The Definitives

The Princess Bride

Essay by Brian Eggert |

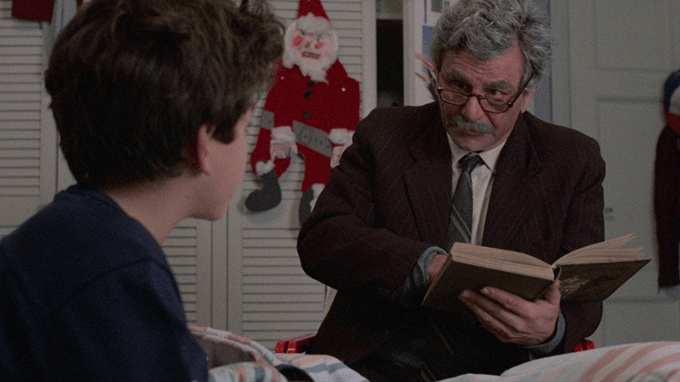

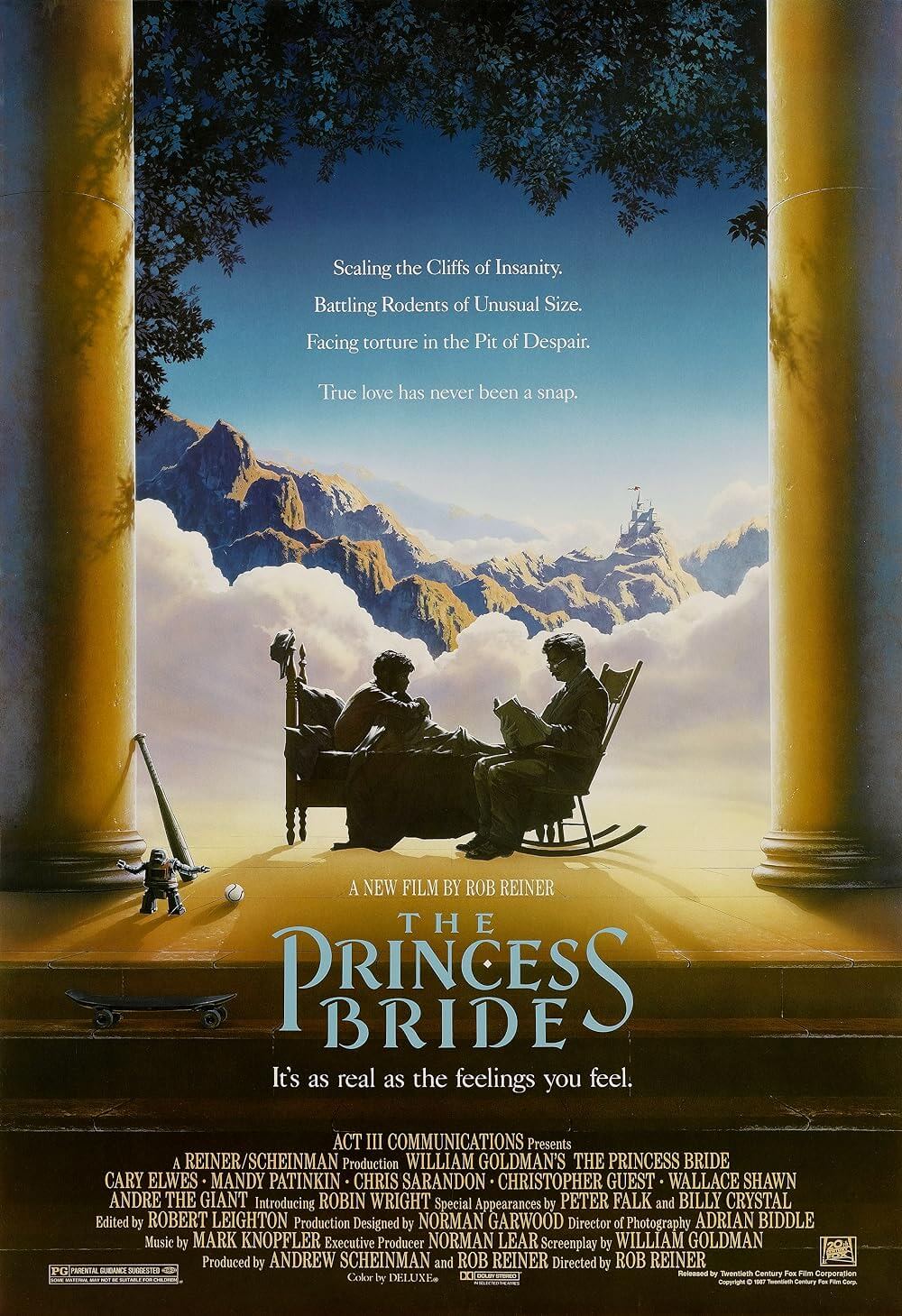

On the original poster for The Princess Bride, columns frame two near-silhouetted figures: a grandfather in a rocking chair, reading a story to his grandson. Orange-yellow light illuminates them from the distance, where your eyes can follow a vast mountain range to a castle atop a peak. In the foreground, the grandson’s toys appear scattered on steps that descend, growing dark enough so the white tagline stands out: “It’s as real as the feelings you feel.” Most involved with the 1987 production believed this promotional artwork failed to adequately sell the film’s irresistible blend of swashbuckling, swooning romance, and deft genre satire. Although the film performed moderately well in its initial theatrical run, it wasn’t a runaway hit. That would come later. So what was this poster selling? A movie about a lovable old fart reading to a sickly kid? Where were the titular Princess Buttercup, the Dread Pirate Roberts, the giant Fezzik, the Spaniard swordsman, and the Rodents of Unusual Size? Where was the romance-for-the-ages between Westley and Buttercup? Audiences didn’t know, unless they had already read the 1973 book, credited to S. Morgenstern for inventing a “Classic Tale of True Love & High Adventure” and abridged by William Goldman. If the poster failed to sell The Princess Bride by Hollywood’s standards, readers of the book probably looked at the poster and smiled knowingly, realizing how perfectly it evokes the text.

There is, of course, no S. Morgenstern. In Goldman’s introduction to the book, he spins a yarn about how his father used to read him The Princess Bride as a child. So he purchased the book and read it to his son, only to realize it was not the book he remembered. Instead, Goldman discovered Morgenstern’s book used fantasy and adventure much in the same manner as Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels—as a political satire, remarking on the times in exaggerated imagery. Goldman’s father had skipped over “sixty pages of text dealing with Prince Humperdinck’s ancestry,” and other serious matters, relaying only the “good parts.” Goldman then claims that he reached out to the publisher and convinced them to grant him the rights to write an abridged version that reflected his father’s edits, much to the dismay of the Morgenstern estate. Goldman also added, in italics, his abridging remarks, including his account of reading Morgenstern’s book to his son. A similar framing device and the question of authorship carry over to Goldman’s screenplay, which tells The Princess Bride through the lens of Peter Falk reading the tale to Fred Savage—a book credited to S. Morgenstern, not Goldman. Grandpa must be skipping the boring parts.

