The Definitives

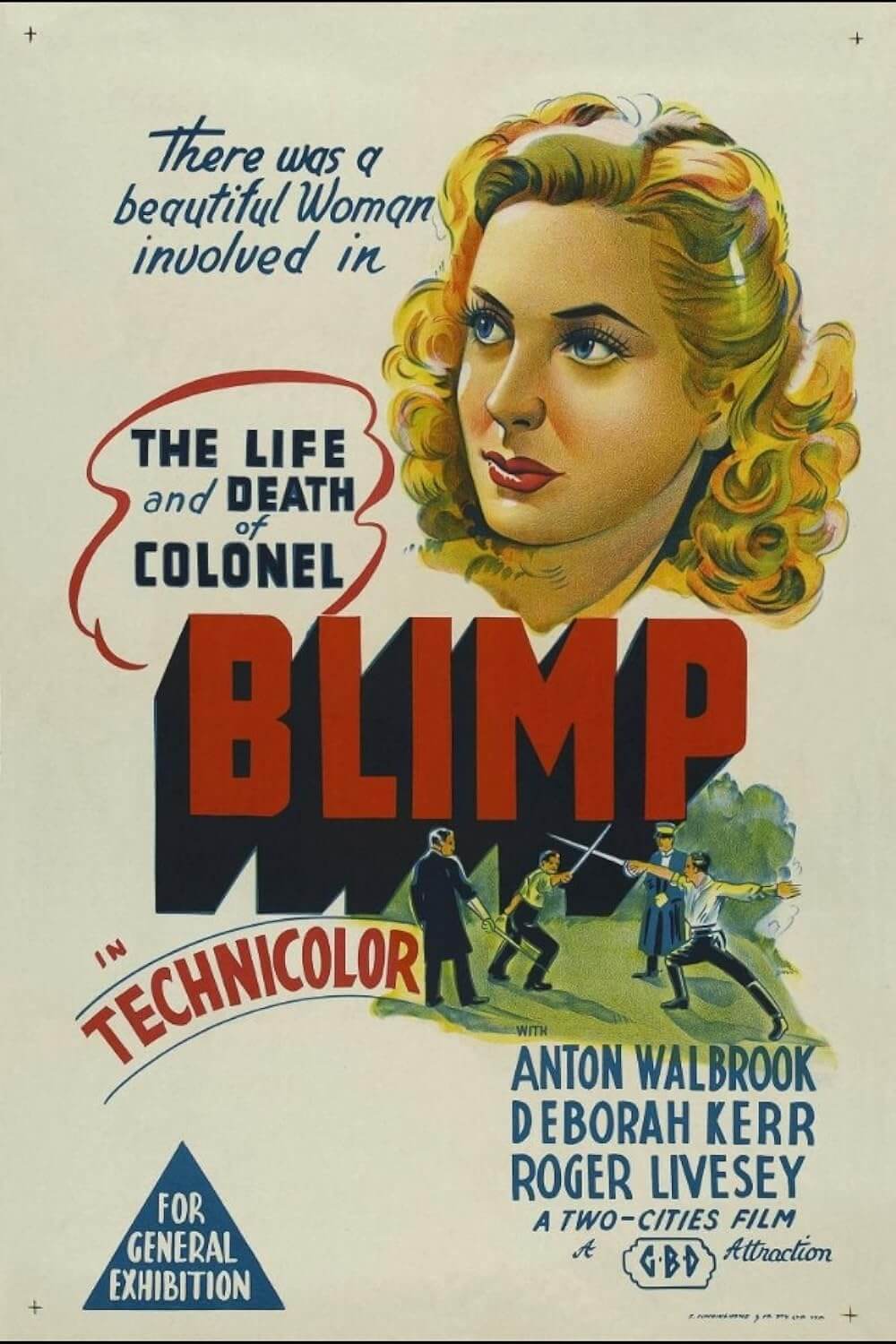

The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

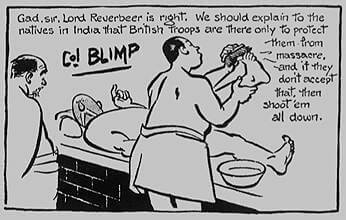

Colonel Blimp began in 1934 as the subject of reactionary British cartoonist David Low. Satirizing stuffy military and political forces from his era, Low’s cartoon ran in London’s Evening Standard, which, through its various sales and syndications, circulated to millions of readers in England and beyond. His cartoons contained a petulant, entitled military hero whose dogmatic perspective on all topics rendered him obsolete, or as Low himself put it, “a symbol of stupidity.” The character defined the type known as blimpish; he often appeared in his Turkish bath wrapped in a towel, barking about this or that issue from his nonsensical and outdated point of view. Through Blimp, Low implied that the leftover officers from the First World War remained pig-headed blowhards who hindered progress against the gangster tactics of the Nazis. From this launching pad, Low’s Blimp character is treated with unlikely compassion by British filmmakers Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, whose 1943 film The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp reformats this caricature of the archaic British establishment into one of the most beloved of all cinematic characters. Powell and Pressburger, jointly known as The Archers, engage romantic ideals in their portrayal of Blimp, thus Britain, though such terms as “romantic” had a negative connotation in their contemporary British society. The stereotyped British film and even Englishman were categorized as dispassionate and heartless from the exterior. But The Archers bore a deep love for Britain, and their film declares that love by dispelling the stereotypes, by representing the most impenetrable satire of the British stiff upper lip with uncharacteristic humanity.

