The Definitives

State and Main (2000)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Before even the first shots of principal photography, production on “The Old Mill” has stopped. Another of leading man Bob Barrenger’s incidents with an underage girl has forced the production to pack up and bolt in fear of scandal. They move the shoot from a no-longer-sleepy New Hampshire town to the never-heard-of-it hollow of Waterford, Vermont. “Where is it?” the film’s director says into his phone, “That’s where it is.” Waterford, like the previous locale, is a slice of small-town Americana ripe for their story about a firefighter and nun, purity, and second chances. A picturesque hamlet of unlocked doors and Rockwellian townsfolk, Waterford comes equipped with its own old mill, and therein removes the production’s need to build a costly set. Great expense has already been paid to move the shoot and quiet Barrenger’s teenage conquest; there’s no more money to spend, not on sets anyway. Dejected and tense, the screenwriter wonders if this Hollywood fiasco might compromise his story’s integrity. His anxiety is not unwarranted when the producer is informed that Waterford’s old mill burned down four decades ago, in fact. But moving the cast and crew again is out of the question. And so, the director asks his screenwriter, “Does it have to be an old mill?”

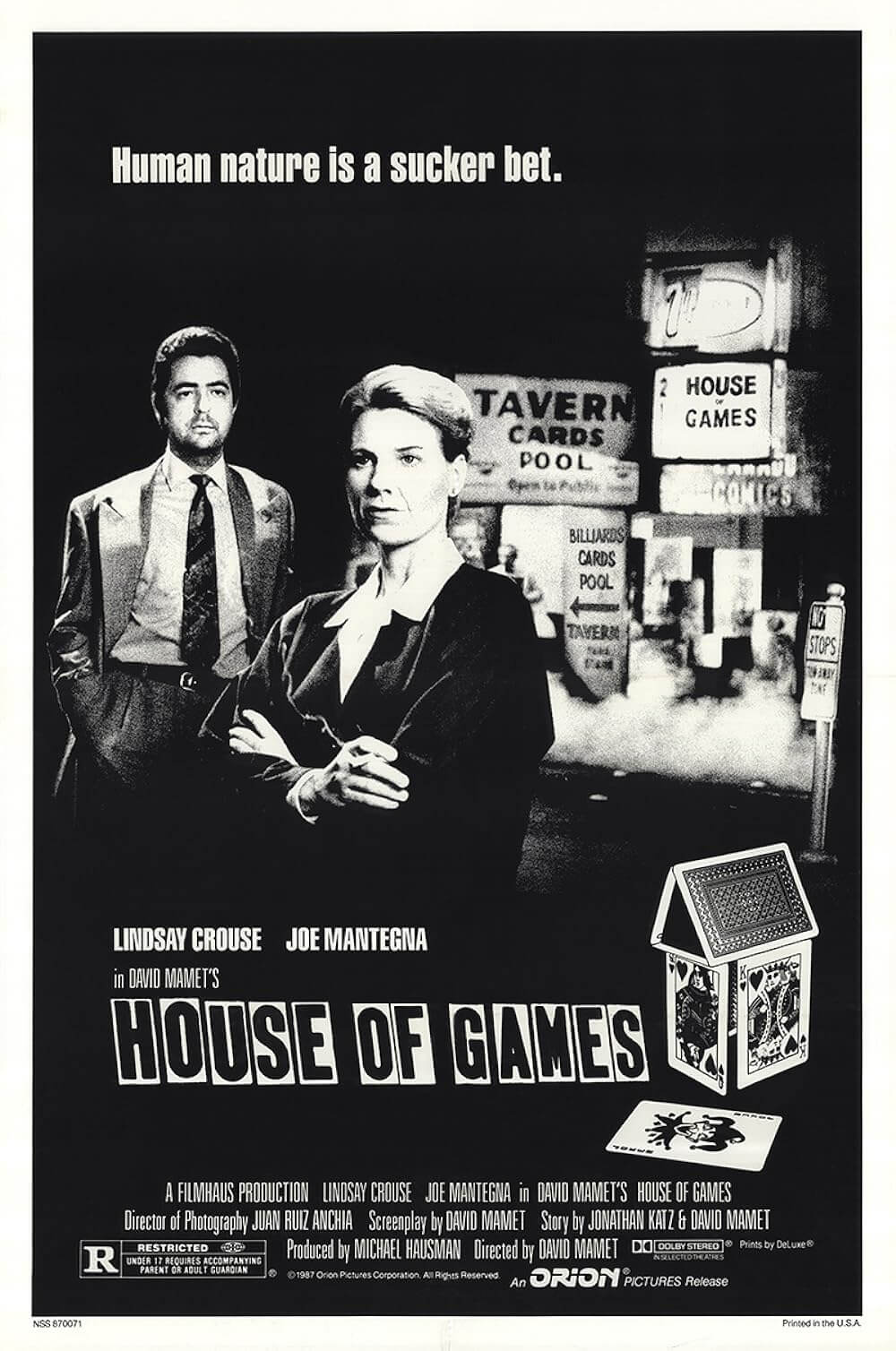

This line, like so many other hilarious and quotable witticisms in David Mamet’s State and Main, sits just under the surface and does not overemphasize itself. The film may be the sharpest of all Hollywood satires, a comedy that recognizes the equally chaotic and creative process of filmmaking, while also offering a scathing perspective on a film’s behind-the-scenes challenges and the types who populate a film production: from idealist writers to terse directors, from celebrity talent to the throwaway associate producers, from the cinematographer who wants to complete an impossible shot to the locals desperate for a walk-on role. Released in 2000, the film represents a lively departure for Mamet, the playwright and filmmaker whose output is defined by his distinct and barbed staccato dialogue dubbed “Mametspeak”. His earlier pictures, such as House of Games (1987) and The Spanish Prisoner (1997), or his later films, such as Heist (2001) and Redbelt (2008), often revolve around elaborate con games, high crime, and heavy theatrics in the characteristic style of his dramaturgy. But State and Main is completely different, playful even, and on this his seventh turn as director and umpteen effort as a screenwriter, Mamet almost seems to step back from being a filmmaker to depict what he has learned about the industry with his playwright’s wit.

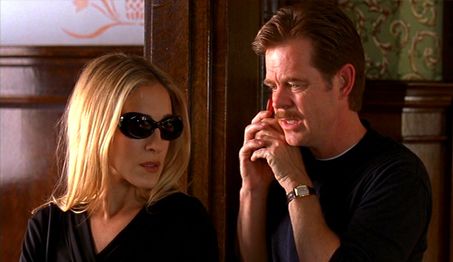

