The Definitives

The Curse of the Cat People (1944)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

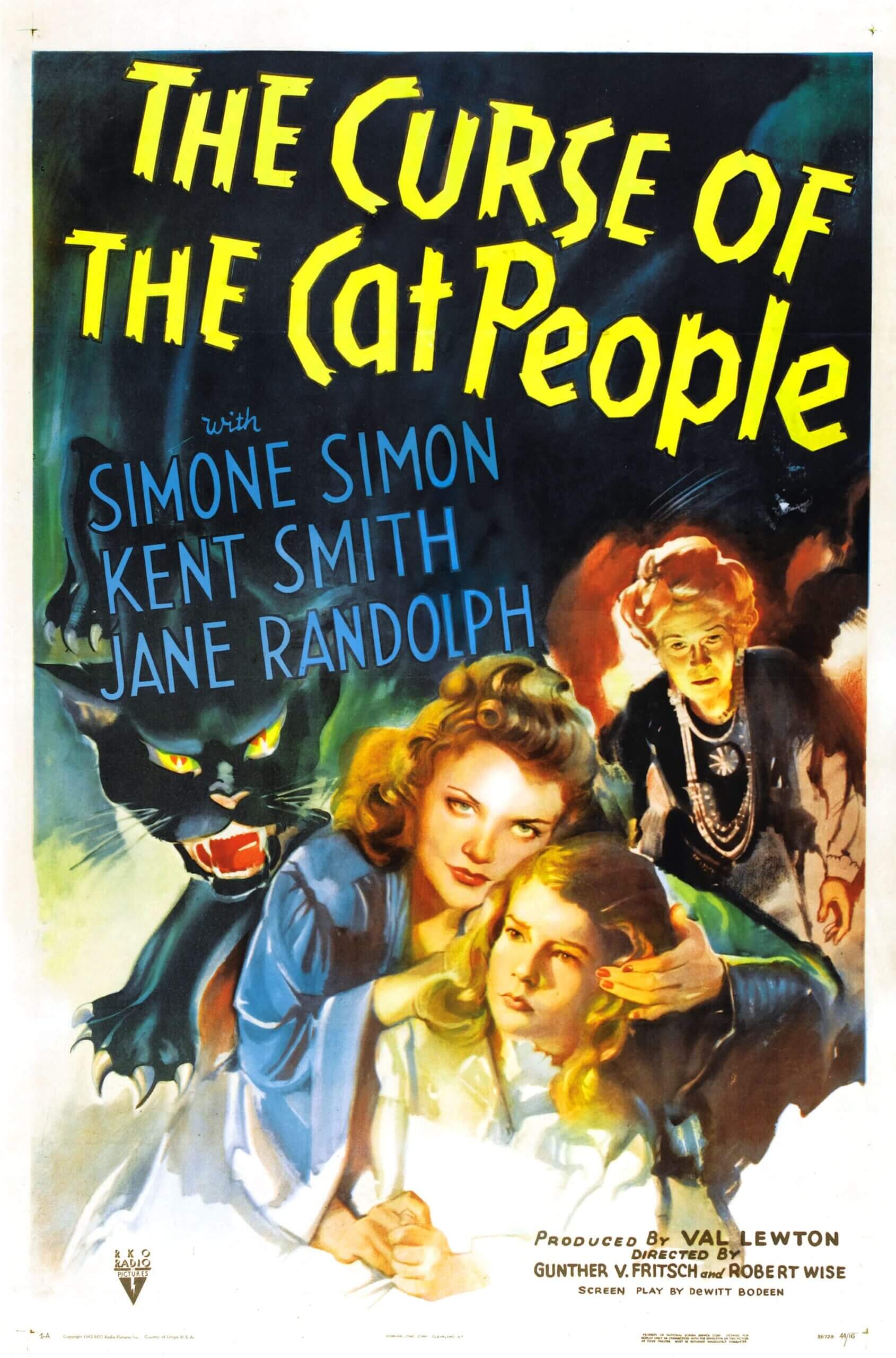

The Curse of the Cat People remains among the strangest Hollywood sequels ever made. Following Cat People, RKO’s 1942 horror masterwork of shadow and atmosphere that also helped delay the studio’s financial ruin, the sequel resolves to occupy another genre entirely. Most sequels, both then and today, duplicate what came before—the same characters dealing with similar situations, sometimes learning new lessons, but usually just being reminded of an identical message or warning all over again. Rare examples build on the mythology of their predecessor, using the source as a springboard to advance the characters and narrative of the original material. Even rarer still is something like The Curse of the Cat People, an unusual and poetic picture that seems to exist in an alternatively dreamlike world. It should come as no surprise that producer Val Lewton, an uncommon mind in the field of horror, should approach his only sequel in unconventional ways. Along with his writer from Cat People, DeWitt Bodeen, Lewton avoided another tale of human-animal transformations; despite the title, his film bows an early sample of today’s popular coming-of-age fantasy film, where the setting is the mind of a child, and the impossible comes to life through imagination.

