The Definitives

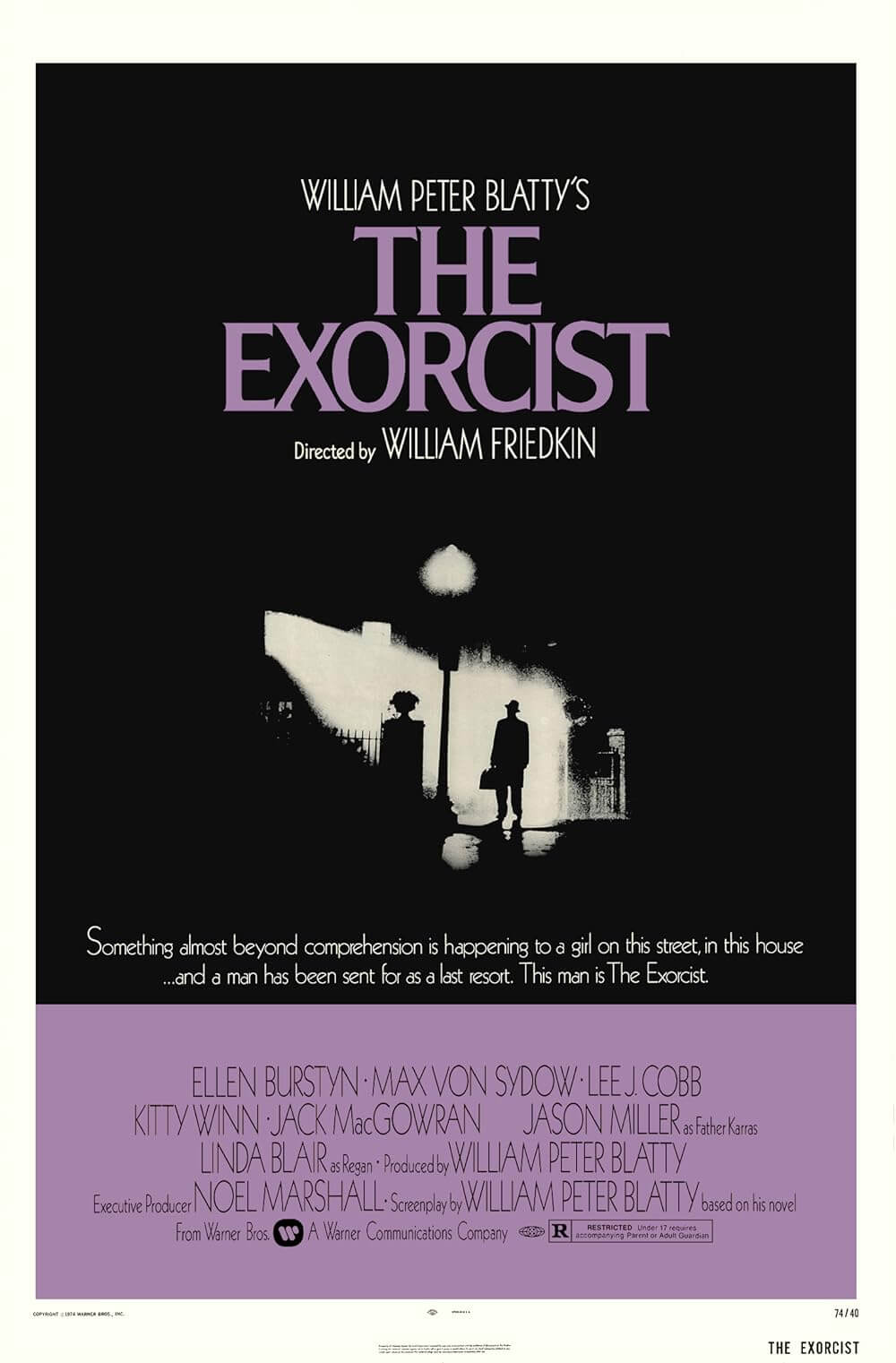

The Exorcist (1973)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Spirituality has never had a more unlikely ally than William Friedkin’s enduring shocker The Exorcist. No matter the belief system of the viewer, the film’s haunting and ingeniously crafted verisimilitude suspends all doubts, leaving even the most devout skeptic shaken by the concept of possession and open to the possibility of faith. Based on William Peter Blatty’s novel, published in 1971, Friedkin’s film enhances the material through practical effects and breakneck pacing to make the thoughtful book into an assaulting, yet oddly spiritual experience. The director’s horrifyingly maintained assault of the viewer’s senses and faith leaves the audience subject to devilish, claustrophobic torment that makes the resultant spiritual awakening all the more powerful. As this outcome has not diluted one iota since its debut, it earns the oft-used title of the scariest film ever made.

