The Definitives

The Abyss

Essay by Brian Eggert |

The purest expression of James Cameron’s artistic sensibilities, technical fanaticism, and thematic obsessions lies in The Abyss. As with most of his films, Cameron’s 1989 feature deploys extensive formal wizardry and a breakneck momentum in service of a high-tech extravaganza. The film’s bold and unconventional methods bolster themes that critique masculine violence and duplicitous institutions; it also valorizes female intuition, yearns for peace, and encourages harmony between humanity and the natural world. But unlike the director’s more actionized scenarios in the Terminator and Avatar franchises, the film doesn’t contradict itself by sensationalizing or glamorizing violence. While indulging his fascination with genre, engineering, and undersea technology, which preoccupy much of his filmography, Cameron’s story confronts humanity with global destruction by a superior species. And while his moving commentary draws from Atomic Age science fiction, its astounding presentation remains incomparable in terms of sheer scope and realism. No other underwater film compares. Cameron maintains that the shoot was his most difficult; it’s undoubtedly his most risky. Even today, it remains among the most technically ambitious productions in film history. Doubtlessly, nothing like it will ever be attempted again. But even as The Abyss is Cameron’s least successful film in terms of profits—a bar he usually sets to record-breaking heights—the film negotiates his recurrent themes and lifelong fixations with more effort and sensitivity than any other in his career.

The Abyss is about water and its mysteries. Water would be an enduring source of creativity for Cameron, evidenced in Titanic (1997), his submersible expeditions, and Avatar: The Way of Water (2022). Cameron’s interest in water began in childhood. He grew up in Chippawa, Ontario, and had an early interest in science and the arts as a child. He was just as skilled in both—a wunderkind, really. He read science fiction stories voraciously and dreamed of writing and illustrating a sci-fi novel before graphic novels became popular. Living within walking distance of Niagara Falls, the future director developed a fascination with water, especially the ocean, implanted by French oceanographer Jacques Cousteau’s television documentaries. As a child, he even equated the ocean’s depths to an alien world ripe for exploration. Eventually, Cameron convinced his father—who wanted his son to be an engineer and didn’t understand the boy’s interest in art and fantasy—to enroll him in a scuba class at a nearby YMCA. The instructor taught harsh lessons about safety in the manner of military-brand harassment training, where the instructor tampers with the diver’s equipment to test how well they can improvise underwater. The training style, which is no longer in practice due to the danger it presents, saved Cameron’s life while filming The Abyss. He has since logged hundreds of hours of underwater diving and in submersibles.

His only greater passion than water became filmmaking, an interest implanted upon seeing Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey in 1968. The experience, not to mention the vertigo that prompted him to vomit on the curb outside the theater afterward, left him reeling from its existential questions. He also became curious about how Kubrick put such wonderful images on the screen and went out to find a book about how he made the film. Cameron was like that as a kid—he would learn or experience something, and then it would become a preoccupation. For instance, because of his top marks in science courses and interest in Cousteau, he was invited to attend a series of lectures by commercial diver Frank Falejczyk in Buffalo, New York. The lecturer demonstrated an experiment involving liquid oxygen, which would allow divers to handle the pressure on deep dives better. The experiment ultimately failed in practical applications, but the idea stuck with Cameron, then seventeen, who went home and started writing the short story that would be the basis for The Abyss. Though, the short story hardly resembles the film’s narrative. It follows a group of researchers who use liquid breathing equipment to explore the Caribbean Sea’s deepest point, the Cayman Trough. A succession of divers goes down, but none of them returns. Finally, the last man goes after them, experiences something like elation, and in that, succumbs to a psychosis of the deep. While the short story doesn’t resemble the eventual film, it echoes the Friedrich Nietzsche quote that opens the Special Edition version (and was removed from the theatrical release): “…when you look long into an abyss, the abyss also looks into you.”

