The Definitives

The Lady Eve (1941)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Compare today’s average romantic comedy to the work of the genre’s most celebrated practitioner, Preston Sturges, and it becomes tragically clear that something crucial has been lost in the genre over time: The ability to innovate within convention. Hollywood has all but exhausted its novel ideas about the romantic comedy, and the methods with which modern filmmakers use to explore falling in love have become commonplace, dull, and repetitive. And falling in love should be anything but. Still, the tradition of mechanical, by-the-numbers romantic comedies has existed almost as long as the genre itself. But story originality is not the concern here. The approach to the material, the technique in which the story is told, from the flourishes in the dialogue used to the nature of the characters, remains the ever-maltreated element in modern romantic comedies, and the deficient source of their rapidly dwindling appeal. Whenever a great romantic comedy comes along, it should be propped up and celebrated as a rare thing, because they do not come along often. And yet, Preston Sturges made several of them. The best of them is The Lady Eve. By the year of its release in 1941, romantic comedy convention had been well established; however, the film serves as a grand lesson to any filmmaker posed with the question of how to approach the genre’s formulas. Its plot has been sewn together by formula. But the finesse, intelligence, and innovation that Sturges commands in his treatment is what helped establish his ideas as formulas in the first place.

Sturges had completed is original screenplay for The Lady Eve in 1938, two years before his debut year as director in 1940. Sturges was a relatively fresh face on the Hollywood scene, graduating from accomplished writer to celebrated director virtually overnight. In 1940, he made his directing debut with The Great McGinty and followed it three months later with Christmas in July, both huge successes. Originally titled Two Bad Hats, Sturges loosely based his screenplay for the Lady Eve on Monckton Hoffe’s original short story and kept only a few ideas established in that text; among them, he maintained the notion of riverboat gambling ship and a father-daughter gambling team. Sturges intended the project for producer Al Lewin and star Claudette Colbert, but that production never came to fruition. Once he proved himself as a director, Sturges developed the picture for himself at his then-home studio, Paramount Pictures. He lined up Madeleine Carroll to star opposite either Joel McCrea, or possibly Fred MacMurray. And when those names fell through, he sought out Barbara Stanwyck, whose reputation as a true professional had long interested the new director. Years before, he promised to write a great comedy role for her. “I told him that I never get great comedies,” she remembered. At this, Sturges replied confidently, “Well, you’re going to get one.” For his leading man, Sturges had only Henry Fonda in mind and refused to consider any alternative, but Fonda was contracted to Fox. Producer Y. Frank Freeman worked out a deal with Darryl Zannuck to use Fonda in exchange for a lump sum, as well as Sturges’ services on a future project.

Filming began on October 12, 1940, and Paramount Pictures granted Sturges considerable freedom, given he had only two films under his belt. Fortunately, the studios trusted Sturges. The press called him “boy wonder” and “whiz kid” and other such nomenclatures. The box-office performance of his film two films was only matched by how evenly he catered to the needs of both the studios and general audiences. To be sure, Sturges catered with a particular insight and ingenuity that survives as his signature. For much of his early career heyday, which lasted a shockingly brief period from 1940-1944, he maintained considerable creative control while working within the established guidelines of a major studio. The press, fascinated by this bona fide genius and inventor of gadgets—someone the studio’s publicity department was happy to saddle with a “wunderkind” label—sent The Saturday Evening Post’s writer Alva Johnston to write a two-part profile to be published in conjunction with The Lady Eve‘s release. Sturges did not mind the attention. Unlike other directors, he welcomed the press on his sets—he invited them. Sturges thrived on commotion. His sets were welcomed places for people who had no need to be there. Visitors were greeted graciously. He hired the piano tuner, Harry Rosenthal, to play between takes. The radio blared and the behind-the-scenes crew would talk. It may have seemed like chaos, but all the while Sturges would plan his next scene, dictate more dialogue, and sometimes fiddle with whatever invention he had been tinkering with. Quite appropriately, he saw the process of filmmaking as a group activity. After each day of shooting, he forced his cast and crew to sit back and watch their day’s work, the rushes that demonstrated how clear it was that Sturges had complete control.

Filming began on October 12, 1940, and Paramount Pictures granted Sturges considerable freedom, given he had only two films under his belt. Fortunately, the studios trusted Sturges. The press called him “boy wonder” and “whiz kid” and other such nomenclatures. The box-office performance of his film two films was only matched by how evenly he catered to the needs of both the studios and general audiences. To be sure, Sturges catered with a particular insight and ingenuity that survives as his signature. For much of his early career heyday, which lasted a shockingly brief period from 1940-1944, he maintained considerable creative control while working within the established guidelines of a major studio. The press, fascinated by this bona fide genius and inventor of gadgets—someone the studio’s publicity department was happy to saddle with a “wunderkind” label—sent The Saturday Evening Post’s writer Alva Johnston to write a two-part profile to be published in conjunction with The Lady Eve‘s release. Sturges did not mind the attention. Unlike other directors, he welcomed the press on his sets—he invited them. Sturges thrived on commotion. His sets were welcomed places for people who had no need to be there. Visitors were greeted graciously. He hired the piano tuner, Harry Rosenthal, to play between takes. The radio blared and the behind-the-scenes crew would talk. It may have seemed like chaos, but all the while Sturges would plan his next scene, dictate more dialogue, and sometimes fiddle with whatever invention he had been tinkering with. Quite appropriately, he saw the process of filmmaking as a group activity. After each day of shooting, he forced his cast and crew to sit back and watch their day’s work, the rushes that demonstrated how clear it was that Sturges had complete control.

