The Definitives

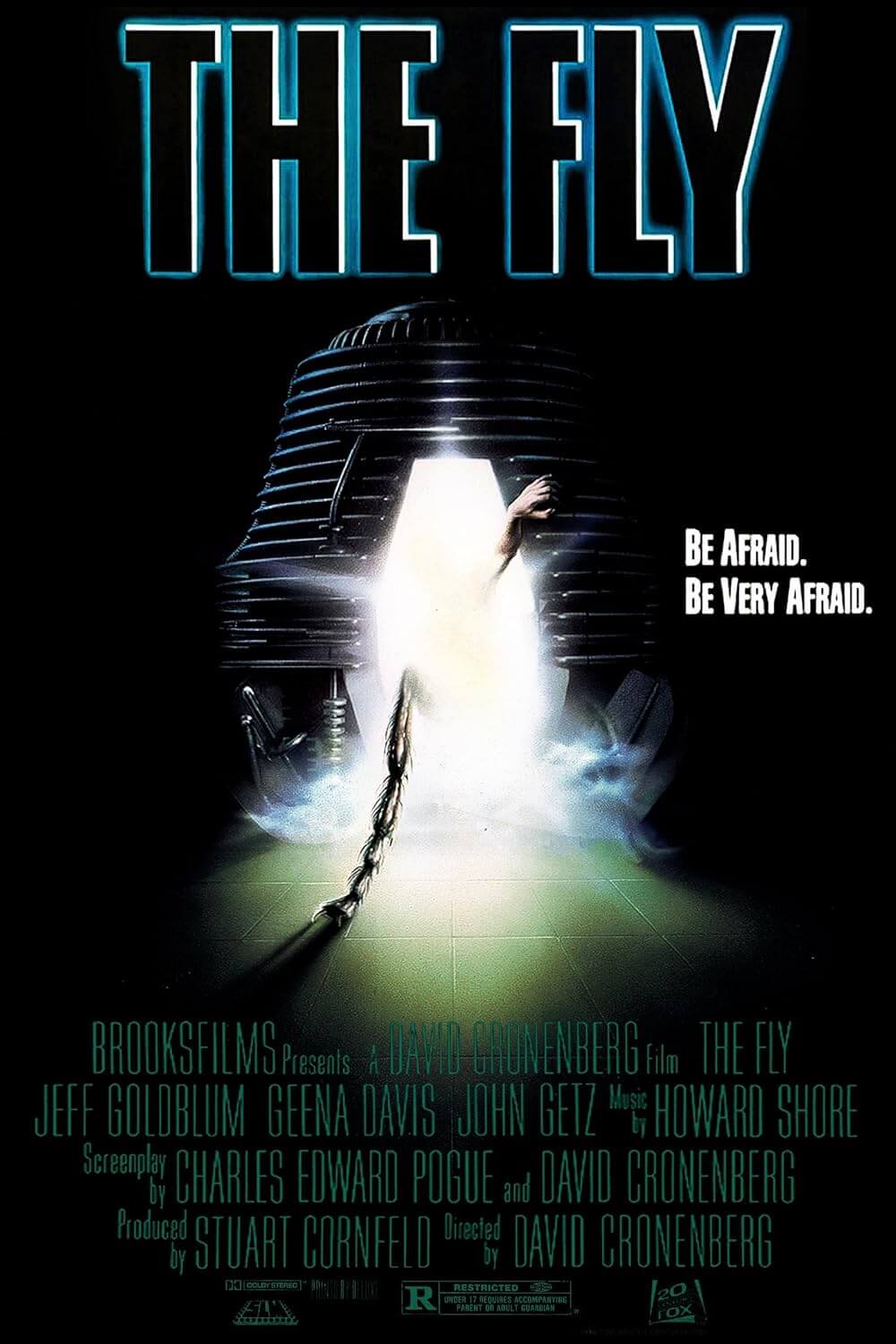

The Fly (1986)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

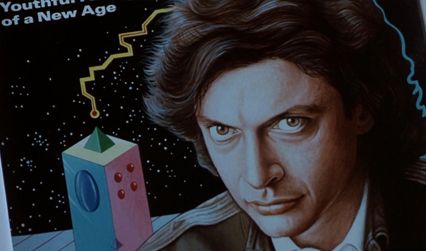

Mind and body cannot coexist. Each works according to its own set parameters, degenerating with time, never in unison. Oblivious to the body, the mind exists freely until it is forced to contemplate its carrier. We take our bodies for granted pending disease or injury damaging them, at which point our minds are helpless to do anything but allow the body to run its course. We look in the mirror and suddenly we are not that person we once recognized. We get old, thin, wrinkled, or fat, our hair changes color, or any number of aging signs. Somehow we feel different from what we see; our bodies have betrayed us. This mind-body dichotomy suggests that biology is, to some extent, inconsequential next to human consciousness—that consciousness exists without benefit of bodily interference. The cinema of Canadian filmmaker David Cronenberg infers an alternate theme: human corporeality exists parallel to, if not wholly exceeding, cognitive substance. Cronenberg’s 1986 film The Fly delivers an introspective conflict between the genius mind of Seth Brundle, played in a virtuoso performance by Jeff Goldblum, and the character’s body.

Brundle is a withdrawn scientist eager for human interaction. He finds himself a lover in journalist Veronica Quaife (Goldblum’s real-life girlfriend at the time, Geena Davis), who covers the development of his new invention. Secretly working in his loft under the radar of the science community, Brundle has created Telepods—conduits through which he can transport objects from one place to another. He discovers from an incident with an inside-out baboon that his computer can only understand inanimate objects. Something about flesh confuses his technology, possibly because his own body is disregarded in place of brain power, and thus he projects his bodily apathy onto the computer. He explains in one scene that he suffers from motion sickness; physical movement makes him nauseous, hence the Telepods. But much of his life is organized around embracing the mind and dismissing the body; for instance, his wardrobe consists of multiple copies of the shame shirt, sportcoat, and shoes, so like Einstein before him, Brundle will have to expend as little mental energy as possible deciding what to wear.

Disguised as a mad scientist horror movie, Cronenberg’s film is actually a tragic love triangle between Brundle, Veronica, and Stathis Borans, Veronica’s editor and ex-lover played by John Getz. A love affair develops between the isolated and vulnerable Brundle and his experienced lover Veronica. She covers his progress on the Telepods, while he experiences the joys of her flesh, awakening him to the complications and mysteriousness inherent to the body. After making love, Brundle finds Veronica has opened his eyes to the body, inspiring