The Definitives

The Big Heat (1953)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

The Big Heat is a juicy and unflinching film noir whose brutal violence is matched by its sharp cynicism. In the film, a husband pulls his wife’s corpse from their blazing, bombed car. A twisted gangster rapes and burns women with cigarettes; later, the same psychopath throws a pot of scalding coffee into a woman’s face. But, in due course, the scalded woman returns the favor. Such sadistic violence sears a place in the viewer’s memory, revealing universal truths about the corruption of American power systems that support them, and how they diverge from the American Dream. And yet, on the surface, the film may seem like a standard B-grade noir of the classic Hollywood postwar era. The 1953 release was developed and produced under the enforced budgetary limitations of Columbia Pictures, a frugal studio that considered the film an average programmer. Director Fritz Lang tells the story in an efficient, economic, and highly structured manner, adopting a filmmaking style less expressive than his earlier work. Lang does not waste a single shot or formally indulge himself. Scene after scene, he compels a vicious pace, rich in both structure and symbolism, aligning with the film’s acrid worldview that saturates its director’s body of work—themes of oppressive paranoia, psychological torment, and rampant moral corruption.

Despite its standard Hollywood construction, The Big Heat remains uncharacteristic for how it inverts the usual film noir tropes. Its most virulent crimes happen not obscured by shadow or in dark alleyways, but in well-lit apartments, surrounded by bought-and-paid-for officials. The hero, Dave Bannion (Glenn Ford), is an idealist detective and virtuous family man. He has no sordid past, nothing to apologize for, and everything a postwar man should have: a quiet home; a loving, tender marriage to a supportive wife, Katie (Jocelyn Brando, sister of Marlon); a young rugrat to raise; and moral certainty. But Bannion falls into “hate binge” when confronted by the cruel violence and widespread corruption in his average American city, called Kenport. And while he cannot bring himself to break his own moral code, the women around him, by mere association, suffer for his internal conflict. Bannion presents a rare homme fatale who, however inadvertently, spells doom for every woman with whom he comes in contact. And while women have the most interesting roles in this exquisitely acted film, most have been fated by their contact with the tragic hero, a living symbol of the need to persist in the face of America’s systemic corruption, crime, and injustice.

The Big Heat debuted in the midst of a moviegoing decline after World War II. Audiences had plenty to occupy themselves, from creating the baby-boom generation to listening to the radio, watching the newfangled invention of television, and spending their money on automobiles and other suburban conveniences. Regardless of the declining box-office, Columbia Pictures continuously made money; they always had. Jack Cohn and his brother Harry, along with close friend Joe Brandt, started their motion picture company in 1918 as Cohn-Brandt-Cohn Film Sales, eventually changing the name to the regal sounding Columbia Pictures in 1924. When other studios struggled, their money-mindful company turned profits, even throughout the Great Depression. Much later, they were among the first studios to sell their backlog to television, as well as produce TV dramas in their newly formed offshoot, Screen Gems. To compete with television theatrically, Columbia embraced new technical formats such as widescreen, CinemaScope, color, and early forms of 3-D. Film scholar Colin McArthur notes that, in 1953, most of Columbia’s attention was on their production of From Here to Eternity, a sweeping wartime drama based on James Jones’ best-selling novel. Few of the Hollywood trades noticed a B-picture like The Big Heat quietly developing in the shadows.

The Big Heat debuted in the midst of a moviegoing decline after World War II. Audiences had plenty to occupy themselves, from creating the baby-boom generation to listening to the radio, watching the newfangled invention of television, and spending their money on automobiles and other suburban conveniences. Regardless of the declining box-office, Columbia Pictures continuously made money; they always had. Jack Cohn and his brother Harry, along with close friend Joe Brandt, started their motion picture company in 1918 as Cohn-Brandt-Cohn Film Sales, eventually changing the name to the regal sounding Columbia Pictures in 1924. When other studios struggled, their money-mindful company turned profits, even throughout the Great Depression. Much later, they were among the first studios to sell their backlog to television, as well as produce TV dramas in their newly formed offshoot, Screen Gems. To compete with television theatrically, Columbia embraced new technical formats such as widescreen, CinemaScope, color, and early forms of 3-D. Film scholar Colin McArthur notes that, in 1953, most of Columbia’s attention was on their production of From Here to Eternity, a sweeping wartime drama based on James Jones’ best-selling novel. Few of the Hollywood trades noticed a B-picture like The Big Heat quietly developing in the shadows.

The film opens with a suicide. When corrupt officer Tom Duncan blows his brains out, his widow Bertha (Jeanette Nolan) uses the suicide note’s contents to blackmail local crime boss Mike Lagana (Alexander Scourby). She demands regular payoffs from Lagana, warning that the note will be released if she suddenly dies. During the investigation, she tells Bannion her husband killed himself due to ill health, and that “Everything Tom ever did was clean and wholesome.” As Bannion checks Bertha’s story, he meets Duncan’s mistress Lucy Chapman (Dorothy Green) at one of Lagana’s restaurants called The Retreat. Lucy tells Bannion that Duncan was not ill—that he had planned to divorce Bertha. The next day, Bannion learns Lucy has been killed by Lagana’s goons. It’s an “old-fashioned sort of killing, Prohibition-kind” says the coroner, who reports that Lucy was also molested and covered in cigarette burns. After Bannion asks Bertha about Lucy’s claims, the widow files a complaint with his superiors. Lt. Ted Wilks (Willis Bouchey) tells Bannion to back down, which he might have done if not for Lagana’s men making a threatening phone call to his home. Despite the danger, Katie tells him, “Don’t you compromise,” and he proceeds to confront Lagana with a promise to take him down.

