The Definitives

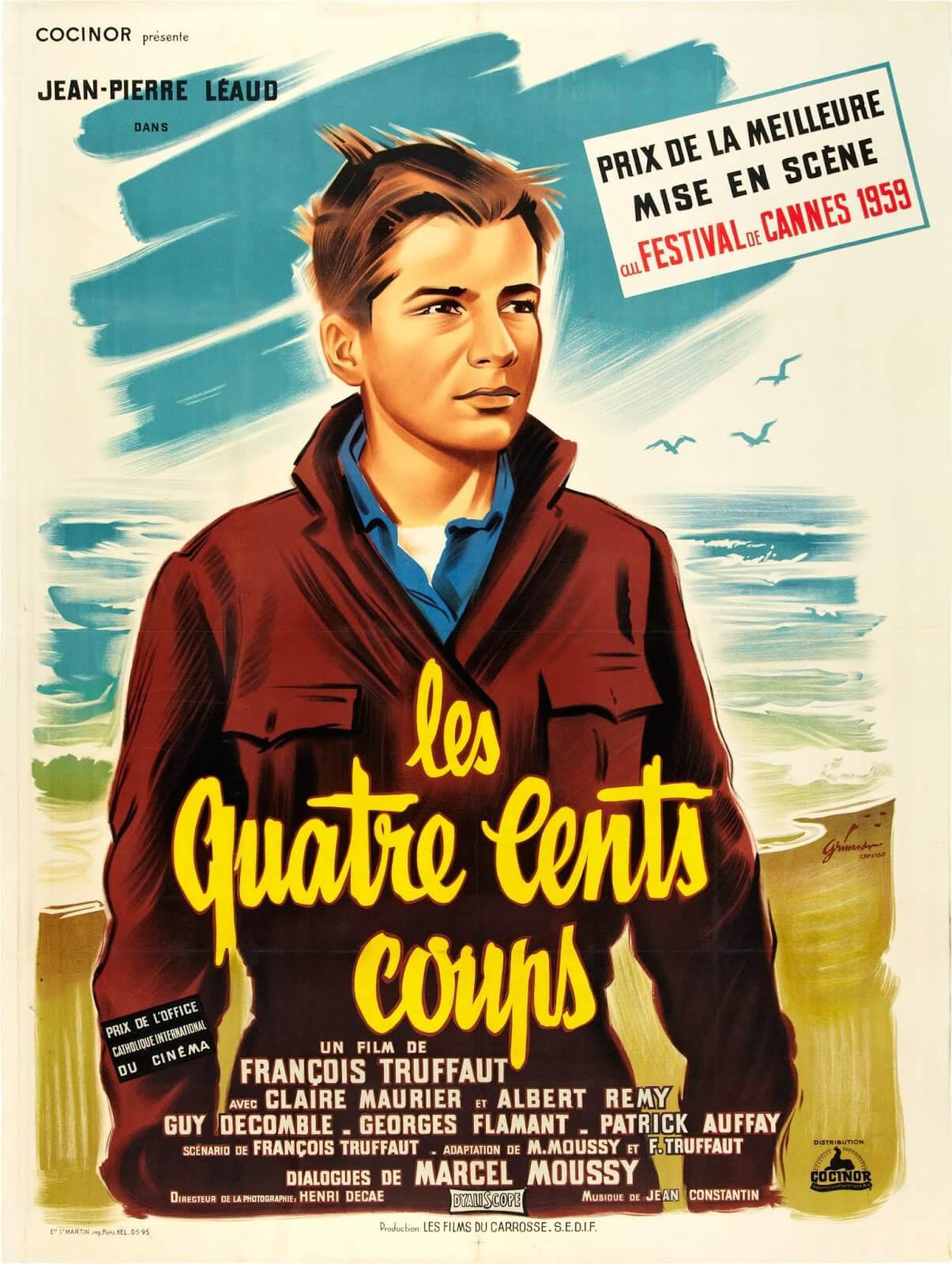

The 400 Blows

Essay by Brian Eggert |

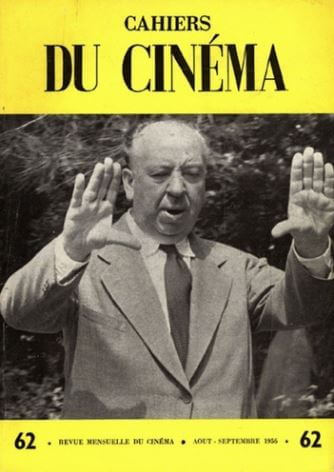

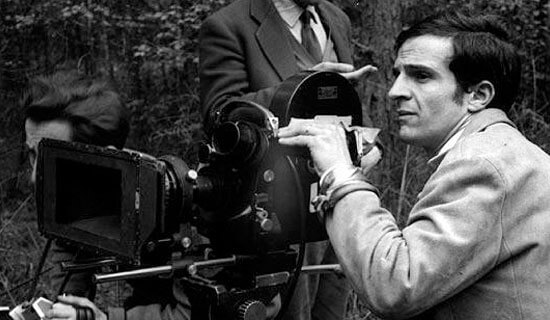

François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows is a landmark of the French New Wave movement and, in broader terms, and perhaps more importantly, the emergence of auteur filmmaking. Truffaut’s film was among the first, and easily the most well received, to implement ideals outlined by a group of upstart film critics writing in the film journal Cahiers du cinéma, most of which would become New Wave filmmakers. Along with Jean-Luc Godard, Éric Rohmer, Jacques Rivette, and Claude Chabrol, Truffaut’s harsh criticism demanded new styles and themes for the artistically dwindling French “Tradition of Quality” in cinema, which had become mired in polished, yet stodgy historical dramas and dull literary adaptations maintained by an older generation of directors. With his 1959 full-length debut, Truffaut practiced what he had so ardently preached in New Wave avowals. Through his autobiographical construct, the enduring character Antoine Doinel, a young outcast played by Jean-Pierre Léaud, Truffaut would explore his own childhood in a deeply tender demonstration of how the film director is also the film author.

Today, Truffaut’s film may seem rather common, being a coming-of-age tale in which a youth, propelled by his disdain for his parents and the general misery of being a teenager, sets out to run amok, gets himself into serious trouble, and resolves to run away. Indeed, the title in French, Les Quatre cents coups, comes from an expression meaning to “raise hell”. To fully appreciate the dynamism of Truffaut’s film, however, one must place themselves in the mid-1950s in France, where the complacency of the film industry led to ruthless attacks from the writers in Cahiers du