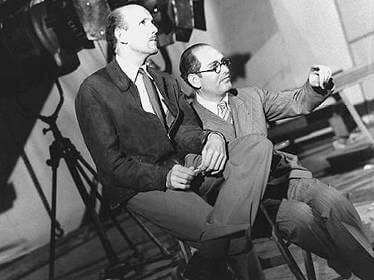

Powell and Pressburger’s partnership began when they were introduced by Hungarian producer Alexander Korda, one of the few major proponents of British film in the Golden Age of Cinema. Silent film director Rex Ingram mentored Powell in acting, editing, screenwriting, and still photography; and Powell practiced his craft during his apprenticeship making quota quickies, four reel short films following the Cinematograph Films Act of 1927. He co-wrote Britain’s first sound film in 1929, Alfred Hitchcock’s Blackmail, and after completing his first picture as director, The Edge of the World in 1937 for American producer Joe Rock, Powell received an invitation to join Alexander Korda’s London Film Production. Korda introduced Powell to Hungarian screenwriter Emeric Pressburger, a violinist and writer who fled Berlin when the Nazis came to power. Powell and Pressburger first collaborated as director and writer respectively on The Spy in Black in 1939, after which Powell co-directed Thief of Bagdad (1940) and The Lion Has Wings (1939) on his own for Korda. Their association resumed in 1940 on Contraband, then 49th Parallel in 1941, and ‘…one of our aircraft is missing’ in 1942. Their success inspired British film mogul J. Arthur Rank to offer Powell and Pressburger their own production company, which they named The Archers, and which Rank would help finance with his recently acquired company General Film Distributors. With independence to pursue whatever projects they desired, and with secure financial backing thanks to Rank, The Archers enjoyed a rare freedom for filmmakers in the 1940s.