Insulted by how he was disrespected, Lagana responds by ordering a hit on Bannion. But the resulting car bomb accidentally blows up Katie in one of cinema’s most shocking deaths. In the aftermath, Bannion’s superiors show their spinelessness and corruption when they decline to go after Lagana. Bannion is enraged and refuses to be consoled by the police chaplain, rejecting his religious morality and the law by resigning from the force and vowing to investigate Lagana on his own. He begins by scouting underworld scrapheaps and mechanic shops for anyone who might know a car bomb maker, and after getting rebuffed by a slimeball owner (Dan Seymour), the crippled junkyard secretary Selma (Edith Evanson) feeds him information about Larry Gordon (Adam Williams). Bannion confronts Gordon and nearly strangles him out of rage before stopping himself. He cannot bring himself to kill, so he spreads the word that Gordon is a rat. Not long after, Gordon is found dead. Meanwhile, at The Retreat, Bannion sees Vince Stone (Lee Marvin), Lagana’s second-in-command, punish a woman by burning her with a cigarette butt. Bannion interjects, intimidating Stone out of the club. Seeing Bannion’s heroics in defense of a woman, Stone’s lady friend Debby (Gloria Grahame) offers to buy him a drink, and when he turns her down, she decides to invite herself to Bannion’s hotel room. She looks around and sizes up the place, “Say, I like this: Early Nothing.” Bannion asks, “Why did you come up?” She replies, “Let’s call it research or something.” But Bannion rebuffs her advance.

Insulted by how he was disrespected, Lagana responds by ordering a hit on Bannion. But the resulting car bomb accidentally blows up Katie in one of cinema’s most shocking deaths. In the aftermath, Bannion’s superiors show their spinelessness and corruption when they decline to go after Lagana. Bannion is enraged and refuses to be consoled by the police chaplain, rejecting his religious morality and the law by resigning from the force and vowing to investigate Lagana on his own. He begins by scouting underworld scrapheaps and mechanic shops for anyone who might know a car bomb maker, and after getting rebuffed by a slimeball owner (Dan Seymour), the crippled junkyard secretary Selma (Edith Evanson) feeds him information about Larry Gordon (Adam Williams). Bannion confronts Gordon and nearly strangles him out of rage before stopping himself. He cannot bring himself to kill, so he spreads the word that Gordon is a rat. Not long after, Gordon is found dead. Meanwhile, at The Retreat, Bannion sees Vince Stone (Lee Marvin), Lagana’s second-in-command, punish a woman by burning her with a cigarette butt. Bannion interjects, intimidating Stone out of the club. Seeing Bannion’s heroics in defense of a woman, Stone’s lady friend Debby (Gloria Grahame) offers to buy him a drink, and when he turns her down, she decides to invite herself to Bannion’s hotel room. She looks around and sizes up the place, “Say, I like this: Early Nothing.” Bannion asks, “Why did you come up?” She replies, “Let’s call it research or something.” But Bannion rebuffs her advance.

Debby returns to Stone’s apartment where she’s confronted about her encounter with Bannion. Stone knows what she’s been up to; her calls her a liar and then throws scalding coffee in her face, leaving her permanently scarred, monstrous even. Given that Police Commissioner Higgins (Howard Wendell) was playing cards at Stone’s apartment at the time of the attack, Debby knows there’s no use reporting Stone. Instead, she tells Bannion all about Lagana’s operation, and how the widow Duncan has a note that can put Lagana away. Bannion confronts Bertha and, much as he did with Gordon, nearly strangles her trying to get the note, knowing it will expose Lagana if she dies. He cannot cross that line, however. Knowing Bannion is too moral to do what needs to be done, Debby visits Bertha. “We’re sisters under the mink,” Debby tells her in a famous line, and then kills her, ensuring that Duncan’s suicide note will expose Lagana. Next, Debby visits Stone’s apartment and surprises him by throwing a pot of hot coffee in his face. Scalded and screaming, Stone shoots her. Bannion arrives and, after a shootout, has Stone on his knees. Bannion could kill Stone and no one would know. But he stops himself. As other policemen arrive and take Stone away, Bannion comforts Debby in her last moments before death, and afterward, returns to the police force.

Such stories about good cops facing crime and corruption were popular in Hollywood in the 1950s, partly due to TV’s Dragnet (1951-1959). And so, Columbia saw an opportunity in William P. McGivern’s source novel. Written in the hard-boiled tradition of crime novelists such as James M. Cain, Raymond Chandler, and Dashiell Hammett from the previous decade, McGivern’s novel was published in seven parts in the Saturday Evening Post between December 1952 and February 1953. Columbia purchased the rights to McGivern’s story in January 1953, before the serial had completed, and put producer Robert Arthur in charge of its development. Sydney Boehm, a screenwriter with several crime pictures to his credit, was hired to adapt the material. Boehm had been a crime reporter for the New York Evening Journal before taking a screenwriting job in Hollywood following World War II, eventually writing more than fifty crime scenarios for the screen. Boehm also adapted McGivern’s Rogue Cop for MGM in 1954. In his adaptation of The Big Heat, Boehm kept close to the original story, mainly cutting extraneous characters and locations. McGivern’s basic plot remains intact, aside from the book’s procedural detail that occupies the first half. The resolution also differs: Rather than Stone shooting Debby after she scalds him, she commits suicide—a detail altered to conform to Bannion’s Christian sympathy. McGivern’s Bannion is also an optimistic philosopher and reader of humanists like Saint John of the Cross, Emmanuel Kant, Baruch Spinoza, and George Santayana, while specifically decrying less hopeful minds as Friedrich Nietzsche and Arthur Schopenhauer. In the film, Bannion does not discuss anything approaching a philosophy beyond his moral certitude.

