The Definitives

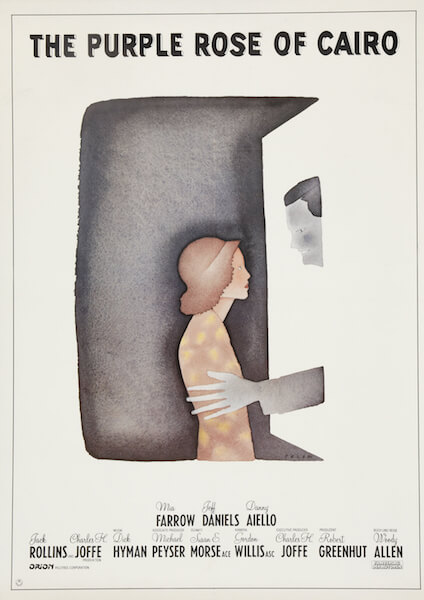

The Purple Rose of Cairo

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Up on the screen, anything is possible. Egyptian adventures, upper-crust hobnobbing, a night out in the big city, fine clothes, expensive cocktails at even more expensive nightclubs, and oh—what romance! In Woody Allen’s The Purple Rose of Cairo, a young woman in the Great Depression, an era in which millions of moviegoers escaped their dreary lives by going to glamorous Hollywood movies, sees the same picture over and over. On her fifth time around, the film’s most adventurous character appears unduly distracted; he seems to notice her, and then he breaks from the scene to admit seeing her at screenings before. “Me?” she says in disbelief. “You mean me?” All at once, the film character steps from the black-and-white screen and into her color world. Other theater patrons gasp and faint in astonishment. How such a thing could come to pass it does not matter. She has long dreamt about meeting some impossibly adventurous and romantic character from the movies, and now her dream has come true.

Balanced with equal measures of whimsy and melancholy, The Purple Rose of Cairo considers how cinema grants an escape from the real world. When the adventurer takes the moviegoer by the hand and runs off with her, their escapades begin. Yet, Allen’s comedy is not about pure escapism; he also carefully weighs the consequences of fantasy fulfillment. Using his plot device as a springboard to explore how movies and reality differ, there are comic moments where the screen character realizes the real world is far more complicated than his own, while the woman comes to find how naïve movies are to the real world. One of the funniest moments in the film occurs when this fantasy character kisses her, pauses, then asks, “Where’s the fade-out? … Always when the kissing gets hot and heavy, just before the lovemaking, there’s a fadeout.” She explains that this is not how her world works, which leads to a perfect line when she admits to her sister, “He’s fictional, but you can’t have everything.”

In the film’s Depression-era setting, terminally gray skies hang over waifish Cecelia, played by Mia Farrow with her meek but sparkling quality. A clumsy waitress inclined to dropping plates at the local greasy spoon, she comes home to her unemployed and unfaithful husband, Monk (Danny Aiello), a lug who spends his days playing dice. After a few beers, he has a tendency to knock her around. “I only hit you when you get out of line,” he justifies. “And I never just hit you. I always warn you first.” Cecelia’s only respite comes from the Jewel Theater, a moviehouse where she spends her nickel to catch the latest picture, oftentimes more than once. The latest from RKO is a romp called “The Purple Rose of Cairo”, wherein young adventurer Tom Baxter (Jeff Daniels), complete with a pith helmet and twinkle in his eye, heads out on a “madcap Manhattan weekend” with his new high society friends. After Cecelia settles down for her fifth viewing, Tom Baxter steps off the screen to make her dreams come true. Allen’s only explanation as to how such a thing could occur: “It’s New Jersey. Anything can happen.”