Insomuch that it represents Goldman and his authorship conceit from the book, the film’s poster is brilliant, even if it doesn’t do what posters should: sell the movie. Except, it’s a marvelously accurate rendering of the high-concept premise, painted by John Alvin—the poster artist behind countless iconic movie posters from this era (Blazing Saddles, E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial, The Little Mermaid, Aladdin, Arachnophpbia, etc.). Regardless, time has been kind to The Princess Bride. More than kind. Time has given the film room to blossom into a classic. Following its theatrical run in the late 1980s, the film was watched and rewatched thanks to the popularity and accessibility of VHS cassettes, video rental stores, and cable television. Word of mouth spread. What started as a mild success for 20th Century Fox became universally cherished. The film continues to be celebrated on streaming services and various forms of physical media, and it remains every bit as appealing today as it was in 1987. It’s the rare film that not only holds up after repeated viewings but withstands the scrutiny that can ruin certain movies after you grow out of them. When you reach a certain age, sometimes films that you enjoyed 20-30 years ago seem trite or childish today. The Princess Bride remains just as wonderful today thanks to its simultaneous nostalgia for traditional adventures and its crisp sense of humor that resists winking at the audience or spoiling the integrity of its characters. Few films have ever walked the thin line between earnestness and irony so flawlessly.

Insomuch that it represents Goldman and his authorship conceit from the book, the film’s poster is brilliant, even if it doesn’t do what posters should: sell the movie. Except, it’s a marvelously accurate rendering of the high-concept premise, painted by John Alvin—the poster artist behind countless iconic movie posters from this era (Blazing Saddles, E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial, The Little Mermaid, Aladdin, Arachnophpbia, etc.). Regardless, time has been kind to The Princess Bride. More than kind. Time has given the film room to blossom into a classic. Following its theatrical run in the late 1980s, the film was watched and rewatched thanks to the popularity and accessibility of VHS cassettes, video rental stores, and cable television. Word of mouth spread. What started as a mild success for 20th Century Fox became universally cherished. The film continues to be celebrated on streaming services and various forms of physical media, and it remains every bit as appealing today as it was in 1987. It’s the rare film that not only holds up after repeated viewings but withstands the scrutiny that can ruin certain movies after you grow out of them. When you reach a certain age, sometimes films that you enjoyed 20-30 years ago seem trite or childish today. The Princess Bride remains just as wonderful today thanks to its simultaneous nostalgia for traditional adventures and its crisp sense of humor that resists winking at the audience or spoiling the integrity of its characters. Few films have ever walked the thin line between earnestness and irony so flawlessly.

