The Definitives

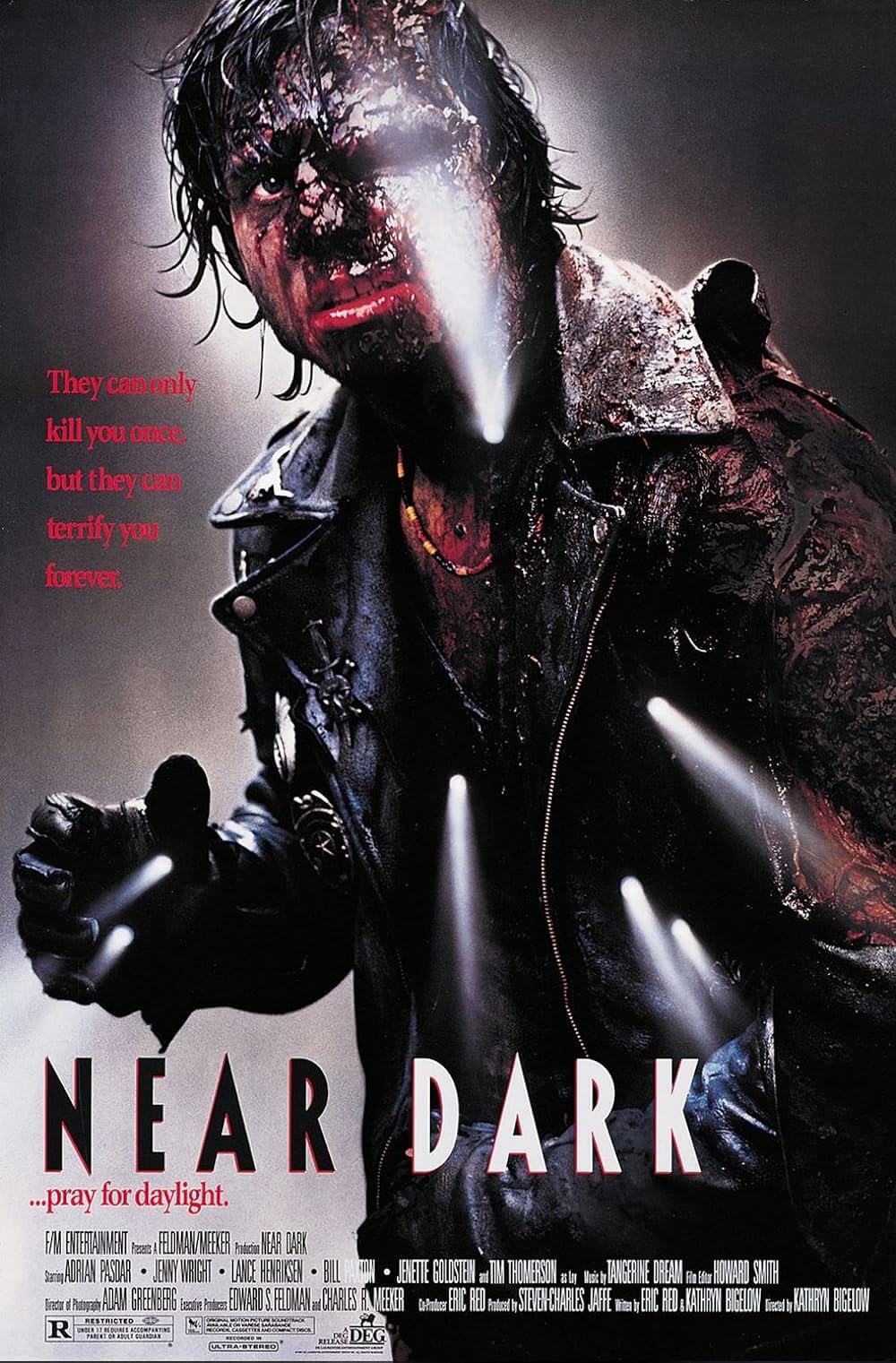

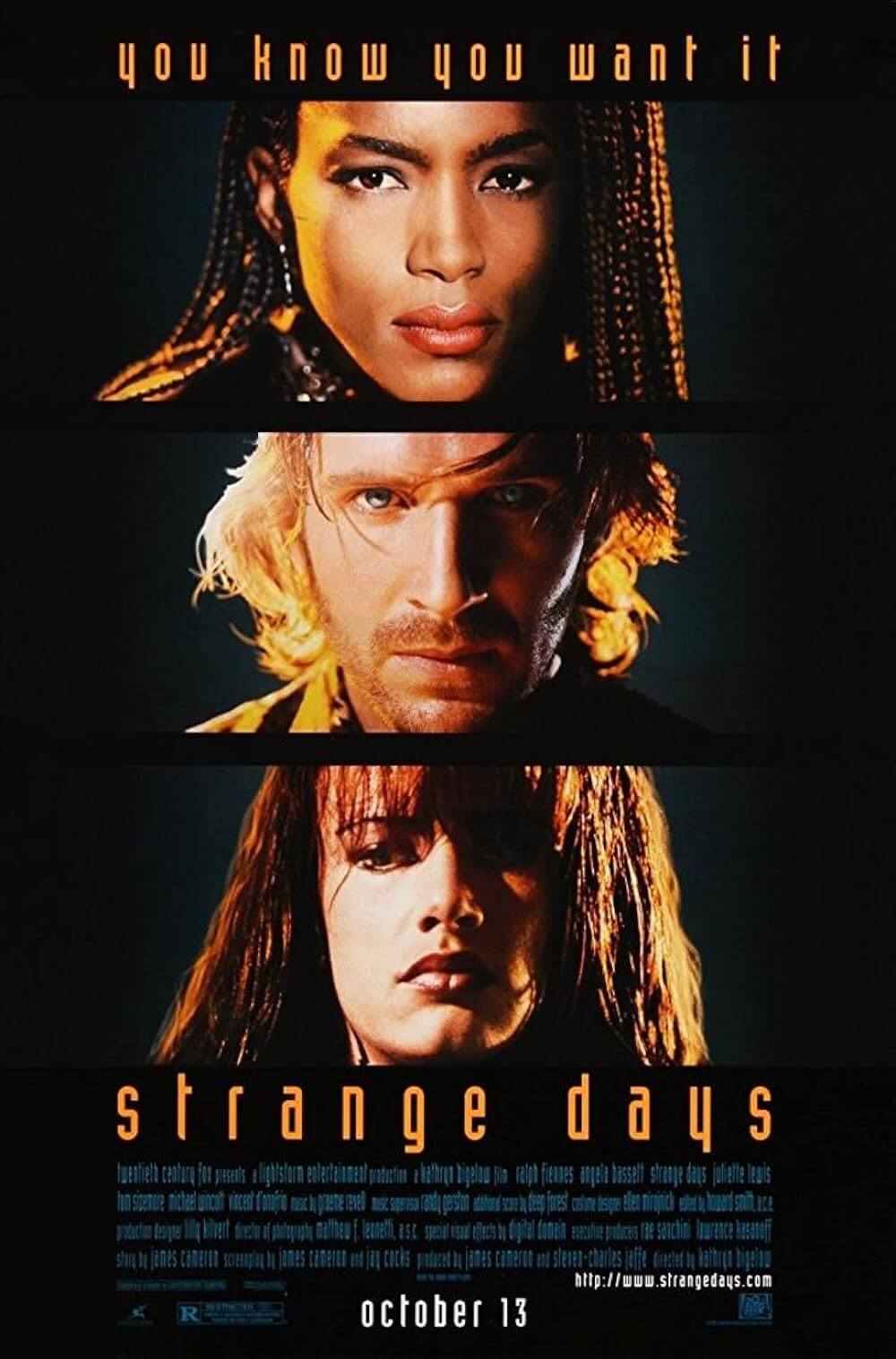

Strange Days (1995)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

“I love your eyes,” says a character in Strange Days. “I love the way they see.” In Kathryn Bigelow’s dystopian science-fiction film, people can literally see and feel the experiences of others. But these sensations include criminal acts, sexual fantasies, female victimization, and racial violence. The 1995 film reflects and anticipates a world unraveling at the dawn of a new millennium. Outside, apocalyptic anxiety has amplified racial tensions to out-of-control extremes. Inside, people distract themselves using illegal technology that allows them to inhabit another person’s experiences as an escape. Although the techno-thriller’s shared authorship between Bigelow and writer-producer James Cameron uses contemporary events and plausible tech to render a convincing future in service of a murder plot, Bigelow shapes the film’s many moving parts into a critique of traditional storytelling motifs grounded in white male fantasies. Unfortunately, Strange Days was a commercial and critical failure. But it proved so ahead of its time, so involved in its myriad of narrative threads, so full of virtuosic formal innovations, so rich in its cultural commentary, and so sybilline in its portrait of the future that its reappraisal seemed inevitable. The film remains a stunning example, arguably the finest of her career, of Bigelow’s ongoing investigation of conventional genres through a postmodern feminist framework.

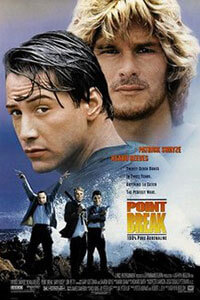