him to reconfigure his computer with his newfound knowledge of organic importance. A test run with another baboon proves his Telepods are now potentially human-ready. Upon celebration, Brundle discovers Stathis is still a part of Veronica’s life; assuming the worst, he becomes jealous and drunk, and he teleports himself. When he does this, he has no idea that a fly de-moleculized with him, or that the computer has fused it with him on a molecular-genetic level upon rematerialization.

Disguised as a mad scientist horror movie, Cronenberg’s film is actually a tragic love triangle between Brundle, Veronica, and Stathis Borans, Veronica’s editor and ex-lover played by John Getz. A love affair develops between the isolated and vulnerable Brundle and his experienced lover Veronica. She covers his progress on the Telepods, while he experiences the joys of her flesh, awakening him to the complications and mysteriousness inherent to the body. After making love, Brundle finds Veronica has opened his eyes to the body, inspiring him to reconfigure his computer with his newfound knowledge of organic importance. A test run with another baboon proves his Telepods are now potentially human-ready. Upon celebration, Brundle discovers Stathis is still a part of Veronica’s life; assuming the worst, he becomes jealous and drunk, and he teleports himself. When he does this, he has no idea that a fly de-moleculized with him, or that the computer has fused it with him on a molecular-genetic level upon rematerialization.

Remaking the 1958 Kurt Neumann movie starring Vincent Price, Cronenberg worked from a script by Charles Edward Pogue, infusing his own brand of bodily reality into the material. The earlier version featured actor Al Hedison running about with a gigantic fly head; meanwhile, a tiny fly with an equally small human head found itself caught in a spider web—both are unable to communicate or draw any sympathy from the viewer. Cronenberg sees insect-human splicing as a progressive malady versus an instant change, one he compares to a disease, like a prolonged battle between the mind and body. When Cronenberg’s scientist first emerges naked from the smoking Telepod, he has no idea of the nightmarish disease-growth that awaits him. The Telepod translates Brundle and the absorbed fly into an enhanced physical product, euphoric and cleansed of bodily hindrances. Brundle explains that teleportation must have been a purification process… “Like a drug, a perfectly pure and benign drug.” His muscles are toned and glistening. Sex and gymnastics take over where intellectual prowess was formerly dominant. Brundle becomes a man of the flesh, constantly feeding on candy bars and ice cream, unendingly craving intercourse and other physical pursuits. In a café scene, Brundle rants that his work, his Intellectual Self has long been his focus; the Telepod has allowed for a Revolution of the Body, allowing him to find his “Real” Self.

