The Definitives

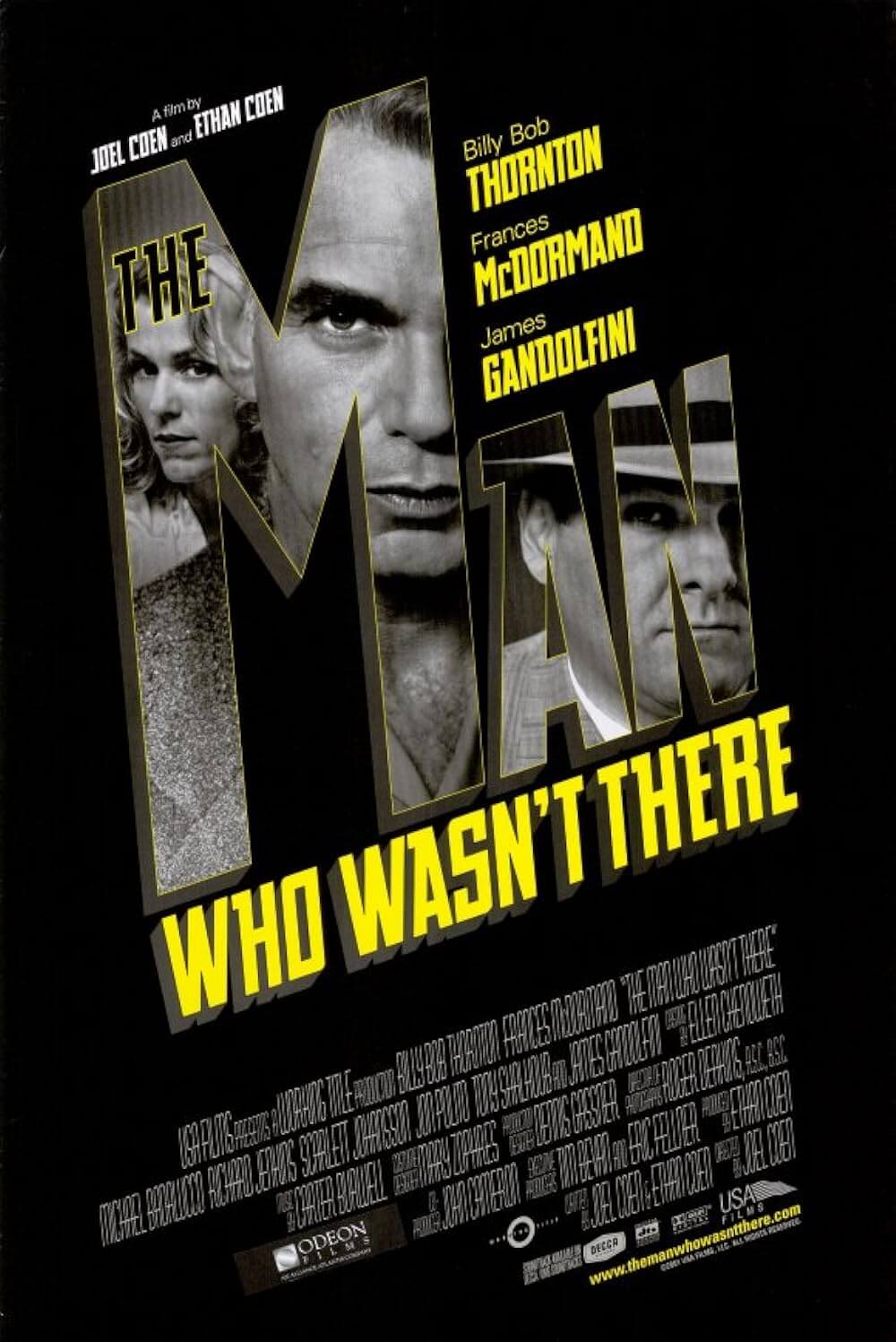

The Man Who Wasn’t There (2001)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

