The Definitives

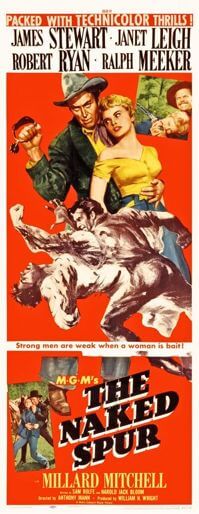

The Naked Spur (1953)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Anthony Mann’s greatest Westerns involve dark heroes who conceal their deep wounds. His heroes are extreme men at the mercy of an unseen and often irrational emotional force inside themselves. This internal hero, whose inner conflicts are distended by the natural and unforgiving landscape, pursues a villain who echoes the very worst parts of himself. Mann’s heroes appear simple and straightforward at first; their complexities are revealed gradually, while their closeness to the villain blurs the lines between good and evil. His heroes are reluctant, but in due course, they distance themselves from their initial moral ambiguity. At the same time, his villains reveal themselves to be entirely unhinged representations of what the hero might become if he does not change his ways. Over time, Mann’s heroes and villains differentiate themselves exclusively through action, and yet the director’s almost expressionist style rarely dispenses action. Mann simmers tensions until the conflict boils over into bursts of sudden, violent intensity, from which the hero survives with a measure of self-understanding. One of the few auteurs of the Western genre, Mann’s thematic and narrative structures were never more masterfully outlined in these ways than in The Naked Spur, released in 1953 at the height of the director’s talent.

Mann scholar Jeanine Basinger describes The Naked Spur’s structure as “mathematical” for its small number of characters and deceptively simple story. But simplicity barely begins to describe Mann’s skillful storytelling. The film’s minimalist structure gives way to a complex psychological cat-and-mouse game set against grand, symbolic scenery. On the western slope of the Colorado Rockies, Howie Kemp (James Stewart) hunts for a man named Ben Vandergroat (Robert Ryan), who is wanted in Abilene for killing a marshal. When Howie runs into an old prospector, Jesse Tate (Millard Mitchell), he shows Jesse the wanted poster and, assuming Howie is part of a lawful pursuit, Jesse accepts twenty dollars to join in the manhunt. When they corner Ben and a woman Lina Patch (Janet Leigh) atop a rocky cliff, a dishonorably discharged Union soldier, Lieutenant Roy Anderson (Ralph Meeker), offers to help climb up and get Ben, as Howie has failed to scale the wall himself. In time, Ben and Lina are taken into custody; Jesse and Roy join Howie to assist in transporting the prisoner back for a portion of the $5,000 bounty. But Ben, silver-tongued and scheming, pits his three captors against one another, using Lina’s femininity and their own greed against one another. For nearly the entire journey across mountainous terrain, shot on location in the Colorado Rockies, the film consists of a mere five speaking characters; only a Blackfoot Indian raiding party disturbs their solitude.

The dynamic between these characters is structured in ways that resonate with the power of high drama from the Greek masters or Shakespeare. In the alluded cruelty of Oedipus or the bloody Macbeth, violence denotes a sudden expression of emotion. Mann’s tightly wound characters build toward these expressions in ways that feel conceived by a great dramatist, the acts themselves having profound symbolic meaning for the characters onscreen and not—as in some Western filmmaking—for the sake of pure thrills. Basinger’s “mathematical” assessment of the Oscar-nominated screenplay by Sam Rolfe and Harold Jack Bloom is apt. However, perhaps geometrical is a better adjective: The sharply designed picture resembles a pentagon with character vertexes connected by lines of conflict and tragedy. This equally fixed structure blurs the usual black and white starkness between the different shapes of hero and villain, while also strengthening the connections between the main protagonist, antagonist, and the supporting characters. For all its interconnectivity, the film’s expressiveness celebrates the isolation of complex characters within a vast landscape—as though The Naked Spur was a visceral chamber drama set in the far-reaching Colorado Territory. For Mann, the wilderness landscape of the West becomes an almost ironic counterpart to the internal characters found in his Western cinema.

