The Definitives

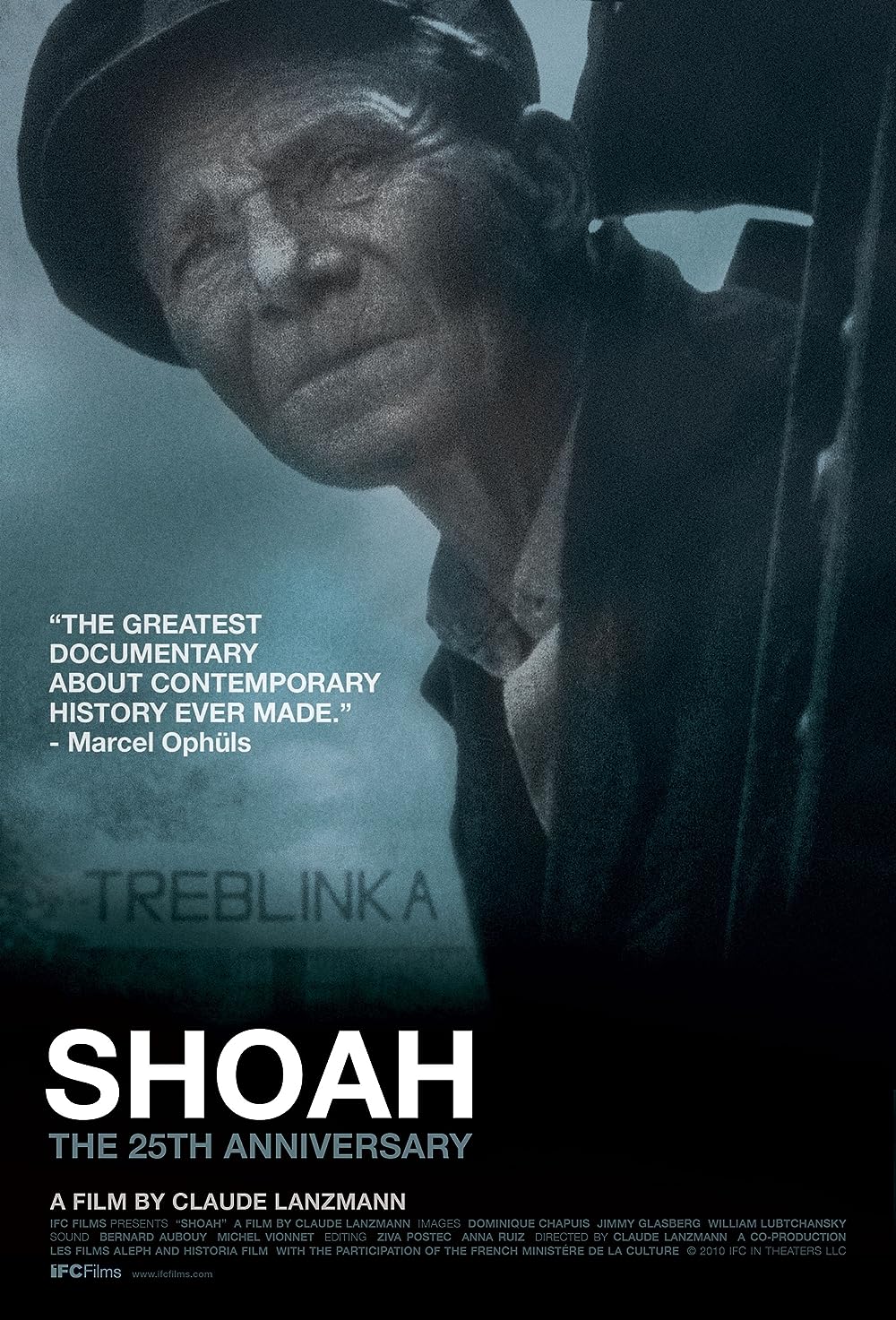

Shoah

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Polish lawmakers sought to pass a bill in 2018 that would make it a criminal offense to suggest the country’s complicity in the crimes committed by Nazi Germany in the Second World War. This included using the term “Polish death camps” when referring to Auschwitz, Chełmno, Sobibór, Treblinka, and other concentration camps located in Nazi-occupied Poland. The bill sought to “defend the good name of Poland,” stomping out any suggestion that Poland was somehow responsible for the mass extermination of Jews and other groups during the Holocaust. Representatives from Israel claimed that Poland’s right-wing Law and Justice party behind the bill was seeking to “challenge historical truth.” Not long after the party introduced the bill, widespread objections and political backlash led to the Polish government dialing back the proposed level of punishment to a civil offense. But after its attempt to deny or rewrite both responsibility and history, one cannot help but consider what prompted the attempt. The legislation was introduced in part to clarify that, under Nazi rule, the concentration camps were technically not Polish, and therefore the term “Polish death camps” inaccurately describes them. But the measure was perceived by many throughout the world as an attempt by the Polish government to deny the role of Polish citizens in several pogroms carried out not only by Nazis, but also by Poles who willfully ignored what was happening to their Jewish neighbors, or even worse, Poles who themselves carried out the murder of Jews.

Holocaust historians have long maintained the consensus that some Polish citizens, sometimes entire villages, collaborated with the Nazis to help exterminate the three million Polish Jews murdered in the Holocaust. As historian Jan T. Gross, author of Fear: Anti-Semitism in Poland After Auschwitz, unequivocally states in his 2001 book Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland, about the murder of more than 1,600 Polish Jews by their non-Jewish neighbors: “It is simply not true that Jews were murdered in Poland during the war solely by the Germans.” The question of Polish complicity lies under the surface of Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah, and the sections of it that uncover a lingering Polish anti-Semitism and resentment of the Jew. If Lanzmann’s nine-and-a-half-hour film is not directly about the involvement of Poland’s non-Jewish citizens in the Holocaust, then its form and themes return the past to the present day, providing a link between then and now, and feel achingly ripe for reconsideration in the wake of Poland’s attempted Holocaust bill, or any future efforts by a government or institution that would try to distance themselves from their past. The purpose of this essay is not to issue a sweeping condemnation of the Polish or associate the crimes of a few individuals with the country at large, but rather to use the Polish anti-defamation bill as a launching pad to revisit Shoah as a method of reliving the past. The film delivers the past into an urgent experience of the present, making it impossible to move onward and place the Holocaust into the space of an uncomfortable distant memory—which is where some would install it if laws that inhibit open communication about the Holocaust are allowed to persist.