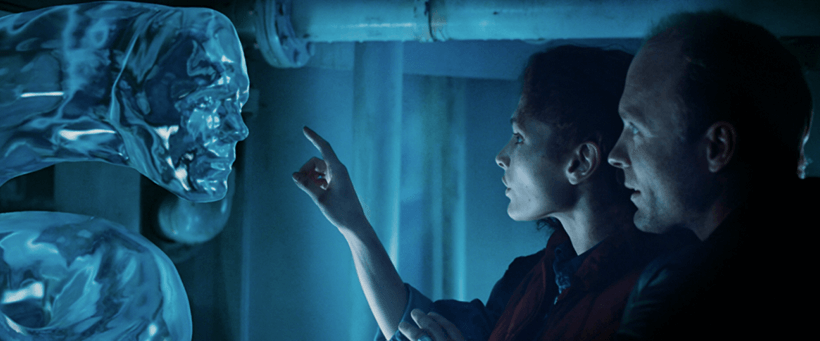

The term refers to the literal abyss in the Cayman Trough, but it also refers to the theoretical abyss of the unknown; the potential for every person to have an abyss inside them, capable of untold horrors; and the vast, black “bottomless pit” of death. The film’s story involves a prototype deep-sea oil drilling rig called Deepcore and its crew of drillers led by foreman Virgil “Bud” Brigman (Ed Harris). Echoing the same blue-collar quality of the cast from Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979), the crew doesn’t wear uniforms and blasts Linda Ronstadt’s “Willin’” on the job. Their workhorse dynamic is interrupted when their bosses at Benthic Petroleum, communicating from a topside ship that feeds air and electricity to Deepcore through an umbilical line, presses Bud’s crew into helping a Navy SEAL team investigate a nearby American nuclear submarine downed by a mysterious underwater presence, which military intelligence assumes is a Soviet submersible. The mission will be headed by Lt. Coffey (Michael Biehn). Add to this the arrival of Deepcore’s designer and Bud’s soon-to-be ex-wife, Lindsey (Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio), who doesn’t hold back her anger about the Navy seizing her station. While on a dive to collect the warhead, Lindsey sees something unexplained in the water. She believes an intelligent lifeform inhabits the abyss—a mysterious population of NTIs (Non-Terrestrial Intelligences). Coffey and Navy intelligence believe it’s a new Soviet threat and prepare for the worst, accelerating what might become a new Cuban Missile Crisis. Eventually, Lindsey comes face-to-face with an ethereal, bioluminescent creature that resembles a humanoid butterfly with large, round eyes that Cameron described as conveying “a cold, dispassionate wisdom without malice.”

The Abyss could have been several different films under a less ambitious screenwriter and director. One story involves a military operation to retrieve the nuclear warhead from the downed submarine and neutralize the perceived alien threat, recalling a similar theme in Cameron’s Aliens (1986), wherein militaristic orders conflict with more humanist concerns. Another story involves the oil-drilling crew at the bottom of the ocean, racing for survival when a hurricane dislodges the lifeline that provides them with fresh air and electricity, requiring practical solutions. The last story involves the underwater crew making first contact with an alien race, and the Navy responding with fear and paranoia, while Lindsey responds with an open heart. The aliens eventually present an ultimatum to humanity in response to its rampant history of violence and current rising tensions that could lead to World War III, raising vast tidal waves that promise to wipe out everything unless humankind changes its ways. Cameron blends these ingredients with some of his usual themes, including a critique of opportunistic corporate entities, a censure of the military that so often frames itself as a protective institution but more often perpetuates violence, and a humanist message about the importance of peace and preserving unique life. Cameron told an interviewer, “It’s a very positive, hopeful film with a message—that we have to change if we’re to survive as a species.”

In thematic terms, The Abyss is Cameron’s answer to socially conscious science-fiction films that emerged from Hollywood during the Atomic Age. In his book Seeing Is Believing, about this era of Hollywood’s sci-fi films, Peter Biskind wrote about a contingent of left-wing science fiction, such as Robert Wise’s The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), which demonstrated a political fear of “the center and the right, but the alien was neutral or benevolent, which is to say, these films tried to defuse the paranoia towards the Other.” Wise’s film features a UFO arriving in Washington D.C. to deliver an ultimatum: either humanity ceases its violence and development of increasingly deadly weapons, or an intergalactic federation of worlds will consider us a risk and destroy the planet. In such films, Earth’s human cultures are shown to be primitive, reactionary, and violent; its leaders paranoid from the Cold War; and its valued institutions, such as the military and free market corporations, are portrayed unflatteringly, suggesting there’s something corrupt at the heart of our sociopolitical infrastructure. The Abyss follows this structure to the letter. “The original goal of the film was to tell a story of a kind of apocalypse in which we are judged by a superior race,” Cameron wrote in 1992. “And [we are] found to be worthy of salvation because of a single average man, an Everyman, who somehow represents that which is good in us: the capacity for love measured by the willingness for self-sacrifice.”

