The Definitives

The Blue Angel (1930)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

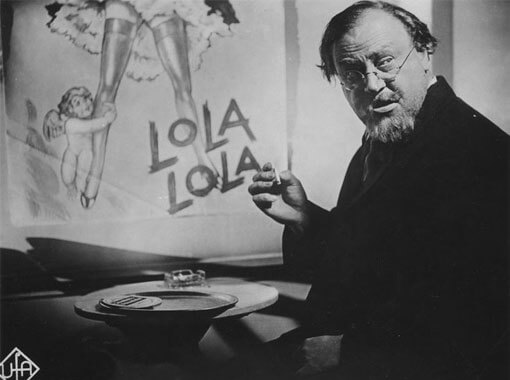

Seated on a beer barrel, the scantily clad Lola Lola appears in black regalia, a top hat tilted to one side, her arms bare, her skirt dangling from her upper thighs as she leans back slightly, holding a knee with both hands to reveal her exposed garter straps and show her stockinged legs. Around her is a grotesque assemblage of nautical and cherub-themed decorations, layers of drapes, and overweight singers. All eyes are on Lola Lola as she sings a lusty tune, “Falling in Love Again (Can’t Help It),” in her low, smoky voice to an enrapt crowd of both men and women. An iconic image from the German film The Blue Angel (Der Blaue Engel, 1930), this vision of Marlene Dietrich, in her first collaboration with director Joseph von Sternberg, was repeated and revised throughout her career. The Blue Angel would feature Dietrich as she was in life, a performer whose sexuality was wielded with equal measures of confidence and mystery, and her persistent unknowability. From this film onward, questions remained, from what drives her heart to how, exactly, to define her sexual identity. Such questions shaped Dietrich’s uncommon, transgressive, and bewitching presence onscreen. Though she had appeared in films before, The Blue Angel advanced Dietrich into the consciousness of German audiences and, soon, the world forevermore. Beyond its consequence on its director and star, the film remains an artfully composed tale about a pitiable man of power brought to his knees by untamable forces, both Lola Lola and the crippling masochistic desire within himself.

Two conflicting narratives have sought to encapsulate the relationship between director Joseph von Sternberg and the screen presence of Marlene Dietrich, largely in an attempt to issue credit for how Dietrich’s screen persona was achieved. Early film historians and biographers devoted to the auteur theory argued that Sternberg served as Svengali over his star, controlling her appearance, selecting her wardrobe, and instructing her every movement, while he also articulated every point of light that illuminated her face, thus creating bold shadows around her eyelids and cheekbones. In essence, he single-handedly created the iconic image of Dietrich. Many modern writers have sought to change the narrative by exposing how Dietrich remained in control of her image throughout her career after six years and seven films alongside Sternberg. She had a vast understanding of her own presence and allure outside of heteronormative circles. She used her appearance to draw gazes inward while also retaining a unique outward gaze to confront and bond with the viewer, accounting for the indelible fascination that followed her. Sternberg, then, simply photographed a legend in the making who continued long after their alliance. Both narratives about Sternberg and Dietrich have their merits. Still, the reality, of course, is much more complicated, with hints of truth drawn from both tales—the master director, a European artist whose control was absolute, and the self-made feminist and queer icon who defied traditional representations of sexuality to become something unequaled.

The Blue Angel was not Germany’s first sound film, nor its most expensive production, but it was the country’s most admired release yet from the Weimar Republic’s premier motion picture studio, UFA (Universum Film Aktiengesellschaft). Producer Erich Pommer served as the head of UFA, producing such films as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler (1922), Die Nibelungen (1924), Faust (1926), and Metropolis (1927). He wanted an American to direct his next project—first the story of the Russian icon Rasputin, but then later an adaptation of the Heinrich Mann novel Professor Unrat—and he offered the job to Ernst Lubitsch. Lubitsch had already emigrated and established himself in Hollywood, and moreover, he was too expensive; Sternberg was not. The proposed film would star Emil Jannings, then hailed as the world’s finest film actor. Sternberg had already directed Jannings into the performer’s first Academy Award for Best Actor on The Last Command (1928). Mann’s novel followed a German professor, nicknamed “Unrat” or filth by his students, reduced to humiliation, crippling jealousy, self-degradation, and ruin over his love for and obsession with a cabaret singer, Lola Lola. Jannings would play Professor Rath in the film, now retitled Der blaue Engel, the title’s blaue a double-meaning for drunk—suggesting that Lola is drunk with love and lovemaking. As the singer refrains in “Falling in Love Again (Can’t Help It),” the iconic song that would follow Marlene Dietrich throughout the rest of her career: “Men cluster to me/Like moths around a flame/And if their wings burn/I know I’m not to blame.” From this role onward, Dietrich would be seen as an object of romantic longing; however, that desire would often bear a consequence of tragic fate.