Brundle’s revolution comes about in profound, horrifying extremes as Cronenberg transforms Brundle into Brundlefly. Goldblum underwent rigorous makeup treatment each morning before shooting, helping to show the character’s gradual decline in a series of episodic transitions. The process is a plodding, disgusting course filled with goopy special effects and impressive makeup work by Chris Walas Inc., exaggerating aspects of day-to-day human biology we might prefer to ignore. Brundle’s ignorance of the body prior to his affair suggests that we have forgotten about our own abjections: production of vomit, bile, excrement, gas, sweat, ejaculate, and the like—processes we attempt to conceal for fear of social rejection. Afterward, as his metamorphosis occurs, Brundle has no choice but to acknowledge his slimy orifices, pus-filled fingertips, and crumbling facial features, particularly when his body begins to fall apart. He even uses his medicine cabinet as a pseudo-Cabinet of Curiosities, what he calls “The Seth Brundle Museum of Natural History.” Though he was once ignorant of the body, his transmutation into a fleshy insect has forced him to acknowledge it, just as we might if suffering from a disease—only when there is something wrong with our bodies do we take notice of them. Brundle finally respects flesh, the mutual mind-body dependency he once took for granted.

Brundle’s revolution comes about in profound, horrifying extremes as Cronenberg transforms Brundle into Brundlefly. Goldblum underwent rigorous makeup treatment each morning before shooting, helping to show the character’s gradual decline in a series of episodic transitions. The process is a plodding, disgusting course filled with goopy special effects and impressive makeup work by Chris Walas Inc., exaggerating aspects of day-to-day human biology we might prefer to ignore. Brundle’s ignorance of the body prior to his affair suggests that we have forgotten about our own abjections: production of vomit, bile, excrement, gas, sweat, ejaculate, and the like—processes we attempt to conceal for fear of social rejection. Afterward, as his metamorphosis occurs, Brundle has no choice but to acknowledge his slimy orifices, pus-filled fingertips, and crumbling facial features, particularly when his body begins to fall apart. He even uses his medicine cabinet as a pseudo-Cabinet of Curiosities, what he calls “The Seth Brundle Museum of Natural History.” Though he was once ignorant of the body, his transmutation into a fleshy insect has forced him to acknowledge it, just as we might if suffering from a disease—only when there is something wrong with our bodies do we take notice of them. Brundle finally respects flesh, the mutual mind-body dependency he once took for granted.

Upon The Fly’s initial release, attention to AIDS fueled a panicky media storm, and so critics deemed the picture a metaphor for sexually transmitted diseases. Such an idea could not be less accurate when compared to Cronenberg’s natural biological intent, which suggests that the body disintegrates without the benefit of a disease, if given time. Age, in a way, is a disease that continuously attacks our bodies, and for which there is no cure. Age is a more apparent and consistent force than any disease could ever be. Failure of the human body generally occurs from “natural causes” much earlier than the mind, leaving the human psyche doomed inside a crumbling vessel. Brundle, at first, describes his mutation as a “bizarre form of cancer”; he later believes his mutation is instead a progression, that he is becoming something, as opposed to decaying from something.Externally, little remains of Brundle’s humanity; he is more insect than human. “Vomit-drop” liquefies his food, which is then sucked up and ingested; he walks on walls as if it was second nature. He warns Veronica, “Have you ever heard of Insect Politics? Neither have I. Insects don’t have politics. They’re very… brutal. No compassion. No compromise. We can’t trust the insect.”

As Brundlefly’s body takes over, he physically exists as more insect than human; he warns Veronica away as his mind is losing the battle to his burgeoning insect anatomy. Insects are instinctual creatures, driven to sustain their bodies. And Brundle’s body teems with insect impulse, a conflict he cannot help but lose. His body revolts against the mind, suggesting the body can exist without it. Philosophers like René Descartes would have you believe that in a body, which can be crippled by an accident or stricken with disease, the mind may flourish despite physical obstacles—that tissue is mind-independent, but not vice versa; that we can, and often are, betrayed by our bodies; that the mind is less apt to fail. Perhaps this is why there are more hospitals than lunatic asylums. And yet Descartes overlooks our sometimes superficial attachments to the body, how our attitudes and personalities change if we feel hungry, tired, or sick. Our bodies wear us down, directly influencing our state of mind. And even though our psyche struggles for independence in the mind-body dichotomy, achieving it is impossible, since biology and consciousness are directly related. We are condemned to physical processes, as grotesque as they may be.