Cameron took on The Abyss as a passion project after his smash hit Aliens, encouraged by his then-new wife and professional partner, Gale Ann Hurd, who suggested Cameron explore the short story he wrote as a teen. Meanwhile, she went off to develop Alien Nation (1988) for Fox, and their separate projects caused a fissure in their relationship. Cameron worked this personal conflict into his screenplay with the fractured marriage between Bud and Lindsey, resulting in some of his best and most complex character work. Before principal photography began, Cameron and Hurd would be divorced, but Hurd still produced The Abyss. No one else in Hollywood would have trusted Cameron’s ambitions and instincts tobring an unrivaled authenticity to underwater filming. He would set aside the usual Hollywood tricks, such as shooting dry-for-wet on a soundstage or using trained divers to replace his actors. Cameron also ruled out shooting in the ocean. No one in Hollywood liked doing water shoots; they led to countless technical problems, presented untold dangers for the cast and crew, and their unpredictable conditions could inflate a budget fast. Cameron told Starburst magazine, “If I couldn’t do what 2001 did for science fiction films taking place in space, if I didn’t feel I could do that with the underwater arena, I didn’t want to make the movie.” He resolved to use real actors in underwater conditions that no one had attempted before or since. The actors would have to become trained and certified divers, performing their own stunts and dives, but that was just for starters. Cameron expected the most of everyone; he pushed himself just as hard, often putting himself at more risk than anyone else on the set.

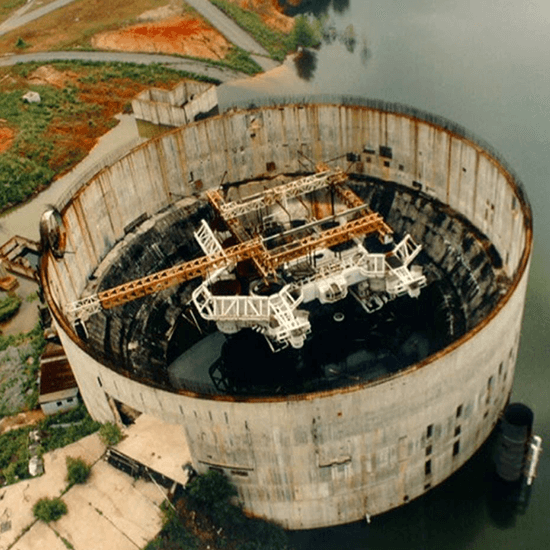

Shooting The Abyss was an act of Cameron’s signature brand of defiance and determination in the face of impossibility. “I like doing things I know others can’t,” Cameron told author Rebecca Keegan. To accomplish this, he tapped Al Giddings, the cinematographer and former competitive swimmer who shot the authentic diving scenes in The Deep (1977), to serve as director of photography. The production would be located at the Cherokee Nuclear Power Station outside of the somewhat isolated city of Gaffney, South Carolina. Duke Power spent nearly $700 million on the site’s construction before abandoning the project due to unpredictable economic factors. Drive-in mogul Earl Owensby had purchased the site with the intention of building a movie studio. When he heard about Cameron’s scouting of underwater locales in the Caribbean and large tanks in Europe, he invited the director to the unfinished plant, complete with warehouses and leftover machinery. There, Cameron saw the giant concrete cylinder designed to hold a nuclear reactor, with unfinished walls several feet thick and eighty feet high. Almost instantly, he knew this would be his production’s shooting location. But first, there were engineering challenges, such as installing gigantic pumps, filters, and heating units to keep the water warm enough to swim in and clear enough to shoot in. After their alterations, Cameron would have two massive tanks, one reaching depths of 55 feet and holding 7.5 million gallons of water, the other with 2.5 million gallons. The water came unfiltered from a nearby lake, requiring chlorine treatments that bleached hair and left burns on the cast and crew.