The Blue Angel was not Germany’s first sound film, nor its most expensive production, but it was the country’s most admired release yet from the Weimar Republic’s premier motion picture studio, UFA (Universum Film Aktiengesellschaft). Producer Erich Pommer served as the head of UFA, producing such films as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler (1922), Die Nibelungen (1924), Faust (1926), and Metropolis (1927). He wanted an American to direct his next project—first the story of the Russian icon Rasputin, but then later an adaptation of the Heinrich Mann novel Professor Unrat—and he offered the job to Ernst Lubitsch. Lubitsch had already emigrated and established himself in Hollywood, and moreover, he was too expensive; Sternberg was not. The proposed film would star Emil Jannings, then hailed as the world’s finest film actor. Sternberg had already directed Jannings into the performer’s first Academy Award for Best Actor on The Last Command (1928). Mann’s novel followed a German professor, nicknamed “Unrat” or filth by his students, reduced to humiliation, crippling jealousy, self-degradation, and ruin over his love for and obsession with a cabaret singer, Lola Lola. Jannings would play Professor Rath in the film, now retitled Der blaue Engel, the title’s blaue a double-meaning for drunk—suggesting that Lola is drunk with love and lovemaking. As the singer refrains in “Falling in Love Again (Can’t Help It),” the iconic song that would follow Marlene Dietrich throughout the rest of her career: “Men cluster to me/Like moths around a flame/And if their wings burn/I know I’m not to blame.” From this role onward, Dietrich would be seen as an object of romantic longing; however, that desire would often bear a consequence of tragic fate.

Joseph von Sternberg was born Jonas Sternberg in 1894 to a Jewish family whose poverty-ridden home was within earshot of Prater, Vienna’s massive carnival of rides, barrel organs, freak shows, and secret rendezvous. The two dynamic worlds, Sternberg’s unhappy childhood in a home life of destitution and strict rules, and the gleeful if debauched carnival that he often explored, presented life in a disharmony of polarizing extremes. At the age of seven, his family emigrated to the United States and settled in New York City, but they returned to Austria just three years later. There, he grew up surrounded by the art nouveau scene, where Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele painted grotesque figures, Arthur Schnitzler wrote of the sordid interactions between men and women, and the music of Gustav Mahler and Arnold Schoenberg helped facilitate an atmosphere of relaxed amorality. Pleasure became the driving force of Austrian life, lending a carnivalesque air to the everyday. At fourteen, Sternberg left Austria for the New World to live with relatives and, eventually, acquired his first job in the movie business repairing film prints. He worked for World Film Company to edit and create intertitles on silent features, as many as fifty prints a year. During his below-the-line work, he absorbed a wealth of knowledge about directing, lighting, cinematography, and the visualization of motion pictures. He traveled back to Vienna, then England, taking a series of jobs as director’s assistant and working under the regal-sounding name Josef von Sternberg, modeled after his idol, director Erich von Stroheim. Not until 1925 did he make his independently financed feature debut, The Salvation Hunters, drawing the attention of the United Artists: Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., and Mary Pickford. He came to direct several films for Hollywood, chiefly Paramount, including an early gangster picture, Underworld (1929), and his first sound film, Thunderbolt (1929), before being coaxed to Germany by Pommer.

