The Definitives

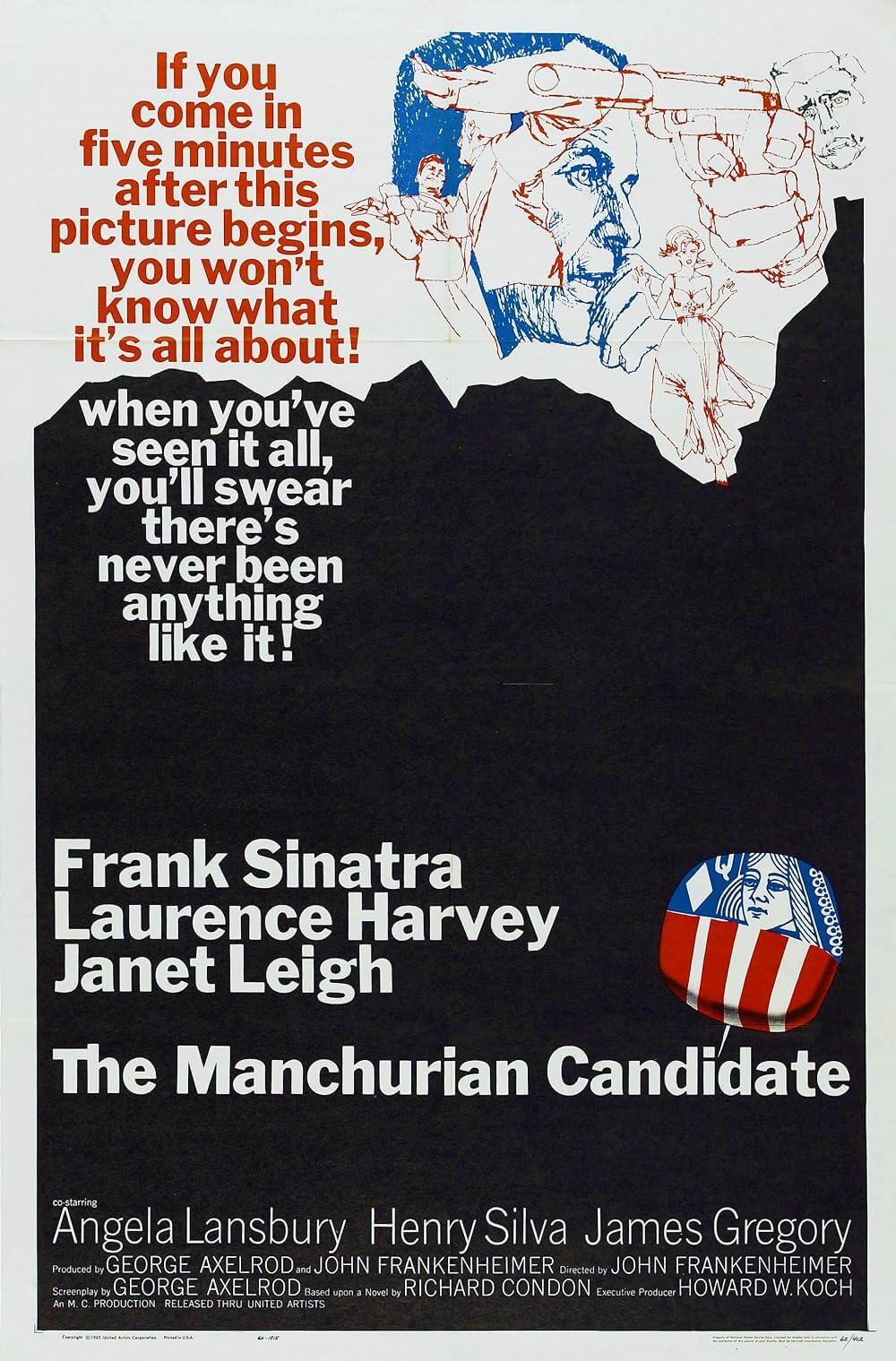

The Manchurian Candidate (1962)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