The production assaulted the actors, who mostly performed their own stunts in watery conditions. In one sequence, Cameron had Ed Harris—cast against the studio’s wishes (they wanted a marquee name such as Harrison Ford or Mel Gibson)—and two other actors running in cold, knee-high water away from 50,000 gallons rushing at them from behind. Sequences like this were common and required almost an hour between takes so the crew could pump out the water and prepare the stage for another onslaught. Over forty percent of the footage was shot underwater. “I knew this was going to be a hard shoot,” Cameron told Fantasy Zone in 1989. “But even I had no idea just how hard. I don’t ever want to go through this again.” Moreover, the demanding production required the development of state-of-the-art technology that didn’t exist before The Abyss, including functional submersibles, ROVs (remotely operated vehicles), and an air-filling station so divers wouldn’t have to return to the surface to replenish their supply. Cameron also needed helmets that supplied air yet clearly showed the actors’ faces. Western Space and Marine built a bespoke helmet designed by artist Ron Cobb, complete with a communication system for the divers and actors to record dialogue and receive direction from Cameron. The helmets also included a breathing apparatus built into the helmet, whereas most diving helmets featured a regulator that went in the wearer’s mouth. There were few props in the production. All the vital equipment had to be functional in case of an emergency, while also delivering the look Cameron wanted. At the time, production designer Les Dilley called the shoot “the most technically advanced piece of filmmaking ever.”

While creating movie magic on a daily basis and solving the problems of a highly technical shoot, the crew had to solve engineering problems, such as the tank rupturing and almost emptying due to an unpressurized filtration pipe. Every day featured similar challenges, leading to speculation among writers such as Ian Nathan that the entire production was an excuse for Cameron to test his aptitudes for science and engineering. But he had help. The director’s brother, Mike, a mechanical engineer, developed an apparatus called the SeaWasp that allowed the camera to move dynamically while underwater. Many of these developments would be used outside of The Abyss and movie industry. The production built a massive tarp to cover the tank to convey the blackness of the two-thousand-foot depth; it eventually ripped, requiring the production to shoot at night. Shooting in dark water, the production developed unique underwater lights that would capture the low light, which would go on to be used by NASA and other Hollywood productions. Few of these innovations mattered to Twentieth Century Fox, which approved the project with a budget of $40 million and a 140-day shooting schedule, neither of which would be met. Shooting expenses were upwards of $250,000 a day, prompting the studio’s head to visit. Cameron reacted to the suits with hostility, holding one executive over a diving platform and putting another in a diving helmet with no oxygen, demonstrating that his production was dangerous and their presence was an unwelcome distraction.

While the shoot remained under strict secrecy, it also solidified Cameron’s reputation as a taskmaster on his sets. He expected his cast and crew to be tough, and he endeavored to be a leader like Bud. But he told Keegan, “I found it personally hard to lead that way.” The crew called the set “The Abuse” instead of The Abyss. Harris, the actor who had the most perilous shots, came close to being a “goner” more than once. He wept one night after almost drowning during a 40-foot swim without oxygen equipment. When Harris needed air during one take, the so-called rescue angel who was meant to bring it got stuck, and the backup mistakenly gave Harris the regulator upside-down, filling his lungs with water. The situation looked dire until the angel corrected the error, leaving Harris shaken but alive. Cameron wanted to try the take again, but Harris refused. Even the dry sets on Deepcore left actors damp and cold, shivering between takes. Mastrantonio left the set during the emotional CPR scene—requiring her to wear painful contacts to dilate her eye, appear open-shirted with her breasts exposed, and be worked over physically by Harris. After the second take, when the camera ran out of film, she shouted “We’re not animals here!” and left the set. Cameron insisted in subsequent interviews that his team took every safety precaution to keep the cast and crew alive, yet when they complained about the conditions, he was known to call people “wussies” or reply with quips like “I’m letting you breathe, what more do you want?” Whether spending two-and-a-half hours each day beneath the water’s surface in a potentially deadly, claustrophobic environment for several months would keep them sane was another matter and not Cameron’s concern.

