The Definitives

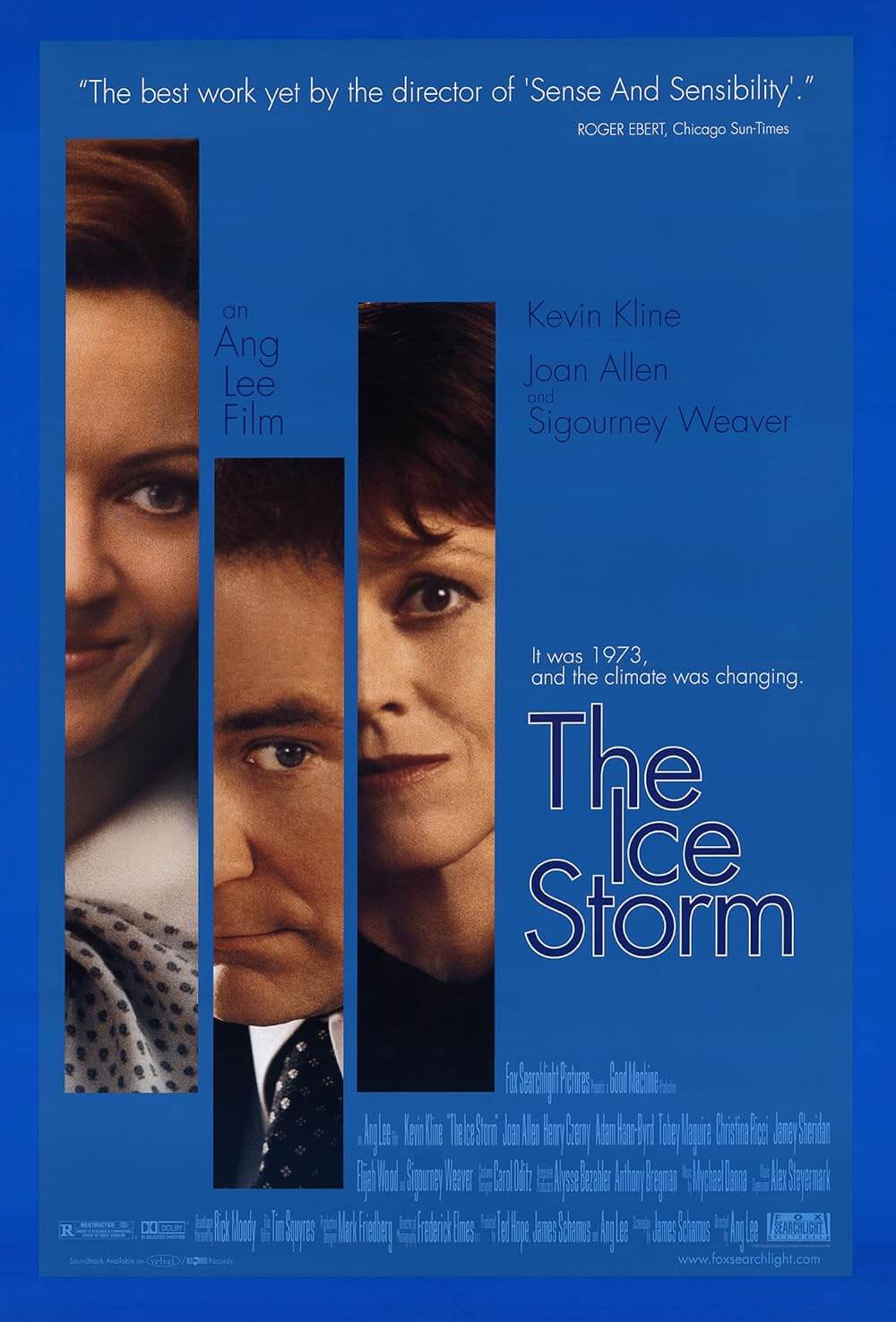

The Ice Storm (1997)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Ang Lee’s The Ice Storm, released by Fox Searchlight in 1997, contains arresting, complex images: a figure moving behind an ice-encrusted window, two adolescents sharing a kiss in a drained swimming pool coated with dead leaves, an ominous clear bowl filled with car keys. Lee’s carefully aestheticized approach establishes a detailed, if bleak and gray world for its disaffected characters, who remain existentially adrift in their 1970s Connecticut suburb. However, the film’s primary artistic method resides in its use of silence and how few of its characters communicate with one another in a clear, meaningful way. Lee’s films often involve characters trying—and failing—to communicate within a precise era and distinct culture; and given his characters’ unconventional specificity and sustained inability to effectively communicate, they offer an alternative to commercially popular types. Such characteristics, along with their method of production and distribution, place many of his films outside of conventional Hollywood modes of filmmaking and into the realm of the indie. This exploration of Ang Lee and The Ice Storm proceeds in part to investigate Lee’s emergence as a filmmaker and arrival on the indie film scene in the 1990s; in part to tell the story of the film, its making, and distribution; and in part to investigate Lee’s auteurist drives. From this survey, many of the director’s lasting themes, but above all those present in The Ice Storm, will be shown to have inherent indie characteristics.