cinéma. By 1958 and even more so in the subsequent year, the first films by New Wave directors, many of them critics-turned-filmmakers, had begun to appear. Chabrol’s Le Beau Serge (1958) and Les Cousins (1959), Louis Malle’s The Lovers (1958), Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima mon amour (1959), and Godard’s Breathless (1960) showed the first signs that a change to the French film industry had arrived. The New Wave would come to represent the dividing movement between classical and modern filmmaking.

Even among film historians, the French New Wave (or nouvelle vague) remains a varying collection of names and dates and films, many of them debatable within the movement depending on the respective historian’s definition of the movement. As a result, the name itself is a blanket term, to be used in an open sense. Most agree that the New Wave began in 1958 and came to an end, as much as such a thing can, in 1964. And most agree that the undisputed origins of the New Wave were developed by critics of Cahiers du cinéma. Founded in 1951 by André Bazin and Jacques Doniol-Valcroze, in association with Léonide Keigel and Joseph-Marie Lo Duca, the magazine reinvented principles of film theory and criticism and, largely from monumental writings by Bazin and Truffaut, launched the notion of what Andrew Sarris would later call “the auteur theory”—the notion that more than a studio or writer or producer, the director is the author of a film. In their exploration of this notion, Cahiers du cinéma writers reassessed the careers of Hollywood directors Anthony Mann, Samuel Fuller, Howard Hawks, Nicholas Ray, and Alfred Hitchcock (Truffaut himself published the seminal interview with Hitchcock on his work), while also bringing renewed enthusiasm to the French greats Jean Renoir (The Rules of the Game) and Max Ophüls (The Earrings of Madame de…), among others.