After all, he was undergoing the same trials. Although Cameron pushed his cast and crew, he also led by example. The Abyss often shot for eighteen hours a day, at the end of which the director, who was spending the most time underwater, would have to hover ten feet under the surface for an hour to depressurize. To make use of the time, he installed a monitor in a control room so he could watch dailies while he waited. But his helmet proved so heavy that he made the crew turn the monitor so he could review dailies upside-down without the strain on his neck. The most alarming story from the set involved Cameron running out of air because an AD forgot to give the director his requested low-air warning beforehand. Cameron nearly drowned after a rescue diver gave him a faulty regulator that filled his lungs with water. Believing Cameron was panicking instead of downing, the diver held him in place, requiring the director to call on his harassment training and punch the diver to escape his grip and make for the surface. An hour after his near-death incident, he was back directing. But as harsh as he could be, he also cared about preserving life. When a lab rat almost drowned during the scene where a SEAL demonstrates the liquid oxygen technology (in the film, the rats actually breathe the stuff), Cameron gave the rodent CPR and saved it. He kept the rat as a pet. Elsewhere, Harris doesn’t breathe liquid oxygen; he was forced to pretend to breathe it while holding his breath during difficult takes.

Although much of what the viewer sees in The Abyss is real, the production demanded plenty of special effects as well, including miniatures, puppets to make the underwater aliens, rear-projection screens, and green-screen work. Yet, the film is also a breakthrough for CGI. Cameron’s use of the unproven technology was a major gamble on a production where science and realism remained at the forefront. At that time, digital filmmaking technology had been around since the 1970s, such as the computer-controlled cameras that were used to seamlessly integrate miniatures and special effects in Star Wars (1977). A few years later, in 1982, Industrial Light & Magic developed a method of creating computer-generated images for Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan and TRON. Other minor examples appeared throughout the 1980s, but Cameron’s experimentation with CGI for the “pseudopod” water tentacle in The Abyss became a vital testing ground for digital animation, marking a leap forward that inspired him to develop the liquid metal T-1000 from Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991). ILM’s Dennis Muren, John Bruno, Hoyt Yeatman, and Dennis Skotak toiled to get the water-based tentacle right. It had to be as convincing as everything else in the film; otherwise, there would be no sense of wonder when it appeared. Scholar Robin Baker noted that it took six months of “intensive work and constant checking with the director on the form and realism required” for the sequence. Cameron demanded that its surface undulate like in a swimming pool and appear as lifelike as its surroundings inside the rig. It remains a singular and convincing effect.

Although the CGI tentacle became a test that would lead to Cameron’s more advanced effects on Terminator 2: Judgment Day, The Abyss also boasts one impressive set piece after another beyond the computer-generated breakthrough. Cameron is famous for his domino-effect plotting and action, and his methods are never more thrilling than in The Abyss. Coffey’s thoughtless commitment to orders finds him taking a mini-sub to recover a nuclear warhead from the downed submarine in case of a threat from the NTIs. This leaves the crew incapable of uncoupling the umbilical when a hurricane arrives topside. When the umbilical crane breaks off and falls down the nearby trench, it pulls Deepcore to the trough’s edge and cuts off the station’s fresh air supply. Coffey’s paranoia about the NTIs, exacerbated by his high-pressure nervous syndrome—a detail wisely suggested by Biehn, who performs the tremors with jittery, frightening energy—incites him to fasten the warhead to a submersible that will head into the trench, where the NTIs presumably live. But Lindsey heads out to stop him, leading to a breathless mini-sub chase that ends with Coffey falling into the trench, where pressure causes his sub to implode in a horrific shot. Trapped in a mini-sub, Lindsey and Bud have only one suit and thus one way out: Lindsey must go into hypothermia and drown, and Bud must drag her back and revive her. All of this momentum leads to the film’s most powerful scene: Bud and crew must save Lindsey, and his guard drops, allowing for a raw outpouring of desperation and love. Cameron has built momentum from causal effects into his films before, but never have his films rippled with such a thrilling and emotional consequence.

