The Definitives

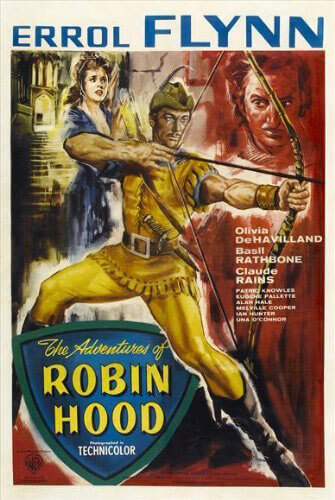

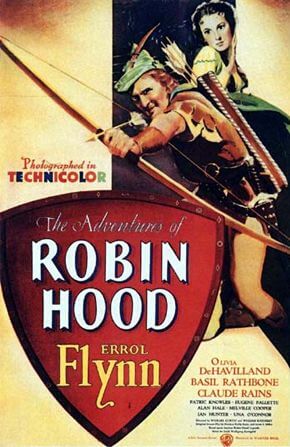

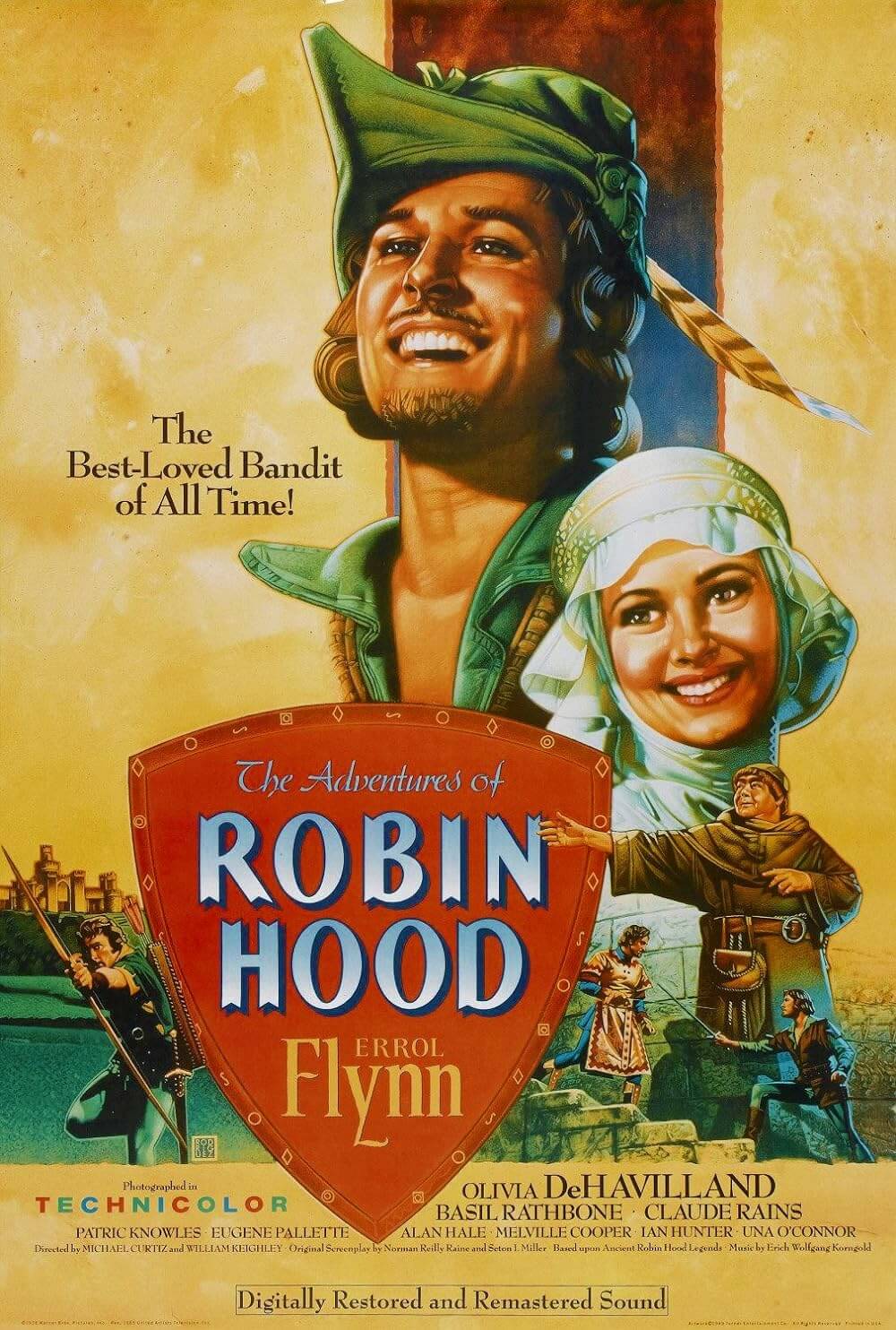

The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

For The Adventures of Robin Hood, Warner Bros. assembled its finest talent both on and offscreen to create their first grand Technicolor production in 1939. In turn, it produced one of the most iconic motion pictures ever put to celluloid. A swashbuckling costume epic blooming with primary colors, painted with an idyllic sense of romance and adventure, the film provides audiences with an experience as compelling and joyful as escapist entertainment can provide. It demands hyperbole with words like “perfect” and “masterpiece,” words often used to describe films without considering their meaning. But The Adventures of Robin Hood exemplifies those terms completely, even advances their implications in its universal appeal. This is a picture for everyone. Warner Bros. adapts the Robin Hood legend, an English tale known throughout the world, with full surrender to the dreamy narratives of children’s books, but in such a way that it appeals best to adults embracing their inner child. It’s an effortless and unaging delight, and its journey to the screen is the stuff of legend within the Golden Age of Hollywood. The studio’s production proved expensive and punishing for the filmmakers, led to career-making performances, and even saved lives. The ensuing history and appreciation details the film’s production while also providing commentary and background on the talent involved, notably Errol Flynn, who headlined a cast of classic Hollywood’s finest talent in this effortless, delightful, marvel of a film.