Production wrapped in 41 days under Sturges’ confident direction. Though he had no formal training as a filmmaker, Sturges had had a definite understanding of film theory and a “formulated and sophisticated understanding of film drama”. He also had a complete understanding of both formal technique and a moviegoer’s needs, much like the very best directors of such well-timed comedies. “What I learned I picked up on sets,” he once explained. “I just kept my eyes opened and learned.” Sturges must have learned a lot; his timing is pitch-perfect. No comedy director outside of Ernst Lubitsch and Howard Hawks delivered sharper, snappier dialogue in such a precise, rapid-fire tempo. The speed and volume of every line delivery was labored over on the set, and better yet Stanwyck could deliver each line perfectly. She understood Sturges’ style down to her bones. Indeed, the actress and her director formed an immediate professional understanding. “I think there was a great compatible feeling between Sturges and myself,” she remembered. “The performer can’t work miracles,” she remarked of Sturges’ script. “If it isn’t [in the script], it isn’t on the screen.” Of his script, Sturges once remarked that he intended no moral to The Lady Eve; he wanted only to tell an amusing story. And even though Sturges was merely trying to entertain audiences with The Lady Eve, he also sought to strike out at the critics who labeled him a “genius” because of his earlier films. He did so by delivering a formulaic story, but a damn good one.

The Lady Eve opens on a cruise ship on the Amazon River. Twists and turns along the way make a rather common tale about one lover forgiving the other’s past seem fresh and new even today. Up the river for a year on a scientific exploration, Charles Pike (Henry Fonda), the famed son of an ale mogul, ends his expedition and joins the passengers on a gambling ship returning to the States. Charles looks naïve, being more interested in snakes than in women or business, and his naivety is spotted at once by a father-daughter duo of card sharks. In Charles, ‘Colonel’ Harry Harrington (Charles Coburn) and his daughter Jean (Barbara Stanwyck) see yet another in a long line of Jean’s would-be suitors from whom they can swindle their loot. As Charles climbs up the ladder to the ship, Jean drops an apple on his pith helmet, a devilish replacement for Cupid’s arrow. That evening in the ship’s restaurant, Jean watches the bookish Charles through her makeup mirror and narrates to herself, offering a play-by-play of the other women in the restaurant vying for Charles’ attention, while he simply reads his Are Snakes Necessary? text. The scene demonstrates Jean’s absolute control over and assessment of Charles, rendering him powerless. Various women try to draw Charles’ gaze by dropping their handkerchief or pretending to know him from somewhere, but none of them are successful. Jean does the opposite. She trips him, breaking her high heel in the process. Etiquette dictates that Charles should escort the lady back to her room to fetch another pair of shoes. In her cabin, the stiff Charles, having been up the river for a year, is suddenly drunk with attraction, enamored by Jean, her perfume, and the ways she gets close and plays with his hair.

The Lady Eve opens on a cruise ship on the Amazon River. Twists and turns along the way make a rather common tale about one lover forgiving the other’s past seem fresh and new even today. Up the river for a year on a scientific exploration, Charles Pike (Henry Fonda), the famed son of an ale mogul, ends his expedition and joins the passengers on a gambling ship returning to the States. Charles looks naïve, being more interested in snakes than in women or business, and his naivety is spotted at once by a father-daughter duo of card sharks. In Charles, ‘Colonel’ Harry Harrington (Charles Coburn) and his daughter Jean (Barbara Stanwyck) see yet another in a long line of Jean’s would-be suitors from whom they can swindle their loot. As Charles climbs up the ladder to the ship, Jean drops an apple on his pith helmet, a devilish replacement for Cupid’s arrow. That evening in the ship’s restaurant, Jean watches the bookish Charles through her makeup mirror and narrates to herself, offering a play-by-play of the other women in the restaurant vying for Charles’ attention, while he simply reads his Are Snakes Necessary? text. The scene demonstrates Jean’s absolute control over and assessment of Charles, rendering him powerless. Various women try to draw Charles’ gaze by dropping their handkerchief or pretending to know him from somewhere, but none of them are successful. Jean does the opposite. She trips him, breaking her high heel in the process. Etiquette dictates that Charles should escort the lady back to her room to fetch another pair of shoes. In her cabin, the stiff Charles, having been up the river for a year, is suddenly drunk with attraction, enamored by Jean, her perfume, and the ways she gets close and plays with his hair.

