The Definitives

The Fallen Idol (1948)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

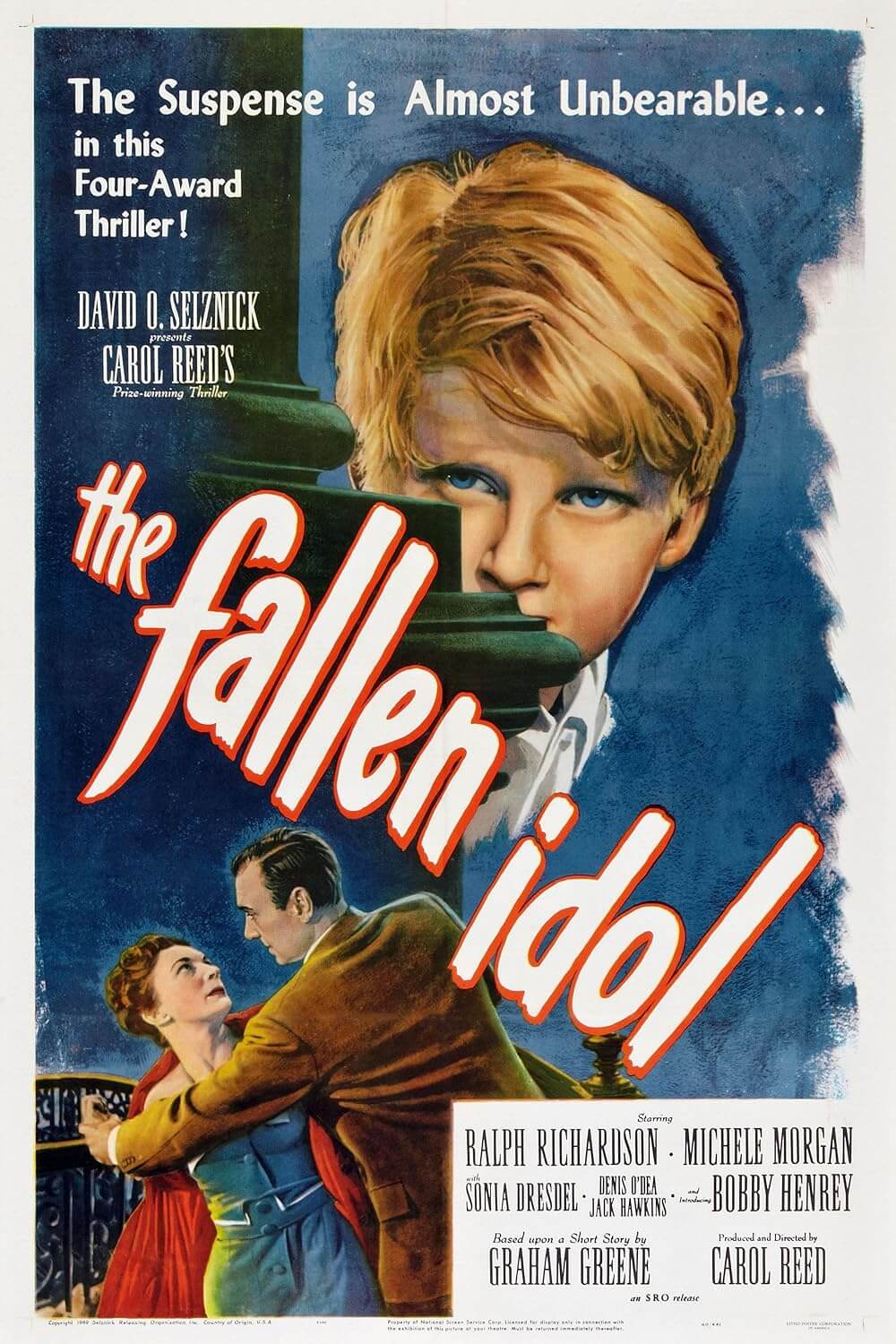

In The Fallen Idol, director Carol Reed situates the viewer into an ironic dual perspective. From the vantage point of Phillipe, the lonely nine-year-old son of the French ambassador in London, the viewer glimpses the secret world of adults, namely that of the boy’s butler and friend, Baines. Phillipe watches closely, admiringly, discovering Baines’ personal secrets; though, he looks without seeing. Misinterpreted behaviors and childhood uncertainty fuel confusion, lies, and well-meaning but foolish cover-ups. At the same time, Reed’s audience watches, reading the situations with an experience Phillipe has not yet acquired, writhing as the boy’s innocent perspective leads to dreadfully real consequences for his adult friend. Released in 1948, The Fallen Idol is a murder mystery in which no murder has been committed; rather, it has been assumed by the child’s eye. For much of the film, the audience alone knows what happened. Our awareness of the truth notwithstanding, an anxious and comical sort of thriller unfolds from false impressions, perpetuated deceptions, and shared secrets. Through the film’s wit and astoundingly genuine performances, Reed explores the dark moral dubiety that emerges sometime between the end of childhood and the beginning of adulthood. His thematically rich, dizzying entertainment muses over the complicated relationships between children and adults, truth and lies, guilt and innocence, freedom and imprisonment, and from them uncovers a biting sense of disillusion.