In the mid-1930s, each of the Big Five studios had their genre, and Warner Bros. was known for James Cagney’s gangster pictures and Busby Berkeley musicals. For years, films like The Public Enemy (1931) and The Gold Diggers of 1935 sustained the studio’s financial position, while the limited diversity of their output hindered the studio’s reputation. A surprising development occurred when Warner Bros. gathered a hefty profit from two costume pictures released in 1935, A Midsummer Night’s Dream and William Keighley’s version of The Prince and the Pauper. With the possibility of a new genre earning money for the studio, namely the prestige picture, Warner decided to revisit England’s most beloved bandit, Robin Hood—a legend of uncommon repute among audiences. When Warner moved to adapt the operetta Robin Hood, written by Reginald de Koven and Harry B. Smith, they found MGM had the same idea, only the competition planned to make a musical. Warner wanted an adventure picture, and so the two studios resolved that Warner would be given the operetta’s story rights while MGM received the rights to the music and the title “Robin Hood.” This meant Warner needed another name for their picture. Hence, The Adventures of Robin Hood was born. Incidentally, MGM never made their musical.

Adapted for the screen three times in previous years, Robin Hood’s story was already made into an iconic feature: the silent version by Douglas Fairbanks, entitled Douglas Fairbanks in Robin Hood (1922). Fairbanks’ production floated over Warner Bros. like a miasma, threatening the success of their new venture by reputation alone. Fairbanks himself represented a menace to Warner Bros.; the beloved swashbuckler was held in high regard by audiences, and his trademark showmanship was yet unmatched by other screen talents. The studio cautiously proceeded by assuring that every aspect of their production would be bigger and better than Fairbanks’ version. Producer Hal B. Wallis asserted that their A-list project should maintain the same ferocity as Fairbanks’ film but improve upon it by optimizing the studio’s top resources, among them the newfangled color photography process. Meanwhile, writers Norman Reilly Raine and Seton I. Miller began researching the Robin Hood fable to structure a story so grandiose and so universal that adults and children alike would forget Fairbanks’ picture and be swept away by the extravagance of the new version. Children desired storybook action, but the narrative could not exclusively cater to youngsters, or adults would be bored. What would interest adults beyond the spectacle of the production? Telling an exciting story with a dash of romance and modern-day relevance might do the trick.

The screen story was derived from Sir Walter Scott’s novel Ivanhoe, several of the original medieval ballads about Robin Hood, and Howard Pyle’s writings from the latter part of the nineteenth century. Pyle’s 1883 novel The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood of Great Renown, in Nottinghamshire profoundly influenced screenwriters Raine and Miller. Pyle’s Arcadian storytelling described an idyllic world bereft of foul weather “where flowers bloom forever and birds are always singing.” Pyle’s text gives a lighthearted approach to the material, embracing a mythological yet childlike innocence. Everything real or historical is cleaned away and replaced by elements of fantastical, impassioned entertainment. Heavily romanticized illustrations by Pyle and an idealistic sense of representation gave art director Carl Jules Weyl (who would later put his skills to use on Casablanca, The Big Sleep, and Yankee Doodle Dandy) and costume designer Milo Anderson (Gentleman Jim and The Prince and Pauper) the material from which The Adventures of Robin Hood would gather its acclaimed storybook presentation.

After compiling, reviewing, and dissecting numerous sources, Raine and Miller constructed what is now considered the model Robin Hood scenario: King Richard the Lionheart is held captive while on the Crusades. His kingdom is left to Prince John, who tells the Saxons that he’s increasing taxes to raise the ransom for their king. John uses the taxes to increase Norman power and take over the throne. Robin of Locksley sees through Prince John’s plot and seeks to expose and defeat the corruption and power-hungry aspirations of the throne’s enemies. Robin and Will Scarlett recruit Little John, Friar Tuck, and a band of Merry Men to restore order and freedom to England. They steal from the rich and give to the poor, helping alleviate the unjust taxation ordered by Prince John. Maid Marian, a Norman, begins on John’s side; however, she soon sees Saxon living conditions and sympathizes with their positions, falling in love with Robin in the process. John’s forces, led by Sir Guy of Gisbourne and the Sheriff of Nottingham, do everything they can to stop the hero, but through dauntless battle after battle, they find themselves beaten. By the end of the tale, Robin Hood wins Maid Marian’s heart, proves he is the finest archer in all of England, kills the bad Guy, and turns over the restored kingdom to King Richard.

Since the middle ages, various print and film versions of the Robin Hood legend make inconsistent use of characters such as the Sheriff of Nottingham, Sir Guy of Gisbourne, or, strangely, even Maid Marian. Walt Disney’s animated 1973 cartoon Robin Hood has no mention of Sir Guy, nor does Disney’s live-action 1952 version. Kevin Reynolds’ Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991) forgot all about Prince John and, in the extended version, claims that the Sheriff of Nottingham engaged in witchcraft. The earliest Robin Hood ballads from the fourteenth century did not include Marian, which leads historians to believe she never actually existed—that writers first wrote about her when romantics later demanded that Robin have a bride. Maid Marian, for Robin Hood, builds morals and morale; she humanizes him and makes him a complete man, in the sense that every complete man of traditional folktales has a woman to love. In many legends, Marian is considered a virginal maid; this association links her with Christianity’s virginal maid, the Virgin Mary. Some scholars have written that Marian derives from a character created for May Day—a festival widely celebrated in England that included Robin Hood as a pivotal character in its games. Wherever Marian’s origins reside, her incarnation strengthens the hero through the embodiment of love from medieval storytelling.

