The Definitives

The Godfather (1972)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Myths examine origins and establish traditions, and a rich mythology sustains The Godfather. Since debuting in 1972, writers and viewers have tried to encapsulate what makes the film a watershed moment in cinema history. Based on Mario Puzo’s best-selling gangster epic, the film explores connections between fathers and sons, family bonds and brutal violence, the American Dream and capitalist greed. The story has seeped into our collective consciousness, creating a mystique around the Corleones, an Italian-American crime family, and the dramatized transition of power in their ranks. Our compulsion to keep examining the phenomenon—investigating why the film is so compelling and, in doing so, adding to the overwhelming degree of assessment—only feeds its status in the pantheon of great filmmaking and storytelling. Countless words have been written to analyze director Francis Ford Coppola’s filmmaking techniques, celebrate the incredible performances, chronicle the behind-the-scenes conflict, survey its influence on the gangster genre, and situate the film in historical contexts. And writers will devote many more words to the subject, all in hopes of understanding why it continues to have a lasting impact more than most other films. The persistent fascination with The Godfather and its unchartable reach has ingrained its mythological place in our culture and history.

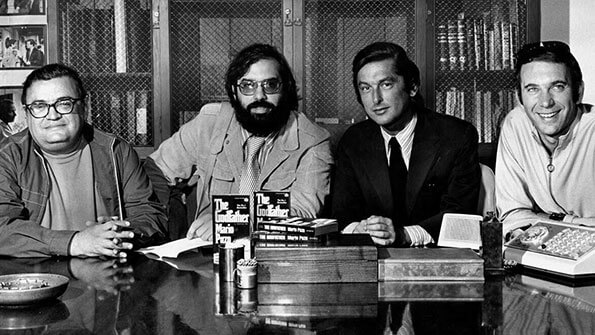

So how did the film become the stuff of Hollywood legend? Everyone involved in the production, from Puzo to Coppola to actors with minor roles in the cast, has given their account of The Godfather. There’s a legacy of storytelling about the film among those involved—what it was like to watch Marlon Brando work, witness the arrival of Al Pacino, and be on the set while the battle between Paramount Pictures and Coppola exploded. Given its eventual monumental success at the box office and 1973 Oscar ceremony, which ultimately saved Paramount from going under, everyone has an opinion about who did what and where it all started. Everyone wants credit, too. The answer to the question “Who or what is responsible for this masterpiece?” remains a subject of some debate, exaggerated by the desire to give the majority of credit to a single person. Robert Evans, then the head of production at Paramount, is usually named as an integral force behind the camera. Others attribute the film’s success to Coppola, the 32-year-old Hollywood outsider whose singular vision, and willingness to fight for that vision, shaped the resulting three-hour film. But pour over any number of books and articles about The Godfather, and so many details remain unclarified, occasionally misrepresented, and often disputed by those involved. Historians and critics have taken down conflicting accounts from the principal parties and witnesses, leaving viewers without a clear picture, catapulting the film into the realm of myth.

The exhaustive accounts of the film’s development from page to screen might threaten to overshadow another film, except The Godfather also lends itself to layered textual and thematic analyses. It’s not a classically told story, after all, and it’s easy to overlook how unconventional Coppola’s approach was considered at the time, given its high ranking today on many lists of the greatest films ever made (AFI, BFI, et al.). The novelty of its aesthetic in 1972 has been taken for granted in the subsequent decades. Though it comes out of the venerable gangster movie tradition, it deviates from the classical template established during Hollywood’s Golden Age. Such films dramatized Prohibition-era controversies and created thin allusions to figures such as Al Capone. A long list of gangster classics from the early sound era—The Public Enemy and Little Caesar (both in 1931), Scarface (1932), Angels with Dirty Faces (1938), and The Roaring Twenties (1939) among them—solidified the genre with sensationalized stories ripped from the headlines, featuring larger-than-life performances from James Cagney, Edward G. Robinson, and George Raft. The genre resurfaced in postwar years, extended by film noir, when gangsters became less ethnically specific (Caucasian but not Italian) and concentrated on their warped psychology, such as Cagney’s mad robber in White Heat (1949). There would be few innovative leaps in the genre in the decades to follow. Like Westerns or swashbucklers, the gangster movie became another form of studio programmer: predictable, safe, and easy to sell.

Consider Martin Ritt’s The Brotherhood, a mafia tale starring Kirk Douglas, released by Paramount in 1968. It’s a boilerplate gangster production of the era, notable for its superficial similarities to The Godfather: both involve a veteran who returns home from war only to find himself involved in the family’s criminal organization; both feature an extended wedding sequence (though decidedly smaller scale in Ritt’s film), establishing the main characters and conflicts that will play out for film’s duration; both also entail a character who, after killing the competition, heads to the Sicilian homeland in exile. Not only did The Brotherhood receive tepid reviews and box-office receipts, but its commercial failure translated to skepticism about any film project concerning the Italian mob or organized crime. “Sicilian mobster films don’t play,” Paramount’s distribution department told Evans, remembering other duds such as Black Hand (1950). They considered the gangster genre dead—exhausted from overuse like the Western would soon become—and refused to consider future projects until Puzo’s book became a nationally recognized bestseller. However, the shared beats between the two films underscore the texture of Puzo’s novel and how unconventional Coppola’s treatment of such well-established material would be.

Consider Martin Ritt’s The Brotherhood, a mafia tale starring Kirk Douglas, released by Paramount in 1968. It’s a boilerplate gangster production of the era, notable for its superficial similarities to The Godfather: both involve a veteran who returns home from war only to find himself involved in the family’s criminal organization; both feature an extended wedding sequence (though decidedly smaller scale in Ritt’s film), establishing the main characters and conflicts that will play out for film’s duration; both also entail a character who, after killing the competition, heads to the Sicilian homeland in exile. Not only did The Brotherhood receive tepid reviews and box-office receipts, but its commercial failure translated to skepticism about any film project concerning the Italian mob or organized crime. “Sicilian mobster films don’t play,” Paramount’s distribution department told Evans, remembering other duds such as Black Hand (1950). They considered the gangster genre dead—exhausted from overuse like the Western would soon become—and refused to consider future projects until Puzo’s book became a nationally recognized bestseller. However, the shared beats between the two films underscore the texture of Puzo’s novel and how unconventional Coppola’s treatment of such well-established material would be.