Released in 1985, Shoah is the culmination of thirteen years of both capturing interviews and editing them into a film unlike any other in history. In this work constructed almost entirely of voiceover, talking head interviews, and images of actual locations—and a notable absence of historical footage—Lanzmann recreates the past through a subtle, dialectical editing style and aching witness testimony. Among the many Holocaust survivors, perpetrators, and witnesses, Lanzmann interviews several Poles who were around during the Nazi occupation. The interviews reveal that some of the remaining Polish population still differentiates Poles from Jews, even though both groups were Polish citizens. We hear remarks ringing with an anti-Semitic tone about the Jews who controlled this or that village because they were the richest. The Polish women interviewed seem to still resent Jewish women for their beauty, which they claim is on account of their lazy lifestyle, afforded because they were rich. The Jews stank, according to one Pole, because they were tanners. And a crowd gathers outside of a Catholic church at one point, where witnesses suggest the Jews died in the Holocaust as retribution for killing Christ. In other, more subtle ways, the lingering anti-Semitism is evident as Treblinka resident Czeslaw Borowi imitates Yiddish with a mocking tone, “La-la-la.”

During the six years he took to shoot interviews, Lanzmann conducted several in the Polish villages around former concentration camps. He finds an atmosphere that is mournful at times but more often indifferent. Many of his Polish subjects, interviewed thirty years after the Holocaust, deny knowing what exactly was happening around their community. They knew the Jews were being taken from their villages or delivered by train to camps, but they claim they didn’t know the Nazis were exterminating them. The Polish bystanders who lived near the camps saw countless Jews enter the camps, they could hear screaming, and then describe an unnerving silence around the camps that signaled something was wrong—but what, they could not know, and they voice no apparent need to find out. At this, we cannot help but remember the secretly recorded interview between Lanzmann and a former SS officer, who said the stench of death around the camps was evident for miles. “At first it was unbearable,” says one Polish bystander of the tense atmosphere and absence of the Jews, “then you get used to it.” Note also the account that claims Poles refused to help the Jewish resistance efforts in the Warsaw ghetto. Of course, Lanzmann’s few interviewees do not represent every non-Jewish citizen of Poland, but a pattern emerges even if its intentionality is uncertain.

