The Definitives

The Music Room (1958)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

In The Music Room, Satyajit Ray looks back at the relationship between a patrician class and their music, which was about to vanish from Indian culture in the post-independence drive toward modernization. A tradition sustained by patriarchal nobility in private rooms reserved for music and dance, the jalsaghar or music room was a place of upper-class exclusivity, where the privileged few gathered in a mutual appreciation and patronage of musical artists. Many of India’s most renowned dancers, composers, and performers from the pre-modern age made their legacy in such rooms. By the time Ray released the film in 1958, these privately held showcases of voyeurism and artistic admiration had all but disappeared. The tradition of listening to classical music had since been shifted from private music rooms into the popular public space of the commercial films of Bombay (now Mumbai), where music and dance were accompanied by distractions such as narrative and cinematic form. The purity of classical music was being forgotten. By telling a story that brought this era to the screen, Ray at once mourns the loss of such spaces while underscoring the downfalls of the past. Indeed, Ray maintained an interest in the singularity of human lives in their particular world throughout his career. He did so not in an attempt to universalize the human experience as a familiar occurrence for all; rather, as The Music Room demonstrates, he explored individuals, their stories and cultural reality, with an uncommon measure of empathy for their uniqueness.

Ray approaches the subject of The Music Room with all its cultural specificity intact, albeit in such a way that feels familiar and relatable to viewers across the globe who are otherwise unfamiliar with the specifics of Bengali culture. Many Western viewers too easily interpret the relatability of Ray’s films and characters as a sign of his enduring universality as a storyteller, which conveniently denies the cultural uniqueness of his perspective and the Bengali culture in which a film like The Music Room takes place. Instead, understandably so, Western audiences focus on concepts and emotions to which they can personally connect. Explorations of the social textures in Ray’s work, despite attempts at understanding Ray’s distinct perspective within Indian culture, have given way to dismissive claims that Ray operates as a universal filmmaker. But The Music Room demands consideration of its author and textuality to understand the cultural specificity at work. The film unfolds in a particular time and place that distinguishes Ray’s characters as culturally unique. They are not, as many have argued, universal in their creation. Instead, much of their familiarity comes from their recognizable Western influences, born from imperialist seizure, whereas the unfamiliar qualities, unique to Bengali culture, demand investigation.

