The Definitives

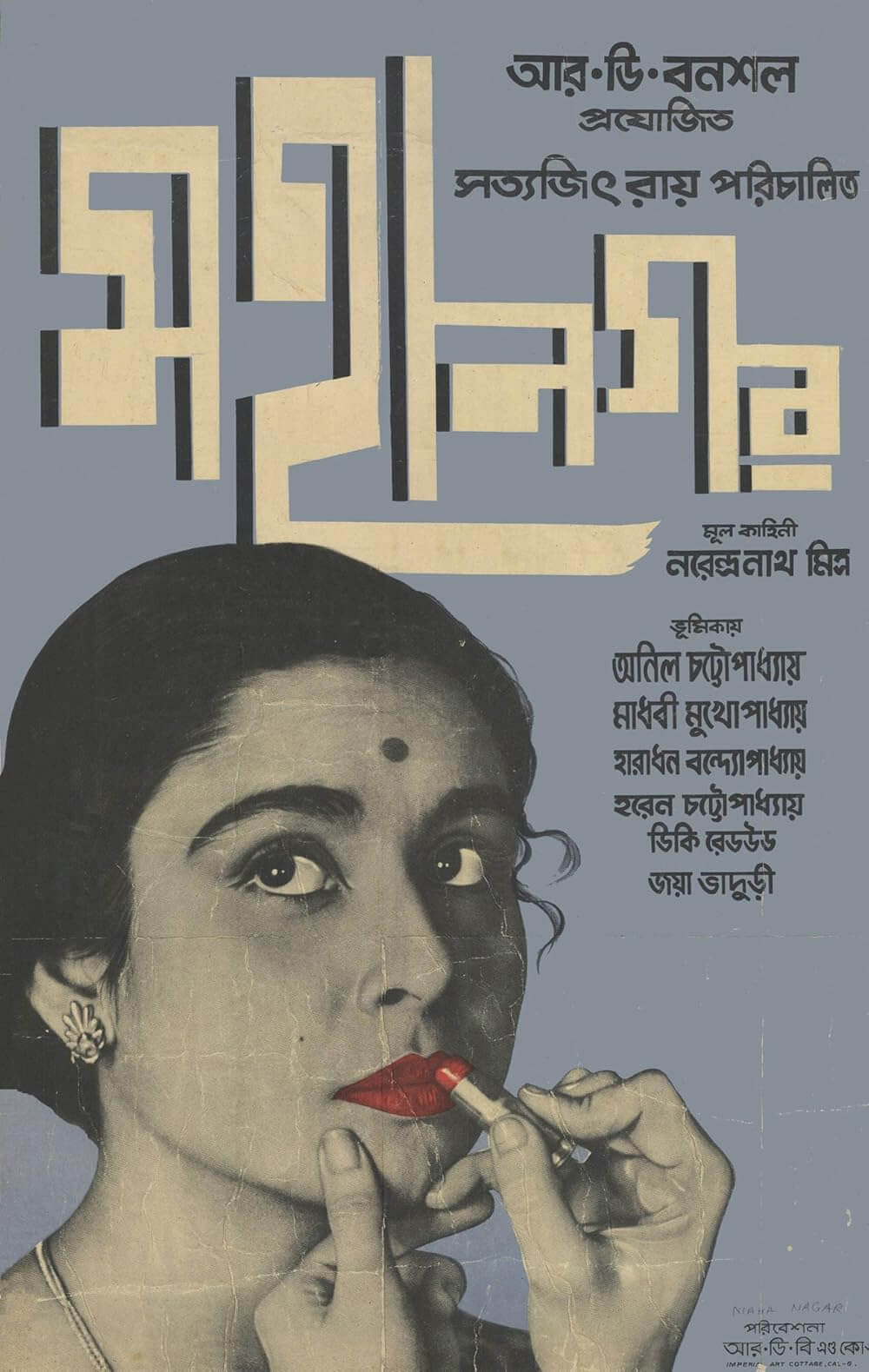

The Big City

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Satyajit Ray’s The Big City (Mahanagar, 1963) explores the specificity of human subjects in their world, the lower-middle-class sections of what is today Kolkata. The story is, on the surface, a simple one that reflects the contemporary struggles of an average family. A housewife decides to work and provide a supplementary income, a rare occurrence among traditional Bengali joint families in 1955 when the film takes place, and her decision causes a conflict within the otherwise traditional family dynamic. More than a portrait of a valorized woman in contemporary India, her journey from an objectified figure in a domestic household role emerges into one of symbolic feminine subjectivity, which itself becomes an emblem of the cultural discord between tradition and modernity. The role of women in the urban world often dominated discussions of twentieth-century cultural politics in India, and Ray’s film captures the social relations dominant in the post-independence period after the end of British rule, where time-honored values came into question. However, through its observations on the family and workplace in pseudo-realist fashion, The Big City supplies both a feminist statement and a political condemnation. Ray’s representation of a woman’s desire for self-actualization, while an avowal of his personally informed gender politics, also results in a critique of the dehumanizing effect of the new corporate presence, introduced with patriarchal capitalism, on Bengali culture.

Ray based his film on two short stories by Narendranath Mitra, and the title of the first, “Abataranika” (1949), as scholar Keya Ganguly observes, means an introduction or preface. Much of the original story takes place before Arati, an undereducated housewife, begins a career as a door-to-door salesperson, and so the title infers her evolution into a fully realized subject by the story’s conclusion. While the word “abataranika” defines a beginning, Ganguly notes that its origins in Sanskrit infer the commencement of a descent into a lower status, which suggests that Arati’s growth into a woman of some agency also contains a loss or sacrifice of sorts. Though Arati realizes her ambition of helping her husband, Subrata, with their family’s financial needs, the journey will not be effortless and, what is more, it will lead to a certain disenchantment and harsh reality. Ray carries this dialectical theme into his film, where Arati’s personal validation is resolved, while the reality of her situation is such that she descends from the comfortable position as a housewife into that of a worker, who faces the struggle to secure a job and, afterward, is confronted by the moral and ethical ambiguities introduced by capitalism. As a working woman, she also faces resentment from her child and in-laws for betraying tradition. Beyond Mitra’s influence, Ray’s identity feeds this subject matter, coming from a family rooted in the social justice and feminist ideals that sought to refract outdated aspects of culture through a humanist lens. His approach to cinema, both in theme and form, was inextricable from his upbringing and sociopolitical views, which inform The Big City.