Coppola should be credited for keeping one foot of The Godfather in traditional motifs and another foot outside them. He stood at the front of New Hollywood’s line of young upstarts—including Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorsese, and Brian De Palma—who trained at schools like USC and UCLA during the 1960s. Movie brats all, they set out to revitalize Hollywood by working within studios to overcome the stodgy and safe products of the era. In his twenties, Coppola started out making skin flicks for experience before advancing into B-grade horror (Dementia 13, 1963), a maligned musical (Finian’s Rainbow, 1968), and a road movie (The Rain People, 1969). Coppola foundationalized his rebellious spirit with American Zoetrope in 1969, his San Francisco-based production company founded to give young film artists the freedom to experiment with the medium. Their first production, George Lucas’ THX 1138 (1971), an artfully conceived commercial flop, signaled the company’s ongoing struggle to remain in the black. Coppola needed the occasional studio job to pay the bills—and keep the sheriff from locking the doors, according to Coppola in an oft-told story. He took a studio gig co-writing Patton (1970) alongside Edmund H. North, which not only earned him an Oscar but helped legitimize him in the eyes of studio brass.

Around the same time in 1969, Mario Puzo’s best-selling book, originally titled Mafia, had become an instant phenomenon, selling upwards of nine million copies in the years after its publication. Puzo, a gambling addict and struggling writer, had already published several novels and short stories, some well-reviewed but none of them good sellers. At 45, he was in debt and had grown tired of writing books that no one read, so he decided to follow his editor’s advice and write a Mafia story in a pulpy style proven to sell: larger-than-life characters, sex or violence every few pages, and multiple plotlines to ensnare the reader. Puzo based Don Vito Corleone on his mother, drawing famous lines such as “Make him an offer he can’t refuse” directly from his mother’s mouth. But this is a disputed detail. Some accounts say a mobster used the line, and Puzo’s mother borrowed it. Nevertheless, his eventual manuscript became a sensation, earning Puzo a whopping $410,000 for the paperback rights alone—a record that many attribute to the highly publicized appearance of Mafia enforcer Joseph Valachi before Congress in 1963, watched by millions of Americans on television. Valachi’s testimony—complete with gems like, “You live by the gun and by the knife, and you die by the gun and by the knife”—exposed the general public to their first hint of Italian-American organized crime. Valachi also underscored a certain mythic romanticism about the Mafia that Puzo worked into his book, which weaves a yarn about a Sicilian family who pursues the American Dream by any means at their disposal. For readers who struggled to get what they wanted in life and saw corrupt systems of government and capitalism all around them, the Corleones had a distinct appeal in their self-governance and enforceable moral code.

Coppola establishes the thematic heart of The Godfather in the first scene. His screenplay differs from Puzo’s book, which opens in a courtroom with Italian-American undertaker Bonasera watching as his daughter’s rapists receive suspended sentences, followed by a passage in Los Angeles featuring Johnny Fontane. By contrast, the film opens in Don Vito Corleone’s home office, a dark interior of browns and muddy blacks, sparsely illuminated by overhead lighting and some faint rays through the blinds. It’s an appropriate setting for shady business. Bonasera (Salvatore Corsitto) faces the Don (Brando) and begins a speech, “I believe in America.” But he means to say that America has failed him, so he has come to ask Don Vito for the “justice” that the American system cannot give. And on this special occasion, as Tom Hagen (Robert Duvall), the family consigliere, explains, “No Sicilian can refuse any request on his daughter’s wedding day.” Though Don Vito insists “we’re not murderers” to Tom, the rapists will be brought to justice, just not by Vito or Tom’s hands. It’s this subtle distinction that helps Don Vito sleep at night. The scene also features Coppola alternating between Don Vito’s tense office meetings, the stuff of grave seriousness, and the wedding celebrations outside, filmed in splendid daylight with brightly colored dresses and lively partying: Don Vito’s two older sons, Sonny (James Caan) and Fredo (John Cazale), unwind with casual sex and booze respectively, while his youngest, Michael (Pacino), donning his military uniform, explains to Kay (Diane Keaton), his Irish-Catholic girlfriend, “That’s my family, Kay. That’s not me.”

Coppola establishes the thematic heart of The Godfather in the first scene. His screenplay differs from Puzo’s book, which opens in a courtroom with Italian-American undertaker Bonasera watching as his daughter’s rapists receive suspended sentences, followed by a passage in Los Angeles featuring Johnny Fontane. By contrast, the film opens in Don Vito Corleone’s home office, a dark interior of browns and muddy blacks, sparsely illuminated by overhead lighting and some faint rays through the blinds. It’s an appropriate setting for shady business. Bonasera (Salvatore Corsitto) faces the Don (Brando) and begins a speech, “I believe in America.” But he means to say that America has failed him, so he has come to ask Don Vito for the “justice” that the American system cannot give. And on this special occasion, as Tom Hagen (Robert Duvall), the family consigliere, explains, “No Sicilian can refuse any request on his daughter’s wedding day.” Though Don Vito insists “we’re not murderers” to Tom, the rapists will be brought to justice, just not by Vito or Tom’s hands. It’s this subtle distinction that helps Don Vito sleep at night. The scene also features Coppola alternating between Don Vito’s tense office meetings, the stuff of grave seriousness, and the wedding celebrations outside, filmed in splendid daylight with brightly colored dresses and lively partying: Don Vito’s two older sons, Sonny (James Caan) and Fredo (John Cazale), unwind with casual sex and booze respectively, while his youngest, Michael (Pacino), donning his military uniform, explains to Kay (Diane Keaton), his Irish-Catholic girlfriend, “That’s my family, Kay. That’s not me.”

