The Definitives

Sullivan’s Travels (1941)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Preston Sturges’ Sullivan’s Travels begins with the finale of another motion picture, a film within the film. On the screen, a young vagabond and a railway yard boss wrestle atop a speeding train. When the yard boss pulls a revolver and fires a few rounds, the vagabond leaps at him. As the train passes over a river bridge, the two men struggle their way over the side and fall to their deaths into the water, over which appears “THE END”. Watching with enthusiasm in a dark screening room, director John L. Sullivan sees the picture as essential, important filmmaking that defines the nation’s then-current financial and political turmoil. He’s using the film to convince his studio bosses to allow him to launch a production of O Brother, Where Art Though? Sullivan proclaims, “You see the symbolism of it! Capital and labor destroy each other! It teaches a lesson, a moral lesson, that has social significance.” Sullivan wants to incorporate such message-making in his next project. The two studio executives watching along with him could not be more disinterested in its commentaries; they just want something that sells, and what sells better than sex? Meanwhile, Sullivan announces his aspirations: “I want this picture to be a commentary on modern conditions—stark realism, the problems that confront the average man.” An exec responds, “But with a little sex in it.” Sullivan replies, “A little, but I don’t want to stress it. I want this picture to be a document. I want to hold a mirror up to life. I want this to be a picture of dignity—a true canvas of the suffering of humanity.” The exec replies, “But with a little sex in it.” And Sullivan concedes, “But with a little sex in it.”

Although this opening scene crackles with Sturges’ signature wit and rapid-fire comic timing, beneath it resides the pairing of humor and commentary that makes Sullivan’s Travels the director’s finest film. Amid physical gags, Hollywood satire, and bustlingly funny dialogue, Sullivan’s Travels from 1941 substantiates the entire body of work by its writer-director, by declaring that escapism, such as diversionary laughs, are the vanguard of important cinema. More to the point, Sturges had grown frustrated by soapboxing directors. In response, he set out to stress the importance of cinema as an artist’s escapist device, wherefrom the true application of artistry was hiding a commentary within the escape. Sturges explained, “I read that it was the playwright’s job to show conditions but to let the audience draw conclusions.” He said the film was “the result of an urge, an urge to tell some of my fellow filmwrights that they were getting a little too deep-dish and to leave the preaching to the preachers… Sullivan’s Travels could really have been a little pamphlet sent around privately.” What Sturges offers, ironically, is a message film telling us the world no longer needs message films; and yet, the commercial and financial success of Sullivan’s Travels proves the potential of relevant commentary embedded into entertainment. Sturges would later admit his folly, writing in autobiography, “It made some horrible crimes against juxtaposition, as a result of which I took a few on the chin.” He continued, “One local reviewer wanted to know what the hell the tragic passages were doing in this comedy, and another wanted to know what the comic passages were doing in this drama.” But this was Sturges’ genius: to combine uncultured humor with high-brow ideologies, balancing the sophisticated with the unpolished needs of the masses.

Sturges’ upbringing reflected his work: at once worldly and earthy (in their antithetical meanings). Born in 1898, Sturges grew up under the wing of his bohemian-cosmopolitan mother, Mary Estelle Dempsey, who took her child to Paris at the age of three. Uninterested in exploring the world, he had culture thrust upon him. As he grew, he despised yet could not escape his mother’s influence and spent much time traveling between Europe and the United States. In New York City at the Desti Emporium, the store owned by his mother’s fourth husband, Sturges invented a type of non-stick lipstick in their lab. He was known to be always tinkering with some new gizmo, as well as quickly growing disinterested toward whatever that project may be. He invented a tickertape machine and an intaglio photo-etching process; he designed a type of automobile and an airplane too. Genius notwithstanding, his attention would waver, even when writing—the talent upon which he would ultimately settle. With his nose constantly in his favorite book, How Never to Be Tired: Two Lifetimes in One, he would rarely sleep, and always shift modes, activating on one thing and then the next in an ever-going surge of productivity. Sturges began producing his own stage plays for Broadway in 1929. After his hit The Guinea Pig, he struck gold with Strictly Dishonorable, a piece written in six days that would earn him $300,000. After a few more years on Broadway, Hollywood came calling. His first screenplay was for Fox, called The Power and the Glory (1933), the vehicle that drove Spencer Tracey to stardom. Sturges was paid $17,500, plus a chunk of the film’s profits; due to its success, his cut became a hefty sum. The rewarding arrangement was then unheard of, giving Sturges the kind of payday and attention usually reserved for directors and their stars.