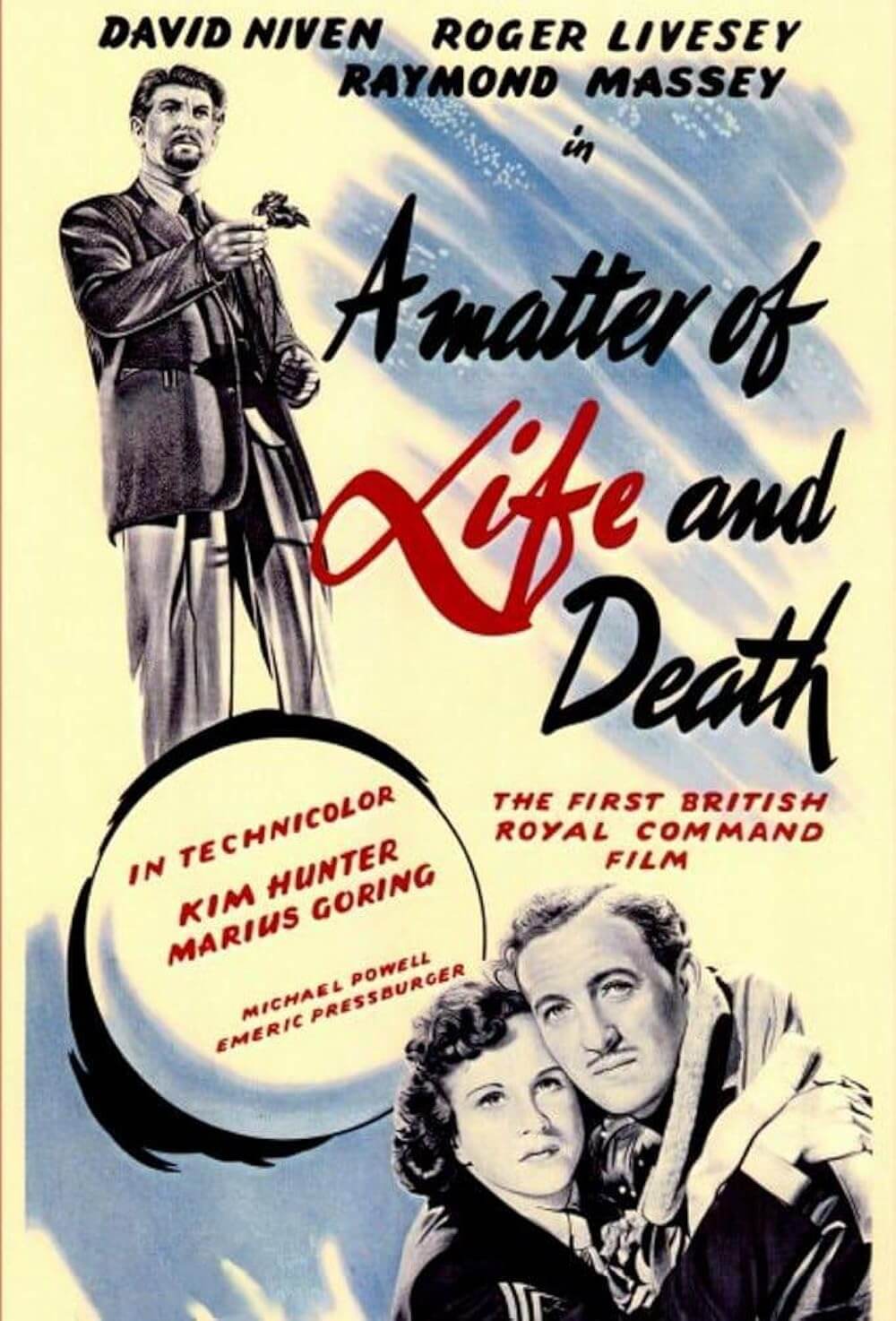

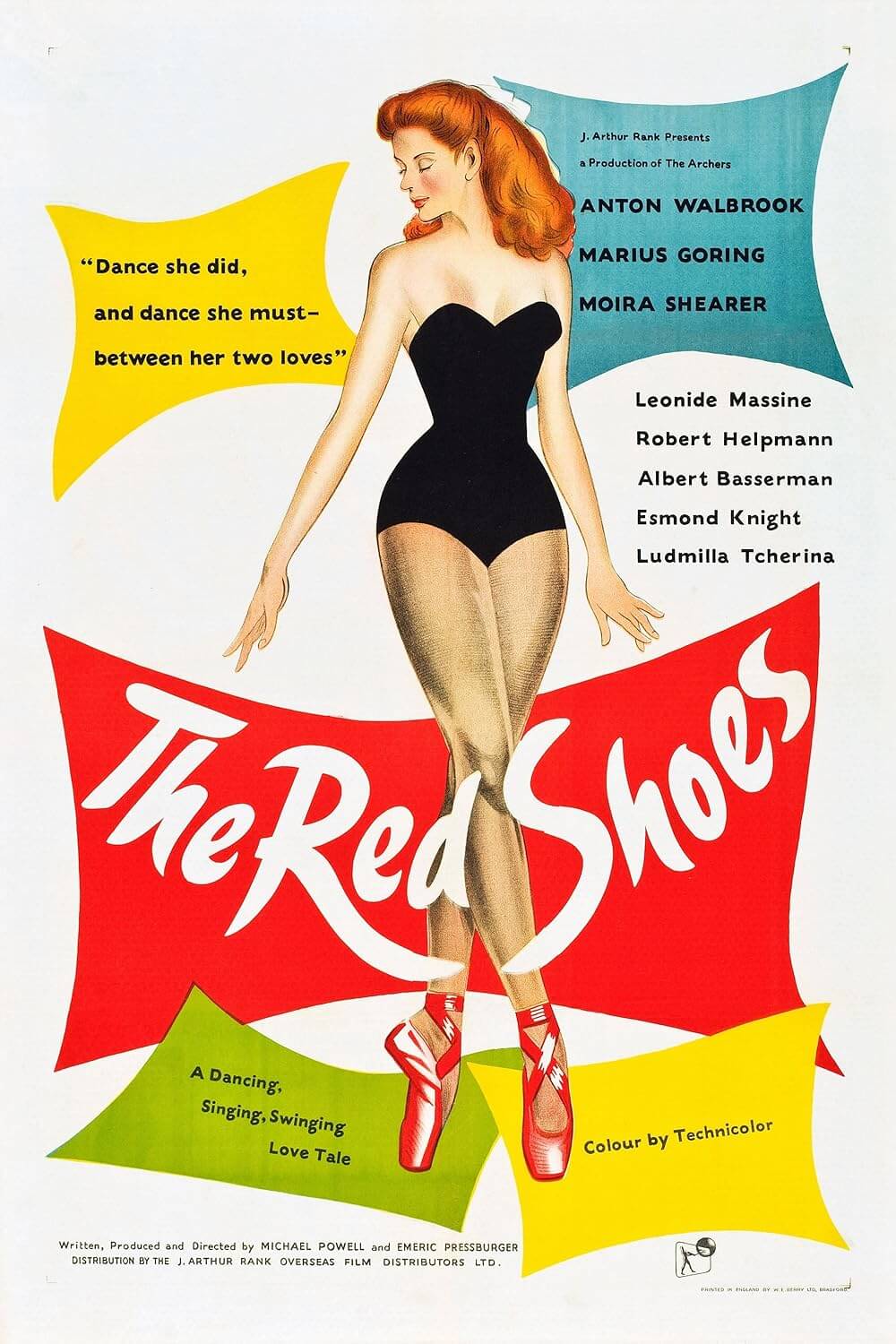

On the margins of British cinema, The Archers were true originals, whereas other filmmakers in the country turned to Hollywood, Germany, and France for inspiration. From their legacy comes treasures like A Matter of Life and Death (1946), Black Narcissus (1947), and The Red Shoes (1948). In a way, The Archers serve as the British equivalent to Stanley Kubrick, in that they were independent filmmakers yet worked within the (British) studio system and, nevertheless, somehow made experimental films. They were outsiders in the cinematic tradition of Orson Welles in that, unlike Kubrick, they were not popular in their time in a commercial sense; and moreover, like Welles, critics misunderstood their output until it was rediscovered long after their productive prime. Over their seventeen-year partnership, it became generally recognized that Pressburger developed their scripts and Powell directed them, yet they shared credit mutually with “written, produced, and directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger” appearing on every film after 1942. Powell was the visual and technical impresario and Pressburger approached narrative with the complexity of a novelist. Powell sought formal ideals rooted in the purest cinematic expression, whereas Pressburger aspired to tell lucid stories with “a little bit of magic.” Their creative union delivered a perfect balance of artistry and craftsmanship.

On the margins of British cinema, The Archers were true originals, whereas other filmmakers in the country turned to Hollywood, Germany, and France for inspiration. From their legacy comes treasures like A Matter of Life and Death (1946), Black Narcissus (1947), and The Red Shoes (1948). In a way, The Archers serve as the British equivalent to Stanley Kubrick, in that they were independent filmmakers yet worked within the (British) studio system and, nevertheless, somehow made experimental films. They were outsiders in the cinematic tradition of Orson Welles in that, unlike Kubrick, they were not popular in their time in a commercial sense; and moreover, like Welles, critics misunderstood their output until it was rediscovered long after their productive prime. Over their seventeen-year partnership, it became generally recognized that Pressburger developed their scripts and Powell directed them, yet they shared credit mutually with “written, produced, and directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger” appearing on every film after 1942. Powell was the visual and technical impresario and Pressburger approached narrative with the complexity of a novelist. Powell sought formal ideals rooted in the purest cinematic expression, whereas Pressburger aspired to tell lucid stories with “a little bit of magic.” Their creative union delivered a perfect balance of artistry and craftsmanship.

