The Definitives

The Crying Game (1992)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

“Scorpion wants to cross a river, but he can’t swim. Goes to the frog, who can, and asks for a ride. Frog says, ‘If I give you a ride on my back, you’ll go and sting me.’ Scorpion replies, ‘It would not be in my interest to sting you since as I’ll be on your back we both would drown.’ Frog thinks about this logic for a while and accepts the deal. Takes the scorpion on his back. Braves the waters. Halfway over feels a burning spear in his side and realizes the scorpion has stung him after all. And as they both sink beneath the waves the frog cries out, ‘Why did you sting me, Mr. Scorpion, for now we both will drown?’ Scorpion replies, ‘I can’t help it, it’s in my nature.’”

Filmmaker and novelist Neil Jordan’s The Crying Game contains a narrative daring whose complexity tests its audience through a discerning investigation of human nature. With extraordinary understanding through exigent circumstances, Jordan’s structure promotes human empathy and a redemptive sense of tolerance, destroying narrow-minded notions of sexuality, race, and politics for a greater awareness of human nature. Perceptions of the film have often suggested it hinges on a mid-film narrative shift comparable to those in Hitchcock’s Vertigo and Psycho, whereas only with repeated viewings does Jordan’s bold, nonconformist writing reveal its many rewards beyond the twist. As unlikely a love story as ever told, in Jordan’s seductive tale we root for an IRA terrorist and transgender woman to fall in love. But even after one knows the much-discussed secret, that the central female character is, in fact, a man, a predominant and hypnotic mystery encircles the lovers’ outcome, one that compels an audience to return to these characters again and again.

Jordan opens his film at a Belfast carnival, where British soldier Jody (Forest Whitaker) is lured away by an Irish woman, Jude (Miranda Richardson), and kidnapped by the IRA. Held hostage as the IRA negotiates for an exchange of prisoners with the RUC, Jody makes friends with his captor, Fergus (Stephen Rea), who shows concern for some decency in Jody’s treatment. As their brief friendship grows, the two debate about cricket, share stories and laughs, and Jody shows Fergus a photo of his gorgeous wife, Dil (Jay Davison), and asks that Fergus look out for her should he be executed. Fergus tells Jody not to think of such things, even though he knows the RUC is not likely to concede to their demands. But Jody does not blame Fergus should he have to kill him; it’s in his nature. Fergus wants to know what that means, and Jody recounts “The Scorpion and the Frog” fable, which saddens Fergus as a reflection of his choices. When their deadline comes to pass, Fergus’ superior, Maguire (Adrian Dunbar), orders him to lead Jody into the woods; as he does, the prisoner begins to run and Fergus cannot shoot him in the back. Fergus finds himself running with Jody to escape. All at once, Jody reaches a road and is struck by an oncoming RUC truck. Troops raid the IRA hideout. Fergus escapes into the forest and finds his way to a friend who will set him up in London. “Need to lose myself awhile,” Fergus explains.

In London, Fergus finds a job as a construction worker; the site overlooks a cricket game and Fergus thinks of Jody, his friend. Not forgetting his promise, Fergus looks Dil up and finds her working at a salon, where he gets his hair cut. She supposes he’s Scottish and they talk briefly. Afterward, he follows her to the Metro, a nearby nightclub where the local bartender, Col (Jim Broadbent), acts as the go-between for Dil, who realizes she has been followed and loves the attention, and Jimmy, the false name Fergus has adopted. Another suitor, the pushy Dave (Ralph Brown), bursts in and carts Dil away as Fergus watches without intervening. But the next night, Fergus returns to the Metro and protects her from Dave, leading to romance between them. Fergus asks her about her former man, Jody, but she refuses to talk much about him. Their romance grows, but when they finally set down to make love, to his horror Fergus discovers that Dil is a transgender woman. He impulsively lashes out on Dil and leaves. After coming to his senses, he apologies, and soon their relationship is healed, continuing on an undefined basis, without sexuality, but with evident love.