Conflicting accounts of how Dietrich came to be cast in The Blue Angel have plagued film legend, often by Dietrich herself. But what remains true is that, when no one else thought Marlene Dietrich was right for Lola Lola, Sternberg fought for her. In fact, Lola Lola was not the character’s name from Mann’s novel; she was originally named Rosa Fröhlich. Sternberg insisted on the change to echo the notorious character Lulu from Franz Wedekind’s plays Earth Spirit (1895) and Pandora’s Box (1904)—an iconic femme fatale of sexual liberation, murder, impassioned love, and tragic misfortune. UFA wanted to saturate the German, American, and British markets with the project by shooting two versions back-to-back, meaning the performers had to speak both German and English. Jannings spoke both well enough and had demonstrated as much on The Last Command. And while much of the production had been built around Jannings and his established celebrity, the problem of Lola remained. The production held an enormous casting call for the role, and virtually every performer in Germany responded, including Leni Riefenstahl. UFA wanted Louise Brooks or Greta Garbo, but they were unavailable or uninterested. Then, Pommer’s wife and actress Ruth Landshoff convinced Sternberg to attend a musical performance of a well-reviewed, jazzy, Chicago-set show that starred a woman with heavy-lidded eyes, a throaty voice, and an uncanny worldliness—and she spoke lines in English to boot. Although he wasn’t impressed by the show, Sternberg had made his choice for Lola that evening. UFA needed convincing that their most expensive production to date should feature a relative unknown.

Born in 1901 near Berlin, Maria Magdalene Dietrich changed her name as a child into the then-unheard-of “Marlene,” and with that, at an early age, demonstrated her desire to fashion herself into something else. She learned English from a nanny and governess, and at a young age, she aspired to become a violinist and entertainer. Within the first few years of her career as a stage artist in the early 1920s, she worked in cabaret, theater, vaudeville, musical revues, and both silent and sound film. By the end of her career, Dietrich’s experience would extend to radio, USO tours, television, concert halls, and Broadway. But Dietrich, ever the author of her life who derided biographers and journalists insistent on recorded fact, would continuously attempt to retell her life story as an entertainer and icon. She claimed that The Blue Angel was her first onscreen appearance and first major role. At the same time, film historians have counted some fourteen screen appearances by Dietrich before her first collaboration with Sternberg. Additionally, she performed on-stage in both classical and modern theatrical pieces, was well known in the Berlin cabaret scene, and had already begun to develop her persona as a singer whose costumes and behavior broke gender boundaries (she had been frequently seen in Berlin wearing men’s clothing, an underground fashion trend at the time). Dietrich’s already established glamour, cosmopolitanism, and outward indifference, thus allure, would be taken to new levels by Sternberg, who enhanced her existing traits through illumination—defining the contours of her face and airiness of her hair, while preserving the mystery behind her eyes through his use of light.

Born in 1901 near Berlin, Maria Magdalene Dietrich changed her name as a child into the then-unheard-of “Marlene,” and with that, at an early age, demonstrated her desire to fashion herself into something else. She learned English from a nanny and governess, and at a young age, she aspired to become a violinist and entertainer. Within the first few years of her career as a stage artist in the early 1920s, she worked in cabaret, theater, vaudeville, musical revues, and both silent and sound film. By the end of her career, Dietrich’s experience would extend to radio, USO tours, television, concert halls, and Broadway. But Dietrich, ever the author of her life who derided biographers and journalists insistent on recorded fact, would continuously attempt to retell her life story as an entertainer and icon. She claimed that The Blue Angel was her first onscreen appearance and first major role. At the same time, film historians have counted some fourteen screen appearances by Dietrich before her first collaboration with Sternberg. Additionally, she performed on-stage in both classical and modern theatrical pieces, was well known in the Berlin cabaret scene, and had already begun to develop her persona as a singer whose costumes and behavior broke gender boundaries (she had been frequently seen in Berlin wearing men’s clothing, an underground fashion trend at the time). Dietrich’s already established glamour, cosmopolitanism, and outward indifference, thus allure, would be taken to new levels by Sternberg, who enhanced her existing traits through illumination—defining the contours of her face and airiness of her hair, while preserving the mystery behind her eyes through his use of light.

