The Definitives

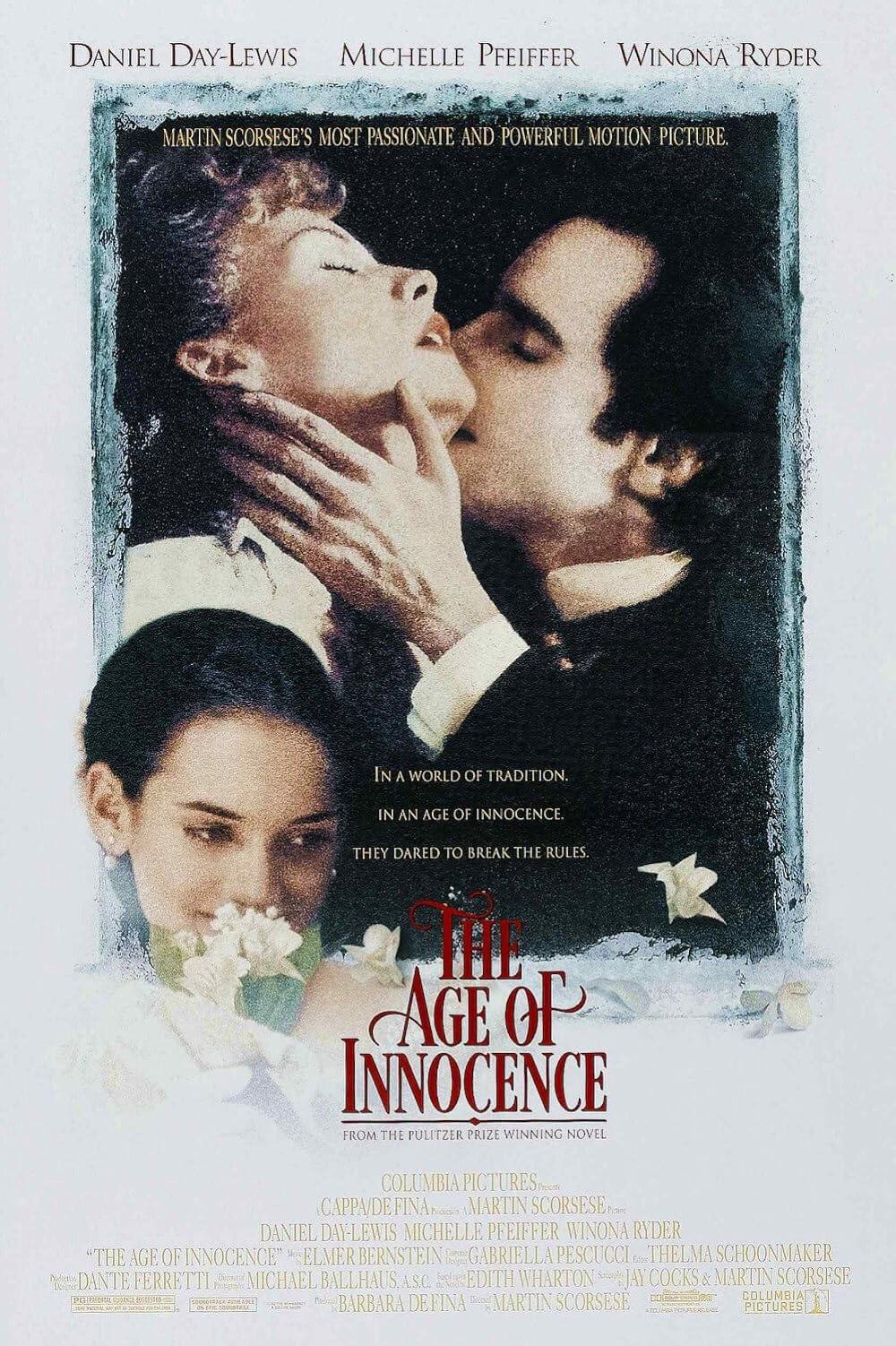

The Age of Innocence (1993)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

The Age of Innocence, a superb costume drama from director Martin Scorsese, takes place in New York City in the later part of the nineteenth century during the Gilded Age, a period in United States history where social problems were disguised by a false pretense and surface sheen. Scorsese’s career is filled with New York stories; however, they rarely take place in such fine surroundings. Films such as Mean Streets (1973), Taxi Driver (1976), After Hours (1985), Goodfellas (1990), and Bringing Out the Dead (1999) each reveals the seediness, psychological disturbance, and violence teeming within a filthy and obscene metropolis, where the city itself reflects the damaged characters. Here, Scorsese adapts Edith Wharton’s 1920 novel and explores how The Age of Innocence, on the exterior, has been steeped in a pretense of formal behavior, repressed romantic desires, conspicuous ornamentation, material goods, and above all the importance of outward appearances. But the social rules and heavily regulated manners of New York aristocrats, as opposed to the viciousness of the city, represent a brutality in this film more visceral than any of Scorsese’s more physically violent pictures—the type of film for which Scorsese is best known. The violence exists in the semiotics of worldly goods, via what the film’s omniscient narrator dubs “arbitrary signs” within the regimented social milieu, and a subtle set of unwritten rules enforced by expressly practiced class conventions, harshly dictating the lives of the late nineteenth century’s New York elite.

Edith Wharton’s novel was published in 1920, and the next year she became the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for literature. Booth Tarkington’s similarly themed novel The Magnificent Ambersons, which won the Pulitzer in 1919, parallels Wharton’s in that both became telling films of aristocratic life (The Magnificent Ambersons was, of course, adapted to film in 1941 by Orson Welles). What an enlightening experience it must have been to live in this setting; at least, that is what we think at first, until we realize the grueling niche requirements of this society. There are beauty and grace in this lifestyle as an objective observer, but most novels, histories, and sociological studies written about the period after-the-fact dwell on its downfalls. Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner’s The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today, published nearly 50 years before Wharton’s text, observed the materialism and greed of the time. But where Twain and Warner’s title is obvious, Wharton’s must be meant ironically: no one in this film is innocent. The characters are placed in an environment of repression, submission, and most of all, a stifling behavioral decorum that limits what a person can say, do, or even feel. Marriage is a contract, more about a vital link between two important families than two lovers. Love is irrational and impractical in this world. There is no personal life outside of what affects the family. If an act of social indiscretion transpires, all sects of the respective family become involved. After all, family names survive, the individuals therein do not.

Scorsese modeled his production after costume dramas of classic Hollywood, also known as women’s films or period pieces. Commonly “A” productions, such classic melodramas and romances featured women suffering from affairs of the heart, societal pressures, family dynamics, or an overarching historical event. Most were set in high society, sometimes Victorian England or an earlier period that allowed extravagant costumes and set pieces—anyplace that transported the mostly female viewers of the era, and their husbands and children, away from the drudgery of their daily lives, from the Depression to World War II. They featured stars like Greta Garbo, Bette Davis, and Olivia de Havilland, and they drew from sources in popular and prestige literature. Titles like Tarnished Lady (1931); Gone with the Wind, Marie Antoinette, and Jezebel in 1938; The Little Foxes (1941); and Jane Eyre (1943) inspired Scorsese’s treatment of The Age of Innocence. Above all of them, the director looked to Luchino Visconti’s sweeping historical epics, Senso (1954) and The Leopard (1963)—films of violent political change and melancholy.

Scorsese modeled his production after costume dramas of classic Hollywood, also known as women’s films or period pieces. Commonly “A” productions, such classic melodramas and romances featured women suffering from affairs of the heart, societal pressures, family dynamics, or an overarching historical event. Most were set in high society, sometimes Victorian England or an earlier period that allowed extravagant costumes and set pieces—anyplace that transported the mostly female viewers of the era, and their husbands and children, away from the drudgery of their daily lives, from the Depression to World War II. They featured stars like Greta Garbo, Bette Davis, and Olivia de Havilland, and they drew from sources in popular and prestige literature. Titles like Tarnished Lady (1931); Gone with the Wind, Marie Antoinette, and Jezebel in 1938; The Little Foxes (1941); and Jane Eyre (1943) inspired Scorsese’s treatment of The Age of Innocence. Above all of them, the director looked to Luchino Visconti’s sweeping historical epics, Senso (1954) and The Leopard (1963)—films of violent political change and melancholy.