Whether labeled a film maudit or an overlooked gem, Strange Days was a box-office flop that audiences mostly ignored in 1995. Its complexity led to many critics calling its high-concept scenario “messy” or “overwhelming.” Using a cyberpunk launchpad from the modish 1990s topic of virtual reality technologies—proven to be bankable by The Lawnmower Man (1992), Disclosure (1994), and Virtuosity (1995)—the film redeploys a familiar noir storyline, complete with a former cop who investigates the rape and murder of a prostitute. If that weren’t enough, the film also takes place against the familiar but dystopic future of 1999, weaving ripped-from-the-headlines and prescient themes about police brutality, racism, and abuses of power into the story. Still, everything about Strange Days suggested a box-office success for the distributors at 20th Century Fox: Bigelow had delivered the studio’s 1991 hit, Point Break. Cameron, who supplied the story, had a track record of blockbusters to his name, most contemporaneously Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) and True Lies (1994). Ralph Fiennes, fresh off appearances in Schindler’s List (1993) and Quiz Show (1994), plus a Tony Award for his Hamlet, offered an attractive leading man. His costar Angela Bassett had beauty, strength, and talent that had just earned an Oscar nomination for What’s Love Got to Do with It (1993). Strange Days would pull these various components into an intricate and visceral two-and-a-half-hour film, all while addressing society’s fears about the impending turn of the century marking the end of everything.

