The Definitives

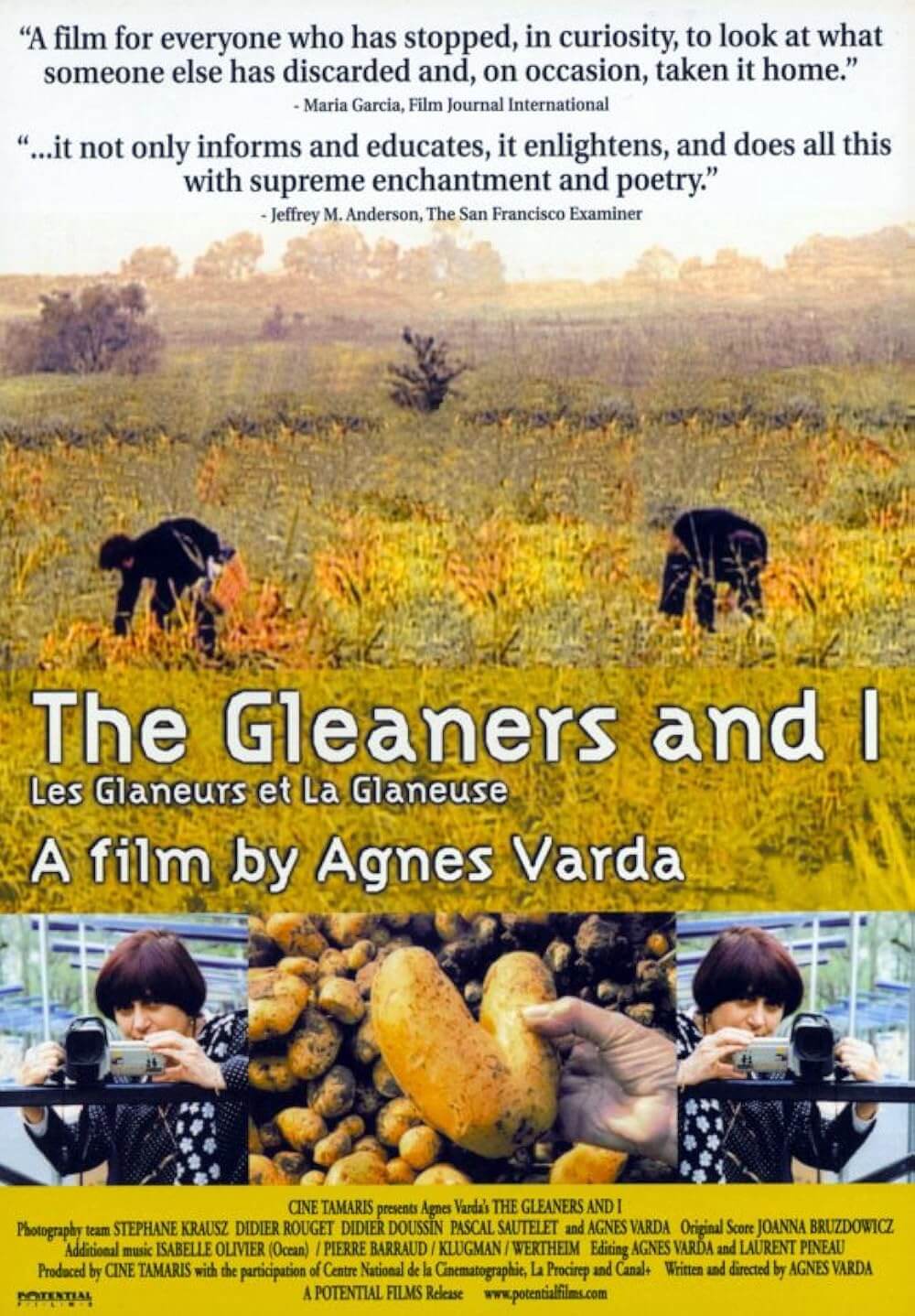

The Gleaners and I (2000)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

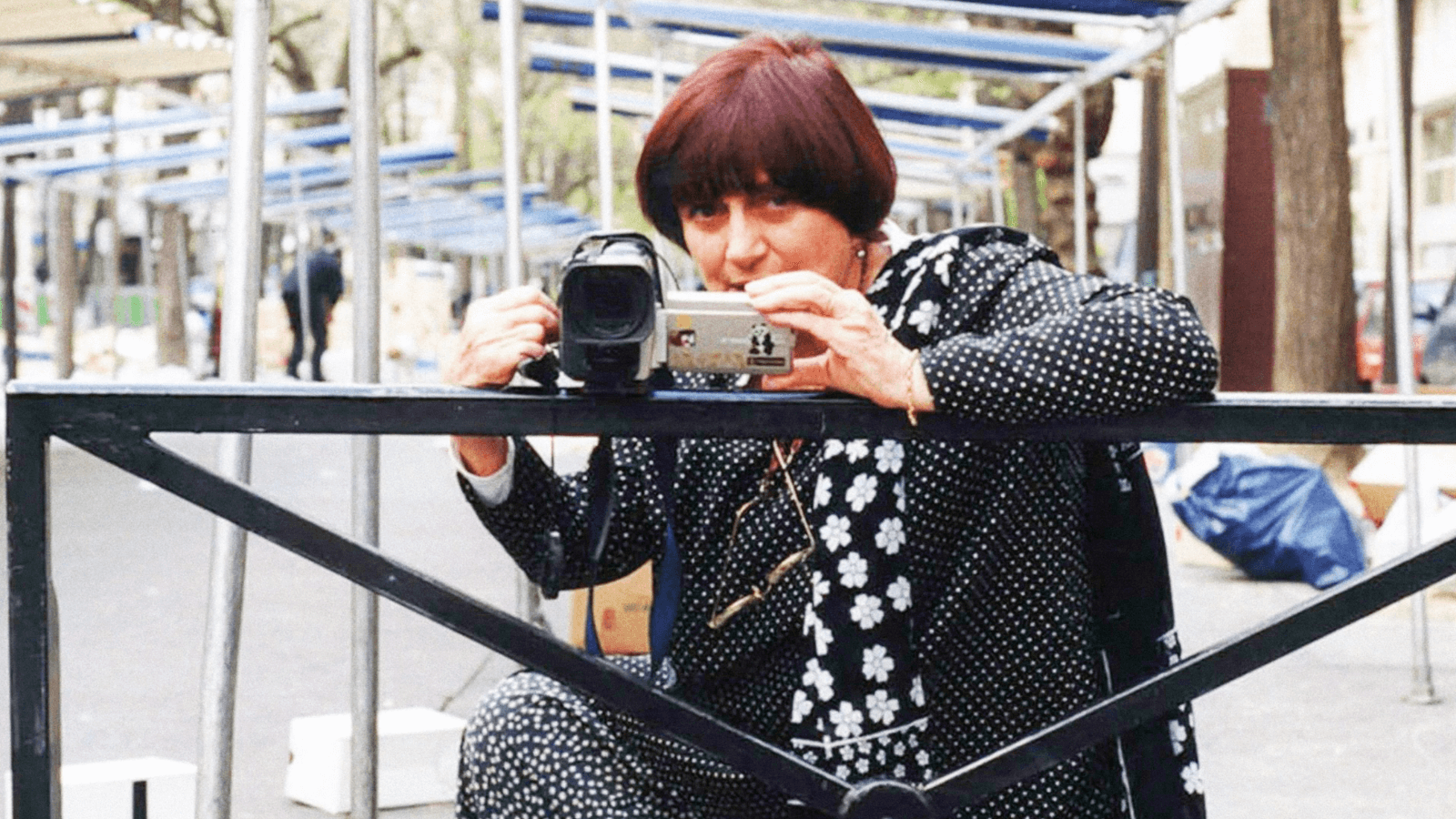

When I was a young boy, I would sit on my grandmother’s lap and examine her hands. Her skin looked transparent to me, thinly stretched over tendons and bones. My hands would follow the blue lines beneath her skin and note the faint liver spots. She would laugh when I poked her veins and moved them beneath her skin, and she told me that my skin would look like this when I became her age. She grew up on a farm in Minnesota, and she may have gleaned, though I never had a chance to ask her. I think about Irene’s hands while watching Agnès Varda’s The Gleaners and I, when the then 72-year-old filmmaker trains her digital camcorder on herself, “Filming one hand with the other,” she says. She considers how they’ve aged, and how, under the right conditions, they might serve as a framing device. Varda, who’s the grandmother every cinephile wishes they had, began her documentary as an investigation into the tradition of gleaning. She sought to explore people who take leftover food after the harvest because they must and those who make an ethical choice to glean to combat consumer waste. But rather than adopt an aesthetic pretense such as vérité style or direct cinema to capture her subject, Varda’s mode of filmmaking, like her best work, defies conventions and proves both experimental and personal. Equally as important to her subject, The Gleaners and I considers her own gleaning as a filmmaker, offering an unconventional self-portrait of someone who culls moments from the world and, through her unique perspective, turns them into art.