Scorsese, who had grown up fascinated by every genre in the Golden Age of Hollywood, including costume dramas, had long sought to make a film of historical grandeur and unspoken emotions. His father Luciano, who was fascinated by historical costumes and to whom the film was dedicated, inspired the production. Alas, Luciano died before the film’s completion. Scorsese also pursued The Age of Innocence as his first period film because it allowed him to explore the history of his beloved New York, specifically the mid-nineteenth century’s upper class (he delved into the era’s lower classes in 2002’s Gangs of New York). Working from a screenplay he wrote alongside Jay Cocks, Scorsese’s production shot mostly in the Kaufman Astoria Studios in Queens, where the period’s tracery, embellishment, and extravagance could be recreated through lavish mise-en-scène. Director of photography Michael Ballhaus shoots with an ever-roving camera to satiate the viewer in sensory input, borrowing from the Max Ophüls style of complex and fluid images, while production designer Gabriella Pescucci researched details for gorgeous sets, costumes, and decorations—another Ophüls touch.

To capture the world of Wharton’s novel, Cocks and Scorsese’s script kept the voice of the author’s prose intact through the all-seeing narrator, voiced by Joanne Woodward. Her matter-of-fact observations and the tone of her voice capture what Scorsese called “the chill bemused irony of the narration” in Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon (1975), an inspiration to the director in more than just the narration. Woodward’s voice describes and critiques the world portrayed in the film: “This was a world balanced so precariously that its harmony could be shattered by a whisper.” What was essential to the narration for Scorsese was its ability to turn “the drama gradually from shrewd observation of 19th Century English mores into a complex poignant portrait of vanity and ambition.” The narrator remarks, “It was widely known in New York, but never acknowledged, that Americans want to get away from amusement even more quickly than they want to get to it.” Scorsese also created parallels between the dramatic themes in the narrative and the background decorations, paintings, and décor in his film—a similar approach to Kubrick, who placed his small characters within a vast frame, much like the landscapes on display throughout his film.

To capture the world of Wharton’s novel, Cocks and Scorsese’s script kept the voice of the author’s prose intact through the all-seeing narrator, voiced by Joanne Woodward. Her matter-of-fact observations and the tone of her voice capture what Scorsese called “the chill bemused irony of the narration” in Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon (1975), an inspiration to the director in more than just the narration. Woodward’s voice describes and critiques the world portrayed in the film: “This was a world balanced so precariously that its harmony could be shattered by a whisper.” What was essential to the narration for Scorsese was its ability to turn “the drama gradually from shrewd observation of 19th Century English mores into a complex poignant portrait of vanity and ambition.” The narrator remarks, “It was widely known in New York, but never acknowledged, that Americans want to get away from amusement even more quickly than they want to get to it.” Scorsese also created parallels between the dramatic themes in the narrative and the background decorations, paintings, and décor in his film—a similar approach to Kubrick, who placed his small characters within a vast frame, much like the landscapes on display throughout his film.

Set inside some of the late nineteenth century’s richest New York homes, the emotional violence that drives the film thematically is hidden behind an intricate, decorative splendor. Scorsese’s camera cleverly spends more time on objects than on his characters’ faces. When someone enters a room, we are given only a glimpse of the individual; instead, Ballhaus’ camera moves around the room from behind them, allowing the audience to absorb the ornamentation from the character’s perspective. Much of the film and Woodward’s narration concentrates on art, flowers, exorbitant food, dress, imported furniture, and all the trappings of material wealth—those “arbitrary signs” that must be read and deciphered by the social class that depends on them. The material environment is perhaps its most relevant character, not one detail insignificant but all of it superfluous. So much material wealth is on display in the film that, though at first it appears as a feast for the eyes, the viewer becomes almost sickened by it later after we realize the emptiness of its purpose. Much like the film’s characters, we conform to the surroundings as the film goes on, taking it for granted. But ultimately, we want to break out of that world, just as the film’s protagonist does, because he is eventually forced into accepting conformity—his fate dictated by behavioral decorum. The editing is just as sumptuous. Thelma Schoonmaker overlays one image with the next, ever-dissolving in an orgiastic flow of visual stimulation, transitioning between paintings, cutlery, and mouth-wateringly decadent cuisine—all of which the film’s characters seem uninterested in and complacent about. Schoonmaker also dissolves into visual blushes, a solid color (red, yellow) that represents an internalized emotion experienced by a character. Scorsese’s entire visual approach is both historically accurate and a perfect metaphor for this world.