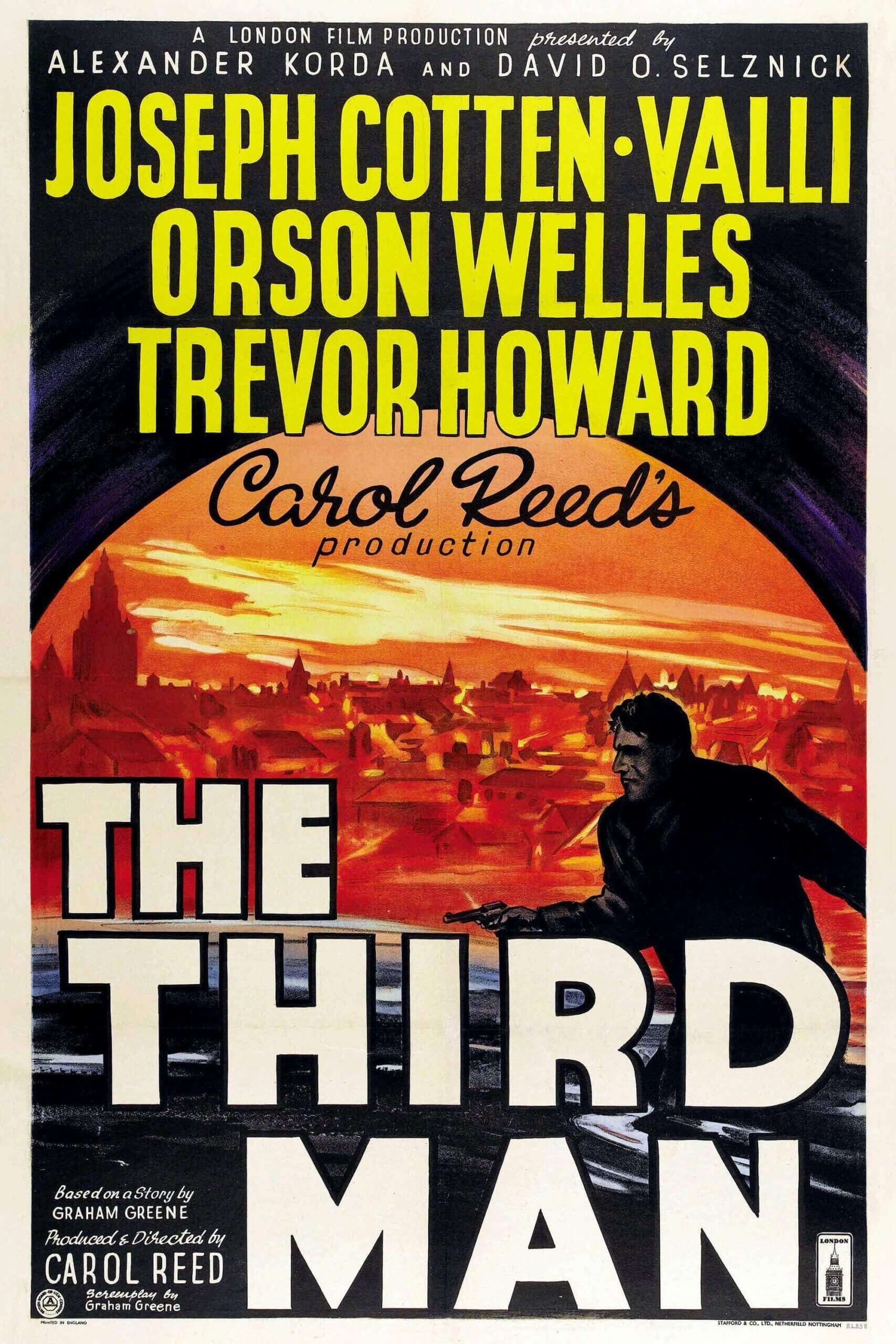

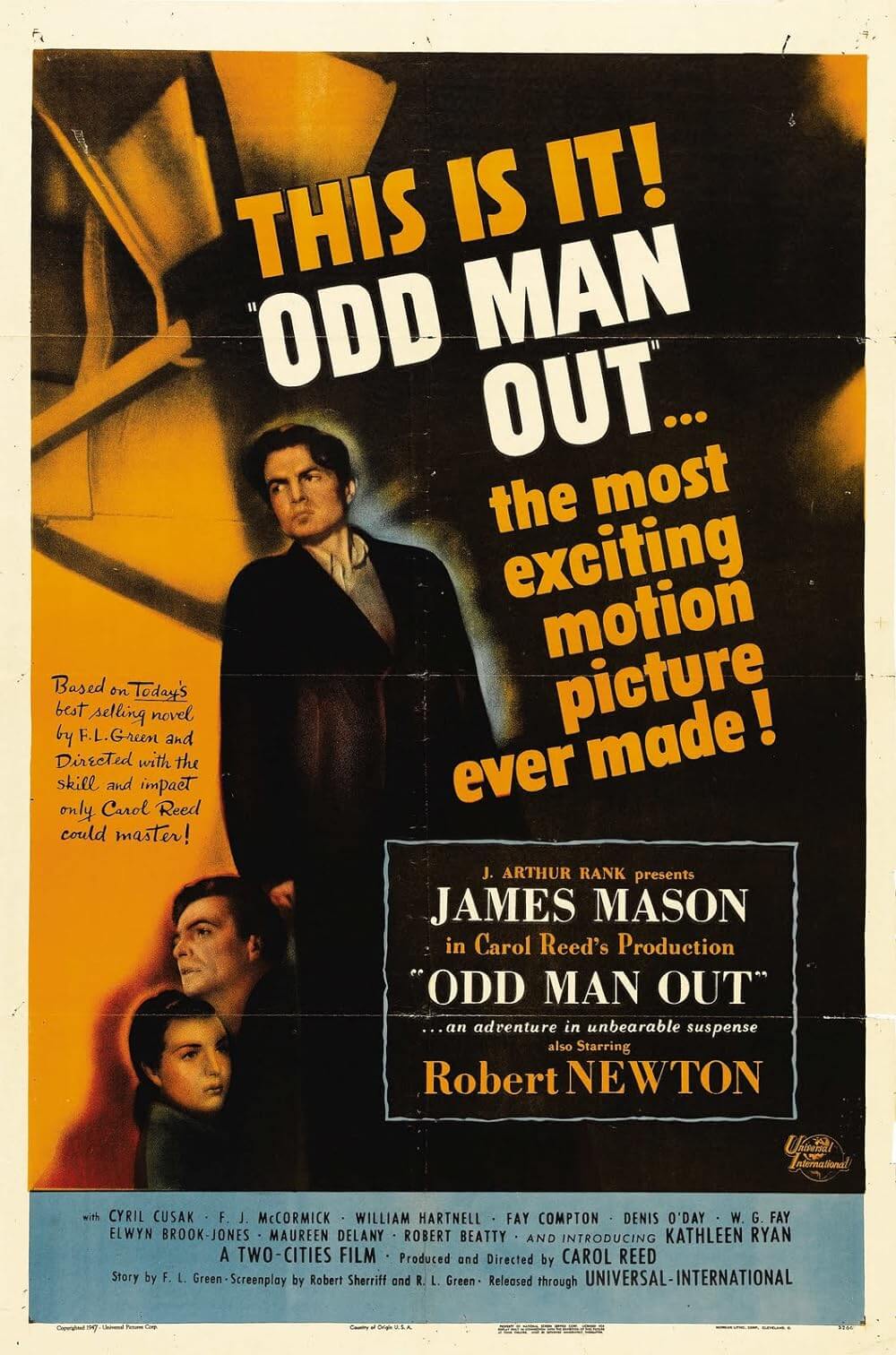

Despite recent reassessments of his work, Carol Reed never seems to get enough attention as a filmmaker. He was born in Putney in 1906 to a single mother who provided for six children, including Reed’s sister and four brothers. He abandoned school at sixteen for a short-lived career as a chicken farmer in the United States before returning to England to become an actor. Working at British Lion Pictures under Edgar Wallace (writer of King Kong, 1933), Reed soon became a dialogue director, and eventually assistant director, at Ealing Studios. His solo directing debut, the youth adventure Midshipman Easy (1935), was followed by a variety of comedies, crime stories, and dramas for which he was commissioned by a wide range of British studios. Reed’s reputation as a major talent emerged with his wartime films, especially 1940’s The Stars Look Down and Night Train to Munich, made under MGM and Twentieth Century-Fox’s British divisions respectively. He continued making renowned successes in the postwar era, his most furtive period, with Odd Man Out (1947) and later The Third Man (1949) for Alexander Korda’s production company London Films. The Fallen Idol was released between those two postwar masterpieces and would be the first of five pictures Reed made for Korda.

Given Reed’s lack of regular collaborations with, say, a consistent series of writers or genres, assigning authorship to his work has often proved difficult for biographers and scholars. Reed jumped around from genre to genre and avoided committing himself to a single studio. Although he repeatedly worked with the same cinematographers, such as Robert Krasker or Oswald Morris, their output remained diverse. Morris, for instance, shot Reed’s wartime romance The Key (1958), his spy yarn Our Man in Havana (1959), and the musical Oliver! (1968). In fact, Reed disliked the notion of directorial authorship and believed that a filmmaker should serve the story, while at the same time, he sought “something exactly the opposite from what I’ve just done.” In an interview with Charles Thomas Samuels, Reed explained, “I know that there are great directors, like Visconti and Bergman, who have a certain view of life, but I don’t think that director who knows how to put a film together needs to impose his ideas on the world.” Reed remained modest in his views toward filmmaking, both in terms of his philosophy toward authorship and his on-set presence, even after his knighthood in 1952.

