The Definitives

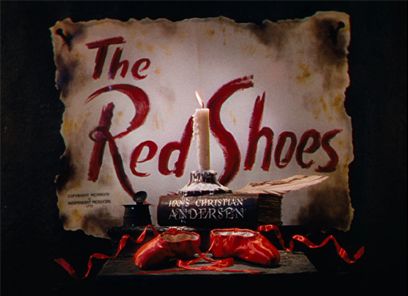

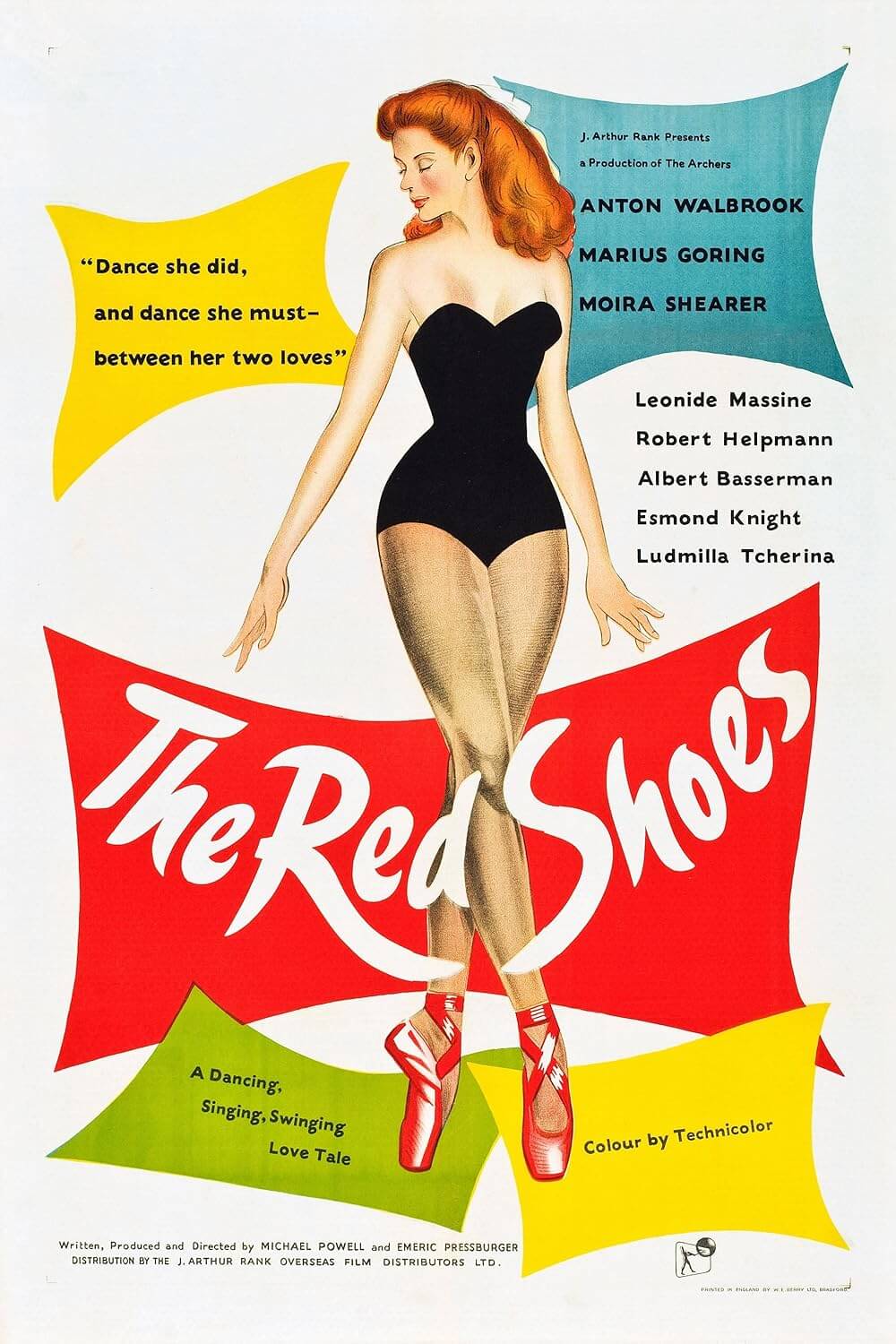

The Red Shoes (1948)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s The Red Shoes spearheaded the notion that cinema and dance, through mediums of expression with varied modus operandi, could coalesce in a singular form. Through a harmony of visual and aural elements, the British filmmaking partners known as The Archers embrace ballet as an unlikely component in their cinema; and through their conception, one of the most beautiful and meaningful of all films, they affirm that all art exists on analogous terms. From The Red Shoes springs the spirit of art in both its narrative and technical composition, signifying Powell and Pressburger’s desire to coordinate all cinematic devices to express creative unity in front of, and therefore behind, the camera. Powell, the director of Pressburger’s scripts, once declared that miracles occur in his films. This was never truer than with The Red Shoes, a haunting story about how art consumes the artist from the inside out. Based on the fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen, the 1948 film was photographed in gorgeous three-strip Technicolor by Powell and Pressburger’s frequent cinematographer Jack Cardiff. It contains color of inconceivable range, with reds so vibrant they have not been rendered since the work of Flemish painter Jan Van Eyck. The inclusion of bravura ballet sequences into its narrative would influence later extended dance numbers in Hollywood, namely those by Gene Kelly and Vincente Minnelli. But the enduring quality of the picture goes beyond its individual elements. The miracle Powell refers to resides in the seemingly supernatural way it all comes together to form pure cinema.

