The Definitives

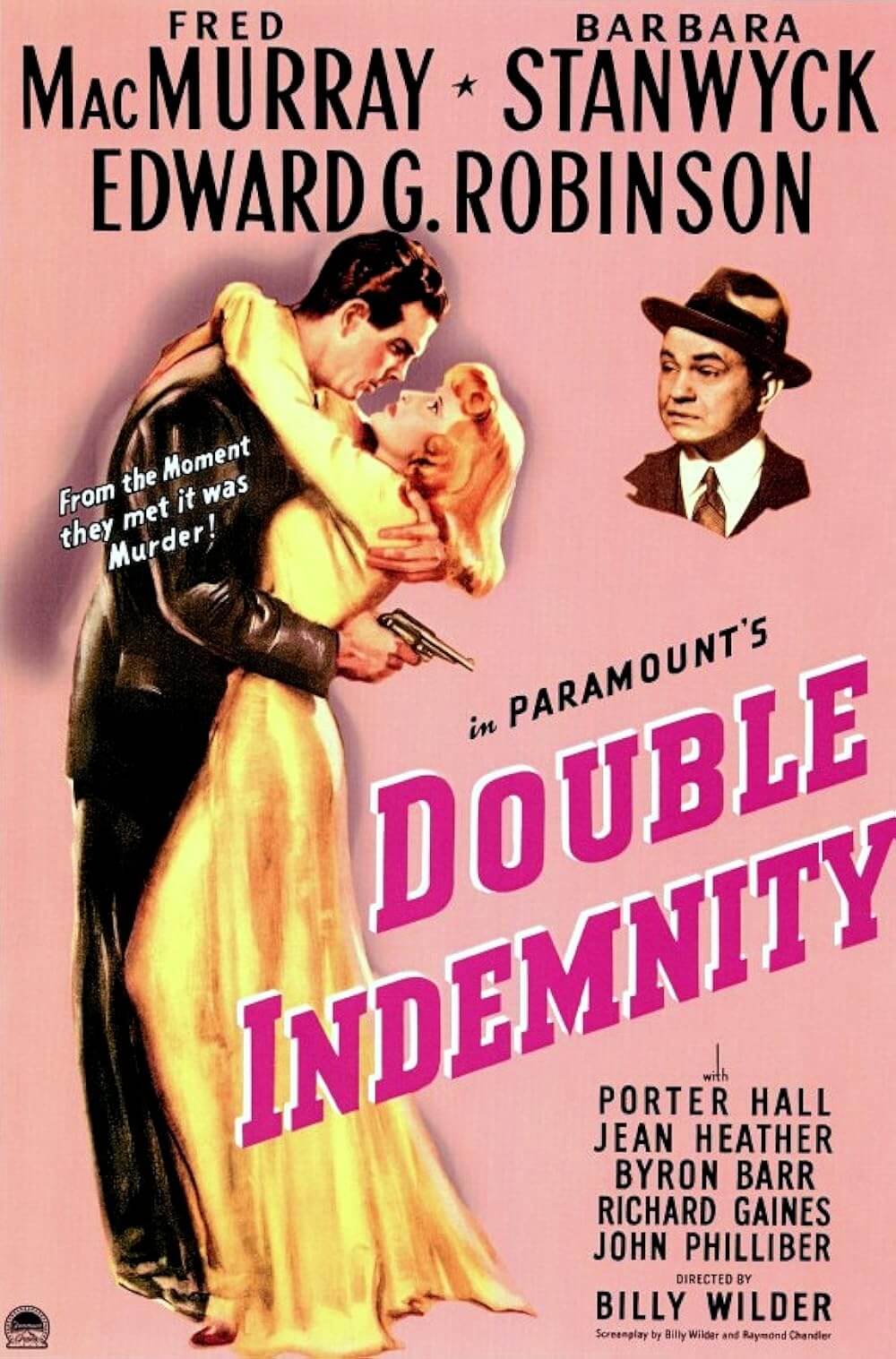

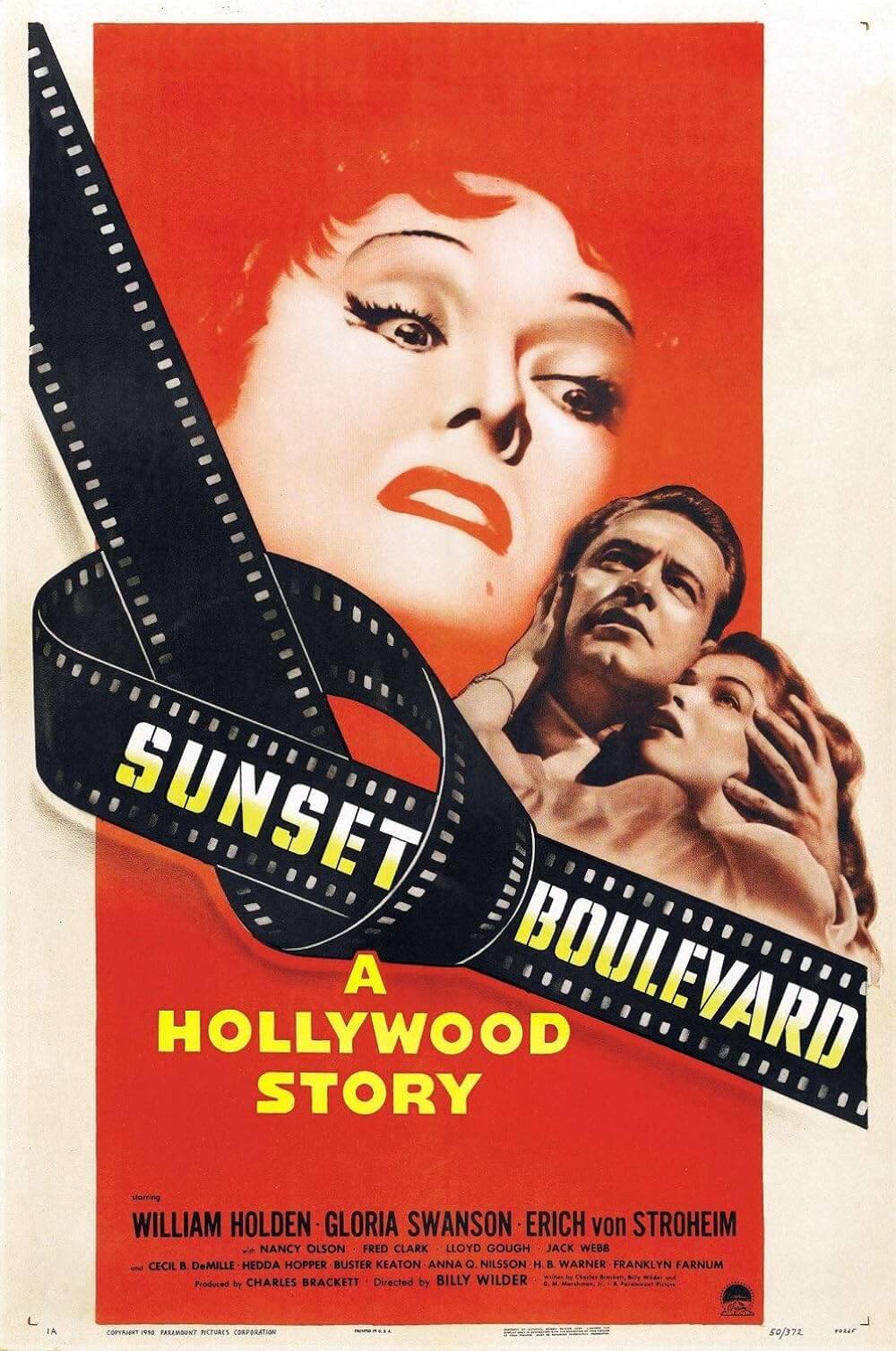

Sunset Boulevard (1950)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Disturbing yet bitterly funny, Sunset Blvd. stands as perhaps the greatest of all films about Hollywood. Some might call it a portrait of silent film stars unable to keep their careers going once talkies dominated the market. Others have argued it’s really about the countless unsuccessful would-be somebodies who are chewed up and spit out, or worse, found dead, because they’re not tough-skinned enough to make it in show business. Really though, it’s a warts-and-all portrait of Hollywood in all its unforgiving, ruthless glory. The film even uses real names of well-known actors and directors; real-life actors like Gloria Swanson and Erich von Stroheim, desperate for a role after fading from the limelight, play, quite scandalously, grotesque versions of themselves. After seeing the film in an early screening, MGM studio head Louis B. Mayer told the film’s director and co-writer Billy Wilder, “You have disgraced the industry that made and fed you! You should be tarred and feathered and run out of Hollywood!” When there were no reporters around to record the conversation, Mayer supposedly attacked the Jewish heritage of the Austrian-born Wilder, who had fled to Paris and then America after Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor in 1933, for coming to this country and taking advantage of the film industry that made him a success. Wilder’s response to Mayer perfectly summed up the director’s cynical attitude: “Go shit in your hat.”