In 1961, the Justice Department and U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy were investigating Sam Giancana, a Chicago mobster who, besides mafia allegations, shared a mistress with President John F. Kennedy and attempted a CIA-sanctioned assassination of Cuban leader Fidel Castro. Frank Sinatra, whose career was made when Giancana forced jazz musician Tommy Dorsey to free Sinatra from his contract (an anecdote referenced in The Godfather), appealed to President Kennedy to back down from Giancana. Sinatra, issuing a kind of threat when JFK refused to back down, told the president how he intended to make a film of author Richard Condon’s bestseller The Manchurian Candidate. The John Frankenheimer-directed film was released October 24, 1962. Just over a year later on November 22, 1963, Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas. Among those believed to have arranged the shooting were the mob and the Cubans, although lone assassin Lee Harvey Oswald was eventually captured and ultimately killed by another lone assassin, Jack Ruby, whose own mob ties were suspect. When RFK announced his plans to run for president in March 1968, Frankenheimer was recruited to shoot all of Robert’s television appearances and promotional ads. Over the next three months, Kennedy and Frankenheimer became friends, and the director even drove the candidate to his appearance at The Ambassador Hotel on June 6, 1968. That night, Kennedy asked Frankenheimer to appear onstage with him but the director politely declined, so as not to make Kennedy appear “Hollywood”. After RFK was assassinated in the hotel kitchen following his speech, CBS newscasters mistakenly claimed that Frankenheimer was among those killed by lone shooter Sirhan Sirhan.

Life has rarely imitated art in more fantastic, catastrophic, and wildly suspicious ways than with The Manchurian Candidate, with its series of shocking coincidences and parallels to American politics. A conspiracy theorist’s mind could blow just reflecting on the connections among the film’s star, Sinatra’s mob ties and those to the President, the film’s theme of lone gunmen, presidential assassination plots implanted by communist countries, and the many correlations between the film’s paranoid framework and the secrets surrounding one of America’s most tumultuous decades, the Sixties. But this is not an examination of history fuelling sometimes outrageous theories informed by Frankenheimer’s film. Rather, this is an examination of how, within an inventive satire, a motion picture can so chillingly embody how a frightened society sees itself in a cracked mirror. Through incredible flourishes and technical mastery, Frankenheimer’s work echoes the atmosphere of paranoia surrounding The Manchurian Candidate’s release—both before and long after—to ensnare us in the film’s incomparable mixture of suspense and humor. An unpredictable experience that went overlooked in its era due to bad timing, but has since become a national treasure of American cinema, the film is so strangely funny that, if not for the events that followed its release, it might today be considered a dark comedy. But despite its eccentricities, the film remains troubling, if not horrifying for its historical parallels and reflectivity.

Published in 1959, Condon’s book was a huge success in commercial markets, but it also earned debates among literary critics and political scholars about whether or not such a thing could happen. Although Joseph McCarthy and his anti-communist rabble-rousing had seemingly ended with his death in 1957, McCarthyism had left a stain of mistrust on America. The United States had suddenly become an environment in which your neighbor and even you yourself could be accused of high treason, and the accuser didn’t even need evidence to point a finger. Eisenhower’s second term was nearing the end, and so was an era of rampant suspicion about one’s fellow countrymen and government that may have been involved in supposed espionage. Perfectly timed, Condon’s book posed a horrifying series of “What If?” questions which gripped its readers in part because they could not have been asked a decade earlier: What if the very demagogue who shouted allegations of communism was, in fact, a communist himself? Not just a communist, though, but a puppet for his puppeteer wife, who herself was a master manipulator orchestrating her husband’s rise to the presidency? And what if this Mrs. McCarthy-esque character had been in league with various communist parties to engineer herself a conditioned assassin, whom she could control to eliminate the competition? And what’s more, what if the assassin was, by chance or design, her very own progeny? Who would believe such an intricate, outlandish, absurd, yet brilliant plot? Of course, that’s the point. No one would. All the better—if no one believes it, no one tries to stop it. Indeed, Condon’s book contains a scathing view of America, but it was a reflective, self-conscious, and deliberately harsh view.