Sternberg’s view of himself was an artist not unlike a painter or a poet who, rather than devote himself to portraying an accurate depiction of history or even reality, sought to explore psychological worlds with mood and atmosphere, lighting, and a meticulously chosen mise-en-scène from his artist’s toolkit. Shooting The Blue Angel at UFA studios in contemporary Berlin, Sternberg could not help but reflect the state of Germany at the time, which, after their defeat in 1918, sought to corrupt the country’s moral fiber as inflation and a lack of infrastructure led to destitution. While this atmosphere would eventually give the Nazi Party room to grow, Sternberg reflected its sad condition with the film’s narrative—as cruel schoolchildren mock Professor Rath and he succumbs to enraged, unintelligible madness in the final scenes. Elsewhere, UFA spared no expense to make The Blue Angel’s production among their most impressive to date. The newly implemented Klangfilm sound process allowed for audio and visuals, but the limited technology of the period meant the camera remained immobile in a soundproof booth with the director and cameraman. As Hollywood’s dubbing techniques and mobile microphones were not yet available in Germany, the camera in The Blue Angel barely moves, although each frame is a detailed composition. Sternberg was assisted by Günther Rittau, Fritz Lang’s cinematographer on Metropolis, and famed set designer Otto Hunte, another regular Lang collaborator. Hungarian costume designer Tihamer Várady designed Lola’s racy neckline and exposed, frilled undergarments, complete with visible stockings. Sternberg and company filled every shot with countless details to create the impression of a carnivalesque world into which Professor Rath loses himself over Lola Lola.

The Blue Angel is a familiar story from this period about the danger of the underworld, the nightlife—that desirous expanse outside of the safe, right and proper, but turgid bourgeois existence. It’s a place where flesh was for sale and adventure aligned with the limits and depths of human imagination. The film’s setting is far more sordid than those in later films starring Dietrich and directed by Sternberg. The Blue Angel nightspot could hardly be described as a cabaret; it is a rough place with a wild, beer-guzzling audience that watches a show in which the rotund, dispirited ladies on the ramshackle stage look frumpy and dejected—it’s a world in which, as Sternberg observed, “Toulouse-Lautrec would have turned a couple of handsprings.” The stage shows include a conjurer, a dancing bear, an unimpressed chorus line, and the seductress singer, Lola Lola. Backstage, a miserable clown named Auguste—wearing the same red nose, makeup, skull cap and wig, and oversized white collar that Rath will don later in the film—wanders about, inconsolably sad, though we know not why. Perhaps Auguste, too, has fallen in love with Lola and lost himself in the process, foreshadowing Rath’s eventual descent. Only later, when Rath joins the ranks of this motley crew, his face twisted and broken by the torment of his fanatical love, does it become apparent that he belongs with them. The beer hall is a twisted setting filled with outrageous figures, against which Lola stands out as a bastion of light and sexuality. How could Rath not be drawn to her?

Mann’s novel unabashedly attacked Rath, portraying him as a reflection of the current militarism and self-important arrogance of German society entrenched by the author’s contemporary Wilhelmine Empire. However strict Rath behaves early on in his role as a professor, he’s ultimately a weak man and the object of his students’ ridicule. And finally, his insecurities leave him vulnerable to a loss of Self. Rath’s students draw crude caricatures of him on his portfolio and the chalkboard, and when he learns of their activities at The Blue Angel and follows them there, they mock him, despite his later classroom punishments. With his students, Rath remains susceptible, which is perhaps why Lola can so easily seduce him. After his first encounter with Lola at the beer hall, he returns the next night and defends her from a sailor to whom the club owner planned to pimp Lola. This endears Rath to her, and he quickly becomes her protector and puppet. They sleep together and, after abandoning his station at the local college, he marries her and joins the traveling troupe of entertainers. Five years pass, with Rath performing as a clown in their show, but in that time, he has become possessive, impoverished, and ultimately the warped reflection of Auguste. When she finally betrays her husband by supplementing her income with the occasional paying lover, and with Mazeppa the strongman (Hans Albers), Rath becomes a loon—cuckooing like a madman as an extension of his stage act, he attacks Lola, until Mazeppa and others secure him in a straightjacket. With nothing and no one left, Rath breaks into his former classroom at the college, clings to his desk out of desperation and regret, and dies.

Mann’s novel unabashedly attacked Rath, portraying him as a reflection of the current militarism and self-important arrogance of German society entrenched by the author’s contemporary Wilhelmine Empire. However strict Rath behaves early on in his role as a professor, he’s ultimately a weak man and the object of his students’ ridicule. And finally, his insecurities leave him vulnerable to a loss of Self. Rath’s students draw crude caricatures of him on his portfolio and the chalkboard, and when he learns of their activities at The Blue Angel and follows them there, they mock him, despite his later classroom punishments. With his students, Rath remains susceptible, which is perhaps why Lola can so easily seduce him. After his first encounter with Lola at the beer hall, he returns the next night and defends her from a sailor to whom the club owner planned to pimp Lola. This endears Rath to her, and he quickly becomes her protector and puppet. They sleep together and, after abandoning his station at the local college, he marries her and joins the traveling troupe of entertainers. Five years pass, with Rath performing as a clown in their show, but in that time, he has become possessive, impoverished, and ultimately the warped reflection of Auguste. When she finally betrays her husband by supplementing her income with the occasional paying lover, and with Mazeppa the strongman (Hans Albers), Rath becomes a loon—cuckooing like a madman as an extension of his stage act, he attacks Lola, until Mazeppa and others secure him in a straightjacket. With nothing and no one left, Rath breaks into his former classroom at the college, clings to his desk out of desperation and regret, and dies.