The Coen Brothers’ The Man Who Wasn’t There has a perfect film noir opening, a monologue in voiceover that captures its protagonist’s unaffected, yet exacting, observations about his métier, his family, and his detachment from the world and those who inhabit it. His name is Ed Crane. Ed is The Barber. He’s invisible, internal, his thoughts running endlessly as he cuts hair. If you were in a room with him, you might not even notice save for the smell of his omnipresent cigarette. “Yeah, I worked in a barbershop,” he admits. “But I never considered myself a barber. I stumbled into it—well, married into it more precisely. It wasn’t my establishment… Like the fella says, I only work here. The dump was 200 feet square, with five chairs. Or stations as we call ’em, even though there were only two of us working. Frank Raffo, my brother-in-law, was the principal barber. And man, could he talk. Now maybe if you’re eleven or twelve years old, Frank’s got an interesting point of view. But sometimes it got on my nerves. Not that I’d complain, mind you. Like I said, he was the principal barber. Frank’s father August—they called him Guzzi—had worked the heads up in Santa Rosa for thirty-five years until his ticker stopped in the middle of a Junior Flat Top. He left the shop to Frankie free and clear. And that seemed to satisfy all of Frank’s ambitions: cutting the hair and chewing the fat. Me, I don’t talk much… I just cut the hair.” And through such wordy and steely narration, Ed Crane becomes an archetypal noir character.

Billy Bob Thornton plays Ed in a film painstakingly stylized as a film noir of crisp black-and-white photography, enveloped in shadows and an air of impassionate hopelessness. Though he hardly talks in The Man Who Wasn’t There otherwise, Ed speaks in that familiar noir device of narration, his internal speech a constant presence throughout the film (and so you’ll pardon this enthusiast if too many quotes from Ed are included). His observations are carried along by Carter Burwell’s score of what seem like funerary Beethoven piano sonatas, the film’s pace moving through its events almost as somberly as its protagonist. The Coens submerge their presentation in boundless atmosphere, moody and blackly comic, designed to echo the classic film noirs of the 1940s, specifically those of writer James M. Cain. And yet, beyond Ed, The Man Who Wasn’t There is also a story of blackmail and murder, full of twists and turns as much as it is, in true Coen Brothers form, an existential exploration into the meaninglessness of the universe. Through the Coens’ film noir narration, they put forth an introspective protagonist who, for all intents and purposes, lives in his own head. At one point Ed describes life as a maze: “You go through willy-nilly, turning where you think you have to turn, banging into the dead ends, one thing after another.” But then, he resolves that, pulling back from the maze, you see the full picture and come to some level of understanding. The tragedy of Ed finding some perspective when he does in the film is that it comes only on the eve of his execution.

Roger Ebert called the film “the portrait of a man so trapped by life he wants to scream,” but Ed Crane never wanted to scream. To be a man like that, the man has to know what he wants, and what he wants must be just out of reach. Ed has little more than utter disinterest and uninvolvement for what happens in the world. There may be a yearning inside of him, but for what he does not know, and so he cuts the hair. That’s good enough. He listens to his brother-in-law (Michael Badalucco) blather on all day about French traders, fly fishing, and how to best start a flooded vehicle, and all the while Ed cuts the hair. Other people have hobbies, which Ed thinks are “screwy”, and so he cuts the hair. Take his pushy wife, Doris (Frances McDormand), who loses herself in the glamour supplied by amenities at Nirdlinger’s, the department store where she works for Big Dave (James Gandolfini), a braggart war hero with whom she’s having an affair. “Not that I was gonna prance about it, mind you,” Ed says about his wife’s infidelity. “It’s a free country.” Stuck in a job he doesn’t mind but isn’t passionate about, in a marriage where he’s being cuckolded, you might consider Ed a loser, a schlub. He’s just The Barber, nothing more, though it’s an identity he occupies thanklessly but without complaint. Remember, he never considered himself a barber; he remains outside himself, a spectator to his own dull existence. Indeed, Ed knows what he doesn’t like but couldn’t tell you what interests him, until talky salesman Creighton Tolliver (Jon Polito) sits in his chair and pitches a newfangled idea called dry cleaning, which piques Ed’s interest to such a degree that it impels him to crime.