Before considering further how Shoah underscores the role of Polish non-Jews in the Holocaust, Shoah demands some level of understanding as a work of cinema, since its creation and legacy are instrumental to how Lanzmann considers Polish complicity. The film project was conceived in 1973 by Alouph Hareven, an intelligence officer in Israel’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs who wanted to address the Holocaust from the Jewish perspective and consider the full weight of its atrocity. Lanzmann was hired to make a two-hour documentary, but over time he shot upwards of 350 hours of footage and, after losing his production’s original financiers and struggling to maintain his backers, resolved to complete a much larger project. In some cases, he spent years tracking down reclusive witnesses and former Nazis. Lanzmann’s goal was, as he wrote in an essay about the film, to question not “How was the Holocaust possible?” but “How is it possible, thirty years after the Holocaust, that we should be where we are?” The same question applies today in the wake of Poland’s bill, or information found in a 2018 poll conducted by Claims Conference, an institution devoted to education and research about the Holocaust: The poll finds that nearly half of American millennials cannot name a single concentration camp, while only 41 percent of all Americans could identify Auschwitz. When the lessons of the Holocaust have so often been associated with a message to “never forget,” it seems that, over time, its place in the cultural memory cannot help but fade. But Shoah returns the Holocaust to the present in unflinching detail.

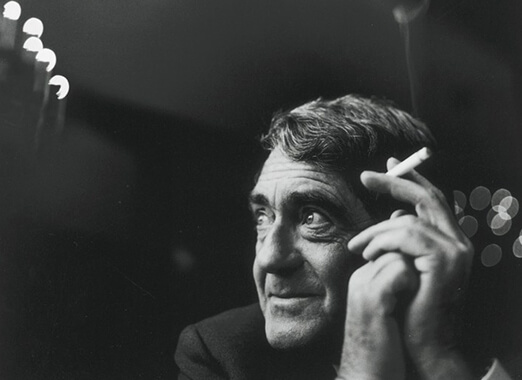

Lanzmann has dedicated his life to Jewish history, primarily that of the twentieth century. His first film, Pourquoi Israel (Why Israel, 1972), spent three hours on the formation of Israel in 1948 and how it changed after 25 years. He returned to the subject of Israel later in his career as well with Tsahal (1994), about the Israeli army, and Lights and Shadows (2008), an interview with Israel’s former Prime Minister Ehud Barak. Yet, the Holocaust has remained Lanzmann’s most explored subject. He made several other documentaries from the cut footage assembled during the production of Shoah, including A Visitor from the Living (1999) and The Karski Report (2010). But Lanzmann was not always a filmmaker. As detailed in his 2012 memoir The Patagonian Hare, he was born in France in 1925 to Jewish parents with Eastern European backgrounds, and early in his life, he experienced racial discrimination that has emboldened his Jewish identity. To this day, he has balanced action and philosophy. He fought the Nazis with the French resistance during the latter part of the World War II, and he followed his efforts as a freedom fighter with years of philosophical study and teaching in Tübingen, and later Berlin. His series of articles in Le Monde starting in 1952 drew the attention of Jean-Paul Sartre, Lanzmann’s eventual mentor and collaborator on the journal Les Temps Modernes, for which Lanzmann was the chief editor until just recently. His persona as thinking a man’s man of action is evident onscreen in Shoah, from his willingness to push witnesses for the delicate details or put himself in danger by secretly filming former Nazis.