Throughout the picture, Sternberg amasses visual layers for a world that did not resemble modern Berlin; rather, he creates a theatrical view of life in a carnivalesque combination of debauched decadence and enticing elegance. He admonished the notion of “dead space” between the camera and actors, and so he layered the space in-between with props, decoration, and intentional details—a treatment that’s heightened given the production’s inability to move the camera due to the requirements of early sound devices. Sternberg’s mood is established through countless obstructions. Lights, cords, hanging drapes, set decorations, and stuffed birds hang from the ceiling of The Blue Angel, while Lola’s dressing room is littered with costumes, picture frames, makeup cases, and garments draped over furniture, lending a sense of emotional confusion through visual stimuli. Sternberg also uses writing, drawings on the classroom chalkboard, racy postcards, and Lola’s posters to occupy our eyes. Black silhouettes and shapes often inhabit the foreground and obstruct the illuminated middle and backgrounds, marking a commonly used framing device. He also shoots through mirrors, showing Lola or Rath preparing for their shows by pointing the camera at the reflection. Compared to the emptiness and order of Rath’s classroom, or even his fussily organized bedroom, the beer hall is a disorienting alternative. Given such overstimulation, no wonder Rath falls for Lola—her world is alive. Her song “Naughty Lola” details the promises of that world in all its tawdry implications: “They call me naughty Lola/The wisest girl on earth/At home my pianola/It works for all it’s worth/Now I tell you a secret/Don’t hammer on the keys/For a little pianissimo/Is always bound to please.”

Sound and silence have a curious interplay throughout The Blue Angel. Although Sternberg incorporated the new sound technology, allowing Dietrich’s singing to become the film’s showcase, he also carefully orchestrated moments of silence to engage the viewer with the absence of sound. Dietrich’s songs and the cabaret settings, all of them shot live, were essential to Lola, as well as their establishing of Dietrich’s lasting persona. Sternberg defines Lola almost exclusively through her performances. When she sings “Falling in Love Again (Can’t Help It),” the tune tells us everything about the seductive character—establishing that Rath is to blame, not Lola, when he falls for someone whose métier requires her to entice and spellbind her public. Her sexy, engrossing stage numbers meant that Dietrich’s supporting performance walked away with the film, whereas Jannings seemed almost peripheral given the sensation that followed the performance. But as much as the film relied on songs, it relied on silence: the death of Rath’s bird, and the absence of its chirping, in the opening of the film; the contrast of his restless classroom and its absolute quiet; and the moments where, backstage, the sound of the performances ring with the opening and closing of stage doors. Most poignantly, Sternberg moved the camera in The Blue Angel only twice in noiseless, identical scenes of Rath at his desk, alone, first in the middle of the film, and then again at the tragic end.

Sternberg’s style bore an aestheticism that reflected his youthful days in carnivalesque Austria, which many in Hollywood translated not as a heightened or expressionistic take on reality but rather a pejorative melodrama or camp aesthetic. But Sternberg saw filmmaking as a form of personal expression, a typically European view not shared by many Hollywood craftsmen and journeyman directors. He embraced the synthetic quality of cinema, its ability to create emotion and atmosphere using light and shadow—these were the tools of motion picture filmmaking, not actors, not performances, and not even scripts. He often concentrated less on faces and more on inanimate objects, such as the above-described obstructions. Every detail in a Sternberg film, particularly The Blue Angel, on which he had untold artistic freedoms from UFA, was intentional. His use of transitions, fades, and overlapping footage that takes the viewer from one scene to the next, or sound from the oncoming scene that begins in the previous one, suggests he planned the structure of the film in detail beforehand, or at least insisted upon connectivity from moment to moment. His aestheticism is also evidenced in how he shoots his performers. He often lit Dietrich, as David Thompson observed, “like a spiritual presence in a tawdry world,” and he later shot Marian Marsh and Gene Tierney in similarly alluring light.