Roger Ebert called the film “the portrait of a man so trapped by life he wants to scream,” but Ed Crane never wanted to scream. To be a man like that, the man has to know what he wants, and what he wants must be just out of reach. Ed has little more than utter disinterest and uninvolvement for what happens in the world. There may be a yearning inside of him, but for what he does not know, and so he cuts the hair. That’s good enough. He listens to his brother-in-law (Michael Badalucco) blather on all day about French traders, fly fishing, and how to best start a flooded vehicle, and all the while Ed cuts the hair. Other people have hobbies, which Ed thinks are “screwy”, and so he cuts the hair. Take his pushy wife, Doris (Frances McDormand), who loses herself in the glamour supplied by amenities at Nirdlinger’s, the department store where she works for Big Dave (James Gandolfini), a braggart war hero with whom she’s having an affair. “Not that I was gonna prance about it, mind you,” Ed says about his wife’s infidelity. “It’s a free country.” Stuck in a job he doesn’t mind but isn’t passionate about, in a marriage where he’s being cuckolded, you might consider Ed a loser, a schlub. He’s just The Barber, nothing more, though it’s an identity he occupies thanklessly but without complaint. Remember, he never considered himself a barber; he remains outside himself, a spectator to his own dull existence. Indeed, Ed knows what he doesn’t like but couldn’t tell you what interests him, until talky salesman Creighton Tolliver (Jon Polito) sits in his chair and pitches a newfangled idea called dry cleaning, which piques Ed’s interest to such a degree that it impels him to crime.

The noir yarn begins as Ed needs $10,000 to buy into Tolliver’s business as a silent partner, and without hesitation, he resolves to blackmail Big Dave. His anonymous note to Big Dave reads, “I know about you and Doris Crane. Cooperate or Ed Crane will know. Your wife will know. Everyone will know.” Big Dave even comes to Ed for advice, to which Ed replies that he should pay the blackmailer, whom Big Dave suspects is a businessman from Sacramento. It’s no matter to Ed. Doris two-timing him “pinched a little,” and so when Big Dave eventually delivers the money, Ed pays Tolliver, signs the contract, and waits. In the meantime, after a family wedding at which Doris gets soused and later passes out, Ed receives a call from Big Dave—he needs to talk. It’s the middle of the night and Big Dave’s call interrupts Ed’s voiceover story about how he and Doris first met on a blind date. “At the end of the night she said she liked it I didn’t talk much. A couple weeks later she suggested—” and the phone rings. Ed leaves Doris on the bed passed out and meets Big Dave at Nirdlinger’s. There’s a confrontation about the blackmail. Big Dave realizes it was Ed. There’s a struggle and Ed stabs Big Dave in the neck with Big Dave’s cigar trimmer. Big Dave dies and, with no witnesses, Ed returns home and continues his narration. “—It was only a couple of weeks after we met that Doris suggested getting married. I said, Don’t you wanna get to know me more? She said, Why, does it get better? She looked at me like I was a dope, which I’ve never really minded from her. And she had a point, I guess. We knew each other as well then as now… Anyway, well enough.” Ed’s train of thought barely seems interrupted by the murder.

Ever the stylists, Joel and Ethan Coen set their film in the world of James M. Cain, the hard-boiled crime fiction writer who authored the source material for Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity (1944), Michael Cutiz’s Mildred Pierce (1945), and The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946), starring Lana Turner and John Garfield. The stuff of Raymond Chandler, Mickey Spillane, and Dashiell Hammett, Cain’s romans noir were driven by voiceover prose like Ed’s, the kind of toughguy-speak where the cynical observations of a criminal mind or detective are edgy and biting, and reflect the unforgiving world inhabited by the character. Ed’s voiceover sounds like Cain’s prose reads, except with Thornton’s low, gruff, almost monotone voice speaking through his cigarettes—the viewer even hears audible inhales and exhales as Ed smokes through his reading. While shooting a scene for their 1950s-era screwball comedy The Hudsucker Proxy (1994) in a North Carolina barbershop, the Coens noticed a poster with the various 1940s haircuts on display; they began to think about the barber who actually cut the hair and, along with their pronounced love for Cain, set out to tell a story in Cain’s style and, at least on the surface, about a barber. Cain’s characters were always lowlifes and types on the margins of society—they have a chance to make it, and make it big, and that usually requires them to do something illegal. And they’d get away with it too if not for some insignificant detail or coincidence they’ve overlooked, which brings about their reprisals in the end.