As Brundlefly’s body takes over, he physically exists as more insect than human; he warns Veronica away as his mind is losing the battle to his burgeoning insect anatomy. Insects are instinctual creatures, driven to sustain their bodies. And Brundle’s body teems with insect impulse, a conflict he cannot help but lose. His body revolts against the mind, suggesting the body can exist without it. Philosophers like René Descartes would have you believe that in a body, which can be crippled by an accident or stricken with disease, the mind may flourish despite physical obstacles—that tissue is mind-independent, but not vice versa; that we can, and often are, betrayed by our bodies; that the mind is less apt to fail. Perhaps this is why there are more hospitals than lunatic asylums. And yet Descartes overlooks our sometimes superficial attachments to the body, how our attitudes and personalities change if we feel hungry, tired, or sick. Our bodies wear us down, directly influencing our state of mind. And even though our psyche struggles for independence in the mind-body dichotomy, achieving it is impossible, since biology and consciousness are directly related. We are condemned to physical processes, as grotesque as they may be.

Cronenberg, who is often called the “King of Venereal Horror”, provides one possible triumph of mind-over-body within The Fly, unpleasant as it may be. Veronica is pregnant; realizing her child was likely conceived by a very human-looking Brundlefly, she insists that Stathis arrange an abortion. Cronenberg himself plays the gynecologist. Blood is smeared on Veronica’s gown with Dr. Cronenberg between her legs, insisting there is more inside of her that she needs to push out. As she does, attendants begin screaming as the abortionist removes a massive, convulsing larva from inside her. This is, of course, just Veronica’s nightmare, but it proves an important point: that abortion, surgery, or on a more basic level willpower to change the body, can overcome naturally occurring physical processes. The mind can take action to destroy a physical progression, just as liposuction, cosmetic surgery, or organ transplants reinforce or work to “better” the body.

Brundle, too, attempts to alter his monstrous form via technology, perhaps because, as a former student of intellect, he is so attached to his mind. More so than ever, he has become insect, an encased persona inside irregular chunks of mutated tissue. He is barely recognizable. Moreover, his grotesque physical emergence as the insect-human Brundlefly begins to affect his mental state, further strengthening the idea that mind and body are unavoidably linked. He resolves that to cure himself, a pure human subject must teleport with him, and therein fuse his or her genetic material with his own, weeding out the insect parts. Who better to connect with on a genetic level than Veronica? Once again, technology is meant to influence the body, just as it spliced Brundle and fly together, it is now meant to splice Brundle and fly and Veronica and unborn child.

Brundle, too, attempts to alter his monstrous form via technology, perhaps because, as a former student of intellect, he is so attached to his mind. More so than ever, he has become insect, an encased persona inside irregular chunks of mutated tissue. He is barely recognizable. Moreover, his grotesque physical emergence as the insect-human Brundlefly begins to affect his mental state, further strengthening the idea that mind and body are unavoidably linked. He resolves that to cure himself, a pure human subject must teleport with him, and therein fuse his or her genetic material with his own, weeding out the insect parts. Who better to connect with on a genetic level than Veronica? Once again, technology is meant to influence the body, just as it spliced Brundle and fly together, it is now meant to splice Brundle and fly and Veronica and unborn child.

Cronenberg often utilizes technology as a tool to manipulate the body; whether it acts to silence, entice, or enhance the body depends on the subject and the film. For his 1996 movie Crash, a difficult picture (to say the least) that explores the link between sexuality and car crashes, his antagonist of sorts, Vaughan (Elias Koteas), believes “The car crash is a fertilizing rather than a destructive event.” He seeks to reform the human body through technology, via auto wrecks, finding something beautiful and chaotic in the process. One of Vaughan’s followers, played by Rosanna Arquette, sports a makeshift vagina on her upper leg, made by folds of scar tissue flapped from such a wreck. Similarly, in eXistenZ, Cronenberg’s most purely entertaining science-fiction yarn, videogamers link to a living game-pod through an umbilical-like cord that connects to a hub in the player’s lower back, called a bio-port. Bio-port installation is a mild surgical process, which Cronenberg suggests could be performed at shopping malls. Jude Law’s character asks his costar Jennifer Jason Leigh why it is that bio-ports resist infection, as they open directly into the body—she responds simply by opening her mouth, signifying how all orifices open into the body.