During the 30-minute wedding sequence, Coppola shows Vito looking out from his window through the blinds at the party. The shots establish the relationship between business and the family, how they are inextricably connected, in that one allows the other to flourish—albeit through a juxtaposition of entrenched family values and criminal acts. But the shots of Vito gazing longingly out at his daughter’s wedding suggest his business dealings have torn him away from his family. The racketeering and coercion that goes on behind closed doors is a means to an end, a way for Vito to “take care of my family.” Though Vito is a ruthless criminal, he also cherishes his loved ones. He would prefer to be savoring his time with them. To illustrate this, Coppola gives us moments of Vito’s adored role in his family—his fathering of Fredo to “be a man,” his strategic advice to Michael, his tender last scene with his grandson. Vito understands the careful balance between his two worlds. But later in the film, after Vito’s near assassination, after Michael rises to become head of the family, the family-business dichotomy becomes unbalanced. The criminal enterprise has consumed Michael, whose ruthless approach to business has sidelined everything else. Of course, Michael’s severity comes as a response to his family’s war with the Five Families over heroin and casinos, which has claimed Sonny and nearly his father. But his scorched earth approach to protecting the family consumes him, leaving his family secondary to the criminal enterprise.

After Coppola read Puzo’s book for the first time, he found himself attracted to the story for several reasons. The portrait of a mob family proved compelling to the Italian-American director, who could imagine what the Corleones must be like in vivid detail. He also recognized the innate classicism that would propel the story into cinematic mythology, given its hints of Shakespeare’s King Lear, complete with three sons as potential successors. More significantly, Puzo’s text as a metaphor for American capitalism attracted Coppola. If the American Dream once represented the average citizen’s freedom to enrich one’s family by getting a fair chance to prosper, it had since been bulldozed by corporate interests, corrupt politicians, and crimes against justice. “The real appeal of the movie was showing family ties in a setting of power,” screenwriter Robert Towne told The New Yorker. “It was really kind of reactionary in that sense—a perverse expression of a desirable and lost cultural tradition, filling people with longing for a family like that, a father who not only knew what was best but, if a guy was giving you a hard time, could have someone kill him.” When the American Way proved faulty, the Corleones had the influence and will to correct it for people like Bonasera. In business, they were self-starters, a paragon of entrepreneurism. But when negotiations failed, gangsters could back their drive for success with the brutality required to ensure it. Americanism was rarely purer in its all-consuming need to conquer, own, and consume ad infinitum.

The Godfather dramatizes how the American Dream has failed, leaving only raw capitalism, epitomized by the brutality of the Corleones under Michael. If the family under Don Vito represents the fantasy of having the power to enforce the American Dream, criminally achieved though it may be, the family under Michael sacrifices familial solidarity for corporate greed and stability. Don Vito understood the criminal enterprise served the family, which must be protected and appreciated. Michael turns the family business from a mom-and-pop shop to a corporation bent on mergers and acquisitions—not unlike Gulf+Western, the conglomerate that purchased Paramount in 1966. The film in Coppola’s hands, then, reveals that the dog-eat-dog nature of American capitalism has literally closed the door on the family. Coppola shows this twice: first when Michael shuts the phone booth door on Kay, who must stand in the cold outside while he learns of the attempted assassination on his father; second, in the famous final shot, when Michael’s office door shuts on Kay, creating a permanent barrier between the two. The film shows that not even the Corleone family can survive capitalist greed. The family unit endures, to be sure. But it’s at the cost of love, trust, and everything that made the family so appealing under the rule of Don Vito. At every step, Michael transforms the Mafia from a gentleman’s agreement among the family leaders to a coolly negotiated series of hostile takeovers by an organization that may as well be called Corleone Industries.

The Godfather dramatizes how the American Dream has failed, leaving only raw capitalism, epitomized by the brutality of the Corleones under Michael. If the family under Don Vito represents the fantasy of having the power to enforce the American Dream, criminally achieved though it may be, the family under Michael sacrifices familial solidarity for corporate greed and stability. Don Vito understood the criminal enterprise served the family, which must be protected and appreciated. Michael turns the family business from a mom-and-pop shop to a corporation bent on mergers and acquisitions—not unlike Gulf+Western, the conglomerate that purchased Paramount in 1966. The film in Coppola’s hands, then, reveals that the dog-eat-dog nature of American capitalism has literally closed the door on the family. Coppola shows this twice: first when Michael shuts the phone booth door on Kay, who must stand in the cold outside while he learns of the attempted assassination on his father; second, in the famous final shot, when Michael’s office door shuts on Kay, creating a permanent barrier between the two. The film shows that not even the Corleone family can survive capitalist greed. The family unit endures, to be sure. But it’s at the cost of love, trust, and everything that made the family so appealing under the rule of Don Vito. At every step, Michael transforms the Mafia from a gentleman’s agreement among the family leaders to a coolly negotiated series of hostile takeovers by an organization that may as well be called Corleone Industries.

Puzo’s book attracted Peter Bart initially. A former journalist turned Paramount executive, Bart first optioned Puzo’s story for $12,500 before its publication. Before being selected as Paramount’s production head, Evans also specialized in nabbing literary properties for screen adaptation. But Evans glosses over Bart’s role in discovering Puzo’s book in his 1994 memoir, The Kid Stays in the Picture. For Evans, The Godfather was the latest in his line of best-selling literary acquisitions that included Roderick Thorpe’s The Detective, Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby, and Erich Segal’s Love Story—all made into profitable films. Evans even claims he met with Puzo before the book’s publication and agreed to pay the author’s gambling debts in exchange for the film rights, going so far as to give Puzo an office at Paramount to finish his manuscript. But the extent of these claims has since been disputed as Evans trying to make himself appear as the film’s mastermind. Some accounts give Puzo’s publisher or members of the mob credit for keeping the author afloat financially while he researched the book.

