The Definitives

The Big Country

Essay by Brian Eggert |

In The Big Country, Gregory Peck plays Jim McKay, a former sea captain who retires from his family’s shipping business to marry and settle down on the Western frontier. Unlike the generic gunslingers and outlaws who usually headline the genre, Jim offers a thoughtful and pacifist alternative: a hero with nothing to prove except to himself. When he first arrives at the Terrill ranch, the resident foreman, Steve Leech, played by a swaggering Charlton Heston, tries to put Jim atop Old Thunder, an untamable stallion. Jim sees through the hazing ritual. “Some other time,” he says, declining the offer, much to the disappointment of onlookers. Only later, with no one watching, does Jim attempt to ride Old Thunder. The animal bucks him to the ground, repeatedly; but each time, Jim dusts himself off and tries again. His resolve soon breaks the horse in a victory that Jim reserves for himself and a single ranchhand sworn to secrecy. In a similar scene, the growing tension between Jim and Steve finally reaches a head. Yet Jim refuses to brawl in front of spectators, even if his fiancée believes his refusal shows his cowardice. Not until the early morning does Jim return to Steve and agree to a private fight. The two men pummel each other to a standstill. Their faces bruised and bloody, Jim asks, “Now, what did we prove?” In both cases, The Big Country questions the modes of Western braggadocio, preferring a more contemplative approach to solving problems than the usual duels and fisticuffs.

William Wyler’s 1958 picture contains no strict sense of loyalty or adherence to the violent codes of the Western. It breaks from the traditional genre framework to approach it from an outsider’s perspective, signaling itself as something altogether different from its first moments. Although it opens with sepia-toned images of a stagecoach riding the open terrain—set to Jerome Moross’ iconic score, one of the best ever written for a Western—this otherwise classical image that evokes the Western films of the past leads into an unconventional hero’s introduction. The stagecoach delivers Jim to his destination, a small town in the middle of rolling hills, and he emerges in a derby hat and clean suit. He carries no gun and has no familiarity with the territory; he has no need for them. Armed with a map and compass, and the education to use them, Jim’s virtue approaches that of Peck’s role as Atticus Finch four years later in To Kill a Mockingbird. Jim’s pensive, rational, non-confrontational personality may seem out of place in the Wild West, and indeed the Western genre, but his onscreen presence forces the viewer to stand back with him and reflect on the story that progresses. Though he arrives to marry the daughter of a well-known rancher, he finds himself in the middle of a feud rivaling the Hatfields and McCoys. Seeing the conflict boil over with his own eyes, the usual trappings of a Western—the macho grandstanding, the desperate need to prove oneself, and the violence used to solve petty land disputes—seem almost comically absurd. It’s a film whose protagonist watches a Western unfold with a critical eye.

