The Definitives

The Hitch-Hiker (1953)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

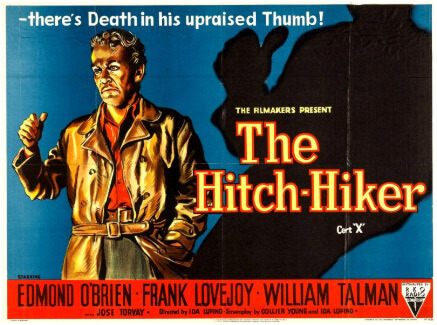

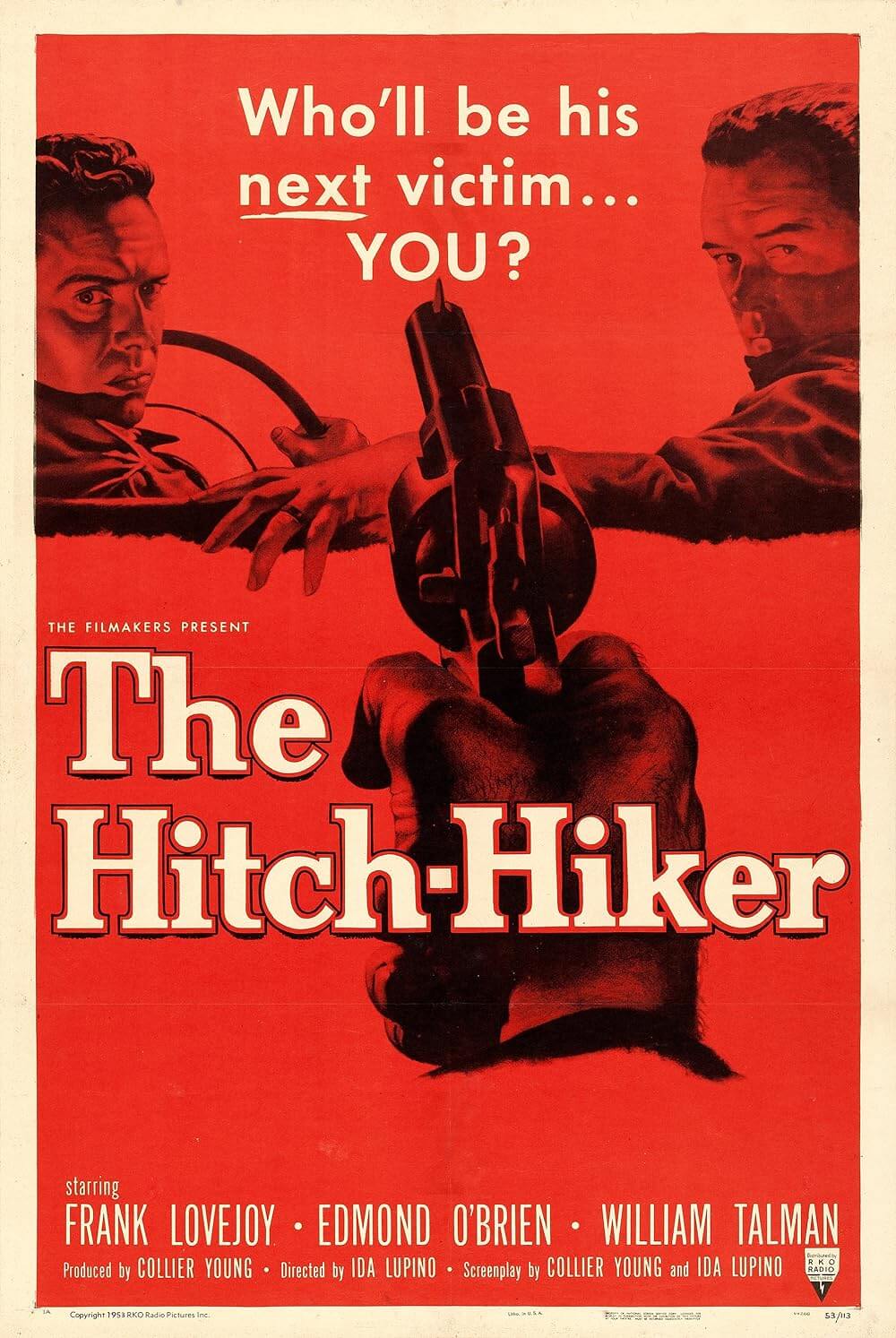

The Hitch-Hiker is a thriller about a psychopathic murderer who kidnaps two men and forces them on a tension-packed ride. Based on an actual crime and made with documentary-style realism, the 1953 film arrived at a time when film noir and social problem pictures fascinated audiences. Its efficient, straightforward storytelling and sharp application of suspense resemble a taut little programmer on the surface. But its co-writer and director, Ida Lupino, uses the scenario to expose the lack of control in postwar America. Lupino, a rare woman director of the era, shot a series of low-budget, independently produced pictures in Hollywood. Her distinct perspective, which neither aligns with the typical studio outlook nor a decidedly feminist one, turns The Hitch-Hiker into a film that characterizes the social oppression of postwar America on the individual. Lupino’s approach defies easy descriptions. Her subsequent critics would dismiss the greatness of her directing career, claiming that she lacks a clear authorial voice or precise feminist viewpoint and that she failed to make one spectacular film. Her defenders recognize her as a rare example of a woman who broke barriers and managed to operate both within and independently of Hollywood. Lupino’s example may not obey the strict definitions of auteurism, but mining her films, The Hitch-Hiker most of all, uncovers her interest in the idyllic American Dream as a crumbling façade, behind which the individual is suppressed.

Born in London to a theatrical family, including an actor mother and comedian father, Ida Lupino (1918-1995) was raised around performers. She received her start in the theater as a teenager before moving into pictures. She appeared in several films for small British studios and eventually made her way to Hollywood. There, she earned a reputation for playing no-nonsense and working-class women, appearing in films like They Drive by Night (1940) and The Sea Wolf (1941) for Warner Bros. directors such as Michael Curtiz, Nicholas Ray, and Rouben Mamoulian. Known for her professionalism and interest in the craft, she worked closely with her directors to develop her characters and maintain control over her on-screen image. But like many actors with a creative spirit, she sought independence. Eventually, she would break away from the studios to form her own company, where