From Piers Plowman’s first mention of Robin in his Middle English narratives to more recent incarnations, Robin Hood remains a figure of stability and defiance in the face of corruption. A hero that does not change, he forever stands for impartiality and fairness. He comforts audiences by reviving their faith in the goodness of the human spirit. For hundreds of years, Robin Hood’s legend gained support from the people, speaking to common folk more than any other class. Perhaps the appeal is that Robin begins as a rebel or bandit in the eyes of a crooked kingdom, and then later, his tale follows a David and Goliath structure that appeals to the underclasses. A freedom fighter for the masses, Robin Hood’s legend tells every man, woman, and child to keep a watchful eye on their kingdom or government and then provides inspiration, if not instruction, for what must be done about corrupt governments. It’s no coincidence that Warner Bros. was the most outspoken anti-Nazi studio in the late 1930s; to be sure, the film can be read as an allegory for rebelling against dictatorial regimes. Furthermore, the story wraps its commentary on political and ethical morality into an adventure, wherein the archer and sword-fighting hero fearlessly engages the deceitful government through a humiliating ruse, thievery, and eventually violence—all while bound by a righteous objective.

Casting the legendary bandit became Warner Bros.’ first problem. James Cagney, the star of Warner’s hits The Public Enemy and ‘G’ Men (1935), was the studio’s initial choice to play Robin Hood. A song and dance man, Cagney became typecast into tough-guy gangster pictures and found success in that genre while under contract with the studio. Though Cagney was incomparable in many roles like White Heat (1949), his physical appearance and onscreen reputation lacked the appropriate carriage to accomplish a triumphant Robin Hood performance. (Think of it: a short, scowling Robin Hood with a sour expression, snapping “You dirty rat” to Sir Guy.) Luckily, the actor backed out of his contract due to his ongoing disputes with the studio, and producer Hal B. Wallis was left to scout another lead for his production. At the time, Errol Flynn, another Warner contract actor but sorely underused, spent most of his workdays playing tennis and getting himself into trouble on the studio lots. Unlike some actors in the mid-thirties who were making upwards of ten movies a year, Flynn averaged one or two roles annually. His first hit came in 1935, with Captain Blood, and would imprint him onto a genre that would chase, if not haunt, the enigmatic actor for the rest of his life. Captain Blood is an uncommon pirate adventure filled with swashbuckling battles and a confident Flynn performance that actors still mimic to no avail today. Nevertheless, it was a box office smash and turned the unknown Flynn into an overnight star. The Charge of the Light Brigade and The Prince and the Pauper, released in 1936 and 1937 respectively, further encouraged Flynn’s dauntless ego and situated his lovable onscreen persona, peaking with The Adventures of Robin Hood. After approval from Jack Warner, Wallis chose the twenty-eight-year-old Flynn to star in Warner Bros.’s new costume epic, giving the actor a career-making opportunity.

The part demanded that Flynn play a character with traits similar to his own more respectable qualities: confidence, a lean physique, a handsome smile, and a surplus of charm. Though Flynn could tap into those swashbuckling talents employed on the set of Captain Blood, he approached the part with hesitation. He was adamant that audiences forget Fairbanks’ version of the character and focus on his own interpretation. Flynn’s Robin Hood relies on boyish charms and a believable physical performance, which mirror Flynn’s off-screen persona. Certainly, the exploits of a practical joker, lover, carouser, and trouble-maker Errol Flynn are now included among some of Hollywood’s best anecdotal lore. In a story that illustrates the actor’s love for a fight, director John Houston (The Maltese Falcon and The Treasure of Sierra Madre) often spoke of when Flynn called Houston’s friend a so-and-so at a Hollywood party. Houston confronted Flynn about the remark, and Flynn suggested they duke it out to resolve their dispute. Both men of impressive physical size pounded on each other for several minutes until, bloodied and tired, they agreed to stop and return to the party. Aside from scampering around Hollywood, Flynn’s reputation for adventure surpassed him. The actor was a well-known womanizer. His autobiography is filled with story after story of being chased out of bedroom windows by angry husbands. Flynn once said, “If I have any genius, it’s a genius for living.” The actor’s often disputed real-life adventures ranged from owning a tobacco plantation in New Guinea to diamond smuggling to nearly meeting his death in uncountable countries worldwide. One must wonder why Hollywood has not seen fit to produce “The Adventures of Errol Flynn” into a rousing feature—possibly because many of these stories have been questioned over the years. The actor was a well-known embellisher of truths and not unsusceptible to scandal. His talent for storytelling is proven within his literary works: In addition to his wonderfully entertaining autobiography My Wicked, Wicked Ways, Flynn also wrote two novels entitled Beam Ends (1937) and Showdown (1946). “I got more of a kick out of writing than I do out of making pictures,” Flynn once said.

With Robin Hood cast, Warner Bros. assigned the best of their contract players to other roles. Few films were ever so flawlessly cast. Claude Rains, an actor and acting teacher at the Royal Academy of Arts, was cast as Prince John. Rains could play anything and often did—from the title role in The Invisible Man (1933) to Captain Renault in Casablanca, howling the sharpest evil laugh or offering a mischievous half-smile. In Alfred Hitchcock’s 1946 film Notorious, Rains plays a Nazi living in secret in South America; the actor lends his role incredible charisma (only an actor of Rains’ capacity could make a Nazi sympathetic). Though a chameleon with his eyes and voice, that suave hair and those impressive good looks always remained whether he played madman or inamorato. He truly delivers Prince John’s dialogue, which another actor might have rendered hokey, relating the character’s schemes and tyranny with menace. Basil Rathbone, who played the villain in Captain Blood, would once again play Flynn’s antagonist as Sir Guy of Gisbourne, the villainous right hand of Prince John. Rathbone most commonly played two types of roles throughout his career: The clever male lead or the insidious villain. His famous portrayals of Sherlock Holmes were his most beloved, wherein Rathbone conveys the wry traits of the genius sleuth. Revisiting the part or the equivalent thereof in upwards of twenty films, he even voiced the title character in Disney’s 1986 animated feature The Great Mouse Detective.

