The Definitives

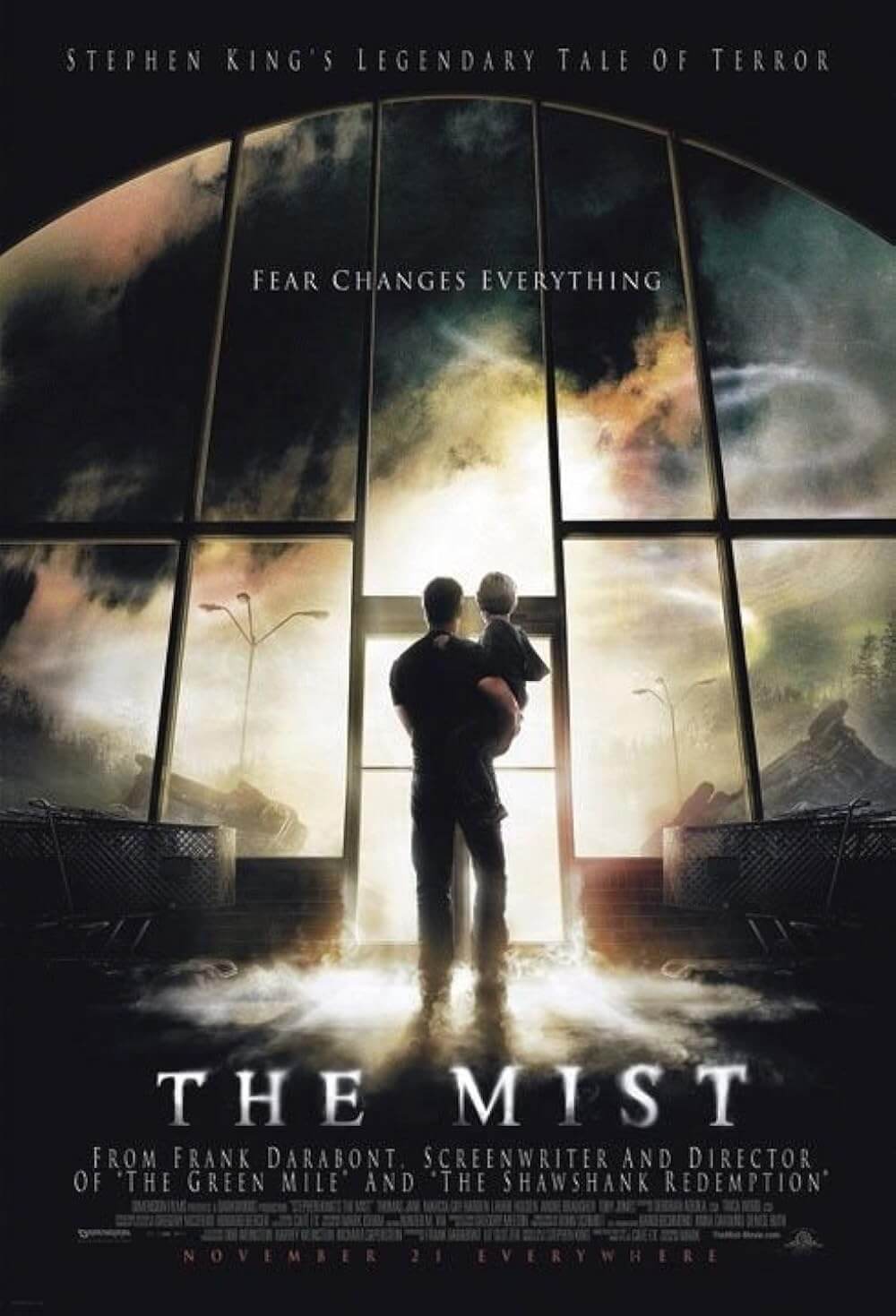

The Mist (2007)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Fear of the Unknown. Horror has long contemplated the relationship between that which lurks in the darkness and the fear thereof. While the genre often attempts to illuminate unseen terrors in monster form, using symbols like vampires and werewolves as representational devices, not seeing a thing preserves its power. Concealed behind a human face, less perceptible than any ghoul or creature of the night, people have it within themselves to reach unyielding extremes of horror. Their unpredictability makes them dangerous, as their fear controls their actions. When confronting the Unknown, the thing to fear is not the faceless monstrosity but how humanity will react to it. No modern writer knows this better than Stephen King, whose stories speak of the inborn potential for human evil when human beings are confronted by the Unknown. Frank Darabont’s film of King’s novella The Mist involves horrible, slimy, fantastical things obscured by the indefinite. Massive tentacles attached to impossible giants emerge from a vaporous shroud, reaching out from their foggy nightmare into reality; and rather than protect themselves from the Unknown, people turn on each other. Herein lies an allegory for humanity’s cleverly veiled malevolence, which, hidden behind the guise of civilization and the delusion of progress, surfaces everywhere from historical atrocities to the quiet neighbor who turns out to be a murderer. Darabont’s film is less about monsters than the simple evil of the human beast: a primal animal capable of unspeakable horrors when its perceived order to the universe proves false.