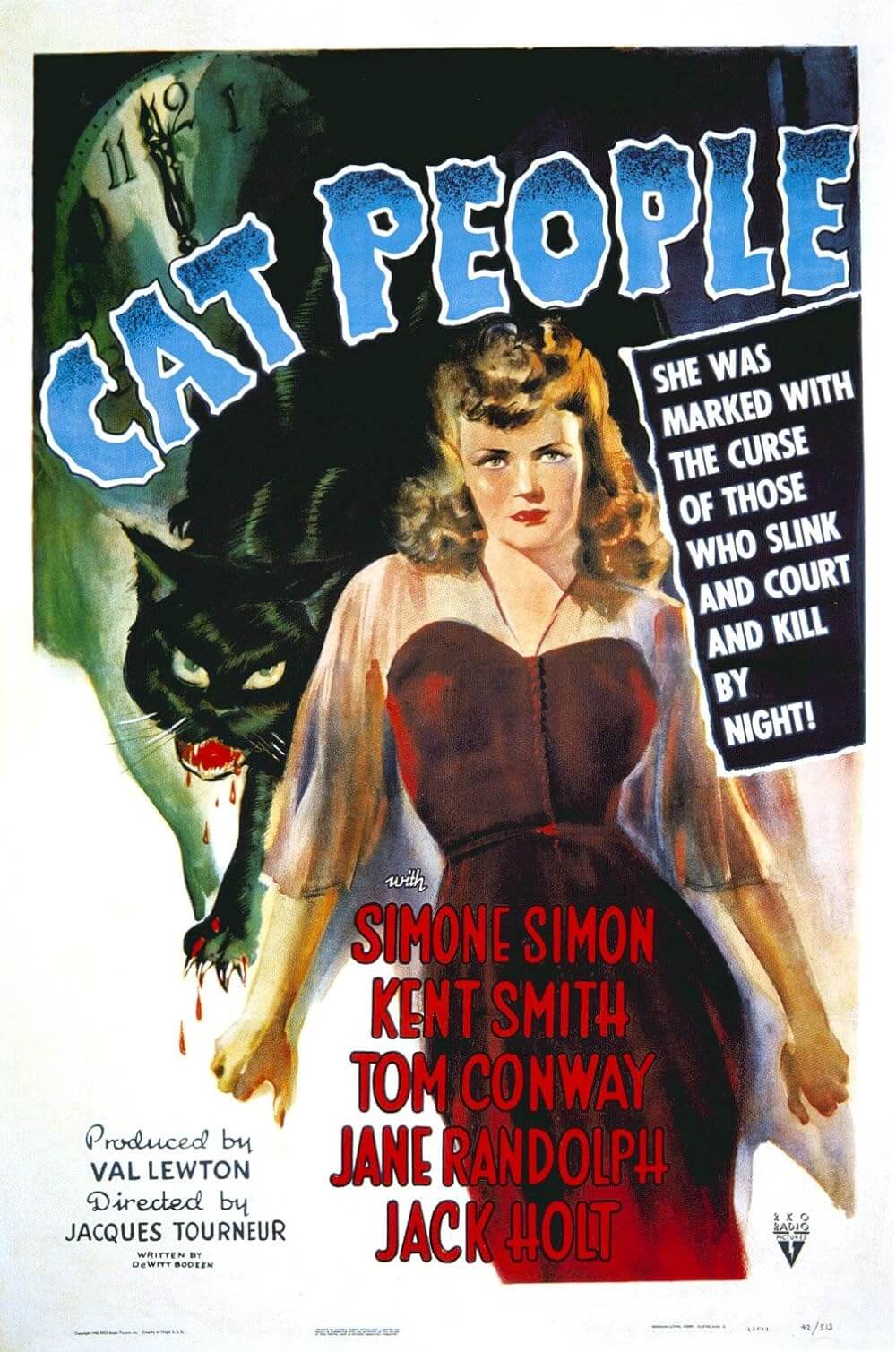

Cat People followed Irena (Simone Simon), an émigré from Eastern Europe who is plagued by sexual anxiety because, according to her people’s mythology, she will transform into a feline monster if she embraces her desires. Her husband, Oliver (Kent Smith), remains denied in the bedroom, and so he seeks consolation with his friend and coworker Alice (Jane Randolph). Fearing the worst and eventually unleashing her inner feline in a were-cat metamorphosis, Irena resolves to kill herself rather than embrace her animal side. After the film’s release and unexpected box-office success, Hollywood responded with a series of films borrowing from Lewton and Bodeen’s model (to call the subsequent films “inspired by” would be a stretch). Dozens of B-movie productions in the years to come involved a heroine fearing a unique curse that may transform her into a monster, some of them cross-breeding elements from Universal’s The Wolf Man (1941) with Cat People, and some clearly derived from Lewton’s production. In 1943, Columbia debuted Cry of the Werewolf, featuring starlet Nina Foch as a gypsy woman cursed with a form of lycanthropy. Universal’s The She-Wolf of London and The Cat Creeps, both unveiled in 1946, were obvious nods to Lewton’s work. Other, similar films offered women fearing vampire curses (The Bat’s Daughter, 1946) or even transforming into a gorilla (Jungle Woman, 1944), but each of them rely more on silly monster costumes and haunted house scares, as opposed to Lewton’s brand of shadowplay and theme.

RKO had the same idea and tasked Lewton’s maverick “B” horror unit to make a sequel. In late 1943, Lewton’s team was just finishing their work on their fifth production, The Ghost Ship, when RKO demanded a sequel to Cat People, hoping to repeat its commercial success. And much like before, the studio handed down their title to Lewton. Saddled with a name like “The Curse of the Cat People,” Lewton once again set out to create a film worthy of his talent. Despite the studio’s demands for a horror film they could market to audiences, Lewton controlled the picture’s narrative content. He carried over characters from the first film if only to service the new story, but their