Historically, gleaners consisted of farm women who came along after the reapers, working in collectives to gather grain. Both secular law and religious decrees allow for gleaners—the destitute, hungry, and unemployed—to approach after the harvest, without worry of a trespassing charge. Varda’s film explores how the tradition of gleaning has changed; it now includes men, and these individuals often glean alone. While The Gleaners and I at first charts those who scavenge and salvage in France, both on the countryside and city streets, it also remarks on post-industrial agricultural downfalls. A self-described “road documentary” that finds Varda discovering people and objects as she goes, her film follows a random path that’s full of chance encounters. Varda meets hoboes, peasants, fruit growers, and other, more surprising subjects. In a field, she talks to an alcoholic who lost his trucking job, then his wife and three children, and now he lives in a makeshift trailer park. One impassioned young man in rubber boots has a job and studied economics at university, but he eats only out of garbage cans as an ethical imperative. Another man picks up the leftovers from a marketplace; Varda speaks to him and learns that he has a Master’s degree, and he gives language lessons to immigrants for free in a subbasement. She receives her interviewees with grace, never judging or condescending to their situations, however bleak they may sometimes seem.

The impetus of Varda’s documentary came first from noticing the humility of the gleaning gesture in marketplaces. She notes in the film how people “humbly stoop down” and show reverence for Nature, and this motion drew her attention. She has empathy for people who cannot afford to buy without bending, what in France they call, “le geste auguste de semeur (the majestic gesture of the sower).” The gleaner will “pick up what’s left so nothing’s wasted.” And in the post-industrial world, machines leave much behind, just as society leaves certain groups of people behind. Varda acknowledges as much in the film’s onscreen French title, which indirectly includes her in the bunch: Les Glaneurs (the gleaners)—though, it’s sometimes credited as Les Glaneurs et la Glaneuse, a title meaning The Gleaners and the Gleaner. The longer French title doesn’t translate well due to the French language’s gendered nouns. The shorter, original title is a simpler and more evocative label that resists overexplaining Varda’s crucial subjective perspective as the English-language title does (think Michael Moore’s Roger & Me, 1989). After all, the film is less about Varda’s relationship with gleaners than her inclusion among them as a documentary filmmaker, extracting images from her everyday experience with her handheld digital camera.