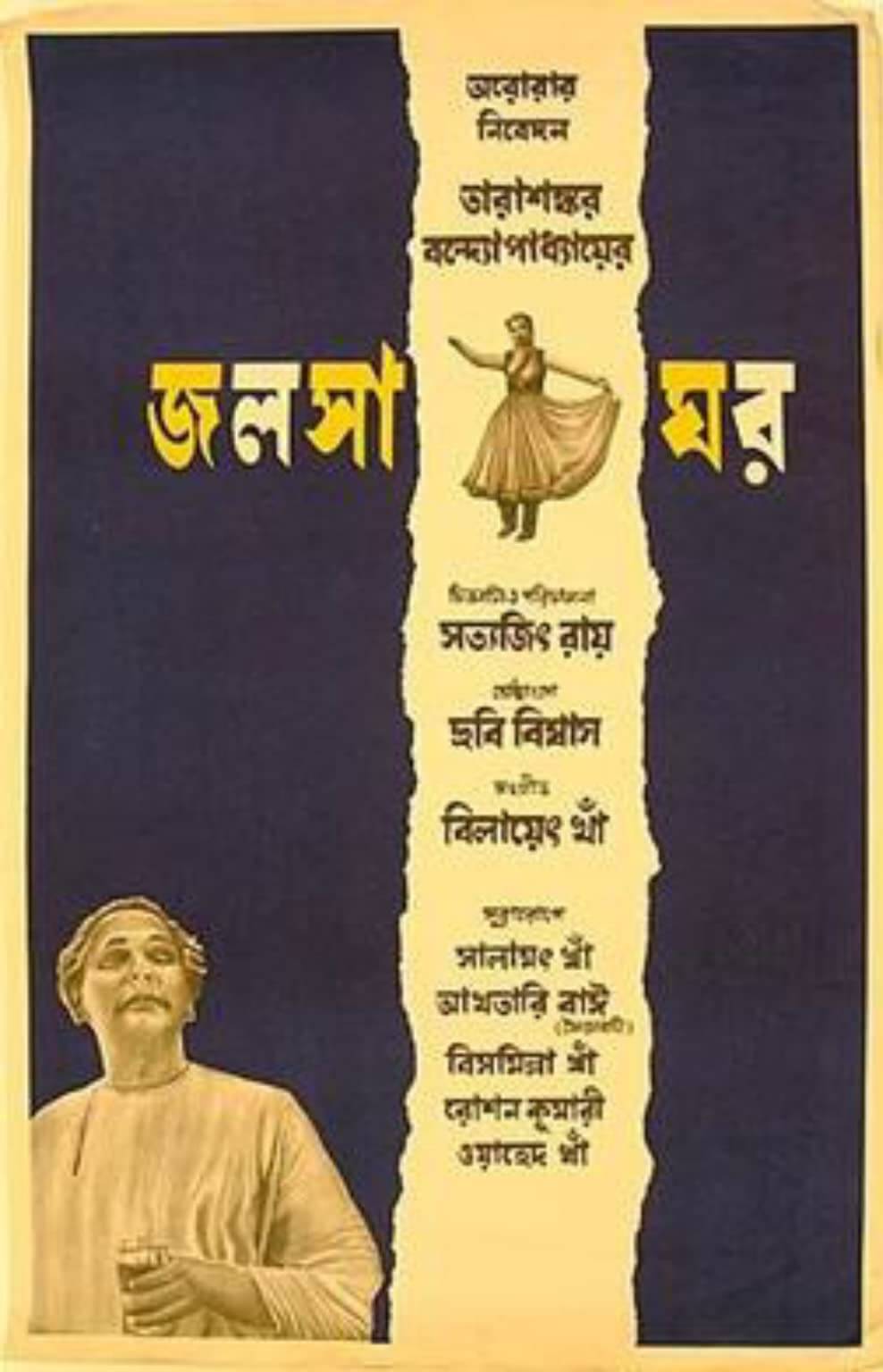

Made to ensure himself a hit after the failure of Aparajito (The Unvanquished, 1956), the second entry in his Apu Trilogy, Ray’s screenplay for The Music Room was based on a short story by Tarashankar Banerjee, one of the most celebrated authors in India. Bengali audiences would immediately recognize the material. Set in a feudalistic, aristocratic era at the turn of the twentieth century, the plot follows Biswambhar Roy, played by Chhabi Biswas, an aging zamindar (landowner) who jealously clings to his self-importance. He’s representative of an archaic worldview that has gradually transitioned out of fashion. In a ragged estate in rural Bengal that signifies Roy’s once decadent lifestyle, Roy refuses to adapt to the trend of urbanized Indians of the modern world. That stubbornness, fueled by his passion for the music performed in his jalsaghar, and the pride such performances bring his status as gentry, becomes his undoing. At the same time, Roy’s melancholic and solitary existence in the shabby surroundings is not undeserving of the audience’s sympathy. The increasingly capitalistic priorities of the modern age may have obliterated the claims to authority granted to him by birthright and lineage, but there’s an undeniable fascination for the high degree of appreciation and patronage for music and dance unique to this period.

By the film’s release in 1958, the majority of the Indian public had little experience with classical music presentations such as those depicted in The Music Room. The nobility had exclusive access to music rooms. Although music played a major role in the everyday lives of the Indian public, their access to this sort of music was limited. Ray himself noted, “the cinema is the only form of available inexpensive entertainment. They have not the choice that the western public has of music halls, revues, plays, concerts, and even, sometimes, of a permanent circus. Yet the craving for spectacle […] remains and has somehow to be met.” While Ray used The Music Room to supply his audience with a fulfillment of their craving, he nevertheless insists upon critiquing the feudalistic world in which it takes place. Ray’s critique of his character, while simultaneously feeling for him, results in a film about a man so devoted to traditions that he refuses to change. Through Roy’s story, Ray resolves that an unwillingness to change assures the ruination of any human being. But to fully appreciate the themes and connections between this history and the cultural environment requires some awareness of the types of classical music being played—or at least how their usage in the film, blended at times with modern musical notes, represents Ray’s sadness over the loss of such music performances and his concurrent belief in the necessity of the era’s passing.

