The Definitives

Singin’ in the Rain (1952)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Classic Hollywood productions rarely had two directors, and if they did, the result was a studio creation and not shaped by the vision of a single auteur. The exception is Singin’ in the Rain, the 1952 release from co-directors Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen, which remains distinguished from the frivolous Classical Hollywood musicals of the era. Though it was developed as a standard production within the studio system, the film contains a rare harmony between its narrative and musical elements, demonstrating how they could be merged, and therein enhanced, through their integration on film. Decades after its debut, many film scholars and critics consider it the greatest of all Hollywood musicals, attributing its authorship to Kelly. But how exactly does Singin’ in the Rain differ from the typical musical, and why has it earned such an esteemed reputation? How did Kelly and Donen, overseeing hundreds of talented players and technicians, somehow make a film that seems to come from a distinct creative voice, even working within the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer musical factory? What was Kelly and Donen’s working relationship like, and how was a singular vision achieved? These answers can only be found by exploring the story behind the film; the careers of Kelly and Donen, and how they worked together; their implementation of song and dance into the narrative; and specific sequences in the film. This historical and critical analysis will show the film’s production and directorial collaboration to have been guided predominantly by Kelly’s vision to at once elevate and popularize the art of dance in cinema, yet render it in a joyous and accessible way.

To understand why Singin’ in the Rain stands apart, the Classic Hollywood musical itself requires characterization. In musicals of the period, dreams came true and love conquered all, making them the most entertaining and escapist features available to audiences. But in terms of story, they were the most lighthearted genre. They showcased popular melodies, a variety of dancing styles, and romantic comedy more than narrative or character. Traditional Hollywood musicals, especially efforts from the 1920s and 1930s, used a loose framework and treated their songs like interludes within the story. Although Broadway provided the source material for many musicals of the era, most musicals contained thin plotting and characters within a romantic comedy structure, the films serving an indulgence of music and dance first, the story second. Their considerable budgetary requirements meant most musicals were “A” pictures, and the most inventively shot, with the latest technical advances in sound and camera supporting their productions. Among the major Hollywood studios, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer was the premier musical factory in the 1940s, especially after Vincente Minnelli’s 1944 breakthrough Meet Me in St. Louis, an elaborate spectacle filmed in three-strip Technicolor—most of the studio’s musicals were shot in the expensive three-strip process after its success. MGM also housed the greatest group of musical talents in Hollywood history (including Judy Garland, Fred Astaire, Frank Sinatra, and Minnelli), releasing many of the era’s most iconic musicals, such as The Wizard of Oz in 1939 and Charles Walters’ 1948 Easter Parade.

As an MGM musical of the Classical Hollywood era, Singin’ in the Rain relies on the talents of several artists and craftsmen contracted with the studio—237 creative people in all—each providing unique skills that, through their combination in the studio system, amounts to collaborative production. Contracted studio talent including Kelly, Donald O’Connor, Cyd Charisse, Debbie Reynolds, and Jean Hagen appear in front of the camera. Kelly served as the central actor, dancer, choreographer (besides his assistant Carol Haney) and, together with Donen, the co-director. Along with sundry other writing and acting collaborations, Kelly and Donen co-directed On the Town in 1949 and teamed again in 1955 for It’s Always Fair Weather. Arthur Freed served as producer of Singin’ in the Rain; along with his music writing partner Nacio Herb Brown, Freed had written the lyrics to most of the film’s songs in the 1920s. Roger Edens arranged and updated the Freed-Brown songs for the film, having been a jazz musician for the Red Nichols Orchestra; he later became a vocal arranger for actress and singer Ethel Merman, which brought him the attention of Freed. Having photographed On the Town for Kelly and Donen, cinematographer Harold Rosson shot the picture in three-strip Technicolor. And, to be sure, many other studio personnel contributed to the production, most of them with prior connections to Freed or Kelly, making the film a collaborative studio effort just like many productions in Classical Hollywood.

As an MGM musical of the Classical Hollywood era, Singin’ in the Rain relies on the talents of several artists and craftsmen contracted with the studio—237 creative people in all—each providing unique skills that, through their combination in the studio system, amounts to collaborative production. Contracted studio talent including Kelly, Donald O’Connor, Cyd Charisse, Debbie Reynolds, and Jean Hagen appear in front of the camera. Kelly served as the central actor, dancer, choreographer (besides his assistant Carol Haney) and, together with Donen, the co-director. Along with sundry other writing and acting collaborations, Kelly and Donen co-directed On the Town in 1949 and teamed again in 1955 for It’s Always Fair Weather. Arthur Freed served as producer of Singin’ in the Rain; along with his music writing partner Nacio Herb Brown, Freed had written the lyrics to most of the film’s songs in the 1920s. Roger Edens arranged and updated the Freed-Brown songs for the film, having been a jazz musician for the Red Nichols Orchestra; he later became a vocal arranger for actress and singer Ethel Merman, which brought him the attention of Freed. Having photographed On the Town for Kelly and Donen, cinematographer Harold Rosson shot the picture in three-strip Technicolor. And, to be sure, many other studio personnel contributed to the production, most of them with prior connections to Freed or Kelly, making the film a collaborative studio effort just like many productions in Classical Hollywood.

More even than Kelly or Donen, Singin’ in the Rain would not have been possible without Arthur Freed. The Freed-Brown team wrote the titular song for the Hollywood Music Box Revue of 1927, an elaborate stage show of comedians, dancers, showgirls, and singers. Around this time, Warner Brothers’ The Jazz Singer in 1927, a largely silent picture with some moments of synchronized singing and dialogue recorded on disc, became a massive hit. Following its success, other studios began to integrate musical soundtracks and, in time, dialogue into their productions. Freed and Brown had been working as pianists to set the mood on silent film sets. When MGM production head Irving Thalberg heard about the talent of the Freed-Brown team, he hired them as musicians and songwriters, enlisting them to produce a number of “Broadway Melody” pictures for MGM that showcased popular stage hits on the screen.