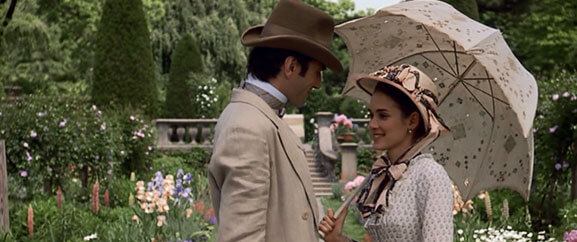

Daniel Day-Lewis plays young attorney Newland Archer, outwardly engaged to the young May Welland (Winona Ryder) for love. We gather that love was only the offshoot, perhaps the illusion forced by an arranged coupling. Newland’s true passion is for the Countess Olenska (Michelle Pfeiffer), a social outcast from Poland and May’s cousin. Countess Olenska has returned to New York after a scandalous decision to leave her husband, personifying rebellion in her willingness to assert her own desires, thus all the more attractive to the reticent Archer. Rumors of divorce and free romantic associations surround the Countess, and so she finds herself ostracized by the New York elite. Even before this scandal, Wharton writes she was “the cousin always referred to in the family as ‘poor Ellen Olenska,’” though she’s hardly pathetic or pitiable. Dressing faintly different from everyone else, the Countess is perhaps not as fashionable and perhaps simply too foreign for aristocratic New Yorkers of the period. Either way, her offbeat wardrobe serves to exemplify her status as an outsider. Olenska’s behavior excludes her even more, while the social scathing of the era seems to have no effect on her. Like Wharton’s novel, Scorsese portrays Olenska’s rebellion delicately; the audience, as a result, finds Olenska admirable, if not dignified, compared to the shallow world of nineteenth-century New York.

Daniel Day-Lewis plays young attorney Newland Archer, outwardly engaged to the young May Welland (Winona Ryder) for love. We gather that love was only the offshoot, perhaps the illusion forced by an arranged coupling. Newland’s true passion is for the Countess Olenska (Michelle Pfeiffer), a social outcast from Poland and May’s cousin. Countess Olenska has returned to New York after a scandalous decision to leave her husband, personifying rebellion in her willingness to assert her own desires, thus all the more attractive to the reticent Archer. Rumors of divorce and free romantic associations surround the Countess, and so she finds herself ostracized by the New York elite. Even before this scandal, Wharton writes she was “the cousin always referred to in the family as ‘poor Ellen Olenska,’” though she’s hardly pathetic or pitiable. Dressing faintly different from everyone else, the Countess is perhaps not as fashionable and perhaps simply too foreign for aristocratic New Yorkers of the period. Either way, her offbeat wardrobe serves to exemplify her status as an outsider. Olenska’s behavior excludes her even more, while the social scathing of the era seems to have no effect on her. Like Wharton’s novel, Scorsese portrays Olenska’s rebellion delicately; the audience, as a result, finds Olenska admirable, if not dignified, compared to the shallow world of nineteenth-century New York.

Olenska is another in a long line of Scorsese’s outsiders who circles a precise, ultimately oppressive social culture while remaining unable to gain acceptance. Although her family was originally part of the New York elite when she was very young, they’re described as a nomadic clan; the Olenskas traveled the world, and upon returning considered themselves among friends, which is untrue. The Countess becomes the subject of cruel gossip by many and remains in a state of social ostracization. This is the fate of several Scorsese characters. Consider Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver, a character that will never fit in with the attractive political campaigners, Cybill Shepherd and Albert Brooks. In After Hours, Griffin Dunne voyages into the oddball world of Manhattan’s SoHo neighborhood and finds himself chased out of it. Rigid social systems also inform Scorsese’s gangster films. The “Irish blood” of Ray Liotta’s character in Goodfellas prevents him from being fully made in the Italian mafia, while the mobsters in Casino (1995) are never quite accepted into the Las Vegas inner circle. By contrast, The King of Comedy (1982), one of Scorsese’s only comic films, features Robert De Niro as the hapless and pathetic Rupert Pupkin who hopes to break into show business; and while he’s eventually accepted, he must resort to kidnapping to penetrate the social group of elitist entertainers. Scorsese’s theme of outsiders is never more oppressive or formative for the story than in The Age of Innocence.