Upon its initial release in 1973, the “vulgar spectacle” onscreen offended the moral populace of religious devotees around the world, but also touched, or rather scathed, everyone else. Reports of fainting, heart attacks, miscarriages, and no end of vomiting fuelled media hysteria. Some viewers were submitted to psychiatric care after their screenings, while deaths or suicides near to a screening of the film were attributed to its unholy influence over the viewer. Murderers blamed the film for taking them over. West Germany propelled the hysteria further when they banned the picture from cinemas. The R-rating determined by the MPAA was criticized for being too lenient, as parents could still take their children to see it; religious groups believed no children should be allowed to such horror under any circumstances. Some Catholic groups praised the film for its admitted spirituality, while it was condemned as “Satanic” by others, such as evangelist Billy Graham, who declared that every frame of its celluloid was evil.

Blatty intended his novel, and the film, to confront questions of faith and the possibility of possession with a sense of veracity. A Catholic who attended the Jesuitical Georgetown University, Blatty based his book on a priest’s 1949 journal concerning the exorcism of a 14-year-old boy in Mount Rainier, whose story would later be published in the 1993 nonfiction account, Possessed by Thomas B. Allen. Though the origin case featured no projectile vomit, caused no inexplicable drops in temperature, boasted no crucifix masturbation, and offered no procession of medical examinations, the details of the case nonetheless inspired Blatty to confront his own doubts about possession within his narrative. And so, after a career of writing screen comedies like A Shot in the Dark, Blatty approached the material with an alternative perspective rooted in ‘the real’. The resulting novel gathered instant attention from Hollywood, though most studios passed on the filmic adaptation until Warner Bros. agreed to produce. Blatty’s initial, lengthy screenplay based on his novel proved “overwrought” according to Friedkin, who in turn rewrote the script with Blatty into a more concise, less symbolic version.

Blatty intended his novel, and the film, to confront questions of faith and the possibility of possession with a sense of veracity. A Catholic who attended the Jesuitical Georgetown University, Blatty based his book on a priest’s 1949 journal concerning the exorcism of a 14-year-old boy in Mount Rainier, whose story would later be published in the 1993 nonfiction account, Possessed by Thomas B. Allen. Though the origin case featured no projectile vomit, caused no inexplicable drops in temperature, boasted no crucifix masturbation, and offered no procession of medical examinations, the details of the case nonetheless inspired Blatty to confront his own doubts about possession within his narrative. And so, after a career of writing screen comedies like A Shot in the Dark, Blatty approached the material with an alternative perspective rooted in ‘the real’. The resulting novel gathered instant attention from Hollywood, though most studios passed on the filmic adaptation until Warner Bros. agreed to produce. Blatty’s initial, lengthy screenplay based on his novel proved “overwrought” according to Friedkin, who in turn rewrote the script with Blatty into a more concise, less symbolic version.

As it appears in the original cut, the story progresses at a speed that jolts the viewer with information about the characters and burgeoning evil onscreen, until the culmination with the ending’s exorcism. The film’s enduring themes of good versus evil, science versus religion, new versus old, and faith versus doubt come to fruition within the first scenes of the prologue in Iraq. Father Merrin (Max von Sydow) joins in the unearthing of an ancient tomb in Nineveh; there he finds a small carving of Pazuzu, a wind demon from ancient Mesopotamian mythology. Something heavy weighs on him, and he seeks out a large standing sculpture of Pazuzu. There, positioned opposite Merrin within the frame, looms a massive, man-sized sculpture of demonic origins. The shot foreshadows the forthcoming battle between Merrin and the demon, but also establishes thematic confrontations that appear throughout the film.

This ancient evil positions itself against the modern when the story moves to Washington D.C., where actress Chris MacNeil (Ellen Burstyn) hears the scratching sound of rats in her attic. Her 12-year-old daughter, Regan (Linda Blair), plays with a Ouija board; she makes the questions and “Captain Howdy” gives her the answers. Not being religious, her mother—who was based on Shirley McClaine, Blatty’s neighbor at the time, who helped get his novel its due attention—shows no concern over this behavior. Above all, she’s a pragmatist and doesn’t believe in such things. But then Regan’s behavior becomes irregular, eventually erratic, and explained away as “nerves”. First, she questions her mother’s relationship with her director, Burke Dennings (Jack MacGowran), with undue suspicion. Could Captain Howdy have been telling Regan lies to drive mother and daughter apart? Her changes advance into physical symptoms as she urinates on the carpet during her mother’s party, then violently convulses on her bed, making the entire frame impossibly shake off the ground.