Their first picture as The Archers was The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. Shot in Technicolor, the film opens with a rich tapestry depicting the walrus-mustached Blimp in Medieval armor, planes flying overhead and tanks mounting the hill, the character aged and behind the times. Here is the standard Colonel Blimp of David Low’s comic strip, but shown in the form of a textile, a medium that is woven with time and patience—a much more involving design than Low’s black-and-white doodles. In search of understanding their subject’s identity, The Archers dissect Blimp by telling a tale of irony, turning it inside out, looking at the ending’s significance in the beginning, and vice versa. Their target was not bumbling military men; they sought to evoke empathy and compassion for the terminally British character through the insight of time. In doing so, they recognize that Low’s caricature was woefully suspended in his own history; in The Archers’ timeline for the character, Low’s one-dimensional lampoon matures into a tragic figure caged by mores of class and militarist tradition.

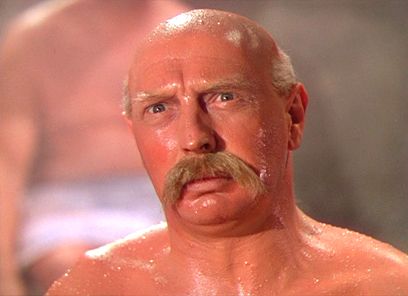

The film’s enduring question: How did a once passionate upstart in the British military, nicknamed ‘Sugar’ Candy, become Major-General Wynne-Candy, a stuffy figure later known for his obstinacy? In the present London of 1942, Candy, played in an uncanny transformation by Roger Livesey, finds himself caught unawares during a Home Guard exercise. The war game was to begin at midnight, but the modern counterpart of Candy’s younger self, Spud Wilson (James McKechnie), opts to begin six hours earlier, calling his scheme equivalent to the dirty methods of the Nazis. Candy, appearing as he does in many of Low’s cartoons, wrapped in a towel in a Turkish bath, endures insults from the impudent Wilson for the size of his stomach, for his thick mustache, and for obeying “national sporting club” rules of war. Enraged, Candy swings at Wilson announcing, “You laugh at my big belly, but you don’t know how I got it. You laugh at my mustache, but you don’t know why I grew it. How do you know what sort of fella I was when I was as young as you are, forty years ago?”