As Freed and Brown’s success grew with their catalog of popular tunes, Freed established himself as a Hollywood producer. Their song “Singin’ in the Rain” was first used on film in The Hollywood Revue of 1929, a cinematic version of the earlier stage show. MGM would continue to use the song in several pictures over the years, with covers sung by Cliff Edwards, Jimmy Durante, and Judy Garland. Freed soon established his own production division at MGM, called the Freed Unit, to develop and oversee musicals based on Broadway hits or the Freed-Brown catalog. The Freed Unit was responsible for most major MGM musicals of Hollywood’s Golden Age, earning the studio vast profits from postwar audiences desperate to escape into a musical, especially one starring contract players like Kelly or Fred Astaire. Singin’ in the Rain was just one of many Freed productions. And by the time of its release, the song’s popularity was such that, upon seeing the film’s title, audiences would recognize its apostrophic slang and easily recall its melody.

Kelly and Donen would co-direct the picture, but their respective upbringings, individual concentrations of study, and arrival in Hollywood provide essential background to their working relationship. Kelly was born in 1912 in Pittsburgh, where he studied tap dancing at his family’s studio in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, while also performing in legion halls and various clubs before moving on to vaudeville, and eventually ballet. Kelly studied under celebrated Diaghilev dancer and instructor Alexander Kotchetovsky in the early 1930s; at the same time, he appeared in a number of successful shows in Pittsburgh, and earned a reputation as both a performer and instructor at tap and ballet studios he opened in the area. In 1938, Kelly moved to New York and, starring in numerous Broadway hits, met Freed, who would eventually bring the dancer to Hollywood for his debut in Busby Berkeley’s 1942 musical For Me and My Gal. While being a creative disappointment, For Me and My Gal demonstrated Kelly’s talent for song and dance, landing him several leading roles over the next decade: Cover Girl (1944), Anchors Aweigh (1945), The Pirate (1948), and An American in Paris (1951).

Kelly and Donen would co-direct the picture, but their respective upbringings, individual concentrations of study, and arrival in Hollywood provide essential background to their working relationship. Kelly was born in 1912 in Pittsburgh, where he studied tap dancing at his family’s studio in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, while also performing in legion halls and various clubs before moving on to vaudeville, and eventually ballet. Kelly studied under celebrated Diaghilev dancer and instructor Alexander Kotchetovsky in the early 1930s; at the same time, he appeared in a number of successful shows in Pittsburgh, and earned a reputation as both a performer and instructor at tap and ballet studios he opened in the area. In 1938, Kelly moved to New York and, starring in numerous Broadway hits, met Freed, who would eventually bring the dancer to Hollywood for his debut in Busby Berkeley’s 1942 musical For Me and My Gal. While being a creative disappointment, For Me and My Gal demonstrated Kelly’s talent for song and dance, landing him several leading roles over the next decade: Cover Girl (1944), Anchors Aweigh (1945), The Pirate (1948), and An American in Paris (1951).

Unlike Kelly, Donen’s interests in cinema preceded his involvement in dance and the stage. Born in 1924, Donen was raised in Columbia, South Carolina, in a town that did not welcome people of his Jewish heritage; and so, as a boy, he escaped through radio plays, music, and the cinema, particularly the films of Fred Astaire. He received an 8mm camera from his father as a gift, and he experimented with making home movies, implanting his desire to become a filmmaker early in life. Still, following his interest in Astaire and dancing, Donen studied dance locally. His mother, who had taken him to New York to see several stage shows, soon encouraged her son to move and pursue Broadway, which he did, even though his true calling was filmmaking. Donen met Kelly during the hugely popular 1940 stage production of Pal Joey on Broadway, and Kelly eventually asked Donen, then just in his mid-teens, to join him in Hollywood as his assistant. Donen worked almost exclusively on MGM musicals for more than a decade. As the years passed, Donen became progressively more interested in the technical aspects of filmmaking, and he explored other genres in the latter part of his career: the blithe Hitchcockian thriller in Charade (1963) and Arabesque (1966); the romantic drama with Indiscreet (1958) and Two for the Road (1967); and even, much later, the Lionel Richie music video “Dancing on the Ceiling” (1986).

As early as 1949, Freed began developing a project intended to use several famous Freed-Brown songs, including “Singin’ in the Rain.” Freed proposed a screen story based on the silent film Excess Baggage (1928), about a romance between a dancer and an acrobat. The treatments drawing from Excess Baggage proved uninspired, and so Freed resolved to leave the screen story to more experienced writers. In May of 1950, Freed hired Broadway-turned-Hollywood writers Betty Comden and Adolph Green to write a screenplay, which he intended Donen to direct. After considering other ideas such as a Western story or a remake of a different preexisting film, Comden and Green found themselves inspired by the career of silent film actor John Gilbert, whose celebrity was ruined when his nasally, underwhelming voice in talkies did not match his debonair good looks. Comden and Green conceived a story to match the optimism of the central song, settling on the idea of a silent film star who at first struggles with the advent of sound in motion pictures, but rather than give up, he becomes a star of talkies.