The Archers sought an ideal that aligned with the earliest aspirations for cinema: that the medium would transcend all customary art forms by combining them into a concentrated whole, which, if successful, would imply that all art is relative. Early filmmakers such as Sergei Eisenstein, Abel Gance, and Norman King sought to make a “great symphony of sound and vision” in their cinema, merging cinematic artifice with a story to bring about consistency between the medium’s lighting, sound, color, and narrative—all individual cinematic modules, and all individual artforms on their own. Powell and Pressburger wanted each film to represent an “organic whole” where these technical modules operate toward the same unified totality: art constructing art. Before launching the The Archers production company under J. Arthur Rank, Powell and Pressburger showed individual promise; but not until they joined creative forces would their art become an entirely unique voice in British or any other cinema. The Red Shoes was a project that could not exist without their partnership and the inspired drive for excellence that came from their collaboration. Pressburger had been commissioned to write an adaptation of Andersen’s tale in 1937 for Alexander Korda, the producer who brought director Powell and screenwriter Pressburger together. The proposed project would star Korda’s fiancée Merle Oberon; despite her inability to dance, Korda insisted a double could be used to stand-in during the dance sequences. Nevertheless, the project was shelved for eight years, until Powell and Pressburger had become established as The Archers and chose to revisit Pressburger’s script.