In the film’s Depression-era setting, terminally gray skies hang over waifish Cecelia, played by Mia Farrow with her meek but sparkling quality. A clumsy waitress inclined to dropping plates at the local greasy spoon, she comes home to her unemployed and unfaithful husband, Monk (Danny Aiello), a lug who spends his days playing dice. After a few beers, he has a tendency to knock her around. “I only hit you when you get out of line,” he justifies. “And I never just hit you. I always warn you first.” Cecelia’s only respite comes from the Jewel Theater, a moviehouse where she spends her nickel to catch the latest picture, oftentimes more than once. The latest from RKO is a romp called “The Purple Rose of Cairo”, wherein young adventurer Tom Baxter (Jeff Daniels), complete with a pith helmet and twinkle in his eye, heads out on a “madcap Manhattan weekend” with his new high society friends. After Cecelia settles down for her fifth viewing, Tom Baxter steps off the screen to make her dreams come true. Allen’s only explanation as to how such a thing could occur: “It’s New Jersey. Anything can happen.”

At first, Cecelia loses herself in the impossibility of it all after Tom promises her a better life, starting with dinner and dancing. They set out to an expensive restaurant but quickly find Tom’s riches are prop money. When they rush out to ditch the bill, Cecelia follows Tom into a car where they hope to make a fast getaway, but having only driven in movies, he has no idea how to start a car. Faced with everyday limitations, suddenly a heroic movie character struggles to carry out Cecelia’s fantasy. And when they kiss, well, Tom has no idea what goes on after the fade-out. When the screen goes black, or the married couple set their shoes outside the bedroom door, or the bedroom window closes, what happens? Cecelia, returning to work the next day, leaves Tom to hide out in the abandoned fairgrounds. There, a prostitute (Dianne Wiest, in her first of several roles in Allen films) picks him up and brings him back to her brothel, where a gaggle of entranced working girls find his naïveté endearing. They decide to give him one on the house, but he resists out of his blind love for Cecelia. The hookers all but swoon. If only there were more guys out there like Tom Baxter; but the sad fact is no man like him has ever existed outside of fiction. And so, Cecelia’s wish may have come true, but it lacks a concrete place in reality.

Allen’s film earns comparisons to great surrealist masterworks, like Luis Bunuel’s The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (which has been referenced multiple times in Allen’s oeuvre), as everyone onscreen accepts this fantastical event with Tom Baxter and hopes to deal with it in logical terms. When the film’s producer Raoul Hirsch (Alexander H. Cohen) catches wind of the incident, he panics and threatens to pull all prints from their vendors unless Baxter’s actor, Gil Shepherd (also Daniels), can convince his own character to return to the screen. Several moviehouses across the country have experienced similar events like the one in New Jersey, and Shepherd must contain the situation to save his career. Meanwhile, back at the Jewel, the projector runs continuously. Some moviegoers just sit and watch, waiting to see what will happen next. Tom’s fellow screen characters (Zoe Caldwell, Ed Herrmann, John Wood, Van Johnson, and Milo O’Shea) sit about their unmoving shot, playing cards and griping about their circumstances, as their performance cannot proceed until Tom returns. And though “The Purple Rose of Cairo” will not continue, a paying audience sits and waits, because at least it’s something to avert their minds from reality.

Allen’s film earns comparisons to great surrealist masterworks, like Luis Bunuel’s The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (which has been referenced multiple times in Allen’s oeuvre), as everyone onscreen accepts this fantastical event with Tom Baxter and hopes to deal with it in logical terms. When the film’s producer Raoul Hirsch (Alexander H. Cohen) catches wind of the incident, he panics and threatens to pull all prints from their vendors unless Baxter’s actor, Gil Shepherd (also Daniels), can convince his own character to return to the screen. Several moviehouses across the country have experienced similar events like the one in New Jersey, and Shepherd must contain the situation to save his career. Meanwhile, back at the Jewel, the projector runs continuously. Some moviegoers just sit and watch, waiting to see what will happen next. Tom’s fellow screen characters (Zoe Caldwell, Ed Herrmann, John Wood, Van Johnson, and Milo O’Shea) sit about their unmoving shot, playing cards and griping about their circumstances, as their performance cannot proceed until Tom returns. And though “The Purple Rose of Cairo” will not continue, a paying audience sits and waits, because at least it’s something to avert their minds from reality.