Being cinephiles, Comden and Green worked at the studio alongside Donen and watched dozens of silent era pictures for ideas. Their writing continued for months until they turned in their final draft in October 1950. Though the screenplay would undergo several revisions during production, Comden and Green provided the film’s foundational narrative so that, even without the songs, the narrative’s substance would remain enjoyable and engaging. Meanwhile, Freed waited until January 1951, when Kelly was done making An American in Paris, before asking him to join Singin’ in the Rain, and the performer’s response was so enthusiastic that he came to their initial meeting with several ideas about the script, dance numbers, and hopes to co-direct. As the film moved from development into the pre-production phase, Freed secured MGM talents on Kelly’s recommendation, including Donald O’Connor, a former vaudeville star; Cyd Charisse, a famous ballet star and MGM dancer; and Debbie Reynolds, a 19-year-old up-and-comer whom the studio wanted to develop into a star. And while Freed originally conceived Singin’ in the Rain as another MGM spectacle featuring the songs he co-wrote with Brown, the film’s trajectory changed when Kelly was hired.

Being cinephiles, Comden and Green worked at the studio alongside Donen and watched dozens of silent era pictures for ideas. Their writing continued for months until they turned in their final draft in October 1950. Though the screenplay would undergo several revisions during production, Comden and Green provided the film’s foundational narrative so that, even without the songs, the narrative’s substance would remain enjoyable and engaging. Meanwhile, Freed waited until January 1951, when Kelly was done making An American in Paris, before asking him to join Singin’ in the Rain, and the performer’s response was so enthusiastic that he came to their initial meeting with several ideas about the script, dance numbers, and hopes to co-direct. As the film moved from development into the pre-production phase, Freed secured MGM talents on Kelly’s recommendation, including Donald O’Connor, a former vaudeville star; Cyd Charisse, a famous ballet star and MGM dancer; and Debbie Reynolds, a 19-year-old up-and-comer whom the studio wanted to develop into a star. And while Freed originally conceived Singin’ in the Rain as another MGM spectacle featuring the songs he co-wrote with Brown, the film’s trajectory changed when Kelly was hired.

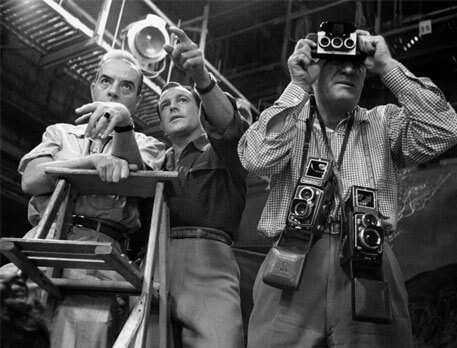

Kelly and Donen would once again work together as co-directors, just as they had during On the Town. The directorial partnership between them placed Kelly in front of the camera, choreographing and concentrating on performance, while Donen remained behind the camera. Together, they prepared for each sequence, reviewed the dailies, and supervised the editing process, with Kelly’s aesthetic choices guiding many of the decisions. Filming began in June 1951, and by that time the sound recording of the songs was already complete, leaving Kelly and Donen to synchronize the dancing. In his years as a Hollywood performer observing his directors, Kelly learned that movement onscreen depends on the movement of the camera, and viewers of a stage performance saw something different than a film’s audience. On the stage, dancers appeared smaller and had to occupy the entire stage along with their costars, so large movements became more important than acting; on film, the camera could move along with the dancer, and the viewer could better appreciate specific movements onscreen, in particular, the actor’s ability (or inability) to remain in character during the dance. Film allowed Kelly to explore his desire to improve the relationship between the dancing, the characters, and the audience. Donen understood his co-director’s ambitions and became immersed in the visual side of capturing Kelly’s performance on camera, though his choices were often dictated by Kelly.

The dynamics of the Kelly-Donen collaboration remain somewhat mysterious, as the two never discussed their working relationship in detail; although, their remarks about one another provide some insight. Kelly described Donen with words like “assistant” and “aide,” while saying he could never direct alone because “You need somebody that you can trust and that can help you.” Kelly’s description of their partnership seems more appreciative of the collaboration than Donen’s memories. Donen remembered that he lost many of their arguments and disagreements: “Substitute the word ‘fight’ for codirect, then you have it,” he later remarked. Donen also criticized his co-director’s more artful choices in the film, claiming the ballet sequences were “pretentious” and “too long.” From their discussions, Kelly seems to be the visionary and Donen was the “third eye behind the camera,” implementing technical solutions to achieve what Kelly wanted to see onscreen. Whatever their off-screen quarrels, their collaboration, along with the efforts of the entire Freed Unit, produced the idea of “cine-dance,” wherein dancing and filmmaking achieve a rare balance. As Kelly admitted, Donen’s technical expertise was invaluable in capturing dance on film and bringing Kelly’s vision to life.

Indeed, Kelly sought to instill an aesthetic theme into Singin’ in the Rain that would represent the integration of narrative into song and dance, forming cine-dance. The development of the narrative’s importance in the musical film derives largely from Broadway musicals of the early 1940s, most prominently Oklahoma! from 1943, wherein the drama was reflected and supported by the songs and dancing, serving as expressionistic and dramatic devices. Narrative existed as a pretext for singing and dancing in Classical Hollywood musicals; without song and dance, a musical’s story and characters would feel incoherent or even contradictory. But the emergence of behind-the-scenes roles such as Dance Director and Choreographer had emerged in American ballet in the late 1930s as essential to a moving dance performance that aligned with the narrative. Kelly himself had developed tap dancing into a character-driven form associated with comedy into a realm of dramatic expression, using his experience in ballet to deliver a performance that used the rhythm and syncopation of his full body motions, tap shoes on the floor’s surface, and pure acting. But for the film, Kelly insisted that the viewer should be able to follow in unison with the dancer, and thus remain entangled in the narrative. The key to cine-dance was shooting dance in such a way that dance never distracted from the film’s narrative thrust. To do accomplish this, Donen used tracking and crane camera techniques that trail the dancing without the wobbly movements of earlier musicals, allowing Singin’ in the Rain’s dance sequences to contain a rare faithfulness to the narrative for a Hollywood musical, as the songs and dance blend seamlessly with the drama and humor.