The impetus of Varda’s documentary came first from noticing the humility of the gleaning gesture in marketplaces. She notes in the film how people “humbly stoop down” and show reverence for Nature, and this motion drew her attention. She has empathy for people who cannot afford to buy without bending, what in France they call, “le geste auguste de semeur (the majestic gesture of the sower).” The gleaner will “pick up what’s left so nothing’s wasted.” And in the post-industrial world, machines leave much behind, just as society leaves certain groups of people behind. Varda acknowledges as much in the film’s onscreen French title, which indirectly includes her in the bunch: Les Glaneurs (the gleaners)—though, it’s sometimes credited as Les Glaneurs et la Glaneuse, a title meaning The Gleaners and the Gleaner. The longer French title doesn’t translate well due to the French language’s gendered nouns. The shorter, original title is a simpler and more evocative label that resists overexplaining Varda’s crucial subjective perspective as the English-language title does (think Michael Moore’s Roger & Me, 1989). After all, the film is less about Varda’s relationship with gleaners than her inclusion among them as a documentary filmmaker, extracting images from her everyday experience with her handheld digital camera.

When Varda discovered the ease of using a digital camera, specifically the Sony DVR CAM DSR 300, she decided to use it on this project to facilitate what she called “artistic gleaning” from her subjects. Varda told Melissa Anderson, “I had the feeling that this is the camera that would bring me back to the early short films I made in 1957 and 1958. I felt free at that time. With the new digital camera, I felt I could film myself, get involved as a filmmaker.” Without an obtrusive camera setup, she found her interviewees were more willing to engage with her, while she could more easily feel part of the moment her camera captured. The digital camera gives way to an intimacy in Varda’s approach, reflected in the first shot’s handcrafted and personal quality: Varda’s cat rests atop her computer, the monitor flickering the film’s title, as though adding the title in post-production would have been too impersonal (regardless, a post-production title does appear onscreen). Sometimes shooting alone, sometimes accompanied by her assistants, Varda creates art by recording and assembling the footage through her artistic lens. Her approach to documentary finds a parallel in her encounters with found object artists and collage makers, among them a former bricklayer who assembles vast totem towers of discarded dolls. Is this art? “Perhaps,” the man’s wife concedes, adding an amusing critique of her spouse: “There’s much better around.”

Varda’s interest in the subject is not without precedent in her career. In her fifteen features and many more shorts by 2001, she had already demonstrated an interest in outsiders who have been cast aside and forgotten by conventional society. She shot Black Panthers in the summer of 1968, humanizing a group that operated on the fringes of society for freedom and equality, though they were deemed radicals by their government. In her 1969 portrait of Los Angeles counter culture, Lions of Love, Varda centered her camera on a free-loving threesome who experience the world passively and critically. In Vagabond (1985), Sandrine Bonnaire plays a young woman who rejects kindness and conformity in whatever its form; her defiantly independent journey takes her against the grain, always moving right to left, opposite of the usual left-to-right path of progression. So it makes sense that, armed with a handheld digital camera, Varda would be drawn to real-life characters on the margins of French society. Not only that, but also a wealth of fruits, vegetables, and discarded objects, along with her forgotten people.

Functioning as a portrait of gleaners, the film reveals staggering agricultural waste. Varda learns that 25 tons of potatoes get thrown away because supermarkets prefer potatoes of a particular size. The many people who might eat these potatoes don’t know where the unwanted potatoes are dumped, so the produce turns green and inedible. Others flock to these spots, taking hundreds of pounds of potatoes away in large sacks. An apple farmer estimates that 10 tons of his product goes to waste. Elsewhere, a vineyard enforces quota limits on its crop yield, leaving many of its grapes unpicked and rotting on the vine. Those who refuse to allow gleaning aren’t “being nice,” according to Varda, who consults an attorney armed with a law that grants the poor or destitute permission to glean. Still, when there are so many homeless and hungry, how can this be the solution? How can there not be an official system designed to glean to feed those in need? The grocery stores themselves throw away food to keep turning over their inventory. But François, the impassioned man in the rubber boots, ignores expiration dates and goes by smell. Restaurants waste food too, but one interviewee, a chef and “born picker,” uses everything to avoid excess and save on costs. In another segment, Varda praises the Musée en Herbe’s school program that teaches children about sustainability and how to find value in trash by making found art, and her central theme about the value of what we think of as waste is thoughtfully underlined.