she co-wrote and directed six features that each tackled controversial subject matter as only “B” productions could. Though her films dealt with social themes such as rape, disability, illegitimate children, and bigamy, the decades following her work have been filled with questions about whether or not Lupino deserves the status of an auteur and feminist icon. The former designation can be found in her worldview, which is readily apparent throughout her directorial work. The latter proves a challenge under the strict definitions of “feminist” put forth by second- and third-wave thinkers, which often overlook Lupino’s exceptional role as a director when there were practically no other women filmmakers in Hollywood.

Lupino transitioned from an actor into a does-it-all filmmaker during the postwar era. Along with her husband and co-producer Collier Young, Lupino founded her company, initially called Emerald Films, which was later retitled simply The Filmmakers, Inc. With her own company, Lupino would write, direct, and sometimes star in six pictures between 1949 and 1953. An outfit like The Filmmakers supplied a cheap alternative to the usual mode of production for studios who were struggling in a perfect storm of diminishing revenue. For starters, the 1945 union strikes meant increased salaries for filmworkers and fewer profits for the studios. In 1946, the box-office experienced a sharp decline in receipts, causing studios to reevaluate their expenses. Restrictions on Hollywood exports—in the UK and Italy above all, where a movement to build national cinemas was underway—meant the studios would earn less from international audiences. But the most important change entailed the Supreme Court’s decision to pursue an antitrust action against the studios in the famous Paramount Consent Decrees, which prevented studios from the monopolistic practice of owning theatres that would exclusively show only their movies (the decree was ended in 2020). Without studio-owned theaters and the practice of block-booking, which grouped several films from a company under a single exhibition license, thus ensuring the studio profits, the prospect of producing and distributing the same volume of pictures meant a higher financial risk. Given these shifts, the Hollywood studios viewed pictures by independent production companies like The Filmmakers as low-risk ventures they could distribute for an easy profit. This allowed Lupino to flourish for a brief time as one of the only woman filmmakers working in Classical Hollywood.