Before engaging in an analysis of The Ice Storm and how it fits into the definition of indie cinema, the indie itself demands clarification. Michael Z. Newman, author of Indie: An American Film Culture, places the indie’s emergence in the mid-1980s and charts its life until the 2000s, calling it a “Sundance-Miramax era” of pointedly American independent filmmaking. The definition itself remains fluid and dependent on several factors of narrative, character, viewership, and distribution. For example, Newman states that an audience must be able to interpret an indie, which inherently contains some degree of narrative and formal ambiguity, including unclear goals for its characters and a presentation that must be read. Indies also contain characters who exist as constructs, demonstrating particular social and political remarks or observations by the filmmaker. Deciphering these qualities requires a level of engagement and work on the viewer’s part that goes against the effortless style of Hollywood, and therefore opposes Hollywood and mainstream sensibilities. Beyond the film itself, the indie’s distribution occurs within a distinct cultural target that often begins on the festival circuit, advances to smaller arthouse or independent theaters, and on rare occasions even advances to larger venues. In most cases, the above factors cannot be measured objectively; they depend on an interpretable, subjective sense of indie authenticity assessed by the viewer, critic, or scholar. Determining whether The Ice Storm is an authentic indie, then, becomes a question of its making and distribution, but above all, how well Lee maintains a cinematic discourse that resists Hollywood standards through the film’s use of character, narrative, and form, and in that challenges his audience to interpret the film.

A Taiwanese-born director working predominantly in the English language, Lee’s recurring theme in his films indicates the fragmentary nature of identity and how, in the search for meaning and individuality, the search itself becomes representative of an overarching, unresolved human struggle. In Lee’s films, identity comes into question through globalization in his various East-meets-West efforts like The Wedding Banquet (1992) or Eat Drink Man Woman (1994), divided senses of patriotism in Ride with the Devil (1999) and Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk (2016), conflicted sexual yearnings in Brokeback Mountain (2005) and Lust, Caution (2007), or clashing religious beliefs in Life of Pi (2012). His films are concerned with cultural expectations that have a bearing on duty, family, and love, as well as the dialectic between modernity and the traditions of the past, often in the face of globalization. By their very nature, many Lee films contain the narrative requirements of an indie since they contain specific characters who feel lost and, though searching for their identity amid otherwise defined choices and worlds, they fail to find it. The common failure of Lee’s characters to resolve their existential crises in a complete, substantial way places his work outside of routine Hollywood tropes—even though, as we will discover later, Lee has often tried, albeit unsuccessfully, to administer his approach onto mainstream efforts.

A Taiwanese-born director working predominantly in the English language, Lee’s recurring theme in his films indicates the fragmentary nature of identity and how, in the search for meaning and individuality, the search itself becomes representative of an overarching, unresolved human struggle. In Lee’s films, identity comes into question through globalization in his various East-meets-West efforts like The Wedding Banquet (1992) or Eat Drink Man Woman (1994), divided senses of patriotism in Ride with the Devil (1999) and Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk (2016), conflicted sexual yearnings in Brokeback Mountain (2005) and Lust, Caution (2007), or clashing religious beliefs in Life of Pi (2012). His films are concerned with cultural expectations that have a bearing on duty, family, and love, as well as the dialectic between modernity and the traditions of the past, often in the face of globalization. By their very nature, many Lee films contain the narrative requirements of an indie since they contain specific characters who feel lost and, though searching for their identity amid otherwise defined choices and worlds, they fail to find it. The common failure of Lee’s characters to resolve their existential crises in a complete, substantial way places his work outside of routine Hollywood tropes—even though, as we will discover later, Lee has often tried, albeit unsuccessfully, to administer his approach onto mainstream efforts.

Lee did not direct his first film until he was 37 years old, but his early years inform his later filmmaking. Born in 1954 in Pingtung County, Taiwan, Lee had the constraints and expectations of Chinese culture bearing down on him to become a successful man. His father, Lee Sheng, a well-educated high school principal, was disappointed by his son’s twice-failed Taiwanese national university entrance exams. Lee would later remark that, during school, he was only good at sneaking away to see movies at the Chin Men Theatre. In 1973, Lee enrolled in the Theater and Film program at the Taiwan Academy of Arts, which brought additional disappointment to his father, as film studies were not considered a respectable field. Lee took to acting, and his stage performances unleashed a repressed inner self that he had not known before: “My spirit was liberated for the first time,” he told an interviewer. Lee’s continued education was delayed by two years due to the military service required by the Taiwanese government; afterward, with the financial support of his family, he arrived in America in 1978 to study theater and directing at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. At the same time, his short black-and-white silent film called Laziness on a Saturday Afternoon (Xingqiliu Xiawu de Lansan, 1976), which he made at the Taiwan Academy of Arts, helped secure his entrance into New York University’s film program.

Lee received his Master of Fine Arts in Film Production from NYU, studying alongside other up-and-coming directors like Spike Lee, while also exploring what would become the recurrent East-meets-West dialectic in his films. His master’s thesis project, the 43-minute A Fine Line (1985), received acclaim but nonetheless began a period creative repression; he failed to generate interest in his scripts and remained out of work for six years. During that time, Lee married Jane Lin, a Ph.D. student he met at the University of Illinois, and she worked as a microbiology researcher while he remained at home with their two children. Only after Lee entered a screenplay contest held by the Taiwanese government was he able make his debut film, Pushing Hands (1991), for which he won several Taiwanese film awards. The film, about a tai chi master who must acclimate to American living, is representative of his early films and their stories about the clashing of Chinese and American cultures. Lee followed Pushing Hands with The Wedding Banquet (1993), a film about a Taiwanese-American gay man who agrees to marry a Chinese woman to secure her a U.S. green card. Both films were co-financed and produced by Good Machine, a small production company founded by Ted Hope and James Schamus.