The dynamic between these characters is structured in ways that resonate with the power of high drama from the Greek masters or Shakespeare. In the alluded cruelty of Oedipus or the bloody Macbeth, violence denotes a sudden expression of emotion. Mann’s tightly wound characters build toward these expressions in ways that feel conceived by a great dramatist, the acts themselves having profound symbolic meaning for the characters onscreen and not—as in some Western filmmaking—for the sake of pure thrills. Basinger’s “mathematical” assessment of the Oscar-nominated screenplay by Sam Rolfe and Harold Jack Bloom is apt. However, perhaps geometrical is a better adjective: The sharply designed picture resembles a pentagon with character vertexes connected by lines of conflict and tragedy. This equally fixed structure blurs the usual black and white starkness between the different shapes of hero and villain, while also strengthening the connections between the main protagonist, antagonist, and the supporting characters. For all its interconnectivity, the film’s expressiveness celebrates the isolation of complex characters within a vast landscape—as though The Naked Spur was a visceral chamber drama set in the far-reaching Colorado Territory. For Mann, the wilderness landscape of the West becomes an almost ironic counterpart to the internal characters found in his Western cinema.

A claustrophobic thriller set in an expansive environment in which there’s no place to escape, the film develops characters in such a way that, at any moment, one individual might form an allegiance with the other, making way for several unpredictable turns and power plays throughout. Basinger called it the possibilities of “five times five.” From the outset, The Naked Spur centers on characters about which we know nothing. None of these characters are what they seem to be. Through the course of the film, each one is pushed to extremes that they might not have believed themselves capable. As a result, everyone is suspect. The seemingly kind-hearted-old-grizzly-bear-of-a-prospector is eventually revealed to be a horse-trading thief; the dishonorably discharged cavalryman is soon exposed for raping a Blackfoot princess; the criminal’s seemingly loyal woman Lina is a romantic; the chummy criminal Ben turns out to be utterly heartless. As for Howie, when he and Jesse first set off together, our hero avoids correcting Jesse—and hence the audience—when it’s intimated that he’s a lawman. Perhaps out of selfishness to keep the full bounty for himself, or maybe because this otherwise moral man feels guilt over his revenge-bent mission, Howie allows Jesse to believe capturing Ben is a noble and official quest until he’s revealed by Ben to be a bounty hunter.

The Naked Spur marks the third in Mann’s handful of collaborations with screen legend James Stewart between 1950 and 1955, an actor-director partnership rivaling Wayne-Ford, De Niro-Scorsese, or Mifune-Kurosawa. Having earned a reputation as a fresh-faced star of romantic comedies and cheerful Frank Capra pictures in the 1930s, Stewart returned from his service in World War II and, in time, gave his onscreen persona a drastic facelift. Except in his collaborations with Alfred Hitchcock, particularly Vertigo (1958), Stewart never played characters more complicated than in the Westerns he made with Anthony Mann. Their partnership began in 1950 with Winchester ’73, continued in Bend of the River (1952), reached a height with The Naked Spur, and lasted through the exceptional The Far Country (1954) and The Man from Laramie (1955). Under Mann, Stewart played characters who only find their humanity after losing themselves in a very private world of their own passions. Far removed from any sense of community, Stewart’s heroes find themselves alone in the wilderness, their dramatic crises propelling them further into isolation and disorder. After a violent struggle, they finally surface, once again whole. Stewart was perfect for Mann. The actor’s screen presence was defined by his all-American charm, yet under his exterior, he could unleash disturbing heights of emotion.