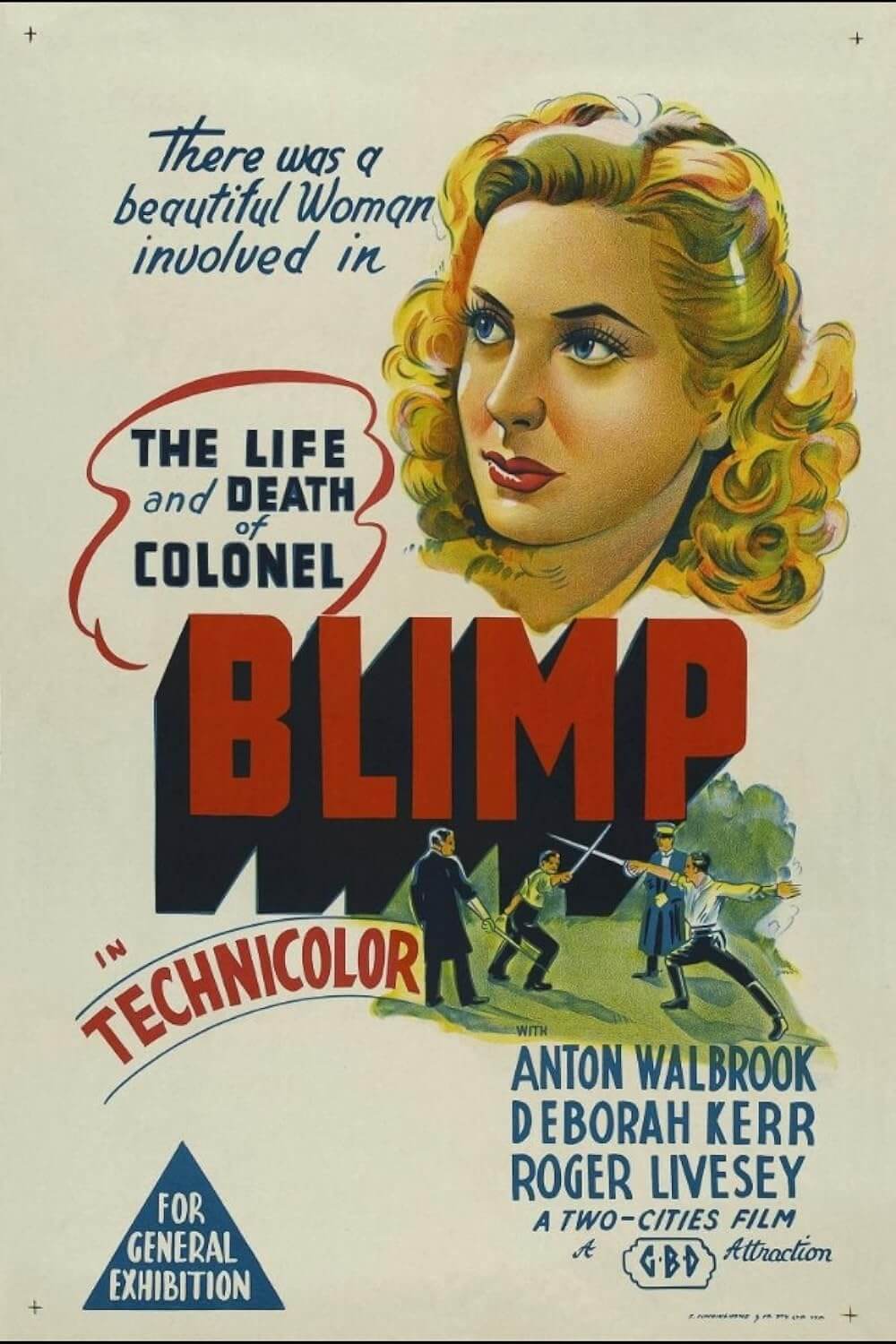

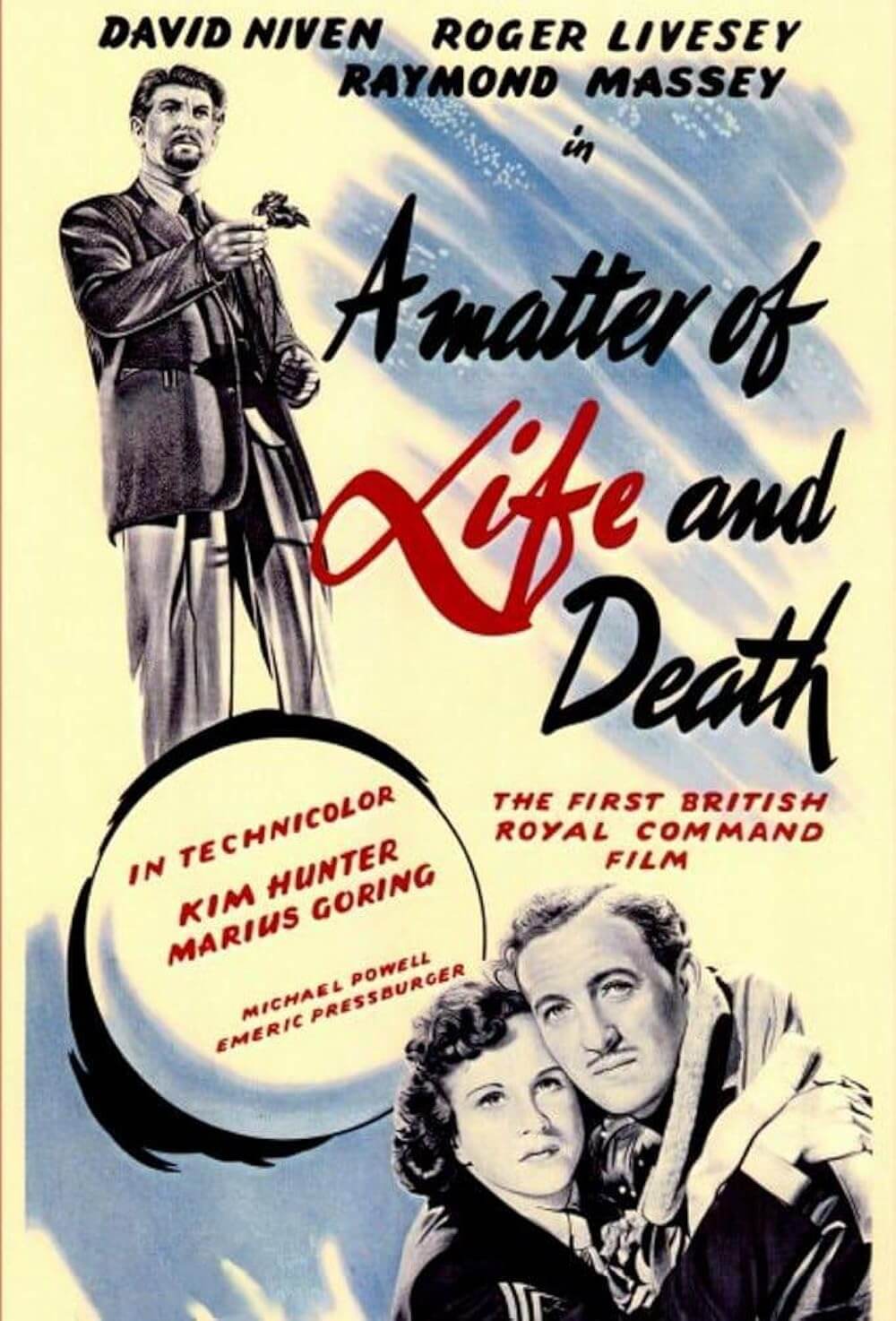

As The Archers, the filmmaking duo took aim at controversial subject matter, but in a way that circumvented negative responses to their pictures. It was their intention to push the limits of representation without toppling over the line or becoming outright provocateurs. Their 1941 picture 49th Parallel, while taking place entirely within Canadian borders, presented the threat of Nazis crossing over into the United States in an attempt to involve American viewers in World War II. At the prime of World War II in 1943, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp humanized David Low’s scathing caricature of the stuffy British political and military establishment whereas, at the same time, they acknowledged how obsolete the ways of the current, archaic administration had become. A Matter of Life and Death in 1946 put forward that the utopia of Heaven was just as constrained by officialdom as bureaucracies on Earth. In 1947 they made Black Narcissus, a film about nuns resisting sexual and spiritual temptations in an Orientalized Himalayan monastery, a conflict which paralleled Britain’s withdrawal from India. Such examples are persistent throughout Powell and Pressburger’s time together, each one confronting the audience with otherwise unspoken but characteristically British concerns.

As The Archers, the filmmaking duo took aim at controversial subject matter, but in a way that circumvented negative responses to their pictures. It was their intention to push the limits of representation without toppling over the line or becoming outright provocateurs. Their 1941 picture 49th Parallel, while taking place entirely within Canadian borders, presented the threat of Nazis crossing over into the United States in an attempt to involve American viewers in World War II. At the prime of World War II in 1943, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp humanized David Low’s scathing caricature of the stuffy British political and military establishment whereas, at the same time, they acknowledged how obsolete the ways of the current, archaic administration had become. A Matter of Life and Death in 1946 put forward that the utopia of Heaven was just as constrained by officialdom as bureaucracies on Earth. In 1947 they made Black Narcissus, a film about nuns resisting sexual and spiritual temptations in an Orientalized Himalayan monastery, a conflict which paralleled Britain’s withdrawal from India. Such examples are persistent throughout Powell and Pressburger’s time together, each one confronting the audience with otherwise unspoken but characteristically British concerns.