Stanwyck is irresistibly sexy in a scene where, her deep voice speaking Sturges’ dialogue, she reclines back on her shoe case and asks Charles, “See anything you like?” Stanwyck, in one of her greatest performances, plays a familiar trope, the Camille-type whose practiced sexuality is nevertheless seduced by the virginal innocence of a naïve man—someone all the more appealing because he represents an antithesis to her line of work. At the same time, she embodies a strong symbol of feminine sexual control and a sympathetic woman, susceptible to love. Stanwyck often played strong women with a vulnerable streak and almost never the damsel in distress. Watch how sexy, yet complex she manages to be in The Lady Eve as she smiles knowingly over Charles, sure in the knowledge that she owns him, yet also defenseless to his awkward charm. It takes a special kind of actress to evoke such a complicated array of feeling in a single expression. Indeed, though Jean had intended to empty Charles’ checking account over several nights of friendly card games with her father, she falls for his simplicity just as he falls for her directness. Soon engaged, Jean is ready to leave behind her life as a con artist. But the suspicions of Charles’ valet, the wonderfully named Muggsy Murgatroyd (Sturges favorite William Demarest), expose the notorious identities of Jean and her father. Despite his love, Charles inflexibly calls off the marriage and they go their separate ways, he stubborn and unwilling to forgive, she heartbroken and hungry for revenge.

Some time later, Charles is yet again falling for Jean in his own home, but this time she has concocted an elaborate scheme to make him believe she is someone else. Charles looks dumbfounded at the sight of Jean in a thinly veiled disguise as Great Britain’s The Lady Eve Sidwich, the supposed niece of Sir Alfred McGlennan Keith (Eric Blore), another con artist who has planted himself among New England elite and agreed to help Jean get back at Charles. At a posh party hosted by Charles’ father, Horace Pike (Eugene Pallette), Jean fronts herself as The Lady Eve and the guests circle around her and listen to her false stories about acclimating to the Unites States. Charles cannot be sure if this is the same woman, but Sir Alfred puts his doubts to rest through an absurd story about a coachman, a scandalous pregnancy, twin daughters, and divorce. Resigned to the idea that The Lady Eve is the twin sister of Jean Harrington, Charles is quickly duped into marriage. However, Jean gets her revenge when, on their honeymoon, knowing Charles is the old-fashioned type, he demands a divorce after Eve confesses to a string of past lovers. Jean’s plot to secure herself a hunk of the Pike fortune in a messy divorce has succeeded. But rather than a sense of victory, Jean feels sadness. She does love Charles after all.

Some time later, Charles is yet again falling for Jean in his own home, but this time she has concocted an elaborate scheme to make him believe she is someone else. Charles looks dumbfounded at the sight of Jean in a thinly veiled disguise as Great Britain’s The Lady Eve Sidwich, the supposed niece of Sir Alfred McGlennan Keith (Eric Blore), another con artist who has planted himself among New England elite and agreed to help Jean get back at Charles. At a posh party hosted by Charles’ father, Horace Pike (Eugene Pallette), Jean fronts herself as The Lady Eve and the guests circle around her and listen to her false stories about acclimating to the Unites States. Charles cannot be sure if this is the same woman, but Sir Alfred puts his doubts to rest through an absurd story about a coachman, a scandalous pregnancy, twin daughters, and divorce. Resigned to the idea that The Lady Eve is the twin sister of Jean Harrington, Charles is quickly duped into marriage. However, Jean gets her revenge when, on their honeymoon, knowing Charles is the old-fashioned type, he demands a divorce after Eve confesses to a string of past lovers. Jean’s plot to secure herself a hunk of the Pike fortune in a messy divorce has succeeded. But rather than a sense of victory, Jean feels sadness. She does love Charles after all.

Much like Stanwyck, Fonda plays another kind of trope—a preoccupied bookworm whose opinion of women is that they are fickle and illogical. An unlikely contender in such a romantic comedy, Fonda plays an impeccable straight man, a necessary element in the genre. Not an ounce of humor derives from Charles Pike; he takes himself and his romance very seriously, which is perhaps why he could never imagine the circles that are being run around him by Jean (and Eve). Ever the prideful man, he wants to be, or at least have the appearance that he remains in control. When he confronts Jean on the boat about her criminal past, he pretends to have known about it for days, though he just found out himself, if only to shield his broken heart and further bruise Jean. At once self-deceiving and untried, Charles’ predictability is what brings him together with Jean in the finale. He finds Jean on a cruise ship once more after stumbling over her foot, yet again. Jean, of course, allows Charles believe that he found her, although it was Jean who organized their chance meeting. Happily reunited, the couple forgives the other’s bad behavior with a kiss, several of them in fact. Charles, once again manipulated into taking Jean back to her cabin after his faux victory, remains ignorant to her schemes. Jean has given Charles what he always wanted, and what in Sturges’ assessment every man wants: the illusion of control. Oh, if Charles only knew…