Lupino transitioned from an actor into a does-it-all filmmaker during the postwar era. Along with her husband and co-producer Collier Young, Lupino founded her company, initially called Emerald Films, which was later retitled simply The Filmmakers, Inc. With her own company, Lupino would write, direct, and sometimes star in six pictures between 1949 and 1953. An outfit like The Filmmakers supplied a cheap alternative to the usual mode of production for studios who were struggling in a perfect storm of diminishing revenue. For starters, the 1945 union strikes meant increased salaries for filmworkers and fewer profits for the studios. In 1946, the box-office experienced a sharp decline in receipts, causing studios to reevaluate their expenses. Restrictions on Hollywood exports—in the UK and Italy above all, where a movement to build national cinemas was underway—meant the studios would earn less from international audiences. But the most important change entailed the Supreme Court’s decision to pursue an antitrust action against the studios in the famous Paramount Consent Decrees, which prevented studios from the monopolistic practice of owning theatres that would exclusively show only their movies (the decree was ended in 2020). Without studio-owned theaters and the practice of block-booking, which grouped several films from a company under a single exhibition license, thus ensuring the studio profits, the prospect of producing and distributing the same volume of pictures meant a higher financial risk. Given these shifts, the Hollywood studios viewed pictures by independent production companies like The Filmmakers as low-risk ventures they could distribute for an easy profit. This allowed Lupino to flourish for a brief time as one of the only woman filmmakers working in Classical Hollywood.

It seems only natural during this period that Lupino’s interests as a filmmaker would confront the postwar uncertainty prevalent in America with a film like The Hitch-Hiker, which adopts elements of film noir, a genre designed to reflect the anxieties and moral ambiguities defining the era. After World War II, film noir raised questions about everything the battle overseas had fought to preserve. Through a cynical lens marked by shadow and fatalism, the American Dream would become suspect, the American family broken, and American capitalism revealed as a corrupting force exploited by criminals. The country had earned its victory with the unthinkable use of nuclear weapons, allowing soldiers to return home, settle into middle-class contentment, and order their wives back into homemaker roles. The mass production of television sets and automobiles, along with rampant advertising, placed goods over goodness, leading to the commodification of one’s identity. Veterans, once heroes with a straightforward purpose, came back to the states and were shuffled into the stifling roles of father, husband, and breadwinner. But inside, men in gray-flannel suits felt uneasy and desired to express themselves outside of conformity. Some never even acquired the suit; they reached right for a gun. In Lupino’s films, reintegration is less the culprit than the hollow, pre-fab world that people were expected to inhabit.

Lupino explored these ideas in her work, having learned the craft from her directors in the 1930s and early 1940s—above all Raoul Walsh, who directed her in four films, including High Sierra (1941) and The Man I Love (1946). But her films are not the usual Hollywood scenarios; as observed in Ronnie Scheib’s auteurist analysis of Lupino’s work in Film Comment, they are about people who have promising lives but find themselves trapped by American society. Whether they are unsure about what they want or have become victims to circumstance, they remain yielding. Some critics have called her characters passive victims to the worlds they occupy. The passivity in her films is uneasy, dangerous, and oppressive so as to be viewed as malignant. In her debut film behind the camera, Not Wanted (1949), for which she took no credit because Elmer Clifton, who was originally hired to direct, died of a heart attack, her protagonist, a mother of an unwanted baby, floats aimlessly from bus stations to a home for unwed mothers to a jail cell. Her second film, Never Fear (1950), follows a skilled dancer who questions the point of life when she contracts polio. Outrage (1950) tells the story of a rape victim who feels disconnected and alienated from the world after her experience, and a series of doctors and various members of the justice system keep her afloat. Women who have their decisions made for them is another frequent theme in Lupino’s film, such as Hard, Fast and Beautiful (1951), where a tennis pro weighs her desire to marry and settle down against her mother’s insistence that she continue playing the sport professionally. But her male characters were also gripped by indecision in the face of expectation, as in The Bigamist (1953), which finds a man maintaining two wives in separate cities out of dire obligation.