Ray comes from a line of culturally progressive and influential artists, professors, innovators, and thinkers. As biographer Andrew Robinson revealed, Ray’s family believed secretly that their creative streak originated with a mystical origin, allowing their family members premonitions and artistic inspiration that science could not explain. His family members belonged to the Brahmo Samaj, or Brahmos, a group that emerged in the 1820s as reformist social justice movement that valued ideas of democracy and feminism, and further, adopted English practices and techniques to adequately address social, intellectual, and political issues of the day, including the English intrusion on their culture. Ray’s grandfather, Upendrakisore Ray, pioneered a halftone printing process, authored songs in Hindi, dabbled in astronomy, and wrote poetry and children’s books. Sukumar Ray, Satyajit’s fantasist father, studied printing, wrote children’s stories in a surreal and nonsensical style, and also shared what would become his son’s interests in photography and cinema. Both his grandfather and father followed the Brahmos lifestyle. They drew influences from the West and applied them to their devotion to the East, such as Sakumar’s paintings in the style of illustrations that appeared in Lewis Carroll texts, or Upendrakisore’s interest in innovating British printing methods to produce distinctly Indian works. Although Sukumar, like his father, was independent and patriotic but not rebellious or political, they supported the Brahmos movement throughout Bengal and became increasingly skeptical of British imperialism.

Ray comes from a line of culturally progressive and influential artists, professors, innovators, and thinkers. As biographer Andrew Robinson revealed, Ray’s family believed secretly that their creative streak originated with a mystical origin, allowing their family members premonitions and artistic inspiration that science could not explain. His family members belonged to the Brahmo Samaj, or Brahmos, a group that emerged in the 1820s as reformist social justice movement that valued ideas of democracy and feminism, and further, adopted English practices and techniques to adequately address social, intellectual, and political issues of the day, including the English intrusion on their culture. Ray’s grandfather, Upendrakisore Ray, pioneered a halftone printing process, authored songs in Hindi, dabbled in astronomy, and wrote poetry and children’s books. Sukumar Ray, Satyajit’s fantasist father, studied printing, wrote children’s stories in a surreal and nonsensical style, and also shared what would become his son’s interests in photography and cinema. Both his grandfather and father followed the Brahmos lifestyle. They drew influences from the West and applied them to their devotion to the East, such as Sakumar’s paintings in the style of illustrations that appeared in Lewis Carroll texts, or Upendrakisore’s interest in innovating British printing methods to produce distinctly Indian works. Although Sukumar, like his father, was independent and patriotic but not rebellious or political, they supported the Brahmos movement throughout Bengal and became increasingly skeptical of British imperialism.