In London, Fergus finds a job as a construction worker; the site overlooks a cricket game and Fergus thinks of Jody, his friend. Not forgetting his promise, Fergus looks Dil up and finds her working at a salon, where he gets his hair cut. She supposes he’s Scottish and they talk briefly. Afterward, he follows her to the Metro, a nearby nightclub where the local bartender, Col (Jim Broadbent), acts as the go-between for Dil, who realizes she has been followed and loves the attention, and Jimmy, the false name Fergus has adopted. Another suitor, the pushy Dave (Ralph Brown), bursts in and carts Dil away as Fergus watches without intervening. But the next night, Fergus returns to the Metro and protects her from Dave, leading to romance between them. Fergus asks her about her former man, Jody, but she refuses to talk much about him. Their romance grows, but when they finally set down to make love, to his horror Fergus discovers that Dil is a transgender woman. He impulsively lashes out on Dil and leaves. After coming to his senses, he apologies, and soon their relationship is healed, continuing on an undefined basis, without sexuality, but with evident love.

By this time, Jude and Maguire have found Fergus in hiding. They inform Fergus that the IRA has court-martialed him for abandoning the cause and failing in his mission to execute Jody, and they order him to carry out a suicide mission to assassinate a British judge. In exchange, they agree not to involve Dil, who they have spied him with but whose significant identity remains unknown. To protect Dil, Fergus cuts her hair and dresses her in Jody’s cricket garb, telling her to stay in a hotel room. Beside herself, Dil gets drunk and leaves to meet Fergus at her apartment. Here Fergus confesses that he knew Jody and caused his death. As Fergus sleeps, Dil sobers up and ties Fergus to the bed at gunpoint, causing him to miss the scheduled assassination. Maguire panics when Fergus doesn’t show and is killed trying to complete the hit himself. Out for revenge, Jude arrives at Dil’s to confront Fergus, but she finds Dil there waiting. Dil fires on Jude, realizing she seduced her Jody, and then turns the gun on herself, but Fergus stops her. He sends her off to the Metro and prepares to take the blame for Jude’s murder. As the song over the end credits suggests, Dil stands by her man and visits Fergus in prison during the final scene, where he explains his sacrificial behavior by stating it was in his nature, and then tells her the story of “The Scorpion and the Frog”.

Conceived long before he first proposed to make it, the idea, originally called The Soldier’s Wife, was first suggested by Jordan to Channel 4 in May 1982 following the release of Jordan’s first directorial effort, Angel, an independent hit starring Stephen Rea as a saxophonist who witnesses an IRA murder. For The Soldier’s Wife, Jordan was inspired by Frank O’Connor’s short story Guests Of The Nation and Brendan Behan’s play The Hostage, both of which concern relationships between hostage and kidnapper, and both with characters in the IRA. More than those works, Jordan thought his concept too close to Bernard MacLaverty’s novel Cal, and so opted to set aside the project. In the decade between his initial proposal and the completed film that reached theaters in 1992, Jordan would make a name for himself with five feature films and a short novel. The success of personal projects such as Mona Lisa (1986) gathered the attention of Hollywood, where Jordan was limited to drivel such as the supernatural comedy High Spirits (1988) or the unfortunate remake We’re No Angels (1989).