Such stories about good cops facing crime and corruption were popular in Hollywood in the 1950s, partly due to TV’s Dragnet (1951-1959). And so, Columbia saw an opportunity in William P. McGivern’s source novel. Written in the hard-boiled tradition of crime novelists such as James M. Cain, Raymond Chandler, and Dashiell Hammett from the previous decade, McGivern’s novel was published in seven parts in the Saturday Evening Post between December 1952 and February 1953. Columbia purchased the rights to McGivern’s story in January 1953, before the serial had completed, and put producer Robert Arthur in charge of its development. Sydney Boehm, a screenwriter with several crime pictures to his credit, was hired to adapt the material. Boehm had been a crime reporter for the New York Evening Journal before taking a screenwriting job in Hollywood following World War II, eventually writing more than fifty crime scenarios for the screen. Boehm also adapted McGivern’s Rogue Cop for MGM in 1954. In his adaptation of The Big Heat, Boehm kept close to the original story, mainly cutting extraneous characters and locations. McGivern’s basic plot remains intact, aside from the book’s procedural detail that occupies the first half. The resolution also differs: Rather than Stone shooting Debby after she scalds him, she commits suicide—a detail altered to conform to Bannion’s Christian sympathy. McGivern’s Bannion is also an optimistic philosopher and reader of humanists like Saint John of the Cross, Emmanuel Kant, Baruch Spinoza, and George Santayana, while specifically decrying less hopeful minds as Friedrich Nietzsche and Arthur Schopenhauer. In the film, Bannion does not discuss anything approaching a philosophy beyond his moral certitude.