Through series of grueling medical exams—including X-rays, EEG, lumbar tap, and a faint-inducing arteriogram—by baffled doctors, Regan only becomes worse. Her face has contorted into something pale and foul; she uses the vilest language, and mutilates her own body by scratching her face and genitals in the aforereferenced crucifix masturbation scene. Every scientific possibility is explored to the fullest to explain Regan’s worsening condition. Doctors recommend psychiatrists, who in turn recommend an exorcism by a Catholic priest. Chris responds with disbelief, “You’re telling me that I should take my daughter to a witch doctor?” Given the archaic view of demons established in the Iraq prologue, religion represents the superstitious, yet unknowable that cannot be explained by the modern doctors. None of them truly believe a demon has possessed Regan, merely that Regan believes it, and so the suggestion of exorcism would expel the idea of possession that has contaminated the girl.

Not even the priest commissioned fully accepts demons or exorcisms as real. Father Karras (Jason Miller) has lost his faith. He serves as a psychiatrist and confidant to the religious community, but his work grows increasingly difficult as he can no longer counsel men of the cloth in questions of faith. Weakened by his existential dilemma and guilt over the recent death of his mother, Karras becomes an unlikely choice for the MacNeils. His psychiatric and religious backgrounds seem a rational pairing, but Karras approaches Regan with disbelief at first, as his tests to verify the authenticity of her possession show doubt. He sprinkles her with what he claims is holy water and she reacts violently, but it was actually tap water. She claims she is Satan and speaks in what sounds like a foreign language that would be unknown to Regan, but the language is merely English in reverse. On the voice recording, however, Regan’s moaning and screaming in reverse produces a name: “Merrin”.

The church approves an exorcism for Regan, to be carried out by Fr. Merrin, with Fr. Karras assisting. Merrin arrives at the MacNeil house on a foggy night, silhouetted by an ominous light peering down from Regan’s bedroom window. Once again, good and evil stand in their respective position to the right and left in the frame, on opposing sides of battle. During the exorcism, Merrin warns Karras to ignore the demon’s baiting insults, which ensue as Regan’s voice becomes that of Karras’ mother, asking him why he allowed her to die. Despite witnessing the girl elevate off the bed and her head spin like a top, nothing could be more jarring for Karras than to hear his mother’s voice. Visibly shaken and emotionally compromised, Karras is asked to leave by Merrin. After a moment of rest, Karras returns to the bedroom and discovers Merrin dead, the demon giggling over its victory. Karras attacks the girl, demanding that the demon take him instead. As the demon exits the girl, it enters Karras, his eyes changing to evil yellow and his skin a deathly pale blue; but with his regained faith—his belief now in Satan, thus the Satan’s opposite, God—he overpowers the demon, his skin returning to normal as he leaps out the bedroom window to his death. Though victory comes with a sacrifice, faith and goodness ultimately prevail.

The positive spiritual message within the film was, and in some cases still is, lost on an audience terrified by Friedkin’s representation of Regan’s possession. Friedkin employed make-up artist Dick Smith and special effects supervisor Marcel Vercoutere to conceive of practical ways of achieving the horrors onscreen. Friedkin wanted only mechanical effects, as animations of the era would remove the audience from the documentarian’s sense of reality given to the story. Smith and Vercoutere built the dummy that allowed Regan’s head to spin in perhaps the film’s most remembered scene, a display that was not present in Blatty’s novel, and which the writer initially protested. An elaborate set—featuring false walls, a removable ceiling for piano wire levitation, and a ventilated window that could issue chilling gusts on cue—was built inside a refrigerated room to lower the temperature for visible breath. Regan’s demonic voice was fulfilled by Mercedes McCambridge, who chain-smoked and gargled eggs to achieve the proper rattle. Eileen Dietz took on the possessed makeup for the more graphic scenes of violent acts, as well as the subliminal faces that appear in the film’s brief, ghostly flashes throughout. This particular effect was so successful that in his assessment of the film, subliminal message scholar Wilson Bryan Key believed such rampant subliminal imagery to be authentic and not created by the filmmakers; therefore he deemed the film itself was possessed. Curiously, within his appraisal of the subliminal imagery, he notes incidents that were not in the film and were clearly imagined during his uneasy viewing.