The Naked Spur marks the third in Mann’s handful of collaborations with screen legend James Stewart between 1950 and 1955, an actor-director partnership rivaling Wayne-Ford, De Niro-Scorsese, or Mifune-Kurosawa. Having earned a reputation as a fresh-faced star of romantic comedies and cheerful Frank Capra pictures in the 1930s, Stewart returned from his service in World War II and, in time, gave his onscreen persona a drastic facelift. Except in his collaborations with Alfred Hitchcock, particularly Vertigo (1958), Stewart never played characters more complicated than in the Westerns he made with Anthony Mann. Their partnership began in 1950 with Winchester ’73, continued in Bend of the River (1952), reached a height with The Naked Spur, and lasted through the exceptional The Far Country (1954) and The Man from Laramie (1955). Under Mann, Stewart played characters who only find their humanity after losing themselves in a very private world of their own passions. Far removed from any sense of community, Stewart’s heroes find themselves alone in the wilderness, their dramatic crises propelling them further into isolation and disorder. After a violent struggle, they finally surface, once again whole. Stewart was perfect for Mann. The actor’s screen presence was defined by his all-American charm, yet under his exterior, he could unleash disturbing heights of emotion.

As The Naked Spur progresses, we learn during Howie’s fever dream rant that his former fiancée, Mary, sold his farm when he went off to fight in the Civil War. Howie wants Ben’s bounty to buy back his land and restore his dignity; his anger is directed inward more than outward. He lashes out because he was shown to be vulnerable—a bad thing to be in the West. Stewart’s performance steadily transforms from a hero into a tortured anti-hero as Howie’s psychological dilemma manifests itself in physical forms: He’s incapable of climbing the rock face in the opening and needs Roy to climb for him. When trying to save Lina from a Blackfoot raid, Howie takes a bullet in the leg; for the remainder of the picture, he walks with a limp, at one point falling with exhaustion from his horse. Never in the picture does Howie get it easy. Stewart’s tortured face remains full of desperation and twisted emotion, while the actor’s affable onscreen persona maintains our sympathy for the character. It’s during the Blackfoot raid that we begin to see Howie as caught somewhere between good and evil, his borderline psychopathic obsession to recover from the blow to his ego pushing him to manic extremes. When he runs out of bullets during the raid, he beats one native to death with his gun; another he stabs several times beyond what would be needed to end a life. Afterward, as they leave the site of the raid, Howie hangs his head and stops to look at the body of the Indian he has killed. That night, he’s plagued by nightmares from which he awakens with frenzied, delirious dreams of Mary and his family still on his tongue. All the time, we question if Howie will resort to murder to get his farm back. With someone like Ryan’s Ben Vandergroat egging him on, it’s shocking he doesn’t.

Ben is the kind of villain Mann delights portraying. At first, he’s more likable than anyone else onscreen, certainly more than Stewart’s rage-fuelled bounty hunter. His sad backstory about the father who beat him and the mother who died of fever almost draws our sympathy. Everyone onscreen is at the mercy of his ever-running mouth, which spouts out each remark with an ironic chuckle and knowing smile behind it. His every word is intended to make his captors consider their position and rethink their loyalties to one another. When he suggests to his three escorts, “Money splits better two ways than three,” he exploits the worst in each man, planting seeds of deception. He’s even a pseudo-philosopher whose motto “Choosin’ a way to die, what’s the difference? Choosin’ a way to live—that’s the hard part” is practiced in his calculating and charming demeanor. The world is a joke to him, so is death. And so, Ben is a master manipulator. He only opens his mouth when the words serve a purpose, and trusting him becomes a grave mistake for at least one member of this posse. As the story progresses, he uses Lina to bring out the unscrupulous lust of the cavalryman and appeal to the broken-hearted romanticism of the vengeful former farm owner. All the while, he controls Lina by getting her to rub his shoulders with his customary and suggestive command: “Do me.” He might even win us over with his now-grown misguided youth routine if he weren’t so absolutely evil and devoid of human sympathy. Lina finally realizes this when she witnesses Ben on high shooting down at the feet of Jesse’s corpse and laughing about it.