On Robin’s side, character actor Alan Hale played Little John in the Douglas Fairbanks version and was cast in the role again for The Adventures of Robin Hood. Hale would reprise the part for a third time in 1950’s Rogues of Sherwood Forest, marking the first time an actor was recast in the same role three times in three unrelated productions. Hale worked with Flynn on several pictures: Dodge City (1939), The Sea Hawk (1940), and Gentleman Jim (1942). On each, he carries the nature of a lovable bear—sweet, but if necessary, aggressive. When Hale’s Little John and Flynn’s Robin Hood first meet, Robin finds himself knocked into a stream, laughing at the underestimated strength of his opponent. Hale’s presence onscreen, also underestimated, was comparatively bold. Maid Marian, intended to be a vision of both beauty and innocence, is given spotless clarity by Hollywood beauty Olivia de Havilland, who worked with Flynn on a total of eight pictures. The actress fell in love with Flynn during their many collaborations, but she stayed away because of his childishness and self-destructive nature. Even so, a true adoration existed between De Havilland and Flynn, but nothing ever came of their off-screen romantic feelings. Their mutual attraction for one another began on the set of Captain Blood, although she refused to let anything happen as he was married to actress Lili Damita (though that certainly would not have stopped Flynn). De Havilland claims that Flynn’s film career goals were based solely on money and success; she demanded more—she wanted artistic integrity. The combination of Flynn’s juvenile behavior and his superficial attitude towards acting may have, to a degree, prevented her from pursuing a love affair.

De Havilland insists, however, that the two did have a passionate life together: their onscreen romances. “He was a charming and magnetic man, but so tormented. I don’t know about what, but tormented,” she said of him. On the set of The Adventures of Robin Hood, Flynn confessed to her that his marriage was over and would end in divorce, but De Havilland refused to engage until the divorce became official. Unfortunately, he would remain married to Damita until 1941, by which time De Havilland had given up on Flynn’s destructive behavior. The onscreen romance between Robin and Marian, however, plays out just as it should. De Havilland’s Marian comes to us in bright colors, the way—after seeing this film and Gone with the Wind—she was supposed to be seen. Her facial nuances reveal absolute idealism and humanist devotion to the good, wholesome person that she is. In the scene where Marian visits the Saxon feast in Sherwood Forest, she walks through the masses, undeniably robed like the Blessèd Virgin, and becomes convinced by the power of Robin Hood’s just and honorable fight. An iconic embodiment of the role, there was no other actress in Hollywood, nor has there been one since, who could portray Marian so singularly.

Warner Bros. assigned several contract players to minor supporting roles. Melville Cooper (Four’s a Crowd and Rebecca) played a comedic and cowardly version of the Sheriff of Nottingham, leaving the true treachery to Rathbone’s Sir Guy and Rains’ Prince John. The toad-voiced Eugene Pallette (The Lady Eve and My Man Godfrey) gave Friar Tuck the wide, rustic, and jovial attributes often associated with the character. The memorable panic-stricken onlooker from The Invisible Man and Bride of Frankenstein (1932), Una O’Connor plays Marian’s attendant. David Niven, a longtime friend of Flynn, was the favorite for Will Scarlett, but Niven was in England when production began, so the role went to Patrick Knowles. Others include Ian Hunter as King Richard and even the famous Golden Palomino stallion Golden Cloud as Marian’s horse (Golden Cloud would later become Trigger, carrying Roy Rogers into the sunset on The Roy Rogers Show). With the cast in place, Hal B. Wallis and his crew began to deliberate over the film’s appearance. Howard Pyle’s work once again influenced the film’s structure, this time visually. Even though Pyle’s paintings were initially printed in black and white, the color spills off the pages from his volumes, flooding the reader with his rich prose. Warner and Wallis agreed that to captivate audiences, the full spectrum of the rainbow must appear on film, in unyielding beauty, without dullness or oppressive shadow. The only sufficient method of capturing Pyle’s romanticized visual style was Technicolor, specifically the three-strip process.

The potential beauty of three-strip processing was limitless, except the painstaking procedure could mean hell for the performers, camera operators, crew, and in particular, the film’s budget. It would take numerous technological improvements over more than a decade after The Adventures of Robin Hood’s release before the process became widely utilized. Pioneered in 1915 by Herbert Kalmus, Technicolor was for years considered impractical, even lacking artistic integrity compared to black and white film (in the same way that sound film was at first regarded as inferior to the artistry of a silent picture). The Gulf Between, made in 1918, was the first color film shot in the two-strip process (optimizing only red and green) and required a projector technician to maintain alignment of individual strips for each color, which made the process unfeasible for extensive use. After numerous failed innovations by Kalmus, Technicolor’s downfalls overcame its benefits, and the process was reserved primarily for short subjects and animated films. Even with the limited color palette Technicolor offered before 1932, producing full-length features proved too costly. As a result, Hollywood kept audiences in a monochromatic cinematic world. The fourth color process invented by Kalmus was three-strip Technicolor, where tones of red, green, and blue were separately recorded onto three individual strips of film. Walt Disney subjected his 1932 Silly Symphony cartoon Flowers and Trees to the procedure and gathered much praise for its use. Moving on to live-action, Technicolor helped produce La Cucaracha in 1934, a two-reel short costing roughly quadruple the amount of a traditional two-reel theme. The first full-length picture shot was Becky Sharp starring Miriam Hopkins, made by RKO Radio Pictures in 1935. It was a commercial and critical failure.

Technicolor, as a business, remained a separate entity from every movie studio. When a company like Warner Bros. shot using the procedure, Technicolor brought their technicians onto the set to manage the bulky cameras. Studios were required to rent Technicolor cameras; the equipment could not be purchased. And then later, they would develop and master the film outside the studio at Technicolor Inc. headquarters. Natalie Kalmus, Herbert’s wife, served as the liaison between Technicolor and the movie studios. She was part of the Technicolor deal, too, much to the dismay of many studios and their filmmakers. Reportedly, Mrs. Kalmus hampered productions, as she thought herself the legitimate art director on every Technicolor project on which she worked, offering insistent creative advice on the look of the film. Studios, specifically producer David O. Selznick, believed her presence on the set should have been limited to technical input. She was frequently shooed off the lot because of her poor reputation among Hollywood talent.