Regardless, Evans and Bart approached a long list of directors for the eventual adaptation. The candidates, ranging from Arthur Penn to Costa-Govras, either dismissed the material on moral grounds or, like “Bloody” Sam Peckinpah (The Wild Bunch, 1969), focused too much on the pulpier aspects and not enough on the multiple dimensions of the narrative. Then, Evans and Bart sought to make the story as authentic as possible by enlisting an Italian-American director, and Coppola’s name came up. Evans recognized that Coppola would be cheap, and what’s more, “He knew the way these men in The Godfather ate their food, kissed each other, talked. He knew the grit.” Then again, Bart has since denied claims that they chose Coppola because of his ethnicity. He told The New Yorker, “The thing was that Francis was not the only Italian-American director I knew but the brightest young director I knew.” Like most aspects of The Godfather, the motivations that led to Coppola’s entry into the project vary, depending on the source. Not only did Bart sell Evans on Coppola by playing up the young director’s Italian heritage in contrast to the predominantly Jewish filmmakers behind The Brotherhood, but he also underscored how, if Evans wanted to make the film, he would have to act fast to undercut Burt Lancaster’s production company from tempting Paramount with a million-dollar offer for the rights.

For Coppola’s part, he has since confirmed that he eventually signed on to direct The Godfather out of necessity to keep American Zoetrope operating, marking his career-long struggle to balance commercial demand with personal ambitions. The Godfather and its sequel allowed him to direct subsequent passion projects he would have never been able to shoot had his adaptation of Puzo’s book not been such a colossal moneymaker. But his lasting antagonism toward studio authority and string of subsequent flops resulted in Coppola having to spend more of his career realizing commercial productions than his artistic ambitions. At first, he turned down Bart’s offers to direct. Coppola had started to read the much-talked-about book, only to dismiss the text as trash for all its talk of bloody violence and large sexual organs (Sonny’s enormous penis and his mistress’ cavernous vagina to match). Lucas had pleaded with Coppola to read The Godfather in full, but it wasn’t until Coppola realized how popular the book was that he committed himself to a complete readthrough. Then, finally, he saw its potential as a story about family drama and a metaphor for capitalism in America.

For Coppola’s part, he has since confirmed that he eventually signed on to direct The Godfather out of necessity to keep American Zoetrope operating, marking his career-long struggle to balance commercial demand with personal ambitions. The Godfather and its sequel allowed him to direct subsequent passion projects he would have never been able to shoot had his adaptation of Puzo’s book not been such a colossal moneymaker. But his lasting antagonism toward studio authority and string of subsequent flops resulted in Coppola having to spend more of his career realizing commercial productions than his artistic ambitions. At first, he turned down Bart’s offers to direct. Coppola had started to read the much-talked-about book, only to dismiss the text as trash for all its talk of bloody violence and large sexual organs (Sonny’s enormous penis and his mistress’ cavernous vagina to match). Lucas had pleaded with Coppola to read The Godfather in full, but it wasn’t until Coppola realized how popular the book was that he committed himself to a complete readthrough. Then, finally, he saw its potential as a story about family drama and a metaphor for capitalism in America.

Not everyone was convinced about Coppola. The director had to sway the film’s producer Al Ruddy in a legendary pitch meeting where Coppola stood atop a table, shouted, and sold his vision of The Godfather. Ruddy compared him to the conman Bill Starbuck in the play The Rainmaker, promising to bring rain in a drought. Unlikely though it may have seemed, Coppola, like Starbuck, made it rain, but only after convincing the studio to spend more than they wanted. Paramount chose to situate the story in a contemporary setting as a money-saving measure. Period costumes and cars would increase the budget significantly, from the intended low-budget production to a significant investment. Paramount was, after all, a struggling studio. “There were eight studios in Hollywood and Paramount was ninth,” Evans wrote in his autobiography. But Coppola convinced them to shift the settings to the late 1940s and 1950s, along with location shooting in New York. It might be tempting to give Paramount praise for trusting in the maverick director and forking out the budgetary dollars for his vision—production costs rose well above the initially estimated $2.5 million—but Evans and others at the studio also mistrusted Coppola, spied on him, and on more than one occasion, tried to get him fired from the production. In Mark Seal’s book about the film, Leave the Gun, Take the Cannoli, he discovered the film materialized out of “an unlikely amalgamation of brute force, artistic choice, market necessity, genius, and dumb luck.” Part of what makes The Godfather so mythological is that it ever got made.

As already noted, given how thoroughly The Godfather has saturated pop culture, it’s easy to miss how much of the production was considered unorthodox at the time. Take the cast, headlined by Brando, the down-on-his-luck actor whose erratic behavior and string of box-office disasters made him the odd man out in Hollywood. Puzo always saw Brando in the role and reached out to him well in advance of the production to ask if he would play Don Vito, though the actor turned down the part—at first, anyway. Al Pacino was a veritable unknown performer on the New York stage, appearing only in The Panic in Needle Park (1971) on film. Diane Keaton was best known for a television commercial. At least, James Caan and Robert Duvall had several credits to their name, and Coppola had seen their work on stage and screen. Brando, Pacino, Keaton, Caan, and Duvall always topped Coppola’s wishlist for the leading players, yet Evans and everyone else at Paramount recoiled at his picks. So the studio spent eight months and $400,000 on an elaborate casting call, the most highly publicized and widespread since David O. Selnick spared no expense to find his Scarlett O’Hara for Gone with the Wind (1939). Everyone who was anyone was considered, and many of them auditioned and screen-tested. But after all the rigamarole, Paramount, in time, agreed to the cast that Coppola wanted in the first place. In a story that continues to permeate Hollywood lore, Coppola eventually convinced the studio to cast Brando after recording a screen test—with shoe polish in his hair and tissues in his cheeks—showing how completely the actor disappeared into his role. If the casting process didn’t result in the studio finding a cast they approved of, the coverage helped publicize the upcoming film.