State and Main orbits around the film production, a character unto itself headed by the sly devil director named Walt Price (William H. Macy). Walt finagles his production to completion by any means necessary. Early on, he’s relieved to have his pillow, which says “Shoot first. Ask questions afterward,” delivered, and he arrives in Waterford optimistic about the possibilities. That there’s no old mill is a minor detail at this point. Now that he’s committed, and as the rest of his cast and crew arrive in Waterford, he must contend with the egos of his superstar talent—the wandering eyes of Bob Barrenger (Alec Baldwin) and the emotionally fragile celebrity of Claire Wellesley (Sarah Jessica Parker). Along with his producer Marty (David Paymer), he’s also forced to humor the locals and their old-fashioned little world, an idyllic place where the local sports team’s motto (“Go You Huskies!”) has become the customary greeting. Mamet even named the resident mayor, George Bailey (Charles During), after James Stewart’s character in It’s a Wonderful Life. Bailey’s spouse (Patti LuPone) wants an exclusive dinner party with the production’s top talent at the historic Bailey home, an event Walt knows he must attend to get a low price tag on the Main Street shooting permit. Through it all, Walt shifts his personality to fit whomever he’s talking to: he’s a down-to-earth man’s man with Bob; a soft-voiced spiritualist with Claire; a hard-nosed businessman with Marty. He’ll be anyone or say anything to make his film.

State and Main orbits around the film production, a character unto itself headed by the sly devil director named Walt Price (William H. Macy). Walt finagles his production to completion by any means necessary. Early on, he’s relieved to have his pillow, which says “Shoot first. Ask questions afterward,” delivered, and he arrives in Waterford optimistic about the possibilities. That there’s no old mill is a minor detail at this point. Now that he’s committed, and as the rest of his cast and crew arrive in Waterford, he must contend with the egos of his superstar talent—the wandering eyes of Bob Barrenger (Alec Baldwin) and the emotionally fragile celebrity of Claire Wellesley (Sarah Jessica Parker). Along with his producer Marty (David Paymer), he’s also forced to humor the locals and their old-fashioned little world, an idyllic place where the local sports team’s motto (“Go You Huskies!”) has become the customary greeting. Mamet even named the resident mayor, George Bailey (Charles During), after James Stewart’s character in It’s a Wonderful Life. Bailey’s spouse (Patti LuPone) wants an exclusive dinner party with the production’s top talent at the historic Bailey home, an event Walt knows he must attend to get a low price tag on the Main Street shooting permit. Through it all, Walt shifts his personality to fit whomever he’s talking to: he’s a down-to-earth man’s man with Bob; a soft-voiced spiritualist with Claire; a hard-nosed businessman with Marty. He’ll be anyone or say anything to make his film.