The Music Room was filmed at the palace of the Chowdhurys at Nimtita, which contained everything the shoot needed except the titular music room; the palace’s jalsaghar proved too small, requiring set designer Bansi Chandragupta to create one. Chandragupta installed the elaborate chandelier in the room’s center and brought in mirrors to impart the illusion of a larger space. For the music, Ray hired composer Vilayat Khan, who had worked for a patron not unlike Biswambhar Roy, and his music treats the film’s subject as tragic and empathetic, rather than the more cutting criticism of feudalism that Ray sought. Khan’s music combined classical ragas (melodic frames within Indian music) and a contemporary film score more appropriate for cinema, a distinction lost on many Western viewers. Ray cast well-known singers and dancers to ensure memorable presentations in Roy’s jalsaghar, which are mesmerizing for their sheer beauty and skill: Begum Akhtar made her final film appearance to sing in the thumri genre to which she was versed; Salamat Ali Khan sang in the improvisational kheyal style; and the famed Roshan Kumari, a celebrated dancer and choreographer, gives a hypnotic performance as a Kathak dancer. The jalsas (concerts) in the film combine Khan’s Eastern and Western sounds in a way that proved unconventional to many Indian viewers, evoking the blend of historical setting and progressive ideology that reflected Ray’s perspective.

The rich details of Ray’s production mark an obvious appreciation for a specific cultural past, while his use of form demands contemplation. Consider how Ray evokes the past and present by setting a temporal mood, incorporating a perceivable slowness to his work that evokes a ponderous nature, indicative of reflection and a consideration of time. The performance by Biswas has a similar quality, given how he seems to be in a trance for much of his screentime, gloomy and still, as if he were irremovably connected to his crumbling palace. And then there’s the film’s tableau-like construction, whereby Ray structures his film around the jalsas, which seem to take prominence over the narrative’s deeply tragic events. To be sure, viewers of The Music Room are bound to feel more from the brilliance of the musical showcases, each revealed in long sequences that alternate shots between the performers in their virtuoso presentation, and the admiring audience that appears entranced by the display of musical artistry. In this way, music transcends an accompaniment to a given scene and elevates itself into an expressive drama unfolding before both the spectators onscreen and the film’s viewer.

Roy’s almost ghostly, rapt devotion to these hypnotic performances in his music room is contrasted by Ray’s characterization of the modern personality, Roy’s young businessman neighbor, an upstart named Ganguli (Gangapada Basu). Whereas Ganguli tries to impress the nobleman with his money and modern conveniences, he has none of the time-honored tact or devotion to etiquette as Roy. Through Ganguli’s portrayal as a disrespectful member of a newer generation, Ray demonstrates his respect of the zamindars’ patronage of the arts, and recognizes that, without them, music would not have been so ingrained into the larger culture. However, the narrative’s trajectory acknowledges the director’s belief that a devotion to the past results in the destruction of progress. Every time Roy dusts out his shrouded music room for another performance to satisfy his love of music, an act that strokes his ego and status just the same, he engages in an act of self-destruction. He spends the last of the estate’s reserves, which he cannot afford to do, or pawns his wife’s jewels to host another performance. One crucial jasla in the film, hastily assembled by Roy in the midst of a dangerous storm, satiates the nobleman’s desire, to the extent that he demands the return of his wife and son, who have traveled to see her family, so they too can bask in his grandeur. However outstanding the performance, Roy’s family is lost during the storm, having drowned in the nearby Padma River during their rushed homecoming.