During the fracas, Candy submerges into the bath, and his past, with the ponderings of how he became an aged officer, soon surface as if cleaned by a baptismal experience of memory. The film bridges the gap between the paradox of youth being unable to imagine themselves old, and the aged forgetting what it was like to be young. Time represents a longing for what has been lost, be it love, youth, or the traditionalism that faded after the First World War. Time stops as Candy is arrested during the war game exercise so that he may contemplate his earlier years by being plunged into the past. His memories tell a story and trace a timeline, in which the audience closely follows over the expanse of the film, leaving the viewer no choice but to identify with Candy as his blimpish front dissolves with his growing permanence as the protagonist.

During the fracas, Candy submerges into the bath, and his past, with the ponderings of how he became an aged officer, soon surface as if cleaned by a baptismal experience of memory. The film bridges the gap between the paradox of youth being unable to imagine themselves old, and the aged forgetting what it was like to be young. Time represents a longing for what has been lost, be it love, youth, or the traditionalism that faded after the First World War. Time stops as Candy is arrested during the war game exercise so that he may contemplate his earlier years by being plunged into the past. His memories tell a story and trace a timeline, in which the audience closely follows over the expanse of the film, leaving the viewer no choice but to identify with Candy as his blimpish front dissolves with his growing permanence as the protagonist.

In a fluid transition and unbroken shot, Major-General Wynne-Candy lunges into the bath with Spud Wilson and comes out the other side a young man. The year is now 1902, and ‘Sugar’ Candy appears lean, clean-shaven, and full of enterprising ideas and humor. The off-duty soldier’s boldness takes him to Germany where he defends the honor of the politically minded Edith (Deborah Kerr), landing himself in a duel against German soldier Theo Kretschmar-Schuldorff (Anton Walbrook). The sparring leaves Candy scarred on the upper lip, inspiring him to grow his walrus mustache to cover the mark. While recovering in hospital, Candy turns his rival Theo into the oldest of friends, and he watches as his deepest love and romantic ideal, Edith, passes him by and marries Theo instead. And so, Candy forgoes love and instead busies himself with soldiering and hunting—gunshots ring out as mounted heads from safari appear on the wall in his study—only to discover a wife in a World War I nurse, Barbara (also played by Kerr), the spitting image of his ideal. Approaching the present, Candy’s wife has passed on, and over time he rekindles his friendship with Theo and hires a personal military driver, Angela ‘Johnny’ Cannon (Kerr again), another replica of Edith. With the onset of World War II, the aged Candy receives notice of termination from the military. His life of service leaves him useless when he’s barred from fighting a war, so he spearheads the Home Guard initiative to protect English soil, a task that represents his sole hope of having some purpose in his old age.

The sweeping Technicolor presents The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp as a dramatic epic of passions over battles. The achievement of the Archers’ schema can be measured by the profound change in how the audience feels toward Candy when he is captured by Spud, to how our feelings about him change and deepen by the finale. When surprised and taken by Spud in the film’s opening sequence, Candy appears as nothing more than David Low’s cartoon character, bombastic and irascible. This moment comes from the outlook of the youthful soldiers, set to a playful jazzy tune that reflects their improvised military tactics. Later, after Candy’s story has been told, Spud’s victory arrives with a sting, as the film’s perspective has shifted to Candy. By Spud innovating in the military training exercise, he proves Candy obsolete militarily, delivering a heartbreaking dramatic truth that with time all things fade.

In youth, Candy boasts the same qualities of the blustering young soldiers who take him hostage as an older man, but because time has run its course, leaving marks of disappointment and regret upon his mind, he has become a “blimpish” character who refuses change. Of course, the film insists that no one could ever fully digress into a blimpish character; some humanity exists even in the most caricatured blimps. Candy’s conservatism allows the young soldiers to get the better of him; moreover, The Archers suggest that while old-fashioned virtues open one up to more ruthless enemies, like Adolf Hitler, such virtues are ingrained into the British spirit. In other words, British conventionalism can be dangerous but it also builds character. Candy’s ways are obsolete when facing an inhuman enemy, which demands change in military orthodoxy and hierarchy, except the type of dignity projected by Candy’s type also fades with these new enemies, which itself is tragic.

In youth, Candy boasts the same qualities of the blustering young soldiers who take him hostage as an older man, but because time has run its course, leaving marks of disappointment and regret upon his mind, he has become a “blimpish” character who refuses change. Of course, the film insists that no one could ever fully digress into a blimpish character; some humanity exists even in the most caricatured blimps. Candy’s conservatism allows the young soldiers to get the better of him; moreover, The Archers suggest that while old-fashioned virtues open one up to more ruthless enemies, like Adolf Hitler, such virtues are ingrained into the British spirit. In other words, British conventionalism can be dangerous but it also builds character. Candy’s ways are obsolete when facing an inhuman enemy, which demands change in military orthodoxy and hierarchy, except the type of dignity projected by Candy’s type also fades with these new enemies, which itself is tragic.