connections prove superficial, allowing the film to explore entirely new ideas, many of them drawn from Lewton’s own childhood experiences. His wife Ruth later remarked that, as a child, Lewton was “forced to retreat from reality into an insubstantial world of his own creation.” She added that he “never quite made it back to reality.” Lewton explores that very notion in The Curse of the Cat People—a film that shares much in common with more contemporary works by filmmakers who combine coming-of-age stories with dark tales of imagination, such as Hayao Miyazaki’s My Neighbor Totoro (1989) and Spirited Away (2001), Guillermo del Toro’s El laberinto del fauno (2006), or Spike Jonze’s Where the Wild Things Are (2009).

In typical Lewton fashion, he and Bodeen worked on a meticulous script, including detailed notes on directorial and aesthetic choices, though the producer received no writing credit. In this sense, the director on any Lewton production had their job spelled-out for them in advance. The studio gave Lewton director Gunther Von Fritsch, who had helmed a few documentary shorts, while Robert Wise (who had assembled Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons for RKO) was hired as the editor. The shoot commenced on August 26, 1943, with an 18-day filming schedule. Three weeks later, Fritsch had completed less than half of the script. As Fritsch was working on his first feature-length studio film, he labored over every shot. Lewton realized his director’s inexperience was setting the production behind. Wise later told author Lewton biographer Joel E. Siegel, “Val tried and tried to get Gunther to pick up the tempo, but it was his first job and he was just too nervous to move any faster. One Saturday morning, I got a call from Sid Rogell, who was then head of the B-unit. Rogell told me that I was to replace Gunther on Monday morning.” Wise was hired, albeit reluctantly, for his first ever credit behind the camera (he shares onscreen credit after Fritsch, though Wise is widely regarded as the primary directorial force on the production), the start of a prolific and influential career directing iconic films such as The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) and The Sound of Music (1965).