In The Red Shoes, the filmmakers realign the artistic lifeforce of Britain. As Powell would later assert, “For ten years we had all been told to go out and die for freedom and democracy; but now the war was over, The Red Shoes told us to go out and die for art.” During World War II, the ideal approach to cinema was realism, and yet Powell and Pressburger avoided realism whenever possible. Their consistent embrace of fantasy, from the fluidity of time in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp to the depiction of the afterlife in A Matter of Life and Death, prevailed over realism in subtle, controlled ways. But for The Red Shoes, a new type of fantasy was embraced that harkened the fairy tale origins of Andersen. The original story followed a dancer, who is in effect destroyed for yielding to the lure of her magical red ballet shoes, which reflects the dangers of life imitating the artist’s spiritual self-sacrifice to art. Powell and Pressburger’s picture goes much deeper, using a modern ballet’s backstage drama to explore the infectious, crushing power of art. And what art but dance could better illustrate how art consumes the mind enough to control the body? No other form of art has the corporeal presence of dance or could better show the consuming power of art over the artist.

When Pressburger returned to his earlier screenplay, he expanded his story from a rather straightforward, modernized adaptation of Andersen’s tale into one fully submerged in the passions of artists. From the moment when dancer Léonide Massine peers through the curtain from the backstage of the opening ballet, looking over the watchful audience, the viewer enters a surreal world of the artist. The spectators see only a closed red curtain and remain detached from the dancers’ connection to music or the conductor’s keen eye for dance—all except young musician Julian Craster (Marius Goring) and amateur dancer Victoria Page (Moira Shearer). Before long, Julian and Vicky enter the circle of Boris Lermontov (Anton Walbrook), a devilish ballet impresario, seeking merely to perform their art. But The Ballet Lermontov demands that dance be treated like a religion, with blind devotion to its cause. From his evident talent, Julian is hired as a deputy composer. The result of Vicky’s audition is less substantial, though her exchange with Lermontov confirms they share a mutual lust for dance. Their lives are art and so art is life, as described when Lermontov asks Vicky, “Why do you want to dance?” and she replies “Why do you want to live?”

Though Julian and Vicky have earned positions under the world’s foremost ballet producer, they cannot yet comprehend the extent of his control. Lermontov’s top ballerina (Ludmilla Tchérina) leaves the ballet to be married, but Lermontov thinks only of how her leaving with interrupt his ballet. “Life” is secondary to dance when life itself is defined through dance. Without a star performer, Lermontov allows Vicky to headline in his latest production, an adaptation of Andersen’s The Red Shoes, with original music by Julian. Vicky struggles with her role as the girl subdued by enchanted shoes; Lermontov forces her to listen to Julian’s music during her meals and breaks, embedding its framework into her mind. The first performance of the ballet proves sublime. Lermontov’s troupe soon tours the world, making Vicky a star. As they tour, from the undeniable bond between his music and her dancing, Vicky and Julian fall in love.

Out of jealousy, and under the pretense of concern for his ballet, when Lermontov learns of the romance he angrily casts out Julian, and Vicky follows. The ever immovable Lermontov knows Vicky will never become the great dancer she could be without the Lermontov name backing her, and with time she knows this too. In her outwardly happy married life with Julian, he composes and she stays home; he lives his art and she remains withheld from hers. Only when Lermontov offers Vicky a chance to dance in a revival of The Red Shoes does she feel alive. Julian tries to stop her. He asks her not to dance out of love for him, whereas Lermontov refuses to allow her love but offers her the chance to dance again, which for Vicky is more than love. Though devastated by the choice she knows she must make, she cannot help but choose dance over Julian. “Life is so unimportant,” Lermontov reassures, while, ever the pusher, motioning to his assistant to bring the brokenhearted Vicky her red dancing shoes. “And from now onwards, you will dance like nobody ever before.” Her art-Self conflicted with the part of her that loves Julian, Vicky weeps yet feels compelled to dance. She exists now as a conduit for her art and finds herself bewitched by the red shoes. But rather than move toward the stage, her feet take her outside where she leaps from a veranda to her death.