But if there’s a central protagonist in State and Main, it must be Joseph Turner White (Philip Seymour Hoffman). Some kind of cruel joke is being played on this artist, the sensitive writer whose eminent play, Anguish, earned him minor enough renown to garner his first Hollywood writing gig. The old mill is the metaphor for his entire screenplay, and yet the ironic “Does it have to be an old mill?” becomes the moniker stenciled on the crew’s t-shirts throughout the production, a constant reminder that Joe will sacrifice the purity of his story (and much more). He wanders about Waterford gloomily, his manual typewriter lost in the move from New Hampshire, and finds local bookstore owner Ann (Rebecca Pigeon). She’s heard of Joe, fixes a used typewriter for him, and begins to judge her political-minded fiancé Doug (Clark Gregg) against him. The typewriter—and soon Ann’s affinity for staging local theater productions, and therein her desire to help Joe work out the story of “The Old Mill” without an old mill—become the meet-cute by which she and Joe fall for one another, she enamored by his artistry, he taken by her small-town humanism and charm. Watch the scenes between them, how Joe is almost speechless in her presence, yet Ann always has a line for him, some sampling of rural truth embedded into their subtly romantic banter. “How do I do a film called ‘The Old Mill’ when I don’t have an old mill?” Joe asks. Ann responds, coyly, “Well, first, you’ve got to change the title.” Joe’s torture grows worse when he witnesses a car crash involving Barrenger and yet another teenaged girl (Julia Stiles), and he must decide whether to tell the truth, and in that ruin his career by halting the production of his first movie, or lie and deny having seen anything.

Mamet’s observations about the impurity of celebrity and filmmaking are hilarious, many of them contained within Walt’s duplicity and willingness to say anything to keep the production moving forward. Mamet once reflected, “Good and evil do exist in the world. For example, I think children are basically good. And on the other side of the scale, you have movie producers.” Before long, even Joe is convinced, “Maybe it’ll be a better film without the old mill.” Or consider the subplot involving Claire, who, playing a nun and claiming artistic dignity, refuses to perform her contracted nude scene and bear her breasts on camera, unless of course, she receives another $800,000. Someone points out that America could “draw her breasts from memory”. Nevertheless, Walt and Marty want her “tits” in the picture, but where can they get the money? Marty suggests a product placement for a dot-com company willing to pay one million dollars if their company’s name appears in the film. The question is, how can Walt make “Bazoomer.com” blend into the mise-en-scène of the film’s nineteenth-century backdrop? At the same time, Joe and Ann work out how to tell the story without an old mill, and furthermore without Claire having to show her “tits” onscreen. When his “Eureka!” moment comes, his reward for saving the production and the added expense of paying Claire is an associate producer credit. What’s an associate producer, you ask? “An associate producer credit is what you give your secretary instead of a raise,” one crewmember quips. Mamet ensures that from here on out you’ll look on with indignation at every associate producer credit you see.

Mamet’s observations about the impurity of celebrity and filmmaking are hilarious, many of them contained within Walt’s duplicity and willingness to say anything to keep the production moving forward. Mamet once reflected, “Good and evil do exist in the world. For example, I think children are basically good. And on the other side of the scale, you have movie producers.” Before long, even Joe is convinced, “Maybe it’ll be a better film without the old mill.” Or consider the subplot involving Claire, who, playing a nun and claiming artistic dignity, refuses to perform her contracted nude scene and bear her breasts on camera, unless of course, she receives another $800,000. Someone points out that America could “draw her breasts from memory”. Nevertheless, Walt and Marty want her “tits” in the picture, but where can they get the money? Marty suggests a product placement for a dot-com company willing to pay one million dollars if their company’s name appears in the film. The question is, how can Walt make “Bazoomer.com” blend into the mise-en-scène of the film’s nineteenth-century backdrop? At the same time, Joe and Ann work out how to tell the story without an old mill, and furthermore without Claire having to show her “tits” onscreen. When his “Eureka!” moment comes, his reward for saving the production and the added expense of paying Claire is an associate producer credit. What’s an associate producer, you ask? “An associate producer credit is what you give your secretary instead of a raise,” one crewmember quips. Mamet ensures that from here on out you’ll look on with indignation at every associate producer credit you see.