Lee received his Master of Fine Arts in Film Production from NYU, studying alongside other up-and-coming directors like Spike Lee, while also exploring what would become the recurrent East-meets-West dialectic in his films. His master’s thesis project, the 43-minute A Fine Line (1985), received acclaim but nonetheless began a period creative repression; he failed to generate interest in his scripts and remained out of work for six years. During that time, Lee married Jane Lin, a Ph.D. student he met at the University of Illinois, and she worked as a microbiology researcher while he remained at home with their two children. Only after Lee entered a screenplay contest held by the Taiwanese government was he able make his debut film, Pushing Hands (1991), for which he won several Taiwanese film awards. The film, about a tai chi master who must acclimate to American living, is representative of his early films and their stories about the clashing of Chinese and American cultures. Lee followed Pushing Hands with The Wedding Banquet (1993), a film about a Taiwanese-American gay man who agrees to marry a Chinese woman to secure her a U.S. green card. Both films were co-financed and produced by Good Machine, a small production company founded by Ted Hope and James Schamus.

Hope and Schamus established Good Machine in the early 1990s on characteristically indie ideals. As Hope wrote in his memoir, Hope for Film, the partners sought to make films outside of the norm, yet with “practicalities” in mind that would allow their company to make more than just a single film. They wanted small films to reach their intended audiences—people that Hollywood films had a difficult time reaching: “All those different groups hungry for substantive cinema and unsatisfied with mainstream movies.” Good Machine found investors, secured the film’s place on the festival circuit, ensured distribution through larger companies like Fox Searchlight and Miramax, and in some cases developed marketing strategies for the release of their projects. Hope recounted how one day in 1990, when Good Machine’s small office was above a strip club called New York Dolls in Tribeca, a desperate man with two scripts in a plastic bag came into his office and said, “I’m Ang Lee and if I don’t make a film soon, I’m going to die.” Good Machine went on to produce, and Schamus co-write, eleven of Lee’s thirteen films through 2016. Moreover, the company would produce some of the major indie titles of the 1990s and early 2000s, including Todd Haynes’ Safe (1995), Nicole Holofcener’s Walking and Talking (1996), Todd Solondz’s Happiness (1998), Todd Field’s In the Bedroom (2001), and American Splendor (2003) by the directing team of Shari Springer Berman and Robert Pulcini.

Lee’s reputation in the film industry improved with each new film. His international acclaim and the profitable box-office for The Wedding Banquet helped garner his first Academy Award nomination for Best Foreign Language Film. He received another nomination for his next project, Eat Drink Man Woman (1994), his first film made in Taiwan, about three daughters of a Chinese master chef who favor Western values over those of their deeply Confucian family. Lee’s first three successes brought him the attention producer Lindsay Doran, and he was hired to direct Sense and Sensibility (1995), which he made into the lush production of Jane Austen’s novel. Adapted by Emma Thompson in an Oscar-winning screenplay, the British costume drama contained many similar themes to Lee’s earlier work, namely young people trying to distinguish themselves from their parents, find love, and find themselves within a repressive culture. With Sense and Sensibility, Lee had moved from the “marginalized category of foreign-language film director” to a burgeoning artist talked about throughout Hollywood. His next picture would be The Ice Storm, based on Rick Moody’s 1994 novel, and it would also mark Lee’s first film about entirely American characters in an American setting.

Lee’s reputation in the film industry improved with each new film. His international acclaim and the profitable box-office for The Wedding Banquet helped garner his first Academy Award nomination for Best Foreign Language Film. He received another nomination for his next project, Eat Drink Man Woman (1994), his first film made in Taiwan, about three daughters of a Chinese master chef who favor Western values over those of their deeply Confucian family. Lee’s first three successes brought him the attention producer Lindsay Doran, and he was hired to direct Sense and Sensibility (1995), which he made into the lush production of Jane Austen’s novel. Adapted by Emma Thompson in an Oscar-winning screenplay, the British costume drama contained many similar themes to Lee’s earlier work, namely young people trying to distinguish themselves from their parents, find love, and find themselves within a repressive culture. With Sense and Sensibility, Lee had moved from the “marginalized category of foreign-language film director” to a burgeoning artist talked about throughout Hollywood. His next picture would be The Ice Storm, based on Rick Moody’s 1994 novel, and it would also mark Lee’s first film about entirely American characters in an American setting.