Much like his theme in The Big City (1963), Ray shows time-honored traditions being upended by newer, but not necessarily better ways of thinking. He respects tradition, but at the same time, he supports the necessity for growth through development. Ray did not buy into the developmental myth, that with change comes improvement; it was simply something different, on its way to becoming better. Commitment to progress is what remains important. Given the filmmaker’s appreciation for the past, Roy is not the unsympathetic character he might have been. “He’s pathetic, like a dinosaur that doesn’t realize why it’s being wiped out,” said Ray, aware of the sadness and tragedy inherent to a creature that will soon die. Observe the final scenes, in which Roy spends every last penny on a final jasla in a show intended to demonstrate his superior class to Ganguli. After this last gesture of his aristocratic standing, Roy, languid and forlorn, wanders his estate, until he convinces himself to take a final ride on the beach on one of his horses. Riding on the beach of the Padma, past the very boat that sunk with his wife and child inside, Roy falls from the stallion to his death. With this sequence, Ray’s readiness to eulogize what Roy represents does not result in glorification; alternatively, he remains open enough to affirm that Indian culture owes a debt to traditions, even while he condemns the ego of the class systems from which that culture derives.

The emotions achieved at the end of The Music Room are more complicated than the simple catharsis achieved by either Hollywood or Mumbai commercial films. They demand a consideration of history, culture, and art—and the transitory nature of these phenomena. As a result of his concentration on humanist drives, it’s not surprising that Ray remains the most well-known Indian director outside of India, despite achieving only modest commercial success during his lifetime in both his country and abroad. In many ways, he remains more popular in non-Indian countries than his homeland. Historians, critics, and biographers explain this by describing Ray’s work through its universality, often calling his films boundlessly humanistic—a quality that transcends any cultural specificity and finds only the commonalities among them. But Ray’s films were neither jealously Indian nor striving for a universality that would better introduce non-Indian viewers to his culture. Although it is tempting to characterize Ray’s films in such ways, his identity as a filmmaker both embraces and defies any singular cultural association or perceived universality. Upon closer examination of his life and work, Ray can be seen as a distinct auteuristic identity who has been one-dimensionally described with the reductive label of universal, while conversely, Ray remains distinguished by his postcolonial humanist compassion and a myriad of distinct cultural influences on his identity as a filmmaker.

Ray’s particular artistic and postcolonial identity as a New Indian Cinema filmmaker has roots that go deeper than the emergence of Indian cinema; they go several generations back in history. European culture shaped Indian society along with the more predominant influences of Hinduism and Islam. The British Empire’s East India Company had traded in India since the 1600s, but by the end of the seventeenth century, India represented a central trading destination for the West. By the mid-1850s, the British had overcome Portuguese and French competition in the region, and their government transformed India into a colony, with Calcutta (now Kolkata) as the capital of the British Empire in India. The presence of English influences on Bengal led to a cultural expansion, and a Bengali Renaissance formed around a sudden cosmopolitanism and against British officialdom, requiring a new Indian middle class to fulfill civil-service roles. Within this Bengali Renaissance, the Brahmo Samaj formed in the 1820s from a group of English-speaking Indian elites, headed by Ram Mohan Roy. The Brahmos adopted new European ideas and applied them to Indian society, with democracy, feminism, and social justice among them, drawing from Christianity and Western literature to create a reform movement of the Hindu religion that sought to update Hindi society through a monotheistic form. Even so, many Brahmos considered themselves neither Hindi nor Christian. The Ray family maintained a position of influence during the Bengal Renaissance; even the surname Ray, derived from “Raja,” was an honorable title given to families that had elevated themselves up through the social ladder.

Further biographical insight is available in how he lived his life, how he studied, and how he developed his artistry—all of which prove distinct in any culture, including his own. His heritage in a family of Indian artists and creatives that were opposed to British rule, his coming of age amid the emergence of Indian independence, as well as his role in a new Bengali liberalism amid the Brahmos, shaped his bifurcated outlook. His education in both Indian and Western forms of painting, classical music, and filmmaking—especially his time at the University of Santiniketan under the great Rabindranath Tagore—gave him broad insights into his own aesthetic desires. As a director, Ray admitted that European and Hollywood filmmakers influenced his work more than those from the popular Bombay studio system, lending his films visual and narrative structures that seem familiar to Western viewers. Regardless of the vast potential for the attribution of influences, simply picking one over another is too narrow an interpretation. Ray’s auteurist identity is not wholly Indian, Western, or even universal, but his own. Moreover, by arguing against Ray’s generalized universality, as such descriptors are an oversimplification, this essay does not ignore that the director’s films are beloved across the globe, which would seem to present a staggering counterpoint.