As the film defines Allen’s enduring preference for reality over fantasy, his mise-en-scène employs simple details to differentiate the two. Throughout his narrative, realism is portrayed through formulaic descriptions but nevertheless effective dramatic clichés: the abusive husband, the clumsy waitress, hookers with hearts of gold, hard times, and so forth. Cinematographer Gordon Willis and production designer Stuart Wurtzel render the period without the usual glamour of 1930s-set films. Colors are intentionally drab and flat. Period details remain in the background. Any kind of formal romanticism exists only on the film-within-the-film, where Allen and Willis recreate the look and feel of a Golden Age talkie. Still, Allen forgoes grittier historical details about the Great Depression by, ironically enough, breezing over them as any Hollywood film from that era would have. The film’s most brilliant stroke of realism is not part of the presentation, however; it lies within the dramatic authenticity of Allen’s conclusion, and his refusal to manufacture a fabricated “happy ending” for Cecilia.

When Shepherd arrives in New Jersey, he searches for the escaped Tom Baxter but finds Cecelia instead. Love seems to strike immediately with Gil, a straight-laced everyman’s actor whose Joel McCrea quality affords him charm. For Cecelia, meeting a real-life Hollywood movie star has some sense of tangibility, a genuine chance to fulfill her fantasies of escape, more certainly than with Tom. Even though Tom takes her inside his black-and-white world on the screen, where she experiences that “madcap Manhattan weekend” she has so often dreamt about, the experience is not what she expected. It’s wonderful, but the champagne is merely ginger ale, the night passes by in montage, and none of it’s in Technicolor. But then, Gil arrives in the theater and promises to take Cecelia back to Hollywood with him. A real adventure, and in color to boot! She chooses the real world with Gil and, broken-hearted, Tom steps back into the movie screen.

When Shepherd arrives in New Jersey, he searches for the escaped Tom Baxter but finds Cecelia instead. Love seems to strike immediately with Gil, a straight-laced everyman’s actor whose Joel McCrea quality affords him charm. For Cecelia, meeting a real-life Hollywood movie star has some sense of tangibility, a genuine chance to fulfill her fantasies of escape, more certainly than with Tom. Even though Tom takes her inside his black-and-white world on the screen, where she experiences that “madcap Manhattan weekend” she has so often dreamt about, the experience is not what she expected. It’s wonderful, but the champagne is merely ginger ale, the night passes by in montage, and none of it’s in Technicolor. But then, Gil arrives in the theater and promises to take Cecelia back to Hollywood with him. A real adventure, and in color to boot! She chooses the real world with Gil and, broken-hearted, Tom steps back into the movie screen.

For much of The Purple Rose of Cairo, Allen’s tightly wound pacing and clever jokes keep us laughing and in tune with Cecelia’s love of escapist cinema. His characters frolic about the screen, chasing fantastical dreams in impossible situations, the promise of flight from Cecelia’s harsh reality all but assured. Gil having promised to take her to Hollywood, she leaves Monk and worries not about being fired from her job. She waits for Gil in front of the theater, and waits, but he never arrives. With Tom Baxter back on the screen and “The Purple Rose of Cairo” pulled from distribution, Gil Shepherd’s career can carry on. Cecelia has been abandoned. Returning home now would be almost inconceivable; her fantasy man has gone back to his fantasy world; her real-life beaux has deserted her; she has no job and ultimately no hope. All she can do is spend her last bit of change on the moviehouse’s latest, Top Hat, in which Fred Astaire sings “Dancing Cheek to Cheek” to Ginger Rogers. The lyrics “I’m in heaven” call out in irony as Cecelia settles into her seat and, despite her misfortune, forgets her troubles in the light of the silver screen. For Cecelia, Allen’s outlook amounts to unflinching despair. In all likelihood, she will probably return to her old life with Monk, where she will once again become his punching bag, personal cook, and doormat. As he said earlier in the film, “It may take a week. It may take an hour. But you’ll be back!” Who can say? Whatever Cecelia’s fate, it will be no fantasy.