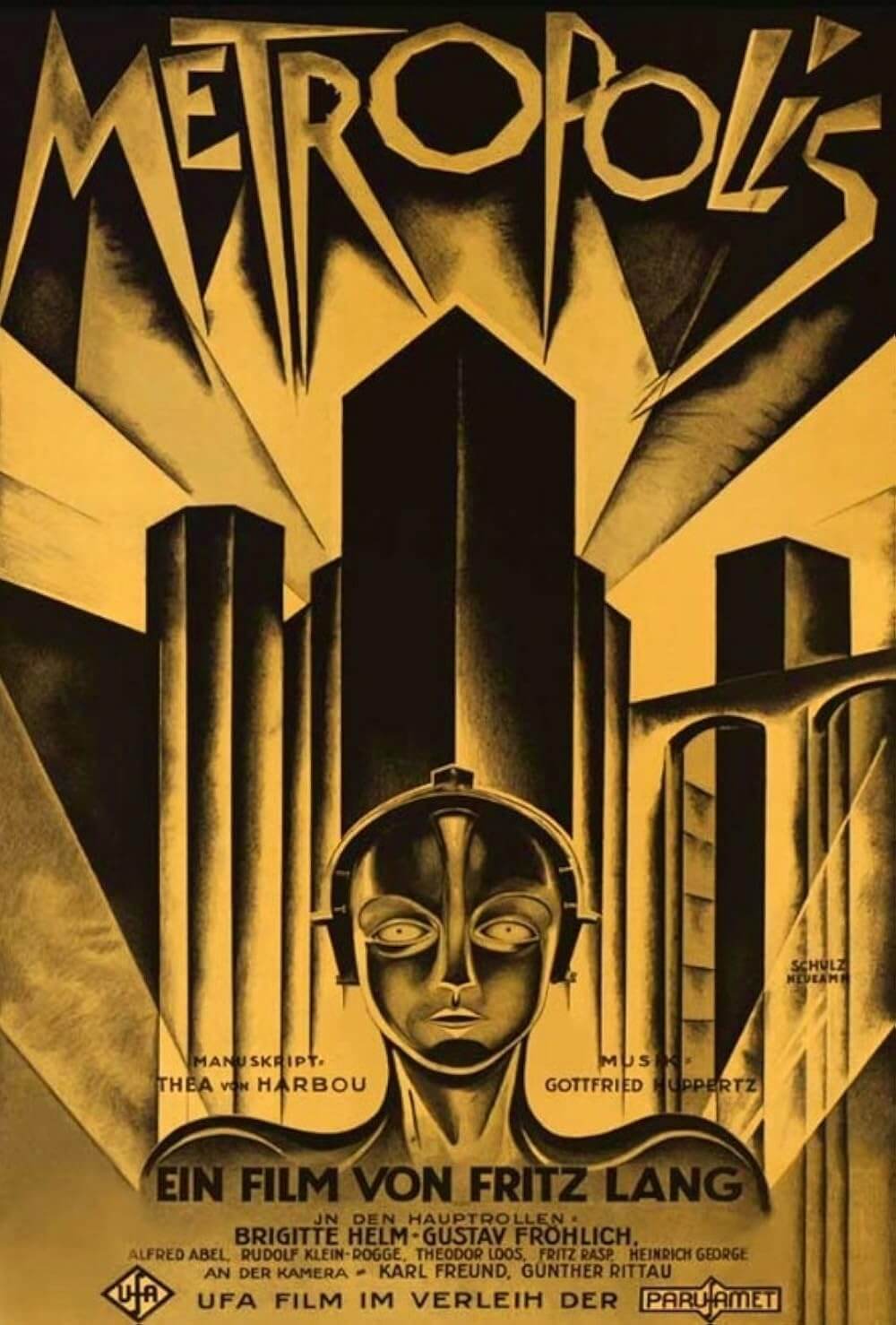

But The Big Heat takes place in a world where Nietzschean and Schopenhauerian views of nihilism and injustice seem to rule. It’s a world suited for its director. After thriving in the German film industry—making masterpieces like Dr. Mabuse: The Gambler (1922), Metropolis (1927), and M (1931)—Fritz Lang was courted by Joseph Goebbels to run UFA. But Lang’s Jewish-born Catholic mother gave him cause to escape Hitler’s Germany. It was independent Hollywood mogul David O. Selznick who finally convinced Lang to flee, selling the director on “himself, MGM, and America—in that order,” according to Patrick McGilligan’s biography of Lang. The transition made sense for all involved, as the director’s films were already shown in America by MGM. After arriving in Hollywood, Lang went on to work for nearly every major studio. And though he made dramas, adventures, fantasies, and science-fiction stories in Germany, he became known primarily for thrillers in the U.S., delivering titles like Fury (1936), Man Hunt (1941), Hangmen Also Die! (1943), and Scarlet Street (1945)—films that dealt with warped minds, obsessed men, prostitutes, and social torture. In early January of 1953, Lang had just started at Columbia when he was given a copy of Boehm’s screenplay.

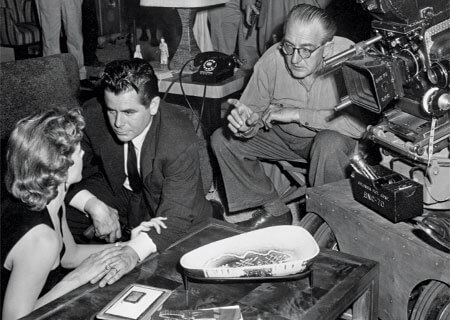

Lang joined the production of The Big Heat on February 20, 1953. As Gerard Leblanc and Brigitte Devismes’ book Le Double Scénario chez Fritz Lang notes, the director began his typical process of adding notes on aesthetics and formal choices into the script. Among his changes, he made Bannion a symbol of the American everyman whom Lang loved to torment in his films. In Lang’s hands, Bannion would become representative of an idealistic worldview that is repeatedly shattered in a corrupt world. Over the next two months, Glenn Ford and Gloria Grahame’s casting hit the trades, and the shoot was announced in The Hollywood Reporter in mid-March, reportedly lasting for twenty-eight days. Ford, an introspective Quebec-born actor, had a one-film-per-year contract with Columbia and was perceived as a reliable but unexceptional performer; still, he was capable of surprising, subtle emotional touches here, and in other work such as Jubal (1956) and 3:10 to Yuma (1957). Lang proudly maintained the reputation of a taskmaster over his performers. Though the most outlandish stories of his autocratic methods were behind him, he clashed with Grahame, whose ego on-set was emboldened by her recent Oscar victory for The Bad and the Beautiful just a few weeks before filming on The Big Heat began. The production followed a rushed filming and distribution schedule, shooting for cheap in black-and-white and the boxy, old-fashioned standard Academy aspect ratio—not the emergent prestige camera or formal types.

Lang joined the production of The Big Heat on February 20, 1953. As Gerard Leblanc and Brigitte Devismes’ book Le Double Scénario chez Fritz Lang notes, the director began his typical process of adding notes on aesthetics and formal choices into the script. Among his changes, he made Bannion a symbol of the American everyman whom Lang loved to torment in his films. In Lang’s hands, Bannion would become representative of an idealistic worldview that is repeatedly shattered in a corrupt world. Over the next two months, Glenn Ford and Gloria Grahame’s casting hit the trades, and the shoot was announced in The Hollywood Reporter in mid-March, reportedly lasting for twenty-eight days. Ford, an introspective Quebec-born actor, had a one-film-per-year contract with Columbia and was perceived as a reliable but unexceptional performer; still, he was capable of surprising, subtle emotional touches here, and in other work such as Jubal (1956) and 3:10 to Yuma (1957). Lang proudly maintained the reputation of a taskmaster over his performers. Though the most outlandish stories of his autocratic methods were behind him, he clashed with Grahame, whose ego on-set was emboldened by her recent Oscar victory for The Bad and the Beautiful just a few weeks before filming on The Big Heat began. The production followed a rushed filming and distribution schedule, shooting for cheap in black-and-white and the boxy, old-fashioned standard Academy aspect ratio—not the emergent prestige camera or formal types.