Audiences and writers have labeled Ray’s filmmaking as universal since his 1955 debut Pather Panchali, the first entry in his Apu Trilogy, which was awarded Best Human Document at the 1956 Cannes Film Festival. As Ray continued making films, writers continued to describe the universal appeal of his work. In his book Theory of Film, Siegfried Kracauer described Aparajito by writing, “You see this story happening in a remote land and see these faces with their exotic beauty and still feel that the same thing is happening every day somewhere in Manhattan or Brooklyn or the Bronx.” John Flaus notes Ray’s ability to capture “the unspoiled sense of affinity with all the human species, the acceptance of human limitations, the rejoicing in the human capacities.” Flaus argued that while entrenched in the signifiers and minutiae of Bengali society, its customs, its traditions, and its transition from a colonized to a postcolonial country, Ray’s films chart how “from the accidents of culture emerge the constants of humanity.” By contrast, others have described Ray as quintessentially Indian. Ray’s biographer Andrew Robinson described his films as having “encompassed a whole culture.” Robinson also wrote, “Ray’s is the art that conceals art,” suggesting the director’s body of work artfully expressed Indian culture without revealing an obvious intention to do so. But contrary to Robinson’s claim, scholar Keya Ganguly argues that describing Ray’s body of work as either characteristically Indian or universal “reinforces the West’s normative claims while locking the non-West into relativisms about the particular and the primitive.”

Given the blend of Eastern and Western influences on Ray resulting from British colonialism, many critics in the West have characterized Ray’s approach as that of an Englishman born from imperialism, thereby denying the Indian specificity of Ray’s culture. Such cultural appropriation was not uncommon for critics ranging from Bosley Crowther to Roger Ebert. In his review for The Big City, Ebert wrote, “Satyajit Ray of India understands us better than Jerry Lewis.” Remarks such as this serve several purposes. They seek to convince moviegoers in the U.S. that a film from India is worth seeing because its themes are relatable. They also characterize Indian cinema in relation to the West, as if Ray is specifically speaking to the West. Lastly, they deny Ray’s films of their uniqueness of identity, focusing on what is relatable to the Western viewer and ignoring the qualities unique to Indian culture. Perhaps this is why critics and scholars concentrate on a supposed dialectic between Ray’s Westernized artistic sensibilities and the distinctly Indian “rambling, open-ended narratives that he adapts,” according to scholar Roy Armes. But instead of asking whether Ray’s cinema is of more Eastern or Western influence, those examining his work should investigate what it is.

In a 1974 interview, more than 20 years after taking notes from Ray on his India-set film The River, director Jean Renoir told critic Penelope Gilliatt, “Ray is quite alone, of course.” Renoir meant that Ray, as a pure artist working in the cinematic medium, had few contemporaries who had not sold their artistry to Hollywood and made artistic compromises along the way—Renoir included. For most of his career, Ray retained his artistic autonomy and creative control, telling stories that interested him and working with a series of regular collaborators. Ray later admitted that his middle-class upbringing did not produce enough life experience to imagine stories from every walk of life, and he often relied on source material. Having directed 32 feature-length films, two-thirds of them originate from preexisting source material, including several stories penned by Tagore or Banerjee. Early in his career, he worked with composers such as Ravi Shankar, Vilayat Phan, Ali Akbar Khan, and Jyotirindra Moitra. But as the most talented Indian composers were drawn to the Mumbai film industry—and he often had meticulously detailed notes for his composers anyway, which often caused conflicts—he resolved to maintain control over his scores by learning several instruments. Ray composed most of the music in his films after Three Daughters (1961), sometimes in a Western style, sometimes in a distinctly Indian style, but more often in a fusion of East and West. Indeed, Ray’s approach to filmmaking, in general, is often described as a mixture of influences.