First published in 1980 in the horror anthology Dark Forces, he expanded the story five years later in Skeleton Crew. Darabont had long considered it for adaptation, and King granted the director feature film rights after approving of The Shawshank Redemption (1994) and The Green Mile (1999), the writer’s two prison novels adapted by Darabont into beloved dramas. However, despite the many awards and later honors earned by those films (the former title regularly tops lists of the best films ever made), Darabont’s script for The Mist was rejected by several studios and thought to be too bleak a vision for commercial cinema—certainly nothing like King’s life-affirming tales of hope and sentimentality that Darabont had adapted before. When his production at last found a studio, his budget was small and his shoot swift. The approach was that of a maverick. Darabont had shifted styles from the meditative, leisurely paced quality of his earlier directorial efforts, from his King adaptations to the underrated drama The Majestic (2001). Instead, The Mist bears a closer resemblance to Darabont’s work as a screenwriter on B-movies like the 1986 remake of The Blob. After all, the film concerns itself with the self-destruction of the human race, themes that hardly call for a temperate, measured, and elegant production.

Shot in 37 days using his camera crew from The Shield, the television program for which Darabont had directed a number of episodes, the film takes a desired cinéma vérité tone, rendering the experience unsettlingly authentic. The story is told through grain and ruggedness, contrasting the formal sophistication required for the director’s prison dramas. And though released theatrically in color, the home video release featured “The Director’s Vision,” being a gorgeous black-and-white cut of the film. Painstakingly remastered in high-contrast monochrome using the same process that the Coen Brothers used for their 2001 release The Man Who Wasn’t There, Darabont’s ostensible Director’s Cut furthers his allegorical intentions and emphasizes the story’s enduring commentary. In its colorless form, his already great piece of filmmaking becomes something wholly brilliant—a horror film rich with ideas about the lows of humanity. The black-and-white version, reconstructed frame by frame, avoids obviously layered gradations, washing away any mistrust of computer-animated monsters that looked phony in the color version. The audience is free to contemplate what the story means, and instead of losing themselves in a picture about creepy-crawlies and bloody violence, Darabont’s audience can contemplate the danger of fear.

Shot in 37 days using his camera crew from The Shield, the television program for which Darabont had directed a number of episodes, the film takes a desired cinéma vérité tone, rendering the experience unsettlingly authentic. The story is told through grain and ruggedness, contrasting the formal sophistication required for the director’s prison dramas. And though released theatrically in color, the home video release featured “The Director’s Vision,” being a gorgeous black-and-white cut of the film. Painstakingly remastered in high-contrast monochrome using the same process that the Coen Brothers used for their 2001 release The Man Who Wasn’t There, Darabont’s ostensible Director’s Cut furthers his allegorical intentions and emphasizes the story’s enduring commentary. In its colorless form, his already great piece of filmmaking becomes something wholly brilliant—a horror film rich with ideas about the lows of humanity. The black-and-white version, reconstructed frame by frame, avoids obviously layered gradations, washing away any mistrust of computer-animated monsters that looked phony in the color version. The audience is free to contemplate what the story means, and instead of losing themselves in a picture about creepy-crawlies and bloody violence, Darabont’s audience can contemplate the danger of fear.

The morning after an aggressive electrical storm, citizens of Bridgton, Maine are without power. The wind and rains from the night before have given way to an eerie post-storm tranquility, and in the distance, a mist slowly rolls in from nearby mountains. Family man David Drayton (Thomas Jane), a painter of movie poster art, worries about insurance and spoiled food before heading into town for supplies. His five-year-old son, Billy (Nathan Gamble), and his stranded lawyer neighbor, Brent Norton (Andre Braugher), tag along, while his wife stays home to clean away debris. Military vehicles pass them on the road, and when they arrive at the local grocery store, The Food House, they find Bridgton’s citizens stocking up. As Drayton shops and watches Bridgton’s finest all in a fluster over the power outage, air raid sirens sound. Townsman Dan Miller (Jeffrey DeMunn) runs into the store from the parking lot, panicky, and behind him a blanket of white engulfs everything. With blood running from his nose, Miller warns everyone not to go outside. “Something in the mist took John Lee!”