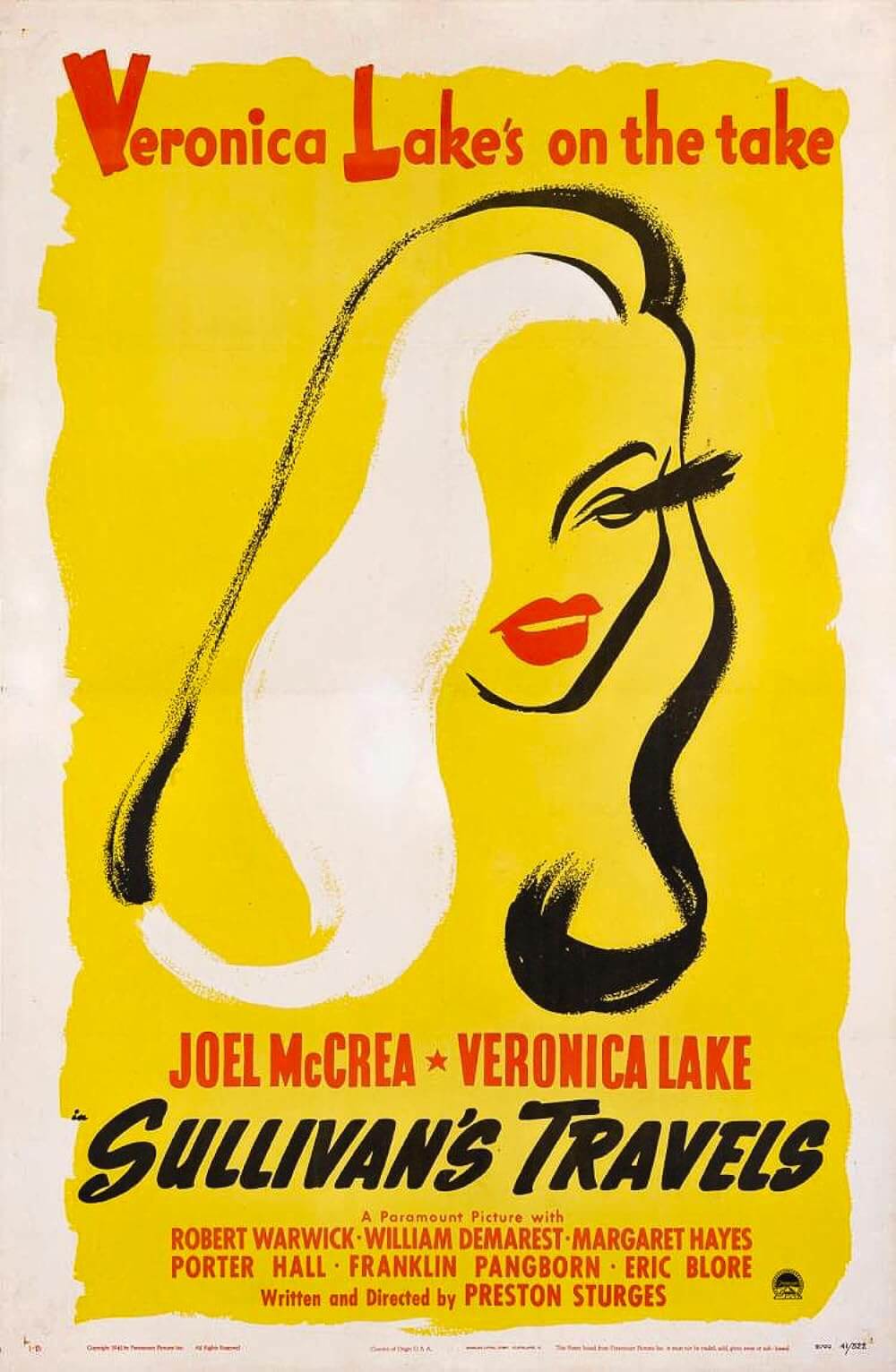

Sturges’ greatest pleasure as a writer and filmmaker was providing moviegoers with a considerable but true laugh—the best quality cinema had to offer, and the most important of all escapes. He once compared a rapt audience with spectators at a tennis match, their heads following the events on the screen as they are directed to in a method Sturges called, “a law of natural interest”. And if Sturges could create such interest through his writing and direction, and further create such a true laugh, not only would the film’s success follow, but he would feel validated as an artist. His project after The Lady Eve, entitled Sullivan’s Travels, embodied this theme in its narrative, being about a serious-minded social filmmaker who comes to realize that comedies help people more than message films. As Sturges’ most singular comedy, The Lady Eve provided audiences with the crucial, easy laugh sought by the writer-director. The film would become his highest grossing film thus far, and one of the highest grossing films of 1941. Its success also made Sturges the highest paid filmmaker in Hollywood and further placed him in the upper echelon of America’s top earners, all by very plainly giving audiences what they want and know, just in a smarter and funnier arrangement than they were accustomed to. When gossip columnist Hedda Hopper asked his about what made his films so successful, he replied, “I have no success formula… I try only to please the public, not the intelligentsia.” To that end, he claimed critical notices did not matter. But elsewhere, Sturges compared a good review to catnip and he the cat. Fortunately, The New York Times’ critic Bosley Crowther, the most powerful critic of the era, compared The Lady Eve to It Happened One Night, Frank Capra’s five-time Oscar-winner and audience favorite.