The magnificent authenticity behind Powell and Pressburger’s film appears in their use of actual ballet dancers in the primary roles, giving every dance sequence and every rehearsal a genuine quality. The famous Royal Ballet at Sadlers Wells, founded by Ninetter de Valois in 1931, trained the film’s choreographer Robert Helpmann and star Moira Shearer. Helpman arrived at the Royal Ballet in 1933 from Australia as a dancer and choreographer, developing the institution into a monument of art culture by the 1940s that instructed dancers with rare and uncharacteristic personalities, dancers capable of dramatic acting in their roles. Shearer was dancing on Helpmann’s production of Miracle in Gorbals when Powell first saw her and offered her the leading role in his new film. And it was her personality that attracted him, whereas within Shearer’s role as Vicky, the opposite becomes true: Lermontov admires Vicky’s talent but seeks to eradicate individuality from his dancers, and by erasing her personality, she becomes a blank canvas for the art of dance. In The Red Shoes, however, Shearer’s portrayal is not so much a performance as it is an embodiment of the passions of dance.

Lermontov was based in part on Sergei Diaghilev, the legendary Russian ballet producer. Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes arrived in Paris in 1909 and its popularity spread to Britain by 1911, ushering a new populist ballet throughout Europe that was, at first, characteristically Russian, but slowly became more European as Diaghilev found dancers of international origins. His troupe traveled about Europe like nomads, moving to the next venue where their art was worshiped and its fame widespread. Not merely embracing dance, Diaghilev combined dance, music, and production design into a modern synthesis that rendered classical ballet an outdated variety. Diaghilev’s finest dancer was Vaslav Nijinsky, a Russian of Polish descent, whose every movement on and offstage was monitored by Diaghilev in a way not unlike how Lermontov keeps strict control over Vicky. Though Lermontov’s onscreen persona was based on Diaghilev, Powell and Pressburger also incorporated their experiences with Hungarian producer Alexander Korda, whose behavior was just as coldly ambitious as Lermontov. Pressburger’s script even placed much of Powell into Lermontov, in the sense that Diaghilev, Korda, Powell, and Lermontov each stand over their productions as authoritarian figures. Powell, in particular, was well aware of his station as director, the overseer of a production on which he was the absolute center. He wrote in his autobiography, “The camera and its crew are no longer that bunch of people out there, but an extension of my own eyes and arms and head.” Seeing himself as the orchestrator of the film production, a position that offers him immeasurable control from behind the camera, Powell later made allusions to his fascination with this power when he played the father role in his 1960 film Peeping Tom, teaching his character’s son Mark the authority of the voyeuristic camera. For all its mystery and subtlety, Walbrook’s wonderful, enigmatic performance as Lermontov nonetheless exudes despotic pride that dare not be challenged. Powell aspired for the same level of control over his films; although, he was decidedly more humane to his cast and crew.

Lermontov was based in part on Sergei Diaghilev, the legendary Russian ballet producer. Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes arrived in Paris in 1909 and its popularity spread to Britain by 1911, ushering a new populist ballet throughout Europe that was, at first, characteristically Russian, but slowly became more European as Diaghilev found dancers of international origins. His troupe traveled about Europe like nomads, moving to the next venue where their art was worshiped and its fame widespread. Not merely embracing dance, Diaghilev combined dance, music, and production design into a modern synthesis that rendered classical ballet an outdated variety. Diaghilev’s finest dancer was Vaslav Nijinsky, a Russian of Polish descent, whose every movement on and offstage was monitored by Diaghilev in a way not unlike how Lermontov keeps strict control over Vicky. Though Lermontov’s onscreen persona was based on Diaghilev, Powell and Pressburger also incorporated their experiences with Hungarian producer Alexander Korda, whose behavior was just as coldly ambitious as Lermontov. Pressburger’s script even placed much of Powell into Lermontov, in the sense that Diaghilev, Korda, Powell, and Lermontov each stand over their productions as authoritarian figures. Powell, in particular, was well aware of his station as director, the overseer of a production on which he was the absolute center. He wrote in his autobiography, “The camera and its crew are no longer that bunch of people out there, but an extension of my own eyes and arms and head.” Seeing himself as the orchestrator of the film production, a position that offers him immeasurable control from behind the camera, Powell later made allusions to his fascination with this power when he played the father role in his 1960 film Peeping Tom, teaching his character’s son Mark the authority of the voyeuristic camera. For all its mystery and subtlety, Walbrook’s wonderful, enigmatic performance as Lermontov nonetheless exudes despotic pride that dare not be challenged. Powell aspired for the same level of control over his films; although, he was decidedly more humane to his cast and crew.