Released in 1950, Sunset Boulevard (as it is most often written) has been saturated into cinematic pop-culture. The iconic line, “All right, Mr. De Mille, I’m ready for my close-up” loses most of its rather unsettling purpose out of context. Nevermind that former silent film star Norma Desmond, played by real-life silent film star Gloria Swanson, has killed for that close-up because her desire for the spotlight has driven her mad. Nevermind the implication that Tinseltown habitually discards its most treasured stars sometimes after a single bomb, turning those stars into washed-up, humbled, or forgotten relics. Returning to the film more than sixty-five years after its release, in an age where Hollywood commercialism is at its worst, Sunset Boulevard remains a scathing and vital work of satire. At least, Hollywood magnates such as Mayer would like you to believe the film is satire—that Norma Desmond’s low state has been exaggerated to darkly comic extremes. But Wilder incorporated enough truth into the film that when Hollywood went to see the film, they saw a mirrored reflection that was much uglier and stranger than they expected. In fact, Sunset Boulevard contains more truth than most of the top Hollywood brass was willing to tolerate. Though Wilder received accolades in other circles for his unconventional picture and the craft with which it was made, he received an equal amount of derision from his Hollywood contemporaries.

Narrating from beyond the grave, or swimming pool, struggling screenwriter Joe Gillis (William Holden) tells us how it all began. He was turned down for his latest spec script and narrowly ducking repo men after his past-due car when he turned into the driveway of a dilapidated mansion. He hides his car and, a moment later, finds himself ushered inside by a butler named Max (Erich von Stroheim). When Joe first meets his unsuspecting host, she’s donning sunglasses and a leopard print wrap around her hair. She thinks he’s there to build a child’s coffin for her pet chimp, which has died, its body beneath a blanket on a table, like an altar. Then he recognizes her. “I know your face,” he says. “You’re Norma Desmond. You used to be in silent pictures—you used to be big.” Norma (Gloria Swanson) replies, “I am big. It’s the pictures that got small.” If that response wasn’t enough, Joe says under his breath, “Uh-huh. I knew there was something wrong with them.” Norma has been planning a comeback with a script she’s written about Salome, that female icon of desire, who of course Norma feels she was born to play. Presenting himself as a hotshot writer, Joe offers his services to rewrite her script, and Norma agrees but demands he move in. She seems to know all about his failing career and money problems. No matter, he needs a place to live, so he accepts the offer, however odd it may be. He quickly becomes her plaything. She buys her new kept man clothes, gives him shelter, and entertains him. And when he rejects her pitiable pass at a New Years Eve party where he’s the sole guest, she tries to kill herself—a strategic way of exacting her power over him (when cinematographer John F. Seitz asked Wilder how he wanted the scene shot, the director replied, “Johnny, it’s the usual slashed-wrist shot”).

Narrating from beyond the grave, or swimming pool, struggling screenwriter Joe Gillis (William Holden) tells us how it all began. He was turned down for his latest spec script and narrowly ducking repo men after his past-due car when he turned into the driveway of a dilapidated mansion. He hides his car and, a moment later, finds himself ushered inside by a butler named Max (Erich von Stroheim). When Joe first meets his unsuspecting host, she’s donning sunglasses and a leopard print wrap around her hair. She thinks he’s there to build a child’s coffin for her pet chimp, which has died, its body beneath a blanket on a table, like an altar. Then he recognizes her. “I know your face,” he says. “You’re Norma Desmond. You used to be in silent pictures—you used to be big.” Norma (Gloria Swanson) replies, “I am big. It’s the pictures that got small.” If that response wasn’t enough, Joe says under his breath, “Uh-huh. I knew there was something wrong with them.” Norma has been planning a comeback with a script she’s written about Salome, that female icon of desire, who of course Norma feels she was born to play. Presenting himself as a hotshot writer, Joe offers his services to rewrite her script, and Norma agrees but demands he move in. She seems to know all about his failing career and money problems. No matter, he needs a place to live, so he accepts the offer, however odd it may be. He quickly becomes her plaything. She buys her new kept man clothes, gives him shelter, and entertains him. And when he rejects her pitiable pass at a New Years Eve party where he’s the sole guest, she tries to kill herself—a strategic way of exacting her power over him (when cinematographer John F. Seitz asked Wilder how he wanted the scene shot, the director replied, “Johnny, it’s the usual slashed-wrist shot”).