Sternberg’s style bore an aestheticism that reflected his youthful days in carnivalesque Austria, which many in Hollywood translated not as a heightened or expressionistic take on reality but rather a pejorative melodrama or camp aesthetic. But Sternberg saw filmmaking as a form of personal expression, a typically European view not shared by many Hollywood craftsmen and journeyman directors. He embraced the synthetic quality of cinema, its ability to create emotion and atmosphere using light and shadow—these were the tools of motion picture filmmaking, not actors, not performances, and not even scripts. He often concentrated less on faces and more on inanimate objects, such as the above-described obstructions. Every detail in a Sternberg film, particularly The Blue Angel, on which he had untold artistic freedoms from UFA, was intentional. His use of transitions, fades, and overlapping footage that takes the viewer from one scene to the next, or sound from the oncoming scene that begins in the previous one, suggests he planned the structure of the film in detail beforehand, or at least insisted upon connectivity from moment to moment. His aestheticism is also evidenced in how he shoots his performers. He often lit Dietrich, as David Thompson observed, “like a spiritual presence in a tawdry world,” and he later shot Marian Marsh and Gene Tierney in similarly alluring light.

For Sternberg, actors were icons on which he could create an exterior image from light or the absence thereof, transforming them into a beacon of some internal or thematic idea. They were, however, more like props than centers for emotion and introspectiveness. “An actor is chosen for his fitness to externalize an idea of mine, not an idea of his,” Sternberg once wrote, lending some insight into why his films offer few great performances. In his autobiography published in 1966, titled Fun in a Chinese Laundry after the 1901 short film, he claimed that no screenplay existed for The Blue Angel beyond his own detailed notes, an assertion that reveals his ego, while denying the work of screenwriters Carl Zuckmayer, Karl Vollmöller, and Robert Liebmann. Sternberg believed that his direction was central to any picture bearing his name. His view propelled the Svengali myth that early film historians used to define the relationship between Sternberg and Marlene Dietrich. Although Sternberg helped establish Dietrich as an icon of the silver screen, she defied his surface-level assignments for his performers with her indefinable mystique, her surprising dimensionality in their later collaborations, and her ability to maintain her status as a Hollywood legend long after their final films together.

When it debuted at the Gloria-Palast cinema in Berlin on April 1, 1930, The Blue Angel was celebrated throughout Germany. Sternberg’s direction was hailed, and Dietrich was called an overnight success, regardless of her decade in show business by that point. Dissent in Germany soon followed as critics panned the adaptation from Mann’s novel to the screen, from an intellectually and socially relevant work into an “unintelligent piece of philistinism,” according to the critic of Weltbühne, a magazine published by leftist intellectuals. In the coming years as the Nazis gained more power, Joseph Goebbels’ propaganda newspaper Völkischer Beobachter accused the film of perpetuating “a Jewish attempt to subvert and besmirch the German character and German educational values; here Jewish cynicism shows itself with a baseness that is seldom seen so openly.” The Blue Angel would not appear in Germany again until after World War II. For Dietrich, it would be her only role in a major German film in her native language. After she emigrated to America for Hollywood, many in Germany could not overlook that she refused Goebbels’ offers to make her the new face of German cinema and, instead, actively supported the United States war effort through USO performances, including several impassioned public comments against Hitlerism. In the U.S., The Blue Angel was released after her first Hollywood picture with Sternberg, Morocco (1930), which established her onscreen presence among American audiences before they endured the less cohesive English-language version of the UFA production.

Sternberg had developed an infatuation with Dietrich on the set of The Blue Angel, and over the next five years, he would fall in the same manner as many of her admirers in their collaborations. And why not? He had, after all, instructed her a great deal on how to control her behavior and appearance, and she mastered his education, even transcended it. For instance, he taught her to disguise the Germanness of her speaking voice by lessening her accent. If her pronunciation was not strictly American, it was not distinctly German either, but it allowed her to maintain a vampish otherness associated with femme fatale characters since Theda Bara and Garbo first seduced Western viewers with their accents. In her Hollywood career, she became an image of foreign sexuality, joining the ranks of Garbo, Maurice Chevalier, and later Ingrid Bergman as a non-native English-speaking performer on English-speaking screens. She also carried a sophistication that Americans associate with Europeans, and, like Sternberg, she veered away from the Hollywood norm of moral assurance—a quality associated with European talent. And she maintained this persona on and off-screen, and therefore, by simply being Marlene Dietrich, she could entice viewers. It seemed, as actress Lili Darvas remarked, that Dietrich was “great without doing anything at all.” This was the true quality of a star. But the notion that she did nothing mischaracterizes Dietrich and buys into the illusion.