Sturges’ greatest pleasure as a writer and filmmaker was providing moviegoers with a considerable but true laugh—the best quality cinema had to offer, and the most important of all escapes. He once compared a rapt audience with spectators at a tennis match, their heads following the events on the screen as they are directed to in a method Sturges called, “a law of natural interest”. And if Sturges could create such interest through his writing and direction, and further create such a true laugh, not only would the film’s success follow, but he would feel validated as an artist. His project after The Lady Eve, entitled Sullivan’s Travels, embodied this theme in its narrative, being about a serious-minded social filmmaker who comes to realize that comedies help people more than message films. As Sturges’ most singular comedy, The Lady Eve provided audiences with the crucial, easy laugh sought by the writer-director. The film would become his highest grossing film thus far, and one of the highest grossing films of 1941. Its success also made Sturges the highest paid filmmaker in Hollywood and further placed him in the upper echelon of America’s top earners, all by very plainly giving audiences what they want and know, just in a smarter and funnier arrangement than they were accustomed to. When gossip columnist Hedda Hopper asked his about what made his films so successful, he replied, “I have no success formula… I try only to please the public, not the intelligentsia.” To that end, he claimed critical notices did not matter. But elsewhere, Sturges compared a good review to catnip and he the cat. Fortunately, The New York Times’ critic Bosley Crowther, the most powerful critic of the era, compared The Lady Eve to It Happened One Night, Frank Capra’s five-time Oscar-winner and audience favorite.

Should modern filmmakers take Sturges’ cue, they might sit down with a collection of his films, or those of Lubitsch, Hawks, or Billy Wilder, and learn. Not copy, but rather perceive the devices used and draw from there. Too often audiences see identical scenes from one film to another. Notice how a moment in the schmaltzy Leap Year mirrors one in the better French Kiss, and how they both take from a true original such as I Know Where I’m Gong, and so on. This is because the writers of these modern pictures only know reproduction, and perhaps never learned how to be truly inspired. For them, drawing from the greats requires carbon paper instead of artistic vision. Imagine a Hollywood where young filmmakers sit down to a screening of The Lady Eve and instead of duplicating a tale of a headstrong female card shark falling for a gullible bookworm, they turn out something completely different and equally distinct. But the state of today’s romantic comedies does not require that these films have originality or definition from one another; they exist as part of a factory where the proven formulas are regurgitated because they are easy, proven, and everything else is a risk. Following Sturges, Lubitsch, Hawks, and Wilder, great romantic comedians come few and far between, occasionally falling somewhat inelegantly on names like Woody Allen and Wes Anderson, who are themselves originals, idiosyncratic, and not pure romantic comedians per se, but suffice in today’s market over copycat and remake hounds like Nora Ephron.