Goldman’s inspiration for the story bears little resemblance to his narrative framing device in the book. The truth is, Goldman never read The Princess Bride to his son; he never had a son. Instead, the author suggested to his two young daughters, aged 4 and 7, that he would write them a story while on a trip to California, and he asked what it should be about. “Princesses!” one replied, and “Brides!” said the other. Goldman settled on the title right there. He started by writing the first few pages but got hung up on the story. Only after a few years, when he thought of inserting a fictionalized version of himself into the tale, which would be an abridged version authored by another writer, did he return to finish the book. By the time the book was published in 1973 to rave reviews, Goldman was already a well-known author. His first novel, The Temple of Gold, was published in 1957. Over the next decade, he published many more novels until actor Cliff Robertson, who admired Goldman’s work, asked him to rewrite the script for Masquerade (1965), a comic spy yarn distributed by United Artists. After that, Goldman wrote his first original screenplay for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), which he had been researching for years, and earned himself an Academy Award for his effort. He would go on to be one of the most well-respected screenwriters and Hollywood script doctors, penning Marathon Man (1976), All the President’s Men (1976), Magic (1978), Misery (1990), and many others.

Though a prolific author of books, screenplays, plays, memoirs, and nonfiction texts, Goldman considered The Princess Bride to be his favorite of his own works. Not long after the book’s publication, he adapted the property into a screenplay. However, upon shopping his script around Hollywood, he found only a series of rejections and stalled attempts to green-light the project. Studio executives had a difficult time defining the story, which, in Hollywood terms, is poisonous. The project floated around between various studios, all of them afraid to tackle what had been deemed an unfilmable screenplay that could never be marketed. Ironically, the project originated at Fox, which had purchased the rights for Richard Lester (A Hard Day’s Night, 1964) to direct. The deal fell through and, in an unprecedented move, Goldman purchased the rights back from Fox so the material he so adored wouldn’t languish in so-called developmental hell. Then, Goldman pitched the film to various big-name directors, including Norman Jewison, John Boorman, François Truffaut, and Robert Redford, resulting only in false starts and more delays. Not even figures of their clout could crack the film. The film’s eventual producer, Andy Scheinman, recalled a story about the head of Columbia turning down the script, warning, “You’ve got to be careful with William Goldman scripts. He tricks you with good writing.”

Among the directors that Goldman pitched was Carl Reiner, the comedian, writer, actor, and director. The elder Reiner couldn’t figure out the material, but he passed the book and screenplay on to his son, Rob, who was in his twenties at the time. The younger Reiner hadn’t yet become a household name, playing “Meathead” on TV’s All in the Family, but he loved the book. He called it “the best thing I’d ever read.” Years later, Reiner started his directing career. His first film, This Is Spinal Tap (1984), quickly became a comedy classic and provided future writer-director Christopher Guest (Best in Show, 2000) with the mockumentary template for his work. Reiner followed it with The Sure Thing (1985), a profitable teen sex romp, starring John Cusack. Then Reiner achieved overwhelming artistic and commercial success with 1986’s Stand by Me, based on the Stephen King novella The Body. The film was such a hit that Reiner was given veritable carte blanche to develop his next project. He decided on The Princess Bride. After acquiring Goldman’s blessing, Reiner appealed to his former All in the Family producer Norman Lear, who had developed Stand by Me under his new company, Act III Communications. Lear read the script and agreed to finance the production, with the understanding that Reiner would secure distribution with a major studio. The project ultimately landed at 20th Century Fox, where Goldman had originally sold the rights a decade earlier.

Among the directors that Goldman pitched was Carl Reiner, the comedian, writer, actor, and director. The elder Reiner couldn’t figure out the material, but he passed the book and screenplay on to his son, Rob, who was in his twenties at the time. The younger Reiner hadn’t yet become a household name, playing “Meathead” on TV’s All in the Family, but he loved the book. He called it “the best thing I’d ever read.” Years later, Reiner started his directing career. His first film, This Is Spinal Tap (1984), quickly became a comedy classic and provided future writer-director Christopher Guest (Best in Show, 2000) with the mockumentary template for his work. Reiner followed it with The Sure Thing (1985), a profitable teen sex romp, starring John Cusack. Then Reiner achieved overwhelming artistic and commercial success with 1986’s Stand by Me, based on the Stephen King novella The Body. The film was such a hit that Reiner was given veritable carte blanche to develop his next project. He decided on The Princess Bride. After acquiring Goldman’s blessing, Reiner appealed to his former All in the Family producer Norman Lear, who had developed Stand by Me under his new company, Act III Communications. Lear read the script and agreed to finance the production, with the understanding that Reiner would secure distribution with a major studio. The project ultimately landed at 20th Century Fox, where Goldman had originally sold the rights a decade earlier.