In each case, Lupino’s lost characters search the country for meaning but find only a conditional alternative. This preoccupation, a quality of her work with The Filmmakers, affirms her place as the most visible and significant woman director of the otherwise male-dominated Hollywood of the era. She was an author because she co-wrote most of her scripts, but she also fits the mold of an auteur with her thematic preoccupations. To be sure, Lupino draws from her roots in the socially minded productions of Warner Bros., often blending aspects of the “social problem picture” with the “women’s picture,” albeit with a worldview that suggests her displaced characters will go on searching. Her narratives progress in a familiar trajectory by questioning so-called normal society with dispirited characters who live troubled lives. Her characters are often blind to their own search for a stable identity, and they remain unable to help themselves or conform to the American Dream. For Lupino, inaction, followed by a conditional resolution, is the defining characteristic of a postwar America. Desires and happy endings are achieved only through compromises. The Hitch-Hiker takes these issues and winds them into a clever knot, which has been misread by critics, among them Dan Georgakas who called the film “largely devoid of social content,” as a straightforward thriller.

In each case, Lupino’s lost characters search the country for meaning but find only a conditional alternative. This preoccupation, a quality of her work with The Filmmakers, affirms her place as the most visible and significant woman director of the otherwise male-dominated Hollywood of the era. She was an author because she co-wrote most of her scripts, but she also fits the mold of an auteur with her thematic preoccupations. To be sure, Lupino draws from her roots in the socially minded productions of Warner Bros., often blending aspects of the “social problem picture” with the “women’s picture,” albeit with a worldview that suggests her displaced characters will go on searching. Her narratives progress in a familiar trajectory by questioning so-called normal society with dispirited characters who live troubled lives. Her characters are often blind to their own search for a stable identity, and they remain unable to help themselves or conform to the American Dream. For Lupino, inaction, followed by a conditional resolution, is the defining characteristic of a postwar America. Desires and happy endings are achieved only through compromises. The Hitch-Hiker takes these issues and winds them into a clever knot, which has been misread by critics, among them Dan Georgakas who called the film “largely devoid of social content,” as a straightforward thriller.

Lupino considered The Hitch-Hiker to be her best film, and it’s difficult to name its superior in her body of work. The story centers on two average guys, Roy Collins (Edmond O’Brien) and Gilbert Bowen (Frank Lovejoy), who become prisoners of a killer—an ex-con named Emmet Myers (William Talman), dubbed the “Hitch-Hike Slayer” by the newspapers. Like his country, Myers tries to veil his insecurities and cruelty with macho violence. Lupino critiques his brand of masculinity, which feeds on the postwar American Dream by killing it. But she also questions another kind of man, represented by Myers’ captives, who quietly suffers under punishing, existentially stifling conditions. Collins and Bowen, longtime friends from California, take a road trip, their first time alone together in years. The war and marriage have consumed their lives, restricting them with orders, duty, and social responsibility, and the two men have set out for the first time away from their obligations to reclaim their masculinity, if only for a few days. They told their wives they would be hiking around Arizona’s Chocolate Mountains, but instead, they drive to Mexico for a fishing trip, and perhaps something more. Collins seems intent on stopping in Mexicali for a night of drinking and women; Bowen pretends to be asleep to avoid the temptation. But their escape from domesticity leads to another claustrophobic situation when they pick up Myers, a murderer who quickly turns his gun on them and forces them to submit to his will.