Given Reed’s lack of regular collaborations with, say, a consistent series of writers or genres, assigning authorship to his work has often proved difficult for biographers and scholars. Reed jumped around from genre to genre and avoided committing himself to a single studio. Although he repeatedly worked with the same cinematographers, such as Robert Krasker or Oswald Morris, their output remained diverse. Morris, for instance, shot Reed’s wartime romance The Key (1958), his spy yarn Our Man in Havana (1959), and the musical Oliver! (1968). In fact, Reed disliked the notion of directorial authorship and believed that a filmmaker should serve the story, while at the same time, he sought “something exactly the opposite from what I’ve just done.” In an interview with Charles Thomas Samuels, Reed explained, “I know that there are great directors, like Visconti and Bergman, who have a certain view of life, but I don’t think that director who knows how to put a film together needs to impose his ideas on the world.” Reed remained modest in his views toward filmmaking, both in terms of his philosophy toward authorship and his on-set presence, even after his knighthood in 1952.

Nevertheless, as Reed scholar Peter Evan Williams notes, the director’s films inevitably show unconscious thematic patterns. Reed often sought to “make sense through art of a world ruled by violence and chaos.” Certainly this is true of The Third Man, where Holly Martens arrives from America to find that his friend Harry Lime has exploited the health of innocent children for Black Market profits. Or The Agony and the Ecstasy (1965), where Michelangelo suffers under Pope Julius II to paint the Sistine Chapel. Reed’s characters often exist in troubled relationships, divided between the outward and the inward, and with little hope of escaping that instability. Perhaps this explains why Reed’s endings were often quite tragic or, at the very least, not optimistic. Film scholar Raymond Durgnat called Reed “the most imposing pessimist” working in British cinema. A recurrent pessimism toward fatherly figures is among the more prevalent themes in Reed’s films, leading to an autobiographical insight about Reed’s own absent father, whom Reed avoided discussing and distanced himself from throughout his life. The theme is evidenced in the deceitful and misleading figures of Fagan in Oliver! or Lime in The Third Man, the cruel Pope Julius II in The Agony and the Ecstasy, the broken family in Trapeze (1956), and of course the relationship between Baines and Phillipe in The Fallen Idol.

While many film critics in the U.S. and abroad first took notice of Reed with Night Train to Munich or even later with Odd Man Out, author Grahame Green recognized the director’s talent as early as Midshipman Easy. To escape the looming world war and his deadlines as a novelist, Greene wrote upwards of 400 film reviews between 1935 and 1940 for publications such as Spectator and Night and Day, and his assessments of Reed’s work were almost always favorable given the director’s uses of form. Writing about his early films, Greene noted Reed’s “literary intelligence” and cited how the director had “more sense of the cinema than most veteran British directors.” During this time, Korda’s London Films was renowned for their sophisticated costume dramas (Rembrandt, 1936) and impressive production values (Thief of Bagdad, 1940). Having collaborated with Greene on the 1937 thriller The Green Cockatoo, Korda planned to adapt the author’s short story The Basement Room from 1935 and, after seeing Odd Man Out, courted Reed for the job. Korda introduced the director to Greene, as the two shared an interest in moral ambiguities, the human capacity for deceit, and the erosion of ideals. It would be the first of three Greene-Reed collaborations, followed by The Third Man (filmed the same year), and finally Our Man in Havana.

The Fallen Idol sees through the eyes of Phillipe—wonderfully played by Bobby Henrey, a first-time performer who retired from his acting career two years later. Left in the care of the embassy’s staff for the weekend, Phillipe finds himself embroiled in the personal drama of his friend, the butler Baines (Ralph Richardson), who lives in the embassy’s basement apartment with his wife, Mrs. Baines (Sonia Dresdel), the embassy’s chief housekeeper. Baines has been having an affair with another employee, the secretary Julie (Michèle Morgan). The affair and marital discord are all spied from Phillipe’s fidgety viewpoint, colored by his admiration for Baines and his uncomprehending perspective. He scampers around the massive embassy, clutching and poking his head through the banister’s balustrades, watching from a distance with an undeveloped sense of the world—a place where his imagination and admiration for Baines rule. When Phillipe catches Baines and Julie together at a modest tea room, he accepts Baines’ explanation that she is his niece. But Mrs. Baines learns of her husband’s affair and, when trying to catch them in the act by looking through a tilting window, she slips and falls to her death from the window sill. Phillipe believes Baines pushed her and, to protect his friend, he tells a series of lies to the police. This perpetuates a tense murder investigation, headed by Chief Inspector Crowe (Denis O’Dea). At last, any suspicion of Baines’ guilt is put to rest with the discovery of Mrs. Baines’ footprints near the window.