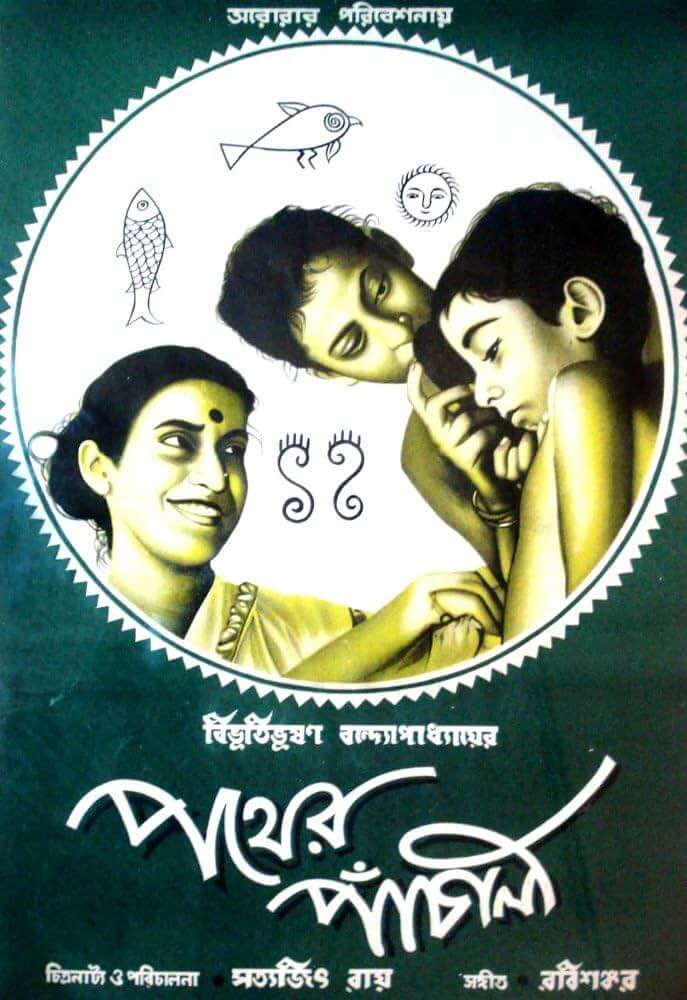

Ray was born in Calcutta in 1921, and he embraced the Brahmos ideology advocated by his family of creatives. He grew up hardly knowing his father, who died prematurely in 1923. Without a father to support them, Ray’s mother constantly worked, recalling the mother from Ray’s Apu Trilogy, or later, Arati from The Big City. He remained bound to urban living in Kolkata and oblivious of the country lifestyle, making village life something he would have to research much later in his career for Pather Panchali (1955). As a child, he was known to sit and observe the people around him. Robinson called it “imbibing” life. Ray later wrote an autobiographical account of his childhood experiences called When I Was Small in 1981, filling the pages with his lively drawings, accounts of the cinema, and stories about family and friends. At a young age, Ray explored his love of music from both the East and the West, a love he later considered stronger than his affection for cinema; he spent much of his time in college listening to music, though he did not learn to play an instrument until adulthood. He earned a degree in Economics from Calcutta University, but after graduating in 1939, he was unsure about his future and dreamt of becoming a painter.