In 1953, there had been numerous complaints made to the Production Code Administration by the U.S. State Department, citing grumbles from several foreign governments about the high level of violence in Hollywood imports. Eyes turned to The Big Heat’s intended opening shot in which Duncan kills himself. The original script called for the shot to show the gun pressed against Duncan’s head. Arthur worked with Lang to appease censors, creating a shot where the camera captures only Duncan’s hand reaching for the gun; the audience then hears the shot and sees his body fall face-down on his desk. Aside from brief delays such as this, the production wrapped fast and on time. The short turnaround was not uncommon for a studio programmer, speaking further of Columbia’s unexceptional treatment of the film and their consideration of its B-picture status. Test screenings commenced in August, with review screenings in September, followed by an October release. But these month-long breaks suggested Columbia had more important things on their mind—namely, From Here to Eternity, which opened in August of 1953—and could not be bothered with a comparatively small release among their more than forty titles debuting that year. Accordingly, The Big Heat received an average box-office performance and, as a Columbia property, remained overshadowed by From Here to Eternity, which went on to win eight of its thirteen Academy Award nominations (including Best Picture and Best Director). The Big Heat’s largely dismissive reviews both in the U.S. and abroad called it “craftsmanlike” but otherwise undistinguished.

Among the few who acknowledged the film’s greatness early on were writer Manny Farber and critic-turned-director Lindsay Anderson. The latter wrote a review in Sight and Sound, calling The Big Heat “more satisfying than many more [of Lang’s] ambitious works.” Though Lang was a well-known visualist whose films often contained virtuoso camerawork, by the late 1940s, he no longer believed that elaborate visuals or special FX were necessary to filmmaking. “The more the audience is absorbed in the story and the more they forget the camera angles, the sly tricks of direction, and the director’s ‘touch,’ the better the picture is,” he told an interviewer. Lang had come to set aside his German expressionist sense to embrace classic Hollywood film grammar, a comparatively ordinary mode the audience was accustomed to seeing. Part of the reason was out of necessity. Lang had to work fast to suit the tighter budgets of the postwar Hollywood decline in box-office attendance. He shot entirely on soundstages on the Columbia lot, and the result looks plain, forcing the viewer to view it objectively, despite the expressiveness of the narrative material. There are no grand movements employed by cinematographer Charles Lang; no unnecessary flourishes that draw attention to themselves. It might seem workmanlike, except everything onscreen has been meticulously staged and arranged for a symbolic understanding.

Among the few who acknowledged the film’s greatness early on were writer Manny Farber and critic-turned-director Lindsay Anderson. The latter wrote a review in Sight and Sound, calling The Big Heat “more satisfying than many more [of Lang’s] ambitious works.” Though Lang was a well-known visualist whose films often contained virtuoso camerawork, by the late 1940s, he no longer believed that elaborate visuals or special FX were necessary to filmmaking. “The more the audience is absorbed in the story and the more they forget the camera angles, the sly tricks of direction, and the director’s ‘touch,’ the better the picture is,” he told an interviewer. Lang had come to set aside his German expressionist sense to embrace classic Hollywood film grammar, a comparatively ordinary mode the audience was accustomed to seeing. Part of the reason was out of necessity. Lang had to work fast to suit the tighter budgets of the postwar Hollywood decline in box-office attendance. He shot entirely on soundstages on the Columbia lot, and the result looks plain, forcing the viewer to view it objectively, despite the expressiveness of the narrative material. There are no grand movements employed by cinematographer Charles Lang; no unnecessary flourishes that draw attention to themselves. It might seem workmanlike, except everything onscreen has been meticulously staged and arranged for a symbolic understanding.

The film’s plot adheres to an ideal classic Hollywood structure described by David Bordwell that binds its characters to laws of narrative cause-and-effect, a structure that creates parallels throughout the story. For instance, if Debby getting scalded with coffee is a cause, then the effect is Debby scalding Stone in return. When Bannion tells Debby that he could not bring himself to kill the widow Duncan, the effect is Debby killing her for him. Along with the story following a traditional three-act structure of setup, confrontation, and resolution, such studio-enforced formulas and generalities have been subverted by Lang’s subtle coding of characters and scenes. Consider how, when Lt. Wilks tells Bannion to stop pestering Duncan, he does so from his office washroom, washing his hands and absolving himself of any responsibility. By contrast, Bannion meets Selma, a kindly junkyard informant who, in spite of being trapped in several prisons—behind wire fences, in a crippled body, forced to do bookkeeping for a crook—tries to do the right thing by helping Bannion locate Gordon. Or consider how, when Bannion searches for a bomb maker, the vehicle graveyard evokes Katie’s death in aching ways. Similarly, Bannion avoids visiting his daughter, as if his avoidance allows him to forget his fatherly duties and become a human beast. Perhaps his daughter is the sole reason Bannion does not kill Gordon, the widow Duncan, and Stone when he had the chance.

Lang delivers a film on the brink. Bannion walks on lines between good and evil, criminal action and law, morality and corruption. In order for Bannion to remain the noble hero, the narrative must bring him close to the edge but never allow him to go over. Lucy’s brutal torture and murder sets him on a willfully self-destructive confrontation with Lagana. But if Lucy’s death causes Bannion to act out, imagine how he feels when Katie dies. Bannion remains between darkness and light, always just about to kill someone and disrupt the moral code he values so much. Faced with his own potential for pure rage and base morals, the very things he’s trying to fight against, he never submits. As mentioned above, he nearly kills Gordon and the widow Duncan (in a scene that mirrors Stone’s attack on Debby) with his bare hands, and he could have killed Stone point-blank, but he stops himself. Instead, he comforts Debby in her final moments, eventually telling her about Katie, which he refused to do before. McArthur explains that, in her final moments, Debby provides Bannion with a “talking cure” by listening to him talk about his wife. In effect, Debby redeems Bannion by sacrificing her own morality and life to protect him, and thus Bannion never betrays his humanity or moral code.