Miller cannot say what that something was, just that it grabbed Lee and presumably killed him in the mist—the very same mist that rolled over the mountains and that has now overtaken the entire town. Speculation goes wild as Bridgton’s small town folk make their best guesses. Maybe the Old Mill finally exploded. Maybe some kind of toxic chemicals leaked. Maybe that “Arrowhead Project” up at the military base caused it. Mrs. Carmody (Marcia Gay Harden), the town’s unhinged religious fanatic, whispers to herself, “It’s Death.” Her first thought goes to Judgment Day and proving herself to God as a loyal subject. David keeps quiet and comforts Billy. Norton, ever the attorney hungry for facts, asks everyone to remain calm, but he asserts this is nothing supernatural; rather, it’s just a man-made or freak natural occurrence that will be explained away in due time. One woman (Melissa McBride) pleads for someone to walk her home. She left her two young children there alone. No one will take her, even though she pleads through tears. She goes alone. And while those who stay behind dismiss Miller’s more vague claims, they remain too afraid of the Unknown to leave the supermarket and escort the woman to safety.

Separated from the group and attempting to fix the store’s generator in the loading dock, David and three others, including clerk-cum-hero Ollie Weeks (Toby Jones), witness a stock-boy ripped apart and dragged into the mist by anonymous tentacles reaching in from outside. To what massive creature do these tentacles belong? Though it’s impossible to tell, going out there is no longer an option. But how can they inform everyone else, who are already scared beyond reason, without causing a panic? They approach Norton, who laughs off their claims as a sick practical joke. Others see a leftover piece of the tentacle, which only escalates their fear. Soon it becomes apparent that something extraordinary and terrible is in the mist. Regardless, Norton and his band of realists refuse to wait any longer; they mean to walk out there and get help. When they do, David convinces one of them to go with a rope attached to his waist. “It’ll let us know you at least got three hundred feet.” As the explorers go out into the mist, David unravels rope until, all at once, it tightens and pulls high into the air. When they heave the rope back, they find that nothing but the man’s lower half remains.

Separated from the group and attempting to fix the store’s generator in the loading dock, David and three others, including clerk-cum-hero Ollie Weeks (Toby Jones), witness a stock-boy ripped apart and dragged into the mist by anonymous tentacles reaching in from outside. To what massive creature do these tentacles belong? Though it’s impossible to tell, going out there is no longer an option. But how can they inform everyone else, who are already scared beyond reason, without causing a panic? They approach Norton, who laughs off their claims as a sick practical joke. Others see a leftover piece of the tentacle, which only escalates their fear. Soon it becomes apparent that something extraordinary and terrible is in the mist. Regardless, Norton and his band of realists refuse to wait any longer; they mean to walk out there and get help. When they do, David convinces one of them to go with a rope attached to his waist. “It’ll let us know you at least got three hundred feet.” As the explorers go out into the mist, David unravels rope until, all at once, it tightens and pulls high into the air. When they heave the rope back, they find that nothing but the man’s lower half remains.

Taking refuge within the shelter of the grocery store, the survivors resolve to wait out the phenomenon, and in doing so, they expose themselves to the horrors inside its walls. Rattled witnesses of the bizarre shapes in the mist come close to panic, until Mrs. Carmody preaches her thoughts to the group. She tells them that this is the End of Days, that God has once again become wrathful, and that He now wants retribution for their sins. “There’s no defense against the will of God,” she says. “There’s no court of appeals in hell. The end times have come; not in flames, but in mist.” Simply put, God demands blood. Her solution: expiation, which translates into human sacrifices to the mist and to the monsters that attack at night. Mrs. Carmody’s zealous religious extremism is laughed off at first, but when her pseudo-prophesies happen to play out, beginning with giant locust-like insects taking a life, she gains followers. Lots of them.

David’s group not only defends against the encroaching menace from the Great Beyond, but they must combat the quick growth of religious hysteria booming inside the store. As Mrs. Carmody’s believers gather, her sect controls the decisions made for the entire group. Faced with the Unknown, those inside the store explain away their situation with her fervent rationalizations for an otherwise irrational situation. Ollie Weeks observes, “They’ve lost their sense of proportion.” Only David and a handful of others resist Mrs. Carmody, while others still give up altogether; they find a woman dead from suicide by pills. After a mere two days, some believe that the mist will never leave, that monsters will keep coming unless they satisfy God’s desire for penance. It’s shocking but not unbelievable how quickly these people resort to the most convenient, comforting explanation rather than confront the Unknown. When the power goes out and the establishment crumbles, what is left except the root of our dangerous belief systems? And even as David battles Mrs. Carmody’s frenzied group, he cannot stop her from expiating a soldier who confesses that military scientists may be responsible for the mist.