Ever the stylists, Joel and Ethan Coen set their film in the world of James M. Cain, the hard-boiled crime fiction writer who authored the source material for Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity (1944), Michael Cutiz’s Mildred Pierce (1945), and The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946), starring Lana Turner and John Garfield. The stuff of Raymond Chandler, Mickey Spillane, and Dashiell Hammett, Cain’s romans noir were driven by voiceover prose like Ed’s, the kind of toughguy-speak where the cynical observations of a criminal mind or detective are edgy and biting, and reflect the unforgiving world inhabited by the character. Ed’s voiceover sounds like Cain’s prose reads, except with Thornton’s low, gruff, almost monotone voice speaking through his cigarettes—the viewer even hears audible inhales and exhales as Ed smokes through his reading. While shooting a scene for their 1950s-era screwball comedy The Hudsucker Proxy (1994) in a North Carolina barbershop, the Coens noticed a poster with the various 1940s haircuts on display; they began to think about the barber who actually cut the hair and, along with their pronounced love for Cain, set out to tell a story in Cain’s style and, at least on the surface, about a barber. Cain’s characters were always lowlifes and types on the margins of society—they have a chance to make it, and make it big, and that usually requires them to do something illegal. And they’d get away with it too if not for some insignificant detail or coincidence they’ve overlooked, which brings about their reprisals in the end.

Ed Crane is a model Cain character. He’s somewhat pathetic, yet sympathetic because of the first-person narrative; he’s wrapped inside his own head but cannot see the disaster awaiting him. Inspired by both Cain and an archival barbershop poster, the Coens plunge their audience into Ed’s noir world by steeping their picture in film noir mood supplied by voiceover, but also through smoky visuals of sharp black-and-white. Their longtime collaborator, director of photography Roger Deakins, shot in color and then printed the film stock on a black-and-white negative for exhibition, remastering the monochrome image in post-production. (Frank Darabont would follow the Coens’ example in 2007 with his black-and-white remastering of The Mist.) Even in 2001, when the film was released, black-and-white stock was rarely made anymore, if ever, and had not changed for several decades; but color stock was only becoming finer in the amount of detail one could capture. As a result, Deakins renders a noir world with impressive detail, the cuts infrequent, pacing unhurried, and images onscreen gorgeous enough to be framed. For every visual touch, the Coens incorporate their comic details too, those little idiosyncrasies that place The Man Who Wasn’t There in line with everything it means to be “a Coen Brothers film”. For all their considerable technical and stylistic effort, Joel Coen won the Best Director award at the 2001 Cannes Film Festival; he shared the honor with David Lynch’s work on Mulholland Drive, though it should have been shared with his brother, Ethan.

The Coens’ distinct touches in The Man Who Wasn’t There emerge from the basic noir scenario, but also the style of performances they generate. Richard Schickel noted in Time “Affectlessness is not a quality much prized in movie protagonists, but Billy Bob Thornton, that splendid actor, does it perfectly.” His brow creased, eyebrows downturned almost to a frown, and lips bent over like handlebars, Thornton’s manner reveals nothing about Ed, and Thornton has never been better outside of A Simple Plan (1998). Ed is contrasted by the Coens’ particular brand of larger-than-life characters, such as those by McDormand, Gandolfini, Polito, and Badalucco, if only to further showcase Ed’s invisible nature. Here is a protagonist who is so insignificant in his own world that, even when he admits to murder, no one would ever believe The Barber could do it. Before long, the police arrest not Ed but Doris for Big Dave’s murder. Rather than confess, Ed hires fast-talking attorney Freddy Riedenschneider (Tony Shalhoub) to defend Doris, but even as someone as prestigious as Freddy Riedenschneider has trouble conceiving a worthy line of defense after it’s discovered Doris was sleeping with Big Dave and cooking his books at Nirdlinger’s. Ed tries to accept the blame, telling Riedenschneider some version of the truth—that he killed Big Dave after learning about he and Doris’ affair. But the fast-talking lawyer says “let’s be realistic” and “that’s silly” and can’t imagine a jury who would believe The Barber, this low-key and inexpressive figure, would do it. Instead, Riedenschneider, in a way living in his own head as well, gets metaphysical and tries to work Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle into his defense. Not that it matters much; before the trial, Doris kills herself in jail.