Sternberg had developed an infatuation with Dietrich on the set of The Blue Angel, and over the next five years, he would fall in the same manner as many of her admirers in their collaborations. And why not? He had, after all, instructed her a great deal on how to control her behavior and appearance, and she mastered his education, even transcended it. For instance, he taught her to disguise the Germanness of her speaking voice by lessening her accent. If her pronunciation was not strictly American, it was not distinctly German either, but it allowed her to maintain a vampish otherness associated with femme fatale characters since Theda Bara and Garbo first seduced Western viewers with their accents. In her Hollywood career, she became an image of foreign sexuality, joining the ranks of Garbo, Maurice Chevalier, and later Ingrid Bergman as a non-native English-speaking performer on English-speaking screens. She also carried a sophistication that Americans associate with Europeans, and, like Sternberg, she veered away from the Hollywood norm of moral assurance—a quality associated with European talent. And she maintained this persona on and off-screen, and therefore, by simply being Marlene Dietrich, she could entice viewers. It seemed, as actress Lili Darvas remarked, that Dietrich was “great without doing anything at all.” This was the true quality of a star. But the notion that she did nothing mischaracterizes Dietrich and buys into the illusion.

Dietrich’s image was practiced and labored over, her persona both self-made and shaped early on by her impresario director. Later in life, Dietrich credited Sternberg with bringing out and developing a quality already within her, and then setting that quality within a light and shadow to cement its place in the cultural consciousness. However, many of her chosen styles were established on the stage before her appearance in The Blue Angel. She was well known to wear slacks or appear in a man’s tuxedo in her stage performances, a fashionable trend that she revisited in Sternberg collaborations like Morocco, Dishonored (1931), and Blonde Venus (1932). She continued to transgress gender boundaries while embracing androgyny and bisexuality in both life and her films with Sternberg and beyond. Those qualities were pure Dietrich. While the director gave Dietrich the tools and knowledge to control her onscreen persona in future films with some of Hollywood’s most celebrated directors, including Lubitsch, Alfred Hitchcock, Billy Wilder, and Orson Welles, she maintained her aura by upholding the exterior image at all times.

Her onscreen presence maintained a dark internal existence in many of her films, hinting at some quality that existed inside but would remain enigmatic. Dietrich’s ability to control her persona was so practiced and exacting that, by 1950, Hitchcock, who normally painstakingly storyboarded the lighting and camera movements before shooting began, allowed Dietrich to control the lighting of her scenes in Stage Fright. In a career that spanned more than 50 years through the twentieth century, she solidified her status as an icon. Dietrich’s image as Lola Lola was so well-established and innovated upon throughout her career that it became her calling card, informing not only her later Broadway appearances but also how other filmmakers referenced imagery associated with Lola. Bob Fosse adopted Lola’s stage presence for Cabaret (1972), a film set during the Weimar Republic entertainment scene; Liliana Cavani’s tale of Nazi sadomasochism, The Night Porter (1974), borrows Lola’s look, as does Luchino Visconti’s The Damned (1969); while Paul Verhoeven used “Naughty Lola” in his World War II actioner Black Book (2007)—all films that make connections between the cabaret scene of Germany and the Nazi Party. Such films redefine Dietrich’s image to create associations with Nazism and sadomasochism, but they also rethink notions of gender binarism—bringing out what Dietrich’s original screen presence so casually implied.