Lupino and Young based their screenplay on the mass murders of Billy Cook, which took place between December 30, 1950, and January 21, 1951. A psychopath angry at the world, Cook killed six people and shot another four while pretending to be a hitchhiker. After a thankless childhood as an orphan and teenage years spent in state-ordered reform school, Cook became violent and antisocial. He had the words “Hard Luck” tattooed across his fingers on both hands, and his malformed right eyelid remained creepily open. When petty crimes landed him inside a Missouri penitentiary, he quickly became one of the most dangerous inmates after nearly killing one prisoner with a baseball bat—the victim had made the mistake of cracking wise about Cook’s eye. After his release from prison, Cook wandered around the United States by hitchhiking, an American pastime that romanticized the freedom of the open road. But Cook’s hatred of humanity led to a series of kidnappings and murders. The most violent of his crimes took place on a lonely stretch of highway in Oklahoma. Cook waved down motorist Carl Mosser, who, along with his wife Thelma and their three children, were forced at gunpoint to drive Cook around the southwest before their nightmarish trip ended in Arkansas. Cook murdered the entire family, along with the family dog, and dumped their bodies into an abandoned mine shaft. However, he left behind enough evidence that the authorities were closing in. His crimes continued until he kidnapped two hunters and forced them to drive across the border to Santa Rosalía. Cook planned to hide in Mexico, but a local police chief, Francisco Morales, recognized him. Morales unceremoniously approached him, snatched the gun from his belt, and placed him under arrest. Cook’s apprehension made sensational headlines, and he was executed in the gas chamber in 1952.

Originally titled The Cook Story, Lupino worried initially that her film would draw too much attention to the film’s production, not only because Billy Cook was a controversial topic, but because she was a woman directing an all-male cast. Fearing that the production would undo The Filmmakers, she proceeded with caution. She thought it was only fair to visit Cook in prison prior to his execution, and after acquiring special permission from her connections at the FBI to enter San Quentin for a meeting, she received Cook’s consent to film his story for $3,000, paid to his attorney. However, the film received pushback from the Production Code Administration (PCA), which protested in a letter against “any such attempt to glorify this wholesale murderer.” The Filmmakers wrote back, assuring that Cook would be a “symbol of evil” and their film would have documentary value, arguing they “have found that when dealing in facts we can produce pictures of greater import and impact.” Nevertheless, the PCA objected against Cook’s story as a violation of the Code, which states, “No picture shall be approved dealing with the life of a notorious criminal of current or recent times.” Lupino and Young soon rewrote and fictionalized their script to appease the PCA, although several similarities to the Cook case remain, from Myers’ deformed eyelid to the basic trajectory of his ride across the southwest.

Originally titled The Cook Story, Lupino worried initially that her film would draw too much attention to the film’s production, not only because Billy Cook was a controversial topic, but because she was a woman directing an all-male cast. Fearing that the production would undo The Filmmakers, she proceeded with caution. She thought it was only fair to visit Cook in prison prior to his execution, and after acquiring special permission from her connections at the FBI to enter San Quentin for a meeting, she received Cook’s consent to film his story for $3,000, paid to his attorney. However, the film received pushback from the Production Code Administration (PCA), which protested in a letter against “any such attempt to glorify this wholesale murderer.” The Filmmakers wrote back, assuring that Cook would be a “symbol of evil” and their film would have documentary value, arguing they “have found that when dealing in facts we can produce pictures of greater import and impact.” Nevertheless, the PCA objected against Cook’s story as a violation of the Code, which states, “No picture shall be approved dealing with the life of a notorious criminal of current or recent times.” Lupino and Young soon rewrote and fictionalized their script to appease the PCA, although several similarities to the Cook case remain, from Myers’ deformed eyelid to the basic trajectory of his ride across the southwest.