Candy’s humanity finds its home in the roles played by Deborah Kerr, a repeating element which reveals not only that Candy seeks ideals both in his militarism and his women, but also calls attention to the changing roles in women over time. From the mannered and politically inclined governess Edith, to the ever-supportive wife in Barbara, to the utilitarian feminist Angela who insists on being called “Johnny,” Kerr’s roles distinctly identify that Candy’s ideal remains rooted in the past, and so he too refuses to look forward and change. Kerr’s performances remain so dissimilar from one another that a viewer unfamiliar with her might assume the roles were achieved by different actresses. Only Livesey surpasses her in his onscreen transformation, embodying the temporally altered personas of Candy as he grows old, swells, and metamorphoses from a lean soldier to the inflated stuff of Low’s cartoons.

The other decisive figure in Candy’s life, his German friend Theo Kretschmar-Schuldorff, played with poignant sincerity by Walbrook, further emphasizes Candy’s inability to progress. Just after World War I has ended, Candy invites the captured German soldier Theo to a stately bachelor party dinner with his British military friends, but he cannot comprehend that his German mate might find dining with the former enemy socially awkward. The war is over, and Candy expects all grudges dropped as though a switch was flipped. This moment recalls Candy arguing with Spud Wilson—“But war starts at midnight!”—unable to see beyond his devotion to the rules of war. Only years later when World War II breaks out does Theo return to Britain, the home of his wife Edith, who has since died. He explains that because his homeland now seems foreign to him with the rise of Fascism, he has arrived in Britain to feel some lingering notion of home, via his wife’s native soil. The curious friendship between Candy and Theo offers a parallel for Powell and Pressburger, respectively. Candy signifies Powell’s very British persona, as in the past Powell has admitted his staunch Britishness with shame, mindful of the drawbacks to British tenets but ever devoted to their idiosyncrasies. Meanwhile, Theo mirrors Pressburger, the migrant forced into a life of exile, whose address is British because his home has become overrun by villains.

As a criticism of staunch militarism, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp does exact its lashings; however, it’s more effective as a demonstration of why the contemporary officer class was ill-equipped to handle the unpredictable threat of Nazi Germany, whereas younger soldiers willing to adapt could better handle the new enemy. Through the drama of the film, The Archers suggest this truth is a heartbreaking one, as officers whose entire lives were dedicated to the military were now out of touch with their occupations. In another sense, Powell and Pressburger acknowledge that those officers are at fault by allowing themselves to fall into the traps of their lives; men such as Candy show reluctance to look outside of traditionalism, set their eyes to the past, and ignore the burgeoning modernity around them. And yet, The Archers are hopeful, for they allow Candy to change in the finale by recognizing the folly of his past and realizing what he has become. Perhaps this epiphany serves as an example for the blimps present in the British military during the film’s release, suggesting that identity is not equivalent to ideals but rather a construct formed over time, built upon and ever incomplete. Indeed, the film strives to demonstrate how both old soldiers and new work toward the same goal; the only outsider in the situation remains the Nazi villains.

As a criticism of staunch militarism, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp does exact its lashings; however, it’s more effective as a demonstration of why the contemporary officer class was ill-equipped to handle the unpredictable threat of Nazi Germany, whereas younger soldiers willing to adapt could better handle the new enemy. Through the drama of the film, The Archers suggest this truth is a heartbreaking one, as officers whose entire lives were dedicated to the military were now out of touch with their occupations. In another sense, Powell and Pressburger acknowledge that those officers are at fault by allowing themselves to fall into the traps of their lives; men such as Candy show reluctance to look outside of traditionalism, set their eyes to the past, and ignore the burgeoning modernity around them. And yet, The Archers are hopeful, for they allow Candy to change in the finale by recognizing the folly of his past and realizing what he has become. Perhaps this epiphany serves as an example for the blimps present in the British military during the film’s release, suggesting that identity is not equivalent to ideals but rather a construct formed over time, built upon and ever incomplete. Indeed, the film strives to demonstrate how both old soldiers and new work toward the same goal; the only outsider in the situation remains the Nazi villains.

In structure, the film bears a close resemblance to Citizen Kane (1941), although no upfront or public mystery exists in the film that deems an investigation (e.g. What is ‘Rosebud’?). The queries into the past are an existential investigation by a party that is objective to his own story. As Candy reflects on his life, his earliest tales are subjective and romantic, whereas with age the subjectivity of the protagonist dissipates, as, increasingly, he becomes seen as the blimpish character captured by Spud Wilson. By the ending, however, the tragedy is apparent with Candy’s remembrance complete. Candy once again becomes the subject by giving the audience a complete view of his life; the film then allows that perspective to diffuse any perception of the character as blimpish. Much like Citizen Kane does, the film edifies the audience through a process of building, and only by the last moments can we fully grasp the sweeping tragedies of the life on trial.