The Adventures of Robin Hood would become the second Technicolor feature at Warner Bros., the unsuccessful God’s Country and the Woman (1937) being the first. Because of the visual variety, outdoor shooting, intensity of the action scenes, and epic scale of the picture, which ironically stand as several reasons the movie remains iconic, the Technicolor photography drove the budget beyond Warner’s expectations. The studio began to sweat the costs, and with the procedural demands of the Technicolor process, the studio financiers were not alone in their sweating. Massive, blazing lights on the set (which brightened colors for photographic capture) also generated intense heat. Moreover, the performers, standing under the lights and sweating through their green tights or elaborate gowns, were forced to wait for unreasonable periods of time while Technicolor technicians formatted “The Lilly”—a color chart used to balance Technicolor cameras. More waiting was needed as the massive camera—a large, awkwardly shaped box—moved into position for the shot. The result of the afflictive planning, shooting, and processing of three-strip Technicolor sired many of the best movies ever made. The Adventures of Robin Hood exhibited only the first model for the procedure’s use and would be followed by masterpieces like Gone with the Wind and The Red Shoes (1948). The process transforms a film into pure splendor, affecting the viewer on emotional and physical levels. The color appears bolder, more complete onscreen, and therefore the punctuated light, received by the viewer’s eye, converts into an emotional reaction. The Adventures of Robin Hood, already a joyous film, instills a psychosomatic effect on the viewer. Audiences are helpless to what they’re shown; their stimulation is involuntary.

The film’s visually potent three-strip Technicolor outdoes the color of any motion picture made today. Still, because of the expense and inconvenience of the process, it is no longer used. Foxfire, completed in 1955 by Universal, was the last film to employ the technique. In the early 1950s, inventor George Eastman developed Eastman Color for Kodak, a single-strip negative process that captures the illusion of Technicolor on a single strip without the hulking camera and long, expensive processing time. Eastman Color meant prints could be produced and shipped faster to more theaters. Unfortunately, even though the Eastman process is now dubbed “Technicolor,” it fails to capture the same range as the three-strip process, which on one strip could capture extended versions of red, blue, or green. The main downfall of Eastman did not disclose itself until the 1980s, when early Eastman prints were found to have faded over time. Compared to three-strip Technicolor prints, which do not fade and still look as beautiful as the day they were processed, Eastman proves economically superior but lacks the durability required for quality film stock preservation. The resulting historical irony is that The Adventures of Robin Hood, shot in 1937, will forever look better than Jaws, filmed in 1974. Today, digital photography and transferring processes allow for limitless electronic vault capacity for film preservation. But even with the seemingly immeasurable possibilities of the digital camera and computer manipulation, the luscious glow of three-strip Technicolor cannot be matched.

The director of Warner’s first Technicolor feature God’s Country and the Woman, William Keighley, reigned over those bulky Technicolor cameras once again to helm The Adventures of Robin Hood. Keighley’s achievement on the period epic The Prince and the Pauper, starring Flynn, and his experience with three-strip processing made him the most practical choice for Warner. Having spent years on Broadway as an actor and director, Keighley became a Warner Bros. contract director in the early thirties. With him came aristocratic airs of superiority that several actors, such as Cagney, with whom Keighley made some of his greatest pictures, found off-putting. After a twenty-year run in motion pictures, Keighley’s confident, formal articulation became the voice of CBS Radio’s “Lux Radio Theater” from 1945 to 1955. Keighley led the production north from Hollywood to Bidwell Park in Chico, California. The picturesque location harbored the same romanticized idealism of Howard Pyle’s original stories. Filming began in the fall of 1937 as the colors began to turn, so usually green leaves were changing to brown, and foliage lacked the fullness of summer. Vegetable dye sprayed on the dying leaves gave the appearance of a brighter, green, blooming forest. Additional material such as ornamentally attractive rocks and trees, sometimes artificial, furthered the stagelike and storybook appearance of Bidwell Park-turned-Sherwood. As soon as filming began, residents from Chico and nearby cities began to claim their genealogical heritage to the original Sherwood Forest rabble. Clearly taken with the big-budget production setting down so close to their homes, area citizens announced themselves as descendants of Robin’s Merry Men. The production erected umerous massive tents to provide cast and crew with offices during the outdoor shoot, giving the case reprieve from the penetrating lights required for the Technicolor cameras. As a result, Bidwell Park became a “tent city.”

The production was fraught with problems, some of them propelled by its star. Early into the shoot, Flynn, wearing a shaggy wig as part of his costume, demanded another wig to be created, one more comfortable and visually appealing. At first, the studio denied his requests until he wrote Wallis explaining that the damned thing was scratchy. Wallis had a vast fondness for Flynn, so he wrote the art department to construct the actor a new wig. Reshoots were thankfully avoidable as Robin Hood often wears his trademark pointed hat throughout most of the picture, covering any inconsistencies in wig design. Keighley worked on The Adventures of Robin Hood for two months until Warner Bros. replaced him with Michael Curtiz in November 1937. Variety claimed that the switch occurred due to Keighley’s reported fatigue and poor health. Film historians maintain that the studio found the director’s pace, both onscreen and behind the camera, too slow. Inexperienced in massive action-heavy swordplay epics such as this, Keighley’s resumé to that point primarily consisted of comedies, musicals, and gangster pictures. Keighley specialized in capturing dramatic or solemn moments, like the scene where Marian plays guest to the band of Merry Men that just robbed her, and she sees that Robin Hood seeks to make the lives of his people livable again. Keighley’s expertise in dramatic architecture shines in delicate moments like this one, and his replacement could create images and action proficiently sparkle with the flash of striking swords and the launching of arrows.