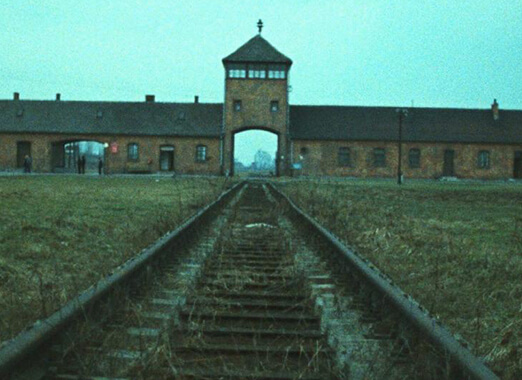

The form and protracted length of Shoah reveal much about Lanzmann’s intentions with the film. Over more than nine hours, Lanzman presents 16mm footage without a musical score or traditional chronological structure. It proceeds in two halves, the first about the road to the gas chambers, the second inside of the gas chambers and ghetto. It does not mythologize or present cold academic exposition about the Holocaust. We hear the voices of others, translated by a series of interpreters who seemingly always smoke cigarettes. The film offers long shots along the actual rail line or dirt roads that led to the Nazi extermination camps, as these pathways carry the viewer from the early sections about Poland and the gas vans to the later segments about the gas chambers and the Warsaw ghetto. Other, immersive passages scan the landscape, gazing at fields where these crimes against humanity were once committed. The camera looks out from high above a forest, examining the extensive woods where so many Jews were buried after they were gassed inside a mobile van unit. As Lanzmann considers the ordinariness of the modern setting, the voices of his interviewees cannot be ignored. Survivors describe situations of mass murder, while bystanders explain what they saw. It all happened in the real world before us, Lanzmann seems to say, not in some horrible nightmare. It took place in fields and forests and along backroads not unlike ones that might be around where you live. And the sheer amount of time we spend with the film is a step toward appreciating what happened; toward understanding what those who died in the ghetto, gas vans, and concentration camps endured; and toward grasping the interplay of ideological perspectives.

The form and protracted length of Shoah reveal much about Lanzmann’s intentions with the film. Over more than nine hours, Lanzman presents 16mm footage without a musical score or traditional chronological structure. It proceeds in two halves, the first about the road to the gas chambers, the second inside of the gas chambers and ghetto. It does not mythologize or present cold academic exposition about the Holocaust. We hear the voices of others, translated by a series of interpreters who seemingly always smoke cigarettes. The film offers long shots along the actual rail line or dirt roads that led to the Nazi extermination camps, as these pathways carry the viewer from the early sections about Poland and the gas vans to the later segments about the gas chambers and the Warsaw ghetto. Other, immersive passages scan the landscape, gazing at fields where these crimes against humanity were once committed. The camera looks out from high above a forest, examining the extensive woods where so many Jews were buried after they were gassed inside a mobile van unit. As Lanzmann considers the ordinariness of the modern setting, the voices of his interviewees cannot be ignored. Survivors describe situations of mass murder, while bystanders explain what they saw. It all happened in the real world before us, Lanzmann seems to say, not in some horrible nightmare. It took place in fields and forests and along backroads not unlike ones that might be around where you live. And the sheer amount of time we spend with the film is a step toward appreciating what happened; toward understanding what those who died in the ghetto, gas vans, and concentration camps endured; and toward grasping the interplay of ideological perspectives.

Shoah does not attempt to encapsulate all information about the Holocaust, but it brings a small piece of it to life. As Sue Vice observes in her BFI monograph, “The film would itself constitute a piece of reality and not be simply a reflection of it.” Interviewee Raul Hilberg, a history professor, and the sole non-witness in the film, gives some insight into his approach to studying the Holocaust: “I never began with the big questions because I feared inadequate answers.” Lanzmann seems to follow this philosophy toward history as well. He resists summarizing or compressing every aspect of the Holocaust into the documentary format. Rather, he focuses predominantly on Poland and the Jewish victims, avoiding any significant discussion of the other groups targeted by the Nazis. He doesn’t concern himself with the Second World War or its many shifts in power. Nor does he show much interest in exploring directly the Nazi ideology that resulted in what Hitler’s Third Reich called the mass “evacuation” of the Jews. Addressing the subject matter with more depth than breadth, he cuts into the industrialized process of death and reveals how it was able to be carried out.