Even among film historians, the French New Wave (or nouvelle vague) remains a varying collection of names and dates and films, many of them debatable within the movement depending on the respective historian’s definition of the movement. As a result, the name itself is a blanket term, to be used in an open sense. Most agree that the New Wave began in 1958 and came to an end, as much as such a thing can, in 1964. And most agree that the undisputed origins of the New Wave were developed by critics of Cahiers du cinéma. Founded in 1951 by André Bazin and Jacques Doniol-Valcroze, in association with Léonide Keigel and Joseph-Marie Lo Duca, the magazine reinvented principles of film theory and criticism and, largely from monumental writings by Bazin and Truffaut, launched the notion of what Andrew Sarris would later call “the auteur theory”—the notion that more than a studio or writer or producer, the director is the author of a film. In their exploration of this notion, Cahiers du cinéma writers reassessed the careers of Hollywood directors Anthony Mann, Samuel Fuller, Howard Hawks, Nicholas Ray, and Alfred Hitchcock (Truffaut himself published the seminal interview with Hitchcock on his work), while also bringing renewed enthusiasm to the French greats Jean Renoir (The Rules of the Game) and Max Ophüls (The Earrings of Madame de…), among others.

In doing this, Cahiers du cinéma authors noted how their own national cinema had become bogged down by the old ways. But this was not an awareness exclusive to the film industry; a series of economic, societal, and technological factors aligned to spawn a new creative consciousness that found its most profound result in the cinematic art form. France had experienced a cultural resurgence in the years following World War II, with a national effort to rebuild, most noticeably in the automobile and television industries. All things “old” soon signified the non-newness that France’s youth culture rebelled against. During this uprising of sorts, with growing markets all around, the film industry experienced what Pierre Billard, the editor for the magazine Cinéma, called “the depletion of inspiration, sterilization of subject matter, and static aesthetic conditions”. With a few rare exceptions, including the works of Jacques Tati, Robert Bresson, and Jacques Becker, tragically, cinema, the highest of modern art forms, had become a most apparent symptom of a cultural downturn. As a reaction to this, the Cahiers du cinéma authors called for less labored, less industry-standard filmmaking. And when the industry failed to listen, the unruly critics became filmmakers themselves.

Their method would contrast what had become commonplace in the industry, drawing heavily from filmic sources inside Hollywood, Italian Neorealism, and 1930s French filmmakers like Renoir. Instead of heavy polish and high production values, New Wave directors would shoot fast and cheap at real-life locations; their subjects would move outside of the typical norms and often involve lower middle-class youth (it was, after all, a movement driven by lower middle-class youths). The booming industry would only help their cause, as suddenly minor producers could invest in a cheap film that would, in turn, produce a modest profit and favorable critical response; although, it helped that many of the critics in French film journals were or would soon be fellow filmmakers in full support of the New Wave movement. By 1959, as their movement surfaced and The 400 Blows was selected to represent France at the Cannes Film Festival, Godard, ever the iconoclast, rallied against his elder generation of directors in an issue of the journal Arts. He wrote, “Your camera movements are ugly because your subjects are bad, your casts act badly because your dialogue is worthless; in a word, you don’t know how to create cinema because you no longer even know what it is.” How appropriate then that, in spearheading a movement determined to raise so much hell, Truffaut’s aptly titled film mined the critic-turned-director’s own childhood experiences and delivered an affecting portrait of youth. In The 400 Blows, Truffaut’s camera movements are dynamic because his subject is impassioned, his cast acts wonderfully because the dialogue is either written by or acted by artists who have experienced the material; in a word, who better to create great cinema than someone who has lived and breathed it since his childhood?