Mamet portrays Hollywood as a corruptive force, but as the film progresses, he reveals the people of Waterford to be just as impure. From Doug’s perspective, the production contaminates everything it touches, exploiting the wholesome, film-naïve town and its simple people to ensure cheap shooting costs. We see Hollywood’s corruptive power when it distorts Joe’s pure vision and transforms it into an absurd necessity to make “The Old Mill” without an old mill, or how Barrenger exploits a virginal teenager. But Mamet shows us that while the Stiles character may be virginal, she’s not innocent—she targets Barrenger outright and implies their affair will be confidential. To be sure, everyone is susceptible to the charms of the movie business, like the two Waterford old-timers who go from reading the local newspaper to debating box-office statistics from the pages of Variety. Still, Joe sees Waterford as a symbol of purity, their town newspaper bearing the motto “You Shall Not Bear False Witness” on its front page. Soon a media scandal erupts around Barrenger’s underage exploits, spearheaded by the idealistic Doug who wants only to further his political career in the scandal’s wake. And when Joe must give testimony on the incident with Barrenger and the teen, he gives up his own purity when he lies and perjures himself, only to discover his testimony was given in a courtroom setting staged by Ann so he could get the desire to lie out of his system. This twist is a signature Mamet-style con and becomes, charmingly, a romantic gesture by Ann to preserve Joe’s honesty. As for Doug, even he proves impure when he accepts the $800,000 meant for Claire—no longer needed thanks to Joe’s rewrite—as a bribe to retract his case against Barrenger.

Regardless of State and Main’s theme about purity or the illusion thereof, the hallmark of any Mamet film is the dialogue. His characters speak in snappish, half-finished sentences and use other-worldly phraseology found only in “Mametspeak”. No one in the real world talks like Mamet’s characters, and only actors of profound skill can make his dialogue sound natural. Macy, who, along with Mamet, founded the St. Nicholas Theater Company in Chicago, has appeared in a half-dozen of Mamet’s films and even more of his stage plays. He delivers Mamet’s dialogue like few others can (on the shortlist belongs Baldwin, Joe Mantegna, and Gene Hackman). “It’s not a lie. It’s a gift for fiction,” Walt defends in one scene, Mamet’s dialogue both memorable on its own and humorous for its placement. Wisdom and irony purvey such words, a double meaning for every line. Throughout State and Main, we stop to regard the two old-timers reading the paper in a local diner or walking down the street: one observes, “It takes all kinds.” The other asks, “Is that what it takes? I always wondered what it took.” And, in perhaps the film’s funniest scene, a child approaches Bob Barrenger and asks him for an autograph. “What are your hobbies,” says Barrenger. The boy replies, “Baseball,” and Baldwin pauses, a long pause that fills us with anticipation for his down-home, all-American response as he observes, “Baseball… That’s the national sport” with all sincerity.

Regardless of State and Main’s theme about purity or the illusion thereof, the hallmark of any Mamet film is the dialogue. His characters speak in snappish, half-finished sentences and use other-worldly phraseology found only in “Mametspeak”. No one in the real world talks like Mamet’s characters, and only actors of profound skill can make his dialogue sound natural. Macy, who, along with Mamet, founded the St. Nicholas Theater Company in Chicago, has appeared in a half-dozen of Mamet’s films and even more of his stage plays. He delivers Mamet’s dialogue like few others can (on the shortlist belongs Baldwin, Joe Mantegna, and Gene Hackman). “It’s not a lie. It’s a gift for fiction,” Walt defends in one scene, Mamet’s dialogue both memorable on its own and humorous for its placement. Wisdom and irony purvey such words, a double meaning for every line. Throughout State and Main, we stop to regard the two old-timers reading the paper in a local diner or walking down the street: one observes, “It takes all kinds.” The other asks, “Is that what it takes? I always wondered what it took.” And, in perhaps the film’s funniest scene, a child approaches Bob Barrenger and asks him for an autograph. “What are your hobbies,” says Barrenger. The boy replies, “Baseball,” and Baldwin pauses, a long pause that fills us with anticipation for his down-home, all-American response as he observes, “Baseball… That’s the national sport” with all sincerity.