Still, Joe doesn’t give up his writing career, even if milking Norma for all she’s worth is a cushy gig. Alongside an attractive studio story editor, Betty Schaefer (Nancy Olson), with whom he falls in love, Joe begins a new script, working with Betty in the evening. Meanwhile, Norma and Joe’s Salome script has been sent to Paramount Pictures. Shortly thereafter, a studio assistant begins calling, seemingly about the script. Norma refuses to take the call—she’ll accept no less than Cecile B. DeMille himself calling. Finally, they visit the studio, where the old-timers around the lot who remember her from days past welcome her, showering her with much-lauded attention. DeMille, playing himself, wants nothing to do with her script but wants to prevent crushing the obviously deluded former starlet. That DeMille protects her is a symptom of Norma’s denial disease, encouraged the most by Max. For example, the studio was not calling about her script; instead, they wanted to rent her extravagant, hand-crafted automobile built in the 1920s. But Max and DeMille hide this from her, just as Max himself—who, as former director, made Norma and was her first of three husbands—writes her fan letters that prevent her from accepting the truth: That, as Joe remarks in his voiceover, she was “still waving to a parade that has long since passed her by.”

Humiliated for using Desmond the way he has, Joe despises himself so much for what he’s become that he refuses to run away with Betty, even though they’re in love. Worse, Norma threatens to disclose his dirty little secret to Betty, but her blackmail doesn’t work. Joe invites Betty to Norma’s mansion, where he reveals his situation. Betty doesn’t care, she just wants Joe. But he refuses to go. He doesn’t deserve Betty. With this, Joe turns on Norma and reveals the truth—that Paramount only wanted to rent her car, that Max has been writing her fan letters. He begins packing and announces he’s going home to Ohio. “No one ever leaves a star,” she says, a crazed look in her eyes. More crazed than usual, anyway. “That’s what makes one a star… The stars are ageless, aren’t they?” With that, Joe tries to run out, but Norma shoots him and his body falls into the pool. As police gather, Norma learns of the cameras downstairs, operated by reporters there to cover the murder. She has fully slipped away into an all-consuming denial fantasy. Max, helping the police, encourages Norma to shoot her big scene as a princess descending a staircase. Max directs the scene. He calls “Action!” to the media’s cameras and Norma makes her way down, the reporters and police frozen in place as she takes each step. When she reaches the bottom, she thanks everyone for being a part of her new film. “I promise you, I’ll never desert you again, because after ‘Salome’ we’ll make another picture and another picture… This is my life, it always will be. Nothing else. Just us, the cameras, and those wonderful people out there in the dark…” Finally, she looks into the camera and says, “All right, Mr. DeMille, I’m ready for my close-up.” Then Norma approaches us and fades into nothingness.

Wilder and his longtime writing partner Charles Brackett had conceived a story about a once-beautiful and talented silent film star whose celebrity faded with the Jazz Age. As much as their main character, their tale would portray Hollywood in all of its potential ugliness. Wilder and Brackett began writing in 1948 and were determined to keep their screenplay top-secret “due to the peculiar nature of the project,” working under the title A Can of Beans. The very concept of Brackett and Wilder’s early work was instantly strange. The original idea about a silent film star in then-contemporary Hollywood originated some years earlier, when Wilder had scribbled an idea onto a scrap of paper: “Silent picture star commits murder. When they arrest her she sees the newsreel cameras and thinks she is back in the movies.” The bizarre story begins with its protagonist, a writer and the film’s narrator, dead in a swimming pool. The character spins a yarn about his own death, which involves several Hollywood hopefuls and former stars, all trying to make a comeback or make it big for the first time. With just a kernel of an idea and one-third a screenplay finished, Brackett and Wilder consulted friend and fellow card-player D. M. Marshman, Jr., a former film critic for Time magazine. Along with most of the writing, Marshman also contributed the most eyebrow-raising component of Sunset Boulevard by suggesting the silent film star get involved with a younger man.