The sequel finds Oliver and Alice now happily married, having put the events of the first film behind them. But Oliver’s first wife remains an ever-present memory and presence beneath the surface life of their household. He still keeps photos of Irena and insists that her favorite painting—a child playing with ghoulish cats, from the portrait Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zuñiga by Francisco de Goya, but credited to Irena—stays hung on the wall. Having made a home in Tarrytown, New York, far outside of the city, Oliver and Alice now have a six-year-old daughter, Amy (Ann Carter). She’s an imaginative girl with few actual friends, and so she takes to dreaming up imaginary ones, much to her father’s frustration. Oliver worries that Amy is too much like Irena—capable of getting carried away by her beliefs (Oliver never believed Irena’s supernatural claims). He insists that Amy play with real children, not her imaginary friends. One day, when Amy is ditched by some girls her age, she finds herself under the loom of a spooky old house. From an open window, the voice of an old woman, Mrs. Farren (Julia Dean), calls out, inviting her closer. Amy enters the property, looking for the woman who remains in the shadows on the second floor. Amy sees a handkerchief with a ring attached thrown from the window, and she takes the ring. Just then, Mrs. Farren’s daughter, Barbara (Elizabeth Russell, no apparent relation to her character from the original), appears and gives the child a hateful scowl.

When Amy returns home with the ring, her family’s servant (calypso performer Sir Lancelot, a Lewton fixture) tells her the ring will grant her wishes. Amy wishes for a friend. That afternoon, she plays in the yard with her new imaginary companion. The low sun causes ominous shadows, and a fall breeze showers the yard with dead leaves—as if something magical had been conjured by Nature. Lewton’s sense of atmosphere never wanes, and the scene is both hopeful yet foreboding. Amy’s new friend visits her at night in the form of a spectral silhouette, watching over her as she sleeps, protecting her. Only after Amy finds a photograph of her father’s first wife, whose name she learns was “Irena,” does she begin to see Irena, as played by Simon. “I come from a place of great darkness… and deep peace,” Irena tells Amy. Much of The Curse of the Cat People exists in a similar state between reality and fantasy, between logical thoughts and the imaginings of its dreamy characters. It would be easy to dismiss Amy’s vision of Irena as psychological transference, except that Amy’s friend sings to her in French and speaks in strange, cryptic passages. “If you leave, I’ll follow you,” Amy tells Irena. “No one can follow me,” Irena replies with a touch of melancholy. Has Amy invented a tragic friend for herself, or has the troubled ghost of Irena returned? The question remains.

Amy and Irena’s relationship reflects that of Mrs. Farren and her daughter, in that both relationships subsist on uncertain measures of truth, apparition, and reverie. Amy visits the wobbly Mrs. Farren several times in the film, including the climactic scene, by entering a house that seems prone to delusion. It’s a place filled with old books and taxidermied animals—including a frightening cat, its mouth stuffed full with a half-eaten bird, a predatory image. (For the old house, Lewton’s production reused the exterior set from Welles’ The Magnificent Ambersons, still standing on the RKO lot, including the interior staircase also used in Cat People, though decorated and lit quite differently here.) Mrs. Farren claims Barbara is not her daughter, but a servant, and that her daughter died at the age of six. Barbara, meanwhile, insists that Mrs. Farren has forgotten her, a notion that surely stings the icy character, if indeed she is Mrs. Farren’s daughter at all. In the final scenes, Amy runs into the woods on Christmas Eve, looking for Irena, who has disappeared, and whom Oliver has forbidden Amy from seeing. She arrives at the Farren house and, in a panic, Mrs. Farren tries to hide the girl, fearing Barbara will harm her out of jealousy.