Sturges’ upbringing reflected his work: at once worldly and earthy (in their antithetical meanings). Born in 1898, Sturges grew up under the wing of his bohemian-cosmopolitan mother, Mary Estelle Dempsey, who took her child to Paris at the age of three. Uninterested in exploring the world, he had culture thrust upon him. As he grew, he despised yet could not escape his mother’s influence and spent much time traveling between Europe and the United States. In New York City at the Desti Emporium, the store owned by his mother’s fourth husband, Sturges invented a type of non-stick lipstick in their lab. He was known to be always tinkering with some new gizmo, as well as quickly growing disinterested toward whatever that project may be. He invented a tickertape machine and an intaglio photo-etching process; he designed a type of automobile and an airplane too. Genius notwithstanding, his attention would waver, even when writing—the talent upon which he would ultimately settle. With his nose constantly in his favorite book, How Never to Be Tired: Two Lifetimes in One, he would rarely sleep, and always shift modes, activating on one thing and then the next in an ever-going surge of productivity. Sturges began producing his own stage plays for Broadway in 1929. After his hit The Guinea Pig, he struck gold with Strictly Dishonorable, a piece written in six days that would earn him $300,000. After a few more years on Broadway, Hollywood came calling. His first screenplay was for Fox, called The Power and the Glory (1933), the vehicle that drove Spencer Tracey to stardom. Sturges was paid $17,500, plus a chunk of the film’s profits; due to its success, his cut became a hefty sum. The rewarding arrangement was then unheard of, giving Sturges the kind of payday and attention usually reserved for directors and their stars.

Somewhat ostracized by his fellow writers, who often worked in packs and were paid with scraps, Sturges pioneered Hollywood like no other writer had at the time. After cranking out a series of screenplays for popular films—including Diamond Jim (1935), Easy Living (1937), and Remember the Night (1940)—he became frustrated with his position as merely a writer. Few directors seemed to understand the flow of his dialogue, how every line had an intended inflection and speed of delivery. Yearning for total control, he made a deal with Bill LeBaron at Paramount Pictures in 1940. He sold his script for The Great McGinty, which he had completed six years prior, for $1 with the understanding that he would be allowed to direct, thus having creative rein over the story and dialogue of his picture. In 1940, it was unprecedented for a screenwriter to bring his or her own vision to the screen. Today the writer-director phenomenon is common, but only because Preston Sturges proved it possible.The writer-director trend was followed by John Huston, Orson Welles, and Billy Wilder, but it may not have been had The Great McGinty not performed so well, eventually earning Sturges the Academy Award for Best Writing of an Original Screenplay. The film’s immediate box-office success convinced Paramount to allow Sturges another directorial job with Christmas in July, also released in 1940. By this time, Hollywood was abuzz with talk of Preston Sturges, the “boy wonder” (though he was in his early forties) who delivered two hits in a single year. With The Lady Eve in 1941, Sturges released his most universally praised and highest grossing film to date, all while maintaining an extraordinary degree of independence on his productions. After his trio of box-office success, he had no trouble at all convincing Paramount to produce his next picture, which attacked Hollywood’s creative inbreeding through comedy, satire, social commentary, and reflective industry mirror all at once.

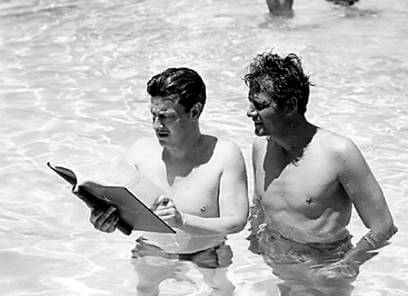

Sturges wrote Sullivan’s Travels with his leading man already in mind. Sturges wanted only Joel McCrea, an actor whose sincerity and presence can and had been molded. McCrea was a blank template with genial charm that could be placed into any role. Though he was best known for Westerns, directors like Alfred Hitchcock and Sturges would recurrently exploit his everyman uniformity. McCrea and Sturges met years before on the Fox lot, while the actor visited his friend Spencer Tracy on the set of The Power and the Glory. About three years later, McCrea bumped into McCrea again on the Paramount lot. They had been loosely acquainted over the years, but not enough that McCrea believed Sturges when he said, “I’ve written a script for you.” McCrea, believing Sturges was blowing Hollywood smoke, replied, “No one writes a script for me, they write a script for Gary Cooper and if they can’t get him, they use me.” Nevertheless, Sturges invited the actor back to his office and showed McCrea the script for Sullivan’s Travels. McCrea jumped at the part, not because it stretched his acting muscles or would earn him an award, but because it was an important role, a character whose presence had been defined by what was on the printed page. He once said, “Most of the other male stars bring a certain thing; Cagney, for instance, would always be Cagney. But this was John L. Sullivan—he couldn’t be a movie star. He could be Sturges, he could be me.” Sturges also knew he wanted Veronica Lake as his leading lady, despite warnings that the up-and-coming actress with the peek-a-boo hairstyle was reportedly difficult to work with. He cast her against type in a comic role, whereas Lake had already been typecast as a vamp of sorts. The studio heads were against both of Sturges’ leads for the film, but given the director’s streak of box-office winners, they could hardly question his judgment. Along with the director’s own troupe of onscreen regulars—including William Demarest, Jimmy Conlin, Byron Foulger, Robert Grieg, Charles R. Moore, Franklin Pangborn, and Robert Warwick—McCrea and Lake offer two of the most amiable performances found in a Sturges picture.