In the last years before the millennium, doomsayers from religious circles to the tech community believed a global event would bring about a cataclysm at midnight on New Year’s Eve, 1999—otherwise known as Y2K, short for “year 2000.” Believing the end was nigh, people stockpiled guns, ammunition, and canned food. Televangelist Jerry Falwell warned the religious right that Y2K would be “God’s instrument” to bring about change. Many believed the rapture would suck people into the sky or Christ would return to judge the living and the dead. But the anxieties weren’t just from the fanatics; scientists worried too. Computer programmers acknowledged the real possibility that software might not be able to recognize “00” as a year. The glitch might cause a shutdown of the entire grid or wipe the global economic infrastructure to zero. So companies scrambled to reprogram their software to account for the change. Even Prince’s “1999” warned that people had better party now because the new millennium meant Endsville: “Two-thousand-zero-zero, party over, oops, out of time.” The general feeling was that humanity had reached its limit, and we would not survive. It’s a sentiment echoed by Max, Tom Sizemore’s sleazy and badly wigged Private Investigator in Strange Days: “You know how I know it’s the end of the world? Everything’s already been done. […] How are we going to make another thousand years? I’m telling you, man, it’s over. We used it all up.”

In the last years before the millennium, doomsayers from religious circles to the tech community believed a global event would bring about a cataclysm at midnight on New Year’s Eve, 1999—otherwise known as Y2K, short for “year 2000.” Believing the end was nigh, people stockpiled guns, ammunition, and canned food. Televangelist Jerry Falwell warned the religious right that Y2K would be “God’s instrument” to bring about change. Many believed the rapture would suck people into the sky or Christ would return to judge the living and the dead. But the anxieties weren’t just from the fanatics; scientists worried too. Computer programmers acknowledged the real possibility that software might not be able to recognize “00” as a year. The glitch might cause a shutdown of the entire grid or wipe the global economic infrastructure to zero. So companies scrambled to reprogram their software to account for the change. Even Prince’s “1999” warned that people had better party now because the new millennium meant Endsville: “Two-thousand-zero-zero, party over, oops, out of time.” The general feeling was that humanity had reached its limit, and we would not survive. It’s a sentiment echoed by Max, Tom Sizemore’s sleazy and badly wigged Private Investigator in Strange Days: “You know how I know it’s the end of the world? Everything’s already been done. […] How are we going to make another thousand years? I’m telling you, man, it’s over. We used it all up.”

Strange Days became a reality from a distribution deal negotiated in the early 1990s between Cameron’s production company, Lightstorm Entertainment, and the studio backers at 20th Century Fox. Although their initial deal also included True Lies and ten other features for $500 million, cash-flow problems and unreliable investors overseas caused a restructuring of the agreement (which never played out as intended). But the seed of Strange Days had been planted in the mid-1980s when Cameron first conceived the idea as “an erotic suspense thriller set in the very near future” that, according to Cameron, was also “character-based and realistic” in the style of David Mamet. He started by writing a treatment but found himself caught up in the characters and sometimes wrote out whole scenes. The result was a 131-page document he called a “scriptment,” a combination of a traditional script and a prose treatment. However, Cameron never intended to fully write or direct the project. Instead, he wanted Bigelow—his wife from 1989 to 1991, whom he met while she was making Blue Steel (1989) and continued to collaborate with after their divorce—to helm the story. In Bigelow’s hands, the material drifted away from Cameron’s usual romanticism and edged toward something more political, hard-edged, and grounded. Together, Cameron and Bigelow agreed to hire film critic and screenwriter Jay Cocks, best known for his collaborations with Martin Scorsese (The Age of Innocence, 1993; Silence, 2016), to complete the script.

Shot entirely on location in Los Angeles over the summer of 1994, Strange Days finagled impossible locations that required special permits and location fees that many productions today could not acquire, lending the film authenticity. One of the most critical sequences unfolds on Sunset Boulevard, transforming the location into a near-apocalyptic war zone. Strange Days depicts a world in the throes of collapse on December 30, 1999, and ends with a climactic New Year’s Eve party to usher in 2000. An atmosphere of rising tension and dread pervades, and paranoid end-of-the-world anxieties saturate every facet of society, evidenced by dominant warfare between races and classes—a grim portrait of an urban sprawl beset by a military presence, rioting, and chaos in the streets of Los Angeles. The scene on Sunset Boulevard follows the film’s protagonist, Lenny Nero (Ralph Fiennes), in his car in the late-night hours. A barrage of expositional radio and news broadcasts establish the period, which, in 1995, signaled the bleak future. Mentions of “gas over three bucks a gallon” and “5th-grade kids shooting each other” sound eerily familiar as of this writing in 2022. Outside his car windows, a frantic display of armored cops, police beating suspects, rogue fires, tanks, barricades, looting, heavily armed civilians, and plumes of smoke portray a world coming apart at the seams.