Just as King did when he wrote the story, Darabont follows horror master H.P. Lovecraft when conceiving his movie monsters, which attack the store at night and appear during the day’s white haze to carry off Mrs. Carmody’s offerings. With the small glimpses the director gives of them, they take no known monster iconography; instead, they appear to be unique assemblages of twisting animal parts yet other-worldly in design. After seeing Guillermo del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) and admiring the stunning creatures of that film, Darabont sought out the Mexican director’s frequent effects collaborators at Café FX for makeup and computer imagery. Those splintery, insect-inspired designs seem to exist on the same plane as the characters in Darabont’s black-and-white presentation, increasing their (otherwise unnatural) realism as three-dimensional beings within the frame. This effect is lost in color.

Just as King did when he wrote the story, Darabont follows horror master H.P. Lovecraft when conceiving his movie monsters, which attack the store at night and appear during the day’s white haze to carry off Mrs. Carmody’s offerings. With the small glimpses the director gives of them, they take no known monster iconography; instead, they appear to be unique assemblages of twisting animal parts yet other-worldly in design. After seeing Guillermo del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) and admiring the stunning creatures of that film, Darabont sought out the Mexican director’s frequent effects collaborators at Café FX for makeup and computer imagery. Those splintery, insect-inspired designs seem to exist on the same plane as the characters in Darabont’s black-and-white presentation, increasing their (otherwise unnatural) realism as three-dimensional beings within the frame. This effect is lost in color.

Beyond the technical aspects, however, Darabont displays a deep-rooted appreciation for designs themselves, almost exclusively through the artwork of American artist Drew Struzan. Consider David Drayton’s painting studio from the first shot of the film; on the character’s wall, Darabont shows us a framed piece of original poster art from The Thing, John Carpenter’s 1982 masterpiece where, expanding from Lovecraftian archetypes, creatures are brought from out of the darkness, showing their gory tendrils and bloodily morphing parts. Drayton paints an image from King’s book The Dark Tower, and beside him rests a graphic from The Shawshank Redemption—all Struzan originals. Darabont’s love of the material flows through these first scenes and spills over into the film’s marketing. Even The Mist’s initial limited edition poster was painted by Struzan, whose work includes the art for the Blade Runner, Indiana Jones, and Star Wars franchises. By including these images within the film, Darabont seems to acknowledge the long history of the genre’s iconography, which he intentionally avoids in his own creature design and art direction.

By resisting precise definitions to his monsters or exact references to the period, Darabont assembles a timeless allegory about the fearful, paranoid nature of humanity. In discussing what they should do about Mrs. Carmody, a schoolteacher (Laurie Holden) tells David and the others that they should wait; she believes people are basically good and will see Mrs. Carmody as the extremist she is. Weeks replies, “As a species we’re fundamentally insane. Put more than two of us in a room, we pick sides and start dreaming up reasons to kill one another. Why do you think we invented politics and religion?” Acknowledging the collective shock and paranoia around them, David leads a small band out of the store, away from Mrs. Carmody and her increasingly violent religious faction. Just before they escape, David’s group is stopped at the door and encircled by Carmody’s mob; their liberation comes only when Weeks shoots Carmody down, leaving her followers without a leader and therefore no answer to where they stand within their collective fog.

Instead of glorifying the remaining survivors as pseudo-heroes who conquered their fears, and in that the Unknown, Darabont provides an alternate, grim conclusion to King’s story, worthy of the film’s prior sentiments on humanity. And though it detracts from his own writing, King praised the new ending for its audacity, the way it confronts the audience with such a frontal assault of the story’s themes. David, and the four others, including his son, that made it with him through the mist to his vehicle in the store’s parking lot, drive until the gas gauge reads empty. Until this point, the film’s mostly recessive music gives way to a haunting chant, “The Host of Seraphim” by Dead Can Dance, issuing what Darabont called a “requiem mass” for humanity. Drifting in and out of the mist, the survivors pass the Drayton household, where David sees his wife’s cocooned corpse. They continue on, stopping as a six-legged thing, hundreds of feet tall, larger than any dinosaur, slogs along the road. All hope is gone when the gas runs dry and they hear hissing in the distance. Everyone exchanges futile glances. David checks his gun. There are four bullets but five of them. Out of mercy, David shoots the others, including his child. He steps outside the vehicle and screams for the monsters to take him away. And when, to David’s horror, the tanks emerge from the mist, revealing the military rescue operation, with hissing flamethrowers and trucks filled with patient survivors, his screams become even more piercing.