Ben is the kind of villain Mann delights portraying. At first, he’s more likable than anyone else onscreen, certainly more than Stewart’s rage-fuelled bounty hunter. His sad backstory about the father who beat him and the mother who died of fever almost draws our sympathy. Everyone onscreen is at the mercy of his ever-running mouth, which spouts out each remark with an ironic chuckle and knowing smile behind it. His every word is intended to make his captors consider their position and rethink their loyalties to one another. When he suggests to his three escorts, “Money splits better two ways than three,” he exploits the worst in each man, planting seeds of deception. He’s even a pseudo-philosopher whose motto “Choosin’ a way to die, what’s the difference? Choosin’ a way to live—that’s the hard part” is practiced in his calculating and charming demeanor. The world is a joke to him, so is death. And so, Ben is a master manipulator. He only opens his mouth when the words serve a purpose, and trusting him becomes a grave mistake for at least one member of this posse. As the story progresses, he uses Lina to bring out the unscrupulous lust of the cavalryman and appeal to the broken-hearted romanticism of the vengeful former farm owner. All the while, he controls Lina by getting her to rub his shoulders with his customary and suggestive command: “Do me.” He might even win us over with his now-grown misguided youth routine if he weren’t so absolutely evil and devoid of human sympathy. Lina finally realizes this when she witnesses Ben on high shooting down at the feet of Jesse’s corpse and laughing about it.

With every line out of Ben’s mouth playing to his advantage, the dimmer Jesse and Roy never have a chance. Their roles, though secondary, are crucial to building the vital tension between Howie and Ben. They aggravate Howie as a necessary evil—he needs them to transport Ben back to Abilene safely—but they are also witnesses. Through them, Howie must consider his conscience and the moral implications of his actions. Had Howie found Ben all alone, there would have been little reason not just to shoot him dead (after all, the wanted poster says “dead or alive”). For Ben, Jesse and Roy supply an opportunity for error, part of the flawed human condition that Ben knows just how to exploit to his advantage. Jesse is likable and perhaps even gentle, his death necessary to demonstrate Ben’s cruelty. With Lina terrified as Ben shoots at Jesse’s feet, Ben remarks with a chuckle: “Day after tomorrow, it’ll be just like a story you once heard.” Roy, however, represents the cruel nature of a Man of the West; his discharge notice even references his “morally unstable” temperament. If Howie chooses to murder Ben outright, his morality will take a nosedive into a “morally unstable” gorge alongside Roy.

Howie’s desperate need to claim the bounty on Ben’s head subsides one evening, albeit fleetingly, when the group takes shelter in a cave, where Howie and Lina fall in love. Here we see Howie’s otherwise absent humanity unearthed, and Lina’s budding sympathies for the hero grow into genuine affection. Howie, Jesse, and Roy agree to take shifts sleeping, and the former takes the first shift. Lina approaches Howie on Ben’s order, which will allow Ben to slip away as she provides a distraction. She strikes up a conversation as Howie sits at the edge of the cave, listening to rain droplets falling into cups and dinner pans. Howie quips that Roy’s pan sounds off-key. They both laugh, and the tension of the film thus far fades away for a brief moment. The on-location photography present throughout the rest of the production transforms now into a Hollywood set, designed to frame Howie and Lina’s intimacy in the glow of the firelight. Lina, having heard Howie’s tirade about his heartbreaking past during his fever dream, has already begun to show compassion for him. And in this gentle scene, Lina falls in love with Howie, while Howie lets his guard down as the two share their mutual desire for land, a farm, and a family together. More than just a device of temptation for the rapist Roy or a lingering distraction for Howie, Lina signifies Howie’s second chance at rebuilding his life. More than the presence of Jesse or Roy, Lina provides a moral compass for Howie by embodying the potential for a normal life, and in that, she reminds Howie how he’s lost himself in his current mission.