The Hungarian-born director Michael Curtiz stands as one of early Hollywood’s most impressive talents behind the camera. A skilled journeyman, Curtiz made whatever project Warner Bros. asked him to, but he did so with such craftsmanship that his body of work remains a revelation. Everything from comedies to swashbuckling adventures, from romances to Westerns, from musicals to war pictures—Curtiz did it all. His best-known works include Casablanca, Mildred Pierce, Yankee Doodle Dandy, Dodge City, The Sea Wolf, Young Man with a Horn, and Angels with Dirty Faces. With Errol Flynn alone, Curtiz would make twelve films, even though the two hated each other. Curtiz staged dangerously authentic action scenes while harboring an intense personality and poor relationship with many actors (often resulting from the director’s thick Hungarian accent). For instance, the title of David Niven’s autobiography, Bring on the Empty Horses, originates from the set of The Charge of the Light Brigade, when Curtiz demanded that someone “bring on the empty horses,” meaning horses without riders. For the massive charge scene in Brigade, hundreds of horses depicted running at full speed into battle are shown falling from cannon fire or gunshot wounds; to achieve this effect, Curtiz used tripwires to topple the animals, breaking their legs or killing many of them in the process. After Flynn reported his actions to the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, Congress passed new laws to prevent animal cruelty on film sets. In other cases, Curtiz’s drive for authenticity risked the lives of his actors.

On the set of The Sea Hawk, Curtiz reportedly uttered some offensive comment to Flynn, who responded by wrapping his hands around the director’s throat. No one knows exactly what Curtiz said to the actor to incite the outburst, but the actor refused to work with him from then on. Though he had to endure another picture with Curtiz already in development, the Western Santa Fe Trail, Flynn made sure the experience was a living hell for all involved. Flynn manufactured numerous pranks, including walking off the set after a two-hour shot set-up and even driving his car in the distance during a range scene (which was left in the picture). Flynn’s contempt for Curtiz could not bear another collaboration. After a string of pictures together in the early forties, their next picture together was to be They Died with Their Boots On; however, after Flynn protested, Curtiz was replaced by director Raoul Walsh. Flynn and Walsh developed a close kinship and would make seven pictures together. Michael Curtiz was an impeccable artist despite his faults, which becomes apparent when viewing The Adventures of Robin Hood. Using his established visual tricks, the director marks the picture with his undeniable stamp of excellence. His traditionally fluid camerawork remains remarkably unrestricted by the lumbering Technicolor cameras; his action scenes are shot with an incredible flow. Keighley and Curtiz used Tony Gaudio and Sol Polito, respectively, as cinematographers. Gaudio’s scenes are delicate and painterly, while Polito applies electric violence that shimmers in Technicolor.

Curtiz’s use of shadow throughout his career exists as his most visually inventive flourish. From Rocky Sullivan’s expressive shadow stalking him to the electric chair in Angels with Dirty Faces to the ten-foot silhouettes of Indian women dancing in The Charge of the Light Brigade, Curtiz often made the most interesting characters in a given scene background shadows. In The Adventures of Robin Hood, during the final swordfight between Robin and Sir Guy, Curtiz moves the combatants into the foreground and projects their massive dueling shadows onto a rear pillar. The actors disappear, but their profiles fight; the image proved so monumental, Curtiz used it again on the Errol Flynn pirate epic The Sea Hawk. Curtiz’s obsession with action and Flynn’s physical prowess met each other halfway. Attempting to show up Douglas Fairbanks, Flynn did most of his own stunts; however, he would later claim he did all of his own stunts as Fairbanks once did. The actor’s costars and the film’s crew acknowledge that he completed ninety-nine percent of his stunt work, but just as Fairbanks, for truly death-defying acts, a stuntman donned Robin Hood’s green tights. Flynn could, however, be accredited to his handling of both sword and longbow throughout combat sequences.

Fencing instructor Fred Cavens choreographed the sword fights and duels, as he did on Flynn pictures Captain Blood and The Sea Hawk. Cavens originated a now-popular approach that blends swordplay with dialogue. As Robin and Sir Guy go face-to-face with their broadswords, they also clash words: Sir Guy growls, “You’ve come to Nottingham once too often!” Blades clink. And then Robin Hood replies with a confident but determined smile, “When this is over, my friend, there’ll be no need for me to come again!” This jibe exchange made action scenes humorous and suspenseful, stressing the hero’s ability to out-quip the villain. Cavens also brought a delicacy to the violence of sword fighting; his duelists always seem to be dancing or advancing at one another to a high-tempo rhythm. Because he choreographs scenes with such speed and brutality beyond other scenes of filmic swordplay from the period (the film stock is sped up slightly during battle scenes), Cavens’ approach insists upon thorough planning and fierce execution. Candlesticks, tables, and various other props are placed so that the actors can cut them down or smash them during the battle, making the fight seem random, though it is anything but. Cavens taught Flynn his legendary swashbuckling skills on Captain Blood. They would support the actor through his peak adventurer roles, until his last great swashbuckler performance in Adventures of Don Juan (1948).

World-famous archer Howard Hill taught Flynn to use a longbow, but Hill’s talent also afforded the film’s impressive archery sequences arresting realism. Hill constructed the film’s arrows using a specialized fletching that created a distinct Thwish! sound for the arrows zinging. When coordinating the archery tournament filmed at Busch Gardens, Hill’s longbow accuracy accomplished the scene where Robin Hood splits a competitor’s arrow in half (though the split arrow was likely bamboo, allowing for an easier break). Hill also constructed a method for a convincing arrow kill: stuntmen wore steel plates against their bodies, with balsam wood on top of that. Live arrows fired by Hill struck them and were stopped by the metal plate. Arrows appeared to stick into the victim’s body thanks to the balsam. Without Hill’s presence on the picture, The Adventures of Robin Hood would have relied on the then-popular solution of string-guided arrows, the strings usually visible on film. Instead, Hill supplied an authenticity that would be impossible in today’s productions—no contemporary insurance company would cover a film where live arrows are shot at actors. While still in production, Flynn reportedly killed a bobcat with a single arrow while hunting; however, the truth to that story is questionable. Flynn did develop into an impressive archer under Hill’s instruction. Later in his life, Flynn continued to be an avid hunter with his longbow. Both outdoorsmen, Flynn and Hill remained friends for years after working together.