Published in 1959, Condon’s book was a huge success in commercial markets, but it also earned debates among literary critics and political scholars about whether or not such a thing could happen. Although Joseph McCarthy and his anti-communist rabble-rousing had seemingly ended with his death in 1957, McCarthyism had left a stain of mistrust on America. The United States had suddenly become an environment in which your neighbor and even you yourself could be accused of high treason, and the accuser didn’t even need evidence to point a finger. Eisenhower’s second term was nearing the end, and so was an era of rampant suspicion about one’s fellow countrymen and government that may have been involved in supposed espionage. Perfectly timed, Condon’s book posed a horrifying series of “What If?” questions which gripped its readers in part because they could not have been asked a decade earlier: What if the very demagogue who shouted allegations of communism was, in fact, a communist himself? Not just a communist, though, but a puppet for his puppeteer wife, who herself was a master manipulator orchestrating her husband’s rise to the presidency? And what if this Mrs. McCarthy-esque character had been in league with various communist parties to engineer herself a conditioned assassin, whom she could control to eliminate the competition? And what’s more, what if the assassin was, by chance or design, her very own progeny? Who would believe such an intricate, outlandish, absurd, yet brilliant plot? Of course, that’s the point. No one would. All the better—if no one believes it, no one tries to stop it. Indeed, Condon’s book contains a scathing view of America, but it was a reflective, self-conscious, and deliberately harsh view.

Frankenheimer began developing the screenplay with writer George Axelrod, screen adapter of Truman Copote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s, for United Artists in 1961. Film rights to the book had been turned down around Hollywood, the material deemed too “explosive”. When Frankenheimer read it, he jumped at the rights, putting down five thousand dollars of his own to secure the purchase price of seventy-five thousand; Alexrod did the same. Once pre-production efforts began, Sinatra was cast in the lead role of Bennett Marco, the head of an American patrol captured and brainwashed by Chinese communists during the Korean War. One among them, Staff Sgt. Raymond Shaw (Lawrence Harvey), is turned into an assassin and, upon returning home, programmed to kill a presidential candidate. Sinatra, usually hard on his directors, butted heads with Frankenheimer only once over who should play Mrs. Iselin, the inflexible wife of James Gregory’s weak-minded Senator Iselin. Right from the start Frankenheimer wanted Angela Lansbury, who had appeared in his previous picture All Fall Down (1962). Sinatra wanted his friend Lucille Ball to shed her television persona on film. But after Frankenheimer screened Lansbury’s larger-than-life performance in All Fall Down for Sinatra, the actor agreed to Lansbury enthusiastically. With a cast including the superstar Sinatra, the popular British actor Harvey, and Janet Leigh fresh off Psycho (1960), Frankenheimer’s cast was the best in his career, just as 1962 shaped up to be the director’s most prolific: Along with All Fall Down’s release in April, his long-delayed film of Birdman of Alcatraz arrived in June of that year, followed by The Manchurian Candidate in October.

Several critics praised The Manchurian Candidate and many called it the best picture of 1962, but audiences did not respond—perhaps having had enough of Cold War paranoia—and the film only did modest business in its initial run. For the 1963 Academy Award ceremony, Lansbury was nominated for Best Supporting Actress and a Best Editing nomination went to Ferris Webster. Several months later, widespread curiosity toward the picture piqued after President Kennedy’s devastating assassination, the parallel between life and art too similar to deny yet too intangible to fully grasp. Still, United Artists considered redistributing the film to exploit the renewed interest, a crude notion which Frankenheimer, Sinatra, and Alexrod were quick to deny. The Manchurian Candidate was pulled from circulation following the president’s death and appeared at infrequent public screenings over the coming years. Sinatra spent the better part of three decades attempting to shield the film from release, hoping to prevent United Artists from garnering profits by way of Kennedy’s death. Time heals all wounds of course. In 1988, when the New York Film Festival gave the film a special screening, renewed interest from the film community meant distributors could, now with the support of Sinatra (who contributed $2 million to redistribute the film and called his own performance a career-best), re-release the picture back into national circulation. Heavily attended and universally praised, the film made profits and found a wider commercial audience. It was the rediscovery of an American masterpiece.