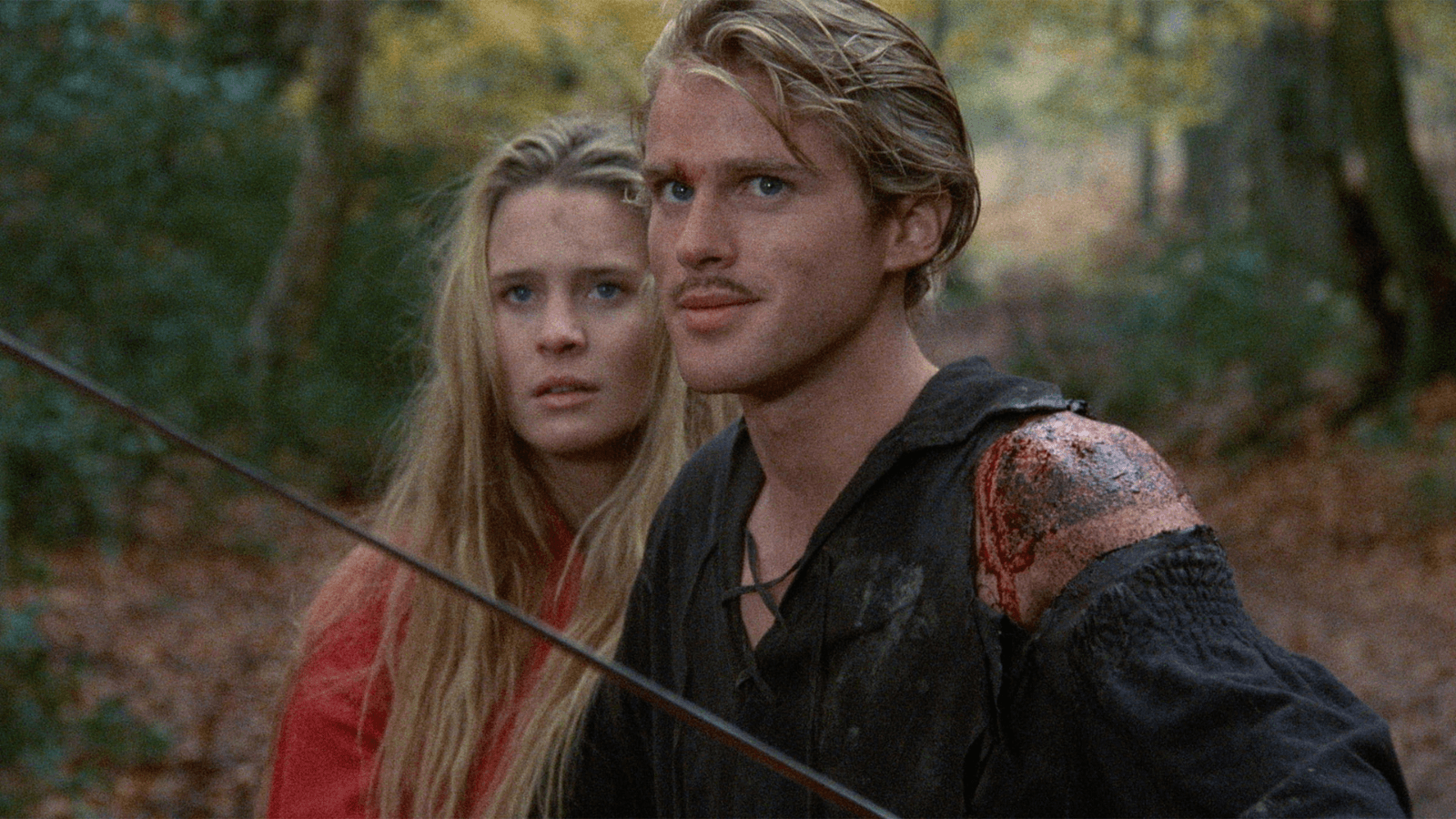

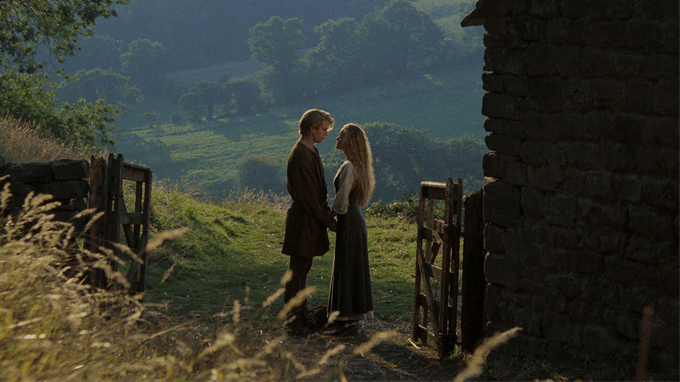

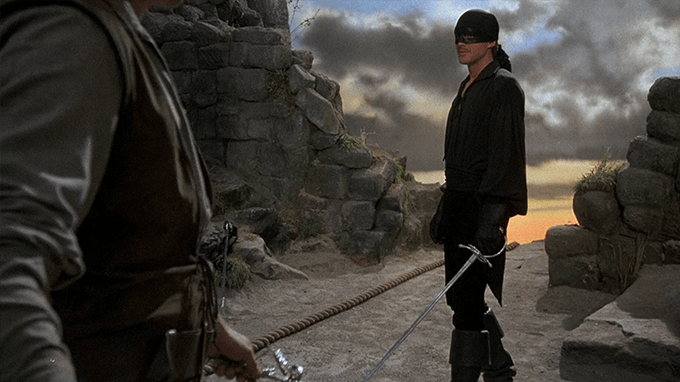

Casting the film became a matter of finding people who could grasp Goldman’s sense of irony without taking the humor too far. Similar to Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland in The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), the performers had to align with their very English surroundings and understand the storybook dynamic. The humor was another aspect entirely and could make or break the performance. “This is a very specialized kind of acting,” Reiner observed. “You have to kind of be very real and earnest, but at the same time there’s a slight tongue-in-cheek thing happening. You have to strike the balance.” At the time, Cary Elwes was a relative unknown, having starred in a few minor film roles, including Lady Jane (1986). But he had a sense of humor that could be calibrated, evidenced by his initial meeting with Reiner and Scheinman, where he did an impression of Bill Cosby and talked of his love of Saturday Night Live. Elwes got the part, and he plays every moment flawlessly. His understated presence suggests a bemusement over every situation—as though Westley or, if you prefer, the Man in Black or the Dread Pirate Roberts, knows what’s coming because he’s read ahead in the text. But he’s also not going to spoil anything for the viewer. That he could restrain himself in The Princess Bride, and then deliver two broad, spoofy performances in Hot Shots! (1991) and Robin Hood: Men in Tights (1993), suggests the precision skill of his comedic acting.

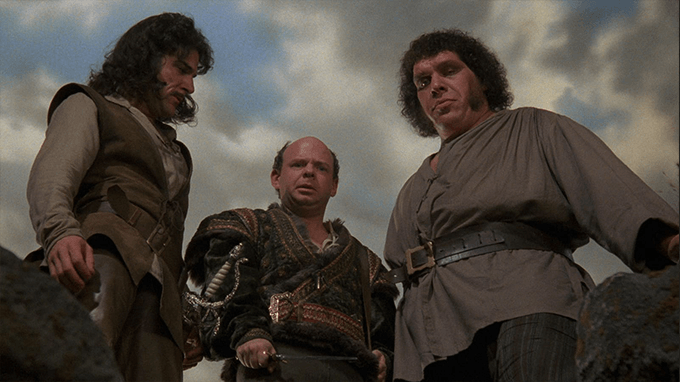