Ray’s films are not dissimilar from his writings as a film critic, published in the anthologies Our Films Their Films (1976) and On Cinema (1982). In one of Ray’s reviews, he might refer to Italian master Vittorio De Sica next to Soviet director Mark Donskoy and then, in the same review, reference Rabindranath Tagore. In the same way, he draws from a multitude of influences as a filmmaker, and those influences are not exclusively Eastern or Western; rather, they are singular for their refraction through Ray’s specific artistic lens. “Filmmaking is a democratic undertaking, I think,” he told his biographer, and that philosophy suggests his independence and self-governing as the director, writer, producer, and composer of most of his films, as opposed to any overarching adherence to a national style. Ray’s work does not adopt the influence and awareness of international filmmakers to affect a universal appeal. His own films, The Music Room included, contain countless details and nuances that prove untranslatable to audiences unfamiliar with the intricacies of Indian family dynamics or social structures.

Aspects of Ray’s films can be seen to adopt Western characteristics. His approach to narrative, for example, reflects Western precepts, as his structure and economy of plotting reflect classic Hollywood’s philosophy of form-follows-function. Unlike Bollywood titles that contain plot piled atop plot, Ray’s films have three-act structures and a temporal efficiency derived from the influence of Hollywood craft. He incorporates time-images and narrative-images that reflect classical Hollywood’s concentration on the shot-for-shot logic, echoing Western concepts of time into his films. By contrast, the average Indian film lacks temporal logic between periods of time, often characterized by the predominance of loose narrative structures and the longwinded, divergent style of Mumbai cinema. To be sure, Ray’s films stand as the inverse of many Indian films, and what Robinson calls their “impact of the cynical materialism that masquerades as liberation over all the world today, and perhaps especially in today’s India.” Ray’s cinema is more decisive, organized, intentional, and sensitive.

Though Ray’s style does not derive from Indian cinema—with its origins in stagecraft and mythological adaptations—and certainly not from the popular Mumbai style of Bollywood, some characteristic Indian forms of expression appear in Ray’s work. For instance, though he adopts a Western narrative structure and formal use of time, Ray avoids the closure found in the classical Hollywood archetypes he so admired. In the last scene of The Big City, a working woman and her husband set out into Calcutta, searching the vast metropolis for work, uncertain about their future and how they will support their children beyond their mutual love. In the last shot of Charulata (1964), based on Tagore’s novella Nastanirh (The Broken Nest), an unfaithful wife reaches out to her husband and, just before their hands touch to confirm that all is well, Ray freezes the frame, locking their marriage in sustained ambiguity. In a scene like this, Ray does not pass a moral judgment or apply a social code of ethics as many classic Hollywood films enforced, guided by the Production Code Administration’s oversight. Ray acknowledged that his films are not Hollywood confections with conspicuous polish and gimmicks, admitting, “I am aware that they are not of a kind that hits one in the solar plexus.”