The Ice Storm’s 1970s setting of New Canaan, a Connecticut suburb, may seem like an oddly specific version of America, but it gives way to universal sentiments, such as feelings of isolation and detachment—in terms of family, friends, sexuality, and self-awareness. The winter scenery is bitter, populated by New Age houses amid skeletal trees, dead leaves, and breaths of frigid air—an alienating world to be sure. Kevin Kline and Joan Allen play Ben and Elena Hood, a married couple preparing for Thanksgiving weekend. The Hoods interact with their neighbors, the Carvers, Janey (Sigourney Weaver) and Jim (Jamey Sheridan). All of them have been in couple’s therapy, though Ben and Elena have given up. Ben has been sleeping with Janey, who refuses to grant any emotional significance to their affair. “You’re boring me. I already have a husband,” Janey tells Ben, when he engages in post-coital golf talk. Meanwhile, Elena suspects Ben, but the erasure of her identity in their cold marriage has left her to seek a sense of freedom in the form of long bike rides and shoplifting. The sexual confusion subsists until a dangerous ice storm one night, when an awkward neighborhood “key party” brings the adults together. And after several three-finger pours of vodka, Ben brings his marriage to the brink when he appears visibly upset that he’s not going home with Janey.

While the adults remain preoccupied with their own failing marriages, their children are left alone to experiment and explore. Wendy Hood (Christina Ricci) is the object of affection for the Carver boys, Mikey and Sandy (Elijah Wood, Adam Hann-Byrd), and she tries to figure out her newfound sexual impulses through them. Wide-eyed and spacey, Mikey, who is Wendy’s age, seems to exist on another planet. Sandy Carver, a year or so younger, has a boyish obsession with guns, blowing things up, and general destruction; and yet, Wendy seems drawn to him, in spite of his crippling fear of sexuality—an “I’ll show you mine if you show me yours” moment ends in disaster. Paul Hood (Tobey Maguire), sixteen and away at a private school in Manhattan, pines after a popular girl, Libbets (Katie Holmes), but competes for her affections with a much more sexually experienced boy (David Krumholtz). Both Paul and his sister can see their parents’ marriage falling apart.

While the adults remain preoccupied with their own failing marriages, their children are left alone to experiment and explore. Wendy Hood (Christina Ricci) is the object of affection for the Carver boys, Mikey and Sandy (Elijah Wood, Adam Hann-Byrd), and she tries to figure out her newfound sexual impulses through them. Wide-eyed and spacey, Mikey, who is Wendy’s age, seems to exist on another planet. Sandy Carver, a year or so younger, has a boyish obsession with guns, blowing things up, and general destruction; and yet, Wendy seems drawn to him, in spite of his crippling fear of sexuality—an “I’ll show you mine if you show me yours” moment ends in disaster. Paul Hood (Tobey Maguire), sixteen and away at a private school in Manhattan, pines after a popular girl, Libbets (Katie Holmes), but competes for her affections with a much more sexually experienced boy (David Krumholtz). Both Paul and his sister can see their parents’ marriage falling apart.

The Ice Storm was shot under indie conditions with Lee’s formal choices and attention to detail guiding the production. Schamus adapted Moody’s book and, with a small budget, the production filmed on location in New Canaan, Connecticut, using actual locations such as the town’s train station and main street. Production designer Mark Friedberg and costumer Carol Oditz employed 1970s colors, styles, and fabrics, while cinematographer Frederick Elmes (an indie figure with several collaborations alongside David Lynch and Jim Jarmusch) shot in muted, weathered tones to capture the stifled personality of the film and its characters. Lee instructed Elmes to use intentionally “garish” color, according to Schamus, insisting on a grayed-out palette to reflect its confused, repressed, and disenchanted characters. Lee also worked closely with composer Mychael Danna on the score, which consists of Gamelan instruments (normally used in Indonesian rituals) and Native American flutes. The original score is interrupted by occasional pop songs on the radio from Frank Zappa, Harry Nilsson, and the high school orchestra’s brief cover of Maureen McGovern’s “The Morning After.” However, instead of a more conventional Hollywood production with a soundtrack of start-to-finish ‘70s hits, Danna’s predominant flutes suggest something more significant, even mystical happening onscreen; they avoid telegraphing the intended emotional response the viewer should have to each scene.

The Ice Storm’s detailed mise-en-scène establishes a 1970s setting that might put the audience at a distance if not for the film’s resonant lessons. Lee establishes a 1970s American culture with Bobby Bloom’s 1970 hit “Montego Bay” on the record player, talk of Deep Throat (Gerard Damiano, 1972) in the movie theater, polyester fabrics, leisure suits with long lapels, shag carpets, and waterbeds. In a deeply self-indulgent decade (the so-called “Me” decade), alcohol and sex become escapes characteristic of 1970s social life, used by adults bludgeoned by the Nixon regime, the 1973 gas crisis, the lingering Vietnam conflict, and economic recession. Every adult in the film embraces numbing agents and coping mechanisms, usually appearing with a drink or cigarette in their hands. Most of the principal adult characters also cope through sex with multiple partners—a condition that reaches its peak at the adult “key party,” where everyone in attendance drops their car keys in a bowl and goes home with whoever picks theirs out. Not even the town’s young reverend (Michael Cumpsty) is immune to breaking sexual taboos: “Sometimes the shepherd needs the company of the sheep,” he tells Elena. “I’m going to try hard not to understand the implications of that,” Elena replies. Lee later joked that 1973 was America’s most “embarrassing” year, but that people “two decades later, have much to learn from the ‘embarrassing’ past.”