Lang delivers a film on the brink. Bannion walks on lines between good and evil, criminal action and law, morality and corruption. In order for Bannion to remain the noble hero, the narrative must bring him close to the edge but never allow him to go over. Lucy’s brutal torture and murder sets him on a willfully self-destructive confrontation with Lagana. But if Lucy’s death causes Bannion to act out, imagine how he feels when Katie dies. Bannion remains between darkness and light, always just about to kill someone and disrupt the moral code he values so much. Faced with his own potential for pure rage and base morals, the very things he’s trying to fight against, he never submits. As mentioned above, he nearly kills Gordon and the widow Duncan (in a scene that mirrors Stone’s attack on Debby) with his bare hands, and he could have killed Stone point-blank, but he stops himself. Instead, he comforts Debby in her final moments, eventually telling her about Katie, which he refused to do before. McArthur explains that, in her final moments, Debby provides Bannion with a “talking cure” by listening to him talk about his wife. In effect, Debby redeems Bannion by sacrificing her own morality and life to protect him, and thus Bannion never betrays his humanity or moral code.

In his review of The Big Heat in the January 1954 issue of Cahiers du Cinéma, Francois Truffaut pointed out Lang’s theme in the film, and perhaps in all his films: “Man struggling along against a universe which is half-hostile, half-indifferent.” Lang’s personal, fatalistic worldview seemed to emerge in his American film noirs, presenting a fissure between his German and Hollywood work. His Hollywood films often revealed an institutional or social blight operating in the world. He had experienced it firsthand, not only in Hitler’s Germany but prior to making The Big Heat, when Lang had to defend himself from the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), which accused the director of being a communist. After he was cleared, The Big Heat was his first film. Lang liked the story because Bannion stands up for what he believes by taking action. The director felt ashamed about having to leave Germany by running away from Hitler—a hero like Bannion would have stood up to him. In the film, Lagana runs the city; he has rigged an upcoming election and has most of the police force on his payroll. “Everyone knows” who runs the town, but no one does anything about it. But even after Bannion takes down Lagana and defeats the film’s corrupt powers, Lang refuses an entirely Hollywood ending. He does not show Bannion reunited with his daughter. The final scene takes place in the police department. Bannion heads out to investigate a hit-and-run. On his way out the door, in the background, he walks by a poster that shows a man rolling up his sleeve. “Give blood now” reads the poster, suggesting Bannion must roll up his sleeve and continue to face the horrors of the world.

To establish the source of Bannion’s conflicted morality and the cruel universe he inhabits, Lang provides an ideal woman in Katie, a character who contrasts the film’s criminal underworld. She’s a rare kind of character, the sort every white American male in a 1950s audience could see themselves marrying, however unmodern her role may be to contemporary eyes. Their marriage is incredibly cute, and their charmed, rather frisky husband-wife dynamic proves rare for classic Hollywood cinema (outside of Nick and Nora Charles in The Thin Man series). Take Katie’s intimacy in what Bannion later describes as her “sampler” quality: “She’d take sips of my drink and puffs on my cigarette. Sometimes she used to taste the food off my plate. We got a big kick out of that.” And though she performs the typified duties of a 1950s homemaker—the steaks are in the oven, their daughter has been put to bed, she lights her husband’s cigarette, and always has a drink ready for him—she’s also a sexual presence: Katie calls their daughter “angelic all day, but at night she’s a holy terror.” Her husband replies, “That’s the way I usually describe you.” She’s not the cardboard housewife of a disinterested husband, as in most film noirs; her domesticity does not require that a femme fatale facilitate a sexualized alternative. Katie has it all, a family and sexual desire, and so when she dies, it is unexpected and horrifying. The viewer feels her loss through Bannion’s stony presence and lack of joy thereafter, and his unwillingness to feel a part of something—even as a parent. Her death elevates an already intense case to catch Lagana and Stone, Lucy’s killers, and the men who drove Duncan to suicide.

To establish the source of Bannion’s conflicted morality and the cruel universe he inhabits, Lang provides an ideal woman in Katie, a character who contrasts the film’s criminal underworld. She’s a rare kind of character, the sort every white American male in a 1950s audience could see themselves marrying, however unmodern her role may be to contemporary eyes. Their marriage is incredibly cute, and their charmed, rather frisky husband-wife dynamic proves rare for classic Hollywood cinema (outside of Nick and Nora Charles in The Thin Man series). Take Katie’s intimacy in what Bannion later describes as her “sampler” quality: “She’d take sips of my drink and puffs on my cigarette. Sometimes she used to taste the food off my plate. We got a big kick out of that.” And though she performs the typified duties of a 1950s homemaker—the steaks are in the oven, their daughter has been put to bed, she lights her husband’s cigarette, and always has a drink ready for him—she’s also a sexual presence: Katie calls their daughter “angelic all day, but at night she’s a holy terror.” Her husband replies, “That’s the way I usually describe you.” She’s not the cardboard housewife of a disinterested husband, as in most film noirs; her domesticity does not require that a femme fatale facilitate a sexualized alternative. Katie has it all, a family and sexual desire, and so when she dies, it is unexpected and horrifying. The viewer feels her loss through Bannion’s stony presence and lack of joy thereafter, and his unwillingness to feel a part of something—even as a parent. Her death elevates an already intense case to catch Lagana and Stone, Lucy’s killers, and the men who drove Duncan to suicide.