The Coens’ distinct touches in The Man Who Wasn’t There emerge from the basic noir scenario, but also the style of performances they generate. Richard Schickel noted in Time “Affectlessness is not a quality much prized in movie protagonists, but Billy Bob Thornton, that splendid actor, does it perfectly.” His brow creased, eyebrows downturned almost to a frown, and lips bent over like handlebars, Thornton’s manner reveals nothing about Ed, and Thornton has never been better outside of A Simple Plan (1998). Ed is contrasted by the Coens’ particular brand of larger-than-life characters, such as those by McDormand, Gandolfini, Polito, and Badalucco, if only to further showcase Ed’s invisible nature. Here is a protagonist who is so insignificant in his own world that, even when he admits to murder, no one would ever believe The Barber could do it. Before long, the police arrest not Ed but Doris for Big Dave’s murder. Rather than confess, Ed hires fast-talking attorney Freddy Riedenschneider (Tony Shalhoub) to defend Doris, but even as someone as prestigious as Freddy Riedenschneider has trouble conceiving a worthy line of defense after it’s discovered Doris was sleeping with Big Dave and cooking his books at Nirdlinger’s. Ed tries to accept the blame, telling Riedenschneider some version of the truth—that he killed Big Dave after learning about he and Doris’ affair. But the fast-talking lawyer says “let’s be realistic” and “that’s silly” and can’t imagine a jury who would believe The Barber, this low-key and inexpressive figure, would do it. Instead, Riedenschneider, in a way living in his own head as well, gets metaphysical and tries to work Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle into his defense. Not that it matters much; before the trial, Doris kills herself in jail.

Ed is all but unaffected by Doris’ death. He goes back to the barbershop, while his brother-in-law loses himself to depression. For an audience, The Man Who Wasn’t There may seem soulless, purely an exercise in style. Except there’s an evident yearning in Ed Crane that emerges, albeit at a measured pace. Not unlike his dry cleaning investment, which goes south when Tolliver skips town, Ed shows interest in the piano playing of Birdy Abundas (Scarlett Johansson), the teenaged daughter of a perpetually drunk attorney and barbershop customer (Richard Jenkins, his head bobbling in a stupor). Birdy is a polite young girl whose skills at the piano represent another escape of some kind for Ed. He likes the music and visits the Abundas’ home regularly; after Doris is gone, he offers to manage Birdy and hopes she’ll become famous. Perhaps he sees Birdy as a vicarious outlet for his own failures and to make something of Birdy would be to give his own life meaning. And when a snooty French piano instructor tells Ed that Birdy “stinks” and will make “a very good typist”, Ed may have lost all hope. Driving Birdy back from her audition, Ed resists when she tries to thank him in a way he never expected from a seemingly reserved girl, and the car crashes. When he comes to, he’s in the hospital and under arrest; not for his momentary indiscretion with Birdy, but for the murder of Creighton Tolliver. The Coens cut to the “pansy” salesman’s body, looking like Shelley Winters’ submerged corpse in The Night of the Hunter (1955), discovered underwater by a swimmer and put there by Big Dave much earlier. Thinking back to Miller’s Crossing (1990), young boys have a habit of finding dead bodies in the Coen Brothers’ films.

In an ironic, Cain-style twist, Ed finds himself on trial now, and Riedenschneider is back to argue a Heisenberg-heavy defense to a jury of blank stares. ”He told them to look not at the facts, but at the meaning of the facts,” Ed explains. “Then he said the facts had no meaning.” Riedenschneider suggests that someone like “The Barber” could never have conceived not only Tolliver’s murder but Big Dave’s too, nor could such a faceless entity allow Doris to take the rap for his own crime. The jury isn’t convinced, and Ed ends up on death row, writing his story five-cents-a-word for a men’s magazine. (“So you’ll pardon me if sometimes I’ve told you more than you wanted to know,” he says, writing of Cain’s brand of wordy prose.) In the film’s strangest, most mysterious sequence, the night before Ed’s execution he awakens. His cell door is open, and he wanders outside in the courtyard to see a flying saucer hovering, shining a spotlight down on him. He nods, then goes back to his cell. Already there have been multiple references in The Man Who Wasn’t There to UFOs. After Big Dave’s murder and Doris’ arrest, Big Dave’s widow Ann (Katherine Borowitz) appears on Ed’s doorstep, her face trancelike, and tells Ed about a company trip outside of Eugene, Oregon, where Big Dave saw a spacecraft, which took him and performed experiments on him. They reported the incident to the authorities, but Ann says she believes the government or aliens or both are responsible for Big Dave’s death. Later, Ed reads about the Roswell landing in Life magazine, and now seeing or dreaming about a UFO on the eve of his execution, he wonders if there’s something more, some greater meaning or connection to these events. He cannot explain how he got where he is except to trace the events in his cold writing to the men’s magazine. Perhaps UFOs are to blame, or perhaps they represent the Unknown element in Ed’s life—that missing quality in him, which everyone around him seems to have but he, at least outwardly, does not.