Ray’s mother encouraged him to attend Rabindranath Tagore’s pastoral University of Santiniketan, a countryside “Abode of Peace” designed to cleanse the mind and body, although Ray was hesitant to take advantage of his family’s longstanding relationship with the famed Tagore for fear of becoming another unflinching devotee. Santiniketan boasted instructors from the East and West, and Ray could freely explore his interests in painting, literature, and music appreciation in his more than two years there, before abandoning the five-year course for a career in the commercial art of advertising. Despite having a Western approach to narrative and formal structures in his films, Ray’s greatest influencer remains Tagore (1861-1941), whose formative presence in the Bengal Renaissance sought a blend between Eastern and Western values and religious clarity, and from this mixture, a balance. A friend of the Ray family, Tagore was an incredibly talented and renowned poet, dramatist, essayist, painter, songwriter, educator, philosopher, composer, and Nobel Prize-winning novelist—whom Ray himself considered more talented and versatile than William Shakespeare. Though Ray studied under Tagore for only a brief time, Tagore’s work provided Ray’s films with references and source material that many Westerners otherwise unfamiliar with Tagore may never notice. Ray’s films based on Tagore’s stories, from Charulata (1964) to The Home and the World (1984), would make Tagore and Ray inextricably linked in the eyes of Bengali viewers. Even so, the class of Tagore’s reformation was aristocratic and, throughout Ray’s career, as the director relied on that class for artistic influence, he also critiqued its occasional elitist ignorance and lack of compassion.

While exploring art under Tagore at Santiniketan, and on his own during this formative part of his young life, Ray began to distinguish the differences between the art of the East and West. He characterized Eastern art as “a sort of symbolism and a looking for the essence rather than the surface,” while Western art had a circumscribed and individualized quality. He continued to take in classical and modern music from the East and West, celebrating Bach, Beethoven, and Ravi Shankar with equal fascination. During this time, Ray also pursued his interest in film and theory, forming the Calcutta Film Society in 1946, several years before he made his first motion picture. His group formed the inaccurate reputation of elitist and snobbish critics who focused their energies on discrediting Indian motion pictures in favor of films from other countries, particularly the West. Still, watching films was a challenge, as the Indian Cinematograph Act of 1918 applied its censorship rules to gatherings of any size, a restriction that required Ray’s Film Society to seek out screenings at foreign embassies where the Act did not apply. Over time, Ray soon realized he was incapable of becoming a great painter and combined his two college disciplines, Economics and Fine Art, into the natural medium of advertising, where he spent ten years of his adult life—until 1956, when he left following his directorial debut on Pather Panchali.

While exploring art under Tagore at Santiniketan, and on his own during this formative part of his young life, Ray began to distinguish the differences between the art of the East and West. He characterized Eastern art as “a sort of symbolism and a looking for the essence rather than the surface,” while Western art had a circumscribed and individualized quality. He continued to take in classical and modern music from the East and West, celebrating Bach, Beethoven, and Ravi Shankar with equal fascination. During this time, Ray also pursued his interest in film and theory, forming the Calcutta Film Society in 1946, several years before he made his first motion picture. His group formed the inaccurate reputation of elitist and snobbish critics who focused their energies on discrediting Indian motion pictures in favor of films from other countries, particularly the West. Still, watching films was a challenge, as the Indian Cinematograph Act of 1918 applied its censorship rules to gatherings of any size, a restriction that required Ray’s Film Society to seek out screenings at foreign embassies where the Act did not apply. Over time, Ray soon realized he was incapable of becoming a great painter and combined his two college disciplines, Economics and Fine Art, into the natural medium of advertising, where he spent ten years of his adult life—until 1956, when he left following his directorial debut on Pather Panchali.

Not long after his freshman effort, Ray sought to adapt Mitra’s writings into a feature film, although delays in casting and financing pushed the production back for several years. In the interim, he made some of his finest work, nine films in all, including the last two entries in his beloved Apu Trilogy, Aparajito (The Unvanquished, 1956) and Apu Sansar (The World of Apu, 1959), his drama Jalsaghar (The Music Room, 1958), and a 1961 documentary about his former instructor, Tagore. But making The Big City depended on a strong cast, and Ray began his search for the ideal Arati in 1956. Ray’s pursuit for quality performers was a constant strain, as the predominance of untrained Bengali and what was then Bombay actors saturated India’s film industry. Given the sheer size of the Industry, bad actors were all too common, as young adults often succumbed to a familial pressure to become screen performers, despite having little raw talent. Eventually, Ray found a brief muse in Madhabi Mukherjee, whose experience was minimal before the string of superb films she appeared in for Ray. After The Big City, she starred in Charulata (The Lonely Wife, 1965) and Kapurush (The Coward, 1965), portraying modern women, in midcentury Kolkata, who either struggle with outdated traditions or have moved passed them. Mukherjee’s role as Arati in The Big City articulates how Ray’s modern-day stories often focused on people who inhabit their world but remain unable to take charge of it, no matter their status.