The Fallen Idol sees through the eyes of Phillipe—wonderfully played by Bobby Henrey, a first-time performer who retired from his acting career two years later. Left in the care of the embassy’s staff for the weekend, Phillipe finds himself embroiled in the personal drama of his friend, the butler Baines (Ralph Richardson), who lives in the embassy’s basement apartment with his wife, Mrs. Baines (Sonia Dresdel), the embassy’s chief housekeeper. Baines has been having an affair with another employee, the secretary Julie (Michèle Morgan). The affair and marital discord are all spied from Phillipe’s fidgety viewpoint, colored by his admiration for Baines and his uncomprehending perspective. He scampers around the massive embassy, clutching and poking his head through the banister’s balustrades, watching from a distance with an undeveloped sense of the world—a place where his imagination and admiration for Baines rule. When Phillipe catches Baines and Julie together at a modest tea room, he accepts Baines’ explanation that she is his niece. But Mrs. Baines learns of her husband’s affair and, when trying to catch them in the act by looking through a tilting window, she slips and falls to her death from the window sill. Phillipe believes Baines pushed her and, to protect his friend, he tells a series of lies to the police. This perpetuates a tense murder investigation, headed by Chief Inspector Crowe (Denis O’Dea). At last, any suspicion of Baines’ guilt is put to rest with the discovery of Mrs. Baines’ footprints near the window.

Greene and Reed worked together closely on adapting The Basement Room, which the author believed unfilmable. But Reed’s alterations to the material were essential, in that they established the film’s dramatic irony. In Greene’s original story, written over the course of a five-day boat voyage, Phillipe witnesses Baines struggle with his wife and push her down the stairs to her death, and the boy’s subsequent lies to protect his friend ultimately betray Baines. The film changes the crime of passion from Greene’s short story into an accidental death. The fortuitous incident heightens the film’s dramatic stakes, making the subsequent investigation into Baines even more nerve-wracking due to his innocence. In the film, Baines and Julie are uncertain how Mrs. Baines has died, while Phillipe, watching Baines and his wife struggle from an outside vantage point, sees the events unfold from the fire escape. He races down the fire escape stairs to get a better look, with crucial sections of the confrontation occurring between floors where the boy cannot see. Phillipe’s imagination assumes the worst, and he resolves to protect his friend.

More than any other Reed picture, The Fallen Idol devotes the lion’s share of its runtime to a child actor, and Henrey’s short attention span during the shoot presented a problem for Reed. But the director insisted on a harmonious approach to remain unintimidating to his young star. Reed’s typical presence on the set was calm and relaxed. He wanted everyone to feel encouraged and, if mistakes were made or a take was spoiled, he made excuses so as not to assign blame. Perhaps because Reed’s career in film began as a performer, he was more open to on-set improvisation and errors. Still, his patience was tested by Henrey’s inexperience as a child actor—a virtue in this case, as Henrey never seems overly self-aware in his performance, unlike most child actors. He behaves, quite simply, like a child. Reed employed several tactics to achieve this. Above all, he kept Henrey’s attention focused and prevented him from succumbing to boredom. During the scene where Inspector Crowe sits Phillipe down to answer some questions, Reed gave the boy a piece of string to occupy his hands. In another scene that required Henrey to smile, the child refused, and Reed hired a magician to entertain him and get the shot. Although the director sometimes used hundreds of feet of film to achieve a single usable take, the performance, or Reed’s subtle manipulation of Henrey’s seemingly comfortable, rather outstanding onscreen presence, speaks to the director’s foresight. It also speaks to the power of editing. Reed turned Phillipe into a fully realized character by capturing Henrey’s momentary reactions, gestures, and sometimes unconnected line deliveries, and then he assembled them in the editing room. His approach to working with children served him again later with the child actors in The Third Man, A Kid for Two Farthings, and Oliver!.

When it was released in England in 1948, critics garnered The Fallen Idol with almost collective praise, most citing Henrey’s performance. The Sunday Chronicle called Henrey “the Greatest Kid since Coogan,” referring to Jackie Coogan, child star of Charles Chaplin’s The Kid (1921). The Observer praised Reed, calling the film “the best thing he has ever done.” At the Venice Film Festival, Greene won the Best Screenplay award, and though he never liked the title (he preferred the original title or The Lost Illusion as an alternative), it was the author’s favorite among his screenplays. David O. Selznick financed the United States release of The Fallen Idol and would later back Reed and Korda’s production of The Third Man. But the Production Code Administration refused to approve the release until Reed cut several sexual implications in the film. For instance, after Phillipe witnesses what he thinks is a murder, he runs away into the night. A police officer finds him and brings him to the station, where other officers are booking a prostitute, Rose (Dora Bryan). To persuade Phillipe to reveal where he lives, the officers enlist Rose, who extracts the information by speaking to Phillipe like one of her Johns (“Shall I take you home?”). When she finally discovers that Phillipe lives at the embassy, she exclaims, “Oh, I know your daddy!” The PCA demanded the line be rewritten, as well as later implications that Baines and Julie had slept together. One suspects that the PCA must have also objected to the zoo scene in which Phillipe, standing outside the monkey enclosure, asks an embarrassed Baines and Julie, “What are they doing?”—to which the adults turn away, giggling.