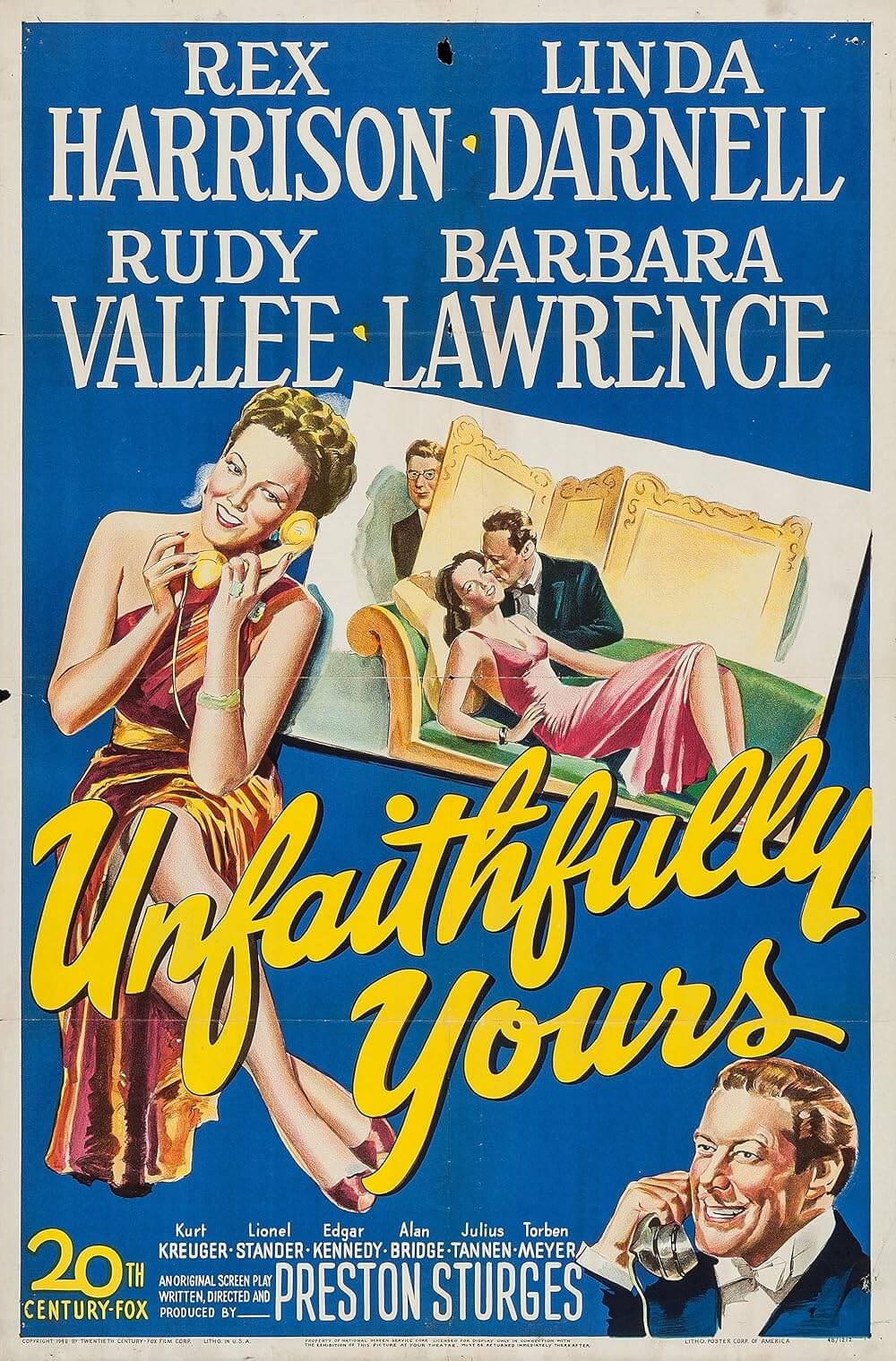

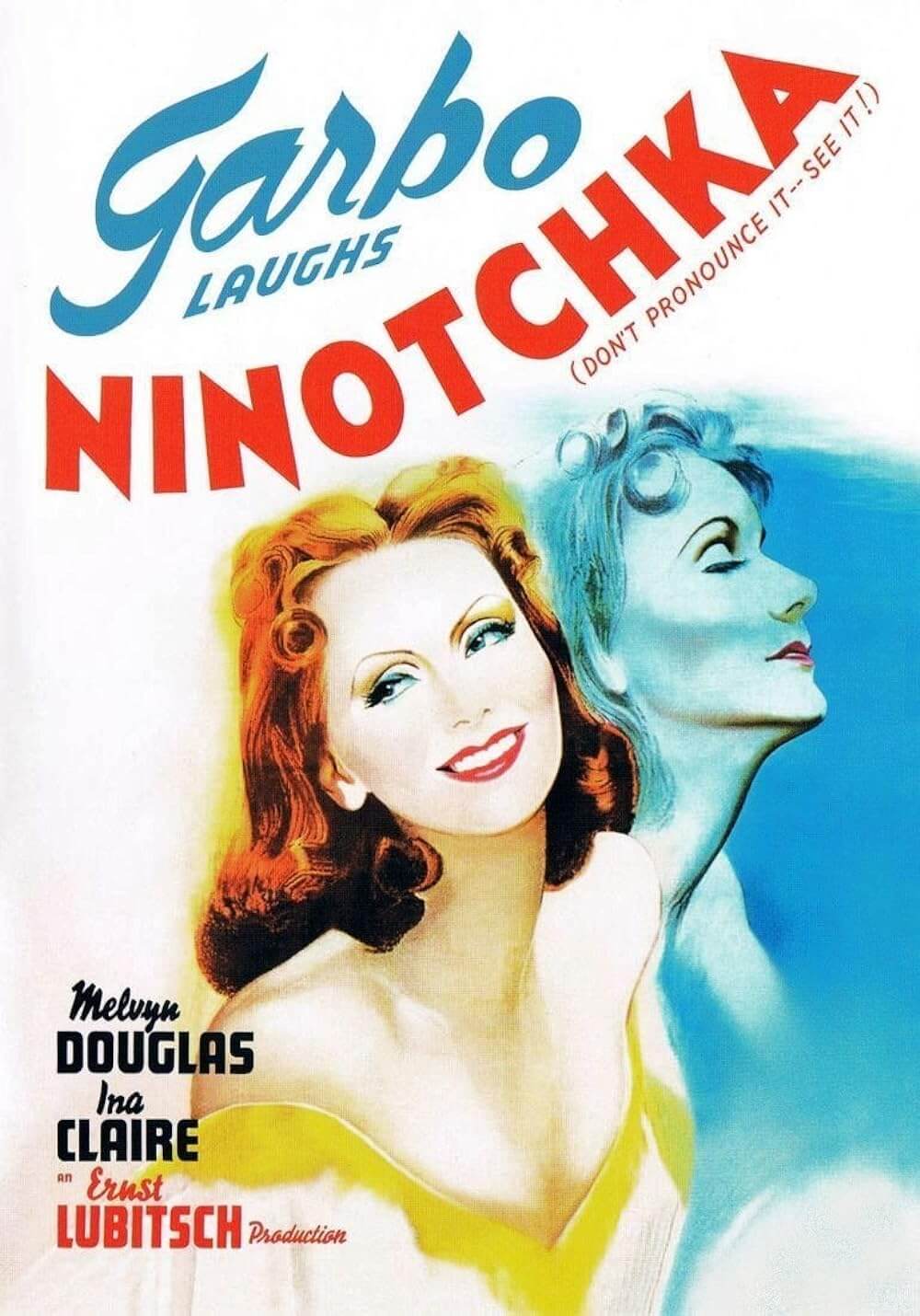

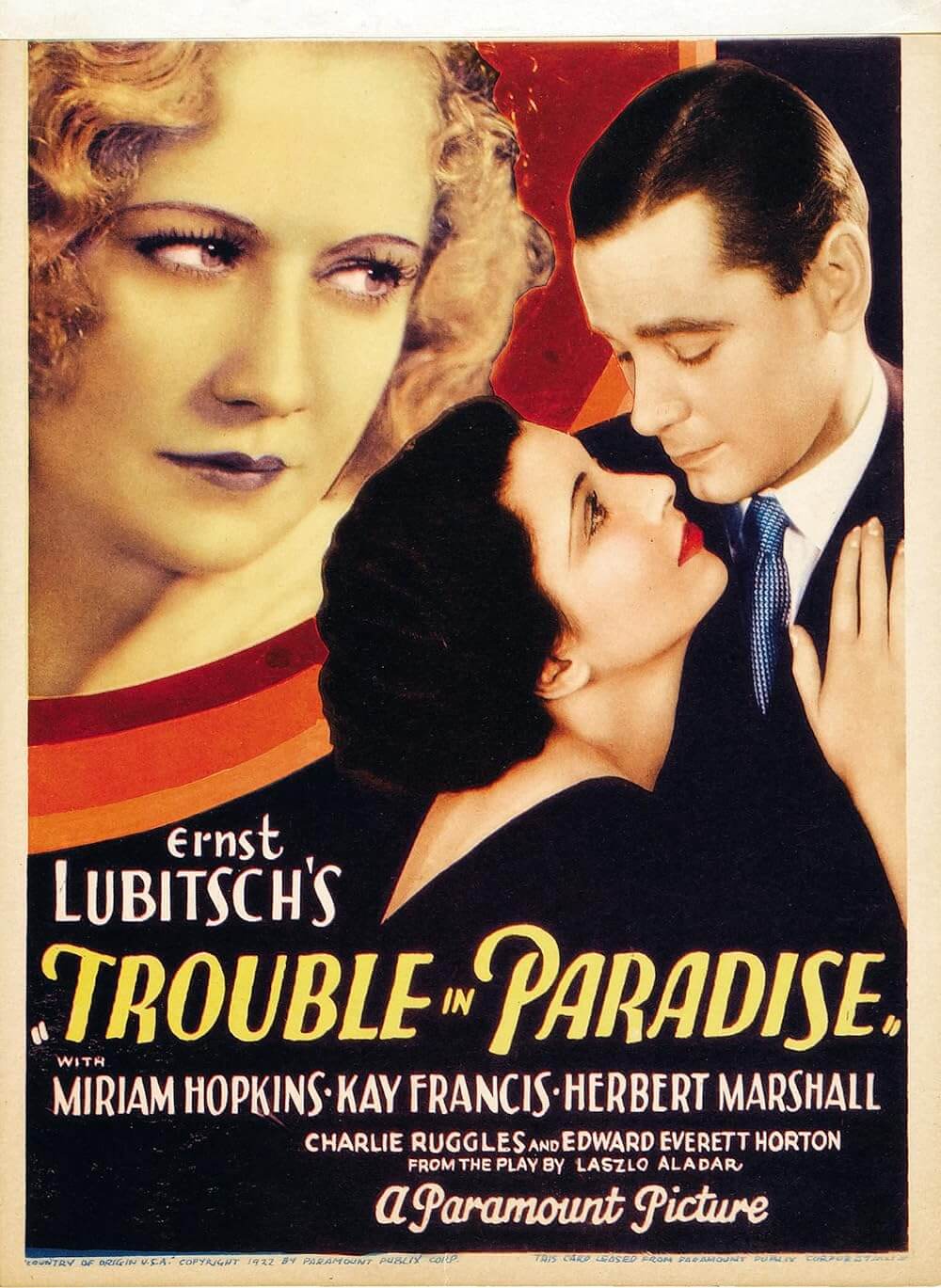

Only a handful of true originals have broadened the romantic comedy genre beyond its conventions. The majority of them draw from the inventor of the romantic comedy as audiences know it, Ernst Lubitsch. With pictures such as Trouble in Paradise and Ninotchka, Lubitsch became renowned for “The Lubitsch Touch,” that fantastical and elusive charisma that is impossible to define but remains undeniably present within all of his films. Balancing romance and drama with silly humor, Lubitsch created a wellspring of material from the early 1920s into the late 1940s. From that source, Hollywood adopted all manner of formulas that are still used today. Sturges admitted his adoration of Lubitsch, but he avoided making retreads of his idol’s films. Though hints of Lubitsch are present in Sturges’ work (Pallette plays an absurd, spoiled father role like the one in Lubitsch’s The Oyster Princess from 1919), he applied his very own sophistication to the formulas so popular in Hollywood at the time. As a rare comedic auteur following the likes of Lubitsch, Sturges curiously avoided butting heads with studio executives over the messages in his films because, in most cases, there were none. Particularly with The Lady Eve, his scripts avoided heavy commentaries or social observations, and rather relied on the richness of his prose to tell the story. He happily toiled for studios like Fox and Paramount, earning millions in box-office receipts because he catered to his audience, but not in such a way that his pictures were intellectual duds. He worked inside the formulas of his predecessors because the studios demanded it, and yet his films avoided becoming merely studio programmers through the undeniable wit of his scenarios.