The real-life Mafia had their part to play in The Godfather’s journey to the screen as well, adding to the strange story of its making. Besides Puzo basing many of the book’s major killings on actual incidents, rumors and publicized dissent add to the film’s Mafia flavor. For instance, the claim that Evans paid Puzo’s gambling debt has been contradicted, suggesting the Mafia wrote off Puzo’s debt after reading the book, which they loved and later imitated. Most publicly, Mob boss Joe Colombo led an aggressive campaign against the production on behalf of the Italian-American Civil Rights League. Colombo and the League’s voters insisted that the production remove references to harmful stereotypes—namely, the words “Cosa Nostra” and “Mafia.” Ruddy moved to quiet their campaign against the film by announcing Paramount would donate the proceeds from the New York premiere to the League; he also offered members the chance to appear as extras in the film, and that calmed the opposition. Ultimately, Colombo’s vocal agenda caused the production all sorts of problems. But the trouble came to a halt with his attempted murder in June of 1971—a gangland hit reportedly orchestrated by boss Carlo Gambino. Colombo died seven years later, having never emerged from his coma. And then, many years after the film’s release, it would come out that Gulf+Western executive Charles Bluhdorn helped Sicilian mobster Michele “The Shark” Sindona—a gangster who would later be convicted of murder and die in prison from cyanide poisoning—back Paramount with millions of dollars in mob money by contributing to a shady Vatican bank. Doubtless, whispers of this informed Coppola and Puzo’s screenplay for The Godfather Part III (1990).

The real-life Mafia had their part to play in The Godfather’s journey to the screen as well, adding to the strange story of its making. Besides Puzo basing many of the book’s major killings on actual incidents, rumors and publicized dissent add to the film’s Mafia flavor. For instance, the claim that Evans paid Puzo’s gambling debt has been contradicted, suggesting the Mafia wrote off Puzo’s debt after reading the book, which they loved and later imitated. Most publicly, Mob boss Joe Colombo led an aggressive campaign against the production on behalf of the Italian-American Civil Rights League. Colombo and the League’s voters insisted that the production remove references to harmful stereotypes—namely, the words “Cosa Nostra” and “Mafia.” Ruddy moved to quiet their campaign against the film by announcing Paramount would donate the proceeds from the New York premiere to the League; he also offered members the chance to appear as extras in the film, and that calmed the opposition. Ultimately, Colombo’s vocal agenda caused the production all sorts of problems. But the trouble came to a halt with his attempted murder in June of 1971—a gangland hit reportedly orchestrated by boss Carlo Gambino. Colombo died seven years later, having never emerged from his coma. And then, many years after the film’s release, it would come out that Gulf+Western executive Charles Bluhdorn helped Sicilian mobster Michele “The Shark” Sindona—a gangster who would later be convicted of murder and die in prison from cyanide poisoning—back Paramount with millions of dollars in mob money by contributing to a shady Vatican bank. Doubtless, whispers of this informed Coppola and Puzo’s screenplay for The Godfather Part III (1990).

The Godfather’s screenplay, which Puzo started under Bart’s supervision, led to a working partnership between the author and Coppola, who took turns rewriting the other’s revisions. But the screenwriting process never quite ended. Coppola would produce rewrites sometimes the night before shooting, sometimes the same day. The actors improvised as well, creating some of the film’s most memorable and quotable dialogue. Caan invented Sonny’s “bada-bing” out of nowhere when he says, “You got to get them close like this and bada-bing! You blow their brains all over your nice Ivy League suit.” Today, the phrase Caan introduced into American vernacular has become synonymous with Tony Soprano, the complex personality from HBO’s watershed drama The Sopranos (1999-2007), a similar look into the private lives of gangsters. Playing Clemenza, Richard Castellano added the latter half to the famous line, “Leave the gun, take the cannoli,” supposedly on his wife’s suggestion—to emphasize the practicality of Clemenza putting food on the table for his family. The choice not only became iconic, but it underscores the film’s central theme of chronicling Italian-American families. Among the less fortunate improvisations was Pacino’s leap onto a moving car in the first week of filming, injuring his ankle and putting the production behind schedule.

Coppola’s endless rewriting, sometimes between setups, put the schedule in disarray. As a result, the budget rose over $6 million under Coppola, who insisted on doing things his way. For instance, Coppola wanted reality for the notorious scene where the Hollywood producer—who refuses to cast the Sinatra-esque Johnny Fontaine (Al Martino)—wakes up to a horse head in his bed. So the production designer, Dean Tavoularis, obtained the real thing from a dead horse slated for processing at a dog food company. By all accounts, choices like these worsened tensions between Coppola and the price-conscious studio, and some longtime filmworkers on the set turned against their director. Take Aram Avakian, the film’s first editor, who veritably spied on and badmouthed Coppola to the studio. Avakian aligned himself with Jack Ballard, a studio crony sent to New York by Paramount to monitor the production. Avakian suggested that the studio should fire Coppola and make him the replacement (he had a single directing credit). Hearing about this, Coppola fired Avakian before any such coup could occur. Only the scenes shot on location in Sicily, far from anyone loyal to the studio, brought Coppola any pleasure; every other day, Coppola was under enormous pressure and came to work expecting to be fired. But he wouldn’t quit, even if his anxieties were giving him nightmares. And worse, they were not unfounded anxieties. Bart and Evans met with Elia Kazan as a possible replacement, but nothing came of it. The director told film critic Michael Sragow in 1997, “It was just an awful experience. I’m nauseated to think about it.” It’s stories like these that turn The Godfather’s production into such an against-all-odds account and build the film’s mythical status.

The combination of spontaneity behind the scenes and Coppola’s vision adds to the sense that some strange alchemy was at work. Fortunately, Coppola had effectively created goodwill between the actors, who sat at family-style Italian dinners and bonded before the shoot began, and it came through in their performances. Everyone could tell that Brando’s presence as Don Corleone would be disquieting and brilliant. Pacino’s Michael was slow to materialize, convincing Evans and the studio brass that Coppola had made the wrong choice. But Pacino’s performance would reveal itself as an elaborate construction that builds gradually into a monumental turn. Elsewhere, for his film about the love of family, it only made sense that Coppola would cast his sister, Talia Shire, as Connie, the sole Corleone daughter. Coppola’s parents would make appearances as well. And it has since become a legend that his daughter Sofia made her screen debut as the son of Michael and Kay during the pivotal baptism scene—a rite cross-cut with Michael’s soldiers eliminating the heads of the warring mob families. Some questioned the extent of Coppola putting his understanding of Italian families into the film through his own. From the studio’s perspective, he was still the ambitious young upstart who refused to do things traditionally. Though, ironically, his capacity to depict an authentic Italian-American experience was one of the reasons the studio hired him—that is, depending on the account.