Sturges wrote Sullivan’s Travels with his leading man already in mind. Sturges wanted only Joel McCrea, an actor whose sincerity and presence can and had been molded. McCrea was a blank template with genial charm that could be placed into any role. Though he was best known for Westerns, directors like Alfred Hitchcock and Sturges would recurrently exploit his everyman uniformity. McCrea and Sturges met years before on the Fox lot, while the actor visited his friend Spencer Tracy on the set of The Power and the Glory. About three years later, McCrea bumped into McCrea again on the Paramount lot. They had been loosely acquainted over the years, but not enough that McCrea believed Sturges when he said, “I’ve written a script for you.” McCrea, believing Sturges was blowing Hollywood smoke, replied, “No one writes a script for me, they write a script for Gary Cooper and if they can’t get him, they use me.” Nevertheless, Sturges invited the actor back to his office and showed McCrea the script for Sullivan’s Travels. McCrea jumped at the part, not because it stretched his acting muscles or would earn him an award, but because it was an important role, a character whose presence had been defined by what was on the printed page. He once said, “Most of the other male stars bring a certain thing; Cagney, for instance, would always be Cagney. But this was John L. Sullivan—he couldn’t be a movie star. He could be Sturges, he could be me.” Sturges also knew he wanted Veronica Lake as his leading lady, despite warnings that the up-and-coming actress with the peek-a-boo hairstyle was reportedly difficult to work with. He cast her against type in a comic role, whereas Lake had already been typecast as a vamp of sorts. The studio heads were against both of Sturges’ leads for the film, but given the director’s streak of box-office winners, they could hardly question his judgment. Along with the director’s own troupe of onscreen regulars—including William Demarest, Jimmy Conlin, Byron Foulger, Robert Grieg, Charles R. Moore, Franklin Pangborn, and Robert Warwick—McCrea and Lake offer two of the most amiable performances found in a Sturges picture.

With a budget of around $600,000 and a shooting schedule of 45 days, Sullivan’s Travels began filming on May 7, 1941. Of his director, McCrea remarked he was “intelligently conceited”. Sturges was known as a “wunderkind” thanks to the Paramount publicity department, but the label was far from exaggeration. “He knew he was great,” said McCrea. “He knew what he was doing was good. He didn’t question what he was doing was going to get great review from the very first day he started shooting.” McCrea could not speak so confidently of Lake, who required a dozen or more takes to get a scene because she did not know her lines. And by the time she began to get her lines correct, she had become exhausted and needed a rest. Perhaps her behavior could be explained by the secret Lake had been keeping: she was six-months pregnant when shooting began—something she avoided telling Sturges until cameras were rolling. “I knew I had to do something and do it quickly,” Lake remembered in her autobiography. “But I couldn’t get up the guts to simply tell him.” She resolved to confide in Sturges’ wife, Louise, who was also pregnant at the time. “Don’t tell Preston, but I’m pregnant,” she whispered to Louise. Sturges’ wife replied, “I certainly will not tell him, but I’ll give you a two-minute running start to tell him yourself.” When he found out, Sturges had to restrain his frustration. Legendary costume designer Edith Head did her best to cover up Lake’s budding tummy, but the pregnancy is visible at times in the finished film. In all, Lake delayed Sturges’ usual four pages of shooting a day by half.

Regardless, Sturges had impressed the studio heads with a daring feat early into the production, and it was enough to diffuse any future studio pressure on the production before it started. While setting up to shoot the complicated opening sequence where Sullivan’s preaches about filmic morality to his producers, cameraman John F. Seitz proposed that they shoot the entire scene in a single take. In fact, Seitz dared the director to do it: “I dare you to take it all in one.” Sturges liked Seitz; both men were inventors and tinkerers. He accepted it as a personal challenge. McCrea was nervous about filming the sequence—this was not the way his usual programmers were shot. Traditionally, a Hollywood production used shorter takes, requiring just a few lines before the director called “Cut!” McCrea agreed to try, and they completed the two days of work in little more than an hour. The scene consisted of ten screenplay pages and four-and-a-half minutes of screentime. Immediately, Sturges announced their accomplishment and the studio buzzed about what they had done. Cecil B. DeMille was not impressed. He told McCrea, “Well, you work with these geniuses, these talented men, but my pictures make more money than theirs do.” McCrea replied, “But C.B., you don’t give me a percentage of them. I don’t get any more working for you than I do working for those geniuses.” To be sure, Sturges made McCrea feel like an A-list movie star on the set, enough so that later McCrea said he would work with Sturges for free.

Regardless, Sturges had impressed the studio heads with a daring feat early into the production, and it was enough to diffuse any future studio pressure on the production before it started. While setting up to shoot the complicated opening sequence where Sullivan’s preaches about filmic morality to his producers, cameraman John F. Seitz proposed that they shoot the entire scene in a single take. In fact, Seitz dared the director to do it: “I dare you to take it all in one.” Sturges liked Seitz; both men were inventors and tinkerers. He accepted it as a personal challenge. McCrea was nervous about filming the sequence—this was not the way his usual programmers were shot. Traditionally, a Hollywood production used shorter takes, requiring just a few lines before the director called “Cut!” McCrea agreed to try, and they completed the two days of work in little more than an hour. The scene consisted of ten screenplay pages and four-and-a-half minutes of screentime. Immediately, Sturges announced their accomplishment and the studio buzzed about what they had done. Cecil B. DeMille was not impressed. He told McCrea, “Well, you work with these geniuses, these talented men, but my pictures make more money than theirs do.” McCrea replied, “But C.B., you don’t give me a percentage of them. I don’t get any more working for you than I do working for those geniuses.” To be sure, Sturges made McCrea feel like an A-list movie star on the set, enough so that later McCrea said he would work with Sturges for free.