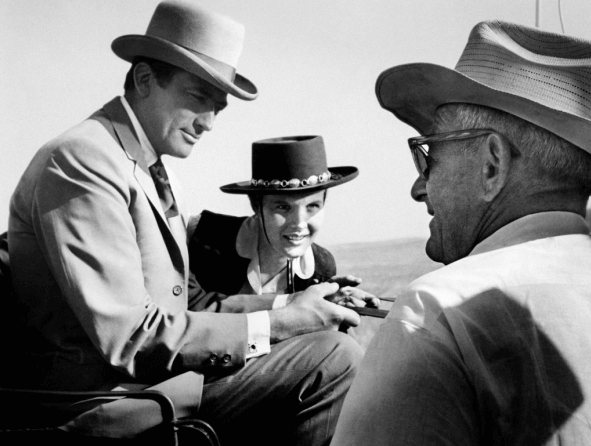

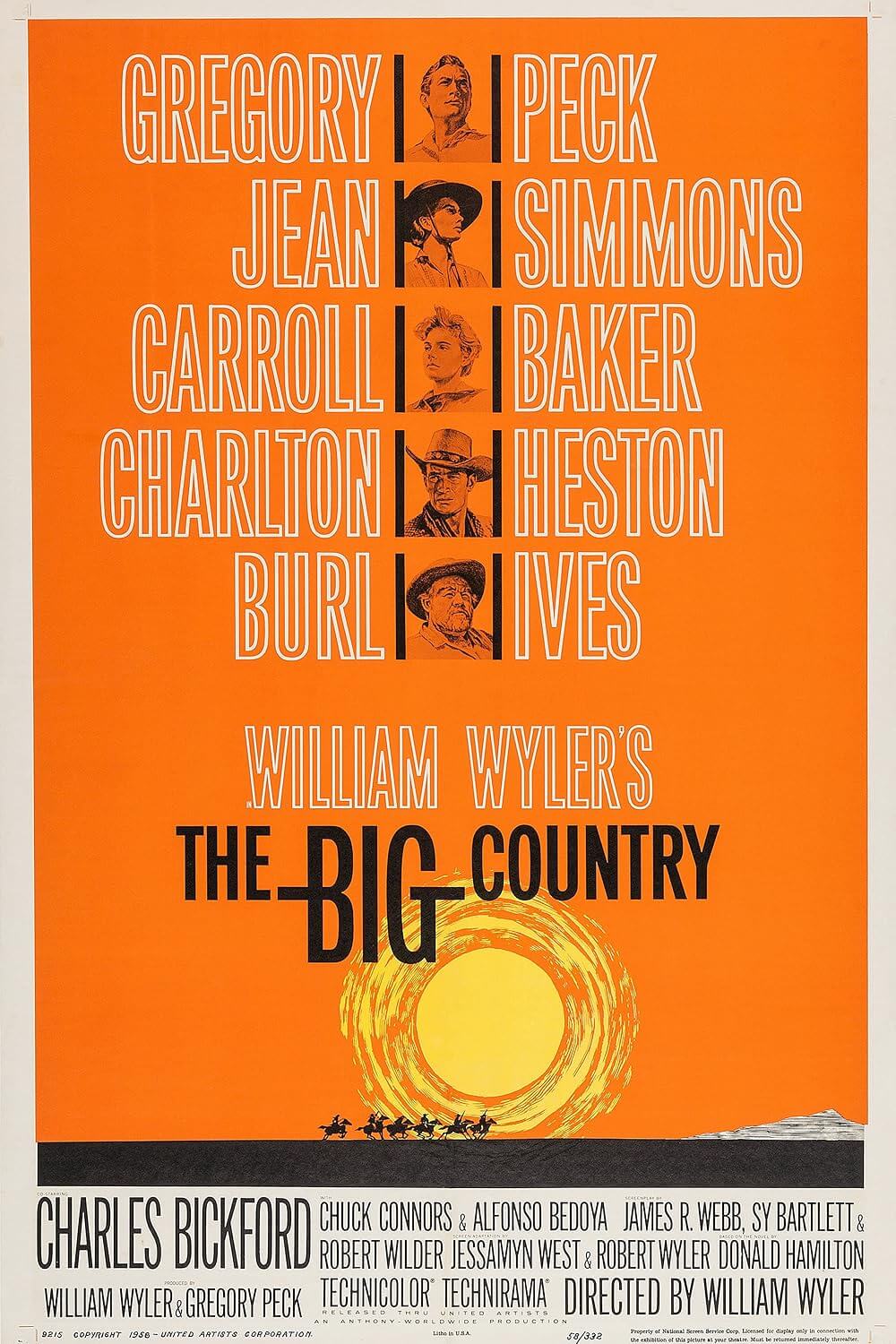

The production started with Peck, who had worked and become close with Wyler on Roman Holiday (1953). He brought the director Donald Hamilton’s book, which was originally serialized under the name “Ambush at Blanco Canyon” in the Saturday Evening Post. Hamilton was a well-established author of Westerns, and he would go on to write traditionalist scripts like How the West was Won (1962) and genre reinterpretations like Cheyenne Autumn (1964). The book, titled The Big Country, contains Hamilton’s revisionist streak. Peck recognized its “anti-macho” appeal and, along with Wyler, developed the picture under United Artists, though each man formed his own production company to handle separate responsibilities. Wyler’s World Wide Production made the artistic decisions, while Peck’s Anthony Productions, named for his newborn son, oversaw the casting and final script approval. Peck also had a cattle business and personally supervised the ranching aspects of the production, including the selection of horses and wranglers. The screenplay proved to be a problem, however, requiring the writer’s guild to resolve some tensions about who received credit. Ultimately, the names of five credited writers would appear on-screen, not including Hamilton, who supplied the initial draft despite having no experience writing screenplays. United Artists gave Wyler a $2.8 million budget, and filming lasted four months, starting in July 1958, on location in the Mojave Desert, at Red Rock Canyon, and at the makeshift town built by the production. Even though Peck worked closely with the various writers on the production, he remained unsatisfied with the shooting script, which continued to change as the troubled shoot progressed.