Powell’s control over every detail of The Red Shoes becomes palpable when Vicky first performs ‘The Ballet of the Red Shoes’ onstage, the sequence where Powell and Pressburger test the fabric of their cinematic reality and determine that art contains a fantasy quality. In the artist’s world of the ballet, miracles occur onstage. Designer Hein Heckroth conceived the pivotal ballet sequence that grows from a stage production into a nightmarish dream, at once transcending medium and planes of existence within the story. Using every creative faculty at his disposal, Heckroth assisted Powell in a pure benchmark of cinematic multi-sensory applications, where music, camera movement, lighting, and editing combine into a single expression. The designer’s enthusiasm for ballet and opera fills every moment, as jarring backdrops fade into one another, and as Shearer’s graceful movements guide the eye from set piece to eye-popping set-piece. Powell edited the sequence, along with editor Roger Mills, cutting according to signals in the music such as tempo and melodic pauses, to create a natural current through the mass of visual and auditory stimuli.

The ballet moves from a typical stage setting to Heckroth’s surrealist painted backdrops, into a world where a church of dramatically elongated shapes towers overhead. The ballet’s initial state takes place in what might outwardly be perceived as reality, but the cinematic world, both in the story and where the ballet advances, is not reality. Vicky’s character moves because the red shoes compel her to and because the twisted shoemaker (Massine) controls them like a puppeteer. Notice how the red shoes tie themselves onto Vicky’s feet, or how all at once Vicky sees the ballet’s shoemaker character as both Lermontov and Julian, both her puppeteers in life. Through the sequence, which comes from Vicky’s perspective, the film breaks down reality as the false front, and then exposes the emotional truth underneath as the fantasy world of Vicky’s creation. The film is no longer a peek into The Ballet Lermontov’s backstage workings; the sequence is as much a voyage into Vicky’s mind as it is a rendering of the ballet. Her dancing travels beyond space and time to engage the imagination, flowing together with a flawless unity of music and image. This colorful, limitless universe is where Vicky exists when she dances.

Vicky’s possession by art transforms her from an aspiring performer to an accomplished dancer, until she transmigrates into something else altogether: an unhinged vessel seized by art, thrust into a nightmare world from which there is no escape until her death in the finale. The rapture for art felt by Vicky, and other characters in the film, mirrors Andersen’s original story. Julian, for example, loses himself in a haze but for a moment when Lermontov asks him to adapt The Red Shoes, perhaps out of intoxication with the piece’s unearthly magic. Not even Lermontov is immune to such raptures. After convincing his star dancer to leave her husband and perform The Red Shoes one last time, Lermontov has a moment alone as Vicky heads toward the stage. His cold exterior ruptures in bliss, as for an impresario like Lermontov, assembling a glorious ballet is comparable to Vicky dancing or Julian conducting a fine piece of music. Lermontov’s art rests in managing talent, and his ability to bring talent together in incredible ways is why he remains devoted to his cause. It is his life.

For Powell and Pressburger, art imprisons as much as it liberates. When Vicky gives herself to her art for what will be her final performance, art consumes her and dissolves her autonomy. Throughout the film, when Vicky makes her most important connections with her dancing, she is frenzied by sheer art-ecstasy; Shearer’s eyes become wide and crazed, as if overcome by some spectral being. At the same time, Vicky’s elation leaves her in a state of non-living, as though her body has become a marionette and Art pulls the strings. After she leaps to her death, the ballet is performed one more time in her honor. Vicky is replaced by the white circle of a spotlight. The audience, both the film’s viewer and that in the film, attempts to fill the empty space with a mental projection of Vicky or Moira Shearer. And it becomes a tragic truth that in attempting to replace the image of the character or actor, the audience sees her as a mere ingredient of the ballet rather than a subject, and that through her de-individualization, her artistic outlet did the very opposite of what art is commonly believed to do.