Following the prologue’s capture of the American platoon in Korea, the film picks up two years later in 1954, after Marco has written an accommodation for Shaw to win the Congressional Medal of Honor. Shaw now resides in New York City as an associate for a left-wing newspaper mogul, far away from his despised right-wing mother and stepfather. In Washington D.C., Marco has been plagued by nightmares about what he suspects is his platoon’s capture, brainwashing, and conditioning. His vague impressions are not clear memories but images in his unconscious mind; he knows something is wrong when he’s asked about Shaw, an insufferable prude, and as if programmed he automatically responds, “Raymond Shaw is the kindest, bravest, warmest, most wonderful human being I’ve ever known in my life.” He expresses his concerns to his Army Intelligence superiors, who in turn suggest Marco needs a leave. After all, the Major is a wreck and he looks it; Sinatra’s upper lip and brow carry a perpetual layer of nervous sweat in the film, his cheek twitching from time to time. The character’s apartment is littered with an array of random books to occupy his mind—titles like Diseases of Horses, Modern French Theater, and Jurisprudential Factor of Mafia Administration. Other soldiers from the platoon, Marco discovers, have been afflicted by the same dream. It all leads to one conclusion: their platoon has been altered to respond to two triggers. The first occurs when someone says, “Why don’t you pass the time by playing a little solitaire?” The subject then begins to deal cards for himself as if in a trance, until he reaches the Queen of Diamonds card, the command trigger, at which point the subject is ready to carry out whatever orders he’s given.

Following the prologue’s capture of the American platoon in Korea, the film picks up two years later in 1954, after Marco has written an accommodation for Shaw to win the Congressional Medal of Honor. Shaw now resides in New York City as an associate for a left-wing newspaper mogul, far away from his despised right-wing mother and stepfather. In Washington D.C., Marco has been plagued by nightmares about what he suspects is his platoon’s capture, brainwashing, and conditioning. His vague impressions are not clear memories but images in his unconscious mind; he knows something is wrong when he’s asked about Shaw, an insufferable prude, and as if programmed he automatically responds, “Raymond Shaw is the kindest, bravest, warmest, most wonderful human being I’ve ever known in my life.” He expresses his concerns to his Army Intelligence superiors, who in turn suggest Marco needs a leave. After all, the Major is a wreck and he looks it; Sinatra’s upper lip and brow carry a perpetual layer of nervous sweat in the film, his cheek twitching from time to time. The character’s apartment is littered with an array of random books to occupy his mind—titles like Diseases of Horses, Modern French Theater, and Jurisprudential Factor of Mafia Administration. Other soldiers from the platoon, Marco discovers, have been afflicted by the same dream. It all leads to one conclusion: their platoon has been altered to respond to two triggers. The first occurs when someone says, “Why don’t you pass the time by playing a little solitaire?” The subject then begins to deal cards for himself as if in a trance, until he reaches the Queen of Diamonds card, the command trigger, at which point the subject is ready to carry out whatever orders he’s given.

In particular, the exceptional aspect about Marco’s dream sequence is how it avoids all clichéd dream imagery from this era of cinema. Had The Manchurian Candidate been a standardized film, the sequence might have been more like the surrealist, stereotypically Freudian, Dali-designed nightmares from Alfred Hitchcock’s Spellbound (1945). Instead, Frankenheimer slowly hands over information about what’s really going on as though dealing cards from a deck, one by one until we see the full hand on display. First, the viewer sees a ladies club and its speaker giving a lecture on hydrangeas, the background a hotel event room decorated with floral accruements. In a single shot, the camera pans around to show the women in attendance, revealing Marco and his platoon sitting on the stage, aloof, yawning, unaware. The presenter goes about her garden club meeting and by the time the frame comes full circle, the seminar stage has been replaced with hanging photographs of Joseph Stalin and Mao Zedong. Now the speaker, Dr. Yen Lo (Khigh Dheigh) of the Pavlov Institute, addresses an assorted audience of communist dignitaries about how he’s “brainwashed” the American soldiers. At any moment during the sequence, Frankenheimer replaces one element of the flower lecture conditioning with the horrifying reality, interweaving the horticulturist with Dr. Lo’s chummy remarks like a deck of shuffled cards. From Marco’s point of view, it looks as though the ladies club orator is speaking about the conditioning of American soldiers as programmed assassins. The sequence might be hilariously incongruous if it didn’t end with Dr. Lo instructing Shaw to strangle one of his fellow soldiers and then shoot another at point-blank range in the face.