Structurally, the film leaps from story to story, anecdote to anecdote, yet it never loses us or becomes ungainly because of the vitality of its subject, despite the nonlinear and almost poetic exchange of images and interview subjects. Shoah opens with and returns to Simon Srebnik, who was executed at Chełmno at the age of 15 but survived because the bullet somehow “missed his vital brain centres” according to the film’s opening titles. In the film’s first scenes, Srebnik returns to the Narew River where SS officers once made him sing. He walks along the road to the Chełmno concentration camp, now an empty field, and you can see the memories process in his eyes. “This is the place,” he says. Other scenes unfold like a spy-thriller, complete with a surveillance van outside of the hotel where Lanzmann meets former SS officer Franz Suchomel. Lanzmann somehow convinces Suchomel, and others in similar conditions of hiding or anonymity, to give interviews while a hidden camera and microphone record their statements, and two technicians outside in a surveillance van ensure the recording goes smoothly. This sequence involving Suchomel may raise ethics of informed journalistic consent, as Lanzmann tells the former Nazi onscreen that he will remain anonymous; then again, any discussion about informed consent is frequently overlooked in this context given that Suchomel aided in the killing of hundreds of thousands at Treblinka and served a mere six years for his crimes. Amid the many interviews and footage of contemporary locations, Lanzmann addresses the camera directly only once to read a letter penned by a doomed rabbi from Grabow, a town a few miles away from Chełmno.

Although on the surface Shoah may seem to be a staid visual experience, cross-cutting between the mostly stationary witnesses and the present-day lands where the events that they describe took place, the visuals are nonetheless essential and urgently cinematic. Lanzmann engages in dialectical montage, the integral component of Soviet montage theory at its most basic, wherein the conflict between images produces an intellectual understanding and emotional response. Lanzmann and his editor Ziva Postec cut sections together not in a linear progression but a philosophical and thematic one. By placing scene-of-the-crime images from the present-day against the testimony of those who were there between 1941 and 1943, the period covered by the film, Lanzmann forces the viewer to consider the difference between the past, visualized in our imagination based on the witness accounts, and the now shown before us. Watch carefully the dialectical associations created when Shoah presents several Polish witness accounts cut together within a short span. Each Polish witness describes the throat-cutting gesture they claim to have used to warn Jews of their fate, and given the proximity of these gestures alongside the testimony, the gesture and its intention begin to feel ominous—more like a promise than a warning.

Although on the surface Shoah may seem to be a staid visual experience, cross-cutting between the mostly stationary witnesses and the present-day lands where the events that they describe took place, the visuals are nonetheless essential and urgently cinematic. Lanzmann engages in dialectical montage, the integral component of Soviet montage theory at its most basic, wherein the conflict between images produces an intellectual understanding and emotional response. Lanzmann and his editor Ziva Postec cut sections together not in a linear progression but a philosophical and thematic one. By placing scene-of-the-crime images from the present-day against the testimony of those who were there between 1941 and 1943, the period covered by the film, Lanzmann forces the viewer to consider the difference between the past, visualized in our imagination based on the witness accounts, and the now shown before us. Watch carefully the dialectical associations created when Shoah presents several Polish witness accounts cut together within a short span. Each Polish witness describes the throat-cutting gesture they claim to have used to warn Jews of their fate, and given the proximity of these gestures alongside the testimony, the gesture and its intention begin to feel ominous—more like a promise than a warning.

Lanzmann’s subtle aesthetic juxtapositions draw parallels between the past and present, transforming the spectatorship of Shoah into an experience of dialectical understanding. Look at how he films Abraham Bomba, a Jew now relocated to Israel, where he works in a barbershop. Bomba describes in English how he was forced to administer haircuts to women inside of the Treblinka gas chamber, and during his account, he gives a haircut to a non-English-speaking customer seated in the barber’s chair. The viewer cannot help but visualize Bomba in the chamber, in part due to Lanzmann’s insistence on detailed descriptions. Bomba’s voice alone may not have achieved the same response in the viewer, but seeing him cut hair as he talks about his experiences offers a poetic comparison between then and now. Similarly, during stories of the cattle trains transporting Jews to Treblinka, Lanzmann shows us that the rail station is still in use today, carrying travelers for ordinary, run-of-the-mill use. The film also contains many images of the industrial factories along the Ruhr Valley in contemporary Germany, which evoke the industrialization of death organized for the concentration camps. A sequence in which Lanzmann reads from a letter that details the technical improvements requested on gas vans, produced by the vehicle manufacturer Saurer, is placed over the image of a modern-day Saurer van driving along on a highway. As Shoah emphasizes the bureaucratic routines, schedules, paperwork, budgeting, and timetables required to carry out the Holocaust, Lanzmann’s subtle use of dialectic editing underscores that, in the forty years between the Holocaust and his film, industrialization itself never stopped; it merely found other objectives.