While aspects of the film feel grounded in a harsh reality and probable future, much of Strange Days hinges on a science-fiction technology called SQUID (superconducting quantum interference device). As one character explains, the police developed it as an alternative to a body wire, but now it thrives on the black market. The wearer places a weblike network of sensors on their head, and the device records all sensory information, including visual and physical sensations. In turn, it also allows users to experience “playback” via “clips” bought and sold illegally on the underground marketplace. Lenny deals in these recorded experiences and explains to a prospect, “This is not like TV, only better. This is life. It’s a piece of somebody’s life. It’s pure and uncut, straight from the cerebral cortex.” SQUID allows users to experience consequence-free crimes, sex without risk of disease, or even what it’s like to be another gender. But there are other uses: Lenny offers a leg amputee a clip of a man running on a beach, lending him the brief phantom sensation of feeling whole again. But most of Lenny’s clips trend toward the sensational and salacious.

While aspects of the film feel grounded in a harsh reality and probable future, much of Strange Days hinges on a science-fiction technology called SQUID (superconducting quantum interference device). As one character explains, the police developed it as an alternative to a body wire, but now it thrives on the black market. The wearer places a weblike network of sensors on their head, and the device records all sensory information, including visual and physical sensations. In turn, it also allows users to experience “playback” via “clips” bought and sold illegally on the underground marketplace. Lenny deals in these recorded experiences and explains to a prospect, “This is not like TV, only better. This is life. It’s a piece of somebody’s life. It’s pure and uncut, straight from the cerebral cortex.” SQUID allows users to experience consequence-free crimes, sex without risk of disease, or even what it’s like to be another gender. But there are other uses: Lenny offers a leg amputee a clip of a man running on a beach, lending him the brief phantom sensation of feeling whole again. But most of Lenny’s clips trend toward the sensational and salacious.

Strange Days required technical innovations to achieve the necessary look for multiple SQUID shots. These elaborate, high-energy POV sequences, captured in several immersive long takes, had to convincingly render the effect of playback—the recorded experience captured on the headsets from the SQUID wearer’s brain. Whether it’s a robbery, steamy sexual encounter, or learning to rollerblade, the moment had to appear as though someone had seen the image through their eyes. Bigelow and Cameron relied on the director of photography Matthew Leonetti to develop new technology to achieve the desired outcome, and the trial-and-error process took a year. Finally, Leonetti came up with a head-mounted camera on a helmet, and the vivid footage looks like the viewer lives inside recorded experiences. But it wasn’t just about mounting a camera on an actor’s head and setting them loose on the scene. These highly choreographed POV sequences meant the actor had to become a camera operator, and capturing the visual information with head movements to establish the setting and ensuing action required weeks of planning.

Despite the science-fiction trappings, Strange Days has all the hallmarks of a neo-noir picture. Lenny is a familiar noir character, a weaselly alternate of Richard Widmark’s desperate wheeler-dealer in Night and the City (1950). An ex-cop kicked off the police force for corruption, Lenny has become a hustler, someone who talks endlessly and always needs a favor, always has an angle, and peddles his clips, mainly with a pornographic bent. If he has any sense of morality, he doesn’t deal in “blackjack” clips—snuff clips that showcase actual deaths. In the opening scene, he experiences a clip shared by another dealer, Tick (Richard Edson), featuring a restaurant robbery that ends with the gunman, the SQUID wearer, falling from a rooftop during his escape from police officers. When the gunman dies, Lenny experiences that terror for a brief instant. And though he avoids blackjack clips, Lenny doesn’t balk at dealing with material that contains crimes, even when it’s apparent that the demand for a new and intense clip instigated the criminal act. Lenny conveniently overlooks that he ostensibly commissions crime to resell those experiences to his clientele, despite justifying his business by claiming his clips prevent users from performing criminal acts.