After the dream sequence, the viewer cannot help but second guess everything that follows it. At any moment, our hero might slip into his conditioned point of view which, as Frankenheimer has demonstrated, blends perfectly with reality. How can we know the difference? How can we know who’s a communist and who isn’t? As with McCarthyism, we have only what we’re shown and our better judgment to rely on. In the club car on the train to New York, where he plans to meet Shaw, Marco meets Rosie (Janet Leigh), an attractive woman who takes a curious interest in him. She offers Marco a cigarette and when he fails to light it, he rushes off in a panic. Rosie follows, trying to initiate conversation and perhaps calm this nervous man. She quips, “I was one of the original Chinese workmen who laid the track on this straight.” Is this a jest on her part, a flirtation by an eccentric personality? Marco barely reacts, almost as if Rosie has somehow just activated his conditioning, but the unreadable expressions on the actors’ faces refuse to confirm our suspicions. The conversation continues, and as it continues it gets stranger. Her remark that “Maryland is a beautiful state” becomes curious when Marco points out they’re in Delaware. Once again, she says, “Maryland is a beautiful state,” as if insisting on a verbal trigger, then concedes “So is Ohio, for that matter.” Her forced, vaguely flirtatious banter might otherwise feel like an exceptionally forthright come-on—almost comparable to Eva Marie Saint and Cary Grant’s exchange in North by Northwest, but there were ulterior motives even in that film. Then again, perhaps Rosie is just as lonely and desperate as Marco and willing to try anything for company. As she suggestively reads off her home address to him, again we question her antiseptic tone: Is she activating Marco for some unknown purpose never rectified within the film, or is she just forward in her sexual advances? Condon’s book offers no answers, nor does the film. But our paranoia over Rosie is undeniable.

Fortunately, there’s nothing so uncertain about Mrs. Iselin, who must be one of cinema’s all-time greatest villains and certainly the best performance of Lansbury’s career. Pulling the strings on her husband’s campaign of fear, Mrs. Iselin, like McCarthy, hides under the guise of a patriot to control America, even while she makes plans to destabilize it. And anyone who disagrees with her is a communist. The power behind the throne, Mrs. Iselin controls her dim-witted husband and talks to him like a child, at one point telling him to “Run along, the grown-ups have to talk.” At a press conference, she mouths her husband’s hysteria rattling speech as Sen. Iselin announces the ever-changing number of card-carrying communists in the Defense Department. Later, he begs her for a consistent number, as the press has started to grill him about it; she smiles and takes the number from her husband’s bottle of Heinz 57. The Manchurian Candidate is nothing if not darkly comic. But as Mrs. Iselin treats her husband like a child, she’s also effectively (and incestuously) flip-flopped the role of her son Raymond to that of a lover. When she prevents Raymond’s happiness and forbids him from seeing the love of his life, Jocie (Leslie Parrish), daughter of Sen. Iselin’s political rival Sen. Thomas Jordan (John McGiver), her actions seem to be out of political interest. But perhaps it’s out of jealousy. In Condon’s book, the scene where Mrs. Iselin activates her son to kill the forerunning presidential candidate in the next election is followed by Mrs. Iselin taking her son to bed. Of course, censors would never allow Frankenheimer to suggest such blatant morbidity, but he nonetheless hints at incest when, after ordering Shaw to kill, she plants a long, intimate kiss on her son’s lips. The screen fades to black, and the rest is left to our imagination.

Fortunately, there’s nothing so uncertain about Mrs. Iselin, who must be one of cinema’s all-time greatest villains and certainly the best performance of Lansbury’s career. Pulling the strings on her husband’s campaign of fear, Mrs. Iselin, like McCarthy, hides under the guise of a patriot to control America, even while she makes plans to destabilize it. And anyone who disagrees with her is a communist. The power behind the throne, Mrs. Iselin controls her dim-witted husband and talks to him like a child, at one point telling him to “Run along, the grown-ups have to talk.” At a press conference, she mouths her husband’s hysteria rattling speech as Sen. Iselin announces the ever-changing number of card-carrying communists in the Defense Department. Later, he begs her for a consistent number, as the press has started to grill him about it; she smiles and takes the number from her husband’s bottle of Heinz 57. The Manchurian Candidate is nothing if not darkly comic. But as Mrs. Iselin treats her husband like a child, she’s also effectively (and incestuously) flip-flopped the role of her son Raymond to that of a lover. When she prevents Raymond’s happiness and forbids him from seeing the love of his life, Jocie (Leslie Parrish), daughter of Sen. Iselin’s political rival Sen. Thomas Jordan (John McGiver), her actions seem to be out of political interest. But perhaps it’s out of jealousy. In Condon’s book, the scene where Mrs. Iselin activates her son to kill the forerunning presidential candidate in the next election is followed by Mrs. Iselin taking her son to bed. Of course, censors would never allow Frankenheimer to suggest such blatant morbidity, but he nonetheless hints at incest when, after ordering Shaw to kill, she plants a long, intimate kiss on her son’s lips. The screen fades to black, and the rest is left to our imagination.