Truffaut was born in Paris in 1932 to a mother of 19 and, as his birth certificate would read, a “father unknown”. His mother had originally wanted an abortion, but his grandmother convinced her otherwise (a detail given to Antoine in the film). Until 1942 when she died, Truffaut was raised by his grandmother and then, begrudgingly, went to live with his unstable mother and new stepfather. Determined to spend as much time away from home as possible, Truffaut found refuge in books and especially the cinema, sneaking into theaters or stealing to scrape enough money together to buy a ticket. By 1948, he had formed his own film-club and through his various contacts met Bazin, who helped Truffaut escape charges of desertion after he left the army. The deeply troubled Truffaut was in effect rescued by Bazin and fostered into a critic position at Cahiers du cinéma, in which he gained a reputation as a scathing reviewer. His many breakthrough articles included A Certain Tendency of the French Cinema, where he argued that the French film industry needed to be rejuvenated. As Bazin taught him film theory, Truffaut learned the practice of filmmaking from mentors like Roberto Rossellini and Jean Cocteau during on-set visits. Finally, after experimenting with two short films (Une Visite and Les Mistons), Truffaut set out to make his first feature-length film.

Truffaut was born in Paris in 1932 to a mother of 19 and, as his birth certificate would read, a “father unknown”. His mother had originally wanted an abortion, but his grandmother convinced her otherwise (a detail given to Antoine in the film). Until 1942 when she died, Truffaut was raised by his grandmother and then, begrudgingly, went to live with his unstable mother and new stepfather. Determined to spend as much time away from home as possible, Truffaut found refuge in books and especially the cinema, sneaking into theaters or stealing to scrape enough money together to buy a ticket. By 1948, he had formed his own film-club and through his various contacts met Bazin, who helped Truffaut escape charges of desertion after he left the army. The deeply troubled Truffaut was in effect rescued by Bazin and fostered into a critic position at Cahiers du cinéma, in which he gained a reputation as a scathing reviewer. His many breakthrough articles included A Certain Tendency of the French Cinema, where he argued that the French film industry needed to be rejuvenated. As Bazin taught him film theory, Truffaut learned the practice of filmmaking from mentors like Roberto Rossellini and Jean Cocteau during on-set visits. Finally, after experimenting with two short films (Une Visite and Les Mistons), Truffaut set out to make his first feature-length film.

Truffaut originally intended to make only a short film about an autobiographical character named Antoine Doinel, the name an ode to both Jean Renoir’s assistant Ginette Doynel and also Cahiers du cinéma co-founder Doniol-Valcroze. But after the success of his short films, his wife Madeline’s father agreed to fund Truffaut’s first feature in the spirit of familial prosperity, and production commenced with a budget of around $75,000 (the average budget for a French film at the time was $250,000). Truffaut hired screenwriter and novelist Marcel Moussy to flesh out the dialogue and narrative, as he wanted his film to be about more than “the life of François Truffaut”. As it turns out, it would be as much about actor Jean-Pierre Léaud. Out of upwards of sixty young actors who auditioned, Truffaut chose Léaud because he shared so much in common with the main character and therefore Truffaut himself. Both were anti-social outsiders who caused trouble and loved the cinema; Antoine Doinel would become a composite persona of both Truffaut and Léaud. Throughout shooting, Truffaut encouraged Léaud to improvise dialogue and put as much of himself into the role as possible, the result bringing a veracity to the performance and emotional consequence to the story. The production filmed on Parisian streets, in real apartment buildings, and in a school during Christmas vacation, avoiding the studio gloss Truffaut had so often censured. Tragically, Bazin died of his long suffered affliction with tuberculosis on the first day of shooting. Truffaut dedicated the film to his memory.