After photography wrapped, Warner Bros. asked composer Erich Wolfgang Korngold, who at that point had written several scores for the studio, to write and conduct the music for their new film. Korngold, in Austria orchestrating an opera, turned down the offer. This was early 1938, and Nazi Germany had begun its string of invasions across Europe. However, just before the Anschluss, Korngold left Europe to take Warner’s offer, making sure that he, his son, and his parents were on a train (the very last one) out of Austria before the Nazi invasion force prevented him from leaving. The Adventures of Robin Hood literally saved Korngold’s life and the lives of his family members. Perhaps his deliverance propelled his ensuing work because this film’s score is one of the composer’s best. During quieter scenes or rowdy clashes, Korngold matches the key of an actor’s voice with individual notes; the effect produces a harmonious synchronization between dialogue and the composed voice. Korngold even inserts subtext into an early scene where Robin and Marian discuss the injustice of Prince John’s forces, a conversation solely about political travesties. The composer plays a light, passionate score, alluding to the burgeoning romance between the two main characters. Though they discuss impersonal matters, Korngold’s score tells his audience they are falling in love. His melodies resist association with typical 1930s scores as, all through the picture, the music transports the viewer to the storybook presentation of a Medieval England illustrated in Pyle’s texts. In addition to this film, Korngold also scored the Curtiz-Flynn collaborations Captain Blood, The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex, and The Sea Hawk.

When the production wrapped with an inflated budget of more than 2 million dollars, which made The Adventures of Robin Hood Hollywood’s most expensive picture produced up to 1938, the filmmakers had reasonable apprehension. Forecasted at around $1.6 million, the extra $400,000 could have made four or more individual pictures at that time. However, upon its May 14 release date later that year, all uneasiness about the film’s cost disappeared as audiences flocked to cinemas to see the grand Technicolor adventure. Thomas McNulty’s biography The Life and Career of Errol Flynn points out that the film appealed to escapist appetites familiar among 1930s audiences, even to a “democratic sense of fair play President Franklin Roosevelt was touting with his New Deal.” Much of Flynn’s Robin Hood dialogue is laden with democratic principles, speaking to a sense of equality and evenness in the world that did not exist during the time (nor now) but that people hoped for. As suggested above, the film also presented a heroic answer to the dictatorial influence sweeping across Europe. By offering the famed story of Robin Hood in 1938, Warner Bros. made a statement against Nazism that contradicted the isolationist and noninterventionist U.S. government’s stance on Hitler’s authoritarianism and dehumanization in Europe.

While acquiring over $4 million at the box office in an age when ticket costs were pocket change, the film received praise from audiences and critics alike. In 1938, Frank S. Nugent of the New York Times said the film is “a richly produced, bravely bedecked, romantic and colorful show, it leaps boldly to the forefront of this year’s best.” And even today, Roger Ebert includes the film into his “Great Movies” essays, commenting on the brilliant straightforwardness of the picture: “When Robin and Marian look in each other’s eyes and confess their love, they do it without edge, without spin, without arch poetry. The movie knows when to be simple.” In subsequent years, the picture received re-releases into cinemas, once again reviving audiences with love for this irony-free, genuine classic. Though The Adventures of Robin Hood was nominated, Frank Capra’s You Can’t Take It with You took home the Best Picture Oscar at the 1939 Academy Awards. Nonetheless, the film earned three helpings of just desserts: Carl Jules Weyl won for Best Art Direction; Ralph Dawson won for Best Film Editing; Erich Wolfgang Korngold won for his elegant score.

Under contract with Warner Bros., and given the film’s substantial profit-reaping blockbuster status, Errol Flynn was understandably upset over his low pay, dictated by his contract. Before the film’s release, Flynn was a meager star; nevertheless, the picture’s stellar business assured that future roles would payout for the actor, particularly of Robin Hood variety. Swashbuckling efforts like The Sea Hawk remained the star’s greatest hits. Over the next decade, Flynn’s onscreen persona included war pictures and romances, comedies, and dramas. The actor could handle more dramatic roles if allowed and yet was rarely given a chance, ironically, because of his greatest success. One of the few exceptions remains Gentleman Jim, where Flynn plays the agile boxer, Jim Corbett. A wholly separate Errol Flynn appears before the humbled John L. Sullivan (Ward Bond), who approaches Flynn’s Corbett at the end of that picture. Flynn shows dignified humanity, unlike any of his other roles. In his autobiography, Flynn notes Gentleman Jim as his personal favorite of his own performances. Memorable Flynn appearances materialize throughout his career in various forms. He plays a sympathetic George Armstrong Custer in They Died with Their Boots On, archetypal Western heroes in Dodge City and Virginia City, and even a French criminal in the underrated Uncertain Glory. His talent for the quick wit of screwball humor was evident in Four’s a Crowd, the one time Flynn would act in a comedy during his prime.

But again and again, Flynn begged Warner for alternative roles. Regardless of his success, Flynn would forever be limited to playing heroes. Possibly the one fault of The Adventures of Robin Hood is that the studio never allowed him to bud into the dexterous actor he could be because of its popularity. In the years to follow, his flagrant alcoholism, morphine habit, and self-punishing lifestyle aged him dramatically, so that ten years after his performance as Robin Hood, his body was struggling to keep up with his spirit. Finally, in 1947, Flynn’s contract with Warner was renewed, allowing him loan-out privileges to other studios. Flynn gave a most dignified performance in That Forsythe Woman for MGM, where the actor reveals his surprising competence for gravitas and emotional depth. By the early 1950s, Flynn’s contract with Warner Bros. ended. Struggling to finance independent pictures, he resorted to television appearances to pay the bills. As luck would have it, the actor’s best later roles came when he played caricatures of himself: often sad, aged drunks. Darryl F. Zanuck contacted Flynn for a supporting role in 1957’s The Sun Also Rises; Flynn proves himself worthy of acting Hemingway, stealing every scene he shares with Tyrone Power and Ava Gardner. The following year, Warner’s film Too Much, Too Soon had Flynn playing his longtime friend and likewise drunk actor John Barrymore, a man whose end sorrowfully foreshadowed Flynn’s.