The combination of spontaneity behind the scenes and Coppola’s vision adds to the sense that some strange alchemy was at work. Fortunately, Coppola had effectively created goodwill between the actors, who sat at family-style Italian dinners and bonded before the shoot began, and it came through in their performances. Everyone could tell that Brando’s presence as Don Corleone would be disquieting and brilliant. Pacino’s Michael was slow to materialize, convincing Evans and the studio brass that Coppola had made the wrong choice. But Pacino’s performance would reveal itself as an elaborate construction that builds gradually into a monumental turn. Elsewhere, for his film about the love of family, it only made sense that Coppola would cast his sister, Talia Shire, as Connie, the sole Corleone daughter. Coppola’s parents would make appearances as well. And it has since become a legend that his daughter Sofia made her screen debut as the son of Michael and Kay during the pivotal baptism scene—a rite cross-cut with Michael’s soldiers eliminating the heads of the warring mob families. Some questioned the extent of Coppola putting his understanding of Italian families into the film through his own. From the studio’s perspective, he was still the ambitious young upstart who refused to do things traditionally. Though, ironically, his capacity to depict an authentic Italian-American experience was one of the reasons the studio hired him—that is, depending on the account.

Coppola worked with cinematographer Gordon Willis, nicknamed the “Prince of Darkness,” to create the film’s distinct visual schema of heavy shadows and businesslike sit-downs between Mafia families. But when Evans saw the initial footage, he couldn’t see anything. Willis’ photography had been too dark. The producer couldn’t understand Brando’s mumbled lines, either. The footage and performances were a disaster, according to Evans. The disappointing appearance of the initial dailies contributed to the producers turning on Coppola. Then again, this was Willis and Coppola’s plan. However unified, the director and cinematographer were not immune to conflict either, given the shouting matches that caused them to walk off the set or punch holes into doors. But if brightly colored Doris Day movies were the studio norm, Coppola wanted something different to represent the Corleones, who, on the surface, looked like an average American family. Behind closed doors, darker things were happening. Willis used overhead lighting to give the figures a theatrical quality. This highlighted the contrast between the bright wedding scenes and the darkened office to emphasize further the thematic conflict between light and dark, the exterior and the interior worlds. Indeed, the predominance of interiors implies the safety inside the family and the danger outside that awaits. Note that the assassination attempt of Don Vito occurs outside in the market.

Coppola and Willis instill a classicism into the look of The Godfather as well, which is why it doesn’t look like other films from the 1970s. The filmmaking represents an intricate application and unification of set design, camera placement, and lighting, arranged to make the Corleones look at once like a family but also players in a grand drama. Willis also insisted, whenever possible, on classical tableau shots that put the entire family on display—a family portrait in sfumato shadows and the amber hues of his underexposed film stock. Coppola and Willis’ visual agenda not only conveys a story that feels like history unfolding onscreen but also builds the narrative’s thematic underpinnings about the Mafia as a capitalist enterprise. In his monograph for the British Film Institute, Jon Lewis notes how Coppola stages sit-downs between family members like a corporate negotiation. Vito announces, with the cadence of an executive looking to broker a deal, “I hoped that we could come here and reason together. And as a reasonable man, I’m willing to do whatever’s necessary to find a peaceful solution to these problems.” The tactic makes these tableau scenes feel momentous, giving them the sense of a myth in the making. The same is true of scenes blocked around Michael, who wields a different strategy used by ruthless business people to control the room and subtly influence others. Michael isn’t his father’s outwardly humble businessman; he’s an unforgiving tactician bent on taking over the competition.

Regardless of Coppola and Willis’ entrenched visual and thematic organization, everyone on the studio side was telling Coppola that what he was doing was wrong and terrible. Only the occasional outsider boosted Coppola’s confidence that his instincts had produced something incredible. For example, when Coppola asked screenwriter Robert Towne to help write a scene between Don Vito and Michael to set the stakes, he showed the famed Hollywood script doctor and later Oscar-winner for Chinatown (1974) some early footage. Towne—who wrote the only scene that finds Don Vito and Michael conferring about business and family, a strategic piece of plotting and character building—was floored and told Coppola it was “amazing.” As for the final cut, Coppola turned in a version that ran just over two hours, following Evans’ warning that the studio would take the picture out of Coppola’s hands if it ran longer. Evans claims he was responsible for insisting on the three-hour version after Coppola trimmed the footage too short, leaving out so many of the memorable scenes the head of production had seen in the dailies. Coppola insists he always wanted a longer version, but he cut the picture short to accommodate the studio on Evans’ orders. But this is just one example of the many disagreements between the director and Evans, who also said he fired Coppola four times from the set. When things went wrong, they played the blame game. When things went right, Coppola and Evans both claimed the credit in one of Hollywood’s most vocal and lasting feuds, leaving history and self-promotion inseparable. Producer Frank Yablans, who oversaw the marketing and distribution of the film, offered his perspective in Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, saying that Evans “created a myth that he produced The Godfather. Evans did not save The Godfather. Evans did not make The Godfather. That is a total figment of his imagination.” These disputes and finger-pointing would continue for years, underlining how strange it is that The Godfather feels so intentional in every choice for most fans and critics.

Regardless of Coppola and Willis’ entrenched visual and thematic organization, everyone on the studio side was telling Coppola that what he was doing was wrong and terrible. Only the occasional outsider boosted Coppola’s confidence that his instincts had produced something incredible. For example, when Coppola asked screenwriter Robert Towne to help write a scene between Don Vito and Michael to set the stakes, he showed the famed Hollywood script doctor and later Oscar-winner for Chinatown (1974) some early footage. Towne—who wrote the only scene that finds Don Vito and Michael conferring about business and family, a strategic piece of plotting and character building—was floored and told Coppola it was “amazing.” As for the final cut, Coppola turned in a version that ran just over two hours, following Evans’ warning that the studio would take the picture out of Coppola’s hands if it ran longer. Evans claims he was responsible for insisting on the three-hour version after Coppola trimmed the footage too short, leaving out so many of the memorable scenes the head of production had seen in the dailies. Coppola insists he always wanted a longer version, but he cut the picture short to accommodate the studio on Evans’ orders. But this is just one example of the many disagreements between the director and Evans, who also said he fired Coppola four times from the set. When things went wrong, they played the blame game. When things went right, Coppola and Evans both claimed the credit in one of Hollywood’s most vocal and lasting feuds, leaving history and self-promotion inseparable. Producer Frank Yablans, who oversaw the marketing and distribution of the film, offered his perspective in Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, saying that Evans “created a myth that he produced The Godfather. Evans did not save The Godfather. Evans did not make The Godfather. That is a total figment of his imagination.” These disputes and finger-pointing would continue for years, underlining how strange it is that The Godfather feels so intentional in every choice for most fans and critics.