As time and space create an expanse between the Holocaust and today, it becomes a myth, and myths can be distorted and reshaped through representation. Shoah combats mythologies and generalities about the Holocaust. It relies on witness testimony to accumulate details about its subject, treating it not as the evilest act ever carried out by one group of people against another, but rather a portrait of the reality of the industrialized genocide conducted by ordinary human beings. It’s an affront to the distanced, safe statement that we will “never forget” this happened. Of course, few could forget the cold facts and figures about the six million Jews, and another eleven million from other targeted groups, succumbing to Nazi mass killings—if they ever learn them. But dramatizations and cathartic stories about the human spirit, ranging from films such as The Diary of Anne Frank (1958) or Judgment at Nuremberg (1961), which affect a sort of “case closed” mentality, make it easier to heal. It’s one thing to read dry facts or see dramatizations of the Holocaust; it’s another thing entirely to hear witness accounts. “Museums and monuments instill forgetfulness as well as remembrance,” titles read in Lanzmann’s 2001 documentary Sobibór, October 14, 1943, 4 p.m., another short documentary made from scenes left out of Shoah, whereas interviews bestow the veracity of “living words.”

In this sense, Shoah is not a traditional or straightforward work of history; it is a use of the cinematic medium to describe the reality of the Holocaust through witness testimonies, the viewer’s imagination, and the director’s visual poetry. It is history in what Lanzmann describes as the “objective spirit,” though he refuses to use archival footage, in part because he believes that showing actual images from the Holocaust can never adequately represent the full extent of the atrocity. It is this reason that Lanzmann has found dramatizations of the Holocaust, most emphatically Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List (1993), to be inadequate, if not deceptive. Indeed, Lanzmann has engaged in aesthetic debates with figures such as Jean-Luc Godard about the filmmaker’s ethical responsibility to show or not show images from the actual Holocaust. Godard has argued that the viewer of Shoah sees nothing of the real Holocaust, and therefore the film cannot adequately represent its real-life horrors as effectively as, say, the 1955 documentary Night and Fog by Alain Resnais, which featured some of the first footage of concentration camps ever screened for the world. Lanzmann’s approach is less didactic, in that he doesn’t show us the Holocaust; and yet, we see it through a series of intellectual and emotional correlations between image, voice, and imagination.

Avoiding hard figures and historical exposition, Lanzmann does not consider Shoah to be a documentary; rather, he uses the term “La fiction du réel,” or the fiction of the real. His film does not capture an event in real time nor use verité techniques to affect a really-there aesthetic; it presents a factual narrative that unfolds in the audience’s imagination as we listen to testimony, observe the ruins of former concentration camps, and watch the behaviors of the witnesses as they give their evidence. His treatment contradicts the general notion that the Holocaust was made possible because a faction of anti-Semites took control of Germany and proceeded to exterminate their scapegoat of choice. Reality as Lanzmann explores it is much more complicated. Shoah reveals a series of social and cultural contexts—an embedded prejudice and willful ignorance that allowed an industry of death to emerge in the first half of the twentieth century. It creates a portrait of the Holocaust’s climate, from the unceremonious use of gas vans to eliminate Jews when mass shootings proved too conspicuous, to those who watched, supposedly unaware and quietly disapproving, yet not compelled to act. Lanzmann refuses to permit the viewer to heal and cover up these wounds of the past. He wants to examine the scar tissue and, in doing so, he exposes that not every wound has healed.

Lanzmann wrote that a worthy treatment of the Holocaust will “resuscitate the past and make it present, invest it with a timeless immediacy.” That’s just what he does by using the present by way of his concept of “living words”—the recorded accounts from witnesses, bystanders, and perpetrators that use the rhetoric of inhuman death. Those who would argue that Lanzmann’s concentration on voices does not show the viewer the reality of the Holocaust must consider the nature of the words used in the testimonies given. We hear accounts that bodies piled atop one another resulted in a “flat slab” that the Nazis insisted on referring to as “figuren” and not “corpses.” Jews forced through narrow tunnels into the gas chambers experienced a rattling “death panic.” Suchomel, amid his many attempts to downplay his involvement, knowledge, and cooperation in the mass murder, also shares unforgettable and haunting details. At one point, he talks about how, before Treblinka started to use incinerators, the volume of corpses created a gas that lingered over the landscape like a mist. He describes Treblinka as “a primitive production line of death,” whereas the “murder machine” of Auschwitz was a factory. To be sure, the film achieves unforgettable imagery through the power of words.