After years of abusing his body with alcohol, women, and drugs, the actor died of a heart attack in 1959 at 50. When he died, doctors said that his worn 50-year-old body could have been mistaken for someone in their seventies. Even still, he went much too early for his kind of Hollywood legend. In the following years, those attempting to rethink Robin Hood would receive the same response: “He’s no Flynn.” Even today, the Douglas Fairbanks version Warner producers worried over possibly staining their chances for box office gold is now all but forgotten next to The Adventures of Robin Hood. The legendary character has been revisited by actors such as Sean Connery, John Cleese, Patrick Bergin, Kevin Costner, and even Daffy Duck, but Flynn’s performance overshadows them all. Proof of this came in 1949 when Warner’s “Merrie Melodies” short Rabbit Hood featured Bugs Bunny gallivanting around Chuck Jones’ cartoon Sherwood Forest. Spliced inside this ‘toon was the brief sequence from The Adventures of Robin Hood where Flynn swings in on a vine, cleverly edited to look like he is welcoming Bugs to Sherwood. Even Warner cartoonists knew better than to try and create a cartoon Robin Hood.

Every succeeding attempt to retell the Robin Hood fable fails in a way The Adventures of Robin Hood never does. The closest contender came in 1991 with Kevin Reynolds’ Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, a box office smash that critics spurned but audiences loved. The ineffectively costumed Kevin Costner stars, his British accent wavering between scenes in a film with as much lustrous beauty as a landfill. Tarnished with typical 1990s action scenes and an end-credits song by Bryan Adams (whose melody plays throughout the film), Reynolds’ Robin Hood is dated by the 1990s, to be sure. Like Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, the Walt Disney cartoon Robin Hood is marked by time, with 1970s folk music and humor. The 1976 revisionist film entitled Robin and Marian, starring Sean Connery and Audrey Hepburn in the title roles, portrayed the hero and his bride spoiled by time, reflecting the post-Vietnam innocence-lost attitude prevalent in mid-1970s motion pictures. More recently, Russell Crowe offered a rustic version of the hero in Ridley Scott’s epic Robin Hood, a film continuously and unfairly dismissed in the canon of great Robin Hood films. In almost every case where England’s arrow-shooting champion shows up in a film, the story echoes the particular society’s positions and feelings. The legend transforms as political conditions change, audience interests shift, or as the storyteller requires.

Somewhat taken for granted over the years as “just an adventure film,” The Adventures of Robin Hood remains timeless. It has since received praise from Hollywood legends such as Maid Marian herself, Olivia de Havilland. In an interview for Turner Classic Movies, De Havilland said that in the mid-1950s that she rewatched the picture. All at once, realizing what a fine film it was, she debated writing Flynn a letter telling him how proud he should be that he personified Robin Hood so perfectly. But, alas, she never wrote that letter. Flynn died two weeks later. Though he resented being cast as offshoots of Robin Hood throughout the latter part of his career, if Flynn were alive today, one can imagine him looking back at his performance as Robin Hood, or at the film as a whole, both often imitated yet still unmatched, and proudly reflecting on his legacy.

The Adventures of Robin Hood remains ageless, undemanding in the most marvelous of ways, and rich with effervescent filmmaking and performances. Producer Hal B. Wallis wanted sheer entertainment; his success allowed audiences to embrace, and still welcome today, what continues to be the most enjoyable prestige picture ever produced by the Golden Age of Hollywood or otherwise. Hatched from classic literature, folklore, and children’s books, the film refuses anything less than a universal audience: everyone will find something to love about The Adventures of Robin Hood. It embodies storybook pageantry from the literary opening to the fairytale ending, wisping audiences away into a romantic fantasy. Errol Flynn dashingly stands with fists on hips and fights with a playful bluster, shooting arrows like an expert, all the while charming us with his smile and back-bending laugh. The cast enchants Sherwood Forest, disappearing into the pages of a vast and impressive cinematic storybook. The entire picture blasts from the screen in Technicolor iridescence, its level of visual beauty, rarely matched in film history, described best by the original publicity squib: “Only the rainbow can duplicate its brilliance!” More fitting words were never written by a Hollywood marketing department.

Bibliography:

Basten, Fred E. Glorious Technicolor: The Movies’ Magic Rainbow. Easton Studio Press, 2005.

Flynn, Errol. My Wicked Wicked Ways: The Autobiography of Errol Flynn. Bloomington, Ind.: Third Woman Press, 1987.

Haines, Richard W. Technicolor Movies: The History of Dye Transfer Printing. McFarland & Company, 2003.

Harmetz, Aljean. Round Up the Usual Suspects: The Making of “Casablanca.” Orion Publishing Co, 1993.

Kalmus, Herbert. “Technicolor Adventures in Cinemaland,” Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, December 1938.

McNulty, Thomas. Errol Flynn: The Life and Career. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2004.

Robertson, James C.. The Casablanca Man: The Cinema of Michael Curtiz. London; New York: Routledge, 1993.

Rosenzweig, Sidney. Casablanca and Other Major Films of Michael Curtiz. Ann Arbor, Mich.: UMI Research Press, 1982.

Schatz, Thomas. The Genius of the System: Hollywood Filmmaking in the Studio Era. New York: Pantheon, 1988.

Schickel, Richard. The Men who made the movies: interviews with Frank Capra, George Cukor, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, Vincente Minnelli, King Vidor, Raoul Walsh, and William A. Wellman. New York: Atheneum, 1975.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review