The Ice Storm’s detailed mise-en-scène establishes a 1970s setting that might put the audience at a distance if not for the film’s resonant lessons. Lee establishes a 1970s American culture with Bobby Bloom’s 1970 hit “Montego Bay” on the record player, talk of Deep Throat (Gerard Damiano, 1972) in the movie theater, polyester fabrics, leisure suits with long lapels, shag carpets, and waterbeds. In a deeply self-indulgent decade (the so-called “Me” decade), alcohol and sex become escapes characteristic of 1970s social life, used by adults bludgeoned by the Nixon regime, the 1973 gas crisis, the lingering Vietnam conflict, and economic recession. Every adult in the film embraces numbing agents and coping mechanisms, usually appearing with a drink or cigarette in their hands. Most of the principal adult characters also cope through sex with multiple partners—a condition that reaches its peak at the adult “key party,” where everyone in attendance drops their car keys in a bowl and goes home with whoever picks theirs out. Not even the town’s young reverend (Michael Cumpsty) is immune to breaking sexual taboos: “Sometimes the shepherd needs the company of the sheep,” he tells Elena. “I’m going to try hard not to understand the implications of that,” Elena replies. Lee later joked that 1973 was America’s most “embarrassing” year, but that people “two decades later, have much to learn from the ‘embarrassing’ past.”

The presence of Richard Nixon on television—defending his imminent impeachment with his “I am not a crook” speech from November 17, 1973—appears throughout the film and suggests a thematic parallel to Ben Hood. Nixon was a postwar father figure, a can-do conformist in a gray flannel suit who played the game (even if he broke the rules), achieved what his culture told him was right, and yet his desperation to preserve his status left his presidency in ruins. The Nixon administration’s Watergate scandal meant the President would resign in August of 1974, reflecting the nation’s breakdown in both the political and private realms. Ben could stand in for Nixon. Ben has everything he is supposed to have according to postwar American ideals—a beautiful wife, two children, a dreamy house in the Connecticut suburbs, and a cushy Wall Street job that he, and dozens of other men in their identical tan raincoats, commute to on the New Canaan train. But his life is unraveling before him, just like Nixon’s, and he remains riddled with discontentment, boredom, and guilt over the ways he tries to cope: namely, alcohol and adultery. And take it as a casting coincidence that Joan Allen played Pat Nixon in Oliver Stone’s 1995 biopic, Nixon, as observed by Robert Sklar in Cinéaste; like her First Lady character, Allen plays Ben’s wife Elena as if “preserving her dignity amid constant humiliation, while occasionally breaking out with startling, pathetic bursts of feeling or will.”

Within its disillusioned 1973 environment, the film contains an almost complete lack of lucid dialogue between characters—who communicate without saying anything meaningful, without listening to one another, and without saying what they really mean. The stifling, passive-aggressive ways in which characters fail to express how they feel—by talking to each other with their backs turned, from another room, or without looking at one another—reveals the film’s central theme: communication, or miscommunication. Though Moody’s novel contains Paul’s omniscient narrator to provide the reader with the inner thoughts of its characters, Schamus filled those gaps with dialogue. However, Schamus’ gap-filling approach is less straightforward that one might expect. The film’s characters speak in unfinished sentences and incomplete ideas; conversations are interrupted, sometimes by a person leaving or entering the room; and insincere politeness is broken by regretful, momentary, and then instantly quieted outbursts of true feeling. Consider a moment between Elena and Ben as they prepare their Thanksgiving feast. The couple, having been married for almost two decades, can finish each other’s sentences; but they use that skill to avoid communicating. In a rare moment, before making love for the first time in a long time, they exchange a few words. Ben says, “You know, Elena. I’ve been thinking…” But Elena cuts in, “Ben, maybe no talking right now. If you start talking, you’re going to…” And then she kisses him, implying that Ben’s way of communicating will spoil the irregular moment of passion.

Within its disillusioned 1973 environment, the film contains an almost complete lack of lucid dialogue between characters—who communicate without saying anything meaningful, without listening to one another, and without saying what they really mean. The stifling, passive-aggressive ways in which characters fail to express how they feel—by talking to each other with their backs turned, from another room, or without looking at one another—reveals the film’s central theme: communication, or miscommunication. Though Moody’s novel contains Paul’s omniscient narrator to provide the reader with the inner thoughts of its characters, Schamus filled those gaps with dialogue. However, Schamus’ gap-filling approach is less straightforward that one might expect. The film’s characters speak in unfinished sentences and incomplete ideas; conversations are interrupted, sometimes by a person leaving or entering the room; and insincere politeness is broken by regretful, momentary, and then instantly quieted outbursts of true feeling. Consider a moment between Elena and Ben as they prepare their Thanksgiving feast. The couple, having been married for almost two decades, can finish each other’s sentences; but they use that skill to avoid communicating. In a rare moment, before making love for the first time in a long time, they exchange a few words. Ben says, “You know, Elena. I’ve been thinking…” But Elena cuts in, “Ben, maybe no talking right now. If you start talking, you’re going to…” And then she kisses him, implying that Ben’s way of communicating will spoil the irregular moment of passion.