The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp was shot for under a million dollars in four months in Denham Studios, around the bomb-riddled section of London, and on the English countryside, all in the midst of the raging World War II. As a result of the production’s purported criticism of the military class, The War Office refused to cooperate with the production, going as far as denying Powell and Pressburger access to their proposed star, Laurence Olivier, by not releasing the actor from his Fleet Air Arm service. Winston Churchill himself caught wind of the production’s intentions and attempted to shut it down for its reported antagonism toward the British militaristic tradition, which he believed would do harm to the country. Although, Churchill likely opposed the material because he saw himself as a blimpish character and therefore attributed the film to a personal attack. But The Archers hardly paint their subject in a negative light. If Candy was really a mockup of Churchill, then Powell and Pressburger honored their Prime Minister, as the film serves to humanize the figure. Certainly, Candy proves to be an assemblage of labels, but his characterization contains such incredible pathos, thanks largely to Roger Livesey’s affecting performance, that it remains impossible to limit the film’s range to a mere satire of Churchill.

Theaters advertised Churchill’s disapproval of the production, announcing that audiences should rush to see the sure-to-be-banned film while they can. Meanwhile, the Sidneyan Society, a group that hunted down signs of pro-German signifiers in British cinema, released the pamphlet The Shame and Disgrace of Colonel Blimp, which accused the film of pro-Nazi undercurrents. While true that the film represents a sympathetic German in Theo, even critics at the time did not consider the film anti-British, rather just confusing in terms of its intentions. Released in 1943, the film received favorable reviews, but did not reach the United Stated until 1945 because of Churchill’s disapproval, and only then after unfortunate edits. The most widespread comment found when reading through the original reviews is something akin to ‘But what does it mean?’

Theaters advertised Churchill’s disapproval of the production, announcing that audiences should rush to see the sure-to-be-banned film while they can. Meanwhile, the Sidneyan Society, a group that hunted down signs of pro-German signifiers in British cinema, released the pamphlet The Shame and Disgrace of Colonel Blimp, which accused the film of pro-Nazi undercurrents. While true that the film represents a sympathetic German in Theo, even critics at the time did not consider the film anti-British, rather just confusing in terms of its intentions. Released in 1943, the film received favorable reviews, but did not reach the United Stated until 1945 because of Churchill’s disapproval, and only then after unfortunate edits. The most widespread comment found when reading through the original reviews is something akin to ‘But what does it mean?’

Audiences and critics alike had grown accustomed to films of the period, especially those with military characters, having propagandistic intentions. Wartime films resting on the idea that “films must be good entertainment if they are to be good propaganda” almost always contained obligatory propaganda themes. Powell and Pressburger’s 1941 release 49th Parallel, for example, concerned Nazi invaders trekking across the British-sympathetic Canada into America, where the filmmakers hoped their message would resonate most and encourage U.S. audiences to join the war. However The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp was filmed without portentous political undercurrents; it instead rests on romantic ideals, which surely would have seemed strange and uncharacteristic in a time of nationalist rallying. Candy sees images of the characters played by Kerr repeated throughout his history and feels severe regret, leaving an audience with the impression that war and a lifetime of military service have inherent sacrifices. But the entire story comes from an ironic cinematic voice that has no desire to represent realism (rather sardonic images of animal heads materializing on a wall set to the sound of gunfire), so extracting a political or anti-Britain message from this humanist film proves to be a clumsy reading.

The use of Technicolor in the film, shot by cinematographer Georges Périnal with the assistance of The Archers’ longtime collaborator Jack Cardiff, exaggerates any sentiment of realism and reminds the viewer of the film’s poetic approach. The dreamy quality of the narrative, leaping back through time to investigate the life of one man, requires a painterly use of expressive colors to lend a sense of magic. Had the film been shot in black-and-white, the same significance could not be recognized scene after scene in consideration of the film’s otherworldly movement through time. It was the first of many glorious and increasingly inventive applications of the Technicolor device throughout Powell and Pressburger’s career, followed by A Matter of Life and Death, Black Narcissus, The Red Shoes, and The Tales of Hoffman. In each case, the filmmakers resisted the customary supervising technicians from Technicolor and experimented with the medium with their photographer, exploring high contrasts in a varied palette that brings added emotional meaning and artistic wonder to every scene.

Having proved confusing for audiences unfamiliar with Low’s cartoons, exporting the film became a question of how much of the runtime would be cut to make the picture suitable for non-British audiences. Cuts were made because audiences abroad proved baffled by the material, because the film was deemed tedious, or because of a reported shortage of Technicolor film stock. Whatever the excuse, the first U.S. release was cut by ten minutes, and then it was trimmed to a brisk 93 minutes, a version that seems impossible now when viewing the nearly three-hour picture in its entirety. For years, the abridged print circulated and, regardless of its brevity, inspired 1970s-era cineastes, newly intrigued by the auteur theory, to seek out the work of the little-known producing, writing, and directing team of The Archers. Their lack of single authorship may not have met the requirements of an auteur, but the films from Powell and Pressburger contain an undeniable relativity in terms of their power and mysticism. Only after this belated interest did a restored print of The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp find its way to the screen in 1985, establishing its place in the canon of great motion pictures.