In spite of being a prude and admittedly “unlovable”, Raymond Shaw gathers our sympathy when he and Marco sit down for a drink and, having had too much, Raymond recounts his summer of love with Jocie. “You just cannot believe, Ben, how loveable the whole damn thing was. All summer long, we were together. I was loveable, Jocie was loveable, the Senator was loveable, the days were loveable, the nights were loveable, and everybody was loveable. Except, of course, my mother.” If her communist ties and manipulations weren’t enough, Raymond explains how his mother then forbade him from ever seeing Jocie again and enlisted him in the army. What romantic tragedy. Worse, after her son and Jocie rekindle their love by running off to get married, Mrs. Iselin programs Raymond to kill Sen. Jordan, his new father-in-law. And when Jocie witnesses the murder, he kills her too with a single bullet in the head. Frankenheimer arranges yet another scene that might be humorous if it didn’t end so shockingly. Raymond enters the Jordan’s house to find the Senator making himself a late-night snack. When he shoots, the bullet enters through a milk carton the Senator holds in front of him, and the bloodless, absurdist image of milk spilling from the carton looks as though the Senator gushes milk from his wound. The camera lingers there for a moment until, behind Raymond, Jocie screams. Without hesitation, Raymond fires and all hope for this character’s salvation from his purely evil mother has gone.

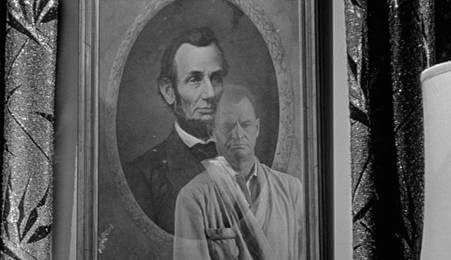

Not yet a major filmmaker, Frankenheimer seems to have asked himself “What can I get away with?” and in turn loads the film’s mise-en-scène with equal measures of realism and visual metaphor. Production designer Richard Sylbert (Chinatown and Rosemary’s Baby) embeds details that make the impossible seem real, and the real seem joyously peculiar—everything Sylbert does makes the film appear un-staged and encumbered by realistic facets, so we question less what might otherwise seem out of place. For his own style, Frankenheimer borrowed from (who better than) masters like Hitchcock and Orson Welles in his deep focus photography and visual puns, but also from French New Wave filmmakers like Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad (1961) or François Truffaut’s Shoot the Piano Player (1960) in terms of rule-breaking. Moreover, the humor injected into this tale of murder, conspiracy, and shattered minds reminds one of countless Hitchcock yarns, namely Psycho (1960), while the idea of a man who cannot remember his murders was explored in the aforementioned Spellbound. Frankenheimer and Sylbert seem in perfect unison during the picture’s famous Lincoln theme, complete with portraits and busts of the 16th President of the United States strewn about the Iselin household, foreshadowing the moment when Raymond finally regains control over himself and shoots his mother and stepfather instead of his programmed target. In Condon’s book and much of the shooting script, the Lincoln theme is never present. Frankenheimer and Sylbert seem to have drawn on this themselves, connecting the audience with a knowing symbol of the growing suspense from the visual association between Iselin and Lincoln. Frankenheimer pushes the visual cue to such a wild degree that he even dresses up Iselin as Lincoln at a costume party; with false beard and black garb, the Senator removes his top hat to perform a drunken limbo.