Functioning as a portrait of gleaners, the film reveals staggering agricultural waste. Varda learns that 25 tons of potatoes get thrown away because supermarkets prefer potatoes of a particular size. The many people who might eat these potatoes don’t know where the unwanted potatoes are dumped, so the produce turns green and inedible. Others flock to these spots, taking hundreds of pounds of potatoes away in large sacks. An apple farmer estimates that 10 tons of his product goes to waste. Elsewhere, a vineyard enforces quota limits on its crop yield, leaving many of its grapes unpicked and rotting on the vine. Those who refuse to allow gleaning aren’t “being nice,” according to Varda, who consults an attorney armed with a law that grants the poor or destitute permission to glean. Still, when there are so many homeless and hungry, how can this be the solution? How can there not be an official system designed to glean to feed those in need? The grocery stores themselves throw away food to keep turning over their inventory. But François, the impassioned man in the rubber boots, ignores expiration dates and goes by smell. Restaurants waste food too, but one interviewee, a chef and “born picker,” uses everything to avoid excess and save on costs. In another segment, Varda praises the Musée en Herbe’s school program that teaches children about sustainability and how to find value in trash by making found art, and her central theme about the value of what we think of as waste is thoughtfully underlined.

Besides speaking to actual gleaners, Varda also demonstrates an interest in representations of gleaning. At several points in the film, she references paintings of gleaners. She notes that Jean-François Millet’s The Gleaners, an oil painting from 1857 hanging in the Musée d’Orsay, is reproduced in the dictionary next to the entry for glaneuses (the plural of gleaners). Early in the film, she poses next to another image, The Gleaner, from 1877, by French realist Jules Breton, which hangs in the Musée des Beaux Arts in Arras. In the painting, a woman stands almost powerfully with a bushel of wheat on her shoulder. Varda replicates the image in the museum, standing before drapery and posing like the figure in Breton’s painting. She lets the ears of wheat drop from her shoulder, and in a single motion, the hand that was resting on her hip rises to reveal her digital camcorder. “Included in the gleaners in the title of this film,” she says, “is me.” In this moment, she declares herself both a gleaner and an artist—she is the subject and the observer.

Documentary filmmaking is a process whereby the filmmaker determines what is important while shooting and, from that, applies their artistic subjectivity. Although she spends much of her 82-minute film with her camera on various gleaners, Varda herself is a constant presence either in her voiceover or her appearance onscreen. Although Varda often refers to herself as “I” in the film, scholar Virginia Bonner argues that she is “filming in the second person,” an argument that represents a kind of aesthetic mathematical division between the objective third-person style and the fully subjective on-camera, first-person style of documentary that, say, Michael Moore might produce. Indeed, Varda often speaks directly to the audience, using “you” instead of “I” when she says things like, “You don’t look at them,” referring to scavengers in the streets. However, she often refers to herself in the first person, and despite my remarks about the title above, the film is most commonly known by its English-language title. What makes The Gleaners and I more than a documentary about an important social problem is its self-reflexivity by a filmmaker unafraid to include herself in the story—now a fairly commonplace occurrence in documentaries.

The most compelling aspect of the film is Varda’s perspective, and how she draws connections between her aging body and the decaying, unharvested food. Just as sustenance remains in recently expired food and unculled produce, there’s artistic life in the old lady yet. Varda seems fully aware that her expiration date is approaching (she died in 2019). While looking at her wrinkled hands and graying hair, she remarks, “My hair and my hands tell me the end is near.” But rather than approach age with trepidation, she finds an aesthetic beauty in how she has changed—a perspective that applies to many of the discarded people and food items she encounters. Still, she is not without her anxieties about getting older. From a collection of trash on a street, she rescues a clock without hands and notes that it is “My kind of thing” because “you don’t see time passing.” Varda sees time as a social construction with potentially damaging ramifications, whether it’s assigning food an expiration date too soon or writing off septuagenarians who can still be useful.