The Purple Rose of Cairo takes influence from Fellini’s The White Sheik and Buster Keaton’s Sherlock, Jr., where the lines of reality and movie fantasy are blurred. This is often the case in Allen’s work: In his stage piece Play It Again, Sam, Allen’s character interacts with Casablanca’s Rick Blaine. In an early short story, The Kugelmass Episode, a professor becomes so taken with Madame Bovary that he wills himself into Flaubert’s novel. Consider Allen’s only musical to date, Everyone Says I Love You (1997), in which Julia Roberts’ unhappily married character meets her fantasy man, and though at first taken by his complete fulfillment of her deepest desires, she ultimately returns to her imperfect husband, saying that because she has now lived out her fantasy, she no longer has to dwell on her unfulfilled dreams and can live happily with her husband. Or consider Midnight in Paris (2011), where Owen Wilson’s unhappily engaged screenwriter finds himself transported to “The City of Light” in the 1920s, the period of his dreams, where he mixes with his idolized writers and artists. There, he falls in love with Picasso’s muse (Marion Cotillard) and discovers that she too romanticizes the past, specifically the 1890s Belle Époque. In her, he sees reflected his own dissatisfaction with modernity and how people have always romanticized the past; and rather than embrace nostalgia, he resolves to improve his present. As much as Allen acknowledges how art and nostalgia help us escape, time and again he emphasizes how a grounded place in reality remains ever vital.

The Purple Rose of Cairo takes influence from Fellini’s The White Sheik and Buster Keaton’s Sherlock, Jr., where the lines of reality and movie fantasy are blurred. This is often the case in Allen’s work: In his stage piece Play It Again, Sam, Allen’s character interacts with Casablanca’s Rick Blaine. In an early short story, The Kugelmass Episode, a professor becomes so taken with Madame Bovary that he wills himself into Flaubert’s novel. Consider Allen’s only musical to date, Everyone Says I Love You (1997), in which Julia Roberts’ unhappily married character meets her fantasy man, and though at first taken by his complete fulfillment of her deepest desires, she ultimately returns to her imperfect husband, saying that because she has now lived out her fantasy, she no longer has to dwell on her unfulfilled dreams and can live happily with her husband. Or consider Midnight in Paris (2011), where Owen Wilson’s unhappily engaged screenwriter finds himself transported to “The City of Light” in the 1920s, the period of his dreams, where he mixes with his idolized writers and artists. There, he falls in love with Picasso’s muse (Marion Cotillard) and discovers that she too romanticizes the past, specifically the 1890s Belle Époque. In her, he sees reflected his own dissatisfaction with modernity and how people have always romanticized the past; and rather than embrace nostalgia, he resolves to improve his present. As much as Allen acknowledges how art and nostalgia help us escape, time and again he emphasizes how a grounded place in reality remains ever vital.

Released in 1985, The Purple Rose of Cairo was only the second of Allen’s directorial efforts in which he did not star, after Interiors (1978). During production, executives from the now-defunct Orion Pictures, Allen’s home base from the late ‘70s to early ‘90s, put up an unusual resistance to this film. To begin with, they wanted Allen to star, but he originally cast Michael Keaton as both Baxter and Shepherd. The production shot 10 days worth of footage before Allen opted to replace Keaton, admitting the actor’s onscreen persona was too contemporary, whereas Daniels carries a kind of blind innocence appropriate to Baxter, and fittingly deceiving for Shepherd. For a sense of personal nostalgia, the production filmed cinema interiors at Brooklyn’s Kent Theater, a last-run moviehouse where Allen spent much of his time as a boy. After filming wrapped and the executives saw the initial cut, they wanted Allen to reshoot the ending to deliver a crowd-pleaser instead. Allen, who once said the whole reason he made the film was for the ending, exercised his long-practiced creative control over his projects and refused the studio’s request. Years later, when interviewed about the film, Allen, his own harshest critic, said that The Purple Rose of Cairo remains among his favorites of his own works, being that his films so rarely turn out as they were originally conceived, but this one turned out “fairly close”.