In other cases, the lack of clear communication is unintentional. When Janey catches Wendy and Sandy exploring each other’s bodies, she clumsily tries to convey a sense of Catholic shame: “A person’s body is his temple, Wendy. This is your first and last possession.” Perhaps realizing her own moral hypocrisy, Janey shifts gears in an equally clumsy social argument: “In Samoa and in other developing nations, adolescents are sent out into the woods, unarmed, and they don’t come back until they’ve learned a thing or two.” With Wendy properly confused, Janey sends the girl home. In a similarly awkward talk about sex between an adult and his child, Ben attempts to broach the subject with Paul, stumbles, and resolves not to continue: “Could you do me a favor and pretend I never said any of that?” Poor communication in the film also extends to one character’s awareness, or lack thereof, of another character’s presence in the room or household. When Jim returns home from a business trip, he greets his children, “Hey, guys. I’m back.” Mikey replies, “You were gone?” In another scene, Paul recommends Dostoyevsky’s book The Idiot to Libbets, but she does not respond the way he would like. “I think you’d really like it,” he says and, after a long pause with no reply, pathetically repeats the title, “…The Idiot.” In each case, the film’s characters remain unable to make stable, meaningful connections with one another through communication, and this condition never resolves itself in a convenient, Hollywood way.

The unexpressed or poorly articulated feelings and thoughts in The Ice Storm create a lasting state of repression among the characters, often represented by Lee’s use of complete silence, to the degree that the search for human connection feels almost futile by the end. To achieve this, Lee explores the barriers between people, or even those which the characters establish themselves, that prevent clear communication. For instance, Wendy puts on a rubber Halloween mask of Richard Nixon rather than face Mikey during their sexual exploration in his basement. “Sex in this film is more like a grotesque form of humanity’s failure to communicate,” wrote Sklar, as the earlier referenced moment between Ben and Elena demonstrates as well. Jake Gyllenhaal, costar of Lee’s Brokeback Mountain, once said Lee is “fluent in the language of silence,” and this is evidenced by the several minutes of virtual silence at the end of The Ice Storm, which play almost free of any dialogue. As the Carver family mourns over an unexpected death, the Hoods come together at the train station, and Lee observes these moments through the expressions on his actors’ faces, their tears, and the way they refuse to speak even in the direst moments. The last shot of the Hoods together in the family car shows Ben weeping audibly in front of his family, and the lack of dialogue is broken by Elena, saying “Ben… Ben…” trying to quiet his display of emotion in front of the children.

The unexpressed or poorly articulated feelings and thoughts in The Ice Storm create a lasting state of repression among the characters, often represented by Lee’s use of complete silence, to the degree that the search for human connection feels almost futile by the end. To achieve this, Lee explores the barriers between people, or even those which the characters establish themselves, that prevent clear communication. For instance, Wendy puts on a rubber Halloween mask of Richard Nixon rather than face Mikey during their sexual exploration in his basement. “Sex in this film is more like a grotesque form of humanity’s failure to communicate,” wrote Sklar, as the earlier referenced moment between Ben and Elena demonstrates as well. Jake Gyllenhaal, costar of Lee’s Brokeback Mountain, once said Lee is “fluent in the language of silence,” and this is evidenced by the several minutes of virtual silence at the end of The Ice Storm, which play almost free of any dialogue. As the Carver family mourns over an unexpected death, the Hoods come together at the train station, and Lee observes these moments through the expressions on his actors’ faces, their tears, and the way they refuse to speak even in the direst moments. The last shot of the Hoods together in the family car shows Ben weeping audibly in front of his family, and the lack of dialogue is broken by Elena, saying “Ben… Ben…” trying to quiet his display of emotion in front of the children.

The film’s titular storm is a metaphor that reflects the characters, their repression, and their inability to communicate, but it also reflects an actual event. Over Thanksgiving in 1973, a notorious storm hit New England; heavy rains turned to ice in the freezing temperatures, leaving everything covered in a slippery, motionless surface. Moody grew up in New Canaan where his novel was set and experienced the 1973 ice storm just a month after turning thirteen. The formative event echoes in his characters. Lee captures their isolation, detachment, and uncertainty by highlighting the results of the storm itself, which had to be recreated artificially for the production. In the film’s bleak and frozen world, everyone moves about surrounded by ice-encased branches, driving with caution on slippery roads. On the night of the storm, the film’s characters are separated and alone, trying to find each other. Mikey wanders off to explore the phenomenon, but he dies when a branch, breaking under the weight of the ice, snaps a telephone line and electrocutes him. Though the events would have resulted in dramatic closure in a lesser film, The Ice Storm ends with a boundless silence.