Instead of glorifying the remaining survivors as pseudo-heroes who conquered their fears, and in that the Unknown, Darabont provides an alternate, grim conclusion to King’s story, worthy of the film’s prior sentiments on humanity. And though it detracts from his own writing, King praised the new ending for its audacity, the way it confronts the audience with such a frontal assault of the story’s themes. David, and the four others, including his son, that made it with him through the mist to his vehicle in the store’s parking lot, drive until the gas gauge reads empty. Until this point, the film’s mostly recessive music gives way to a haunting chant, “The Host of Seraphim” by Dead Can Dance, issuing what Darabont called a “requiem mass” for humanity. Drifting in and out of the mist, the survivors pass the Drayton household, where David sees his wife’s cocooned corpse. They continue on, stopping as a six-legged thing, hundreds of feet tall, larger than any dinosaur, slogs along the road. All hope is gone when the gas runs dry and they hear hissing in the distance. Everyone exchanges futile glances. David checks his gun. There are four bullets but five of them. Out of mercy, David shoots the others, including his child. He steps outside the vehicle and screams for the monsters to take him away. And when, to David’s horror, the tanks emerge from the mist, revealing the military rescue operation, with hissing flamethrowers and trucks filled with patient survivors, his screams become even more piercing.

Fighting for his ending over the years with weary producers and commercial-minded studios, Darabont finally convinced Dimension Films to allowed his conclusion exist on its own terms. After all, Darabont was a two-time Oscar nominee at this point. He deserves applause for this gloriously fatalistic last moment, for refusing to make the picture without that ending. King’s original, anti-climactic, hopeful-if-uncertain finale in the novella provides no statement about its subject; its character drive into the mist, unsure of where they’re going or if they’ll survive. Darabont’s finale remains as subtle as a gunshot. Four of them, in fact. The director’s version concludes on a fitting note of the harshest pessimism, suggesting that the survivors fall victim to the same hysteria that infected Mrs. Carmody. And while their fear avoided leaping suppositions about God and expiation, it overcame them enough to inspire suicide. The Mist proves to be one of cinema’s most scathing indictments of the fearful, reckless nature of humanity—how people are nothing more than a reaction to their fears.

Aside from the ending, Darabont follows the source material closely, but he refuses to adapt like other directors who assume that King’s stories, due to their success in print, will effortlessly translate to film. King has the most source-to-film adaptations of any author, except perhaps Shakespeare; but unlike the Bard, most of the author’s cinematic renditions result in B-movies and disappointing TV miniseries. Darabont knows the limits of King’s sometimes campy prose; he knows what works on the page and what works on the screen. He finds the basics of what fascinated him about the story in the first place, and along with narrative progressions more suitable for cinema, he imprints a human, cinematic substance into it. Darabont leads a shortlist of directors—among them Rob Reiner, Brian De Palma, John Carpenter, and Stanley Kubrick—with the ability to capture the essence of King’s conceptual, psychological approach, and then innovate where necessary.

Darabont also reveals himself as a fierce horror director, one conscious of how humans, not monsters, drive his story. The Mist bears a striking similarity, both visually and thematically, to George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968) in that respect. He contends that true horror makes us question humanity, as opposed to the abstract terrors lurking in the mist. His formal approach mirrors this intent, as his camera dwells on characters more than monsters. Within Darabont’s version of King’s story, the mini-societies among the survivors are wonderfully outlined and segmented, as if they were test subjects forced into a confined space for a conflict-resolution experiment, the mad scientist director documenting their slow ruin. With absolute care and respect for his characters, even though he’s working within long-established horror story tropes, Darabont depicts terrifying and dismal but decidedly human circumstances.

The Mist suggests that human nature represents an abysmal void filled with fear, and when tested, it transforms people into monstrosities of unimaginable horror. Humanity compensates by pretending to be civilized, but when the illusion of civilization breaks down, we revert to our monstrosity. Ultimately, the film offers up a recurrent Stephen King thesis: that humanity is generally cruel, and that people, at their roots, are savages. King’s mist subsists in the realm of our obscured self-understanding as a species—confused, ambiguous, and filled with horrible possibility. Our desire to control and explain the Unknown results in religious fanaticism, suspicion, and hysteria, which leads to blindness, panic, and violence. All the film’s characters risk their sanity by trying to reason themselves out of a wholly incomprehensible situation, but no such thing as reason exists, the story asserts, other than in the often grotesque ways in which humanity invents for itself.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review