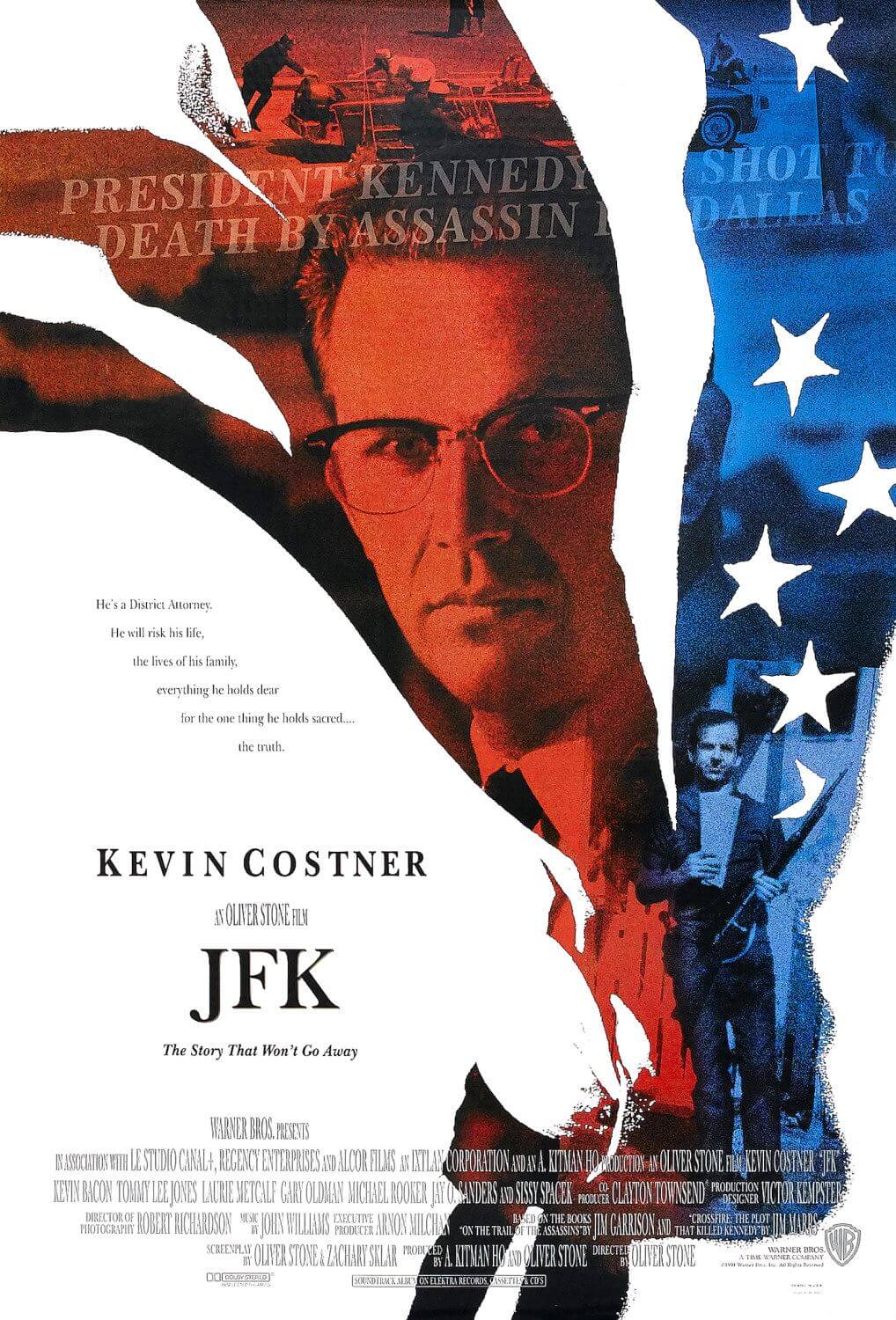

Remade in 2004 into a straight thriller by The Silence of the Lambs helmer Jonathan Demme and starring Denzel Washington, Meryl Streep, and Liev Schreiber, the remake contains none of the political and historical parallels of the original, nor does it break any Hollywood rules. The original never stops breaking rules: humor and thrills create an intentionally tremulous tone; implications of incest make us pause; milk bleeds from a gunshot wound; the innocent girl and her father are shot dead without feeling; the resident McCarthy stand-ins are gunned down in a staggering display of catharsis; the romantic interest, Rosie’s odd behavior goes unexplained; a thrilling mid-film karate fight between Marco and Henry Silva’s Chunjin is unlike anything seen in cinema at the time. This all suggests Frankenheimer has resolved to throw the rulebook out the window and test both the audience’s limits and his own limitations as a filmmaker. For viewers in 1962, perhaps the film was too much and demanded that they acclimate for more than twenty-five years. After all, no one at that time had yet been a part of the erupting assassination culture which followed in the coming years: John Kennedy in 1963 and his brother Robert in 1968; Lee Harvey Oswald in 1965; Malcolm X in 1965; Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968; Harvey Milk in 1978; John Lennon in 1980; and attempts on Pope Paul VI, Andy Warhol, George Wallace, Gerald Ford, Bob Marley, and Ronald Reagan. The list could go on. Karl Marx and many historians would argue that individuals do not make history, but in these cases just a solitary bullet does. And so, the majority of film historians, critics, and moviegoers took until 1988 to recognize how far ahead of its time Frankenheimer’s film really was.

Remade in 2004 into a straight thriller by The Silence of the Lambs helmer Jonathan Demme and starring Denzel Washington, Meryl Streep, and Liev Schreiber, the remake contains none of the political and historical parallels of the original, nor does it break any Hollywood rules. The original never stops breaking rules: humor and thrills create an intentionally tremulous tone; implications of incest make us pause; milk bleeds from a gunshot wound; the innocent girl and her father are shot dead without feeling; the resident McCarthy stand-ins are gunned down in a staggering display of catharsis; the romantic interest, Rosie’s odd behavior goes unexplained; a thrilling mid-film karate fight between Marco and Henry Silva’s Chunjin is unlike anything seen in cinema at the time. This all suggests Frankenheimer has resolved to throw