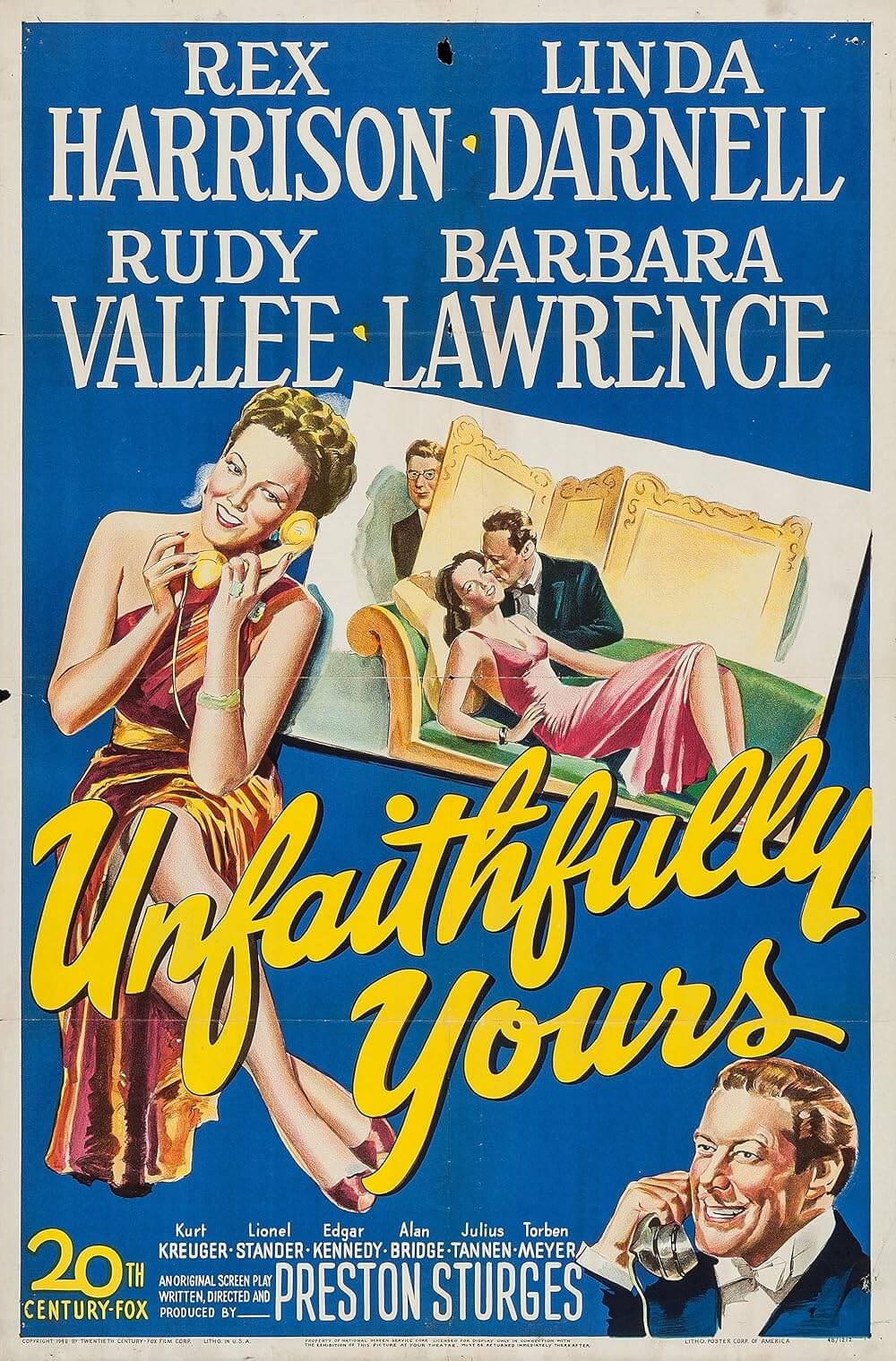

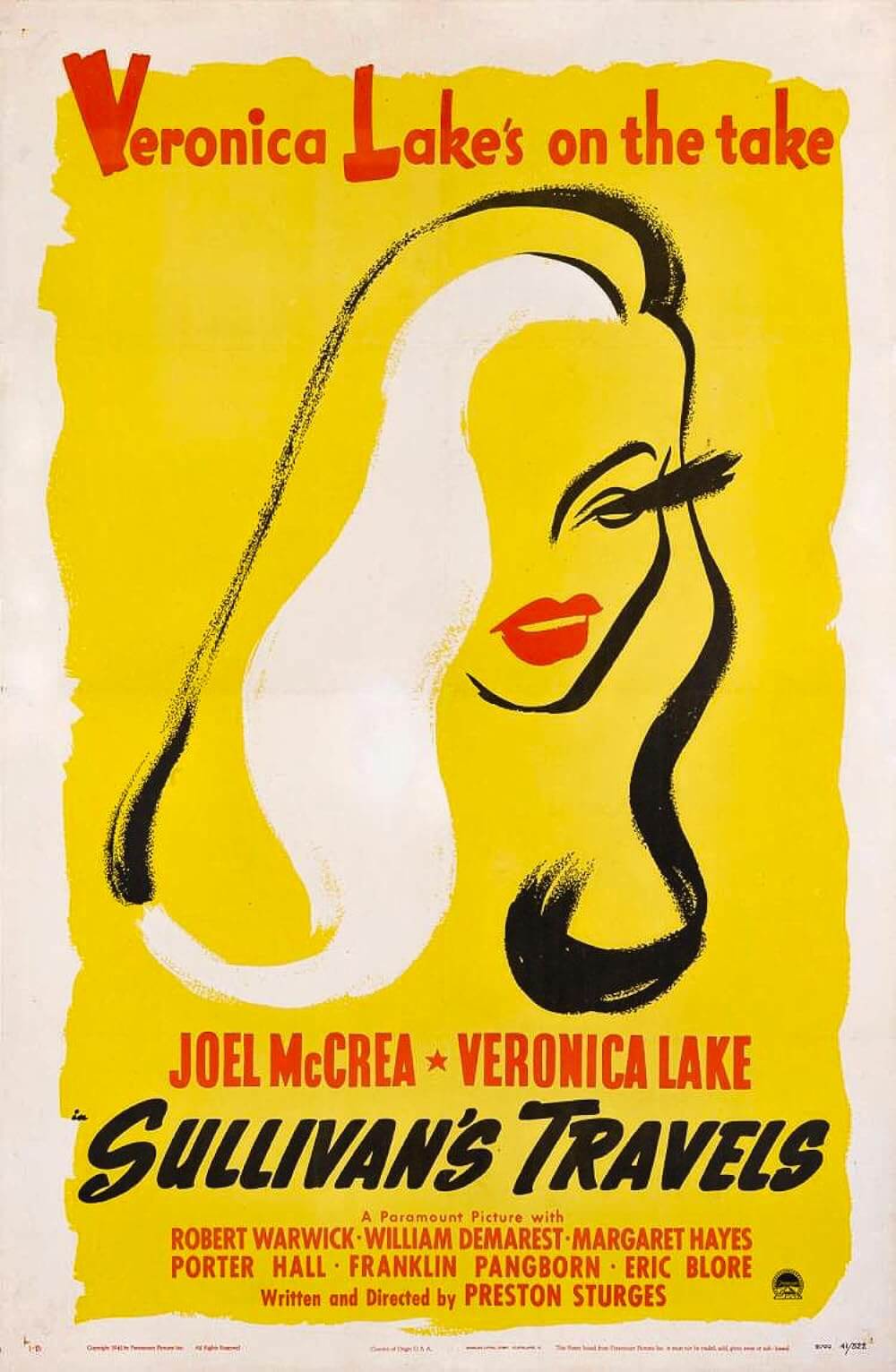

Shooting wrapped in July 1941, just nine days past the scheduled end and $76,000 over budget. Though Lake had only a supporting role next to McCrea, the marketing campaign relied on Lake’s face on the poster to sell the film. The posters read the tagline “Veronica Lake’s on the take” but the message was clear—Sturges had all too accurately represented the struggle between the artist-director and his studio heads, who seemed determined to sell a picture “with a little sex in it.” Sullivan’s Travels was released just one week after Sturges concluded filming his next film, The Palm Beach Story, which also starred McCrea. It performed well-enough to keep Sturges’ reputation for delivering a profit intact, but not as well as his previous films. By sending up his preachy contemporaries and their haughty, socially significant films, he made such a film itself. Sturges may not be as pontifical as John L. Sullivan intends to be, but his film is not wholly escapist either. There is a social message by proxy. Nevertheless, Sturges maintains his comic edge by following his eleven rules for box-office success:

1. A pretty girl is better than an ugly one.

2. A leg is better than an arm.

3. A bedroom is better than a living room.

4. An arrival is better than a departure.

5. A birth is better than a death.

6. A chase is better than a chat.

7. A dog is better than a landscape.

8. A kitten is better than a dog.

9. A baby is better than a kitten.

10. A kiss is better than a baby.

11. A pratfall is better than anything.