When it was released in England in 1948, critics garnered The Fallen Idol with almost collective praise, most citing Henrey’s performance. The Sunday Chronicle called Henrey “the Greatest Kid since Coogan,” referring to Jackie Coogan, child star of Charles Chaplin’s The Kid (1921). The Observer praised Reed, calling the film “the best thing he has ever done.” At the Venice Film Festival, Greene won the Best Screenplay award, and though he never liked the title (he preferred the original title or The Lost Illusion as an alternative), it was the author’s favorite among his screenplays. David O. Selznick financed the United States release of The Fallen Idol and would later back Reed and Korda’s production of The Third Man. But the Production Code Administration refused to approve the release until Reed cut several sexual implications in the film. For instance, after Phillipe witnesses what he thinks is a murder, he runs away into the night. A police officer finds him and brings him to the station, where other officers are booking a prostitute, Rose (Dora Bryan). To persuade Phillipe to reveal where he lives, the officers enlist Rose, who extracts the information by speaking to Phillipe like one of her Johns (“Shall I take you home?”). When she finally discovers that Phillipe lives at the embassy, she exclaims, “Oh, I know your daddy!” The PCA demanded the line be rewritten, as well as later implications that Baines and Julie had slept together. One suspects that the PCA must have also objected to the zoo scene in which Phillipe, standing outside the monkey enclosure, asks an embarrassed Baines and Julie, “What are they doing?”—to which the adults turn away, giggling.

The postwar era found several filmmakers using children and broken families as metaphors for innocence lost in the wake of World War II. David Lean adapted Great Expectation (1946) and Oliver Twist (1948), and Anthony Asquith made The Winslow Boy (1948)—each a story about the tragic dissolution of children in a world of adults. Similarly, Reed’s film portrays three fractured families: Phillipe’s family, with two absent parents; the marriage of Baines and Mrs. Baines, broken by his infidelity and her need for loveless order; and the makeshift family between Phillipe and Baines, with the butler serving as both parent and older brother to the boy. Greene and Reed suggest the idealized vision of the happy family is an illusion—itself an idol that inevitably crumbles from the reality of love affairs, broken promises, unkept secrets, and ultimately death. Surely death is the grimmest reality of all in The Fallen Idol, as the doctor inspecting Mrs. Baines’ corpse remarks, “Death is like a business. It has to be attended to.” But Reed treats even death with a sense of irony, as the embassy’s two comical cleaning ladies snoop around the site of Mrs. Baines’ fall, debating whether they’ll find blood on the stairs. “There might be a little if the bone came through.”

Reed’s precision as a filmmaker is evidenced in his narrative economy, the speed with which he relays information, and his accentuation of the story with sharp uses of form. Teamed with Georges Périnal, the premier cinematographer for Korda’s London Films, Reed uses his oft-employed tilted angles and chiaroscuro lighting to reflect Phillipe’s perception of a given scene. When Phillipe runs out after witnessing what he believes to be a murder, his journey down wet, shadowy cobblestone streets against a harsh light in the rear distance recall Harry Lime escaping on the streets of Vienna. Or earlier, Phillipe enjoys a delirious game of hide-and-seek with Baines and Julie, and Reed’s use of Dutch tilts conveys the dreamy atmosphere of Vincent Korda’s set designs for the embassy—the primary location throughout the film. The embassy’s ornate furnishings have been draped in sheets for the weekend. Baines wisps the covers about and then runs to flicker the light switch to give the already Gothic setting its due lightning. While Phillipe hides, he sees a shadow moving in the dark and, not realizing it’s Mrs. Baines, screams, thinking he saw a ghost. In the child’s mind at night, the house is haunted. More than a house of shadows and ghosts, the embassy’s reception area looms over the film as Phillipe’s larger-than-life enclosure, with its grand staircase and the marble checkerboard floor—reflecting the film’s thematic patterns: the truth and lies, maturity and immaturity, freedom and confinement.