Along with Elwes, most of the roles were cast with the first choice in mind. “For many of the parts, we didn’t have a second choice,” noted Scheinman. Other well-known comedic actors were cast, including This Is Spinal Tap and SNL alumni Billy Crystal and Christopher Guest, who were both friends with Reiner. They played Miracle Max and Count Rugen respectively. Although Goldman had considered Arnold Schwarzenegger in the 1970s, all involved knew French-born professional wrestler André René Roussimoff, known as André the Giant, would be the ideal Fezzik; Goldman wrote the character with André in mind after seeing him wrestle on television. Chris Sarandon, who had read the book when Robert Redford was developing the project in the 1970s, was cast as Prince Humperdinck. Mandy Patinkin was hired to play Inigo Montoya before talks with Elwes, his eventual sparring partner throughout the film, began—giving him a head start on the rigorous fencing lessons. Wallace Shawn would play Vizzini, the clever Sicilian hired by Humperdinck to start a war. Carol Kane was cast as Valerie, the wife of Miracle Max. Peter Cook, Mel Smith, and Willoughby Gray would round out the principal cast. The most difficult role to cast was Princess Buttercup, said to be the most beautiful woman in all the land. To be sure, Reiner saw many beautiful young women who wanted to play the role. But Robin Wright—who, though America, had an English stepfather and could perform the accent—not only looked the part but understood the restrained humor required to play it. “She was literally the only one I saw who could play the role,” attested Reiner.