The positive spiritual message within the film was, and in some cases still is, lost on an audience terrified by Friedkin’s representation of Regan’s possession. Friedkin employed make-up artist Dick Smith and special effects supervisor Marcel Vercoutere to conceive of practical ways of achieving the horrors onscreen. Friedkin wanted only mechanical effects, as animations of the era would remove the audience from the documentarian’s sense of reality given to the story. Smith and Vercoutere built the dummy that allowed Regan’s head to spin in perhaps the film’s most remembered scene, a display that was not present in Blatty’s novel, and which the writer initially protested. An elaborate set—featuring false walls, a removable ceiling for piano wire levitation, and a ventilated window that could issue chilling gusts on cue—was built inside a refrigerated room to lower the temperature for visible breath. Regan’s demonic voice was fulfilled by Mercedes McCambridge, who chain-smoked and gargled eggs to achieve the proper rattle. Eileen Dietz took on the possessed makeup for the more graphic scenes of violent acts, as well as the subliminal faces that appear in the film’s brief, ghostly flashes throughout. This particular effect was so successful that in his assessment of the film, subliminal message scholar Wilson Bryan Key believed such rampant subliminal imagery to be authentic and not created by the filmmakers; therefore he deemed the film itself was possessed. Curiously, within his appraisal of the subliminal imagery, he notes incidents that were not in the film and were clearly imagined during his uneasy viewing.

Goading his audience and propelling the post-release hysteria surrounding the film, Friedkin refused to deny claims that his production was haunted. He wanted people to believe what they were seeing, and so he fed the press disinformation. Friedkin told the media that Blair did all of her scenes, if only so audiences would not take themselves out of the story to look for her stuntwomen. Dietz and McCambridge eventually sued for credit, whereas Blair suffered professionally as her performance and credibility came under fire for not speaking up about Friedkin’s fibs. Reacting to Friedkin’s claims, the press insisted Blair must be mentally unstable; how else could she behave that way? Even after Dietz came forward, Blair was accused of being unbalanced. Meanwhile, Blair was left with her reputation bruised, and her back badly damaged from being tossed like a ragdoll during bed-quaking scenes. Friedkin refused to spare the authenticity of his production just to afford his actors physical comfort. While Blair’s back was damaged, Friedkin also injured Burstyn; moreover, he was said to have fired gunshots on-set to heighten tensions. Regardless of his questionable methods that sometimes reached the absurd (he told the press that the levitation scenes were achieved via “magnetic field”), the outcome was unquestionably effective.

The film opened to largely positive reviews, many declaring it a benchmark of horror filmmaking. Its detractors voiced their negative assessments even louder, however, as the potent subject matter seemed to enrage certain sensibilities. Vincent Canby of the New York Times wrote the film off as “a chunk of elegant occultist claptrap”, whereas Andrew Sarris called it “a thoroughly evil film”. Others pronounced it the best horror film ever made. Nevertheless, whether viewers engaged the material or rejected it, the picture could not be ignored. The Exorcist became an instant phenomenon, one of the top grossing films of 1973, and certainly one of the most top-earning R-rated films of all time. It was nominated for ten Oscars, winning two for Best Sound and, ironically, Blatty for Best Adapted Screenplay. Though, the notoriously troubled production remains infamous not only for the resultant effect on the audience, but for the controversy surrounding subsequent releases. Blatty wanted Friedkin to direct because, as a Jewish filmmaker with largely agnostic views on spirituality, Friedkin would know exactly how to dispel the doubts of his viewers. Warner Bros. had not considered Friedkin a suitable choice until he won his Best Directing Oscar for The French Connection; although, Blatty threatening legal action against Warner unless they hired the director he wanted surely influenced their decision. Friedkin rightfully believed the message of the film to be evident within the plot structure, whereas Blatty wanted the spirituality emphasized through palpable symbolism. Friedkin and Blatty argued endlessly during filming and the editing process about scenes that should be cut; but ultimately, Friedkin won these arguments and the film was released to his specifications.