As the film’s protracted writing process continued, Brackett and Wilder had a particular list of actors they hoped to secure for the picture. Back when the concept was more comedic, Wilder wanted Mae West and Marlon Brando in the lead roles. But as the story turned in a strange kind of horror-comedy with the addition of Marshman, Wilder decided he wanted the young method actor Montgomery Clift, whose talent had just been demonstrated in Red River (1948). Clift was still filming The Heiress (1949) when Wilder approached him to star. Clift read the first act of the script, which is all Brackett and Wilder had completed at the time, and the actor enthusiastically agreed to play the protagonist writer. Meanwhile, Wilder secured his other ideal castmember: By the time he sought Erich von Stroheim to play Max von Mayerling, the former filmmaker-turned-butler for once-great silent film star Norma Desmond, the once obsessive auteur of Greed (1924) had fallen from grace—he had not fallen so far as to become a butler like his character, but he had taken several B-movie actor roles. Among them were a few brilliant performances, such as his memorable appearance in Jean Renoir’s Grand Illusion (1937). Von Stroheim’s parts as an actor were often sad, self-parodying portrayals of men who were once great but had fallen on hard times. He was a natural choice for a role he later described as a “crazy motion-picture director”. Von Stroheim observed that Wilder, “Likes his actors true to type, does he not?”

Although Wilder had initially wanted Mary Pickford as Norma Desmond, director George Cuckor suggested Gloria Swanson one afternoon when he and Wilder were having tea. Wilder immediately saw Swanson as the perfect choice. After all, her career had begun to fade after the troubled production of Queen Kelly (1929). That film, directed by none other than Erich von Stroheim, had been produced by Swanson and financed by Joseph Kennedy (father of John and Bobby), but von Stroheim’s “relentless perfectionism” enraged Swanson on the set. She complained to Kennedy, who in turn had von Stroheim fired, leaving the production to be finished by the studio, United Artists. Queen Kelly flopped and Swanson never regained her former stature. As a result of her situation, she agreed to appear as Norma Desmond before ever reading the script. At the time, she was earning a paltry $350 a week as a radio show performer in New York City. Her offer from Paramount Pictures, the studio she helped build in the 1920s, was for $50,000 over a 12-week shoot. Swanson jumped at the offer without questioning her role. “You must remember,” Wilder once remarked, “this was a star who at one time was carried in a sedan chair from her dressing room to the soundstage… She’d been one of the all-time stars, but when she returned to the screen in Sunset she worked like a dog.”

With their female lead cast, Wilder and Brackett began scouting locations for Norma Desmond’s “mausoleum”—a Hollywood mansion at 10086 Sunset Boulevard. The real location was 3810 Wilshire Boulevard, a house once owned by billionaire oil industrialist John Paul Getty and awarded to his ex-wife in a divorce settlement. The mansion, its façade designed to resemble a pseudo-Renaissance style, was not being lived in at the moment. Paramount rented the house for the shoot and installed the pool, in part for the film, in part as payment to the former Mrs. Getty for use of the mansion. In the film, one of the first shots is Joe floating dead in the pool, and he provides Sunset Boulevard’s framing device with his narration from the afterlife. He describes the house as “the kind of place that crazy movie people built in the crazy twenties.” The Getty house was used primarily for exteriors, while art director Hans Dreier and production designer John Meehan built sets in the studio—large, beautifully ornate sets with stained glass windows, velvet drapes, and other ornamentation that gave Norma’s home a museum-like quality. Or that of a crypt. Certainly, Norma feeds from Joe like a vampire, as if his presence nourishes her life-force; she always lingers behind him as he works on her Salome script and seems reenergized by his very presence.

With their female lead cast, Wilder and Brackett began scouting locations for Norma Desmond’s “mausoleum”—a Hollywood mansion at 10086 Sunset Boulevard. The real location was 3810 Wilshire Boulevard, a house once owned by billionaire oil industrialist John Paul Getty and awarded to his ex-wife in a divorce settlement. The mansion, its façade designed to resemble a pseudo-Renaissance style, was not being lived in at the moment. Paramount rented the house for the shoot and installed the pool, in part for the film, in part as payment to the former Mrs. Getty for use of the mansion. In the film, one of the first shots is Joe floating dead in the pool, and he provides Sunset Boulevard’s framing device with his narration from the afterlife. He describes the house as “the kind of place that crazy movie people built in the crazy twenties.” The Getty house was used primarily for exteriors, while art director Hans Dreier and production designer John Meehan built sets in the studio—large, beautifully ornate sets with stained glass windows, velvet drapes, and other ornamentation that gave Norma’s home a museum-like quality. Or that of a crypt. Certainly, Norma feeds from Joe like a vampire, as if his presence nourishes her life-force; she always lingers behind him as he works on her Salome script and seems reenergized by his very presence.