With a modest budget of $16 million and an ambitious number of storybook set pieces, Reiner set out to shoot the picture on location in England and Ireland, while the legendary Shepperton Studios became home to the Fire Swamp, Cliffs of Insanity, Pit of Despair, and castle sets, among others. The cast wore costumes by British designer Phyllis Dalton, who had worked with David Lean and Carol Reed, and later Terry Gilliam and Kenneth Branagh. Cinematographer Adrian Biddle, who received his start at RSA, Ridley Scott’s advertising company, and who collaborated with Scott on many of his subsequent features, shot the film with classically informed colors and lighting. While shooting, according to Elwes, the actor was responsible for conceiving several pieces of physical humor and derring-do, including Fezzik using Westley’s head like a marionette and the head-first dive into quicksand (performed by a stuntman). Aside from a few snafus, the production was relatively free of drama. In his introduction to the 30th Anniversary Edition of his book, Goldman admits that he doesn’t feel comfortable on movie sets and rarely watches the production of his scripts. But he recounts being on set during the filming of the Fire Swamp scene, and how he ruined a take when he panicked over Buttercup’s dress catching fire. “It’s supposed to catch fire,” Reiner told the author, who then retreated sheepishly. Other than Elwes injuring his foot after André the Giant encouraged him to take an ill-advised ride on his personal ATV, and Guest knocking out Elwes after striking him too hard with a sword, much of the filming went by without incident.

With a modest budget of $16 million and an ambitious number of storybook set pieces, Reiner set out to shoot the picture on location in England and Ireland, while the legendary Shepperton Studios became home to the Fire Swamp, Cliffs of Insanity, Pit of Despair, and castle sets, among others. The cast wore costumes by British designer Phyllis Dalton, who had worked with David Lean and Carol Reed, and later Terry Gilliam and Kenneth Branagh. Cinematographer Adrian Biddle, who received his start at RSA, Ridley Scott’s advertising company, and who collaborated with Scott on many of his subsequent features, shot the film with classically informed colors and lighting. While shooting, according to Elwes, the actor was responsible for conceiving several pieces of physical humor and derring-do, including Fezzik using Westley’s head like a marionette and the head-first dive into quicksand (performed by a stuntman). Aside from a few snafus, the production was relatively free of drama. In his introduction to the 30th Anniversary Edition of his book, Goldman admits that he doesn’t feel comfortable on movie sets and rarely watches the production of his scripts. But he recounts being on set during the filming of the Fire Swamp scene, and how he ruined a take when he panicked over Buttercup’s dress catching fire. “It’s supposed to catch fire,” Reiner told the author, who then retreated sheepishly. Other than Elwes injuring his foot after André the Giant encouraged him to take an ill-advised ride on his personal ATV, and Guest knocking out Elwes after striking him too hard with a sword, much of the filming went by without incident.

Read any account of The Princess Bride’s production, and you’re bound to come across stories about André the Giant, who, at 7′ 4″ and over 500 pounds, drew crowds and incited strong reactions wherever he went. “Half of them run away when they see me, half of them jump into my lap,” the wrestler-turned-actor told Scheinman. Sarandon brought his two daughters to the set, who wanted to meet a real-life giant. But when confronted with André, they both screamed. It wasn’t just children, either. Robin Wright reportedly screamed and hid in her dressing room the first time she saw him; though, she warmed up to him later. “He was a smiler and never complained,” she said. Others observed that his usual response, “Yes, boss,” or “Sure, boss,” made him the most agreeable person on the set. Though, he had a lot to complain about. Stricken with a case of gigantism due to a high level of growth hormone when he was a child, André was so heavy that the weight of his body put an incredible strain on his back and neck. Along with wrestling in hundreds of matches around the world every year, the physical punishment left him to self-medicate with unbelievable amounts of alcohol, which seemed to have no visible effect on him. Even so, by all accounts, he remained genial and never reacted badly when someone reacted badly to him. Rather, he smiled and shrugged. Elwes detailed his experiences making the film in his book, As You Wish, and he devotes many pages to his friend, André the Giant, whom he wrote about with a clear admiration and humility for the wrestler’s hard life and enduring optimism.

Although the eventual film was released to positive reviews and performed moderately well at the box office, The Princess Bride, as stated, emerged as a favorite after repeat viewing on home video and television. There, fans could savor Goldman’s script, which must be one of the funniest, most quotable, and most enduring ever written. Every scene features a memorable line, each more amusing than the last. Wallace Shawn has said that he can’t walk down the street without someone yelling Vizzini’s oft-repeated “Inconceivable!” at him. And it becomes even more hilarious after Inigo’s eventual reply: “You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.” Mandy Patinkin, too, is regularly asked to recite his declaration: “Hello. My name is Inigo Montoya. You killed my father. Prepare to die.” Indeed, even amid so much sharp comedy, Goldman’s sincerity breaks through with Inigo’s stirring vow. The same is true of Westley’s tender phrase, “As you wish,” which has become a simple statement of undying devotion. But under the Man in Black’s mask, Westley is also capable of the driest sarcasm. When Fezzik inquires about his mask—“Were you burned by acid, or something like that?”—the hero’s reply is pure deadpan: “It’s just that masks are terribly comfortable. I think everyone will be wearing them in the future.” The wit even finds its way into the sword-fighting repartee, when Inigo declares, “You seem like a decent fellow. I hate to kill you.” And Westley responds, “You seem like a decent fellow. I hate to die.”