In an ironic, Cain-style twist, Ed finds himself on trial now, and Riedenschneider is back to argue a Heisenberg-heavy defense to a jury of blank stares. ”He told them to look not at the facts, but at the meaning of the facts,” Ed explains. “Then he said the facts had no meaning.” Riedenschneider suggests that someone like “The Barber” could never have conceived not only Tolliver’s murder but Big Dave’s too, nor could such a faceless entity allow Doris to take the rap for his own crime. The jury isn’t convinced, and Ed ends up on death row, writing his story five-cents-a-word for a men’s magazine. (“So you’ll pardon me if sometimes I’ve told you more than you wanted to know,” he says, writing of Cain’s brand of wordy prose.) In the film’s strangest, most mysterious sequence, the night before Ed’s execution he awakens. His cell door is open, and he wanders outside in the courtyard to see a flying saucer hovering, shining a spotlight down on him. He nods, then goes back to his cell. Already there have been multiple references in The Man Who Wasn’t There to UFOs. After Big Dave’s murder and Doris’ arrest, Big Dave’s widow Ann (Katherine Borowitz) appears on Ed’s doorstep, her face trancelike, and tells Ed about a company trip outside of Eugene, Oregon, where Big Dave saw a spacecraft, which took him and performed experiments on him. They reported the incident to the authorities, but Ann says she believes the government or aliens or both are responsible for Big Dave’s death. Later, Ed reads about the Roswell landing in Life magazine, and now seeing or dreaming about a UFO on the eve of his execution, he wonders if there’s something more, some greater meaning or connection to these events. He cannot explain how he got where he is except to trace the events in his cold writing to the men’s magazine. Perhaps UFOs are to blame, or perhaps they represent the Unknown element in Ed’s life—that missing quality in him, which everyone around him seems to have but he, at least outwardly, does not.

What becomes evident is that, despite appearances, Ed believes in something more. He has no idea what that “more” is, but he believes it’s out there. Early on in The Man Who Wasn’t There, before he kills Big Dave, Ed loses himself in contemplation while cutting a Flattop on a boy reading a Dead-Eye Western comic. “This hair, you ever wonder about it?” Ed asks Frank. “How it keeps on coming. It just keeps growing.” Frank, inattentive, “Yeah, lucky for us, huh pal?” Ed, still dour, goes on. “No, I mean it’s growing, it’s part of us. And we cut it off. And we throw it away… I’m gonna take his hair and throw it out in the dirt. I’m gonna mingle it with common house dirt.” Finally Frank wonders, “What the hell are you talking about?” Ed concludes, “I don’t know. Skip it.” Ed has just gone somewhere in his own head and returned, and wherever that was, there’s something weighing on him. He’s not just “The Barber”—he’s capable of abstract thought, and it’s further noticed in the hint of sadness in Ed’s eyes whenever he sweeps up the hair. “Life has dealt me some bum cards,” he admits later on. “Or maybe I just haven’t played ’em right, I don’t know.” But his introspection has transformed the character from a blank, impenetrable slate to someone whose longing is so imprecise, yet so powerful, that we cannot help but view his entire existence as a tragic one, albeit one perpetuated by his own choices.