After his spell in Hollywood, Jordan returned to Ireland to reclaim his roots and explore a more personal project. Along with producer Stephen Woolley, who had developed a number of Jordan’s works since The Company of Wolves (1984), the two searched for financing and found investors unwilling to take a risk on Jordan’s script so charged with racial, sexual, and political subject matter—often one such trait was enough, but all three was too much for prospective investors. In time, several obscure British, European, and Japanese investors supplied portions of the budget, leaving Channel 4 to secure the remainder of the $5 million price tag. Still, Woolley was forced to borrow funds from the box-office of his own movie house, The Scala Cinema, and use personal credit cards to complete the film on time, before Christmas of 1991. For his leading man, Jordan returned to Stephen Rea, whose ongoing career-long collaborations compare to those of Scorsese-DeNiro or Kurosawa-Mifune. The actor’s inclusion given the film’s IRA themes brought questions into Rea’s politics, being a Protestant-turned-Catholic married to, at the time, Dolores Price, a former volunteer of the Provisional IRA. Early accusations that the eventual film would be pro-IRA spread. Moreover, the press balked when they learned an American (Whitaker) would be playing a Brit, and a Brit (Richardson) would be playing an Irishwoman. National actors unions believed a Brit should play a Brit and an Irishwoman should play an Irishwoman.

After his spell in Hollywood, Jordan returned to Ireland to reclaim his roots and explore a more personal project. Along with producer Stephen Woolley, who had developed a number of Jordan’s works since The Company of Wolves (1984), the two searched for financing and found investors unwilling to take a risk on Jordan’s script so charged with racial, sexual, and political subject matter—often one such trait was enough, but all three was too much for prospective investors. In time, several obscure British, European, and Japanese investors supplied portions of the budget, leaving Channel 4 to secure the remainder of the $5 million price tag. Still, Woolley was forced to borrow funds from the box-office of his own movie house, The Scala Cinema, and use personal credit cards to complete the film on time, before Christmas of 1991. For his leading man, Jordan returned to Stephen Rea, whose ongoing career-long collaborations compare to those of Scorsese-DeNiro or Kurosawa-Mifune. The actor’s inclusion given the film’s IRA themes brought questions into Rea’s politics, being a Protestant-turned-Catholic married to, at the time, Dolores Price, a former volunteer of the Provisional IRA. Early accusations that the eventual film would be pro-IRA spread. Moreover, the press balked when they learned an American (Whitaker) would be playing a Brit, and a Brit (Richardson) would be playing an Irishwoman. National actors unions believed a Brit should play a Brit and an Irishwoman should play an Irishwoman.

Even though Jordan somehow completed principal photography on schedule for his nightmare production, wrought by budgetary constraints, Channel 4 demanded a different ending than the one Jordan had filmed, which featured Dil visiting Fergus in prison and giving him a copy of Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams. Jordan wrote an alternate “happy” ending where Dil and Fergus meet again on a white Christmas, but ultimately selected the conclusion in the final film, where in prison Fergus recounts Jody’s tale of “The Scorpion and the Frog” for Dil—an ending hopeful but ambiguous toward the future of Fergus and Dil’s relationship. Jordan’s aversions to genre stereotypes and predictability aside, when the film was submitted to the Cannes Film Festival for competition, the jury denied its entry, claiming it was “a bit too Anglo-Saxon” for the festival. And yet, UK critics, influenced by a rash of IRA attacks on London during the time of The Crying Game’s release on October 30, no doubt found sympathy for an IRA protagonist difficult, resulting in the largely mixed reviews. The critics agreed to an embargo on revealing the film’s twist, but the release, which earned a pithy $2 million in receipts, contained an air of “predestined failure”, given how press and marketing campaigns were virtually nonexistent. Moreover, a miasma hovered over its release, being the last bastard child of Woolley’s ill-reputed studio Palace Pictures, which had gone bankrupt a few months earlier.

The ultimate irony remains how the U.S. market celebrated The Crying Game, thanks largely to the support of Miramax chief Bob Weinstein who, despite having passed on producing Jordan’s script, called the finished film “one of the greatest movies [he’s] ever seen.” Miramax purchased U.S. distribution rights for around $1 million and conceived an ingenious marketing campaign to promote its release. Their clever tactic suggested buzz in the states before there was any, using the line “The movie that everyone’s talking about, but no one is giving away its secrets.” Filled with insinuations and hints, the campaign of words like “secret” and “game” encouraged audiences to participate in keeping quiet about the twist, and indeed they did. U.S. critics especially tested themselves by writing elaborate reviews that talked all about the film but rarely hinted that Dil was a man. The buzz brought about surprise commercial success in the U.S., earning the film $68 million and making it 1992’s most profitable release by percentage. Even during the height of its popularity, audiences and critics alike kept the film’s secrets for the sake of fellow viewers; only when the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences nominated Jaye Davidson for Best Supporting Actor was the secret unintentionally revealed.