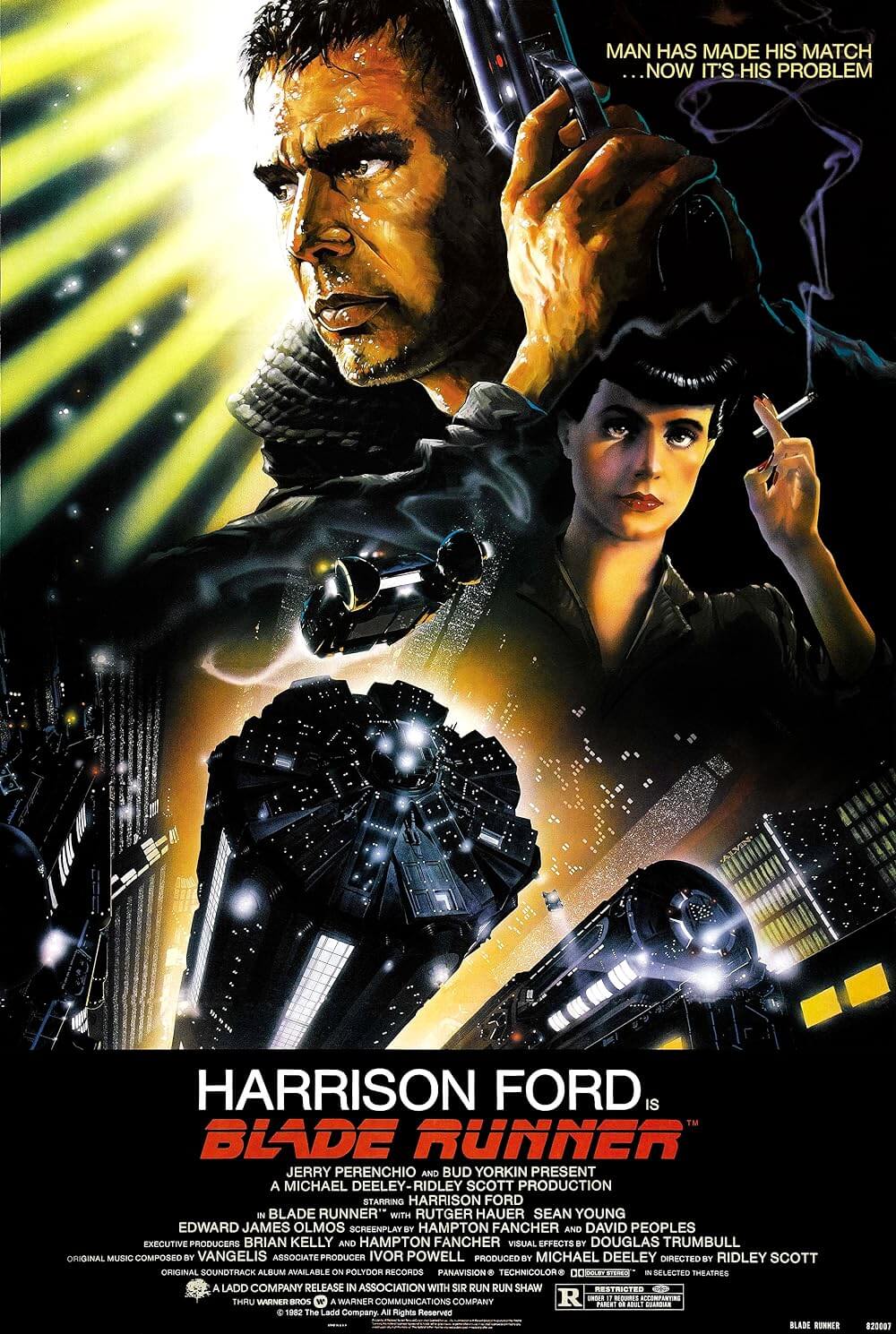

Like many noir protagonists, Lenny has taken a dark turn. When alone, he escapes into his shimmering past—not unlike the heroes of other noir-tinged science fiction: Harrison Ford’s character in Blade Runner (1982) drinks while surrounded by old photos that allude to an uncertain history; Tom Cruise loses himself in drugs and holographic family videos in Minority Report (2002). Similarly, Lenny pours himself a drink, wears SQUID gear, and watches old clips of his time with Faith (Juliette Lewis), his former lover. Faith left him for sleazy record producer Philo Gant (Michael Wincott) to launch her alt-rock career. Ever since, “Lenny the loser” has become reliant on his clips of Faith, and every hustle is a maneuver to win her back. In noir terms, Faith is a femme fatale, leading him astray. And typical of noir, Lenny’s good-hearted and practical romantic interest warns him that Faith is a bad choice. Enter Lornette “Mace” Mason (Angela Bassett), Lenny’s most reliable friend, a limousine driver and bodyguard who questions his reliance on “used emotions” and reminds him that “memories were meant to fade. They were designed that way for a reason.” Bigelow underscores Mace and Lenny’s deep bond in the film’s sole flashback, where, as a cop, he helped her overcome her husband’s arrest and looked over her young child, Xander.

Like many noir protagonists, Lenny has taken a dark turn. When alone, he escapes into his shimmering past—not unlike the heroes of other noir-tinged science fiction: Harrison Ford’s character in Blade Runner (1982) drinks while surrounded by old photos that allude to an uncertain history; Tom Cruise loses himself in drugs and holographic family videos in Minority Report (2002). Similarly, Lenny pours himself a drink, wears SQUID gear, and watches old clips of his time with Faith (Juliette Lewis), his former lover. Faith left him for sleazy record producer Philo Gant (Michael Wincott) to launch her alt-rock career. Ever since, “Lenny the loser” has become reliant on his clips of Faith, and every hustle is a maneuver to win her back. In noir terms, Faith is a femme fatale, leading him astray. And typical of noir, Lenny’s good-hearted and practical romantic interest warns him that Faith is a bad choice. Enter Lornette “Mace” Mason (Angela Bassett), Lenny’s most reliable friend, a limousine driver and bodyguard who questions his reliance on “used emotions” and reminds him that “memories were meant to fade. They were designed that way for a reason.” Bigelow underscores Mace and Lenny’s deep bond in the film’s sole flashback, where, as a cop, he helped her overcome her husband’s arrest and looked over her young child, Xander.