To be sure, enclosures have a recurrent presence in The Fallen Idol. Phillipe remains a neglected prisoner within the embassy, and he tends to see others in terms of freedom and confinement. As he’s ignored by his father, and his mother has been away for several months due to a psychological condition, the spindles on the banister act like prison bars. He peers through them down at Baines, who looks up at his friendly accomplice with a series of winks, goofy gestures, and secret jokes to entertain the boy, while also going about his duties with his employers never the wiser. To maintain a sense of control within his confining world, Phillipe keeps a pet snake named McGregor, hiding it from the disapproving Mrs. Baines in a small box behind a loose brick. He treats McGregor with tenderness, perhaps sympathizing with the very creature he keeps confined. Phillipe assumes everyone is a prisoner of some kind. When Baines and Julie take the boy to the London Zoo, he offers food to a chap behind a gatelike turnstile, unaware, in a characteristic Reed irony, that the man is only leaving the restroom and is not in a cage.

To be sure, enclosures have a recurrent presence in The Fallen Idol. Phillipe remains a neglected prisoner within the embassy, and he tends to see others in terms of freedom and confinement. As he’s ignored by his father, and his mother has been away for several months due to a psychological condition, the spindles on the banister act like prison bars. He peers through them down at Baines, who looks up at his friendly accomplice with a series of winks, goofy gestures, and secret jokes to entertain the boy, while also going about his duties with his employers never the wiser. To maintain a sense of control within his confining world, Phillipe keeps a pet snake named McGregor, hiding it from the disapproving Mrs. Baines in a small box behind a loose brick. He treats McGregor with tenderness, perhaps sympathizing with the very creature he keeps confined. Phillipe assumes everyone is a prisoner of some kind. When Baines and Julie take the boy to the London Zoo, he offers food to a chap behind a gatelike turnstile, unaware, in a characteristic Reed irony, that the man is only leaving the restroom and is not in a cage.

Phillipe identifies with Baines as a fellow prisoner under the warden Mrs. Baines, but also as a heroic and childlike adult. Surely, Baines is something of a child himself—he enjoys telling Phillipe false exploits from his time as an African big game hunter, often forgetting his own tall tales. Phillipe listens to Baines’ stories, his face cupped in his hands, mesmerized that his butler could be so gallant. But Phillipe must remind Baines of the story he told about killing an African man in self-defense—a story that becomes difficult to explain later during the police inquiry. Baines’ clowning with Phillipe represents the delineation of their own shared world, providing Baines another escape (in addition to Julie) from his domineering wife, and Phillipe with an escape from loneliness (aside from McGregor). Although this dynamic remains unspoken for the early part of the film, the enemy lines are demarcated when Mrs. Baines accuses Phillipe of spoiling his meal with a snack. Of course, Baines has given the boy cakes at the tea room during his clandestine meeting with Julie. Though, covering for Baines, Phillipe denies having spoiled his meal. The moment comes to a head when Mrs. Baines orders the boy to his room and her “because I say so” reasoning is met with Phillipe’s undertoned declaration: “I hate you.”

Although Baines protects the boy from Mrs. Baines—such as when he slides the box with McGregor across the dining table, knowing that if his wife finds the snake, she will kill it—Baines remains a child in a world of adults. When Inspector Crowe and Detective Ames (Jack Hawkins) arrive to question Baines about his wife’s death, the butler’s confident manipulation of Phillipe’s confidence descends into a nervous rambling with officials. Only an actor of Richardson’s skill, most frequently deployed on the London stage, could capture such stark changes in the same character. He may act as Phillipe’s brave protector, but Baines is no mastermind and certainly maintains no semblance of cucumber cool when faced with questioning. He paces back and forth, visibly sweats, stumbles over his words, and recants statements when confronted with alternate details. “Of course,” he says, “that’s what I meant.” Like a child who tries to cover a white lie with even more lies, Baines makes himself look guiltier, more culpable with each statement, despite Julie encouraging him to simply tell the truth. Likewise, Phillipe’s lies to cover for Baines become increasingly outlandish, much to the incredulity of the authorities. It is only when Det. Ames discovers a footprint in some potting soil on the ledge where Mrs. Baines fell that the police uncover the truth—not by any statements made by either Baines or Phillipe.

Given the circumstances of Baines’ infidelity, it may be tempting to empathize with Mrs. Baines outside of the film’s perspective, which aligns with Phillipe and, to a lesser degree, Baines. But her place as a sympathetic victim of an adulterous husband is countered by her cruelty, as McGregor’s fate in the furnace attests. Reed’s treatment of Mrs. Baines recalls Mrs. Danvers (Judith Anderson) from Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca (1940). Reed has often been associated with the films of Hitchcock. Night Train to Munich seems to exist in the same world as Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes (1935), including star Margaret Lockwood (who made seven films with Reed) and the reappearance of Charters and Caldicott (Basil Radford and Naunton Wayne), a pair of cricket-obsessed Englishmen. Later, The Third Man would be accused of adopting a Hitchcockian style. The Fallen Idol evokes stylistic and thematic elements of Rebecca in their shared Gothic settings. The frigid and cruel Mrs. Baines looks over the embassy, while Rebecca’s estate, Manderlay, has the devious Mrs. Danvers. Both characters oversee childish adults, as Mrs. Danvers must attend to the naïve and mousy Joan Fontaine. Not only must Mrs. Baines endure the rambunctious Phillipe, but also the immaturity of her husband. However, Mrs. Baines cannot shake answers out of Baines as she does Phillipe. Her violent treatment of the boy just before her death, including harsh slaps, seals her villainy for Phillipe, Baines, and the audience.