Clever though Miramax’s advertising strategy may have been, it created an unfortunate myth that The Crying Game’s dramatic reach is contained within the twist that Dil is a man. Such an oversimplification does not account for Jordan’s complex narrative structure, his confronting political implications, and his unique mixture of genres. Consider how the first half-hour of the film inhabits a political kidnapping thriller pretext, complete with a sympathetic kidnapper who is forced to choose basic human compassion over his cause; entire films have used this setup, but this is only the first act to Jordan’s. When that strain builds to an unexpected end as Jody dies, the story progresses into something more atmospheric, what at first takes the appearance of a redeeming love story, another genre type that seems very familiar. But again, Jordan defies genre expectations when his twist reveals that Fergus has fallen in love with a man, and furthermore entered into a love triangle in which the third party is dead. Jody consumes both Fergus and Dil; he brings them together and drives their individual longings. And, seeing beyond political ties and gender assignments, Fergus becomes Dil’s protector, even in defiance of the IRA.

Clever though Miramax’s advertising strategy may have been, it created an unfortunate myth that The Crying Game’s dramatic reach is contained within the twist that Dil is a man. Such an oversimplification does not account for Jordan’s complex narrative structure, his confronting political implications, and his unique mixture of genres. Consider how the first half-hour of the film inhabits a political kidnapping thriller pretext, complete with a sympathetic kidnapper who is forced to choose basic human compassion over his cause; entire films have used this setup, but this is only the first act to Jordan’s. When that strain builds to an unexpected end as Jody dies, the story progresses into something more atmospheric, what at first takes the appearance of a redeeming love story, another genre type that seems very familiar. But again, Jordan defies genre expectations when his twist reveals that Fergus has fallen in love with a man, and furthermore entered into a love triangle in which the third party is dead. Jody consumes both Fergus and Dil; he brings them together and drives their individual longings. And, seeing beyond political ties and gender assignments, Fergus becomes Dil’s protector, even in defiance of the IRA.

Love triangle motifs recur again and again in Jordan’s works, in most cases when a naïve man grows interested, if not obsessed with a woman already devoted to another. Such is the case with Mona Lisa, where Bob Hoskins falls for a high-class prostitute searching for her lesbian lover; also in Interview with the Vampire, where three central vampires form a family in which each member desires something and someone else. In the realm of Jordan’s characters with unresolved issues, Fergus is most explicit, in that his persistent love for Jody consumes his pursuit of Dil. Haunted by dreams of Jody, Fergus soon meets his former captive’s “wife”, a mysterious club woman for whom Fergus becomes a guardian. Still, images of Jody endure in Fergus’ head, even after the romance between Fergus and Dil fires up. During Dil’s offering of fellatio, Fergus drifts off into a daydream about Jody dressed white in cricket attire, delivering a pitch; Fergus’ eyes drift around the room and regard photos of Jody as he climaxes. In a way, Fergus loves a dead man, a love that materializes as Dil transforms into Jody. Almost as if willed by Fergus’ affections and persistent questions about Jody, Dil reveals she is a man. Later, when Jude returns to force Fergus back into the IRA, Fergus disguises Dil and dresses her in Jody’s cricket uniform. Dil ostensibly becomes Jody when, in that uniform, she carries out Jody’s revenge on Jude.