Cronenberg’s brand of horror begins with humanity, which consists of life, death, and sex in equal parts, without any of which the human race could not survive. Certainly, all are present in his films, especially The Fly. His cinematic discussion, if we look at it without considering the plots or images from his movies, may even seem typical—his themes of the body are even commonplace. Cronenberg’s politics are classic arguments, though they are fought with potent imagery of organic disintegration and sexual revulsion. Even his technologies, what would otherwise be cold mechanisms, seem to have a heartbeat in his films: a bone gun that shoots teeth or a wriggling game pod from eXistenZ; orgasmic typewriters that excrete euphoria-inducing discharge in Naked Lunch; and James Woods’ television in Videodrome that pulsates, even moans and excites when touched.

Cronenberg’s brand of horror begins with humanity, which consists of life, death, and sex in equal parts, without any of which the human race could not survive. Certainly, all are present in his films, especially The Fly. His cinematic discussion, if we look at it without considering the plots or images from his movies, may even seem typical—his themes of the body are even commonplace. Cronenberg’s politics are classic arguments, though they are fought with potent imagery of organic disintegration and sexual revulsion. Even his technologies, what would otherwise be cold mechanisms, seem to have a heartbeat in his films: a bone gun that shoots teeth or a wriggling game pod from eXistenZ; orgasmic typewriters that excrete euphoria-inducing discharge in Naked Lunch; and James Woods’ television in Videodrome that pulsates, even moans and excites when touched.

His visual sense and the materialization thereof is anything but routine, although as suggested, one can read The Fly’s conflict in terms of a contemporary romance story. Consider this parallel: Replace Brundle with an alcoholic or drug addict, high on his substance of choice, with his faithful Veronica standing by and watching as the vice changes into a horrible illness. She runs when Brundle begins to insist that she too participate. She resists, and after time, she sees that Brundle’s habit has expanded into a debilitating addiction. She even attempts to detach from him through her attempted abortion. All at once, Brundle crashes back into her life, preventing the abortion and forcing her to eventually cut all ties from him to escape, however painful. The film’s final scene marks the emotional height in the story, ending suddenly with the lovers tragically separated. Veronica cuts her ties, but only after Brundle accepts that he has become a monster. Any number of melodramas follow the same basic outline.