Indeed, Kelly sought to instill an aesthetic theme into Singin’ in the Rain that would represent the integration of narrative into song and dance, forming cine-dance. The development of the narrative’s importance in the musical film derives largely from Broadway musicals of the early 1940s, most prominently Oklahoma! from 1943, wherein the drama was reflected and supported by the songs and dancing, serving as expressionistic and dramatic devices. Narrative existed as a pretext for singing and dancing in Classical Hollywood musicals; without song and dance, a musical’s story and characters would feel incoherent or even contradictory. But the emergence of behind-the-scenes roles such as Dance Director and Choreographer had emerged in American ballet in the late 1930s as essential to a moving dance performance that aligned with the narrative. Kelly himself had developed tap dancing into a character-driven form associated with comedy into a realm of dramatic expression, using his experience in ballet to deliver a performance that used the rhythm and syncopation of his full body motions, tap shoes on the floor’s surface, and pure acting. But for the film, Kelly insisted that the viewer should be able to follow in unison with the dancer, and thus remain entangled in the narrative. The key to cine-dance was shooting dance in such a way that dance never distracted from the film’s narrative thrust. To do accomplish this, Donen used tracking and crane camera techniques that trail the dancing without the wobbly movements of earlier musicals, allowing Singin’ in the Rain’s dance sequences to contain a rare faithfulness to the narrative for a Hollywood musical, as the songs and dance blend seamlessly with the drama and humor.

Of course, Singin’ in the Rain is not only about dance and its aesthetic integration with narrative; the story also presents a film-about-film—specifically, about an era that ostensibly ended 24 years earlier. Kelly, having a knowledge of silent film as equally enthusiastic as Comden and Green, worked closely with the writing team and contributed to the film’s references throughout. Kelly later admitted, “Almost everything in Singin’ in the Rain springs from the truth. It’s a conglomeration of bits of movie lore.” For instance, Roscoe Dexter (Douglas Fowley)—the director of Singin’ in the Rain’s film-within-the-film—was based on Busby Berkeley; Freed inspired the film’s studio head R.F. Simpson (Millard Mitchell); and Donald O’Connor’s on-set pianist character, Cosmo Brown, came from Freed’s days as a silent film piano accompanist. To ensure the scenes of 1920s-era filmmaking looked accurate, the production required research, more than any other musical by MGM at the time. Kelly insisted on authenticity and requested that production designer Randall Duell and set director Jacque Mapes study archival behind-the-scenes footage around MGM to recreate the look of a 1920s studio lot. The technical crew took the need for authenticity one step further and used actual equipment still lingering around the studio from the silent era as props. From the film’s props to the script, and the implementation of cine-dance, Kelly shaped the production of Singin’ in the Rain to his vision. Production wrapped in November 1951, and preview screenings were already arranged for the following month.

The story has been called a “Fairy-Tale Musical” and compared to Hans Christian Anderson’s The Little Mermaid, but set on the fictional Hollywood soundstage of Monumental Pictures upon the advent of sound. Early on, one character reads a headline on the cover of Variety, calling The Jazz Singer “an all-time hit in the first week,” but another character chimes in, “all-time flop in the second.” Industry fads were common at this time, appearing and disappearing; the film industry itself was considered a fad, bound to disappear. Singin’ in the Rain follows two silent film stars, Don Lockwood (Kelly) and Lina Lamont (Jean Hagen), as they adjust to talkies, which threaten to render their careers obsolete. Don has the looks of Douglas Fairbanks and trained in singing and dancing as a vaudeville star. Lina has not been so fortunate; she has star appeal, but neither the voice nor diction—nor raw talent or smarts—to make it in talkies. (When the studio voices its concerns, Lina replies, “What do they think I am, dumb or something? Why, I make more money than Calvin Coolidge put together!”) As the studio experiments with turning their latest Lockwood-Lamont production, a French costume romance called The Duelling Cavalier, into a talkie, they realize Lina’s harsh, jarring voice will surely irritate audiences. What is more, their technicians are not prepared for audio. A wireless microphone placed on Lina picks up her heartbeat, and her grating voice comes through intermittently when they place the mic in a nearby plant. The adjustment is tiresome, as Lina shouts, “I can’t make love to a bush!”

After a disastrous audience prevue of The Duelling Cavalier with sound, Don feels his career in pictures has come to an end. Meanwhile, his continued flirtation with young ingénue Kathy Selden (Debbie Reynolds) proves fruitful. Along with Cosmo, Don and Kathy conceive the idea to turn The Duelling Cavalier into a musical called The Dancing Cavalier. Given Don and Cosmo’s song and dance origins, and their idea to replace Lina’s voice with Kathy’s, the new film promises to be an instant success. They reshoot the period scenes to reflect the new musical direction, while Don designs several elaborate, modern dance sequences within the bookends of the original period piece. But after learning Kathy will dub over her voice, Lina grows jealous and blackmails Simpson to keep Kathy working, uncredited, as her voice. Simpson is forced to agree, despite Don’s objections, rather than proceed as planned to make a star out of Kathy. At the rousing premiere of The Dancing Cavalier, the audience clamors to hear more singing from its stars, specifically Lina. With a scheme in mind, Don tells Kathy to hide behind the curtain and sing for Lina, who will lip synch. All at once during the performance, the curtain raises and Lina, her deception revealed, becomes a laughing stock. Kathy runs off, but Don announces, “Ladies and gentlemen… That’s the girl whose voice you heard and loved tonight. She’s the real star of the picture. Kathy Selden!” Kathy becomes a star, establishing the new Lockwood-Selden brand, and their genuine romance.