The dramatic wallop of The Abyss grows from the outset, when Cameron establishes a layered portrait of a seemingly by-name-only marriage, anchored by two nuanced performances from Harris and Mastrantonio. Though she is Deepcore’s designer, Lindsey arrives aboard a man’s world, surrounded by rugged and jocular types, including Coffey, who jokes at the idea of calling her “Sir.” She immediately clashes with Bud and questions his leadership choices and the technical running of her rig. Bud responds almost flirtatiously, trying to mediate, but she replies with barbs. He responds by tossing his wedding ring, which he still wears, much to Lindsey’s surprise, into a chemical toilet. He almost immediately regrets this, prompting him to recover the ring, leaving his hand stained blue for the remaining runtime—a visual reminder that it meant so much to him. This is despite Bud’s language about Lindsey, classifying her as a “bitch” driven by emotion instead of his rugged practicality, conveying the general attitude toward women in the film. Bud thinks hurricanes should be named after women, and his oft-used remark, “Keep your pantyhose on,” suggests a gendered understanding that women are impatient, irrationally so. To be sure, later, Bud calls her willingness to “go on a gut feeling” about the NTIs “hysterical.” Yet, Bud is more intuitive than he may seem, as shown in his empathetic leadership style that contrasts Coffey’s hard-nosed approach. The language and gender politics in Cameron’s script have a distinct purpose, however; they establish a faulty male logic that perpetuates aggression, while the only person intuitive enough to recognize the NTIs as a non-threat is Lindsey, who admits to maintaining a “cast-iron bitch” persona to survive in a patriarchal society.

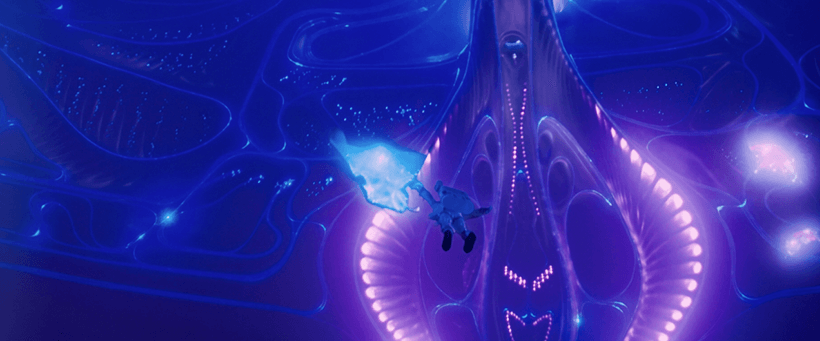

In a recurring theme throughout Cameron’s work, ranging from The Terminator (1984) to the Avatar movies, women are saviors, built with the emotional intelligence and rationality necessary to preserve life, fight for ethical imperatives, and greet the unknown with open arms. Lindsey most closely recalls Sigourney Weaver’s exobiologist character in Avatar in that sense—both work for a company bent on exploiting a natural resource yet set those directives aside when faced with a new and beautiful lifeform. While Bud’s crew and the SEALs question her belief that the NTIs are real and not a threat, she pleads with her husband: “You have to look with better eyes than that.” If Bud can’t see it Lindsey’s way at first, he eventually changes after accepting a one-way mission into the trench to disarm the nuke sent by Coffey to destroy the NTIs. He disarms the bomb, exchanges a few heartfelt text exchanges with Lindsey, and resolves to die in the abyss. But the NTIs appear to him, take his hand, and guide him to their massive bioluminescent station, with Alan Silvestri’s resounding choral score implanting an overwhelming sense of wonder and discovery. Traversing vaginal canals that resemble the psychedelic journey into the Beyond in Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, Bud is literally and figuratively born again on the other side, having emerged from a liquid womb to breathe for the first time, like a newborn child, with a new outlook that fully aligns with Lindsey—a more sensitive, feminine view of intuition over aggression and paranoia. It is this worldview, spied in the final text exchange between Bud and Lindsey, that convinces the NTIs to draw back their tidal wave and not eradicate humanity. In the end, the reconciliation occurs not just between the surface and the NTIs, but also Bud and Lindsey, making The Abyss a tale of remarriage.