Fergus’ all-consuming remorse over Jody’s death becomes even more evident on the second screening, when hints to the twist, which both Fergus and the viewer initially overlook, reveal themselves. Fergus pushes forward in his quest for Dil, already convinced of her allure by Jody’s testimonies, and remains blind to all other details. When the viewer watches the film again with the knowledge of what happens, moments of Why didn’t I see this before? emerge, such as Dil’s presence in the club scene or Davidson’s somewhat masculine hands and neck. But the first time around, we are just as unsuspicious and swept up in Dil’s allure as Fergus. We also overlook Jody’s flirtatious, manipulative dialogue with Fergus—the one terrorist kind enough to offer tea—which implies a deeper purpose to the film. No one can watch The Crying Game a second time and deny the pull between Fergus and Jody during their time together. “You’re the handsome one with the killer smile and the baby face,” Jody notes to his captor, pleading with him to remove his canvas hood. Fergus responds, “Am I?” Jody smiles under his hood, “Yeah, and the brown eyes… You’re the handsome one.” Fergus feeds Jody and the captive says, “Thank you, handsome.” Now playing along, Fergus admits “My pleasure.” Later on, after Fergus must remove Jody’s penis from his pants so that he may urinate, Fergus quips again, “The pleasure was all mine.” Jocular laughs though these may be, once the story progresses, it become apparent there was something more between them.

Jordan’s spare writing leaves audiences open to interpret interior emotions based on what actors have drafted on their faces with unprecedented understatement. His characters behave and think internally, so determining the motivation behind every turn and passage requires projection. Indeed, The Crying Game contains two of the most reserved performances, the most apparent by Davidson, and the other by Rea. Casting Dil became a major concern for Jordan during production, as he was told by friend Stanley Kubrick that finding the right individual for the part, man or woman, was probably impossible. A casting director found Davidson in a club not unlike the Metro. Davidson was reluctant and had never considered acting, but through the long casting process was chosen for the role because his brusque personality evoked just the sort of sharp-but-mystifying confidence that Dil required. Furthermore, Jordan never allows Davidson to be portrayed as an absurdist caricature, as characters in cross-dressing films such as Some Like it Hot or Tootsie often are. Davidson may be dark humored, witty and ironic, but never farcical. His inscrutability is convincing enough so the character’s gender shifts (from feminine to masculine then back to feminine) are each persuasive, layering the character’s many dimensions. Whether or not it was brilliant acting or simply fortunate casting, the effect in the film is undeniable.

Jordan’s spare writing leaves audiences open to interpret interior emotions based on what actors have drafted on their faces with unprecedented understatement. His characters behave and think internally, so determining the motivation behind every turn and passage requires projection. Indeed, The Crying Game contains two of the most reserved performances, the most apparent by Davidson, and the other by Rea. Casting Dil became a major concern for Jordan during production, as he was told by friend Stanley Kubrick that finding the right individual for the part, man or woman, was probably impossible. A casting director found Davidson in a club not unlike the Metro. Davidson was reluctant and had never considered acting, but through the long casting process was chosen for the role because his brusque personality evoked just the sort of sharp-but-mystifying confidence that Dil required. Furthermore, Jordan never allows Davidson to be portrayed as an absurdist caricature, as characters in cross-dressing films such as Some Like it Hot or Tootsie often are. Davidson may be dark humored, witty and ironic, but never farcical. His inscrutability is convincing enough so the character’s gender shifts (from feminine to masculine then back to feminine) are each persuasive, layering the character’s many dimensions. Whether or not it was brilliant acting or simply fortunate casting, the effect in the film is undeniable.

Rea’s performance demands to be heralded as well, even if credit should also be given to simply correct casting. Jordan had repeatedly used Rea for his natural presence, having cast him in almost every film since his earliest effort on Angel. The actor’s enduring persona carries an austerity filled with conflicting emotions that, despite Fergus’ status as an IRA kidnapper, propose innocence. At the same time gentle and violent, understanding yet inexperienced, searching but stoic, Rea’s presence harbors an indefinable element on par with Jean Gabin or Humphrey Bogart. Without a doubt, Rea has a Bogart look and appeal, as he is not an attractive actor by traditional standards but has an oddly charismatic quality about him. Rea looks as though a weight resides on his shoulders, a slump in his posture, and a burden on his eyes. He embodies the tortured role of Fergus with a great deal of heroism, but also vulnerability whose very internalization and understanding confronts the prototypical view of macho Irishmen.