The story follows Jim, who arrives from the East Coast with plans to marry Patricia Terrill (Carroll Baker). Her family lives on an expansive ranch owned by her father Henry, known as The Major (Charles Bickford). The Terrills have a longstanding feud with the Hannasseys, a rough bunch living in Blanco Canyon under the leadership of their patriarch, Rufus (Burl Ives). Both families depend on the Big Muddy, a winding river that offers the only water for miles, to support their cattle. But the river snakes through a lush piece of land owned by Julie Maragon (Jean Simmons), the local schoolmarm. Honoring her grandfather’s wishes, Julie will gladly allow both the Terrills and Hannasseys access, except that the Major and Rufus have a mutual hatred—going back so far, it’s doubtful either man remembers what started their conflict. Terrill, a “high-toned skunk,” claims he will bring civilization to the West with his fancy home full of chandeliers and imported furniture, where he holds elegant parties and puts on an air of sophistication to mask his cruelty. His daughter, Patricia, has an outwardly ladylike appearance, and while her family’s East Coast values seem to represent a touch of class, they prove downright savage when it comes to the Big Muddy. The Hannasseys, meanwhile, poor and living in wooden shacks, dress like gnarled cowboys. Rufus’ boys, headed by the aggressive Buck (Chuck Connors), drink and cause a ruckus in town and on frontier roads. Buck sniffs after Julie, and his method of courtship extends from home invasion to attempted rape. Despite his unruly children, Rufus has a sense of honor and dignity. But with the nearest law some 200 miles away, the land dispute escalates after Jim’s arrival.

Jim’s intention of marrying Patricia quickly comes into question when he clashes with the Major, as well as the Terrills’ top foreman, Steve Leech, who makes no attempt to hide his love for Patricia and hatred of Jim’s cultivated demeanor. As a gentleman, Jim does not meet the territory’s virile standards, where men like Leech and the Major use violence to prove their courage, property lines, and sense of self. “Here in the West,” the Major explains, “a man is expected to defend himself.” But time and again, Jim refuses to resort to anger and violence to prove his bravery and manliness to Patricia, who idolizes her father to a disturbing degree. At a party in her fiancé’s honor, she declares her father the most handsome man in attendance and tells Jim that she could never move away because she “couldn’t stand being away” from the Major. Incestuous undertones aside, Patricia doubts Jim’s mettle when he questions the Major’s attack on the Hannasseys, declines Leech’s offer to ride Old Thunder, and dismisses Leech’s many attempts to start a fight. Patricia wants to be fought over (“How many times does a man have to win you?” Julie asks her friend at one point), and so she fails to recognize or appreciate Jim’s intelligence and control. In one sequence that finds Jim away for days, exploring the vast plains on a horse, Patricia forgets that, as a sea captain, he needs only a map and compass to find his way. And being a modest man whose sense of honor comes from within, his proposed marriage to Patricia collapses when she demands that Jim conform to the West’s code of violence.

The Big Country’s rearrangement of classical Western themes remains subtle, stemming from the Terrill-Hannassey conflict and Jim McKay’s worldview. At first, Wyler’s film feels situated in a familiar setting where every “good morning” is answered with a “howdy,” and every “howdy” receives a “good morning.” Stories similar to the film’s central conflict between the Terrills and Hannasseys could, and have, been the foundation of countless Westerns about land disputes and family feuds. But in a more standardized setup, the backwoods Hannasseys would have been the villains and the modern Terrills would have been the heroes who bring civilization to the Wild West. Consider John Ford’s My Darling Clementine (1948), where the civilizing Earps run the rugged Clantons out of Tombstone, creating a safe place for the schoolmarm. Instead, both families in The Big Country, seen from Jim’s critical vantage point, a view marked by Peck’s expressions of quiet observation and silent judgment, have a limited perspective. The Terrills consider themselves morally superior, but their violent attacks—they ride into the Hannassey camp, invade their homes, scare off their horses, and shoot holes in their water supply—reveal hypocrisy in their selfish campaign to keep the Hannasseys away from the Big Muddy. Rufus Hannassey, though decidedly more honorable, answers the Major’s prompts with violence. Still, Rufus fails to control Buck, an unsavory bully and sexual predator who gives the Hannasseys a bad reputation. But as Jim observes, “This is nothing more than a personal feud between two selfish, ruthless, vicious old men”—notably, both stubborn, opinionated single fathers who raise contemptible children.