Using the story to create a tense, efficient thriller that barely reaches feature-length status at 71 minutes, Lupino and Young’s script functions as a chamber piece, only the chamber moves along miles of empty road. The dialogue is terse and brutal. Myers threatens his two captives with lines like “You wanna be all over that windshield?” or later “You two are gonna die and that’s all. It’s just a matter of when.” And the audience knows that Myers means business because the first few minutes of The Hitch-Hiker show his dirty work against the opening credits. Lupino keeps the camera low to the ground, watching Myers below the shoulders so the actual crimes can take place off-screen. In short succession, Myers murders a young couple in a convertible, followed by another man who stops to give him a ride. Nicholas Musuraca, who had worked with producer Val Lewton on Cat People (1942) and directors like Robert Siodmak on The Spiral Staircase (1946) and Jacques Tourneur on Out of the Past (1947), shot The Hitch-Hiker. Musuraca was contracted talent at RKO, which would distribute the film, and his use of shadow creates a memorable first appearance for Talman. His character emerges from the darkness of the back seat to reveal a threatening glower and a stark shadow cut across his face on the same side as his warped eyelid. And although this initial scene takes place at night, much of the story unfolds inside the car during the daytime, in frightening clarity, with Myers in the back seat, his gun trained on Bowen and Collins. It’s as though the specter had come out of the shadows and become real.

The Hitch-Hiker feels spare and pitless, set against jagged rocks and the Mexican landscape. The heat and sweat are just as ever-present as the threat of death from the monster holding Bowen and Collins at gunpoint. Myers not only barks orders and controls their every movement, but he calls them “soft” and exposes their fear and helplessness. They make a few breathless stops along the way, including a Mexican grocery store, while other stops seem to be veiled references to Cook’s crimes—such as the mineshaft where the three men have a meal or the dog that Myers shoots at a filling station. When they camp out at night, they fear any attempt at escape; Myers’ eyelid remains open, and they never know if he’s sleeping or watching them. In another film, the men would eventually retaliate and finally gain the upper hand over their captor, but Lupino is interested in showing them trapped and powerless. Instead, in a rare display of Mexican representation devoid of the usual Hollywood stereotypes of the era, the Mexican authorities arrange a sting and detain Myers. Meanwhile, Bowen and Collins never become heroes, and their only taste of revenge comes when Collins, who rallies against captivity even more than his friend, beats the captured Myers in an outburst of suppressed rage. In the end, order is restored with Myers’ arrest, but Bowen and Collins must return to their thankless lives, shaken by their ordeal.

Visually, Lupino’s aesthetic approaches realism with sometimes striking, expressive flourishes, aligning with a new postwar style adopted by many renegade filmmakers. The late 1940s launched an era in which many directors shot away from soundstages, including Jules Dassin (The Naked City, 1948), John Huston (The Asphalt Jungle, 1950), and Samuel Fuller (Pickup on South Street, 1953). At the same time that Italian Neorealists headed into the streets to capture a slice of reality by shooting on location, Lupino, too, was filming on actual highways and desert terrain. Her innovations in this arena go somewhat overlooked, but they suggest, as the story of The Hitch-Hiker does, that the real world is a place riddled with crime and death and unfairness. Films such as this present a shocking alternative view to the fantasized worlds created by Hollywood productions with pristine lighting and impeccably designed interiors. They feel more realistic than a studio confection. Lupino’s film takes place on barren lands, far away from the concrete and steel of the American metropolis, and seemingly even farther away from the track housing of the emergent suburbia. But Lupino’s compositions sometimes veer into heightened imagery at a crucial moment as well, shaking the viewer out of the real-world presentation. More than any other film in her career, The Hitch-Hiker strikes a balance between images captured in the real world and nightmarish noir scenes.