Moreover, The Abyss remains the only Cameron film to effectively achieve its intended message about nonviolence without making violence an overtly central component to the narrative—a bout between Bud and Coffey and mini-sub chase notwithstanding. Cameron implants similar themes in T2 and Avatar (2009), though they hardly resonate given how those stories rely on violent thrills, shootouts, and scopic scenes of war. The director’s critiques of the patriarchy and military dogmatism in The Abyss also rival those in Aliens, with Coffey personifying a paranoid and aggressive military presence, not to mention an ineffectual patriarchal figure who nearly destroys the world with his aggression. Indeed, in Cameron’s films, scholar Joe Abbott notes that, “One detects in them a textual politics that offers effective ideological criticism by vilifying what America’s capitalist ideology recognizes for the most part as revered institutions.” The Abyss shows that it’s not the company or the military that saves the day; instead, sensitive individuals who experience love and do not feel threatened by the Unknown convince the NTIs that humanity is worth saving. They even bring Deepcore topside, thus resolving their oxygen shortage. If these myriad solutions register as unbelievable or convenient, they nonetheless reflect Cameron’s rather sentimental presence amid a sea of cynical and ironic perspectives.

After all the technical innovations and challenges, Cameron’s production cost $60 million and grossed around $90 million. The successful but not overwhelming performance no doubt suffered from the string of fast-tracked, similarly themed underwater thrillers designed by competing studios to beat the latest from the filmmaker of The Terminator and Aliens to the punch. Although none of Cameron’s undersea imitators in 1989 would achieve the same technical bravado or thematic weight as The Abyss, some remain entertaining. The first of them, DeepStar Six, found Mario Kassar and Andrew G. Vajna’s production company Carolco Pictures in league with lowbrow horror maestro Sean S. Cunningham (Friday the 13th, 1980), who helms a diverting C-grade yarn about an undersea station that awakens a sea monster. Faring better was Leviathan, a B-grade production that borrows liberally from Alien and The Thing (1982). But its considerable production values and solid ensemble cast (Peter Weller, Amanda Pays, Ernie Hudson, Richard Crenna, et al.), supported by a Jerry Goldsmith score, Stan Winston special effects, and designs by frequent Cameron collaborator Ron Cobb, make it worthwhile. Other direct-to-video releases from 1989, including Roger Corman’s production Lords of the Deep and the cheapie The Evil Below, dealt with similar ideas. Most of these preemptive imitators lost money, though they’re remembered for contributing to an odd phenomenon of underwater movies in 1989.

When The Abyss debuted in August, the reviews were mostly positive, if somewhat tepid after the raves about Aliens, no doubt owing to the hasty cuts Cameron made during post-production based on a test audience’s reactions. The director screened the full-length version before completing the visual effects on the tidal wave sequence, and so predictably, the test audience listed the unfinished wave portions as the scenes they “liked least.” Cameron intended these moments, along with the conclusion where the NTI ship rises from the deep to the surface, to have the same awe factor as Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). When they didn’t, he chose to remove them. The studio didn’t mind. Barry Diller, the head of Fox, told Cameron it was “too much movie.” What is more, Cameron told Starburst magazine, “I was never quite satisfied with the visual reality of the tidal wave.” He also noted that going to the surface takes the viewer out Deepcore, robbing the narrative of its persistent claustrophobic quality—a fair criticism. But the tidal wave sequence still nagged at Cameron after the film’s underwhelming theatrical run. Akin to the fever dream that inspired his vision for The Terminator, Cameron had recurring nightmares of a giant wave coming toward him.