Despite Olenska’s status as an outsider, Newland admires her nonconformities and agrees with her unpopular views; but he simply does not speak of his beliefs in public. He barely thinks of them, driven by his overwhelming desire to remain a part of his society and adhere to its crucial etiquette. Newland is an outsider too, except only in his own mind, where he often wanders off, lost in thought. At one point we see Newland looking into a museum window at an ancient tool with a placard reading, “Use Unknown.” Newland identifies with it. But then there’s the young May, representing the antithesis of nonconformity. She is the epitome of proper. Given his engagement to her, Newland struggles to weigh the importance of social codes versus his personal yearnings. In the end, he ultimately abandons his desire and the Countess for May because it is the “correct” and “appropriate” thing to do. This decision destroys his chances of achieving his heart’s definition of happiness and love with Olenska, but he assimilates to his society’s definitions thereof and does what’s expected of him. He must endure being with May, just as Olenska must endure living under constant inspection. Their world is too rooted in observation and judgment to exist outside of it—to try would represent an attack on the social structure of the time, and would, therefore, result in a cruel banishment. More than any other social group in Scorsese’s oeuvre, the upper-class New Yorkers in The Age of Innocence demand conformity in mind, body, behavior, and spirit.

Despite Olenska’s status as an outsider, Newland admires her nonconformities and agrees with her unpopular views; but he simply does not speak of his beliefs in public. He barely thinks of them, driven by his overwhelming desire to remain a part of his society and adhere to its crucial etiquette. Newland is an outsider too, except only in his own mind, where he often wanders off, lost in thought. At one point we see Newland looking into a museum window at an ancient tool with a placard reading, “Use Unknown.” Newland identifies with it. But then there’s the young May, representing the antithesis of nonconformity. She is the epitome of proper. Given his engagement to her, Newland struggles to weigh the importance of social codes versus his personal yearnings. In the end, he ultimately abandons his desire and the Countess for May because it is the “correct” and “appropriate” thing to do. This decision destroys his chances of achieving his heart’s definition of happiness and love with Olenska, but he assimilates to his society’s definitions thereof and does what’s expected of him. He must endure being with May, just as Olenska must endure living under constant inspection. Their world is too rooted in observation and judgment to exist outside of it—to try would represent an attack on the social structure of the time, and would, therefore, result in a cruel banishment. More than any other social group in Scorsese’s oeuvre, the upper-class New Yorkers in The Age of Innocence demand conformity in mind, body, behavior, and spirit.

Motion pictures have staged several examples from which audiences might learn these same, harsh lessons about accepting one’s unfortunate social lot: the most comparable to Scorsese’s film is William Wyler’s 1949 adaptation of The Heiress. Both The Age of Innocence’s May Welland and The Heiress’ Catherine Sloper are pressed under the same thumb. Played by Ryder and Olivia DeHavilland respectively, both actresses portray a meek vulnerability, as if at any moment their world is going to swallow them up. Both May and Catherine, whether they are a willing participant or a victim in their world, are subject to emotional suffering as a result of social demands. Before she can be whole, Catherine, at once innocent and ignorant of how people view her (specifically her father), must come to the realization that her father despises her, and that her supposed lover is a gold-digger. Being an outcast, she lashes out. Conversely, May is spared that trauma; Archer’s respect for social rules forces him to keep silent and complacent in their loveless marriage. May avoids being confronted by the world she has never had the opportunity to explore. Scrutinized and subjected to the community’s watchful eye, the film’s characters carefully maintain their manners. The scandalous nature of the film is restrained—the audience must consider the setting, the characters, and their behavior carefully to fully grasp the violence therein.