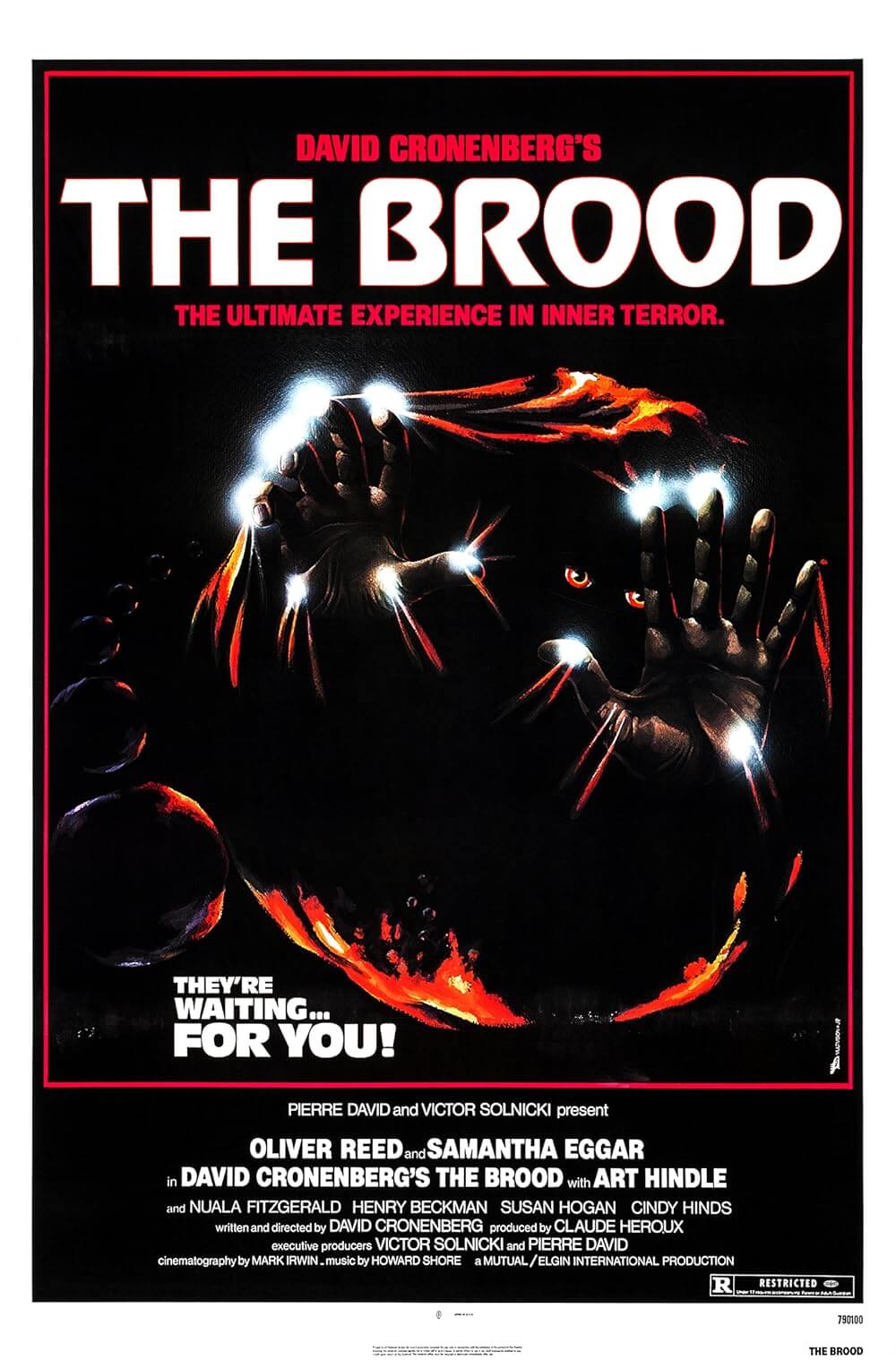

Cronenberg may be one of the few contemporary servants of the auteur theory, which was established in the 1960s by French film theorists like François Truffaut and André Bazin. Requirements of an auteur include a consistent tone or subject throughout an entire oeuvre, coupled by a director’s complete control over each aspect of a production. Cronenberg’s bodily preoccupation has created him his own subgenre: biological horror. Or, in some cases, as with eXistenZ or Scanners, science-fiction with organic science. His plots may range from operatic drama in M. Butterfly to damaged identical twins in Dead Ringers, but his filmic mannerisms and unconscious currents flow through every disturbing, remarkable picture.

Cronenberg may be one of the few contemporary servants of the auteur theory, which was established in the 1960s by French film theorists like François Truffaut and André Bazin. Requirements of an auteur include a consistent tone or subject throughout an entire oeuvre, coupled by a director’s complete control over each aspect of a production. Cronenberg’s bodily preoccupation has created him his own subgenre: biological horror. Or, in some cases, as with eXistenZ or Scanners, science-fiction with organic science. His plots may range from operatic drama in M. Butterfly to damaged identical twins in Dead Ringers, but his filmic mannerisms and unconscious currents flow through every disturbing, remarkable picture.

Cronenberg does as Seth Brundle suggests: “I build bodies… I take them apart and put them back together again.” His films show us the fragility of life as it relates to the body, mind, and sexuality—granted, his theories are proven through the use of extremes, but these extremes speak to crucial themes of self-understanding. Cronenberg attempts to assess humanity through dissection, in metaphorical terms and otherwise. The Fly is the director’s most embossed work, representing the body and distortions thereof in striking visual language. His mind-body dichotomy literally fleshes-out how anatomy and psychology remain unable to integrate and successfully coexist, and yet remain unwaveringly connected. The Fly offers a horrifying possibility: the body revolting against the mind with the mind unable to assemble any control. Brundle deflowers human arrogance over the flesh, with the mutating Brundlefly an allegory for our own physical woes, awakening us to the body’s often ignored wealth.

Bibliography:

Beard, William. The Artist as Monster: The Cinema of David Cronenberg. Toronto; Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, c2006.

Mark Browning. David Cronenberg: Author or Filmmaker? Bristol; London: Intellect, Ltd., 2007.

Cronenberg on Cronenberg. Edited by Chris Rodley. London; Boston: Faber and Faber, 1992.

Rene Descartes. Meditations on First Philosophy. Translation: Donald A. Cress. Indiana: Hackett Publishing Company, 1993.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review