Visually, Lupino’s aesthetic approaches realism with sometimes striking, expressive flourishes, aligning with a new postwar style adopted by many renegade filmmakers. The late 1940s launched an era in which many directors shot away from soundstages, including Jules Dassin (The Naked City, 1948), John Huston (The Asphalt Jungle, 1950), and Samuel Fuller (Pickup on South Street, 1953). At the same time that Italian Neorealists headed into the streets to capture a slice of reality by shooting on location, Lupino, too, was filming on actual highways and desert terrain. Her innovations in this arena go somewhat overlooked, but they suggest, as the story of The Hitch-Hiker does, that the real world is a place riddled with crime and death and unfairness. Films such as this present a shocking alternative view to the fantasized worlds created by Hollywood productions with pristine lighting and impeccably designed interiors. They feel more realistic than a studio confection. Lupino’s film takes place on barren lands, far away from the concrete and steel of the American metropolis, and seemingly even farther away from the track housing of the emergent suburbia. But Lupino’s compositions sometimes veer into heightened imagery at a crucial moment as well, shaking the viewer out of the real-world presentation. More than any other film in her career, The Hitch-Hiker strikes a balance between images captured in the real world and nightmarish noir scenes.

The degree to which Lupino injected her commentary into otherwise “B” grade productions has been the subject of scholarly debate since the earliest writers of feminist and auteurist film theory first tried to affix a label onto her career. Given her significant role as a woman director, some writers have called her an essential feminist filmmaker; others feel her legacy belongs to the Hollywood mainstream and does not distinguish itself; others still recognize her films as the products of a distinct authorial voice. Among the dissenters is Andrew Sarris, who popularized the Auteur Theory in his book The American Cinema: Directors and Directions: 1929-1968. Sarris unceremoniously dismissed Lupino’s work, writing that her films “express much of the feeling if little of the skill which she has projected so admirably as an actress.” But then, this is a scholar who, as Scheib noted, also wrote that “directing is no job for a lady” in reference to Lillian Gish’s sole effort behind the camera in 1920, Remodeling Her Husband. Elsewhere, second-wave feminists such as Molly Haskell took a similarly harsh view, calling Lupino’s films “conventional, even sexist.” Debra Weiner, who interviewed Lupino in the 1970s for the critical anthology Women and the Cinema, described her films as “more reinforcing of 1950s ideology than undercutting it.” As a result, many insist Lupino’s point of view is “anti-feminist” given the sympathies she often expresses toward her male characters, above all Edmond O’Brien’s titular character in The Bigamist. Moreover, her detractors, and even her supporters, cite The Hitch-Hiker as a problem in her oeuvre, because its male cast does not invite discussion of the woman’s point of view.

But The Hitch-Hiker remains distinct as a film of 1953 because it challenges social conventions, not the least of which is the masculine ideal—a form of feminist perspective that many of Lupino’s critics would either overlook or altogether dismiss. Although The Bigamist offers a deeply cynical portrait of domestic life and conventional marriages, The Hitch-Hiker subverts the American Dream by uncovering the ugly reality underneath in the same manner as Alfred Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt (1943) and Orson Welles’ The Stranger (1946). She destabilizes the American family by suggesting Collins and Bowen, two otherwise loyal husbands, need to escape their wives for a sordid trip to Mexico. She questions the romantic pastime of hitchhiking by exposing the real-life killer who used America’s highways as his hunting grounds. And she shows the American police as disorganized and not always capable of catching the bad guy. Telling this story from a woman’s perspective in the 1950s, Lupino herself elevates the film’s brutal worldview by being an example of domestic nonconformity. In the postwar era, women had been relegated back to their roles as homemakers and constrained to domesticity. Lupino, meanwhile, did the opposite by forming her own company and making films about confronting subjects, all while maintaining a marriage and having children. Even after 1953, when her run of features came to halt, she continued directing episodes of television shows from Alfred Hitchcock Presents, The Twilight Zone, and The Untouchables, and almost exclusively in genres coded as masculine (adventures, thrillers, Westerns, etc.).