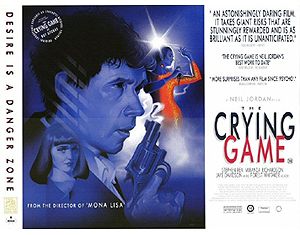

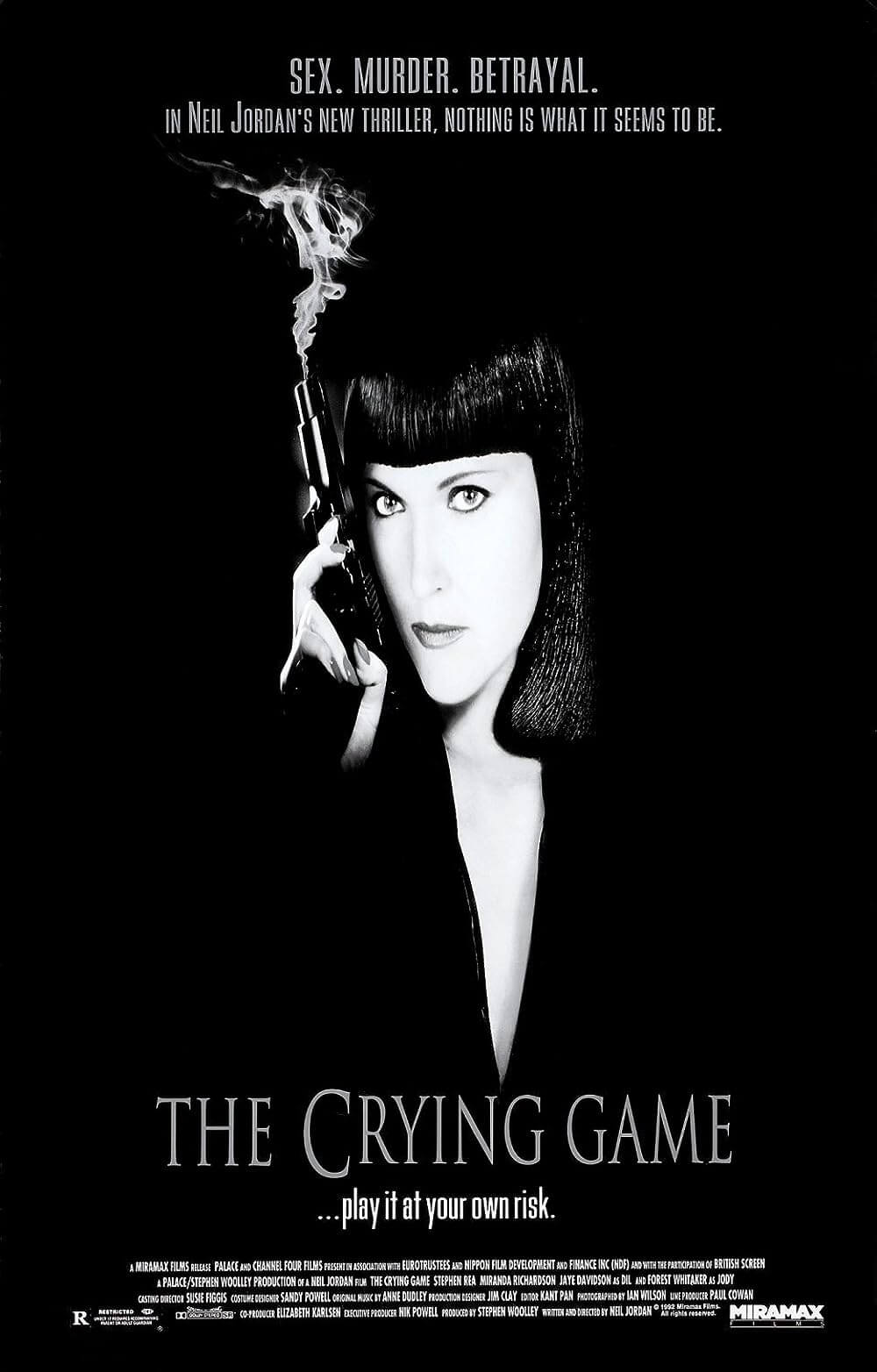

Though Richardson’s presence was originally a concern for the production’s Irish authenticity, her performance convinced even the most vocal detractors. It was ironic that Miramax chose her image on the poster, given the character’s sideline role next to the romance between Fergus and Dil. But Jude completes the second love triangle in Jordan’s film, her pursuit of Fergus in vain once he leaves the IRA and finds Dil. From a feminist outlook, Jude may seem empowered by her station as a protean footsoldier willing to change her appearance and sacrifice her sexuality for her cause, whereas another interpretation recognizes that the men in the room still demand that she make the tea and sandwiches. Instead, her representation as an individual or a woman is less crucial than how she is viewed from the perspectives of Fergus, Jody, and most significantly Dil. Jude embodies female sexuality, using “those tits and that ass” to seduce Jody and draw Fergus’ attentions. For Jody and Fergus, she is a woman who cannot possibly understand their tastes. “She’s not my type,” Jody confesses, despite being an attractive female subject whose very image has its powers. Dil’s perception places Jude as the ultimate threat, her uniform sexual identity and gun-carrying soldier status having robbed her of one lover, and threatens to steal another. Jordan’s depiction of Jude does not signify his stance on women, rather constructs a villain who by her feminine nature is a threat to his central characters.

Sexual politics were overlooked in favor of national politics when it comes to Jude; however, The Crying Game’s harshest critics accused Jordan of demonizing women (instead of one woman), which also led to accusations of anti-IRA sentiments, as though Jude represented the entire Irish Republican Army. Then again, Fergus’ sentimental humanity was viewed as propaganda for the IRA, particularly by critics