The Holocaust becomes even more real as the viewer watches the pressure of memory and the past weighing on Shoah’s interviewees, the way witnesses do not look at Lanzman but search nowhere with their eyes to locate a memory. A major part of watching the film is seeing how human beings react and cope with their recollections. It is this quality that led Lanzmann to, in most cases, refuse his witnesses the time to prepare their remarks or stop their testimony. In a famous moment, Bomba, the barber, cannot go on. Lanzmann tells him “You have to” in a cruel but necessary directive. Lanzmann considers what it means to know the Holocaust—to have the horrors and lows of human atrocity locked inside one’s mind. When he interviews Michaël Podchlebnik, a survivor of Chełmno, the witness refuses to talk about his experiences at first. Observing Podchlebnik’s pleasant expression, Lanzmann asks, “Why does he smile all the time?” He smiles because he wants to focus on life, not the vast death he has witnessed. Another interviewee, survivor and camp resistance fighter Rudolf Vrba, smiles in another way. His grin represents discomfort—an incredulous sense of his horrific experience, as even though he’s survived it, he cannot believe it’s real, and he must share it to remember. Part of watching Shoah is discovering what we can observe about people, about humanity and its need to forget or, conversely, its need to remember.

It is almost strange that Shoah sears the viewer as it does, without the use of actual footage. And yet, there are dozens of stories in the film whose evocative use of verbal imagery have more veracity than the many volumes of Holocaust studies, textbooks, and dramatizations from Roman Polanski’s The Pianist (2002) to the Hungarian drama Son of Saul (2015). One cannot escape Shoah’s exploration of how the camps hid behind walls of trees in the countryside, away from metropolitan areas where rumor might spread, where they go unnoticed in Nature. How Jews arrived at Treblinka in cattle cars and, after two or three hours, they were dead. How the Nazis maintained an insane logic of cutting women’s hair prior to gassing them, as the beauty ritual calmed the victims before their death. How Jews who worked in trades (masons, electricians, tailors, etc.) were seemingly saved by the Nazis, who assured them by promising employment, and then convinced them to undress in the gas chamber for disinfection. How the path to the gas chambers was nicknamed “Ascension” or the “Road to Heaven.” How Jews who warned others of their impending death were thrown into the crematorium alive. How before the war, more than 80 percent of the population of Auschwitz was Jewish. The local synagogue was older than the local Catholic church. But now there’s no one to attend.

Why is it that, without seeing it, the account of Filip Müller, a Czech prisoner forced to work in the crematoriums, proves more devastating than any narrative dramatization? Müller says he gave up when a group of men and women from a Czech Family Camp began to sing their national anthem. It was the first time he had seen so many of his people since the start of the war, and he resolved to die with his countrymen. He entered the gas chamber to die. But a woman stopped him, arguing, “You must get out of here alive, you must bear witness to our suffering, and to the injustice done to us.” It is the power of real people and the viewer’s empathy working in tandem that makes such a story resonate beyond the dramatized accounts of the Holocaust provided by Hollywood filmmakers. And while such an account brings the desperation of the Holocaust into emotional reality, others depict how racism and indifference served genocide. Many claim “we didn’t know” the extent of the Holocaust. Some who use this line are former Nazis or, in one case, a Berlin woman who cannot be bothered to remember whether it was 40,000 or 400,000 Jews who died in Grabow. “I knew it had a 4 in it,” she says.