After a disastrous audience prevue of The Duelling Cavalier with sound, Don feels his career in pictures has come to an end. Meanwhile, his continued flirtation with young ingénue Kathy Selden (Debbie Reynolds) proves fruitful. Along with Cosmo, Don and Kathy conceive the idea to turn The Duelling Cavalier into a musical called The Dancing Cavalier. Given Don and Cosmo’s song and dance origins, and their idea to replace Lina’s voice with Kathy’s, the new film promises to be an instant success. They reshoot the period scenes to reflect the new musical direction, while Don designs several elaborate, modern dance sequences within the bookends of the original period piece. But after learning Kathy will dub over her voice, Lina grows jealous and blackmails Simpson to keep Kathy working, uncredited, as her voice. Simpson is forced to agree, despite Don’s objections, rather than proceed as planned to make a star out of Kathy. At the rousing premiere of The Dancing Cavalier, the audience clamors to hear more singing from its stars, specifically Lina. With a scheme in mind, Don tells Kathy to hide behind the curtain and sing for Lina, who will lip synch. All at once during the performance, the curtain raises and Lina, her deception revealed, becomes a laughing stock. Kathy runs off, but Don announces, “Ladies and gentlemen… That’s the girl whose voice you heard and loved tonight. She’s the real star of the picture. Kathy Selden!” Kathy becomes a star, establishing the new Lockwood-Selden brand, and their genuine romance.

Although Singin’ in the Rain would later be called the finest musical ever made, no such claims were made upon its release in late March of 1952. The film cost more than $2.5 million to make and, during its initial release, it earned over $7.6 million in box-office receipts. Many critics of the era, such as Bosley Crowther of the New York Times and Irene Thirer of the New York Post, praised the film’s cheerfulness but felt its audience was limited due to its placement in the 1920s; other critics concentrated on the entertainment value of the film, such as Arthur Knight, who called the film “everything you could ask of a musical.” The majority of reviews highlighted the film’s musical qualities, suggesting it was a particularly great studio effort. But few critics discussed its commentary on the film industry, took substantive note of the film’s cine-dance, or declared it one of the best of its kind. Surprisingly, the film was nominated for just two Academy Awards at the 1953 ceremony, including Best Supporting Actress for Hagen and Best Music. Donen, Comden, and Green told the press they felt “ignored” by the Academy. Instead, at the time of its release in theaters, Academy voters at the March 1952 Academy Awards ceremony remembered Kelly’s film from the previous year, An American in Paris, and garnered it with six Oscars, including Best Picture. Also in 1952, Kelly was awarded an honorary statue for his “versatility as an actor, singer, director and dancer, and specifically for his brilliant achievements in the art of choreography on film.”

Even though Singin’ in the Rain performed well at the box office and received positive reviews, for Kelly, its release was bittersweet. Shortly after production wrapped in November 1951, the actor left Hollywood and the country for a year and a half, claiming he wanted to take advantage of a new tax law that exempted U.S. citizens from paying income tax if they lived abroad for eighteen months. However, since arriving in Hollywood, Kelly had become politically active with the left, and the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) had been carrying out anti-leftist probes of Hollywood, which led to the blacklists and a number of celebrity informants. Kelly, his wife Betsy Blair, Comden and Green, along with others from the production of Singin’ in the Rain had socialist interests, or at least sympathies. Kelly resolved to avoid the HUAC hearings altogether and lived in France for six months, followed by a year in London. When he returned, he did so only because he had convinced Roy Brewer, a right-wing union boss in Hollywood, that he was not a communist. After making two underwhelming films overseas, he resumed his streak of winning musicals with Brigadoon (1954). But Kelly’s later work would not contain the same narrative integrity between the story and dance sequences as Singin’ in the Rain.

Reevaluations of Singin’ in the Rain began in the 1960s, with the film’s emergence at international film festivals, critical reappraisals by figures such as Pauline Kael (who called it “the most enjoyable of all American musicals”), and reconsideration through the auteur theory. The film also made a sudden appearance on Sight and Sound’s decennial critics poll in 1962—chosen by a single critic. Over the years, more critics included the film on the British Film Institute’s seminal list, and it retains a place there as recently as the 2012 edition, where it received 46 votes. Moreover, the American Film Institute includes the film six times on its various “100 Years…” lists, including the number one spot on its list of greatest musicals. In more serious assessments, the film’s co-authorship of Kelly and Donen poses a troublesome problem for scholars when viewing it through an auteurist lens. Typically, films from the classical era of Hollywood are resistant to auteurist interpretations due to the studio system’s enforced standards and collaborative productions. Nevertheless, certain elements of the film undoubtedly attracted critics and scholars to re-examine it beyond the sheer sparkle and cheerfulness it exudes. Later analyses were guided by, first, the self-reflexive look at filmmaking, and second, Kelly’s implementation of cine-dance.