Twenty-five years after the initial release, Friedkin, who had fallen into obscurity with a number of underwhelming releases since the mid-1980s, was convinced by Warner Bros. to revisit The Exorcist. In the interim, the film had become legend, followed by lackluster sequels and unending rip-offs. For years Friedkin bounced back-and-forth between wanting to recut the film and wanting to preserve the integrity of the original. Warner’s plans of reincorporating scenes that were previously reported “missing” now appealed to Friedkin, despite his stubborn refusal years earlier. He searched the Warner vaults for reels of footage and audio that could not, in some cases, be fully restored. In time, upon finding some of the missing footage, the director admitted that he was young when he first shot the picture, but upon reexamination he finally realized what Blatty’s book was about. This was the beginning of an unfortunate theatrical re-release called “The Version You’ve Never Seen”, eventually to be renamed “Director’s Cut” on home video.

The release of “The Version You’ve Never Seen” reawakened audiences to the intensity of the film, though several of Friedkin’s additions over-emphasize narrative themes or diminish its horrifying claustrophobic effect, while other scenes augment them. In the planning stages, not all of the scenes proposed by Friedkin and Blatty for inclusion of the re-release could be found, or not fully assembled due to missing audio reels. These scenes include footage of Regan’s birthday outing around Washington with her mother and a much-discussed alternate ending. The re-release features more medical scenes for a slower growing tension, as well as added subliminal faces flashed onscreen. These subliminal images, some of a white-faced demonic Dietz and others of the Pazuzu statue, render the effect obvious, whereas, in the original version, they created a sense of did-I-just-see-that doubt. In the re-release’s finale, Karras sees his mother in the window shutters upon his sacrifice, a detail whose meaning eludes even the filmmakers. The most publicized change was the silly “spider-walk sequence” which defuses the film’s crucial sense of isolation in Regan’s room. Overall, the unnecessary added scenes over-emphasize Blatty’s spiritual center that was already present through Karras’ character arc, turning a claustrophobic horror picture into a frightening, if not arguably overstated drama about spirituality.

The sole change that improves upon the original version features Merrin and Karras resting outside of Regan’s room, having just witnessed the shocking extent to which their enemy has overtaken the girl. Karras questions why this is happening to Regan of all people. Merrin offers his point of view, which Blatty has confirmed is the meaning of the picture: “I think the point is to make us despair, Damien—to see ourselves as animal, and ugly—to reject our own humanity—to reject the possibility that God could ever love us.” The suggestion is that Satan has chosen Regan not because she is vulnerable, but because those around her are vulnerable. The demon’s goal is to drive the family apart and antagonize Karras, while also inciting a re-match of sorts against Merrin, whom Satan has battled before. Regan’s imaginary friend, Captain Howdy, tells her lies about Chris’ friend Dennings to drive them apart; the demon attacks Karras where it hurts, with his mother. The real victim is not Regan, but those who must bear witness helplessly as the demon tears down the girl.

More exhaustive assessments have detailed the troubled production history of The Exorcist, namely Mark Kermode’s thorough book, which also goes to great lengths to praise the re-release for its submittal to Blatty’s overstated vision. But the spiritual message was effectively communicated upon the film’s initial release, despite the desire for some audiences to have a film’s meaning in black and white. In this case, the meaning’s colors are shown in the sudden contrast of demonic blue flesh that gives way to Karras’ face, his faith reestablished and spiritual victory over the demon complete when he sacrifices himself to bring to an end to its torment. Those who interpret the film as demonic fail to recognize Karras’ spiritual victory over evil in the climax, which in turn forces all audiences to confront their own beliefs about spirituality in the face of true evil. After all, it was the original version that had audiences throwing up in the aisles but then considering their spirituality afterward, whereas the extended version allows the viewer to decompress, losing much of the isolation and momentum that made the original so engaging.

How else but through the film’s profound spirituality—achieved via the combination of shocking visuals, the dismissal of other explanations (i.e. medical or psychiatric), and the terrifying reality of the horrors of evil—does one explain such extreme responses over the years? The Exorcist continues to affect audiences, transcending what it means to be “a horror film” through its unparalleled construction, and the balance of visceral imagery designating the resonant emotional and spiritual questions therein. Other filmmakers have attempted to out-do Friedkin’s work, but the horror genre almost never allows for the degree of insight or good intentions that is accomplished through such graphic content. The Exorcist realizes a unique stability between image and substance that audiences cannot disregard, and which has established the picture as an indisputable classic of its genre.

Bibliography:

Blatty, William Peter. The Exorcist . Buffalo: Harper & Row, 1971.

Kermode, Mark. The Exorcist (BFI Modern Classics). British Film Institute; 2nd Revised edition, 2008.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review