Drawn from events in his own life, Truffaut’s film finds Antoine living in a cramped apartment with his parents. His impatient mother (Claire Maurier) cannot be bothered with her troublesome teenager, and his moody stepfather (Albert Remy) goes from childish antics one moment to angrily demanding to know where his Michelin Guide disappeared to the next. As they argue with each other in front of Antoine about suspecting each other’s infidelity, it becomes clear neither adult is fit for parenting. Yet, they are complicated characters both: she selfish yet full of guilt; he silly, suspicious, yet a decent enough man to marry a woman with an illegitimate son. At school, Antoine’s teacher (Guy Decombie) singles the boy out in class and assigns punishments designed to humiliate. And though it may seem like Antoine’s circumstances are utterly tragic, he is not without culpability. After all, he lies about not taking his stepfather’s Michelin Guide. When he fails to complete his homework one evening, the next day, he and his friend René (Patrick Auffay), a character named after Truffaut’s brother who died two months after being born, resolve to skip class for a day at the movies and the carnival.

On the way home, Antoine spots his mother kissing another man; their eyes abruptly meet and look away. The both of them caught—he playing hooky, she in her affair—they pretend not to have seen each other. When he returns to school, Antoine struggles to form a believable lie about why he missed class and, reeling from anger toward his mother, he claims that she died. Shocked, the teacher believes him, until Antoine’s parents arrive at school and, in addition to being scolded, he is labeled a liar in class. Knowing her affair caused Antoine to create such a lie, his mother showers him with affection at home, running him a bath and offering him money for an unspoken understanding of confidentiality. As a schoolboy, Truffaut once used the excuse that his father had been captured by the Nazis; when he later discovered that his biological father was a Jewish dentist, Truffaut’s lie proved eerily coincidental. A scene in Antoine’s classroom depicts a student struggling with his English lesson; he has trouble pronouncing “Where is the father?”—a question that echoes throughout the film. Truffaut’s fixation on absent parents, more specifically an absent father, becomes a recurrent theme flowing through The 400 Blows.

On the way home, Antoine spots his mother kissing another man; their eyes abruptly meet and look away. The both of them caught—he playing hooky, she in her affair—they pretend not to have seen each other. When he returns to school, Antoine struggles to form a believable lie about why he missed class and, reeling from anger toward his mother, he claims that she died. Shocked, the teacher believes him, until Antoine’s parents arrive at school and, in addition to being scolded, he is labeled a liar in class. Knowing her affair caused Antoine to create such a lie, his mother showers him with affection at home, running him a bath and offering him money for an unspoken understanding of confidentiality. As a schoolboy, Truffaut once used the excuse that his father had been captured by the Nazis; when he later discovered that his biological father was a Jewish dentist, Truffaut’s lie proved eerily coincidental. A scene in Antoine’s classroom depicts a student struggling with his English lesson; he has trouble pronouncing “Where is the father?”—a question that echoes throughout the film. Truffaut’s fixation on absent parents, more specifically an absent father, becomes a recurrent theme flowing through The 400 Blows.

It may be that Antoine’s behavior results from his lack of a fatherly presence, but Truffaut also depicts the world as an unfair place for the boy, who is punished as much for getting things right as he is for his misbehavior. When he turns in an essay, the teacher accuses him of plagiarism, although Antoine completed the assignment from memory in an inspired homage to Honoré de Balzac’s novel La Recherche de l’Absolu; he even keeps a shrine to Balzac in his room. Later, when his shrine catches fire, a family argument fires up too only to be quelled by a trip to the movies. Even so, getting in trouble for loving Balzac is the last straw. He runs away from home and finds refuge with René, whose parents are also non-present. The two boys drink and smoke and scrape-it-up on the city streets, and for a time enjoy their freedom, until they decide to steal and hawk Antoine’s stepfather’s typewriter from his office. When their attempt to sell the typewriter fails, Antoine is caught trying to return it. His parents have given up; they want him placed in a detention center for troubled youths, and in turn sign over their parental rights. Antoine spends the night in a cell surrounded by hoodlums and prostitutes, and then rides through the dark Paris streets in a paddy wagon that delivers him to a reform school where he will learn a trade. A 17-year-old Truffaut had experienced similar events in his life when his stepfather had him imprisoned due to several outstanding debts from starting a film club. Truffaut was left in prison for two nights (by French law, a father could imprison a disobedient son for up to six months), and afterward, he was interned in a juvenile detention center for a three-month stay. In his own prison, Antoine is interviewed by an anonymous psychologist who remains offscreen. Léaud improvised much of the dialogue in this sequence, which consists of one shot that uses lap dissolves to connect his responses. Here he admits knowing that, like Truffaut, he was supposed to be aborted, but also confesses to stealing money from the grandmother who defended his life. Antoine is not perfect.