For the film’s contemporary critics, the most powerful of them Churchill, the question of the film’s intentions remained. But if The Archers did not love their country, why would Blimp ask, “What are we fighting for if not home?” Theirs was not a blind love, however. The Archer’s logo—a red, white, and blue target pierced by the golden arrow—stood for the filmmaker’s undeniable mark on British cinema, their national pride combined with their need to confront crucial problems in modern society. Theirs is a nationalistic cinema without being wholly conservative or dogmatic (or commercial) about its values. Throughout their entire career, The Archers allowed influence from international sources (such as returning actors Anton Walbrook and Conrad Veidt, cinematographers Erwin Hillier and Georges Périnal, and designers Alfred Junge and Hein Heckroth) to create a uniquely British cinema. Deriving style from French, Italian, and particularly German cinema was a time-honored tradition in British films, and also a major criticism, because it left British cinema without a singular national identity. Powell and Pressburger adopt influence from international sources like their contemporaries, but they dedicate themselves to pointedly British characters as their subjects, portraying Britain with both love and acceptance of her follies in the most indiscriminate way possible.

For the film’s contemporary critics, the most powerful of them Churchill, the question of the film’s intentions remained. But if The Archers did not love their country, why would Blimp ask, “What are we fighting for if not home?” Theirs was not a blind love, however. The Archer’s logo—a red, white, and blue target pierced by the golden arrow—stood for the filmmaker’s undeniable mark on British cinema, their national pride combined with their need to confront crucial problems in modern society. Theirs is a nationalistic cinema without being wholly conservative or dogmatic (or commercial) about its values. Throughout their entire career, The Archers allowed influence from international sources (such as returning actors Anton Walbrook and Conrad Veidt, cinematographers Erwin Hillier and Georges Périnal, and designers Alfred Junge and Hein Heckroth) to create a uniquely British cinema. Deriving style from French, Italian, and particularly German cinema was a time-honored tradition in British films, and also a major criticism, because it left British cinema without a singular national identity. Powell and Pressburger adopt influence from international sources like their contemporaries, but they dedicate themselves to pointedly British characters as their subjects, portraying Britain with both love and acceptance of her follies in the most indiscriminate way possible.

Though their critiques of British shortcomings were evident in their films, Powell and Pressburger never overstepped their bounds during their partnership. They tiptoed on the edge in such a way that proved strangely harmonious, enough to earn them, at first, neither a far-reaching respect among the British nor a complete rejection. The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp may have been met with confusion and raised eyebrows, but as time passed, and as the British stereotype of being an emotionally wooden populace waned, so too did the audience’s puzzled suspicion toward Powell and Pressburger’s work. And while the filmmakers avoided offending British sensibilities outright during their partnership, the marked consonance of their affiliation became unchecked when the two men separated. After the filmmakers ended their partnership in 1957, Pressburger went on to unremarkable fare, whereas Powell, unrestrained by his partner’s temperance, lashed out in the 1960s with his aggressive ode to the horrors of film-making, Peeping Tom (1960), and his provocative exploration of sexual desire and artistic creation, Age of Consent (1969).

Only together could Powell and Pressburger create such a balanced and visionary body of work, its bounds and sophistication matched only by its boldness and passion, qualities rare to Britain’s otherwise inexpressive cinematic persona. In The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, those qualities reach a height of narrative scope and formal splendor. Exploring Major-General Wynne-Candy’s identity, The Archers consider the protagonist with elegance and dramatic gravity, and in turn, they humanize David Low’s Colonel Blimp in ways seemingly not possible. Never does the film suggest, as the reactionary Low or naïve soldier Spud Wilson do, that a polarized ideological shift suddenly one day transformed Candy from a young bravado to a stuffy officer; through an expansive survey of Candy’s life, always cognizant of the passing of time, the change is depicted in both satirical and tragic terms with humanist reflection. Powell and Pressburger’s romantic and sophisticated approach underscores how unique The Archers were for their buoyancy and emotional lucidity, long before British cinema developed such virtues.

Bibliography:

Christie, Ian. Arrows of Desire: The Films of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. Faber & Faber, 1994.

Christie, Ian. Powell, Pressburger and Others. BFI (British Film Institute), 1978.

Christie, Ian and Moor, Andrew, eds. The Cinema of Michael Powell. BFI (British Film Institute), 2005.

Moor, Andrew. Powell and Pressburger: A Cinema of Magic Spaces (Cinema and Society). I.B. Tauris; Distributed in the U.S. by Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

Powell, Michael. A Life In Movies: An Autobiography. Heinemann, 1986.

Powell, Michael. Million Dollar Movie. Heinemann, 1992.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review