As the writing continued, it became clear Marshman and Wilder were doing most of the writing. Brackett, whose long relationship with Wilder had begun to disintegrate, received onscreen credit for his participation, but Paramount paid him only as a producer; payouts for writing went to Wilder and Marshman alone. Brackett was more useful helping Wilder secure cameos for the film’s many real-life Hollywood types: gossip columnists Hedda Hopper and Sidney Skolsky appeared as themselves, as well as epic director Cecil B. DeMille. But just as the story was forming and filming was ready to commence, Clift bowed out of the role, worried that he could not be convincingly in love with an older woman. Wilder called his reasoning “bullshit” and argued that if Clift was any kind of actor, he would be convincing “making love to any woman.” Wilder went on to recast the role. Moreover, Brackett learned that Clift had been in the midst of an affair with former Broadway starlet Libby Holman, who was fifteen years older than the actor. Holman, who was accused of shooting her husband Zachary Reynolds in 1932 (it was later determined he committed suicide), believed the plot of Sunset Boulevard was loosely based on her life. She supposedly threatened to kill herself if Clift took the role, so the actor turned it down. Wilder began looking elsewhere for his leading man.

William Holden had received much acclaim for his performance in Golden Boy (1939), but had not yet lived up to his promise and spent the last decade in forgettable studio projects. A good-looking guy with a helluva smile and the promise of mischief behind it, Holden was unknown enough that his off-screen—or even onscreen—persona would not impede his character’s nobody status. He was a relative unknown, despite more than a decade of Hollywood acting to his credit. He had also earned a reputation as a hard drinker and his career was on a downslide. In other words, he was perfect for Joe Gillis. But like Paul Newman, Holden had an instant charisma and knowable onscreen presence; he excelled at characters who were charming in their cynicism, as demonstrated in later films like Stalag 17 (1953) and The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957). He leaped at the role of Joe Gillis, but just before shooting began, Holden admitted to Wilder he was worried about getting into character. Who was this Joe Gillis anyway? “Do you know Bill Holden?” Wilder asked his lead actor. Of course he did. “Then you know Joe Gillis.” Holden was more like Joe Gillis than Wilder knew. The actor later admitted to being “a whore” like Joe Gillis. “When I was a young actor starting out in Hollywood, I used to service actresses who were older than me.” Nevertheless, Holden’s character serves as our entry point into the disturbing yet entertaining world of forgotten silent film star Norma Desmond.

Shooting began on April 18, 1949, and from the first scene, filming was a technical challenge. The opening scene shows Joe’s corpse floating facedown in Norma’s swimming pool, around which police officers and reporters are looking down, while the shot itself looks up from the bottom—“From a fish’s viewpoint,” Wilder described. Meehan conceived a brilliant trick shot so Seitz could achieve the look his director wanted; he placed a large mirror at the bottom of the pool, and then Seitz pointed the camera at it. The reflection of the mirror captured the shot without the need to rent expensive underwater camera equipment. As filming continued, Brackett became increasingly concerned that Wilder was incorporating several ugly real-life parallels to both Swanson and von Stroheim; at least, more than Brackett had originally helped conceive. Brackett wanted a comedy with some dramatic undertones. What Wilder was filming was much different. During an argument over the extended montage where Norma undergoes no end of treatments to make herself look young again for a role, Brackett came to blows with the director over its vulgarity. Wilder argued that the sequence would demonstrate what in fact someone Swanson’s age would endure to appear Hollywood-ready. After the fight was broken up by a production assistant, Wilder vowed never to work with Brackett again. After the bulk of the principal photography was completed in the summer of 1949, the two men—who had worked together on Ninotchka (1939), Ball of Fire (1941), The Lost Weekend (1945), and A Foreign Affair (1948), among many others—announced their partnership had come to an end.