Reevaluations of Singin’ in the Rain began in the 1960s, with the film’s emergence at international film festivals, critical reappraisals by figures such as Pauline Kael (who called it “the most enjoyable of all American musicals”), and reconsideration through the auteur theory. The film also made a sudden appearance on Sight and Sound’s decennial critics poll in 1962—chosen by a single critic. Over the years, more critics included the film on the British Film Institute’s seminal list, and it retains a place there as recently as the 2012 edition, where it received 46 votes. Moreover, the American Film Institute includes the film six times on its various “100 Years…” lists, including the number one spot on its list of greatest musicals. In more serious assessments, the film’s co-authorship of Kelly and Donen poses a troublesome problem for scholars when viewing it through an auteurist lens. Typically, films from the classical era of Hollywood are resistant to auteurist interpretations due to the studio system’s enforced standards and collaborative productions. Nevertheless, certain elements of the film undoubtedly attracted critics and scholars to re-examine it beyond the sheer sparkle and cheerfulness it exudes. Later analyses were guided by, first, the self-reflexive look at filmmaking, and second, Kelly’s implementation of cine-dance.

Amid the fifteen songs featured in the film, most of them contain dance sequences, each mixing with the narrative through cine-dance, as Kelly envisioned, and none more so than the “Singin’ in the Rain” number. Representative of the film’s integration of lyrics, music, and dance as having a place in the story, the sequence is deceptively simple. But upon examination, it proves quite complex, as it appropriates, integrates, and literalizes a well-known song from previous decades into the narrative. At first look, Kelly’s dance in the rain appears like nothing more than a soundstage piece, a standard “putting on a show” number that exists primarily for its entertainment value. But the sequence must come at the precise moment in the story in which the happiness of Kelly’s character overrides all else, and singing in the rain is an appropriate action not forced into the narrative. Don, Kathy, and Cosmo have just thought to make The Duelling Cavalier into a musical, and after walking Kathy home in the rain, Don realizes his career and romantic troubles seem to be over. It resembles a sequence in Cover Girl, in which Kelly, Rita Hayworth, and Phil Silvers dance out of a restaurant and into the street, singing, dancing on the sidewalk, and annoying a policeman in the process. Similarly, Kelly leaves Kathy and begins to sing and dance in the rain. He feels the downpour on his face, catches it in his mouth, and squirts it back out; he twirls his open umbrella; he dances up and down stoops and porches; he swings from light posts; and, finally, he splashes about like a child in a puddle, much to the suspicion of a disapproving policeman. The scene would have seemed nonsensical anywhere else in the story, but instead, it feels like an expression of joy at the only appropriate moment in the film.

Although Kelly wanted to unify narrative with song and dance in Singin’ in the Rain, he also wanted the film to be a “Broadway Melody” of sorts, presenting a showcase for a wide range of dancing and musical styles, including the French Cancan, burlesque performance, vaudeville, Ziegfeld Follies, and ballroom dancing. The Freed-Brown duo had written most of the songs back in the 1920s and 1930s, but they were adapted into 1950s styles, in part to sound pleasant to contemporary ears, in part to facilitate particular dances. For example, Kelly dug into the Freed-Brown catalogue of songs to find “Make ‘em Laugh,” knowing O’Connor’s background in vaudeville. Starting with the song, Kelly and O’Connor developed the sequence where Cosmo delivers a small compilation of physical gags and slapstick in unison with song and dance. The scene, shot mostly in long takes, shows O’Connor dancing with a dummy, bouncing his head on a plank of wood, leaping through drywall, and performing backflips. Only one song was written for the film, the “Moses Supposes” number that allows Kelly and O’Connor to engage in wordsmithing and dance in a hilariously irreverent, absurdist performance that also provides a commentary on Hollywood’s diction coaches.

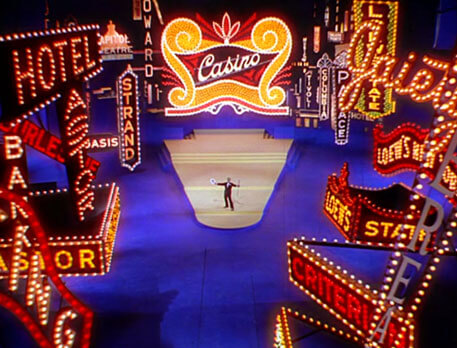

Just as Kelly wanted Singin’ in the Rain to be a “Broadway Melody” showcase of dancing styles, Kelly insisted that his character be a reflection of himself, and so Don has the same ambitions for The Dancing Cavalier. This meant the dance numbers in Singin’ in the Rain exist in the film’s reality, whereas many Classic Hollywood musicals used dream sequences to explain away spectacles such as the “Singin’ in the Rain” sequence. Even the film’s most expressive dance, the lengthy Broadway Ballet, exists in a practical context. Running more than eight minutes long, the Broadway Ballet sequence transitions through several types of dance, ballet most prominently, in a series of stagey nightclub and casino sets. Ballet had become popular on Broadway following the stage hit On Your Toes in 1936, and most stage musicals in the next decade or more would feature at least one ballet number, many of them based on surreal dream sequences. Surrealism was prevalent in 1940s Hollywood with the popularization of Freudian psychoanalytic dream analysis, demonstrated in the Salvador Dali-designed dream sequence in Alfred Hitchcock’s thriller Spellbound (1945) or the twisted ballet in the Astaire romance Yolanda and the Thief (1945). And while Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s films The Red Shoes (1949) and The Tales of Hoffman (1951) had already demonstrated how artful—and commercially successful—the amalgamation of surreal ballet and cinema could be, Kelly’s painterly ballet sequence in An American in Paris proved much the same. Without these earlier examples of ballet in film, it is doubtful Kelly would have been allowed to indulge in the film’s extended sequence.