After introducing Lenny, the film cuts to the intersecting story: Two cops (Vincent D’Onofrio, William Fichtner) chase a white sex worker named Iris (Brigitte Bako) into a subway terminal. When they radio back to dispatch that their perp is a “Black male,” two things become evident: their chase is not official, and their blame of a Black male suspect instead of a white woman underscores their racism. When Iris narrowly escapes on the subway, the cops clutch her wig and see the SQUID recording gear inside—whatever they’ve done, she has evidence of it. After escaping, Iris seeks help from Lenny and leaves him a clip in his car. Later in the film, Bigelow reveals what Iris recorded: the death of prominent rapper Jeriko One (Glenn Plummer), who has spoken out about the LAPD’s racism and oppression of Black voices in America. The police have called the rapper’s death “gang-related,” but Iris’ clip shows a racially targeted traffic stop ending in his point-blank execution. The clip could be a bargaining chip for Lenny to exchange with Philo, Jeriko One’s manager, to get Faith back. For Mace, the clip is a “lightning bolt from God” to bring the killer cops to justice and exact real change against the racist and corrupt LAPD. It’s all the more significant that the audience doesn’t see the clip when Lenny watches it; rather, Lenny pleads with Mace to see it for herself. The audience sees the clip through Mace’s first “virgin brain” experience with SQUID tech, and in forcing the viewer to see the murder through her initiation to the tech, Bigelow introduces the moral stakes that shape the remainder of the film.

Bigelow worked with writer Cocks on Strange Days to place more emphasis on Mace and the racially charged storyline than Cameron’s original scriptment, and Cocks has insisted in interviews that Bigelow reshaped the material according to her authorial vision. In Bigelow’s hands, Mace is a source of political and racial subjectivity, which adds significance to the love triangle between Lenny, Faith, and Mace but also supplies a feminist construction. Cameron, of course, is no stranger to strong female characters who subvert patriarchal standards, as evidenced by Ellen Ripley in Aliens (1986) or Sarah Connor in Terminator 2: Judgment Day. Indeed, Mace is a muscular, capable Black woman whose male counterpart is comparatively ineffectual, soft, and unprincipled. However, unlike Lenny, Mace’s moral center remains unclouded; she’s direct, whereas Lenny tends to shirk around everything that’s not related to his agenda. She’s always there to rescue and defend him, and she never shies away from confronting him about his behavior (“Friendship is more than one person constantly doing favors for another.”) or making her contempt for his SQUID hustle apparent (“Face it. You sell porno to wireheads.”). She also proves an indomitable force when confronted—a downright badass when taking on the killer cops or Philo’s bodyguards. Bigelow further rethinks gender norms in Hollywood movies through Mace’s Black female subjectivity, reassigning power from the usual white male hero to a character who proves more complex and compelling than Lenny. She becomes what scholar Christina Lane called a “voice of critique” of the dominant ideology driving the story.

Cocks praised Bigelow’s influence over the final script, even though she received no screenwriter’s credit. Among her other contributions, the director pushed the film’s unnerving rape scenes to the limit. “She went as far as I thought was possible,” Cocks told Lane, “and then a bit further.” A mysterious killer leaves Lenny a disturbing blackjack clip that shows Iris’ rape and murder. The attacker wears SQUID gear and forces Iris to wear a headset too, and by “jacking her into his own output,” the rapist forces his victim to experience his thrill, while her terror heightens his pleasure until her death. Bigelow not only shows the clip but shows Lenny’s multifaceted reaction that combines his sensations and utter horror over what they represent—just as viewers of Strange Days must experience these layers due to the POV technique. This disturbing scene—along with a later clip of the killer placing a box cutter on Lenny’s neck while he sleeps—shows that someone wants to keep Lenny quiet about Jeriko One’s murder. He assumes it’s someone close to Philo, or Philo himself, since the paranoid and playback-obsessed record producer paid Iris to follow the rap star. However, in a climactic and expositional scene, Lenny’s former-cop friend Max, on Philo’s payroll as Faith’s bodyguard, reveals that he’s the killer, and his lover Faith helped him. However, Bigelow raises the stakes beyond the typical noir whodunit and doublecross, making Lenny’s romantic mission to save Faith and stop the killer secondary to Mace’s more political demand for justice. Bigelow allows the story to shift from Lenny’s concerns to Mace’s focus on racial justice and the prominence of reality.