The most compelling aspect of the film is Varda’s perspective, and how she draws connections between her aging body and the decaying, unharvested food. Just as sustenance remains in recently expired food and unculled produce, there’s artistic life in the old lady yet. Varda seems fully aware that her expiration date is approaching (she died in 2019). While looking at her wrinkled hands and graying hair, she remarks, “My hair and my hands tell me the end is near.” But rather than approach age with trepidation, she finds an aesthetic beauty in how she has changed—a perspective that applies to many of the discarded people and food items she encounters. Still, she is not without her anxieties about getting older. From a collection of trash on a street, she rescues a clock without hands and notes that it is “My kind of thing” because “you don’t see time passing.” Varda sees time as a social construction with potentially damaging ramifications, whether it’s assigning food an expiration date too soon or writing off septuagenarians who can still be useful.

Time nags at Varda, just like her titular character from Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962), but both Varda and Cléo emerge with an unlikely optimism. Varda’s interest in time is an acknowledgment that she has time left, that she is useful, despite how society discards senior citizens. So it’s telling when, while looking at a pile of rejected potatoes, she urgently reaches for one that looks like two mutant children spliced together. Regardless of how shoppers might overlook such a potato in the produce aisle for its unconventional appearance, Varda doesn’t see it as misshapen; she describes it as heart-shaped and takes it home. Over time, the potato begins to rot, and she compares it to the Rembrandt self-portrait postcards she acquired in Tokyo. Rembrandt was known for his visual exploration of body types that did not conform to the typical standards of beauty at the time. He depicted nude, aged women in inks, and he painted self-portraits into old age until he could no longer see clearly. His later self-portraits may not feature the pristine detail of his younger work, but there’s no doubting the vital energy he captures in his eyes. Varda’s film addresses how society values the marketable traits of youth and beauty, but she questions these capitalistic motivations and finds virtue in the alternative: the aged and unsightly, but not unuseful. She sees her moldy ceiling as an abstract work of art; she meets people who find edible food among trash; she picks fruit from a tree that has just been harvested; she reconsiders the entire notion of “misshapen” in regard to a potato.

The Gleaners and I would not be the film it is without Varda’s way of framing and looking at the world. On the road, she plays a game with the semi-trucks her vehicle passes on the highway. She holds her hand close to the camera in a C-shaped formation, pretending to grab each truck as they pass (doubtless, Varda would enjoy Kevin McKinney’s “I’m crushing your head” character from The Kids in the Hall). To be sure, her perspective also gives way to humor and peculiarity. Toward the end of her film, she embraces a certain randomness in her observations. Cutting to various lion statues in Paris, she notes, “My neighbor the Lion of Denfert is made of bronze” and “My friend the Lion of Arles is made of stone.” Or she stops to notice a man watching the river flow. Such moments say nothing of her film’s thematic or aesthetic agenda, but they mark her work as that of a singular voice, unmistakably so. Even years after Varda’s death, her late image remains impossible to forget—that of a mischievous artist working on the margins. She appears with a wry smile and distinct hair, gray on top and dyed red on the bottom. She had up-to-something eyes and a playful outlook about her. She seemed casual but also insightful, a quality apparent in her documentaries.