Singin’ in the Rain’s story fades into the Broadway Ballet sequence not as a dream sequence or hallucinatory aside, but as the visualization of a dance number for The Dancing Cavalier that Don proposes to Simpson. Don explains to Simpson that the sequence begins as the hero of The Dancing Cavalier, a Broadway performer, reads backstage until being struck in the head with a sandbag. The character, played by Don, wakes during the French Revolution and dances his way through several historical modes, leading to his presence in a modern club for gangsters, where he pursues a mobster’s beautiful inamorata, played by Charisse. They eventually meet in a wistful, dreamlike scarf ballet, moving among the coils of a fifty-foot piece of Chinese silk. The dance is not surreal within the context of the narrative; rather, it is a visualized description of the dream-within-the-film-within-the-film, and therefore a practical matter. Its placement enhances the narrative rather than disrupt it or provide an interlude. More than any other dance number in the film, the Broadway Ballet sequence seems to epitomize Kelly as the dancer-performer and further legitimize ballet as a commercially appealing artform, as he has so carefully integrated it with the film’s narrative through cine-dance.

The dreamy, if grounded dance sequences in Singin’ in the Rain underscore its prevalent theme that considers the difference between Hollywood artifice and reality. When integrating sound into The Duelling Cavalier, Dexter hilariously struggles to show Lina how to deliver her lines into the microphones. After tense reshoots to include sound, preview crowds boo the first cut, as Don’s larger-than-life acting style, Lina’s chirping voice, and the production’s booming use of sound altogether change the function of their silent film script. The dialogue written for their silent film’s intertitles sounds awkward when spoken, so it must be rewritten. Moreover, their voice performances must be calibrated for film to avoid sounding mannerist. To solve the problem, they rely on looping, the practice of dubbing over dialogue in post-production. As looping puts new sounds to the original images, Singin’ in the Rain demonstrates the ways in which films represent illusions, and that what the viewer sees is not always real.

After making their audience aware of the artifice at work in a Hollywood production, Kelly and Donen ensure that any cognizance of Hollywood’s cinematic apparatus does not diminish their own film’s effectiveness. By hiding their film’s artifice through cine-dance, the filmmakers can engage their audience on an emotional level and still provide a commentary on Hollywood filmmaking. Their approach is best reflected by comparing the “You Were Meant For Me” sequence to its counterpart, the scarf dance that occurs later in the film at the end of the Broadway Ballet. Consider how, earlier in the film, Don exposes Kathy to the magic of a film’s soundstage as he sings “You Were Meant For Me.” On an empty Monumental Pictures soundstage, Don switches on romantic lighting, turns on a fan for a slight breeze, stands before a matte painting of a sunset, and sings to Kathy, openly acknowledging the artificiality of the ambiance around them. The “You Were Meant For Me” sequence is mirrored by similar soundstage atmospherics to create a romantic mood in the scarf dance between Kelly and Charisse, although the visible apparatuses have been hidden. Note how the spotlights in the “You Were Meant For Me” sequence remain stationary, suggesting the unattended production equipment, whereas, during the latter scarf dance, the lights follow Kelly and Charisse about their dreamstage. And yet, the audience is no less taken by either performance, even though the film, earlier, made the viewer aware of the cinematic apparatus creating this mood.

Due to the technical divide between sound and image in filmmaking, musicals, more than any other film genre, contain a “fundamental dishonesty” that Kelly wanted to point out and correct within Singin’ in the Rain’s themes and cine-dance. The film’s themes underscore how sound and image function together in cinema, producing an outcome that audiences will either accept or rebuke depending on how well they align. In the earliest scenes set in 1927, Don tells his brief life story to a reporter at a ritzy premiere, and his voiceover about a dignified and privileged upbringing contrasts the flashback’s image: Don and Cosmo getting their start in shoddy piano halls and vaudeville acts. Later, during the production of The Dancing Cavalier, the film reveals how filmmaking is mechanical trickery—disjointed sound and images assembled by technicians. As Kathy loops her voice over Lina’s, the recording does not match up at first and looks strange; but a moment later, as the technicians synchronize sound and image, Kathy’s voice seems to come from Lina’s mouth.

Due to the technical divide between sound and image in filmmaking, musicals, more than any other film genre, contain a “fundamental dishonesty” that Kelly wanted to point out and correct within Singin’ in the Rain’s themes and cine-dance. The film’s themes underscore how sound and image function together in cinema, producing an outcome that audiences will either accept or rebuke depending on how well they align. In the earliest scenes set in 1927, Don tells his brief life story to a reporter at a ritzy premiere, and his voiceover about a dignified and privileged upbringing contrasts the flashback’s image: Don and Cosmo getting their start in shoddy piano halls and vaudeville acts. Later, during the production of The Dancing Cavalier, the film reveals how filmmaking is mechanical trickery—disjointed sound and images assembled by technicians. As Kathy loops her voice over Lina’s, the recording does not match up at first and looks strange; but a moment later, as the technicians synchronize sound and image, Kathy’s voice seems to come from Lina’s mouth.

Indeed, the disparity between sound and image, and their correct attribution to their respective performers, presents a thematic anxiety in both the narrative and the filmmaking in Singin’ in the Rain. Lina’s appearance in The Dancing Cavalier and her false voice credit present a disparity between the visual and aural, and Don yearns to secure Kathy her due credit. Only after sound and image perform in harmony again, during the climactic scene where Kathy is revealed to the premiere crowd to be Lina’s voice, does order feel restored. Of course, Kelly insisted on long takes and minimal reliance on montage to assemble the film’s dance numbers, ensuring there would be no question of unity between sound and image in relation to his dancing. Kelly’s ambitions for the film seem to align with Don’s for The Dancing Cavalier, as both talents hope to create a film that, due to their technical seamlessness, the audience will watch on an emotional level and forget about the filmmaking. Likewise, Singin’ in the Rain’s illusion is so complete that the viewer never questions or suspects the authenticity behind Kelly, Reynolds, or O’Connor’s voice talents in conjunction with their image (although, like most musicals of the time, the audio track for the songs was recorded before shooting and added in post-production).