As Mrs. Farren falls dead on the staircase from the excitement, Barbara approaches. Frightened, Amy calls to her friend, and Irena appears to her, overlaid onto Barbara. Amy rushes to her friend and hugs her, actually wrapping her arms around Mrs. Farren’s dubious daughter. At the same time, Barbara’s hands, her fingers jagged and terrifying, prepare to constrict around Amy’s neck. We cannot help but question whether Barbara is an “impostor, liar, and cheat” as Mrs. Farren warned. But all at once, Barbara stops herself. She embraces Amy, perhaps because her life caring for her delusional and suspicious mother has left her devoid of loving human contact. “My friend, you’ve come back to me,” cries Amy, believing that Barbara is Irena. Meanwhile, Oliver and Alice have sent out a search party to look for Amy. When they find her, Oliver carries her home through the backyard, resolving to grant the child her imaginary fancy. He asks Amy if Irena is in the backyard now. “Yes,” says Amy. “I see her too,” Oliver says, never taking his eyes away from Amy. Though Oliver may not believe his daughter’s claims (just as he didn’t believe Irena’s), he cannot deny that it has kept her happy and safe. And in the final shot, Irena appears to the audience—and the audience alone—just before fading away.

In pagan times, long before people celebrated the Victorian-era ideal of Christmas, families told creepy fireside tales to commemorate the darkest days of the Winter Solstice, when the boundaries between the living and dead were thought to be at their thinnest. The Curse of the Cat People might be such a tale. Of course, Lewton’s production looks textured and ethereal, but it also takes on the appearance of a storybook—perhaps the sort of spooky tale that was once told on Christmas Eve. Art decorators Albert S. D’Agostino and Walter E. Keller, alongside set decorators Darrell Silvera and William Stevens, create a multifaceted backyard environment for Amy using a single set. Opening in the early autumn, a few leaves adorn the grassy yard floor, where Amy plays sad and alone. When she first meets her friend, the set grows dark, leaves begin to fall, and the trees create expressive shadows captured by cinematographer Nicholas Musuraca. The setting and narrative soon give way to winter. During the later Christmas scenes, the production’s stagey look uses fake snow and a shimmering icicle effect on the bare branches. Though the entire set-piece has been constructed on the studio lot, the filmmakers transform the space with each new scene, making the transitions between the seasons believable, and a fantastical looking component to the storybook world presented in the film.

Indeed, the film’s opening titles are adorned with macabre storybook pages; the title card appears with a frightening cat-headed flying creature like something out of Bosch. This introduction proves fitting for the story’s setting, just south of Sleepy Hollow, which remains haunted by Halloween lore. In one visit to Julia’s, Amy hears the old woman’s chilling account of Washinton Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” complete with a headless horseman and the sound of galloping hooves in Amy’s ear, brought to life by her overactive imagination. The film occupies the place in Amy’s mind that creates these fantasies and gives them some sensory reality. Later, as she runs through the winter storm on Christmas Eve to find Irena, she hears the clip-clopping of hooves on the road and imagines the Headless Horseman coming for her, but she soon realizes the sound was a passing automobile. Amy acknowledges that a portion of her illusions are tricks of her mind. Even so, the film never resolves with any certainty Amy’s belief in Irena, though plenty of evidence supports either interpretation.

In this uncertain setup, every dynamic has changed between the original film and the sequel. The film’s perspective is situated in the mind of a child rather than a fragile and sensitive woman. Oliver and Alice now have the intimacy of marriage instead of an unacknowledged coworker romance. Irena, whether she is real or merely an apparition in Amy’s mind, seems tender and sincere in place of insecure and unpredictable. The disconnect between Cat People and The Curse of the Cat People was no concern to RKO; they wanted a product that could be advertised and recognized as a sequel to their earlier hit. The title remained among the production’s few elements that eluded Lewton’s control. He originally appealed to the studio to change the title to “Amy and Her Friend” and, perhaps for the better, the studio turned down the idea. Regardless of the resulting film, RKO’s promotional department showered posters and lobby cards with imagery of panthers, fangs, claws, and a looming Simone Simon to compel fans of the original. One of the posters suggested Irena would slink “into the heart of a little girl who could not see the evil behind her smiling lips that could snarl, and feline fingers that could rip young flesh to shreds!”