From the dialogue, it’s evident The Princess Bride contains tones—the romantic adventure, and the satire of them—that might compete in another film but find perfect harmony in Goldman and Reiner’s hands. Setting aside the humor, the film recalls the pure storybook swashbuckler akin to The Adventures of Robin Hood, complete with bright colors and a literal storybook opening when Grandpa reads to his grandson. The imagery and themes throughout register as classical, too. Westley and Buttercup seal their love with a kiss, their bodies silhouetted by the sunset. Westley goes off to find his fortune in a classical there-and-back-again journey. Buttercup’s impassioned love for Westley, Inigo’s sense of honor and duty to avenge his father, Humperdinck’s insidious plans to kill Buttercup, and Count Rugen’s chilly demeanor—they all register as genuine motivations the audience recognizes and feels without irony. Even the plot, concerning a looming war between Florin and Guilder, two fictional countries Goldman named after coins, draws from the political trappings of Swift’s adventure book. Likewise, the filmmaking adopts the look of a classical swashbuckler, seen in the matte paintings, scale models, and ageless practical effects. The film also boasts an extraordinary sword fight sequence between Inigo and Westley atop the Cliffs of Insanity, which remains one of the most impressive ever filmed. When Goldman wrote in his script that what followed was “the greatest sword fight in modern history,” Reiner set out to deliver. The sequence took months of training between Elwes and Patinkin under legendary fencers and stuntmen Bob Anderson and Peter Diamond, and it includes leaping on rocks, alternating swords between hands, light gymnastics, and expert swordplay. Captured with surprising verisimilitude, the result never looks like the work of stuntmen because it isn’t. Reiner delivered.

From the dialogue, it’s evident The Princess Bride contains tones—the romantic adventure, and the satire of them—that might compete in another film but find perfect harmony in Goldman and Reiner’s hands. Setting aside the humor, the film recalls the pure storybook swashbuckler akin to The Adventures of Robin Hood, complete with bright colors and a literal storybook opening when Grandpa reads to his grandson. The imagery and themes throughout register as classical, too. Westley and Buttercup seal their love with a kiss, their bodies silhouetted by the sunset. Westley goes off to find his fortune in a classical there-and-back-again journey. Buttercup’s impassioned love for Westley, Inigo’s sense of honor and duty to avenge his father, Humperdinck’s insidious plans to kill Buttercup, and Count Rugen’s chilly demeanor—they all register as genuine motivations the audience recognizes and feels without irony. Even the plot, concerning a looming war between Florin and Guilder, two fictional countries Goldman named after coins, draws from the political trappings of Swift’s adventure book. Likewise, the filmmaking adopts the look of a classical swashbuckler, seen in the matte paintings, scale models, and ageless practical effects. The film also boasts an extraordinary sword fight sequence between Inigo and Westley atop the Cliffs of Insanity, which remains one of the most impressive ever filmed. When Goldman wrote in his script that what followed was “the greatest sword fight in modern history,” Reiner set out to deliver. The sequence took months of training between Elwes and Patinkin under legendary fencers and stuntmen Bob Anderson and Peter Diamond, and it includes leaping on rocks, alternating swords between hands, light gymnastics, and expert swordplay. Captured with surprising verisimilitude, the result never looks like the work of stuntmen because it isn’t. Reiner delivered.

Beyond The Princess Bride’s “fencing, fighting, torture, revenge,” Grandpa explains to his bedridden listener that the story also features “giants, monsters, chases, escapes, true love, miracles.” The film fantasy supplies an antidote to video games, which had begun to replace imagination in the 1980s, as shown in the film’s opening shot of the grandson playing Hardball on his Commodore 64. Few of these fantasy elements feel kitschy or played for laughs, despite the film’s persistent humor. The Shrieking Eels look slimy and scary. In the Pit of Despair, Westley’s torture is genuinely unsettling, announced by his gut-wrenching scream. The Holocaust Cloak, however obvious the effect that replaces André the Giant with a rigid standee, makes for a convincing ruse. Even though the Battle of Wits over which glass of wine contains the iocane power features a hilarious series of logical negotiations by Vizzini, it ends in a convincing twist. And after the “mostly dead” Westley is revived and nearly regains his full corporeal composure, he confronts Humperdinck with a fight “to the pain” instead of “to the death”—and proceeds to issue an exhausting list of threats that prove amusing but also chilling. In another way, the film embraces the leaps in logic found in any storybook fantasy. Why do Westley and Buttercup fall in love? Do they have shared histories or interests? Do they have long conversations about their mutual aspirations? Is the sex great? None of the above. But their love is no less believable and a necessary component to the storybook appeal. They fall in love because that’s what classical characters in a fantasy book do.