Howie’s desperate need to claim the bounty on Ben’s head subsides one evening, albeit fleetingly, when the group takes shelter in a cave, where Howie and Lina fall in love. Here we see Howie’s otherwise absent humanity unearthed, and Lina’s budding sympathies for the hero grow into genuine affection. Howie, Jesse, and Roy agree to take shifts sleeping, and the former takes the first shift. Lina approaches Howie on Ben’s order, which will allow Ben to slip away as she provides a distraction. She strikes up a conversation as Howie sits at the edge of the cave, listening to rain droplets falling into cups and dinner pans. Howie quips that Roy’s pan sounds off-key. They both laugh, and the tension of the film thus far fades away for a brief moment. The on-location photography present throughout the rest of the production transforms now into a Hollywood set, designed to frame Howie and Lina’s intimacy in the glow of the firelight. Lina, having heard Howie’s tirade about his heartbreaking past during his fever dream, has already begun to show compassion for him. And in this gentle scene, Lina falls in love with Howie, while Howie lets his guard down as the two share their mutual desire for land, a farm, and a family together. More than just a device of temptation for the rapist Roy or a lingering distraction for Howie, Lina signifies Howie’s second chance at rebuilding his life. More than the presence of Jesse or Roy, Lina provides a moral compass for Howie by embodying the potential for a normal life, and in that, she reminds Howie how he’s lost himself in his current mission.

Nevertheless, Mann transforms the cave’s romantic environment into a claustrophobic cell wherein each character must confront the others’ true, terrible nature, and each of their carefully assigned dynamics come to a head. Just as Howie embraces Lina in a kiss, Ben uses the distraction to crawl away and cause a small cave-in, and then attempts to inch through the cave’s narrow rear exit. When the others catch Ben, Howie all but begs for a reason to kill him. He even stuffs a gun down the front of Ben’s pants and tells him to draw. Roy cuts Ben’s hands loose to make it a “fair fight.” Jesse stands ready with a shotgun, primed to kill. Roy calls for Howie to take the shot. Lina watches, terrified. Confident and even mocking of Howie’s morality, Ben lowers his hands and says he will not draw. “If you’re going to murder me, Howie,” he says, smiling, “don’t make it look like something else.” Howie would never kill in cold blood, nor even in an unfair duel. Roy goes for the gun to kill Ben himself, but Howie and Jesse stop him. They’re not murderers. Shotgun in hand, Jesse remarks, “It’s gettin’ so I don’t know which way to point this no more.” Now Roy accuses Howie of making a deal with Lina to keep Ben alive, and Howie lashes out at Lina, suggesting their warm moment together was planned. When they leave the cave, each character is even more alienated than when The Naked Spur began. Perhaps this is why Ben can convince Jesse, the old prospector, to ditch Howie and Roy for a chance at a gold mine. All too trusting, Jesse leads Ben and Lina away from the camp one night, but Ben soon turns on his new partner and shoots him in cold blood. Lina, shocked at Ben’s callousness, finds herself dragged to a high rock face above some whitewater rapids. There they wait to ambush Howie and Roy.

From the opening’s rocky wall to the cave sequence, and finally, to the rapids, Mann’s wilderness mountains, forests, and raging rivers reflect the passions and conflicts of his heroes and villains. The peaceful scenery is interrupted by the violent actions between men. In the climax, Howie and Roy approach Ben and Lina’s position. Roy lays down covering fire as Howie maneuvers around the rock face. Although he was incapable of climbing the wall in the opening scenes, he’s come far throughout the film and now makes the climb, using one of his spurs as a makeshift climbing pick. Throughout the film, an evil inside Howie has driven him on this desperate quest, while the good in him prevents him from carrying out his worst impulses. Now, this rage has blinded him, and he’s ready to kill. In the first scenes, he’s unable to climb the rocks after Ben and hasn’t thought out his plan to transport his bounty—he needs Jesse and Roy. By the end, Howie’s mission has become clearer, his rage greater even than when his mission began, especially after seeing that Ben has killed Jesse. He climbs up himself without the benefit of others, the rapids roaring below him. Caught between two deadly forces—Ben and the river—he pulls himself up, and when he reaches the top, he tosses the naked spur into Ben’s face.