If not for the mystical possession of Vicky by her art, the story could be mistaken for pure melodrama; but the indefinable miracles in even Powell and Pressburger’s most modest, seemingly realist works provide an element of fantasy. In its simultaneous realist and fanciful approaches, where the backstage activities are examined while the ballet sequence uses an array of filmmaking techniques to astound the audience with its magic, The Red Shoes has been considered at war with itself. As such, audiences find a tension between its realism and fantasy, leaving the film as baffling as films get in formal terms. And yet, consider this alternative: Powell and Pressburger have made a rare motion picture that combines a range of technical tricks to construct a work of pure cinema, which in their hands denotes a combination of varied formal elements to accomplish a single reaction from the audience: wonder for art. Considered a commercial failure in Britain, The Red Shoes nonetheless enjoyed an uninterrupted two-year run at The Bijou in New York City. While making commercial films within the British studio system, The Archers remained dedicated to aesthetic ideals that gathered common audiences, their goal being to reinvigorate a sense of wonder about the cinema.

With its narrative communicated through mise-en-scène rather than dialogue, the typical device for the majority of British cinema, Powell and Pressburger’s film is pure art, surely among the most prestigious of cinema’s high-art samplings. But the outcome avoids becoming an inaccessible art-house film. The Red Shoes, if anything, converts the general audience; even the most cynical viewer cannot help but find themselves dazzled by the beauty of the production and the haunting nature of the narrative. In its material and conceptual presence, The Red Shoes rekindles ideals of imagery over voice that Powell had sought since he first witnessed, with much irritation, the arrival of talkies and the dominance of words over visual composition. With The Red Shoes and their next film, The Tales of Hoffman (1951), and to a degree the expanse of their entire oeuvre, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger search for a return to composed forms, to the unification of dialogue, music, and visuals together in a singular cinematic expression of art. Through The Red Shoes, audiences feel the artistic possibility of cinema with that same sense of unhinged passion as Vicky does her dancing, as The Archers succeeded in returning a rarely experienced sense of rapture to the moviegoing masses.

With its narrative communicated through mise-en-scène rather than dialogue, the typical device for the majority of British cinema, Powell and Pressburger’s film is pure art, surely among the most prestigious of cinema’s high-art samplings. But the outcome avoids becoming an inaccessible art-house film. The Red Shoes, if anything, converts the general audience; even the most cynical viewer cannot help but find themselves dazzled by the beauty of the production and the haunting nature of the narrative. In its material and conceptual presence, The Red Shoes rekindles ideals of imagery over voice that Powell had sought since he first witnessed, with much irritation, the arrival of talkies and the dominance of words over visual composition. With The Red Shoes and their next film, The Tales of Hoffman (1951), and to a degree the expanse of their entire oeuvre, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger search for a return to composed forms, to the unification of dialogue, music, and visuals together in a singular cinematic expression of art. Through The Red Shoes, audiences feel the artistic possibility of cinema with that same sense of unhinged passion as Vicky does her dancing, as The Archers succeeded in returning a rarely experienced sense of rapture to the moviegoing masses.

Bibliography:

Christie, Ian. Arrows of Desire: The Films of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. Faber & Faber, 1994.

Christie, Ian. Powell, Pressburger and Others. BFI (British Film Institute), 1978.

Christie, Ian and Moor, Andrew, eds. The Cinema of Michael Powell. BFI (British Film Institute), 2005.

Moor, Andrew. Powell and Pressburger: A Cinema of Magic Spaces (Cinema and Society). I.B. Tauris; Distributed in the U.S. by Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

Powell, Michael. A Life In Movies: An Autobiography. Heinemann, 1986.

Powell, Michael. Million Dollar Movie. Heinemann, 1992.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review