With Katie’s wholesome yet alluring domesticity fixed, every other woman in the film seems less pure, less sexy, and somehow broken, none more so than Debby—a bubbly yet dim beauty similar to Jean Peters in Pickup on South Street, also released in 1953. In Katie’s wake, Bannion claims he wouldn’t touch Debby “with a ten-foot pole,” but there’s something between the two more than just a detective pumping a witness for information on Katie’s killers. Regardless, Debby remains caught between good and evil, teetering to the opposite side of Bannion—attracted by the lifestyle crime affords her. She tells him, “I’ve been rich and I’ve been poor. Believe me, rich is better.” When we first meet her, she lives the high life with Stone in his ritzy apartment, ever lounging around and always with a drink in hand. Her looks define her at first. She frequently regards herself in the mirror, checking her hair and makeup, while people tell her, “That’s a real pretty kisser.” But Debby’s use of mirrors suggests her duality, her desire for luxury juxtaposed by an admiration of Bannion’s moral certainty. She later becomes two-faced, literally and figuratively, when Stone scalds her and makes her division a reality. To be sure, The Big Heat seems to establish Debby’s face as pretty if only to make Stone’s attack (he shouts, “I’ll fix you and your pretty face!”) and the resultant scarring all the more horrific and symbolic. Of course, the very notion that anyone would ever drink the bubbling, boiling-hot coffee limits the logic of the scene. Lang later told Peter Bogdanovich, “I wonder how many women who have thrown hot coffee in their husbands’ faces were very disappointed with the result and said, ‘Lang is a lousy director.’” With Debby’s face now half-burned, half normal, her appearance reflects her two-facedness and her broken existence. But her scarring serves a purpose within the narrative: it commits Bannion to his cause, perhaps reminding him of his burned wife, and also removes her as a potential cure for his grief and rage.

The Big Heat’s theme of violence against women reveals a morbid trend in Hollywood film noirs, both within the film itself and the hard-boiled crime genre as a whole. Stone is a character defined by his taste for hurting women, beyond coffee. Lucy Chapman’s body is found riddled with cigarette burns; she died “after beating and torture” in a “sex crime,” according to the coroner. Given how Stone burns a woman with a cigarette at The Retreat, impliedly Stone is Lucy’s killer, and a rapist. Before scalding Debby, he slaps her several times and twists her arm behind her back when he confronts her about Bannion. He shouts, “You pig! You lying pig!”—suggesting he sees women as animals ripe for slaughter. Finally, he shoots Debby after receiving his coffee comeuppance. Lang built Stone into a psychosexual villain after growing fascinated by Lee Marvin’s upper lip, how its curve suggested something sadistic and perverse. Accordingly, Marvin plays the role as if Stone enjoys hurting women. When the character tosses hot coffee in Debby’s face, the camera does not have sympathy for Debby; it turns to Stone, and the audience recoils in the vicious pleasure he takes from seeing Debby shriek in pain.

The Big Heat’s theme of violence against women reveals a morbid trend in Hollywood film noirs, both within the film itself and the hard-boiled crime genre as a whole. Stone is a character defined by his taste for hurting women, beyond coffee. Lucy Chapman’s body is found riddled with cigarette burns; she died “after beating and torture” in a “sex crime,” according to the coroner. Given how Stone burns a woman with a cigarette at The Retreat, impliedly Stone is Lucy’s killer, and a rapist. Before scalding Debby, he slaps her several times and twists her arm behind her back when he confronts her about Bannion. He shouts, “You pig! You lying pig!”—suggesting he sees women as animals ripe for slaughter. Finally, he shoots Debby after receiving his coffee comeuppance. Lang built Stone into a psychosexual villain after growing fascinated by Lee Marvin’s upper lip, how its curve suggested something sadistic and perverse. Accordingly, Marvin plays the role as if Stone enjoys hurting women. When the character tosses hot coffee in Debby’s face, the camera does not have sympathy for Debby; it turns to Stone, and the audience recoils in the vicious pleasure he takes from seeing Debby shriek in pain.

Misogynistic violence often diffuses or incites an unruly femme fatale in film noirs. The classic femme fatale resists domesticated roles and seeks independence, often through violence or the manipulation of men. Everyone around them seems to die, whether by direct or indirect action on her part. But the genre itself attempts to restore domestic order to the femme fatale by eliminating her. In Out of the Past (1947), Jane Greer’s femme fatale kills her way to freedom only to be gunned down by police; in both Double Indemnity (1944) and The Lady from Shanghai (1948), the respective femmes fatales scheme their way out of bad marriages and get shot for their deceptions. This thematic pattern suggests violence against women restores order to the world and presents a kind of justice, resulting in an (unconscious?) upsetting trend in Hollywood promotional material that features women being harmed as a selling point. Look at the poster for The Big Heat, which shows Bannion twisting Debby’s arm behind her back. This never occurs in the film; it is Stone who bends Debby’s arm in the film. Likewise, promotion stills show Bannion gripping Debby’s hair in an aggressive way, another scene that never occurs in the film. Moreover, any violence that transpires between Bannion and women in the film does not seem to stem from some psychopathic preoccupation, as it does Stone. When he nearly strangles Bertha, he does so out of an unbridled moment of vengeance-fuelled hate, which he suppresses and controls. It is his ability to suppress impulses through his morality that differentiates him from Stone. Nevertheless, Columbia’s promotional department taps into some unconscious element of the 1950s viewing audience that wanted to bring harm to women, to correct them through acts of violence.