Just as he had given suggestions to Renoir on the set of Grand Illusion, von Stroheim gave Wilder ideas on Sunset Boulevard. And since the script was unfinished when filming began, Wilder was receptive to input. It was von Stroheim’s idea to reveal that Max was writing all of Norma’s fan letters; the former director even suggested a scene where Max washes Norma’s underwear and caresses them with fetishistic attention, but Wilder felt that was going too far. Wilder also admitted that, for the scene when Norma shows Joe one of her films, the film should be Queen Kelly, the disastrous picture on which von Stroheim was sacked and Swanson’s career was ruined. Filming wrapped on June 18, 1949, with reshoots commencing over the next few weeks. Months were spent editing the film together and applying Franz Waxman’s score, with a chilling sound worthy of Bernard Herrmann and elsewhere tango-inspired notes, emphasizing the scene where Norma remembers her tango with Rudolph Valentino (Swanson tangoed with Valentino in real life too, in the film Beyond the Rocks, from 1922). As late as November and December of that year, Wilder was still toying with reshoots to improve the tone of certain scenes. The film’s final shot, where Norma descends her staircase from a considerable distance and proclaims she’s ready for her close-up, required another nine takes before Wilder was satisfied with the tone, the crazed look in Swanson’s eyes, how her spidery hands offer dancelike gestures, and the way her appearance goes slightly out of focus before the shot fades.

In January of 1950, Sunset Boulevard was screened in Chicago with an alternate opening, where Joe Gillis, a corpse with a “homicide” toe tag, recounts his story to the other bodies in the morgue. That opening was so ill-received that Wilder resolved to cut it all together and begin with the shot of Joe in the pool, now considered one of the most iconic openings in cinematic history. The Hollywood preview came months later in April and was attended by the town’s most prestigious company. Many talents such as Mary Pickford and Barbara Stanwyck (who reportedly knelt down and kissed the hem of Swanson’s gown) praised the film, while Mayer blew up at Wilder in the lobby, as discussed above. Wilder later defended his film as not anti-Hollywood, since Betty tries to correct Joe’s behavior; moreover, the film never derides any specific pictures or people. Critics received the film with largely glowing reviews. The Hollywood Reporter wrote, “That this completely original work is so marvelously satisfying, dramatically perfect, and technically brilliant is no haphazard Hollywood miracle but the inevitable consequence of the collaboration of Charles Brackett and Billy Wilder.” Renowned critic James Agee wrote in Sight and Sound, “Sunset Boulevard is much the most ambitious movie about Hollywood ever done, and is the best of several good ones into the bargain.” The subsequent year, the film earned Oscar nominations for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor, Best Actress, Best Supporting Actor, and Best Supporting Actress (Nancy Olson), but won for only Best Screenplay, Best Score, and Best Art Direction. Many of the awards were lost to Joseph Mankiewicz’s All About Eve, a far less cynical behind-the-scenes drama about show business.Today, Sunset Boulevard is an essential component to any discussion of the best films ever made.

Much of Sunset Boulevard remains fascinating for how Wilder dares to imitate life with his art, yet always with a wry sense of morbid humor. When Desmond plays bridge with a threesome of fellow former stars Joe refers to as “the waxworks,” Wilder casts silent film comedian Buster Keaton; H.B. Warner, who played Jesus in DeMille’s King of Kings (1924); and Anna Q. Nilsson, the silent film star. Von Stroheim hated the idea of appearing in a film alongside DeMille, who was still making successful films despite being a less significant talent. As a result, von Stroheim was jealous and resentful toward the role; reportedly, he walked around the set mumbling to himself, “Why are they doing this to me?” Von Stroheim’s butler tells Joe, “There were three young directors who showed promise in those days: D.W. Griffith, Cecil B. De Mille, and Max von Mayerling.” Replace the name von Stroheim for von Mayerling and it would be a historically accurate statement. That Max was a former director who discovered young Norma, made her a star, and married her was not strange. This was a not uncommon practice among Hollywood talent of this era, most famously by Charles Chaplin. Even after their divorce, Max insists on becoming her servant just to be close to her—a detail that shows audiences just how desirable Norma was in her day. But this was also true of Swanson.

Much of Sunset Boulevard remains fascinating for how Wilder dares to imitate life with his art, yet always with a wry sense of morbid humor. When Desmond plays bridge with a threesome of fellow former stars Joe refers to as “the waxworks,” Wilder casts silent film comedian Buster Keaton; H.B. Warner, who played Jesus in DeMille’s King of Kings (1924); and Anna Q. Nilsson, the silent film star. Von Stroheim hated the idea of appearing in a film alongside DeMille, who was still making successful films despite being a less significant talent. As a result, von Stroheim was jealous and resentful toward the role; reportedly, he walked around the set mumbling to himself, “Why are they doing this to me?” Von Stroheim’s butler tells Joe, “There were three young directors who showed promise in those days: D.W. Griffith, Cecil B. De Mille, and Max von Mayerling.” Replace the name von Stroheim for von Mayerling and it would be a historically accurate statement. That Max was a former director who discovered young Norma, made her a star, and married her was not strange. This was a not uncommon practice among Hollywood talent of this era, most famously by Charles Chaplin. Even after their divorce, Max insists on becoming her servant just to be close to her—a detail that shows audiences just how desirable Norma was in her day. But this was also true of Swanson.