Set in Calcutta around the mid-1950s, the film’s lower-class Mazumdar family is unable to make ends meet on the meager bank employee’s salary earned by the paterfamilias, Subrata (Anil Chatterjee). Arati and Subrata live in a joint family consisting of their young boy, Pintu (Prasenjit Sarkar); Subrata’s teenaged sister, Bani (Jaya Bhaduri), who quietly studies for school; and Subrata’s two elderly parents. His father, Priyogopal (Haren Chatterjee), was a famous instructor, now reduced to competing in local crossword puzzles for a prize. His mother, Sarojini (Sefalika Devi), shares domestic duties with Arati. Together, they live in a cramped space, sharing a handful of small rooms, barely surviving on Subrata’s income. In Bengali society when The Big City takes place, joint family life was common, but then so was the older generation’s belief that a wife should remain at home. With several generations under a single roof, traditions could easily pass between them to accommodate more cohesive living. Through this, children adopted the values and practiced behaviors of their parents, whose values would take hold as grandchildren learned from their parents and grandparents about fixed customs. Joint families often featured an invisible woman at the center, and everyone in the Mazumdar household relies on Arati, the center of gravity around which the family orbits. Although, she’s not a luminescent star that radiates a presence in her family’s solar system—her place as the family’s caretaker is wholly assumed and taken for granted.

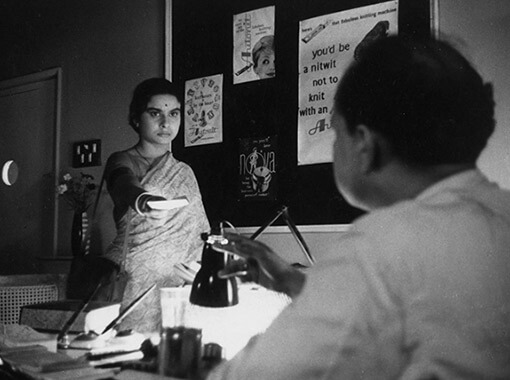

Early scenes demonstrate Arati’s routine: she prepares tea for Subrata when he arrives home from work; administers her father-in-law’s medicine; tells her mother in law what to cook, or otherwise makes the meal herself; bathes and pampers the young Pintu; and helps Bani hide her studies from her parents. One night, Subrata mentions that a friend’s wife has begun working to help their income. From that moment onward, Arati commits to the idea for herself: she wants to get a job. At first, Subrata feels wary about the decision, but he ultimately supports his wife, writing her a letter of interest and setting up an interview. Easily landing a job, Arati sets out in her new position, selling electric knitting machines to well-to-do women—a task at which she proves successful. Even so, most of the Mazumdars resent Arati for her absence from the home, including her husband, despite his initial help in securing her the job. Pintu fanes sick over his mother’s absence until he reaps the rewards of her new salary, a toy; her husband’s parents see her need to work as a personal slight—proof of their own failure to provide a better home. Though the family can now afford new, much-needed glasses for Priyogopal, he stubbornly refuses any gifts, disapproving of Arati’s affront to tradition; instead, he visits his former students to ask for help. Only Bani encourages Arati without reservation, hopeful that she will complete her studies and acquire a job. The pressure mounts, and Arati resolves to quit. But suddenly Subrata’s bank closes, and Arati must keep her job as the household’s sole earner.

Early scenes demonstrate Arati’s routine: she prepares tea for Subrata when he arrives home from work; administers her father-in-law’s medicine; tells her mother in law what to cook, or otherwise makes the meal herself; bathes and pampers the young Pintu; and helps Bani hide her studies from her parents. One night, Subrata mentions that a friend’s wife has begun working to help their income. From that moment onward, Arati commits to the idea for herself: she wants to get a job. At first, Subrata feels wary about the decision, but he ultimately supports his wife, writing her a letter of interest and setting up an interview. Easily landing a job, Arati sets out in her new position, selling electric knitting machines to well-to-do women—a task at which she proves successful. Even so, most of the Mazumdars resent Arati for her absence from the home, including her husband, despite his initial help in securing her the job. Pintu fanes sick over his mother’s absence until he reaps the rewards of her new salary, a toy; her husband’s parents see her need to work as a personal slight—proof of their own failure to provide a better home. Though the family can now afford new, much-needed glasses for Priyogopal, he stubbornly refuses any gifts, disapproving of Arati’s affront to tradition; instead, he visits his former students to ask for help. Only Bani encourages Arati without reservation, hopeful that she will complete her studies and acquire a job. The pressure mounts, and Arati resolves to quit. But suddenly Subrata’s bank closes, and Arati must keep her job as the household’s sole earner.