Cocks praised Bigelow’s influence over the final script, even though she received no screenwriter’s credit. Among her other contributions, the director pushed the film’s unnerving rape scenes to the limit. “She went as far as I thought was possible,” Cocks told Lane, “and then a bit further.” A mysterious killer leaves Lenny a disturbing blackjack clip that shows Iris’ rape and murder. The attacker wears SQUID gear and forces Iris to wear a headset too, and by “jacking her into his own output,” the rapist forces his victim to experience his thrill, while her terror heightens his pleasure until her death. Bigelow not only shows the clip but shows Lenny’s multifaceted reaction that combines his sensations and utter horror over what they represent—just as viewers of Strange Days must experience these layers due to the POV technique. This disturbing scene—along with a later clip of the killer placing a box cutter on Lenny’s neck while he sleeps—shows that someone wants to keep Lenny quiet about Jeriko One’s murder. He assumes it’s someone close to Philo, or Philo himself, since the paranoid and playback-obsessed record producer paid Iris to follow the rap star. However, in a climactic and expositional scene, Lenny’s former-cop friend Max, on Philo’s payroll as Faith’s bodyguard, reveals that he’s the killer, and his lover Faith helped him. However, Bigelow raises the stakes beyond the typical noir whodunit and doublecross, making Lenny’s romantic mission to save Faith and stop the killer secondary to Mace’s more political demand for justice. Bigelow allows the story to shift from Lenny’s concerns to Mace’s focus on racial justice and the prominence of reality.

Science-fiction films often introduce new tech concepts, but the best of them show tech breaking down, manipulated, or misused to disturbing extremes. Strange Days fulfills this trope with Max using the SQUID technology in unsettling ways, but its placement in the narrative presents an affront to reality. That’s the concern at the story’s center, epitomized by the relationship between Lenny and Mace, between Lenny’s weakness for the tech’s fantasy world of others’ experiences, and Mace’s grounded place in the crumbling world of 1999. Lenny’s addiction to experiencing life through a fantasized filter prevents Mace from admitting her love for him; it’s contrary to everything she represents. At one point, Faith tells Lenny, “You know one of the ways that movies are still better than playback? ’Cause the music comes up, there’s credits, and you always know when it’s over.” Although she uses the line to cut ties with her ex-boyfriend, Faith’s remark underscores that playback blurs the line between fantasy and reality. Only when Lenny accepts this in the finale does he redeem himself—after turning the clip of Jeriko One’s murder over to Mace to give to the authorities, and then giving up on Faith, the personification of his dependence on fantasy. When Mace and Lenny embrace with a kiss amid the crowded New Year’s Eve celebrations in the finale, it feels earned because Lenny has set aside his obsession with living in his idealized past and accepted the reality-bound Mace’s worldview of learning from the past to make a better future.

Besides conveniently resolving the film’s many conflicts in a heightened moment, the climactic New Year’s Eve celebration, a sequence of incredible scope captured in downtown Los Angeles, is also impressive as a technical and logistical achievement. Although the sequence includes footage captured by the production’s camera crews in New York and Spain the year before, Strange Days delivers a convincingly monumental New Year’s Eve bash. The producers hired concert promoters to achieve this sprawling rave populated by a sea of moshing bodies, which today would probably be shot on a soundstage or rendered with CGI. Rather than pay thousands of extras in the crowd to fill the backdrop, promoters Moss Jacobs and Philip Blaine arranged a live performance. Groups such as Skunk Anansie, Aphex Twin, and Deee-Lite, along with several other alternative bands, headlined the live performances, which the production recorded and used in the final audio edit. Attendees paid $10 per ticket in advance sales only, parking included, and not only participated in a massive party but appeared in a major motion picture. The party spanned a four-block area, and the filmmakers dropped five tons of confetti on the rave from the Bonaventure Hotel. To control the scene, the producers employed fifty off-duty police officers and many more on-duty officers to manage thousands of real-life people who appeared in the scenes (and engaged in a concert’s usual number of fights and Ecstasy overdoses). The scene looks like the party of the century.

Still, the film’s complexity proved a hard sell. Scholar Romi Stepovich called Strange Days a “disaster” because of its marketing, which had the impossible task of reducing the many facets of its story into a simple logline. What aspect of the film should they have sold? They tried everything. A teaser trailer featured Ralph Fiennes against a white backdrop, pitching something alluring, while words such as “sensory experience” and “forbidden fruit” and “adrenaline” flash on the screen. “You know you want it,” he says, echoing his push on a businessman from the film. But what exactly audiences were supposed to want based on this pitch remained uncertain. Another trailer ham-fistedly smashed together a series of high-octane shots of guns firing, riots involving police, and other random bits of action; glimpses of sexual situations; and glib lines like “Cheer up, the world’s gonna end in ten minutes anyway”—all set to blasting guitar riffs. The trailer ends with an emphasis on the word “Strange” before the full title appears. Strange, indeed. Audiences stayed away, and Strange Days earned just under $9 million on a budget of around $45 million. The reviews were mixed, with high praise from Roger Ebert and Janet Maslin, and a range of confusion and disdain from most others.