While the standard Western characters in The Big Country amount to reprehensible and treacherous men fighting over access to the Big Muddy, Jim’s conception of the world goes beyond this few thousand acres of grassland. He does not aggrandize the land in the same manner as locals, who regularly mention what a “big country” they inhabit. “Y’ever seen something s’big?” one man asks him. “Well, yes,” Jim replies, “a couple of oceans.” Unaffected by the mythical promise of Manifest Destiny, Jim sees the land for what it is, a natural wonder to be appreciated and cultivated. He sees beyond the problems of the Terrills and Hannasseys, and he hopes to live a peaceful life on the Big Muddy, which he arranges to buy from Julie—a well-educated romantic alternative to Patricia. But when the Terrills block the Hannasseys from accessing the Big Muddy, Rufus orders Buck, who lies when he claims to have a connection with Julie, to bring her to Blanco Canyon and marry her, at which point he will control her land. Meanwhile, the Terrills plan a raiding party to rescue Julie. But Jim rides into Blanco Canyon unarmed, accompanied only by Ramón (Alfonso Bedoya), a trusted ranchhand, to negotiate her release. Rufus recognizes Jim as a gentleman, and what’s more, sees that he loves Julie—he also finally sees his son’s dishonorable character in action when Buck attempts to cheat in a gentleman’s duel with Jim, requiring Rufus to commit filicide. The conflict finally resolves itself when the Major and Rufus meet in Blanco Canyon and kill each other in a face-to-face shootout, leaving Jim and Julie to ride back to the Big Muddy.

Though The Big Country is among the greatest Westerns, its director, William Wyler, is not a name synonymous with the genre like those of John Ford, Anthony Mann, or Budd Boetticher. Born in Alsace-Lorraine in 1902, Wyler studied business and the clothing industry in Europe, though none of his brief careers clicked until his mother asked her cousin, Carl Laemmle, the head of Universal Pictures, to give her son a job. Laemmle had given Irving Thalberg and Harry Cohn their start; he would do the same for Wyler as well. Wyler started in Universal’s New York offices as a gopher, translating bits of news and celebrity hype for French and German film magazines. He eventually transferred to Tinsel Town, where he apprenticed under directors such as Jack Conway. It didn’t take long for Wyler to settle on a career in directing. His first jobs were two-reeler Westerns on the studio backlot, beginning with The Crook Buster in 1925, followed by an additional two-reeler every week. These were simplistic stories filled with white-clad heroes, dastardly villains, damsels in distress, chases on horseback, and daring shootouts. “They were all very elementary stories,” Wyler recalled for historian Kevin Brownlow. “They’d start with action, finish with action and have some action in the middle.” Over the next several years, Wyler made two-dozen short Westerns for Universal before graduating to more substantial productions with big-name stars.

In a matter of years, Wyler would become one of the most respected and acclaimed directors of Hollywood’s Golden Age. He remained at Universal until 1935, when he signed with independent producer Samuel Goldwyn. While under Goldwyn, he expanded his repertoire into other genres, from prestigious literary adaptations (Dodsworth, 1936) to gritty crime stories (Dead End, 1937) to Oscar-winners (Mrs. Miniver, 1942). He became one of the most respected of all directors during the era, and his films were nominated for, and won, dozens of Academy Awards. Over his forty-five-year career, he earned three Oscars for Best Director. Wyler’s reputation was “only slightly exaggerated as a man who couldn’t make a flop,” noted biographer Jan Herman. By the time he made The Big Country, however, almost two decades had passed since Wyler had ventured into the Wild West. His last film in the genre, The Westerner from 1940, featured Gary Cooper in a thrilling conflict with Walter Brennan’s cruel iteration of Judge Roy Bean. Despite Wyler’s vast experience in the genre, followed by a long line of “A” productions in Hollywood, The Big Country was among the well-established filmmaker’s most tempestuous outings behind the camera.