By the time of The Big City’s release, a large portion of Bengali culture had already moved beyond many of the concerns depicted in the film, and joint families were somewhat outdated. As younger generations and the Brahmos clashed with the predominant social values in the twentieth century, seeking an evolution of ideals, change developed for social and economic reasons. Feminism, and the activation of women in Bengali culture in all areas—familial, institutional, political, and personal—was a foundational edict of the Brahmos. Several members of Ray’s family, including his wife and mother, for example, worked in teaching roles or for the government. For families that struggled to pay bills and provide meals, allowing women to work meant the economic troubles experienced by many lower-middle-class families would be alleviated. Even so, traditionalism and orthodoxy still existed in Bengali families in 1963, and even to this day. But as Robinson points out, the film’s lasting theme resides in Arati’s role in the household, and whether she should be expected to please everyone while sacrificing her self-actualization in the process. In this sense, the larger issue of The Big City is less a topical statement about validating the economic worthiness of women in the workplace or the social order of women in Bengali society, but a person’s need for validation—even if that extends beyond their social role. Ray wanted the film’s original English-language title to be A Woman’s Place, a reference to a scene in which Subrata, in all seriousness, reminds Arati of an outmoded English saying, “A woman’s place is in the home.”

The saying, conveyed using the English language in the scene, echoes the lasting influence of British colonialism and social structures on Indian lives, predominantly through capitalism. Of course, most Ray films in contemporary settings echo the looming post-colonial influence of Westerners, as his characters often alternate between their native Hindi and English words or phrases that would be otherwise difficult to translate. The presence of the English language, along with the effects of Western influence on Bengali culture, reveal the post-colonial subjectivity of Ray’s characters. This is evidenced in the presence of Edith (Vicky Redwood), Arati’s Anglo-Indian colleague, and the racial discrimination she faces from their otherwise genial boss, Mr. Mukerjee (Haradhan Banerjee). Issues of race seldom appeared in Indian cinema at the time of The Big City’s release, since socially relevant filmmaking was a component of the alternative New Indian Cinema and not the more popular, commercial-minded Mumbai industry. But it’s Mr. Mukerjee’s racial prejudices against Anglo-Indians—that they are lazy and lack morals—which leads Arati to finally quit her job, refusing to dismiss her own moral character in the face of intolerance against her friend. Ray argues that, despite the possibilities afforded by capitalist influences on Bengali culture, the city nonetheless presents a conflict between economic security and personal contentment.

Of the ending, some have claimed that The Big City seems overly optimistic, if not unrealistically sentimental to the film’s detriment. However, such assessments overestimate the happiness of the scene. Indeed, Ray does not provide an easy solution to the workaday bourgeois lifestyle, with its moral and economic hardships. After leaving her job, Arati tells Subrata that she has quit and why, and now their household has no income whatsoever. But Arati discovers that her husband considers her actions brave and, realizing her nobility, accepts her place by his side. Together, hand-in-hand, they head into the distance to search the city for work. The scene recalls the ending of Charles Chaplin’s Modern Times (1938), where the Little Tramp and Gamine face their future penniless, but together. The implications of this final moment in The Big City are not blind confidence that Arati and Subrata will inevitably find jobs and live happily ever after. Things are more uncertain. Ray implies that personal fulfillment comes with a risk—an awareness that whatever job they find, they may face another moral injustice inherent to patriarchal capitalist systems, and thus the struggle will continue. Ray does not celebrate the modern city as a progressive, cosmopolitan place where women can realize their highest potential; he sees the modern world as a place that has taken steps to improve from outdated traditions, and has the possibility of providing a better life, but still has much growing to do before it can supply unqualified happiness.