Together, Sternberg and Dietrich made films about the erotic powers of women over men. In doing so, they elevated her screen presence from that of a tawdry singer in The Blue Angel beer hall to a bastion of furtive sexual cues, tragic romance, and mythic reputation. Films like Morocco and Shanghai Express (1932) portray Dietrich as a legend, not in the making, but already made, as each film serves as another episode in the lost and storied lives of nightclub singer Amy Jolly or her woman about China, Shanghai Lily. Later, the secretive interior world of Dietrich’s onscreen presence is beautifully obstructed in The Scarlet Empress (1934) by furs, veils, lace, and other accouterments that shroud Dietrich in secretiveness, lending to her idealization through grand melodramatic fantasy. Among all of Sternberg’s films with Dietrich, she is most exposed in The Blue Angel, as her inscrutability would gradually become her main attribute as their collaboration continued. And ironically, as Sternberg frequently made films about men brought down by their weakness and susceptibility to women of desire, the director himself gave in to Dietrich. After their final collaboration on The Devil is a Woman in 1935, the two never worked together again, and Sternberg’s films were never the same. A secret affair between the two, with the director in the role of a lovesick man fatefully succumbing to a woman, is often attributed as the cause of Sternberg’s decline as a filmmaker.

Together, Sternberg and Dietrich made films about the erotic powers of women over men. In doing so, they elevated her screen presence from that of a tawdry singer in The Blue Angel beer hall to a bastion of furtive sexual cues, tragic romance, and mythic reputation. Films like Morocco and Shanghai Express (1932) portray Dietrich as a legend, not in the making, but already made, as each film serves as another episode in the lost and storied lives of nightclub singer Amy Jolly or her woman about China, Shanghai Lily. Later, the secretive interior world of Dietrich’s onscreen presence is beautifully obstructed in The Scarlet Empress (1934) by furs, veils, lace, and other accouterments that shroud Dietrich in secretiveness, lending to her idealization through grand melodramatic fantasy. Among all of Sternberg’s films with Dietrich, she is most exposed in The Blue Angel, as her inscrutability would gradually become her main attribute as their collaboration continued. And ironically, as Sternberg frequently made films about men brought down by their weakness and susceptibility to women of desire, the director himself gave in to Dietrich. After their final collaboration on The Devil is a Woman in 1935, the two never worked together again, and Sternberg’s films were never the same. A secret affair between the two, with the director in the role of a lovesick man fatefully succumbing to a woman, is often attributed as the cause of Sternberg’s decline as a filmmaker.

An oddity created by an Austrian-American director working with UFA during the Weimar Republic, The Blue Angel launched a legendary collaboration between Josef von Sternberg and Marlene Dietrich in Hollywood. Strangely, the film seems to anticipate their relationship as well. The partnership between the two talents, their ascension, and ultimate decline as an actor-director alliance suggests that not one individual was responsible for Dietrich’s lasting screen presence. Many believe that Dietrich was an entirely self-made, even feminist presence given her indefinable sexuality and independence, while others argue that Sternberg was the manipulative filmmaker who shaped her from clay. The truth, as usual, lies somewhere in-between. Would Dietrich have been able to create her image so dreamily, yet with a rustic earthiness and pansexuality that defines her screen presence, with a Hollywood journeyman filmmaker? Doubtful. And would von Sternberg have been able to render such a supreme example of femininity and sexuality without someone bearing the confidence, daring, and willingness to collaborate as Dietrich had? Certainly not. They worked together to explore Dietrich’s elusive attributes and solidify their many implications in physical form, from her pencil-thin eyebrows to the dramatic turns of her head to address a lover. The result of their collaboration, beginning on The Blue Angel, made both film history and an incomparable Hollywood legend.

Bibliography:

Bach, Steven. Marlene Dietrich: Life and Legend. University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

Baxter, John: Von Sternberg. University Press of Kentucky, 2010.

Mainon, Dominique and J. Ursini. Femme Fatale: Cinema’s Most Unforgettable Lethal Ladies. Limelight Editions, 2009.

Prawer, Siegbert S. The Blue Angel (Der Blaue Engel). London: British Film Institute, 2002.

Riva, Maria. Marlene Dietrich. Alfred A. Knopf, 1993.

Sarris, Andrew. The Films of Josef von Sternberg. Doubleday, 1966.

Studlar, Gaylyn. In the Realm of Pleasure: Von Sternberg, Dietrich, and the Masochistic Aesthetic. University of Illinois Press, 1988.

Spoto, Donald. Blue Angel: The Life of Marlene Dietrich. Doubleday, 1992.

Thompson, David. “Von Sternberg – Six Chapters in Search of an Auteur.” Sight & Sound, Vol. 20, no. 1, 2010 January, pp. 38-41.

von Sternberg, Josef. Fun in a Chinese Laundry. Secker and Warburg, 1966.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review