Singin’ in the Rain establishes a theme that juxtaposes the real and unreal, reality and cinematic fantasy, and the illusory unity of sound and image through the film’s dominant metaphor: unwavering happiness and optimism, regardless of the rain. The film’s representation of Hollywood’s illusions offers a self-aware commentary filled with humor and clever wit about the film industry, its technical practices, and the uglier side of celebrity. While the imitation and parodying of the sound era comes from Comden and Green, who were film enthusiasts and had often written comic sketches parodying the film industry, they, like Kelly, had a genuine affection and passion for cinema. But even as the film exposes the artifice of cinema and how its magic depends on the illusions created by technicians, it embraces the end product, celebrating films and filmmakers regardless of their manipulations. That audiences can watch, laugh, fall in love, and escape for two hours without being distracted by what they know (or learned from the film) about the filmmaking process, represents a rare accomplishment. But the dramatic and technical themes in Singin’ in the Rain echo Kelly’s insistence on the narrative’s unity with song and dance, and his desire to improve how filmmaking realizes that unity.

Critical and scholarly reassessment of Singin’ in the Rain after its release formed around Kelly, who sought to make a film for commercial audiences, yet incorporate artistic forms of dance within the accessible narrative. In essence, he wanted everyone to love ballet and tap as much as he did; and ultimately, his film would contain an infectious fascination with those forms of dance. Kelly sought to shape the film around his cherished visual form of expression, and in order to do so, he had to learn how to shoot dancing in a way that supported the performers onscreen, as well as use dancing as a storyteller’s device. His ambitions were more about elevating dance than exploring filmmaking, and his desire to bring tap and ballet to a wider audience impelled his choices to become a studio choreographer and eventual co-director. The lasting effect of Singin’ in the Rain is not only that it remains a joyous and entertaining film, but that it also happens to be an uncommon work of complex, often meta-styled art. Kelly’s ability to merge dance, an artform typically associated with high art, with cinema, an artform associated with popular or mass art, was his rare vision and achievement, albeit supported by a cast and crew of MGM’s finest contracted talent.

Critical and scholarly reassessment of Singin’ in the Rain after its release formed around Kelly, who sought to make a film for commercial audiences, yet incorporate artistic forms of dance within the accessible narrative. In essence, he wanted everyone to love ballet and tap as much as he did; and ultimately, his film would contain an infectious fascination with those forms of dance. Kelly sought to shape the film around his cherished visual form of expression, and in order to do so, he had to learn how to shoot dancing in a way that supported the performers onscreen, as well as use dancing as a storyteller’s device. His ambitions were more about elevating dance than exploring filmmaking, and his desire to bring tap and ballet to a wider audience impelled his choices to become a studio choreographer and eventual co-director. The lasting effect of Singin’ in the Rain is not only that it remains a joyous and entertaining film, but that it also happens to be an uncommon work of complex, often meta-styled art. Kelly’s ability to merge dance, an artform typically associated with high art, with cinema, an artform associated with popular or mass art, was his rare vision and achievement, albeit supported by a cast and crew of MGM’s finest contracted talent.

Long before his arrival in Hollywood, Kelly aspired to blend dance with narrative and, with the technical assistance of Donen to realize his vision, he finally achieved his goal with Singin’ in the Rain. But the collaboration and shared credit between co-directors, along with its status as a product of the Classic Hollywood era, have long challenged film scholars to identify whether Singin’ in the Rain has an author, despite its legacy. However, the film remains too distinct from other musicals to be described as a typical MGM programmer. Singin’ in the Rain represents a unique synthesis of narrative and dance based on Kelly’s desire to unify them into an original storytelling expression. As we have seen, the film adopts the formal precision of a Golden Age musical, but Donen’s technical efforts were shaped and tested by Kelly’s ambition to integrate dance and narrative into cine-dance, thus extending the production beyond the requirements of an average MGM release. Indeed, Kelly’s influence over the production informs nearly every element of the film, the themes, narrative structure, and Donen’s technical choices above all. Using Classic Hollywood’s collaborative studio system to meet his needs as a dancer, storyteller, and filmmaker, Kelly succeeded in achieving his singular vision.

Bibliography:

Behlmer, Rudy. America’s Favorite Movies: Behind the Scenes. Samuel French, 1990.

Brideson, Cynthia and Sara Brideson. He’s Got Rhythm: The Life and Career of Gene Kelly. The University Press of Kentucky, 2017.

Cohan, Steven. “Case Study: Interpreting Singinʼ in the Rain.” Reinventing Film Studies. Ed. Christine Gledhill and Linda Williams. Oxford UP, 2001, pp. 53–75.

Ewing, Marilyn M. “Dance! Structure, Corruption, and Syphilis in Singin’ in the Rain.” Journal of Popular Film & Television, vol. 34, no. 1, Spring 2006, pp. 12-23.

Hess, Earl J. and Pratibha A. Dabholkar. Singin’ in the Rain: The Making of an American Masterpiece. University Press of Kansas, 2009.

Juddery, Mark. “Breaking the Sound Barrier.” History Today, vol. 60, no. 3, Mar. 2010, pp. 37-43.

Silverman, Stephen M. Dancing on the Ceiling: Stanley Donen and His Movies. Alfred A. Knopf, 1996.

Wollen, Peter. Singin’ in the Rain. BFI Film Classics. Palgrave MacMillian, 2012.

Yudkoff, Alvin. Gene Kelly: A Life of Dance and Dreams. Back Stage/Watson-Guptill, 1999.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review