Of the ending, some have claimed that The Big City seems overly optimistic, if not unrealistically sentimental to the film’s detriment. However, such assessments overestimate the happiness of the scene. Indeed, Ray does not provide an easy solution to the workaday bourgeois lifestyle, with its moral and economic hardships. After leaving her job, Arati tells Subrata that she has quit and why, and now their household has no income whatsoever. But Arati discovers that her husband considers her actions brave and, realizing her nobility, accepts her place by his side. Together, hand-in-hand, they head into the distance to search the city for work. The scene recalls the ending of Charles Chaplin’s Modern Times (1938), where the Little Tramp and Gamine face their future penniless, but together. The implications of this final moment in The Big City are not blind confidence that Arati and Subrata will inevitably find jobs and live happily ever after. Things are more uncertain. Ray implies that personal fulfillment comes with a risk—an awareness that whatever job they find, they may face another moral injustice inherent to patriarchal capitalist systems, and thus the struggle will continue. Ray does not celebrate the modern city as a progressive, cosmopolitan place where women can realize their highest potential; he sees the modern world as a place that has taken steps to improve from outdated traditions, and has the possibility of providing a better life, but still has much growing to do before it can supply unqualified happiness.

Unlike the Italian Neorealists or contemporary Third World filmmakers to which Ray is often compared, his films avoid typical realist formal techniques, such as handheld camerawork, unprofessional actors, and a harsh editing schema. The formal elements of a Satyajit Ray film, instead, are narrative cohesion and intentionally recessive formal techniques, bound by a profound humanist empathy. Ray believed in a Western brand of narrative linearity and avoided disorienting art for art’s sake in his formal approach. The cohesiveness between narrative and form remained essential to him, unlike many popular Indian films. He believed that the artists making a film should not be noticed: the writer should not be noticed as the viewer listens to the dialogue; the cinematographer should not move the camera in a way that distracts from the story; the designers should not ornament beyond what is needed for the camera; the editor should not call attention to their cuts. This has made it challenging for many critics and scholars to pinpoint Ray’s style, which often results in his East-meets-West associations or false claims that he occupies what he himself described as a “truly indigenous” style—an almost impossible notion with cultural exchanges and influences occurring in cinema at all times.

Reading any assessment of Ray’s style, words like “authentic” and “naturalistic” and “realistic” come to the fore; however, Ray does more than merely shoot reality. He labors over his aesthetic with a perfectionist’s eye to achieve a specific result. Ray once said, for a director “there is no ready-made reality which he can straightaway capture on film. What surrounds him is only raw material. Objects, locales, people, speech, viewpoints—everything must be carefully chosen, to serve the ends of his story. In other words, creating reality is part of the creative process.” Ray acknowledged that, for instance, Italian Neorealists created the impression of reality through their artistry and, furthermore, Neorealists achieved their apparent reality and grittiness through significant aesthetic choices and affectations. As he wrote later in life, Ray sought a sort of realism to “strike a mean between naturalism and a certain thing which is artistic, which is selective.” In this purposeful approach, every device in the filmmaker’s toolkit must serve the story, resulting in films that remain unobtrusive, never flashy, whereas small artistic flourishes remain restricted to a sly camera angle, his blocking, or his subtle use of light. He believed all of the filmmaking craftspeople should serve the material to achieve a cohesive whole. Proof of the deliberateness of his style appears in his theoretical writings on cinema and his anthology of film criticism in Our Films Their Films (1976) and On Cinema (1982), in which he discusses the aesthetics of even the most realistic film subjects as a labored-over application of form.

Watching The Big City, one notices his concentration on intimate details that avoid exposition, unlike the typical Indian film from Mumbai. For instance, Ray captures equal measures of labor and lack of ceremony around meals in the household; although much effort goes into arranging a meal and preparing it correctly, its consumption occurs with little consequence. Sequences such as these saturate the viewer in details, objects, and behavior that exists extraneously to the plot but adds to the audience’s ability to understand the culture of his characters. His aesthetic goal, then, resides in creating a mood and telling a story through a simplicity of images. He seeks to create meaning through a minimal use of form, avoiding the typical expectations associated with, say, Mumbai cinema or the Hollywood films that Ray so adored. More than his other pictures, The Big City resists grand camera movements or spectacle, adopting in their place a scaled-down use of image, contrary to the expressivity, aggressive editing, jump-cuts, and stylistic gestures used by Italian Neorealists and more political Third World filmmakers to contrive realism. Ray’s restraint provides full immersion into his world and a lucidity of character and theme.