The Gleaners and I was one of many self-assessing films that Varda made in the last few decades of her career, each concerning memory and reflection in cinematic terms. She admits in interviews from the time that she had begun to struggle with memory, so she sought to document her remembrances. The first of these projects came after the death of her filmmaker husband, Jacques Demy, whom she married in 1962 and remained with until his passing in 1990. A year later, she released Jacquot de Nantes (1991), a drama about Demy’s early life, followed by its documentary equivalent in 1995, The World of Jacques Demy, which showcases Demy’s early life and career. Given that their careers had progressed so closely, she also memorialized Demy’s work with The Young Girls Turn 25 (1993), which looks back at one of her husband’s masterpieces, The Young Girls of Rochefort (1967). Not all of her reflective filmmaking was autobiographical. With One Hundred and One Nights (1994), she made a kind of dramatized documentary celebrating the first hundred years of cinema, where Simon Cinema, played by Varda’s longtime collaborator Michel Piccoli, reflects on film history, allowing Varda to present her version in a hardly all-inclusive portrait of cinema. In the years to follow, her documentaries would become ever more self-centric with The Beaches of Agnès (2008) and Varda by Agnès (2019).

The Gleaners and I was one of many self-assessing films that Varda made in the last few decades of her career, each concerning memory and reflection in cinematic terms. She admits in interviews from the time that she had begun to struggle with memory, so she sought to document her remembrances. The first of these projects came after the death of her filmmaker husband, Jacques Demy, whom she married in 1962 and remained with until his passing in 1990. A year later, she released Jacquot de Nantes (1991), a drama about Demy’s early life, followed by its documentary equivalent in 1995, The World of Jacques Demy, which showcases Demy’s early life and career. Given that their careers had progressed so closely, she also memorialized Demy’s work with The Young Girls Turn 25 (1993), which looks back at one of her husband’s masterpieces, The Young Girls of Rochefort (1967). Not all of her reflective filmmaking was autobiographical. With One Hundred and One Nights (1994), she made a kind of dramatized documentary celebrating the first hundred years of cinema, where Simon Cinema, played by Varda’s longtime collaborator Michel Piccoli, reflects on film history, allowing Varda to present her version in a hardly all-inclusive portrait of cinema. In the years to follow, her documentaries would become ever more self-centric with The Beaches of Agnès (2008) and Varda by Agnès (2019).

Much like her dramatic output, Varda’s documentaries prove difficult to classify within conventional definitions, and that makes them appealing. Similar to Cléo from 5 to 7, which segments real-time sequences into short episodes of her protagonist’s perspective, The Gleaners and I contains subjective and objective levels. She acknowledges that a documentary is “real,” consisting of captured moments from reality with non-actors. However, she also acknowledges how a documentary filmmaker creates a story through editing and music. She told Anderson, “I really work as a filmmaker, I would say, to give a specific shape to that subject.” And yet, despite the examples above, Varda has always had a role in her documentaries, no matter how peripheral. When she made Daguerréotypes (1975)—about the assortment of people in the community where she lived since the 1950s—she narrated and caught herself in a reflection. Varda’s closest comparison might be Werner Herzog, who’s more interested in the poetic potential of images than their objectivity. Varda said, “The objective is the facts, society’s facts, and the subjective is how I feel about that, or how I can make it funny or sad or poignant. Making a film like this is a way of living. It’s not just a product. It has been organized and finished and delivered.”

Varda had low expectations when she made The Gleaners and I, thinking it would never reach a wide audience. The film debuted out of competition at the Cannes Film Festival in 2000, where it received widespread praise. An extended run in French theaters and the global festival circuit followed, along with many awards, including the Méliès Prize for Best French Film of 2000 from the French Union of Film Critics—a rare prize for a documentary feature. The film has since earned its place on Sight and Sound’s critics’ poll of the 100 greatest films of all time. Varda’s work proved so popular that she couldn’t resist making a sequel in 2002, called The Gleaners and I: Two Years Later (Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse… deux ans après). In it, she reconnects with several popular interview subjects from the original, while also remarking on the unlikely praise and dozens of awards she received after its release. In the sequel, a woman named Delphine remarks how the film was a “rebirth” for her, changing how she lives her life. Varda questions this, noting that the film talks about “abandoned” objects. Delphine agrees but adds, “But it’s made by someone who is very much alive.”