Most critics and audiences remained confused by the title, misleading advertisements, and peripheral connections to the 1942 film; regardless, most praised the sequel, including some child psychologists and parent groups that applauded its representation of a child’s mind. Among the film’s champions, critic James Agee wrote a loving review in The Nation, citing a few of the film’s B-movie downfalls but praising its thoughtfulness: “When the picture ended and it was clear beyond further suspense that anyone who had come to see a story about curses and were-cats should have stayed away, they clearly did not feel sold out; for an hour they have been captivated by the poetry and danger of childhood, and they showed it in their thorough applause.” Agee later named it one of the best films of 1943, citing its exceptional and humane ability to tell its story through the eyes of a child. True enough, The Curse of the Cat People intelligently and sensitively occupies Amy’s psychological mindset, so much so that child psychology researchers at UCLA, the Los Angeles Council of Social Agencies, and famous sociologists used the film in their lectures to discuss the common unease that accompanies this developmental stage in a child. Lewton was sometimes asked to join the lecture and discussion, and instead of taking credit for the intricacies of the central performance, he gave credit to Carter, a popular child star in the 1940s who gave up her acting career after contracting polio.

Classic Hollywood productions rarely ever bothered to consider childhood a serious subject for motion pictures, and children seldom received center stage in Hollywood productions, short of being relegated to the doll-like Shirley Temple brand of cutesiness. And few films have ever captured the mind of a child so beautifully, existing in a state that never quite determines what reality is. The viewer remains uncertain as to whether Amy’s visions derive from Irena’s ghost watching over the daughter of her former husband, or if Amy has created Irena in her mind, possibly from half-understood stories about her father’s first wife (similar to Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Unseen Playmate, quoted in the film). The film also draws significant connections between adults and children in the film, suggesting not only a biographical nod to its author, Lewton, but also the innate reality that somewhere buried within every adult lingers their childlike self. Note the associations between Amy and Oliver. Just as any child feels engrossed by their play, Oliver preoccupies himself by playing cards with Alice, building model ships, daydreaming, and even playing tiddlywinks during Amy’s birthday party. More than one Lewton biographer has suggested that if Amy represents Lewton’s childhood dependence on fantasy and fear of the dark, then Oliver reflects Lewton’s boyish obsession with his hobbies, imagination, and work. The association better explains why Oliver seems like a dope, or somewhat immature and disassociated with his adult life, as if he’s going through the motions of how an adult is supposed to behave—a characteristic that certainly defines him in Cat People.

Often cited as Lewton’s most personal film, some even calling it his best, The Curse of the Cat People remains unclassifiable and beguiling, yet supremely human in its understanding of and sympathy for the inner workings of a child’s mind. Regardless of how RKO chose to promote the film as a sequel and bloody horror film, it altogether eschews the horror elements of its predecessor and resolves to exist in its own world, just as many of its characters do. The aforementioned childhood fantasies by Miyazaki, del Toro, Jonze, and countless unmentioned others, each occupy the headspace of a child whose trauma, emotional isolation, or simply awkwardness about growing up has been accompanied by the fantastical, allowing interpretations to range from a psychological coping mechanism to the phantasmic. Though Lewton has long been considered a progenitor of horror, The Curse of the Cat People demonstrates that, much like Amy or Oliver, or even this film’s predecessor, his realm belongs to the unconscious and introvertive. Confusingly titled though it remains (“cat people” are mentioned just once), the film presents an elegiac fantasy that never entirely resolves its questions about the real and the imagined, filling the picture with possibility, mystery, and enchantment.

Bibliography:

Bansak, Edmund G. Fearing the Dark: The Val Lewton Career. McFarland, 1995.

Hantke, Steffen, editor. Horror Film: Creating and Marketing Fear. University Press of Mississippi, 2004.

Jewell, Richard B. The Golden Age of Cinema: Hollywood 1925-1945. Blackwell Publishing, 2007.

Newman, Kim. Cat People. 2nd Ed. British Film Insititute, 2013.

Siegel, Joel E. Val Lewton: The Reality of Terror. Secker and Warburg, 1972.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review