The film’s strategic slow release into theaters, compounded by exultant praise from nearly every prominent critic from Variety to Pauline Kael to Vincent Canby, resulted in a major box-office success for Paramount. The film opened in March and remained in theaters for much of 1972, earning upwards of $250 million worldwide. The Godfather was credited with not only saving the studio but saving the struggling film industry by reminding everyone that art and commerce could work in unison. David Lean, director of Lawrence of Arabia (1962), wrote Coppola and told him, “Your film is a real shot in the arm for anyone who loves our medium.” The rarity of The Godfather is that, even though Coppola was a director-for-hire at the outset, it became a blend of uncompromising artistry and commercial success. “A work of art that is also a blockbuster,” as Seal described it in his book. Kael wrote something similar: “If there was ever a great example of how the best popular movies come out as a merger of commerce and art, The Godfather it is.” The film’s triumph continued into 1973 on Oscar night. Nominated for ten Academy Awards, The Godfather did not win the most awards that night; Bob Fosse’s Cabaret won eight statues. But The Godfather won Oscars for Best Picture, Best Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium for Puzo and Coppola, and Best Actor for Brando. The accolades continued for years to come. In 1998, the American Film Institute ushered in the new millennium with a list of the 100 greatest films of all time. The Godfather came in third after Casablanca (1942) and the list’s highest-ranked Citizen Kane (1941). When they reordered the list in 2007, it moved up a spot ahead of Casablanca.

Beyond money and awards, the film turned out iconic performances and catapulted the careers of Pacino, Keaton, and many others; reignited Brando’s reputation; and turned Coppola into Paramount’s golden child for the remainder of the 1970s. They quickly signed the director to two sequels, gave him the freedom to make The Conversation before The Godfather Part II (both in 1974), and earned him enough clout to finance another passion project with United Artists, Apocalypse Now (1979). And The Godfather has sustained Coppola’s legend and career in the decades since. He continues to revisit the trilogy—a seemingly endless wellspring of financial opportunity with new restorations, home video releases, alternate cuts, and anniversaries. Sometimes, he seems compelled by his artistic desire; other times, he’s obligated by Paramount to revisit their enduring cash cow: the made-for-TV chronological cut, the 2018 “Coppola Restoration” consisting of a new audio and visual cleanup, and The Death of Michael Corleone in 2020 to give his underrated Part III another shot. In a stroke of irony, Coppola’s film decrying the dangers and corruptibility of capitalism has been his most enduring financial reservoir. And each time Coppola returns to it, The Godfather and its sequels create a renewed interest among moviegoers through this wide array of cuts and visual presentations. Upon the time of this essay, the film celebrates its 50th anniversary, prompting a new 4K restoration, theatrical rerelease, and physical media boxed set.

The film has also become a source of endless references, spoofs, and parodies. But none gets to the core of The Godfather better than You’ve Got Mail (1998), Nora Ephron’s remake of the Ernst Lubitsch comedy The Shop Around the Corner (1940). Ephron, who was married to Goodfellas (1990) and Casino (1995) author and screenwriter Nicholas Pileggi from 1987 until her death in 2012, had an affinity for gangster subjects despite her tendency to favor romantic comedies. Her screenplay of My Blue Heaven (1990) was a Steve Martin comedy based on the life of mobster and FBI informant Henry Hill, the same figure portrayed in Goodfellas. For You’ve Got Mail, Ephron not only quotes The Godfather at length, but her film follows a similar thematic trajectory. In the lighthearted rom-com, Tom Hanks’ corporate bookstore owner exchanges anonymous emails with Meg Ryan, a clerk at a small, privately owned bookshop he will soon put out of business. Not realizing he’s her competition, she asks for business advice, and he tells her to “Go to the mattresses.” He explains the line is from The Godfather, which he calls “the I Ching,” and explains further: “The Godfather is the sum of all wisdom. The Godfather is the answer to any question. What should I pack for my summer vacation? ‘Leave the gun, take the cannoli.’ What day of the week is it? ‘Maunday, Tuesday, Thursday, Wednesday.’ And the answer to your question is ‘Go to the mattresses.’” Besides using the film as a quotable source of wisdom, Ephron recognizes Coppola’s theme about capitalism crushing sentimental notions of family, mom-and-pop businesses, and Old World ties, represented by Ryan’s modest bookstore. Of course, Hanks and Ryan end up together in the film, but only after Hanks’ corporation puts Ryan’s shop out of business. You’ve Got Mail captures the same brutality of Michael’s underworld takeover—with all the charm Ephron, Hanks, and Ryan can muster, which is a lot—while also acknowledging The Godfather’s status in American culture as a mythic text and reference point.