the rulebook out the window and test both the audience’s limits and his own limitations as a filmmaker. For viewers in 1962, perhaps the film was too much and demanded that they acclimate for more than twenty-five years. After all, no one at that time had yet been a part of the erupting assassination culture which followed in the coming years: John Kennedy in 1963 and his brother Robert in 1968; Lee Harvey Oswald in 1965; Malcolm X in 1965; Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968; Harvey Milk in 1978; John Lennon in 1980; and attempts on Pope Paul VI, Andy Warhol, George Wallace, Gerald Ford, Bob Marley, and Ronald Reagan. The list could go on. Karl Marx and many historians would argue that individuals do not make history, but in these cases just a solitary bullet does. And so, the majority of film historians, critics, and moviegoers took until 1988 to recognize how far ahead of its time Frankenheimer’s film really was.

Historical ironies and coincidences aside, The Manchurian Candidate does not presage the coming rash of assassinations and conspiracies in the Sixties and beyond—at least not deliberately. Frankenheimer and Alexrod expanded upon Condon’s novel to recreate an atmosphere of paranoia, not political intrigue, and in turn demonstrate the insanity of the McCarthyism state-of-mind so prevalent the decade before. They imagined the worst possible direction a McCarthyist society could go, and that direction happened to coincide with their film. What remains fascinating is how the picture manages to take an apolitical stance and argues neither for the left side or the right. If at all condemning, it condemns a circle of propaganda and paranoia fuelling opposing sides of the Cold War. It’s not a film with a side that needs to be agreed with; it’s a film that engulfs its audience in a mood that loomed over the United States like a miasma. Frankenheimer takes us down the rabbit hole, cleverly employing almost documentary-style realism infused with a corrosive sense of humor. In full control of every formal element at his disposal, Frankenheimer’s The Manchurian Candidate is a masterwork of parodic cynicism, edgy stylization, and nerve-racking suspense. And however exhilarating it may be that this thriller about a time of mistrust and paranoia still remains effective and relevant today, there’s also something scary and disparaging in that fact.

Bibliography:

Armstrong, Stephen B. Pictures About Extremes: The Films of John Frankenheimer. London: McFarland & Company, Inc: 2008.

Marcus, Greil. The Manchurian Candidate. British Film Institute, 2002.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review