There are no explicit sexual affairs in The Age of Innocence; the film’s most “indecent” moment is a passionate scene in a carriage where Newland removes his glove and delicately undoes the buttons on the Countess Olenska’s glove. He touches his bare hand to hers and gently kisses her wrist, while the world outside the carriage seems to loom over their actions. Once the viewer accepts the film’s surroundings, a period when conformity is the only rule, the viewer realizes that regardless of the film’s PG rating, a simple scene depicting the kissing of a wrist in this public setting is nearly pornographic. There are also no moments of bloody violence. There are only moments of severe social punishment and psychological torment that ultimately prove more relatable, and more painful, for the viewer than any physical attacks in Scorsese’s work. Considering this: The Age of Innocence stands as the more emotionally violent of Scorsese’s two pictures set in late nineteenth century New York (the other being Gangs of New York). The world Scorsese creates here provides scenes of horrible emotional regret and betrayal, more potent than any of the bloody images of Goodfellas or Casino. The romantic impact is much more tangible than the literal violence with which the director is traditionally associated.

There are no explicit sexual affairs in The Age of Innocence; the film’s most “indecent” moment is a passionate scene in a carriage where Newland removes his glove and delicately undoes the buttons on the Countess Olenska’s glove. He touches his bare hand to hers and gently kisses her wrist, while the world outside the carriage seems to loom over their actions. Once the viewer accepts the film’s surroundings, a period when conformity is the only rule, the viewer realizes that regardless of the film’s PG rating, a simple scene depicting the kissing of a wrist in this public setting is nearly pornographic. There are also no moments of bloody violence. There are only moments of severe social punishment and psychological torment that ultimately prove more relatable, and more painful, for the viewer than any physical attacks in Scorsese’s work. Considering this: The Age of Innocence stands as the more emotionally violent of Scorsese’s two pictures set in late nineteenth century New York (the other being Gangs of New York). The world Scorsese creates here provides scenes of horrible emotional regret and betrayal, more potent than any of the bloody images of Goodfellas or Casino. The romantic impact is much more tangible than the literal violence with which the director is traditionally associated.

Scorsese makes a vital comparison between the film’s emotional violence and its physical equivalent. When touring the home of socialite Mrs. Mingott (Miriam Margolyes), the camera spotlights a historical parallel: a painting that depicts two Native Americans as they restrain a young white woman and prepare to scalp her. Within the ranks of Wharton’s New York aristocracy, a similar kind of attack occurs when someone like Olenska penetrates their territory; to keep marriages like Archer and May’s whole, the Olenskas are deemed outsiders and must be dealt with. Scorsese dwells on the image to signify the aristocratic circle’s persecution of the individual by way of conformity—a metaphor for the picture’s emotional violence. The film proves disturbing, as every time Newland or Olenska gather the slightest reprieve from their social imprisonment, Scorsese allows his audience to sigh, to escape as his characters do, only to be aggressively thrust back into the reality of the social convention. We are Scorsese’s puppets, wisped around in emotional circles, just as Newland, Olenska, May, and the rest of late nineteenth century New York were in their time. While The Age of Innocence does not appear to flow within the director’s primary thematic stream, it offers depictions of brutality, cruelty, and violence as relentless as his most popular work. Although Goodfellas has often been cited as Scorsese’s finest film, take away the physical violence, guns, and foul language and what do you have? A drama about conformity. The importance of conforming to the mafia’s set way of life is just as significant as conforming to late nineteenth century edicts of behavior, and for dissidents, the punishments are just as severe.

(Editor’s Note: The above article was expanded from the original version, first published on February 20, 2007.)

Bibliography:

Christie, Ian; Thompson, David (edited by). Scorsese on Scorsese. Revised Edition. London: Faber, 2003.

LoBrutto, Vincent. Martin Scorsese: A Biography. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc., 2008.

Knight, Deborah. “The Age of Innocence: Social Semiotics, Desire, and Constraint.” The Philosophy of Martin Scorsese. Ed. Mark Conrad. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2007.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review