In 1992, Cameron went back and reinserted the scenes, restoring his preferred “Special Edition” to its full-length glory, the version he prefers today. Cameron later admitted, “I made cuts to the film that I should have made.” He told Keegan that he learned a valuable lesson to “never, ever preview a movie with unfinished effects.” Running 22 minutes longer than the theatrical cut, the director’s version has since become the standard, even earning a glowing reassessment in 1992 from critics and a re-release into theaters in 2023. But Cameron never got water out of his system. In the next decade, he made the ultimate oceanic disaster-romance with Titanic, the longstanding “highest-grossing movie of all time.” He later bowed Avatar: The Way of Water. Both resulted in major technical advancements for water-based productions. Outside of his directorial projects, in 2012, Cameron took a one-person submersible, which he helped design, to the bottom of the Mariana Trench, some 35,000 feet down, where he glides around in the dark, looking amid the blackness for signs of life. Detailed in the 2014 documentary Deepsea Challenge, Cameron’s journey found only anthropoids, not NTIs. Nevertheless, what other filmmaker would risk being “chummed into a meat cloud” to explore their curiosity?

While The Abyss may distill James Cameron’s authorial sensibilities to their purest form, it does not embrace his interest in the straight action and gun violence found in nearly all of his other work. But those absences better communicate Cameron’s enduring theme of nonviolence, even though escapism remains a regular component of his cinema. Even so, the story remains his most deeply felt next to Titanic, his most humanist, and his most technically ambitious overall. The production, both behind the scenes and onscreen, allowed the director to explore his interest in engineering, the ocean, extra-terrestrial worlds, and several sci-fi concepts. And whereas his work became increasingly dependent on computers in the decades to follow, the tactility of The Abyss, combined with its single sequence of CGI, also marked a transition point for a director who would take the digital tool to new heights. Beyond its achievements in filmmaking and creating a wholly convincing world, the film, no matter how many times one sees it, always manages to conjure resounding feelings about the importance of peace, the intuitive perception of women, and the rocky but no less affecting bond between Bud and Lindsey. The Abyss is a sensation machine—a thrill ride with no shortage of technical bravado and unforgettable imagery, but it also reminds the audience that, at his core, Cameron is an earnest and warm storyteller.

(Note: This essay was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on March 27, 2024.)

Bibliography:

Abbott, Joe. “They Came from Beyond the Center: Ideology and Political Textuality in the Radical Science Fiction Films of James Cameron.” Literature/Film Quarterly, vol. 22, no. 1, 1994, pp. 21–27. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43796613. Accessed 1 March 2024.

Abbott, Stacey. “Final Frontiers: Computer-Generated Imagery and the Science Fiction Film.” Science Fiction Studies, vol. 33, no. 1, 2006, pp. 89–108. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4241410. Accessed 1 March 2024.

Althusser, Louis. “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses,” Lenin and Philosophy and other Essays. Monthly Review, 1971, pp. 166.

Baker, Robin. “Computer Technology and Special Effects in Contemporary Cinema.” Future Visions: New Technologies of the Screen. Ed. Philip Hayward and Tana Wollen. British Film Institute, 1993, pp. 31-45.

Belton, John. “Digital 3D Cinema: Digital Cinema’s Missing Novelty Phase.” Film History, vol. 24, no. 2, 2012, pp. 187–95. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2979/filmhistory.24.2.187. Accessed 1 March 2024.

Biskind, Peter. Seeing Is Believing: How Hollywood Taught Us to Stop Worrying and Love the Fifties. Pantheon, 1983.

Blair, Ian. “Underwater in The Abyss”. Starlog Magazine. No. 146, September 1989.

Cornea, Christine. Science Fiction Cinema: Between Fantasy and Reality. Rutgers University Press, 2007.

Elefante-Gordon, Juanita. “James Cameron: In Depth.” Fantasy Zone, #2, November 1989.

Jones, Alan. “Life’s Abyss and Then You Dive.” STARBURST Magazine, #287, June 2002.

Keegan, Rebecca. The Futurist: The Life and Films of James Cameron. Three Rivers Press, 2009.

Mikulec, Sven. “‘The Abyss’: James Cameron’s Exploration of Humanity and Love in the Heart of the Ocean.” Cinephilia & Beyond. N.D. https://cinephiliabeyond.org/the-abyss-james-camerons-exploration-of-humanity-and-love-in-the-heart-of-the-ocean/. Accessed 8 March 2024.

Nathan, Ian. James Cameron: A Retrospective. Palazzo Editions, 2012.

“Under Pressure: Making The Abyss.” The Abyss, Special Ed. DVD, Twentieth Century Fox, 1993.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review