Sullivan’s Travels opens in an America where WWII rages overseas and an economic recession places most of the country into a state of poverty. In response, John L. Sullivan has reserved his next movie for the poor masses, calling it O Brother, Where Art Thou? (In 2000, Joel and Ethan Coen borrowed this faux title for their own so-named starring George Clooney, which also focused on ragtag folk: escaped members of a chain gain. The writing-directing-producing siblings habitually, and effectively, borrow from Sturges.). Sullivan’s picture was an adaptation of a fictional novel by fictional author “Sinclair Beckstein”, Sturges’ amalgamation of Upton Sinclair and John Steinbeck. He intends to deliver a cinematic ode to the hardships of Middle America. But what does a Hollywood director, born with a silver spoon in his mouth, know about hardship? Nothing, he resolves. And so, Sullivan heads into the wild disguised as a hobo, hoping to experience enough misery to authenticate his proposed American Tragedy. Trying desperately to assimilate into the great unwashed, Sullivan distances himself from studio overseers and his own entourage. He sets out onto the road and plans to hitchhike his way across the U.S., only he inadvertently hitches his way back (wouldn’t you know it) to Hollywood. Disenchanted by his failed absorption into disenchantment, Sullivan resigns to breakfast. In a small diner, Sullivan meets a kind young woman played by Lake, a would-be actress giving up her trade and heading home. Credited only as The Girl, Lake’s character buys the seemingly desperate bum a plate of ham and eggs. Sullivan rewards her kindness, revealing his high-profile identity and the reasons behind his incognito expedition. Smitten, the two set out together, into America’s heartland, for a taste of poverty.