From the opening’s rocky wall to the cave sequence, and finally, to the rapids, Mann’s wilderness mountains, forests, and raging rivers reflect the passions and conflicts of his heroes and villains. The peaceful scenery is interrupted by the violent actions between men. In the climax, Howie and Roy approach Ben and Lina’s position. Roy lays down covering fire as Howie maneuvers around the rock face. Although he was incapable of climbing the wall in the opening scenes, he’s come far throughout the film and now makes the climb, using one of his spurs as a makeshift climbing pick. Throughout the film, an evil inside Howie has driven him on this desperate quest, while the good in him prevents him from carrying out his worst impulses. Now, this rage has blinded him, and he’s ready to kill. In the first scenes, he’s unable to climb the rocks after Ben and hasn’t thought out his plan to transport his bounty—he needs Jesse and Roy. By the end, Howie’s mission has become clearer, his rage greater even than when his mission began, especially after seeing that Ben has killed Jesse. He climbs up himself without the benefit of others, the rapids roaring below him. Caught between two deadly forces—Ben and the river—he pulls himself up, and when he reaches the top, he tosses the naked spur into Ben’s face.

The psychological motivations in both Rolfe and Bloom’s script and William Mellor’s gorgeous Technicolor cinematography play out beautifully during the climax. When Howie throws the spur, Ben screams out in pain, while from behind, Roy fires into Ben’s back and sends him falling into the rapids below, where the river carries him into a small alcove. Roy lassos a rope across the rapids, and when he reaches Ben’s corpse, he ties the rope around it. Howie takes the other end. All at once, the rushing waters float a log downstream that slams Roy into oblivion. With Lina screaming “Ain’t that enough!” our hero reaches a hysterical height, pulling Ben’s body upstream. Lina begs Howie to cut the body loose, but he shouts, “I’m takin’ him back. This is what I came after, and now I got it. He’s gonna pay for my land.” But both Lina and Howie know that he’ll never be able to move on if he buys his farm back with blood money. Still, Howie rants on as he pulls the body ashore and drags it back to his horse. “The money—that’s all I care about. That’s all I’ve ever cared about. Maybe I don’t fit your ideas of me, but that’s the way I am.” Lina resignedly says she’ll follow Howie no matter what he wants, and the guilt over her selfless decision sends Howie into a breakdown. Defeated from the ordeal and finally absolved of his hatred by Lina’s love, Howie buries Ben and, in that act, frees himself of his obsession with a willingness to start over. Lina and Howie ride off together, the past dispelled and the future hopeful.