Such concerns have been analyzed through more in-depth studies of gender roles and domestic ideologies of the 1950s; fortunately, aside from the studio’s distasteful marketing of the film, The Big Heat resists typical female tropes, not only through Katie’s unusual sexualized domesticity and Debby’s self-sacrifice, but by placing Bannion in the role of an homme fatale—the male equivalent of a femme fatale. Bannion seems to emit an aura that causes every woman he comes in contact with to die. Lucy, Katie, the widow Duncan, and Debby all perish due to their association with Bannion, though none of them by his hands. When Bannion first investigates Duncan’s suicide, he worries about facing corrupt officials and Lagana. But Katie tells him to “go ahead and lead with your chin.” In doing so, his actions inadvertently lead to Katie’s death. Or, when he talks to Debby in a conversation that she instigates, it gets her scalded. Later, he confides in Debby, explaining that he could not bring himself to kill the widow Duncan, and so Debby chooses to do it for him, without Bannion’s knowledge. And while several film scholars have suggested that Bannion secretly hoped Debby would murder the widow, nothing onscreen suggests such conniving on his part. Quite the opposite. Bannion remains so blinded by his drive for justice and inner moral conflict that fate seems to take over, and because of this, he inverts the femme fatale trope into an homme fatale through a series of deaths by association.

Such concerns have been analyzed through more in-depth studies of gender roles and domestic ideologies of the 1950s; fortunately, aside from the studio’s distasteful marketing of the film, The Big Heat resists typical female tropes, not only through Katie’s unusual sexualized domesticity and Debby’s self-sacrifice, but by placing Bannion in the role of an homme fatale—the male equivalent of a femme fatale. Bannion seems to emit an aura that causes every woman he comes in contact with to die. Lucy, Katie, the widow Duncan, and Debby all perish due to their association with Bannion, though none of them by his hands. When Bannion first investigates Duncan’s suicide, he worries about facing corrupt officials and Lagana. But Katie tells him to “go ahead and lead with your chin.” In doing so, his actions inadvertently lead to Katie’s death. Or, when he talks to Debby in a conversation that she instigates, it gets her scalded. Later, he confides in Debby, explaining that he could not bring himself to kill the widow Duncan, and so Debby chooses to do it for him, without Bannion’s knowledge. And while several film scholars have suggested that Bannion secretly hoped Debby would murder the widow, nothing onscreen suggests such conniving on his part. Quite the opposite. Bannion remains so blinded by his drive for justice and inner moral conflict that fate seems to take over, and because of this, he inverts the femme fatale trope into an homme fatale through a series of deaths by association.

Though the film’s final line, where Bannion tells an office gopher to keep the coffee hot, threatens to trivialize what came before, the lasting message suggests unchecked corruption and crime demand that someone fight them. Rather than a standard film noir’s scheming detective who embraces crime and vigilantism to satiate his impulses, Bannion grapples with morality and how to enforce it. Lang makes Bannion’s mission ever more confronting by pitting him against an intractable desecration of American values, backed by a monstrous degree of violence and bloodshed. And the film’s impact has only sharpened since its release. When The Big Heat was inducted into the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry for future preservation in 2011, the official release called it, “One of the great post-war noir films” and said “its subtly expressive technique and resistance to formulaic denouement, manages to be both stylized and brutally realistic, a signature of its director Fritz Lang.” To be sure, the film was written, produced, and directed in a classic Hollywood tradition; however, the sheer force of the storytelling makes everything seem more visceral than classic Hollywood would allow. The visceral feeling derives from Lang’s recurring, cynical view that the world is a punishing, unforgiving place, and so a person must find their own meaning within the chaos. The film remains characterized by its unique combination of Bannion’s moral integrity and the vile, primitive violence in the film, a balance which is inherently Langian.

Bibliography:

Bogdanovich, Peter. Fritz Lang in America. Studio Vista, 1967.

Bogdanovich, Peter. Who the Devil Made It: Conversations with Legendary Film Directors. Alfred A. Knopf, 1997.

Bordwell, David, et al. The Classical Hollywood Cinema. Columbia University Press, 1985.

Jenkins, Steve, editor. Fritz Lang: The Image and the Look. BFI Publishing, 1981.

Jewell, Richard B. The Golden Age of Cinema: Hollywood 1925-1945. Blackwell Publishing, 2007.

Leblanc, Gérard and Brigitte Devismes. Le Double Scénario chez Fritz Lang. Armand Colin, 1991.

“Martin Scorsese on The Big Heat.” Dir. Fritz Lang. 1953. Blu-ray. Twilight Time, 2016.

McArthur, Colin. The Big Heat. British Film Institute Film Classics, BFI Publishing, 1992.

McGilligan, Patrick. Fritz Lang: The Nature of the Beast. St. Martin’s Press, 1997.

Place, Janey. “Women in Film Noir.” Women in Film Noir. Edited by E. Ann Kaplan. British Film Institute, 2000. pp. 47-68

Truffaut, François. “Règlement de comptes (Fritz Lang).” Cahier du cinéma. Vol. 32. Feb. 1954.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review