Sullivan’s Travels opens in an America where WWII rages overseas and an economic recession places most of the country into a state of poverty. In response, John L. Sullivan has reserved his next movie for the poor masses, calling it O Brother, Where Art Thou? (In 2000, Joel and Ethan Coen borrowed this faux title for their own so-named starring George Clooney, which also focused on ragtag folk: escaped members of a chain gain. The writing-directing-producing siblings habitually, and effectively, borrow from Sturges.). Sullivan’s picture was an adaptation of a fictional novel by fictional author “Sinclair Beckstein”, Sturges’ amalgamation of Upton Sinclair and John Steinbeck. He intends to deliver a cinematic ode to the hardships of Middle America. But what does a Hollywood director, born with a silver spoon in his mouth, know about hardship? Nothing, he resolves. And so, Sullivan heads into the wild disguised as a hobo, hoping to experience enough misery to authenticate his proposed American Tragedy. Trying desperately to assimilate into the great unwashed, Sullivan distances himself from studio overseers and his own entourage. He sets out onto the road and plans to hitchhike his way across the U.S., only he inadvertently hitches his way back (wouldn’t you know it) to Hollywood. Disenchanted by his failed absorption into disenchantment, Sullivan resigns to breakfast. In a small diner, Sullivan meets a kind young woman played by Lake, a would-be actress giving up her trade and heading home. Credited only as The Girl, Lake’s character buys the seemingly desperate bum a plate of ham and eggs. Sullivan rewards her kindness, revealing his high-profile identity and the reasons behind his incognito expedition. Smitten, the two set out together, into America’s heartland, for a taste of poverty.

Seven-minutes of unvoiced mosaic follow Sullivan and his blonde bombshell companion (disguised as a boy) as they tour the lower depths. We hear nothing but heartening music play over their journey of eating in missions and sleeping on floors. The change in Sturges’ tone is sudden, but poignant, in that the stark absence of his staccato dialogue leaves the viewer an empty sponge, soaking up the sobering imagery. Their self-inflicted squalor continues until she gives him a pained look, having whiffed the entrails of a trash can—the source of their next meal. Back to Hollywood, his lesson learned, Sullivan renders his research for O Brother, Where Art Thou? complete. After cleaning up, he grabs a stack of five-dollar bills, gets back into his tramp garb for one last night, and distributes what he can to needy unfortunates. But Sullivan is followed by a sneaky vagrant who knocks the director about the head and robs him of his loot. Soon enough, Sullivan finds himself on a train to who-knows-where. While the thief certainly receives his comeuppance, our hero awakes in a train yard, disoriented with temporary amnesia. Before long, he finds himself shackled in a chain gang. But when he finally recalls his identity and tries to inform the prison guards it was all a mistake, they simply ignore his pleas. Now Sullivan truly understands social injustice, how his contemporary prisons are filled with good men who became desperate, and further, he learns true suffering in the confines of prison. One night, his prison crew attends a picture show at a local church. Mickey Mouse and Pluto run rampant on the screen, allowing Sullivan to see how a simple laugh benefits prisoners and churchgoers, the commoners he so sought to understand—a group to which he now belongs. Quick thinking places Sullivan back in Hollywood, again, where he resolves O Brother, Where Art Thou? can never be. He sees now that some small measure of escape, specifically a diversionary laugh, brings more hope and joy to the world than any message picture ever could.

Sturges remarked on the themes of Sullivan’s Travels: “When I started writing it I had no idea what Sullivan was going to discover. Bit by bit I took everything away from him—health, fortune, name, pride, and liberty. When I got down to there I found he still had one thing left: the ability to laugh.” When everything else is stripped away, laughter becomes essential; and since most of Sturges’ audience belongs to a category devoid of the good fortunes that Sullivan takes for granted, the message of Sullivan’s Travels becomes hugely significant. Sturges did not intend to justify the importance of comedies alone, however; he maintained that art is essential at all times, regardless of genre. How one goes about it—preachiness—is what Sturges meant to critique. Sturges wrote that cinema “helps to make up for the emotional deficiency in most people’s lives and as such is vastly useful.” To demonstrate this, he configures film commentary (as opposed to social commentary) into his picture, reminding fellow filmmakers that cinema’s greatest gift is sometimes, simply, an escape from the horrors of everyday life. His film supports the notion that escape is a connective tissue of the masses, but he communicates this lesson by, to a degree, breaking his own rule and teaching a crucial lesson. Regardless, it’s a lesson well-learned. Save for Sullivan’s Travels, Sturges’ pictures avoid political or social relevance, but rather carry a theme or thesis to their comedy. A Preston Sturges comedy is often more about an idea than a plot. Take his 1942 picture The Palm Beach Story, which proposes that beautiful women will always get a free ride. Just as that film uses the story and character to prove its contention, Sullivan’s Travels seeks to justify the cinema as an important tool Hollywood’s artists should use to provide a much-needed diversion.