Given the circumstances of Baines’ infidelity, it may be tempting to empathize with Mrs. Baines outside of the film’s perspective, which aligns with Phillipe and, to a lesser degree, Baines. But her place as a sympathetic victim of an adulterous husband is countered by her cruelty, as McGregor’s fate in the furnace attests. Reed’s treatment of Mrs. Baines recalls Mrs. Danvers (Judith Anderson) from Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca (1940). Reed has often been associated with the films of Hitchcock. Night Train to Munich seems to exist in the same world as Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes (1935), including star Margaret Lockwood (who made seven films with Reed) and the reappearance of Charters and Caldicott (Basil Radford and Naunton Wayne), a pair of cricket-obsessed Englishmen. Later, The Third Man would be accused of adopting a Hitchcockian style. The Fallen Idol evokes stylistic and thematic elements of Rebecca in their shared Gothic settings. The frigid and cruel Mrs. Baines looks over the embassy, while Rebecca’s estate, Manderlay, has the devious Mrs. Danvers. Both characters oversee childish adults, as Mrs. Danvers must attend to the naïve and mousy Joan Fontaine. Not only must Mrs. Baines endure the rambunctious Phillipe, but also the immaturity of her husband. However, Mrs. Baines cannot shake answers out of Baines as she does Phillipe. Her violent treatment of the boy just before her death, including harsh slaps, seals her villainy for Phillipe, Baines, and the audience.

Reed captures the adult world through Phillipe’s eyes and renders the simplest situations, such as the drama of Baines and Julie’s affair, even more poignant and affecting through a skewed perspective. When Phillipe finds them in the tea room, he sees Julie crying, and Baines explains she has something in her eye. Accepting this at face value, Phillipe gives his best advice: “Pull the top lid over the other one. That’s what I always do.” When Baines asks Phillipe to keep their meeting with Julie a secret from Mrs. Baines, the boy remarks, “Isn’t it exciting,” as though he’s been included in a conspiracy against his enemy. All the while, the viewer watches every scene on a dual level—from Phillipe’s standpoint, and from our awareness of the situation beyond Phillipe. Reed masterfully balances these two concurrent worlds, offering heightened moments where they intersect. A breathless sequence occurs when Baines tries to retrieve a telegram sent by Mrs. Baines, which reveals that he gave a false account to the police. But Phillipe has made the telegram into a paper airplane. As Baines reaches for the paper, the doctor on the scene tries to amuse the boy by tossing it from the staircase. The paper airplane glides over the stairs and over the heads of the police, carrying Baines’ fate within the folds of a child’s toy as it descends along with the flutes of William Alwyn’s score. The plane’s trajectory stops its childish flight when it bumps into Detective Ames, then falls to the ground.

Although Reed’s auteurism has been debated and doubted, The Fallen Idol underscores several recurrent motifs in his career, consciously or otherwise. His frequent use of child actors has never been better than the delightfully haphazard and unpolished performance by Henrey. Propelled by Greene’s material, Reed’s willingness to expose the cracks in civilization results in acrid humor. His desire to make sense of a chaotic, often fatherless world surfaces through the film’s ironic tragedy. And his regular destruction of the faith people put into others informs the title, whether Greene approved or not. The film’s shattered worldview notwithstanding, Reed transforms the material into cinematic joy through his exhilarating use of mannered form, intricate mise-en-scène, and direction of exceptional performances throughout. Greene’s usual ambition to engage his audience with accessible storytelling, yet also instill a philosophical edge, finds a perfect harmony with Reed’s sensibilities. The Fallen Idol is likewise an internal and external experience, and its duality reminds the viewer of the innocence of children and the corrupted, destructive force of adulthood.

Bibliography:

Durgnat, Raymond. A Mirror for England: British Movies from Austerity to Affluence. Praeger, 1971.

Evans, Peter William. Carol Reed. British Film Makers. Manchester University Press, 2005.

Greene, Graham, and John Russell Taylor (Editor). The Pleasure Dome – Graham Greene: The Collected Film Criticism, 1935-40. Oxford University Press, 1987.

Moss, Robert F. The Films of Carol Reed. Columbia University Press, 1987.

Samuels, Charles Thomas. Encountering Directors: Interviews. Capricorn Books, 1972.

Wapshott, Nicholas. A Man Between: A Biography of Carol Reed. Chatto & Windus, 1990.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review