Only a handful of true originals have broadened the romantic comedy genre beyond its conventions. The majority of them draw from the inventor of the romantic comedy as audiences know it, Ernst Lubitsch. With pictures such as Trouble in Paradise and Ninotchka, Lubitsch became renowned for “The Lubitsch Touch,” that fantastical and elusive charisma that is impossible to define but remains undeniably present within all of his films. Balancing romance and drama with silly humor, Lubitsch created a wellspring of material from the early 1920s into the late 1940s. From that source, Hollywood adopted all manner of formulas that are still used today. Sturges admitted his adoration of Lubitsch, but he avoided making retreads of his idol’s films. Though hints of Lubitsch are present in Sturges’ work (Pallette plays an absurd, spoiled father role like the one in Lubitsch’s The Oyster Princess from 1919), he applied his very own sophistication to the formulas so popular in Hollywood at the time. As a rare comedic auteur following the likes of Lubitsch, Sturges curiously avoided butting heads with studio executives over the messages in his films because, in most cases, there were none. Particularly with The Lady Eve, his scripts avoided heavy commentaries or social observations, and rather relied on the richness of his prose to tell the story. He happily toiled for studios like Fox and Paramount, earning millions in box-office receipts because he catered to his audience, but not in such a way that his pictures were intellectual duds. He worked inside the formulas of his predecessors because the studios demanded it, and yet his films avoided becoming merely studio programmers through the undeniable wit of his scenarios.

Sturges is something of a con artist himself. By hoodwinking the audience into believing The Lady Eve is standard romantic comedy fare, he disguises the genius of the story and the complexity of his characters. The relationship between Jean and her father, for example, has a touching layer of unspoken understanding between the two. While Harry wants to go on relieving suckers of their pocketbooks, he is also Jean’s father and wishes her to be happy. Harry demonstrates how to “deal fives”—where the four aces lay on the top of the deck and the dealer only pulls cards from the fifth spot down, reserving the aces for wherever the dealer chooses—as he questions Jean about her time with Charles the previous evening. Sturges aligns himself with Harry, as both men play with an ace up their sleeve, pretending to be average talents though their ability far exceeds anyone sitting at the table. Likewise, even though formulas are plentiful within the plot of The Lady Eve, Sturges ornaments them through his bright interplay of fast dialogue and clever humor, supplemented by just the right application of slapstick. Take the numerous pratfalls by Fonda’s character—he flops over the couch, slips in the mud, or ends up with a tray of food on his head. These moments are silly, and yet Sturges makes their silliness unwaveringly funny. The writing and timing make the viewer believe in the characters and their actions, however ridiculous, because they acknowledge the truth of the situation while simultaneously laughing at it. Sturges realized the reality of formulas and the importance of exploiting them for the audience’s sake. In doing so, he gives his formula characters the illusion of three-dimensionality, and he enlivened his scenario through the incalculable delight that occurs when an audience recognizes a truth in comedic form.

How badly the romantic comedy needs another Sturges. He was a true original even while relying on Hollywood tropes. Given the discussion of formulas thus far, both this picture and its filmmaker demand that old adage, They don’t make ‘em like they used to. For his part, Preston Sturges anticipated his audience’s needs and sought to enliven their experience with his brand of intelligent comedy. From his understanding of film, Sturges formulated a sophistication to the romantic comedy that has rarely been matched throughout the history of all of cinema. In the case of The Lady Eve, he accomplished this with unparalleled and definite precision, and it remains his most effortlessly funny and charming motion picture. It poses no great questions and contains no lessons about love. It simply provides a romantic and amusing story that awakens the audience, engaging them through its scenario in ways that seem familiar and yet wholly new. Indeed, those who watch the film for the first time may have seen its many varied and subsequent copycats, but they are not likely to find its equal. Sturges’ genius could never be copied with even the most muted sense of success; however, with a bit of luck, his film might inspire another original to emerge and save the dying romantic comedy genre.

How badly the romantic comedy needs another Sturges. He was a true original even while relying on Hollywood tropes. Given the discussion of formulas thus far, both this picture and its filmmaker demand that old adage, They don’t make ‘em like they used to. For his part, Preston Sturges anticipated his audience’s needs and sought to enliven their experience with his brand of intelligent comedy. From his understanding of film, Sturges formulated a sophistication to the romantic comedy that has rarely been matched throughout the history of all of cinema. In the case of The Lady Eve, he accomplished this with unparalleled and definite precision, and it remains his most effortlessly funny and charming motion picture. It poses no great questions and contains no lessons about love. It simply provides a romantic and amusing story that awakens the audience, engaging them through its scenario in ways that seem familiar and yet wholly new. Indeed, those who watch the film for the first time may have seen its many varied and subsequent copycats, but they are not likely to find its equal. Sturges’ genius could never be copied with even the most muted sense of success; however, with a bit of luck, his film might inspire another original to emerge and save the dying romantic comedy genre.

Bibliography:

Curtis, James. Between Flops: A Biography of Preston Sturges. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, c1982.

Harvey, James. Romantic Comedy in Hollywood, from Lubitsch to Sturges. New York: Knopf, 1987.

Sturges, Preston; Sturges, Tom. Preston Sturges by Preston Sturges: His Life in His Words. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1990.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review