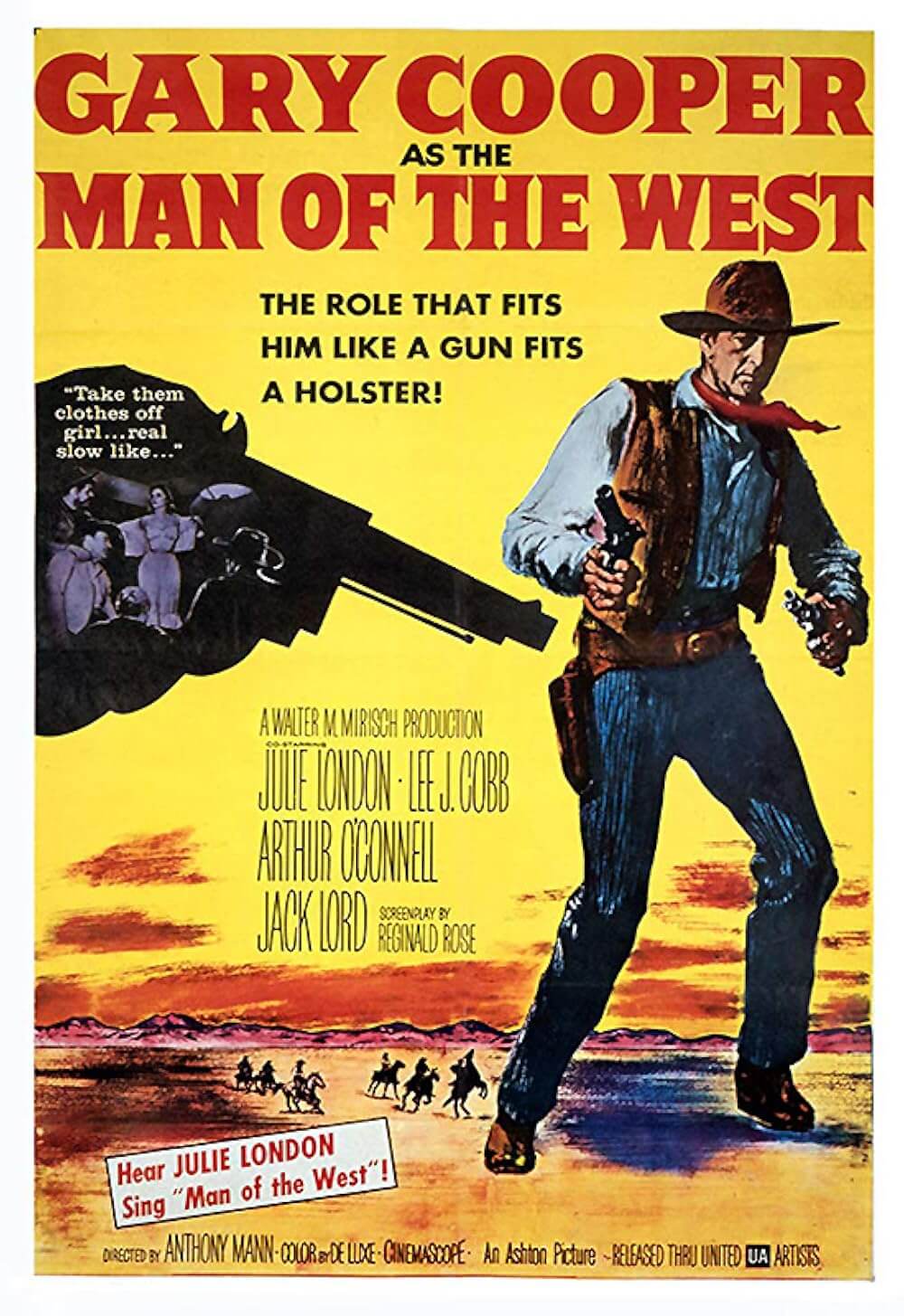

In her critical biography and study of Mann as an auteur, Basinger put it best when she wrote, “Anthony Mann’s films are about journeys undertaken by a hero in which he crosses a landscape and emerges with a new understanding of himself.” This was true whether Mann was directing a pulpy film noir yarn or one of his later Hollywood epics, but never more precise or celebrated than in his Westerns. More in-depth than any other Western filmmaker, even John Ford (The Searchers, 1956), Mann explores the human element of the West with a visceral edge that has more in common with the Westerns of Samuel Fuller (I Shot Jesse James, 1949) or Nicholas Ray (Johnny Guitar, 1954). Ford mainly examined the West’s history and myth-making as it relates to American identity, whereas Mann populates the landscape with dark heroes, savage emotion, and high drama. Like iconic stage plays and classical storytelling, his cinema achieves a pinnacle in art-as-entertainment from which a profound self-understanding materializes out of violence and tragedy. The Naked Spur joins Mann’s other dynamic Western masterpieces, such as The Furies (1950) and Man of the West (1958), as one of the genre’s most exciting and sophisticated offerings. From the beset Howie Kemp to the uncaring Ben Vandergroat and everyone in between, Mann explores the high and low limitations of humankind and, through them, constructs an unforgettable Western.

Bibliography:

Basinger, Jeanine. Anthony Mann. New and Expanded Edition. Middletown: Wesleyan, 2007.

Kitses, Jim. Horizons West: Directing the Western from John Ford to Clint Eastwood. British Film Institute; 2Rev Ed edition, 2008.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review