Writers, especially third-wave feminists, have lamented that Lupino did not neatly align with the values of intersectionality and gender positivity associated with the movement. Lupino’s films do not conform to the “Girl Power” mindset of the 1990s for what should be obvious reasons. For one, in the 1950s, Lupino’s experience was entirely unique. She was the sole woman in the Director’s Guild, and as such, she was required to maneuver through a male-dominated industry and adopt a certain gendered balance to survive. If she were perceived as a crusader for women, she might find herself ousted. She had to seem like just one of the guys behind the camera and when working with decision-makers, while also appearing ladylike and appropriately feminine to journalists and publicity departments. This required a level of self-control and image-making that is perhaps only slightly less an issue for today’s women directors. Even so, many feminists struggle with Lupino’s work because she does not immediately register as feminist; she had to weave her woman’s gaze into her films using subtle and sometimes unappreciated methods. But Lupino’s career does offer one significant study of womanhood and sisterhood as part of the surface text. Her final film, The Trouble with Angels, starring Rosalind Russell and Haley Mills, came in 1966, and it centers on a group of young women in a Catholic boarding school. It’s her most outspokenly feminist film, questioning the place of faith, career ambition, domestic roles, and sexuality in the lives of then-modern women.

Writers, especially third-wave feminists, have lamented that Lupino did not neatly align with the values of intersectionality and gender positivity associated with the movement. Lupino’s films do not conform to the “Girl Power” mindset of the 1990s for what should be obvious reasons. For one, in the 1950s, Lupino’s experience was entirely unique. She was the sole woman in the Director’s Guild, and as such, she was required to maneuver through a male-dominated industry and adopt a certain gendered balance to survive. If she were perceived as a crusader for women, she might find herself ousted. She had to seem like just one of the guys behind the camera and when working with decision-makers, while also appearing ladylike and appropriately feminine to journalists and publicity departments. This required a level of self-control and image-making that is perhaps only slightly less an issue for today’s women directors. Even so, many feminists struggle with Lupino’s work because she does not immediately register as feminist; she had to weave her woman’s gaze into her films using subtle and sometimes unappreciated methods. But Lupino’s career does offer one significant study of womanhood and sisterhood as part of the surface text. Her final film, The Trouble with Angels, starring Rosalind Russell and Haley Mills, came in 1966, and it centers on a group of young women in a Catholic boarding school. It’s her most outspokenly feminist film, questioning the place of faith, career ambition, domestic roles, and sexuality in the lives of then-modern women.

If The Hitch-Hiker can be called feminist, then this label flows from a recurring theme in Lupino’s work—her critique of society’s need to maintain traditional gender roles and institutional normalcy, even if it means the loss of individuality. Her characters often find themselves tortured by these social pressures, revealing something rotten about postwar American idealism. Given her interest in unexceptional people marred by aspects of American life deemed taboo by the mainstream, Martin Scorsese called her work “resilient with a remarkable empathy for the fragile and broken hearted.” Lupino is a filmmaker who is rediscovered and reassessed by every generation, though her significant place in film history remains constant. And though her authorship and feminist perspective continue to be debated, let it be said that her individuality, ability to navigate the male-dominated industry, and status as an independent woman filmmaker render her uncommon. With The Hitch-Hiker, Lupino shows no outward desire to deliver a sociological soapbox; she allows viewers to accept her work as a straightforward and single-layered thriller. On those terms, it functions exceptionally. But not unlike Lupino herself, the film walks the fine line between conformity and independence.

Bibliography:

Anderson, Mary Ann, and Ida Lupino. Ida Lupino: Beyond the Camera: 100th Birthday Special Edition. BearManor Media, 2018.

Georgakas, Dan. “Ida Lupino: Doing It Her Way.” Cinéaste, vol. 25, no. 3, 2000, pp. 32–36. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41689260. Accessed 20 Aug. 2020.

Grisham, Therese, and Julie Grossman. Ida Lupino, Director: Her Art and Resilience in Times of Transition. Rutgers University Press, 2017.

Kuhn, Annette, editor. Queen of the ‘B’s: Ida Lupino Behind the Camera. Praeger, 1995.

Scheib, Ronnie. “Ida Lupino: Auteuress.” Film Comment, vol. 16, no. 1, 1980, pp. 54–64. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43455621. Accessed 20 Aug. 2020.

Weiner, Debra. “Interview with Ida Lupino.” Women and the Cinema. Edited by Karyn Kay and Gerald Peary. Dutton, 1977, pp. 169-178.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review