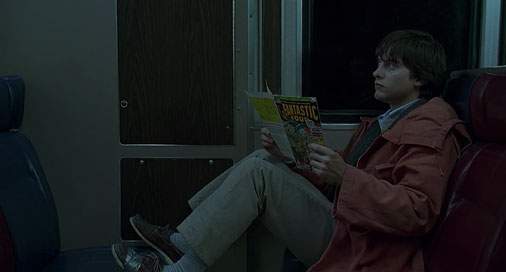

Beyond the ice storm, the film contains another apt metaphor for the central nuclear family. On the train home to New Canaan, Paul reads issue number 141 of Fantastic Four, the Marvel comic about a family of four that is struck by cosmic rays and granted superpowers. In the issue, the villain Annihilus turns the son of hero Reed Richards into a living bomb, requiring the father to use an anti-matter ray to counterbalance the energy now within his son, which in turn leaves his son frozen. Lee’s camera passes by the comic’s panels, which read, “After what you just did, there can’t be a team anymore. This is the end… the end of the Fantastic Four.” The metaphor places Ben in the role of Reed Richards; Elena in place of the invisible woman, Sue Storm; Wendy and her experimental sensibilities in place of the fiery Human Torch; and Paul as The Thing, a physical monster rejected by all but his blind girlfriend. Like Reed Richards’ choice in the comic, Ben’s adultery, propelled by the family’s inability to communicate, leads to the destruction of Paul’s vision of his family. Reading his comic, Paul compares family to anti-matter, suggesting that matter and anti-matter must always return to one another. Similarly, in his narration, Paul extends the metaphor and describes family as death or “our personal negative matter” that thrusts a person “into negative space.” At this moment, Paul realizes his family is not a team, but a dysfunctional whole led by a destructive figurehead. Nevertheless, the laws of Nature compel Paul to return to them.

Beyond the ice storm, the film contains another apt metaphor for the central nuclear family. On the train home to New Canaan, Paul reads issue number 141 of Fantastic Four, the Marvel comic about a family of four that is struck by cosmic rays and granted superpowers. In the issue, the villain Annihilus turns the son of hero Reed Richards into a living bomb, requiring the father to use an anti-matter ray to counterbalance the energy now within his son, which in turn leaves his son frozen. Lee’s camera passes by the comic’s panels, which read, “After what you just did, there can’t be a team anymore. This is the end… the end of the Fantastic Four.” The metaphor places Ben in the role of Reed Richards; Elena in place of the invisible woman, Sue Storm; Wendy and her experimental sensibilities in place of the fiery Human Torch; and Paul as The Thing, a physical monster rejected by all but his blind girlfriend. Like Reed Richards’ choice in the comic, Ben’s adultery, propelled by the family’s inability to communicate, leads to the destruction of Paul’s vision of his family. Reading his comic, Paul compares family to anti-matter, suggesting that matter and anti-matter must always return to one another. Similarly, in his narration, Paul extends the metaphor and describes family as death or “our personal negative matter” that thrusts a person “into negative space.” At this moment, Paul realizes his family is not a team, but a dysfunctional whole led by a destructive figurehead. Nevertheless, the laws of Nature compel Paul to return to them.

Metaphors aside, the film’s social and political backdrop mirrored the culture in which it was released. Newman states that a film’s identification as an indie requires it to reflect an equal measure of “existential angst and alienation” in the context of its contemporary era. When The Ice Storm came out in the fall of 1997, the sexual scandal between the newly re-elected President Bill Clinton and staffer Monica Lewinsky had just broke, talks of Whitewater filled the media, and discussions of impeachment were in the air. The film’s setting of sexual confusion, political discord amid the Nixon regime, and similar discussion of impeachment certainly reflected its present-day conditions. Newman also argues that indie characters can be so representative of certain social realities that they come to emblematize them, and The Ice Storm represents the 1970s milieu of suburban America and its characters afflicted by that era’s collective disenchantment. Lee said of the film, “I think if the movie moves people, it’s because it has a subtext that’s universal, that anyone, from any culture, can relate to.” Whether audiences were willing to allow themselves to be moved, or were interested in connecting to the film’s bleak emotional states, is another question altogether.

In terms of its indie distribution, the film’s release by “mini-major” Fox Searchlight threatens to remove The Ice Storm’s claim to any indie status. The film debuted at the 1997 Cannes Film Festival on May 1, where Schamus won an award for his screenplay. But unlike Fox Searchlight’s other crowd-pleasing films disguised as indies, such as Sideways (Alexander Payne, 2004) and Little Miss Sunshine (Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris, 2006)—whose indieness can be easily dismissed given their happy endings, almost universal acclaim, and connection with mainstream audiences—The Ice Storm remained an outsider. Like many of their indie films, Fox Searchlight began a gradual release of the film in the September following its Cannes debut, placing it on just three screens to major attendance; however, The Ice Storm failed to connect with larger crowds and earned only just over $8 million in its theatrical run. Critics like Roger Ebert praised the film for its “well-observed” approach toward character, while Todd McCarthy in Variety narrowed the film’s limited commercial appeal to “upscale situations.” The Ice Storm’s commercial failure removes the film from a category engineered-for-success titles de-authenticated from their indie status due to their commercial victory, and its indieness remains intact in spite of Fox Searchlight’s overestimation the film’s broad appeal.

In terms of its indie distribution, the film’s release by “mini-major” Fox Searchlight threatens to remove The Ice Storm’s claim to any indie status. The film debuted at the 1997 Cannes Film Festival on May 1, where Schamus won an award for his screenplay. But unlike Fox Searchlight’s other crowd-pleasing films disguised as indies, such as Sideways (Alexander Payne, 2004) and Little Miss Sunshine (Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris, 2006)—whose indieness can be easily dismissed given their happy endings, almost universal acclaim, and connection with mainstream audiences—The Ice Storm remained an outsider. Like many of their indie films, Fox Searchlight began a gradual release of the film in the September following its Cannes debut, placing it on just three screens to major attendance; however, The Ice Storm failed to connect with larger crowds and earned only just over $8 million in its theatrical run. Critics like Roger Ebert praised the film for its “well-observed” approach toward character, while Todd McCarthy in Variety narrowed the film’s limited commercial appeal to “upscale situations.” The Ice Storm’s commercial failure removes the film from a category engineered-for-success titles de-authenticated from their indie status due to their commercial victory, and its indieness remains intact in spite of Fox Searchlight’s overestimation the film’s broad appeal.