in Northern Ireland who saw Jordan as merely a southern Irish filmmaker. But Jordan’s view of the IRA, illustrated more directly in his 1996 biopic Michael Collins, finds hope in a cause long since skewed by years of violence. “The IRA has done terrible things,” Jordan said in an interview for the film. “But what’s important about the way the film approaches that reality is that they’ve become people they didn’t want to be. That doesn’t mean the cause is wrong.” Critics who attempt to point fingers at pro- and anti-IRA, pro- and anti-woman, or pro- and anti-transgender messages in the film have already forgotten the lesson learned in “The Scorpion and the Frog”, that people will remain true to their natures.

This does not mean that an IRA operative is nothing more than their political status, or that a woman is nothing more than a woman, or that sexuality is reduced to all the associations thereof. Regardless of influence, including politics and gender and sexuality, individuals will remain true to their natures. The Crying Game searches for its characters’ natures with a yearning that at once unveils yet retains mystery, not only in terms of sexual and political identity, but in the capacity for understanding and compassion. This is not a film about judgment, but about people required to do something they do not want to do, and the tragedy behind forcing someone to change their nature. Thus, it is about acceptance and tolerance and, for Fergus, sexuality, or sexual polarity, which are blind and all-consuming assignments. Jordan’s film explores the gray areas of those assignments and finds hope for such black and white divisions.

Bibliography:

Giles, Jane. The Crying Game. London: British Film Institute, 1997.

Rockett, Emer; Rockett, Kevin. Neil Jordan: Exploring Boundaries. Dublin, Ireland: Liffey Press, 2003.

Zucker, Carole. The Cinema of Neil Jordan: Dark Carnival. New York: Wallflower Press, 2008.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review