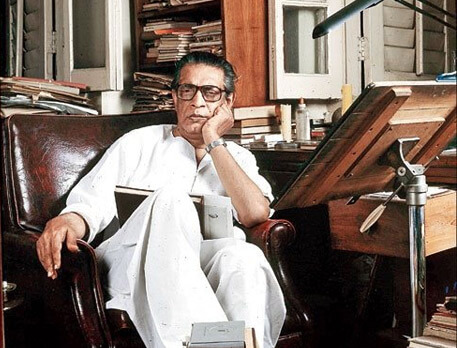

Over the next several decades, Ray continued making films and living in Kolkata, releasing a new title nearly every year between 1955 and 1981 when, due to health complications, his work began to slow. Although Ray flirted with the idea of going Hollywood in the 1960s, he never committed and preferred instead to maintain his artistic freedom. If that meant living a modest lifestyle, so be it. He guarded his inner life and distrusted people due to their rampant insensitivity and insincerity, valuing honesty, candor, intelligence, and creativity instead. Spied in the many documentaries about the director, Ray lived a poor life compared to most filmmakers, even Mumbai celebrities, having never owned a home or apartment; his flat in Kolkata was somewhat ragged and filled with books and records, his favorite chair and art supplies, as his films earned him little fortune. Despite his international celebrity as a filmmaker, he earned his living from writing projects. In his later years, Ray worked on a children’s monthly magazine, Sandesh, which was originally started by his father, penning stories, illustrating, and creating puzzles. His autonomy aside, Ray received the usual string of awards and recognition that many masters who were ignored in their heyday acquire in their twilight. He received an honorary doctorate at Oxford in 1978 and, at the time, was only one of two filmmakers to receive such distinction (the other was Charles Chaplin, Ray’s idol). He also received an honorary Academy Award just before his death in 1992 for “his rare mastery of the art of motion pictures and for his profound humanitarian outlook, which has had an indelible influence on filmmakers and audiences throughout the world.”

The worldwide appreciation of Ray’s cinema did not develop until after his death, and with it were claims of his universal appeal. And yet, curiously, his films were rarely distributed in the United States on any grand scale after Pather Panchali’s debut, especially outside of New York, Los Angeles, or San Francisco film festivals. But Ray’s name remained well-known and revered by reputation, despite few screenings of his films after the 1960s. As Robinson noted, when the late critic and scholar Richard Schickel was asked to create a highlight reel of Ray’s body of work for his 1992 Lifetime Achievement Academy Award, he couldn’t find any quality prints in America to complete the project and had to reach out to Ray himself to gather materials. Underlining this fact is simply to address that, during his lifetime, Ray’s cinema was not seen as universal, at least not by distributors who would rather choose a Japanese or French film for U.S. audiences. Only after his death did Ray’s films become the subject of restorative efforts by the Academy of Motion Pictures Archive, the Ray Film and Study Center of the University of California-Santa Cruz, the Merchant-Ivory Foundation, and The Criterion Collection.

Ray scholar Keya Ganguly argues that the idealized universality within Ray’s work “dissimulates parochial-ism and particularity.” As it has been shown, audiences exploring and assessing Ray’s films find themselves immersed in a compassionate cinema, distinguished by the filmmaker’s individual artistic, cultural, and aesthetic influences that, in their specificity, are anything but universal. Ray bears a unique cultural cosmopolitanism, but he remains a product of postcolonial subjectivity, an intellectual class that accepts Western ideas and combines them into traditional Bengali beliefs, an authority on art and music, a film enthusiast, and a thoughtful artist-filmmaker. As Robinson observed, Ray “conveys through his films a sense of a whole personality, in the same way that great writers, painters, composers and musicians do.” The Music Room is one of the truest evocations of this statement. His outlook, while worldly and humanist, is rooted in an Indian perspective and cultural foundation, but audiences everywhere connect to his sense of compassion and understanding of his characters’ complicated inner lives. Ironically, it is often the most culturally intricate and distinct characters that prove widely relatable, and ultimately misconstrued as universal, while becoming sites of profound empathy.

Bibliography:

Armes, Roy. Third World Film Making and the West. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987.

Dissanayake, Wimal. “Rethinking Indian Popular Cinema Towards Newer Frames of Understanding” Rethinking Third Cinema. Gunerante, Anthony R., and Wimal Dissanayake, editors. Routledge, 2003.

Ganguly, Keya. Cinema, Emergence, and the Films of Satyajit Ray. University of California Press, 2010.

Robinson, Andrew. Satyajit Ray: The Inner Eye. Second Edition, I.B. Tauris, 2004.

Roy, Binayak. “Ray: The Last Phase.” Film International, vol. 10, no. 2, June 2012, pp. 42-52.

Sengoopta, Chandak. “‘The Fruits of Independence’: Satyajit Ray, Indian Nationhood and the Spectre of Empire.” South Asian History and Culture, vol. 2, no. 3, 01 July 2011, p. 374-396.

—. “‘The Universal Film for All of Us, Everywhere in the World’: Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali (1955) and the Shadow of Robert Flaherty.” Historical Journal of Film, Radio & Television, vol. 29, no. 3, Sept. 2009, pp. 277-293.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review