Though Wyler’s standing was enough to convince Heston to downgrade himself into a supporting role, regardless of solidifying his leading man status with The Ten Commandments (1956), Wyler’s directing style had a distinct reputation. Herman noted that he was thought to be “too slow, too deliberate, too careful, too demanding and, consequently, for tending to run over schedule and over budget.” Wyler was also known for demanding multiple takes of a given scene, earning him the nickname “40 Take Wyler,” much to the dismay of several actors. Bickford walked off the set in a huff, cursing all the way to his trailer after Wyler demanded nineteen takes of a particular scene. Wyler’s assistant director, Robert Swink, had to convince Bickford to return, at which point the director shot another eight takes. Shooting on location in the punishing heat, with few of the accommodations usually granted actors on the set of a Hollywood motion picture, certainly did not help matters. Simmons refused to discuss the production for years afterward. Baker clashed with Wyler and tried to tell him how directors are supposed to behave. Peck stomped off the set, abandoning the production for several days over an issue of reshoots. It’s inevitable that more than one historian has compared the mood on the set to the conflict between the Terrills and Hannasseys. In an interview about The Big Country, Ives suggested that Wyler used the uncomfortable situation to get the most out of performers. “Willy had all kinds of tricks to get that picture down.” But then, Ives and Heston were among the only cast members who got along with Wyler. “He was enigmatic sometimes,” Ives said, “but that’s what he did to make me figure things out.”

Even so, Wyler’s approach, combined with the script challenges and usual obstacles of an on-location shoot, ran the picture’s budget up to $4 million, making it nearly impossible for the production to earn a sizable profit. Moreover, some of the credit for the end result—including the scoring, cutting, and final scene—belongs to Swink, who had worked alongside Wyler on his previous five films. A few months before the production wrapped, Wyler announced he was leaving for Rome to begin production on Ben-Hur. He gave Swink the authority to complete the picture, which Swink did, and he approved of the final cut in a letter to his assistant: “I can’t begin to tell you how pleased I am with the new ending… The shots [you] made are complete perfection. Exactly what was needed.” But The Big Country is not without a few curious, awkward moments. Consider a scene near the finale in which Steve, increasingly tested by the Major’s stubbornness and sliding ethics, stands up to his boss and refuses to follow him into Blanco Canyon. Steve seems to redeem himself after having blindly followed orders throughout the film, until, in the next instant, after the Major has gone in alone, Steve follows. Moross’ music, misused in this scene where the Major bull-headedly marches on, sounds triumphant and in direct conflict to the mood of Steve’s personal victory. Fortunately, in other scenes, The Big Country refuses to romanticize violence with Moross’ score—the bout between Jim and Steve, as well as the face-off between the Major and Rufus Hannassey, proceed without a score, as if to present these violent ends without idealization.

The Big Country premiered in October 1958 and received a mixed reaction from critics of the period, many of whom had gotten wind of the high-tempered production and projected evidence of the troubles in their reviews. In an otherwise lukewarm assessment, Bosley Crowther’s review in The New York Times called the film “mighty pretentious” given its size and nearly three-hour runtime. The critic in Variety wrote the story was “dwarfed by the scenic outpourings,” and the Western storytelling was merely “serviceable.” Nevertheless, audiences enjoyed the picture, which earned an Oscar nomination for Moross’ rousing score and Ives a deserved statue for Best Supporting Actor. The film belongs to a group of Westerns released in the 1950s that sought to compete with the growing tide of television viewership in America, where Western shows like Gunsmoke, The Gene Autry Show, Wagon Train, and countless others dominated airtime. Using a widescreen frame and panoramic imagery photographed by Franz F. Planer to emphasize the grandeur implied by the title, Wyler sought to make a large-scale, crowd-pleasing Western that would reduce anything airing on television screens to second-rate material. And along with the sheer grandeur of the production, Wyler’s visual approach offers an unexpected critique of typical Western yarns. Watch the way he uses wide lenses and distanced shots to reduce his characters to mere specs in the widescreen frame, particularly in the film’s duels, making them seem meaningless in the grand scheme of things—it’s a bold contrast to the extreme close-ups of Sergio Leone (Once Upon a Time in the West, 1968) that give the viewer an intimate relationship with Western violence.