Sturges remarked on the themes of Sullivan’s Travels: “When I started writing it I had no idea what Sullivan was going to discover. Bit by bit I took everything away from him—health, fortune, name, pride, and liberty. When I got down to there I found he still had one thing left: the ability to laugh.” When everything else is stripped away, laughter becomes essential; and since most of Sturges’ audience belongs to a category devoid of the good fortunes that Sullivan takes for granted, the message of Sullivan’s Travels becomes hugely significant. Sturges did not intend to justify the importance of comedies alone, however; he maintained that art is essential at all times, regardless of genre. How one goes about it—preachiness—is what Sturges meant to critique. Sturges wrote that cinema “helps to make up for the emotional deficiency in most people’s lives and as such is vastly useful.” To demonstrate this, he configures film commentary (as opposed to social commentary) into his picture, reminding fellow filmmakers that cinema’s greatest gift is sometimes, simply, an escape from the horrors of everyday life. His film supports the notion that escape is a connective tissue of the masses, but he communicates this lesson by, to a degree, breaking his own rule and teaching a crucial lesson. Regardless, it’s a lesson well-learned. Save for Sullivan’s Travels, Sturges’ pictures avoid political or social relevance, but rather carry a theme or thesis to their comedy. A Preston Sturges comedy is often more about an idea than a plot. Take his 1942 picture The Palm Beach Story, which proposes that beautiful women will always get a free ride. Just as that film uses the story and character to prove its contention, Sullivan’s Travels seeks to justify the cinema as an important tool Hollywood’s artists should use to provide a much-needed diversion.

At the time of the film’s release, many believed Sturges wrote himself as John L. Sullivan in a stroke of autobiographical indulgence, except Sturges never made message pictures, save for Sullivan’s Travels. Critics at the time and film historians today have underlined how Sturges’ film contains a message, but the film’s lesson never completely derails the audience-friendly comedy. Sturges knows what an audience wants and needs, whereas the Sullivan seems to be just now learning what his audience wants. The message within Sullivan’s Travels was not the preachy, stark social commentary or Sturges’ serious-minded contemporaries; rather, it was a directive to other filmmakers whose hoity-toity idealisms had been sermonized to the populace. Indeed, the personality of the film derives from Sturges’ own half-aristocrat, half-peasant persona, thematically signifying the writer-director’s penchant for the intellectual and accessible. Sturges even pokes fun at his director-character’s own filmography—at first, Sullivan wants to distance himself from his earlier fluff like Hey, Hey in the Hay Loft and the Busby Berkeley-inspired Ants in Your Plants of 1939 and their transparent motives, which emphasizes the gap between Sturges and his fictional director. To critics who claimed Sturges meant to represent himself in Sullivan, the director wrote a piece in the New York Times on the film’s creation entitled “An Author in Spite of Himself”. Sturges wrote, “Was I Sullivan? …I am not Sullivan’ He is a younger man than I, and a better one—a composite of some of my friends who tried preaching from the screen… wasting their excellent talents in comstockery, demogogy, and plain dull preachment.” And though Sullivan’s Travels seemingly breaks Sturges’ own rule by preaching to his fellow directors, the nature and power of the message remains.

However overrated Sturges believed message films to be, Charles Chaplin already proved years before that social satire and escapist comedy could exist within a single film, specifically in Modern Times (1938) and The Great Dictator (1940). Sturges draws clear influence from Chaplin’s The Tramp character. It’s impossible to look at Sullivan in his hobo garb and not see Chaplin’s down-and-out wanderer. Although the latter of these two Chaplin social-comedies literally puts its director at the podium, both films made comedy into charming, often germane art. Look at Modern Times, Chaplin’s most cleverly disguised political film: it does not feel like cinematic soap-boxing as much as engaging mirror and assessment of then-modern regimes, social stations, technology, and industry. Chaplin attacks conveyor belt industrialization with social libertarianism, resolving that the wheels of industry in which The Tramp is literally caught bring about unemployment, drugs, strikes, and a severe loss of human individuality. But then, this is one of the funniest movies ever made, its commentary purveyed via Chaplin’s most recognizable visual gags. There’s a sequence when, through a series of misunderstandings, The Tramp goes from sweeping up manure in the street to leading Communist march. Or consider his desperate attempts at keeping pace with a never-ending conveyor of loose screws, the repetitive actions leaves him twitching with muscle memory. While Chaplin made several examples of comedic message pictures (others Monsieur Verdoux and A King in New York), like Sturges, his output more often exists as pure comedy.

However overrated Sturges believed message films to be, Charles Chaplin already proved years before that social satire and escapist comedy could exist within a single film, specifically in Modern Times (1938) and The Great Dictator (1940). Sturges draws clear influence from Chaplin’s The Tramp character. It’s impossible to look at Sullivan in his hobo garb and not see Chaplin’s down-and-out wanderer. Although the latter of these two Chaplin social-comedies literally puts its director at the podium, both films made comedy into charming, often germane art. Look at Modern Times, Chaplin’s most cleverly disguised political film: it does not feel like cinematic soap-boxing as much as engaging mirror and assessment of then-modern regimes, social stations, technology, and industry. Chaplin attacks conveyor belt industrialization with social libertarianism, resolving that the wheels of industry in which The Tramp is literally caught bring about unemployment, drugs, strikes, and a severe loss of human individuality. But then, this is one of the funniest movies ever made, its commentary purveyed via Chaplin’s most recognizable visual gags. There’s a sequence when, through a series of misunderstandings, The Tramp goes from sweeping up manure in the street to leading Communist march. Or consider his desperate attempts at keeping pace with a never-ending conveyor of loose screws, the repetitive actions leaves him twitching with muscle memory. While Chaplin made several examples of comedic message pictures (others Monsieur Verdoux and A King in New York), like Sturges, his output more often exists as pure comedy.