The comedy in The Princess Bride is particularly sophisticated and sharp, capturing just the right balance. The humor never robs the narrative of its power or tips the film over into a jokefest. Compare The Princess Bride to another comedy in the storybook mold, Mel Brooks’ Robin Hood: Men in Tights, also starring Elwes. Brooks’ film looks exaggerated and stagey to match its broad humor. Elwes’ hammy delivery finds the actor looking at the camera, using over-the-top expressions, and even breaking the fourth wall—all choices ideally attuned to Brooks’ satire of The Adventures of Robin Hood’s aesthetic and Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves’ (1991) story structure. By contrast, Elwes carries a restrained smile in Reiner’s film, enough of a smirk to clue the audience into the slight parodic notes throughout but not enough to destabilize the film’s forward thrust. Leave that to Savage’s grandson character, who frequently breaks into the narrative flow by interrupting his grandpa. “Is this a kissing book?” he asks, suspicious. Falk’s character does the same, stopping when the Shrieking Eels close in on Buttercup to reassure his grandson, “She doesn’t get eaten by the eels at this time… I’m explaining to you because you look nervous.” Elsewhere, only Billy Crystal’s comic improvisations feel somewhat anachronistic, whereas Wallace Shawn’s thoroughly modern screen presence allows for brilliance in his line readings and sudden death scene.

Of course, the sheer wit of Goldman’s script is a bottomless font of inspired moments, from physical humor to dry quips (“Life is pain, your highness. Anyone who says otherwise is selling something.”) that feel immortal. In As You Wish, Elwes remarks on the film’s agelessness, despite being an ‘80s production: “Instead of a bouncy techno-pop sound track, you have the elegant slide guitar of Mark Knopfler; instead of big hair and shoulder pads, you have the period style of a swashbuckler and a princess.” With exceptions for the video game in Fred Savage’s room and the ROUSes, Elwes rhapsodizes about how the film “withstands the rigors of time,” and he compares it to the magic of The Wizard of Oz (1939) getting passed down from one generation to the next. Sure enough, the American Film Institute placed it on the “100 Passions” list of the greatest love stories, and countless other publications have ranked it among the best films ever made. Still, it’s worth wondering whether The Princess Bride would have connected with so many people, who then shared the film with their friends and families, without the help of secondary markets. But then that would require imagining a world without The Princess Bride, and who wants to think about that?

Of course, the sheer wit of Goldman’s script is a bottomless font of inspired moments, from physical humor to dry quips (“Life is pain, your highness. Anyone who says otherwise is selling something.”) that feel immortal. In As You Wish, Elwes remarks on the film’s agelessness, despite being an ‘80s production: “Instead of a bouncy techno-pop sound track, you have the elegant slide guitar of Mark Knopfler; instead of big hair and shoulder pads, you have the period style of a swashbuckler and a princess.” With exceptions for the video game in Fred Savage’s room and the ROUSes, Elwes rhapsodizes about how the film “withstands the rigors of time,” and he compares it to the magic of The Wizard of Oz (1939) getting passed down from one generation to the next. Sure enough, the American Film Institute placed it on the “100 Passions” list of the greatest love stories, and countless other publications have ranked it among the best films ever made. Still, it’s worth wondering whether The Princess Bride would have connected with so many people, who then shared the film with their friends and families, without the help of secondary markets. But then that would require imagining a world without The Princess Bride, and who wants to think about that?

Back to that poster that so disappointed Reiner and the producers, and which confused moviegoers in 1987. With its classical columns and epic landscape in the backdrop, it harkens back to traditional adventures. But with its modern-day characters reading from a storybook, it suggests the self-awareness throughout The Princess Bride, both textually and extratextually. Goldman and Reiner, along with their terrific cast of actors who disappear into their roles, created a film that works on multiple levels and greets the viewer on their terms. Storybook fantasy is not known for its subtlety; it operates in broad, unmistakable strokes. Having watched the film as a child for these swashbuckling elements and more pronounced notes, as I grew up, the film matured and revealed its comic layers. Fans everywhere continue to have similar experiences with the film, which draws everyone from grandparents to their grandchildren, from those who want a rousing adventure to those keyed into its sophisticated comedy. And though timeless is an overused word not to be used lightly, The Princess Bride meets that criterion by appealing to every age group, young and old, with the same potency today as in 1987.

(Note: This essay was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on April 5, 2023. Thanks for your continued support, Martha!)

Bibliography:

Elwes, Cary, and Joe Layden. As You Wish: Inconceivable Tales from the Making of The Princess Bride. Atria Books, 2014.

Goldman, William. The Princess Bride. 1973. 30th Anniversary Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2003.

—. Adventures in the Screen Trade: A Personal View of Hollywood and Screenwriting. Grand Central Publishing; Reissue Edition, 1989.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review