violent than they are. That was deliberate.”

Stunt insurance, risk assessors, and the ease of CGI have all but eliminated the authentic car chase in today’s cinema. But in 1980, Miller was shooting near the end of an era, yet still enough in the wilds to be dangerous and daring. He did not rely on computer-generated imagery or animations to realize his surprisingly multilayered world, nor its fast-paced chase sequences. In fact, Miller even avoided miniatures, a popular solution to large car wrecks at the time. Using real cars and in-camera effects, Miller achieved life-or-death stunts. One rather unbelievable story from the set involves a stunt driver who, in preparation for the climactic scene where the semi-truck flips and crashes, was told not to eat for twelve hours prior to filming—just in case he should be injured during the shoot and needed to go into surgery. Fortunately, he emerged from the crash unharmed. The intense energy of the semi-inflected chases in The Road Warrior would later inspire James Cameron on The Terminator (1984) and its first sequel, Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991). Several entries in the Fast and Furious series have borrowed from The Road Warrior as well. Elsewhere, Miller’s scenario inspired films like Waterworld (1995) and videogames such as the Borderlands series. And, for better or worse, it further established Mel Gibson as an international star and action hero, years before names like Schwarzenegger, Stallone, and Willis founded the pantheon of movie action heroes.

Of course, Miller’s trilogy continued after The Road Warrior with a Hollywood-ized version of the post-apocalypse in Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985), in which Max fully redeems himself and recovers his human compassion. By the third film’s end, the place of each entry within the original trilogy becomes absolutely clear, as does the perfect equilibrium achieved by The Road Warrior between its two diametric entries. The first, rather harsh film embraced exploitation and unrelenting violence as a means to crush Max’s soul, and achieves its bleak outlook with an expert rage. The final film would soften Max into a PG-13 rated, borderline family-friendly version of the character, who redeems himself and recaptures his humanity by saving a group of children. If the Mad Max trilogy as a whole is about anything beyond Miller’s kinetic energy and expert automobile stuntwork, it is about the protagonist losing his humanity and then regaining it again, and in that process establishing himself as a mythic hero. This ambition, while accomplished over the course of three films, is quite efficiently achieved within The Road Warrior alone, which epitomizes the entire trilogy’s journey and mythology in a single, brilliant stroke. In a way, the film almost renders what came before and what followed to be irrelevant. Miller, the storyteller, recites the entire legend of Mad Max within The Road Warrior, and it’s a vision that echoes far beyond the reach of a single film.

Of course, Miller’s trilogy continued after The Road Warrior with a Hollywood-ized version of the post-apocalypse in Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985), in which Max fully redeems himself and recovers his human compassion. By the third film’s end, the place of each entry within the original trilogy becomes absolutely clear, as does the perfect equilibrium achieved by The Road Warrior between its two diametric entries. The first, rather harsh film embraced exploitation and unrelenting violence as a means to crush Max’s soul, and achieves its bleak outlook with an expert rage. The final film would soften Max into a PG-13 rated, borderline family-friendly version of the character, who redeems himself and recaptures his humanity by saving a group of children. If the Mad Max trilogy as a whole is about anything beyond Miller’s kinetic energy and expert automobile stuntwork, it is about the protagonist losing his humanity and then regaining it again, and in that process establishing himself as a mythic hero. This ambition, while accomplished over the course of three films, is quite efficiently achieved within The Road Warrior alone, which epitomizes the entire trilogy’s journey and mythology in a single, brilliant stroke. In a way, the film almost renders what came before and what followed to be irrelevant. Miller, the storyteller, recites the entire legend of Mad Max within The Road Warrior, and it’s a vision that echoes far beyond the reach of a single film.

Bibliography:

Corliss, Richard “Apocalypse… Pow!”. Time. May 10, 1982.

Perry, Danny. Cult Movies 3: 50 More of the Classics, the Sleepers, the Weird and the Wonderful. Fireside; 1st edition, 1988.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review