The Gleaners and I is about a way of thinking—not only about products and the food industry as a whole, but about the world. Critic Harlan Jacobson writes, “The world of the gleaner is a completely personified world, where every object is the lost expression of some mother’s intention and so must be rescued.” Varda’s moving philosophy sees life in discarded objects; what is more, she refuses to define her life according to what society deems worthwhile. She knows she has more use than that, and so she doesn’t mourn getting older. Instead, she finds new forms of beauty in her wrinkled hands, heart-shaped potatoes, and the flavors of tossed-aside food. Just as society has deemed expired and discarded produce something less-than, it looks down on gray hair and wrinkles. If Varda had wanted to, she could have further underscored how society rarely takes care of its elderly citizens, often shuffling them off to care centers, where they’re ignored or abused by the staff or exploited by legal guardians. Near the end, my grandmother was put into one of these places. I dreaded visiting her there as a teenager because the conditions were awful. Varda refuses to be seen as many people that age are, like food tossed one day after the expiration date.

The Gleaners and I is about a way of thinking—not only about products and the food industry as a whole, but about the world. Critic Harlan Jacobson writes, “The world of the gleaner is a completely personified world, where every object is the lost expression of some mother’s intention and so must be rescued.” Varda’s moving philosophy sees life in discarded objects; what is more, she refuses to define her life according to what society deems worthwhile. She knows she has more use than that, and so she doesn’t mourn getting older. Instead, she finds new forms of beauty in her wrinkled hands, heart-shaped potatoes, and the flavors of tossed-aside food. Just as society has deemed expired and discarded produce something less-than, it looks down on gray hair and wrinkles. If Varda had wanted to, she could have further underscored how society rarely takes care of its elderly citizens, often shuffling them off to care centers, where they’re ignored or abused by the staff or exploited by legal guardians. Near the end, my grandmother was put into one of these places. I dreaded visiting her there as a teenager because the conditions were awful. Varda refuses to be seen as many people that age are, like food tossed one day after the expiration date.

Varda’s perspective recalls how one character chooses to view a small farming town map, which indicates dumping grounds for various produce overages. Intended as a map of refuse, Varda and the gleaner recognize its function as a map for food. In a similar way, The Gleaners and I offers an alternate method of understanding the world by having an open conversation between the director, the subjects of her film, and the viewer. She draws connections between her subjects and herself—decidedly distinct groups in social situations that couldn’t be more different. As spectators, we cannot help but see ourselves in Varda and the people she interviews; we cannot help but want to change our lives. Though, Varda never takes an activist approach or offers a call to action. She inspires us in the most unlikely ways. In one memorable scene, she looks back at her footage and finds that she forgot to shut off her camera. With the camera pointed toward the ground, she captures her lens cap doing a “crazy jig,” which she amusingly sets to fervent jazz. Even in her errors as a filmmaker, there is something oddly fascinating, funny, witty, and insightful about her footage. Another documentarian would discard the digital footage in the trash bin. Varda turns the footage into a metaphor for her entire film. That’s her magic.

(Note: This essay was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on July 19, 2023. )

Bibliography:

Anderson, Melissa, and Agnès Varda. “The Modest Gesture of the Filmmaker: An Interview with Agnès Varda.” Cinéaste, vol. 26, no. 4, 2001, pp. 24–27. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41689394. Accessed 4 July 2023.

Conway, Kelley. Agnes Varda. Contemporary Film Directors. University of Illinois Press, 2015.

DeRoo, Rebecca J. Agnes Varda between Film, Photography, and Art. University of California Press, 2018.

Ince, Kate. “Feminist Phenomenology and the Film World of Agnès Varda.” Hypatia, vol. 28, no. 3, 2013, pp. 602–17. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24542005. Accessed 4 July 2023.

Jacobson, Harlan. “Review: The Gleaners and I.” Film Comment, vol. 37, no. 2, 2001, pp. 76–76. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43578429. Accessed 28 June 2023.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review