Locked away, Antoine is visited by his mother, who tells him they had considered taking Antoine back—that is, until Antoine sent his stepfather a letter about his mother’s affair. Now she wants nothing to do with him. With no ties left, one day Antoine escapes the detention center and runs, in a long, cathartic tracking shot, to freedom. The indelible final image of the film zooms in on a freeze frame of Antoine, who has found his way to a beach. Interpretations about the meaning of this shot vary to a staggering degree. Some see it as a mug shot, confirming Antoine’s place in the world as a rebellious young hooligan. Others see it as the intransience of the onscreen character made into a filmic portrait, almost as though Truffaut knew the character and image would become iconic. Truffaut freezes on a moment where Antoine is between two worlds: his family and life’s history is behind him; before him are the limitlessness and possibility of the ocean. Yet, Antoine seems caught in the middle, plagued by his past and hopeful for the future. The ambiguity of this moment, and Léaud’s impenetrable expression, has the permanence and inscrutability of Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa.

Locked away, Antoine is visited by his mother, who tells him they had considered taking Antoine back—that is, until Antoine sent his stepfather a letter about his mother’s affair. Now she wants nothing to do with him. With no ties left, one day Antoine escapes the detention center and runs, in a long, cathartic tracking shot, to freedom. The indelible final image of the film zooms in on a freeze frame of Antoine, who has found his way to a beach. Interpretations about the meaning of this shot vary to a staggering degree. Some see it as a mug shot, confirming Antoine’s place in the world as a rebellious young hooligan. Others see it as the intransience of the onscreen character made into a filmic portrait, almost as though Truffaut knew the character and image would become iconic. Truffaut freezes on a moment where Antoine is between two worlds: his family and life’s history is behind him; before him are the limitlessness and possibility of the ocean. Yet, Antoine seems caught in the middle, plagued by his past and hopeful for the future. The ambiguity of this moment, and Léaud’s impenetrable expression, has the permanence and inscrutability of Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa.

That the ending resists a commentary on the film’s events defines it not as a progression narrative; rather, Truffaut offers a “slice of life” from Antoine’s perspective and emphasizes the director’s fascination with Italian Neorealism. But just as much as Truffaut strives for a realistic depiction of a lower class youth by shooting on location and with a certain dramatic dirge, he finds moments of joy in Antoine’s exploits with René, and appropriately shoots them with enlivened formal techniques. Consider the sequence that follows from a bird’s eye view as Antoine’s gym teacher leads a train of students on a jog through Paris; as the train hops along, students scamper off the line, and before long the gym teacher is leading only a few lingering students. Or consider the sequence where Antoine and René take the day off; Truffaut loses himself in filmic trickery just as Antoine loses himself in their escapades. The camerawork becomes elegant and fluid, the editing forms a loose relation between shots to evoke the day’s joyful chaos; and, at one point, Truffaut’s mobile camera takes us inside a spinning carnival ride for a zoetrope effect that becomes even more dizzying when the image turns upside-down. Such playful flourishes burst into the film’s most enjoyable and expressive sequence, only to be suddenly cut down when Antoine sees his mother kissing another man, a revelation neither Antoine nor the audience sees coming.