The film has also become a source of endless references, spoofs, and parodies. But none gets to the core of The Godfather better than You’ve Got Mail (1998), Nora Ephron’s remake of the Ernst Lubitsch comedy The Shop Around the Corner (1940). Ephron, who was married to Goodfellas (1990) and Casino (1995) author and screenwriter Nicholas Pileggi from 1987 until her death in 2012, had an affinity for gangster subjects despite her tendency to favor romantic comedies. Her screenplay of My Blue Heaven (1990) was a Steve Martin comedy based on the life of mobster and FBI informant Henry Hill, the same figure portrayed in Goodfellas. For You’ve Got Mail, Ephron not only quotes The Godfather at length, but her film follows a similar thematic trajectory. In the lighthearted rom-com, Tom Hanks’ corporate bookstore owner exchanges anonymous emails with Meg Ryan, a clerk at a small, privately owned bookshop he will soon put out of business. Not realizing he’s her competition, she asks for business advice, and he tells her to “Go to the mattresses.” He explains the line is from The Godfather, which he calls “the I Ching,” and explains further: “The Godfather is the sum of all wisdom. The Godfather is the answer to any question. What should I pack for my summer vacation? ‘Leave the gun, take the cannoli.’ What day of the week is it? ‘Maunday, Tuesday, Thursday, Wednesday.’ And the answer to your question is ‘Go to the mattresses.’” Besides using the film as a quotable source of wisdom, Ephron recognizes Coppola’s theme about capitalism crushing sentimental notions of family, mom-and-pop businesses, and Old World ties, represented by Ryan’s modest bookstore. Of course, Hanks and Ryan end up together in the film, but only after Hanks’ corporation puts Ryan’s shop out of business. You’ve Got Mail captures the same brutality of Michael’s underworld takeover—with all the charm Ephron, Hanks, and Ryan can muster, which is a lot—while also acknowledging The Godfather’s status in American culture as a mythic text and reference point.

Moreover, The Godfather redefined the audience’s understanding of screen gangsters, established by classical Hollywood archetypes. Although the broad descriptions of organized crime explored by studios such as Warner Bros. in the ’30s and ’40s portrayed sensational violence with a moralizing message demanded by the Production Code, it’s easier to watch The Godfather and find the Corleone’s world appealing. Vito controls a small empire from his living room, and for people who feel powerless in their everyday lives, that’s a very attractive notion. Coppola admitted, “People love to read about an organization that’s really going to take care of us… When the courts fail you and the whole American system fails you, you can go to Don Corleone and get justice.” In his critical biography about Coppola, Peter Cowie notes that the Don’s “dignified” and “courtly behavior” tends to romanticize the character, ignoring the real-life violence and uncouth behavior of Mafia leaders recorded in court hearings. As with many subsequent gangster films, representation is often mistaken as a glamorization of the Mafia’s code of violence.

For a film about Michael destroying his family and straying from his father’s example to keep the business afloat, the idea that anyone could interpret the story as romantic remains curious. Perhaps the scenes detailing Vito’s backstory in Part II lend a romantic, rise-to-power narrative appeal. But the attractive prospect of the Corleone family’s self-empowerment, which is nonetheless marked by violence, ends with Vito. He sought to balance his family’s prosperity and his criminal enterprise. Viewers who argue that Part II is the superior film fail to recognize that the original says everything the story needed to say in this regard: The Corleones transform from a family into a business. The second film, albeit another landmark, reinforces the point through further narrative examples and a closer character study, building upon ideas conclusively established in its predecessor. One hesitates to call it redundant because, as it further illustrates that Michael has strayed from his father’s path, it deepens the myth of the Corleones. But there’s a quality about the original that feels singular, whereas the sequels feel innately secondary and tertiary. Indeed, along with the two sequels, countless other films about the Mafia followed The Godfather. But none, including Martin Scorsese’s brilliant inclusions in the genre—Goodfellas, Casino, The Irishman (2019)—boast the same classical themes and iconography that elevate Coppola’s film to the stuff of American myth.

The Godfather feels so essential to American cinema and mythology because it draws from established motifs in a grand tradition. If it feels ingrained into American storytelling, it might be because Puzo based his book on a Western, the only true American genre—1910’s The Heritage of the Desert, by Zane Grey. Readers and moviegoers had become accustomed to rooting for well-meaning outlaws and gunslingers who carved out a place for themselves in the Wild West. The gangster genre, Puzo recognized, was a variation on that theme. Puzo’s material deals in vast imagery and themes, from the baptism sequence that combines Christian motifs with murder and hostile takeover to Michael giving up his immortal soul to beat his competition. Coppola turns the story into an epic about universal generational conflicts that occur in a succession, when the former leader must give up their power for the next in line. Michael’s capitalist mindset and decidedly American way of doing business set aside his father’s Old World approach. Such imposing themes are bolstered by the lore surrounding its unlikely journey to the screen. The blended soup of conflicting accounts and behind-the-scenes drama, all of which has received as much coverage as the film itself, further engrains the film into the status of myth, inspiring a new tradition of storytelling about its production and legacy. Five decades later, The Godfather still resonates with the paradigm shifts from one generation to the next, still influences one filmmaker after another, and continues to be the foundation of a lasting mythology.

(Editor’s Note: This essay was commissioned on Patreon. Thank you for your generous support, Martha!)

Bibliography:

Biskind, Peter. Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-and-Rock ‘n’ Roll Generation Saved Hollywood. Simon and Schuster, 1998.

—. The Godfather Companion: Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About All Three Godfather Movies. Harper Perennial, 1990.

Coppola, Francis Ford. The Godfather Notebook. Regan Arts, 2016.

Cowie, Peter. The Godfather Book. Faber & Faber, 1997.

—. Coppola. André Deutsch, 2013.

—. The Godfather: The Official Motion Picture Archives, 2012.

Evans, Robert. The Kid Stays in the Picture: A Notorious Life. Hyperion Books, 1994.

The Godfather: The Coppola Restoration. Dir. Francis Ford Coppola. Paramount Pictures, 2008.

The Godfather Legacy. Dir. Kevin Burns. History Channel and Prometheus Entertainment, 2012.

Jones, Jenny M. The Annotated Godfather (50th Anniversary Edition): The Complete Screenplay, Commentary on Every Scene, Interviews, and Little-Known Facts. Black Dog & Leventhal, 2021.

Lebo, Harlan. The Godfather Legacy. Fireside, 1997.

Puzo, Mario. The Godfather. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1969.

Seal, Mark. Leave the Gun, Take the Cannoli: The Epic Story of the Making of The Godfather. Gallery Books, 2021.

Sragow, Michael. “Godfatherhood.” The New Yorker. 24 March 1997. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1997/03/24/godfatherhood. Accessed 10 January 2022.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review