Both Wyler and Peck may have hoped for commercial success more than awards recognition, but Wyler’s interest in the material revolved around its portrayal of “a man’s refusal to act according to accepted standards of behavior” in a Western. Many filmmakers questioned the genre’s conventions during the 1950s, raising issues of racism and psychological complexity that went against the simple stories of law versus order and good versus evil, which prevailed when Wyler first arrived in Hollywood. In The Big Country, Wyler liked how “Customs of the Old West were sort of debunked.” Filmmakers such as Anthony Mann (The Naked Spur, 1953; Man of the West, 1958), Nicholas Ray (Johnny Guitar, 1954), and Samuel Fuller (Forty Guns, 1957) sought to acknowledge that Western heroes had been mythologized out of a more equivocal history. Four years after Wyler’s film, Ford made The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, a film that acknowledges the way Western myths rarely have a basis in fact with the line, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” But Wyler’s film is more interested in the fact than the legend, and like Jim McKay, he seems drawn more to the splendors of Nature than the people inhabiting it. Wyler identifies with Jim, watching patiently, from a distance, as other Western characters fight over land and destroy each other. William Wyler and Jim McKay are observers who have seen the world and violence in various forms, and from their perspective, the Western conflict seems foolish.

Although Wyler was widely celebrated during his heyday, auteur theorists later skewered him next to filmmakers like Ray, Howard Hawks, and Alfred Hitchcock. These filmmakers have clear visual and thematic preoccupations that could be charted throughout their careers, and therefore, according to the hardened auteurist critics writing in the film magazine Cahiers du cinéma, Wyler’s output did not meet the standards of personalized filmmaking that defined auteurism. The American counterpart to the French critics, Andrew Sarris, who popularized the Auteur Theory in academic circles, wrote of Wyler’s work in his book The American Cinema: Directors and Directions: 1929-1968, in a chapter called “Less Than Meets the Eye.” He called Wyler’s career “a cipher as far as personal direction is concerned.” Elsewhere, Herman notes that Wyler was seen as a corporate filmmaker because he made commercial successes, but films like The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), a passion project that echoes Wyler’s own experiences as a World War II veteran struggling to adjust in postwar America, and The Big Country, which reflects Wyler’s humanist attitude and criticism of violence, demonstrate the filmmaker’s personal influence over his work.

The Big Country could be mistaken for a typical Western, except Wyler’s direction emphasizes the story’s theme about the irrationality of violence. He luxuriates in the vast landscape and scenery to minimize the petty struggles between the Terrills and Hannasseys, leaving the viewer with a sense that their land disputes and personal squabbles are insignificant to the size and power of Nature. The approach turns The Big Country into a rare epic Western that aligns with the outlook of Jim McKay, about whom Ramón says, “A man like him is very rare.” Wyler forces the viewer to watch a Western play out through Jim’s eyes. He is hopeful for mutual understanding and negotiation rather than violence, and he looks on from a critical perspective when the Terrills and Hannasseys destroy themselves in a senseless showdown. When the two patriarchs have killed each other in the end, Jim gives Steve a look that says, “Now what did we prove?” The Big Country suggests that, when faced with a resolute enemy, you can either keep fighting until one or both of you is dead, or you can recognize that violence solves nothing and stop yourself before it’s too late.

(Note: This essay was suggested and commissioned on Patreon. Thank you, Rose, for your continued support!)

Bibliography:

Herman, Jan. A Talent for Trouble: The Life of Hollywood’s Most Acclaimed Director, William Wyler. Phantom Outlaw Editions, 2015.

Kitses, Jim. Horizons West: Directing the Western from John Ford to Clint Eastwood. British Film Institute; 2Rev Ed edition, 2008.

Miller, Gabriel. William Wyler: The Life and Films of Hollywood’s Most Celebrated Director. The University Press of Kentucky, 2013.

Sarris, Andrew. The American Cinema: Directors and Directions: 1929-1968. Dutton, 1968.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review