While other New Wave filmmakers, such as Godard, sought to take cinema into bumpy experimental realms, Truffaut remained true to the marriage of method and story through an auteur’s use of mise-en-scène. As a result of his accessibility, Truffaut would forever be regarded as the leader of the movement, proving that cinema could be rejuvenated through the connection between mode and subject. Although The 400 Blows was not the French New Wave’s first film, it was the first New Wave film to bring vast international attention to the movement. After winning a prize for Best Director at the Cannes Film Festival (it lost the Palme D’or to Marcel Camus’ Black Orpheus), the film went on to become one of France’s highest grossing releases of that year, validating both the movement and the filmmaker himself. Having resonated with French audiences, moviegoers the world over made the film a milestone of international cinema. Truffaut later received a nomination for Best Original Screenplay at the Academy Awards. More significantly for Truffaut and Léaud, the film and its protagonist begat a series of continuing adventures for Antoine Doinel, allowing both young men to work through their lifelong personal associations onscreen. Truffaut and Léaud followed The 400 Blows with the short film Antoine and Collette (1962), and then three feature-length sequels: the great Stolen Kisses (1968), the pleasant Bed and Board (1970), and the ostensible clip-show Love on the Run (1979). Truffaut and Léaud also made non-Doinel titles together, including Les deux Anglaises et le continent (1971) and Day for Night (1973), but neither were as successful as their Doinel pictures.

While other New Wave filmmakers, such as Godard, sought to take cinema into bumpy experimental realms, Truffaut remained true to the marriage of method and story through an auteur’s use of mise-en-scène. As a result of his accessibility, Truffaut would forever be regarded as the leader of the movement, proving that cinema could be rejuvenated through the connection between mode and subject. Although The 400 Blows was not the French New Wave’s first film, it was the first New Wave film to bring vast international attention to the movement. After winning a prize for Best Director at the Cannes Film Festival (it lost the Palme D’or to Marcel Camus’ Black Orpheus), the film went on to become one of France’s highest grossing releases of that year, validating both the movement and the filmmaker himself. Having resonated with French audiences, moviegoers the world over made the film a milestone of international cinema. Truffaut later received a nomination for Best Original Screenplay at the Academy Awards. More significantly for Truffaut and Léaud, the film and its protagonist begat a series of continuing adventures for Antoine Doinel, allowing both young men to work through their lifelong personal associations onscreen. Truffaut and Léaud followed The 400 Blows with the short film Antoine and Collette (1962), and then three feature-length sequels: the great Stolen Kisses (1968), the pleasant Bed and Board (1970), and the ostensible clip-show Love on the Run (1979). Truffaut and Léaud also made non-Doinel titles together, including Les deux Anglaises et le continent (1971) and Day for Night (1973), but neither were as successful as their Doinel pictures.

Each of the sequels has its virtues, but something about the open-endedness of The 400 Blows makes one wish Truffaut had allowed it to be a singular work, as the possibility contained within the film’s final shot remains one of the most compellingly equivocal yet moving images in all of cinema. Nevertheless, the film stands on its own, as does Truffaut and his monumentally important writings at the launch of the greater French New Wave. Along with Breathless, Truffaut’s debut is the work most often associated with the movement; his subsequent films Shoot the Piano Player (1960) and Jules and Jim (1962) would also become highlights of the New Wave. With a conspicuously assured hand, he realizes the kind of film that he and his fellow writers at Cahiers du cinéma had demanded for years. But more than any other film to emerge from within the New Wave, Truffaut’s enduring masterpiece transcends its specific cultural motivations and associations within the movement to become a film that pierces a widespread audience as much today as ever, accessing emotions from our adolescence that continue to feel universal and modern.

Bibliography:

Nupert, Richard. A History of the French New Wave. Second Edition. The University of Wisconsin Press, 2007.

Truffaut, François. The Films of My Life. Simon and Schuster, 1975.

Truffaut, François. “A certain tendency of the French cinema.” In: Movies and Methods. Edited by Bill Nichols. University of California Press, 1976.

Truffaut by Truffaut. Texts and documents compiled by Dominique Rabourdin; translated from the French by Robert Erich Wolf. Abrams, 1987.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review