More than any other Mamet film, State and Main is at its purest a comedy, whereas the director’s other films often contain comic moments or humor but are not comedies outright. In Things Change (1988), Joe Mantegna treats a soon-to-be-imprisoned shoe shiner to his last weekend of freedom in a frivolous getaway, but contained within are sobering themes of honor and friendship. His Pulitzer Prize-winning play Glengarry Glen Ross was turned into a phenomenal film in 1992, and its audience cannot help but uncomfortably laugh at the harsh exchanges between desperate real estate salesmen. The Mamet screenplay that most closely relates to State and Main was not directed by the man himself but rather by Barry Levinson in the 1997 political satire Wag the Dog. Mamet based his screenplay on a book by Larry Beinhart, and in the film Robert De Niro’s political spin doctor enlists Dustin Hoffman’s Hollywood producer to cover up a presidential sex scandal. Through the escalating keeps-getting-worse situations, Hoffman’s producer reassures De Niro’s character with “This is nothing” no matter the extreme nature of the calamity. State and Main’s Walt Price combines Wag the Dog’s spin doctor and movie producer into one biting, unforgettable character who has already been pushed too far before Mamet’s film opens. “Who designed these costumes?” he asks in one scene. “It looks like Edith Head puked, and that puke designed these costumes.” Meanwhile, around him scurry countless producers and gophers and people with clipboards, and he concerns himself with getting the picture in the can at any cost, as long as it’s under cost.

Mamet’s style of comedy isn’t forthright. Like a magician, he misdirects the viewer’s attention and redirects it around the gag, be it visual or embedded in the dialogue. Mamet’s sense of humor does not press the jokes or wit. Take the gag outlined in the introduction. The events have been spelled out for you, the reader, but the viewer at first isn’t told that Joe’s screenplay is called “The Old Mill”. At first, the humor isn’t apparent until, later in the film, we learn the script’s title. The punch line comes in a roundabout way, making the film funnier upon reflection and subtle in its comedic misdirection. Mamet’s jabs also come from unexpected directions. After Joe defends Claire, who’s being pressed by the filmmakers to meet the terms in her contract and show her breasts on camera, she disrobes in Joe’s room. In a familiar rom-com situation, Ann enters and sees a naked Claire in her would-be beau’s hotel room. Joe nervously offers a truthful explanation—that Claire entered his room uninvited and just started taking off her clothes. He asks if Ann believes him. “Yes,” she replies. “But that’s absurd,” he argues against himself. “So is our electoral process,” Ann says, “But we still vote.” There are dozens of lines like this, each one funnier than the last, each one insightful yet satiric and a little outlandish, and each one even more comical upon repeated viewings.

Mamet’s style of comedy isn’t forthright. Like a magician, he misdirects the viewer’s attention and redirects it around the gag, be it visual or embedded in the dialogue. Mamet’s sense of humor does not press the jokes or wit. Take the gag outlined in the introduction. The events have been spelled out for you, the reader, but the viewer at first isn’t told that Joe’s screenplay is called “The Old Mill”. At first, the humor isn’t apparent until, later in the film, we learn the script’s title. The punch line comes in a roundabout way, making the film funnier upon reflection and subtle in its comedic misdirection. Mamet’s jabs also come from unexpected directions. After Joe defends Claire, who’s being pressed by the filmmakers to meet the terms in her contract and show her breasts on camera, she disrobes in Joe’s room. In a familiar rom-com situation, Ann enters and sees a naked Claire in her would-be beau’s hotel room. Joe nervously offers a truthful explanation—that Claire entered his room uninvited and just started taking off her clothes. He asks if Ann believes him. “Yes,” she replies. “But that’s absurd,” he argues against himself. “So is our electoral process,” Ann says, “But we still vote.” There are dozens of lines like this, each one funnier than the last, each one insightful yet satiric and a little outlandish, and each one even more comical upon repeated viewings.

With an incredible ensemble cast giving deft performances and an inventory of unforgettable, achingly funny dialogue, Mamet’s film paints Hollywood types as acid-tongued, unfeeling, and ridiculous; they’re amoral and buyable, mirroring the impurity and ever-changing status of art, namely filmmaking. State and Main might even make an outstanding stage play if it weren’t for the necessity of the film production scenes, and it might be more mainstream if it weren’t so intelligent, so completely an arthouse effort, or so full of cryptic turns and cynicism behind every character. At its center, Mamet’s film is about purity within a film in which no one is pure. Not even in the seemingly innocent Waterford, where young idealists sell out, teenaged girls seduce older men, and the town’s history is littered with deranged teenagers who light old mills on fire. From a playwright whose words and dramaturgy have been singularly identified among the greats of his time, State and Main considers the madhouse process of a Hollywood production and, through its ugliness, relates such corruptive power and basic impurity to something inherent to human nature, if exaggerated here, albeit slightly, for comic effect.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review