Still, the film’s complexity proved a hard sell. Scholar Romi Stepovich called Strange Days a “disaster” because of its marketing, which had the impossible task of reducing the many facets of its story into a simple logline. What aspect of the film should they have sold? They tried everything. A teaser trailer featured Ralph Fiennes against a white backdrop, pitching something alluring, while words such as “sensory experience” and “forbidden fruit” and “adrenaline” flash on the screen. “You know you want it,” he says, echoing his push on a businessman from the film. But what exactly audiences were supposed to want based on this pitch remained uncertain. Another trailer ham-fistedly smashed together a series of high-octane shots of guns firing, riots involving police, and other random bits of action; glimpses of sexual situations; and glib lines like “Cheer up, the world’s gonna end in ten minutes anyway”—all set to blasting guitar riffs. The trailer ends with an emphasis on the word “Strange” before the full title appears. Strange, indeed. Audiences stayed away, and Strange Days earned just under $9 million on a budget of around $45 million. The reviews were mixed, with high praise from Roger Ebert and Janet Maslin, and a range of confusion and disdain from most others.

Many believe that Strange Days proved too timely for its own good, and that audiences didn’t want to see a movie that closely resembled the headlines. The killing of Jeriko One by the LAPD, followed by the officers’ continued pursuit of the recorded evidence, portrays two white cops unequivocally responsible for the murder of a Black leader and charts their murderous attempts to cover up their crime. Bigelow’s emphasis on these themes echoes the contemporary discussions about LAPD racism and the threat of race riots in Los Angeles. After all, accounts of an all-white jury’s exoneration of four white cops for the 1992 beating of Rodney King, the unarmed Black motorist whose brutalization had been caught on camera, had already inundated American media coverage. The verdict led to three days of looting and violence that left 55 African American and Hispanic community members dead, thousands injured, thousands more arrested, and the city with billions in property damage. When Mace argues that “maybe it’s time for a war” after learning of Jeriko One’s killing, she echoes feelings of the ’92 riots and their aftermath. If this theme of anger over racial injustice proved uncharacteristic of Bigelow’s career at the time, she would revisit the theme later in her career with Detroit, her 2017 picture about the Algiers Motel incident during the 1967 Detroit Riot.

Even so, the trailers for Strange Days didn’t sell a film about race relations; they focused on explosive action and the high-concept SQUID technology. Likely, the promotional material failed to narrow down any single marketable quality of the film besides its darkness, action, dystopia, and notable stars. Its box-office downfall may be attributable to the failure of ads to encapsulate its multilayered thematic structure. But its layers mark the reason that Strange Days has continued to have a long life. The film resonates more than ever, given the parallels between the 1990s American culture it reflects and the American culture of today: the prevalence of police shootings of Black men by white officers, reaching a head with the murder of George Floyd and the ensuing protests of 2020 around the world; the omnipresence of recorded experiences on social media; the popularity of VR headsets, for everything from gaming to 3D pornography; and the rise of extremist politics, threats of international war, and persistent evidence of climate change. The world of Strange Days and its sense of impending apocalypse is not so different from our own—a grim statement, to be sure.

With Strange Days, Bigelow rethinks the usual science-fiction action movie with conscious attention to questioning and reformatting gender and race roles. If Lenny redeems himself in the last moments in a race-through-the-crowd romantic embrace, it’s because he finally sees the wisdom of Mace’s ideology, and she recognizes this. The moment might seem convenient and oblivious of what’s to come after word of Jeriko One’s murderers gets out, but it’s a reward for Lenny’s adjusted mindset. It also wouldn’t be possible without Bigelow using science-fiction tech and noir narrative trajectories to critique Lenny’s privileged dependence on fantasy—a luxury Mace, as a Black woman in America, cannot afford. Ever readdressing typically masculine genres to guide her audience to a critique of storytelling norms, Bigelow delivers an entangled, challenging, and exciting film with Strange Days. Its bold amalgamation of genres, heightened visual techniques, and interwoven narrative align with her authorial vision and tendency for excess. Any of these individual aspects demand, and in some cases have earned, close consideration, and have allowed the film to endure. Yet, Bigelow’s ability to blend them under a resonant, overarching critique preserves the film and makes it more than a Hollywood product about a near-future now past, but an essential film for today.

(Note: This essay was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on June 16, 2022.)

Bibliography:

Brooker, Will. “Rescuing Strange Days: Fan Reaction to a Critical and Commercial Failure.” The Cinema of Kathryn Bigelow, edited by Deborah Jermyn, Sean Redmond, Wallflower Press, 2003, pp. 198-219.

Keough, Peter, editor. Kathryn Bigelow: Interviews. Conversations with Filmmakers Series. University Press of Mississippi, 2016.

Lane, Christina. “The Strange Days of Kathryn Bigelow and James Cameron.” The Cinema of Kathryn Bigelow, edited by Deborah Jermyn, Sean Redmond, Wallflower Press, 2003, pp. 178-197.

Shaviro, Steve. “Straight From the Cerebral Cortex: Vision and Affect in Strange Days.” The Cinema of Kathryn Bigelow, edited by Deborah Jermyn, Sean Redmond, Wallflower Press, 2003, pp. 159-177.

Stepovich, Romi. “Strange Days: A Case History of Production and Distribution Practices in Hollywood.” The Cinema of Kathryn Bigelow, edited by Deborah Jermyn, Sean Redmond, Wallflower Press, 2003, pp. 144-158.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review