However heartbreaking a conclusion, Allen’s film is a loving journey into the power of movies—not only the Golden Age of Hollywood filmmaking, but the ability of all movies to make us forget the world outside. In our most miserable times, they carry us away so completely. The darkened theater shrouds our complex or sad lives and a feeling of safety blankets us. And though that security may be tested by the film, we always know we’ll be safe. When a moviegoer like Cecelia has nothing else, at least she has the cinema. Allen’s sentiments are not those of a highbrow art film enthusiast, but as a watcher of mainstream movies whose purpose it is to entertain. They serve the specific and necessary function by allowing us to cope with the horrible real world through fantasy. And later, they become landmarks in our memory, a theme Allen investigates further in Radio Days (1987), which also stars Mia Farrow and Jeff Daniels in smaller roles. There are films we see that burn into our minds and remembrances, while others help define how we see ourselves and help us change. One easily recalls how frightened Jaws first made them, how mystified they felt after their original viewing of 2001: A Space Odyssey, or how much they laughed and felt during Annie Hall. At the moment we see a film, it transcends its meaning through our memory. This is the value of great art.

However heartbreaking a conclusion, Allen’s film is a loving journey into the power of movies—not only the Golden Age of Hollywood filmmaking, but the ability of all movies to make us forget the world outside. In our most miserable times, they carry us away so completely. The darkened theater shrouds our complex or sad lives and a feeling of safety blankets us. And though that security may be tested by the film, we always know we’ll be safe. When a moviegoer like Cecelia has nothing else, at least she has the cinema. Allen’s sentiments are not those of a highbrow art film enthusiast, but as a watcher of mainstream movies whose purpose it is to entertain. They serve the specific and necessary function by allowing us to cope with the horrible real world through fantasy. And later, they become landmarks in our memory, a theme Allen investigates further in Radio Days (1987), which also stars Mia Farrow and Jeff Daniels in smaller roles. There are films we see that burn into our minds and remembrances, while others help define how we see ourselves and help us change. One easily recalls how frightened Jaws first made them, how mystified they felt after their original viewing of 2001: A Space Odyssey, or how much they laughed and felt during Annie Hall. At the moment we see a film, it transcends its meaning through our memory. This is the value of great art.

Of all films about the power of cinema, The Purple Rose of Cairo explores its subject most tenderly, radiating a warm truth in a scenario both surreal and farcical. Allen’s customary witticisms and observations give the film a playful quality reminiscent of his early-career comedies, but his profoundly affecting conclusion leaves the viewer saddened and reflective, a sense matched only by his most solemn dramas. Contributing to an ongoing tradition of films about film (from Sunset Boulevard, Blow Out, and The Player), Allen investigates what draws audiences into theaters. He understands our longing to dream and escape into those seemingly perfect worlds onscreen, even while his narrative underscores how movies are not real life. Perhaps it remains so relatable and touching for audiences because, after all, who better than an audience to identify with Cecelia’s need to escape? Her love of and necessity for movies provides a sad yet undeniable catharsis, a feeling experienced by anyone who has lost themselves in a great film. How appropriate then that, for a time, Allen recreates such an escapist experience here, yet also confronts us with how the dream ends when the credits roll.

Bibliography:

Allen, Woody; Björkman, Stig. Woody Allen On Woody Allen. New York: Grove Press, 2005.

Blake, Richard A. Woody Allen: Profane and Sacred. University of Michigan: Scarecrow Press, 1995.

Fox, Julian. Woody: Movies from Manhattan. New York: Overlook Press, 1996.

Lax, Eric. Conversations with Woody Allen. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007.

Lax, Eric. Woody Allen: A Biography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review