In that sense, The Man Who Wasn’t There has parallels to Joel and Ethan Coen’s other films about existential uncertainty. Barton Fink (1993), A Serious Man (2009), and Inside Llewyn Davis (2013) each follow a protagonist as they attempt to understand the cruel turns of fate dealt to them, all of which are self-authored by deeply flawed men. But perhaps Ed has more in common with Frances McDormand’s Margie Gunderson in Fargo, the “Minnesota Nice” detective who, after witnessing a man ground up in a woodchipper, asks the killer, “There’s more to life than a little money, you know. Don’tcha know that?” But then resolves that the killing is a shame because “It’s a beautiful day.” Certainly, Ed has even less understanding of his own life than the Dude in The Big Lebowski, whose philosophy “Fuck it, let’s go bowling” is at least consistent, if somewhat meaningless. As for Ed, only in his last hours before his execution does he come to some level of understanding: “I don’t know where I’m being taken,” he says. “I don’t know what waits for me, beyond the earth and sky. But I’m not afraid to go. Maybe the things I don’t understand will be clearer there, like when a fog blows away. Maybe Doris will be there. And maybe there I can tell her… all those things… they don’t have words for here.” Just as the promise of a snow-blind day is beautiful enough for Margie and bowling is enough for the Dude, the hope of something more is enough for Ed. He hasn’t the words or imagination to articulate whatever it might be, but as a man who loves Birdy’s renditions of Beethoven and believes in UFOs, he must feel that something exists out there.

In that sense, The Man Who Wasn’t There has parallels to Joel and Ethan Coen’s other films about existential uncertainty. Barton Fink (1993), A Serious Man (2009), and Inside Llewyn Davis (2013) each follow a protagonist as they attempt to understand the cruel turns of fate dealt to them, all of which are self-authored by deeply flawed men. But perhaps Ed has more in common with Frances McDormand’s Margie Gunderson in Fargo, the “Minnesota Nice” detective who, after witnessing a man ground up in a woodchipper, asks the killer, “There’s more to life than a little money, you know. Don’tcha know that?” But then resolves that the killing is a shame because “It’s a beautiful day.” Certainly, Ed has even less understanding of his own life than the Dude in The Big Lebowski, whose philosophy “Fuck it, let’s go bowling” is at least consistent, if somewhat meaningless. As for Ed, only in his last hours before his execution does he come to some level of understanding: “I don’t know where I’m being taken,” he says. “I don’t know what waits for me, beyond the earth and sky. But I’m not afraid to go. Maybe the things I don’t understand will be clearer there, like when a fog blows away. Maybe Doris will be there. And maybe there I can tell her… all those things… they don’t have words for here.” Just as the promise of a snow-blind day is beautiful enough for Margie and bowling is enough for the Dude, the hope of something more is enough for Ed. He hasn’t the words or imagination to articulate whatever it might be, but as a man who loves Birdy’s renditions of Beethoven and believes in UFOs, he must feel that something exists out there.

The Coens often exaggerate a genre to comic effect, and for The Man Who Wasn’t There, the mechanics of film noir marry with the Coen’s unique brand of searching, and together realize their most mysterious, atmospheric motion picture. Though moments of humor and irony exist in the film, it occupies a distinguished style in artistic expression, whereby the Coens’ chosen genre functions as the only world in which someone like Ed Crane might exist. Film noirs often conclude with the protagonist receiving their overdue comeuppance; such is the case with Ed—but dying doesn’t bother Ed. He doesn’t see much meaning or purpose to this life and thinks there might be something more in the next. Ed’s life has droned along, and he’s barely had a participatory role in his own colorless existence. He has subsisted as The Barber, yet his unpredictably optimistic resolution that something greater might be waiting for him is a curious, fascinating rarity for one of the Coens’ characters. The Man Who Wasn’t There is, therefore, a journey of a man who goes from a certain contentment with purposelessness to, finally, a distinct desire for more. That the film concludes with its protagonist realizing this as he’s executed for murder in the last shot leaves the film strangely tragic and, however uncertainly so, in the end, hopeful.

Bibliography:

Baz Allen, William Rodney, ed. The Coen Brothers: Interviews. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2006.

Bergan, Ronald. The Coen Brothers. New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press, 2000.

Palmer, R. Barton. Joel and Ethan Coen. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004.

Rowell, Erica. The Brothers Grim: The Films of Ethan and Joel Coen. Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2007.

Woods, Paul A., ed, Joel and Ethan Coen: Blood Siblings. London: Plexus, 2000.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review