Elsewhere, Sturges wrote an in-film reference to his inspiration, director Ernst Lubitsch. When discussing the merits of socially significant films with Sullivan, the Girl asks, “Did you ever meet Lubitsch?” Indeed, Lubitsch spoke to Sturges on a regular basis, which is evident when comparing their shared modus operandi. Hollywood’s most exalted director of romantic comedies, Lubitsch worked primarily from the Silent Era and on into the 1940s, becoming an idol to filmmakers like Sturges and Billy Wilder. Lubitsch left Germany for Hollywood in the ‘20s, where he single-handedly designed the American musical with his onscreen counterpart and ever-lovable charmer, actor Maurice Chevalier. Often considered the progenitor of romantic comedies, Lubitsch’s elegant films bear the delightful sophistication Sturges borrows from, if not surpasses. Both Sturges and Lubitsch reveled in challenging their contemporary Production Code restrictions, be it thematically, through clever wordsmithing, or with subtle imagery shrewdly maneuvered to outwit the review board’s moral policing. Consider how Lubitsch’s Trouble in Paradise was banned in 1936 for its suggestive themes: sympathy for the film’s two thief-lovers, adultery, criminality, and palpable sexuality are all apologized for within the delightfully romantic picture. Sturges likewise battled censors on his film The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek in 1944, wherein Betty Hutton finds herself married and knocked up after a night of boozing. If only she could remember to whom she was married.

Sturges dedicates his film in the opening titles, and surely the director counted Chaplin and Lubitsch among them: “To the memory of those who made us laugh: the motley mountebanks, the clowns, the buffoons, in all times and in all nations, whose efforts have lightened out burden a little, this picture is affectionately dedicated.” The dedication reads as if Sturges has not laughed for years, or that laughs in his era are few and far between. Though Sturges was writing about his preachy fellow directors, his remarks may seem more relevant today. Certainly, if Sturges were around today, he may have a similar sense of longing for a time of wit and satire amid today’s formulaic, homogenized, gross-out, and dim-witted comedies. Fortunately, film enthusiasts can readily access Sturges’ work in lieu of some contemporary trifle. Sturges, and Lubitsch before him, played with suggestions of sex, politics, and ideas generally believed to be unfunny—certainly not representational norms in the directors’ contemporary cinema. Forging such topics into wholly popularized subject matter through humor, they made way for their successors to further push boundaries. Theirs was a cinema wherein graceful metaphor married urbane salaciousness, together creating elegant masterworks of comic wisdom. Sullivan’s Travels remains an unconventional comedy, a blend of slapstick and drama, and one of the few effective message films in any genre. Sturges set out to make entertainment, and while he did just that, he also made O Brother, Where Art Thou? for Hollywood. His audience never feels outwitted; he writes in universal themes with a familiar, hair-trigger tongue, generating an onslaught of guiltless laughs. Behind it, his genius subsists. As Sullivan masquerades in his tramp garb, he could be an emblematic Sturges: a brilliant, creative intelligence in the disguise of The Common Man.

Sturges dedicates his film in the opening titles, and surely the director counted Chaplin and Lubitsch among them: “To the memory of those who made us laugh: the motley mountebanks, the clowns, the buffoons, in all times and in all nations, whose efforts have lightened out burden a little, this picture is affectionately dedicated.” The dedication reads as if Sturges has not laughed for years, or that laughs in his era are few and far between. Though Sturges was writing about his preachy fellow directors, his remarks may seem more relevant today. Certainly, if Sturges were around today, he may have a similar sense of longing for a time of wit and satire amid today’s formulaic, homogenized, gross-out, and dim-witted comedies. Fortunately, film enthusiasts can readily access Sturges’ work in lieu of some contemporary trifle. Sturges, and Lubitsch before him, played with suggestions of sex, politics, and ideas generally believed to be unfunny—certainly not representational norms in the directors’ contemporary cinema. Forging such topics into wholly popularized subject matter through humor, they made way for their successors to further push boundaries. Theirs was a cinema wherein graceful metaphor married urbane salaciousness, together creating elegant masterworks of comic wisdom. Sullivan’s Travels remains an unconventional comedy, a blend of slapstick and drama, and one of the few effective message films in any genre. Sturges set out to make entertainment, and while he did just that, he also made O Brother, Where Art Thou? for Hollywood. His audience never feels outwitted; he writes in universal themes with a familiar, hair-trigger tongue, generating an onslaught of guiltless laughs. Behind it, his genius subsists. As Sullivan masquerades in his tramp garb, he could be an emblematic Sturges: a brilliant, creative intelligence in the disguise of The Common Man.

Bibliography:

Curtis, James. Between Flops: A Biography of Preston Sturges. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, c1982.

Harvey, James. Romantic Comedy in Hollywood, from Lubitsch to Sturges. New York: Knopf, 1987.

Sturges, Preston; Sturges, Tom. Preston Sturges by Preston Sturges: His Life in His Words. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1990.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review