Wilder wants to show his audience that Hollywood does not consist of only glitz and glam; rather, he reveals the sordid underbelly. Consider the opening shot where the title appears on the curbside, virtually in the sewer instead of a high and noble street sign—shown later in the film when the police come rushing to Norma’s mansion to cover Joe’s murder. Likewise, Norma’s name was derived from Mabel Normand, a silent comedienne who bedded William Desmond Taylor, an early silent film director with over fifty credits. Taylor was murdered in 1922. Normand was implicated but never convicted of Taylor’s unsolved murder and the scandal ruined her career. Wilder and his fellow screenwriters may have drawn from true Hollywood lore, but their uses for such parallels were not to create a monster, even if Norma has monstrous qualities. Joe’s time in Norma’s mansion may be strange, like living with a Hollywood version of Miss Havisham from Great Expectations, as Joe later suggests, but it’s never dull. She puts on old films and performs funny routines. Swanson is particularly great in a sequence where she impersonates Charlie Chaplin—which she had done before in Manhandled (1924). She had also starred alongside Chaplin in his early short for Essnay Studios, His New Job (1915). For each of Sunset Boulevard‘s strangest moments, there’s a real-life counterpart warped for the purposes of the film, some of them horrifying, some of them endearing.

But Swanson was not her character—not a crazed former starlet now driven mad by the abandonment of her fans; she was a hard-working actress who wasn’t above keeping busy in summer stock productions and radio shows to keep up appearances. However, she was not immune to her ego. When Paramount demanded a screen test of Swanson, she replied, “Without me, there would be no Paramount Pictures”—a line that would be said by Norma as well. When she arrived back at the Paramount lot, she was greeted with a warm welcome. “Right back in the jungle,” she told the media. “Up to my ears in the rat race.” Swanson was playing a character who, like her, “had been given the brush by thirty million fans.” Von Stroheim’s Max describes her best: “She was the greatest of them all. You wouldn’t know; you’re too young. In one week she received seventeen thousand fan letters. Men bribed her hairdresser to get a lock of her hair. There was a maharaja who came all the way from India to beg for one of her silk stockings. Later he strangled himself with it.” And in the role, Swanson’s performance is incredible. Her entire posture seems to be ever ready for the camera, with her head tilted back and her eyes almost pulled open by her arching eyebrows. Her fingers bend in clawlike contortions and, combined with the spidery stance, she creates a vampiric pose in some scenes, recalling Max Schreck in F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922).

Throughout Sunset Boulevard, Wilder demonstrated what he believes is the truth about Hollywood. Screenwriters, in particular, see a symbiotic relationship between themselves and actors, directors, or producers; however, as Joe Gillis discovers, the relationship proves parasitic and even cannibalistic. That relationship is the true nature of Hollywood. Before anyone else was willing to remark on their own industry with such scathing representation of Hollywood’s grotesque underworld, Sunset Boulevard lays bare Tinseltown’s flashy allure, making way for Hollywood satires from The Bad and the Beautiful (1952) to The Player (1992) to Mulholland Dr. (2001). But Wilder’s film contains line after line of memorable dialogue, scene after scene of iconic shots, and an ensemble of disturbingly reflective performances from its humbled cast. Wilder carefully uses Holden’s greenness, as well as Desmond and von Stroheim’s desperation to create something truly uncommon, fascinating, and brilliant. An inspired depiction of how Hollywood is a series of extravagant delusions, and a tale that demystifies the glamour and allure of fame, Wilder’s film warps all notions of Hollywood’s Golden Age and turns them into an unsettling nightmare.

Bibliography:

Hopp, Glen. Billy Wilder: The Complete Films, The Cinema of Wit. Taschen, 2003.

Horton, Robert (editor). Billy Wilder: Interviews. Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2001.

McNally, Karen (editor). Billy Wilder, Movie-Maker: Critical Essays on the Films. McFarland, 2010.

Phillips, Gene D. Some Like It Wilder: The Life and Controversial Films of Billy Wilder. University Press of Kentucky, 2009.

Sikov, Ed. On Sunset Boulevard: The Life and Times of Billy Wilder. New York: Hyperion, 1998.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review