Watching The Big City, one notices his concentration on intimate details that avoid exposition, unlike the typical Indian film from Mumbai. For instance, Ray captures equal measures of labor and lack of ceremony around meals in the household; although much effort goes into arranging a meal and preparing it correctly, its consumption occurs with little consequence. Sequences such as these saturate the viewer in details, objects, and behavior that exists extraneously to the plot but adds to the audience’s ability to understand the culture of his characters. His aesthetic goal, then, resides in creating a mood and telling a story through a simplicity of images. He seeks to create meaning through a minimal use of form, avoiding the typical expectations associated with, say, Mumbai cinema or the Hollywood films that Ray so adored. More than his other pictures, The Big City resists grand camera movements or spectacle, adopting in their place a scaled-down use of image, contrary to the expressivity, aggressive editing, jump-cuts, and stylistic gestures used by Italian Neorealists and more political Third World filmmakers to contrive realism. Ray’s restraint provides full immersion into his world and a lucidity of character and theme.

As for the types of stories he told, Ray admitted he was more interested in narrative density than form. He concentrated on the inner lives of his characters, their thoughts and feelings. Following the teachings of Tagore, he explored the emotional, ideological, and internal worlds of his characters. Perhaps because of this, he often told stories about women in films, including The Big City, Charulata, and The Home and the World, revealing their concerns in a patriarchal society quick to overlook them. But his social commentaries, ranging from postcolonial identity to the roles of women in Indian society, never emerge as a message or obtrusive theme; they are the underpinning elements in the daily lives of Ray’s characters—the real subject of his films. This is not to suggest his films lack a dramatic shift, as his characters frequently moved from one state to another, such as Arati’s growth from a contained housewife to a valued worker to a woman finding her place in the modern world. But his characters’ shifting states are not violent or rarely action-oriented; he avoided depicting violence and sex, and he resisted telling a grand epic story or concentrating on a journey. The Big City is less concerned about exploring the modern metropolis in sprawling detail than the relationship between Arati and Subrata, and what the modern city puts them through.

These concerns emerge in The Big City as a portrait of an ongoing debate, as opposed to a resolution within that debate, about the gender politics, family dynamics, and cultural interactions that occur in the contemporary world. Ray’s concentration on the inwardness of his characters, their conscience in the face of injustice, as well as their moral and emotional questions, leads to a beautiful and unfortunately timeless film that, regardless of its cultural specificity to a noted time and place in Indian history, has social relevance today around the world. Regardless of the regularity with which women hold important positions in all manner of professions, women still struggle for equal footing. In essence, patriarchal and capitalistic systems have not changed since the film’s release in 1963, in that women face many of the same issues, and moral questions still arise in occupational spaces. The enduring quality of The Big City, beyond its heartening characters, charmed performances, or elegant simplicity of Ray’s direction, is that it recognizes the forward steps taken toward personal and societal fulfillment, even while Ray’s worldview acknowledges their unattainability in the modern age.

Bibliography:

Dissanayake, Wimal. “Rethinking Indian Popular Cinema Towards Newer Frames of Understanding” Rethinking Third Cinema. Gunerante, Anthony R., and Wimal Dissanayake, editors. Routledge, 2003.

Ganguly, Keya. Cinema, Emergence, and the Films of Satyajit Ray. University of California Press, 2010.

Robinson, Andrew. Satyajit Ray: The Inner Eye. Second Edition, I.B. Tauris, 2004.

Roy, Binayak. “Ray: The Last Phase.” Film International, vol. 10, no. 2, June 2012, pp. 42-52.

Sengoopta, Chandak. “‘The Fruits of Independence’: Satyajit Ray, Indian Nationhood and the Spectre of Empire.” South Asian History and Culture, vol. 2, no. 3, 01 July 2011, p. 374-396.

—. “‘The Universal Film for All of Us, Everywhere in the World’: Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali (1955) and the Shadow of Robert Flaherty.” Historical Journal of Film, Radio & Television, vol. 29, no. 3, Sept. 2009, pp. 277-293.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review