After The Ice Storm, Lee continued with films that were often unconventional, but perhaps not indies, and alternated between commercial failures and successes. The underappreciated Ride with the Devil, released by Universal Pictures, once again found Maguire at the center of a historical human drama, this time questioning his loyalty to the South in the midst of the Civil War. In 2000, Lee had his biggest achievement with the Mandarin-language film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, which the independent acquisition division of Sony Pictures Classics distributed stateside. The blockbuster would eventually become the highest-grossing foreign language film ever released in the U.S. at the time, and its popularity earned the film four Oscars, including Best Foreign Language Film. With his newfound celebrity after Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Lee attempted to go Hollywood with his comic book blockbuster Hulk (2003). But after Hulk’s commercial and critical failure, Lee fell into a depression; he contemplated giving up filmmaking altogether before resolving to direct a script for Brokeback Mountain that had come across his desk several times over the years. The indie film represented a much-discussed landmark of queer cinema, earning Lee an Academy Award for Best Director. Afterward, he made the erotic thriller Lust, Caution in 2007, a Mata Hari tale set during the Japanese occupation of China and released by Schamus’ Focus Features. With the mid-sized period comedy Taking Woodstock (2009), Lee made another attempt at mainstream cinema that resulted in a commercial and artistic failure. After he had received his second Oscar for Best Director for his technical and narrative breakthrough Life of Pi, Lee released Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, a production marred by its multi-tiered frame-rate distribution plan (copies of the film at 120-, 48-, and 24-frames-per-second, some of them in 3D, circulated the U.S., confusing audiences).

Throughout his body of work, Ang Lee has resisted conventional modes of filmmaking, leaving his films difficult to contain with genre descriptors or Hollywood sales pitches—The Ice Storm above all. The novelistic film does not translate its characters’ complex behaviors or motivations for its audience, thus maintaining its interpretable quality required for a true indie film. Beyond a dead child, sexual complexes, and a family’s uncertain fate, there are unanswered questions to consider: Why does Mikey behave so strangely? Will Ben and Elena stay together? What will come of these characters? The audience must answer such questions for themselves, as the characters remain incapable of communicating in a way the viewer can understand without interpretation, and the narrative resists providing simple answers. Additionally, The Ice Storm’s unflinching critique of the American Dream and portrayal of its failure show Lee operating as an artist, without concern for the potentially uncommercial prospects of his film’s message. The film’s dark, sexually, socially, and politically confronting subject matter resists the commercial demands of faux indies designed for success, as its commercial failure attests. The Ice Storm contains a deeply human authenticity and willingness to portray, but not resolve, its characters’ collective alienation. That the viewer must interpret and feel the silences between these characters establishes the ambiguous and investigatory mode of watching the film, thus challenging the viewer with prolonged consideration.

Throughout his body of work, Ang Lee has resisted conventional modes of filmmaking, leaving his films difficult to contain with genre descriptors or Hollywood sales pitches—The Ice Storm above all. The novelistic film does not translate its characters’ complex behaviors or motivations for its audience, thus maintaining its interpretable quality required for a true indie film. Beyond a dead child, sexual complexes, and a family’s uncertain fate, there are unanswered questions to consider: Why does Mikey behave so strangely? Will Ben and Elena stay together? What will come of these characters? The audience must answer such questions for themselves, as the characters remain incapable of communicating in a way the viewer can understand without interpretation, and the narrative resists providing simple answers. Additionally, The Ice Storm’s unflinching critique of the American Dream and portrayal of its failure show Lee operating as an artist, without concern for the potentially uncommercial prospects of his film’s message. The film’s dark, sexually, socially, and politically confronting subject matter resists the commercial demands of faux indies designed for success, as its commercial failure attests. The Ice Storm contains a deeply human authenticity and willingness to portray, but not resolve, its characters’ collective alienation. That the viewer must interpret and feel the silences between these characters establishes the ambiguous and investigatory mode of watching the film, thus challenging the viewer with prolonged consideration.

Bibliography:

Dilley, Whitney Crothers. The Cinema of Ang Lee: The Other Side of the Screen. Wallflower Press, 2007.

Hope, Ted and Anthony Kaufman. Hope for Film. Soft Skull Press, 2014.

Moody, Rick. The Ice Storm. Little, Brown & Co., 1994.

Newman, Michael Z. Indie: An American Film Culture. Columbia University Press, 2001.

Schamus, James. The Ice Storm: The Shooting Script. Newmarket Press, 1997.

Silbergeld, Jerome. “Ang Lee’s America, in Living Colour.” Journal of Chinese Cinemas, vol. 6, no. 3, Sept. 2012, pp. 283-297.

Sklar, Robert. “The Ice Storm.” Cinéaste, No. 2, 1997.

Zhang, Jingpei. A Ten-year Dream: The Ang Lee Story. CITIC Press Corporation, 2013.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review