This moment reveals what political philosopher Hannah Arendt called “the banality of evil”—the notion of a fixed moral and ideological certainty that, through belief, law, and action, situates another group of human beings on a lower stratum, and in doing so, robs them of their humanity. Lanzmann briefly explores the history of such ideologies in Shoah during his interviews with Hilberg, the film’s sole Holocaust historian who argues that the Nazis did not originate the hatred of Jewish people, that the only thing original about their plan was the “Final Solution.” Hilberg observes that, given the historical hatred of Jews by the Egyptians and Babylonians, and given both Martin Luther’s book On the Jews and Their Lies and fourth century Christians who demanded exclusion and expulsion of the Jews, anti-Semitism was well established throughout history. Hilberg suggests the Nazis merely took those ingrained ideas and went a step further by carrying out an extermination plan. And whereas Martin Luther spelled out his solution for the so-called Jewish problem (“We are at fault for not slaying them,” he wrote), the Nazis hid their definition of the Final Solution within the bureaucratic language of their reports, documents, and paperwork. The extent of these moral foundations is evident throughout Shoah’s many interviews, and how they portraitize “the banality of evil” that allowed the industrialization of Jewish death to occur.

It is Lanzmann’s in their own words approach that reveals many of the most disturbing realities about the Polish witnesses whose animosity toward the Jews is never more apparent than in Chełmno, where the Poles now live in former Jewish houses and admit to having prospered in the wake of the Jewish absence. Lanzmann and Simon Srebnik make an appearance in the town, and the survivor is welcomed back at first. A crowd gathers around Srebnik, who remains silent as the Polish witnesses give their accounts of the gas vans that carted away Jews from the front steps of their local church—which is in the background of the shot, its doors open for a celebration of the birth of the Virgin Mary. The Jews’ luggage was filled with gold and riches, and left in piles nearby, the witnesses state. Lanzmann asks the locals how they knew gold was left in the luggage by the Jews. Although his question is never answered, the viewer suspects the worst: The Poles went through the luggage and kept the gold for themselves. When Lanzman asks why this happened to the Jews, the Poles answer: “Because they were the richest” says one person in the crowd. Then the local organ-player mentions that he witnessed a rabbi suggest the Jews were being punished for the death of Christ. At this, a woman from the crowd erupts, claiming it was “God’s will” that the Jew’s died. She quotes the Christian Bible to reinforce her statements, and many in the crowd nod in agreement. Lanzmann’s cameraman zooms in on Srebnik in this scene, which has gone from warm welcome to a repeat of the anti-Semitic rhetoric and anger that Srebnik once survived. Srebnik stands amid the crowd, quiet and smiling uncomfortably, smoking a cigarette. Suddenly the viewer sees how anti-Semitism remains within the population.

Lanzmann insists that he did not set out on a mission to expose Polish anti-Semitism, nor does the film hold judgments against the collective Polish identity; instead, he claims that no one had interviewed the Poles or talked to them about their experiences, and they were eager to tell their story. Lanzmann’s methods in these scenes have been challenged, as though he has gone to lengths to set up his Polish interviewees and catch them in a trap. But as Vice argues, “The Polish interviewees are the witnesses of the fate of others, and they are not asked about their own experiences, nor that of non-Jewish Poles who may have been killed or imprisoned in the camps. Shoah is not about the Poles or their behavior during the war, nor even their responses, but about the Holocaust and what they saw. For this reason alone they are not judged.” And though Lanzmann does not judge them outright, his interviews reveal behavior that has once again connected his film with a distant point in time. Specifically, Shoah links the footage assembled in the 1970s during the film’s long production to today, revealing strains of an attitude that threatens to descend into more than talk. It is the attitude that incited Polish lawmakers to enact a policy that would punish by force of law any association made between their country and the Nazi death camps, therein rendering discussion of the role of the Polish in the Holocaust forbidden.

If “never forget” seems to have been turned into a tagline at this point, Shoah asks that we think beyond a cold and distant historical summary or memorialization. It asks that we empathize with living witnesses and imagine their experiences. It asks that we think about the everyday lives maintained by the former Nazis, the engineers, bystanders, and brainchildren of mass death not as monsters but as possible neighbors. Lanzmann finds one of them, Joseph Oberhauser, a Bełżec extermination camp functionary, working in a Munich pub, his fellow employees seemingly unaware that he served four-and-a-half years of prison time for his hundreds of thousands of counts of accessory to murder. “Never forget” places the Holocaust in one’s memory rather than confronting the conscious mind with the traumatic reality of its existence. If left to our memories, historical accounts, dramatizations, or textbook facts to tell the story, it can be questioned and denied, its potency subdued, as it has been in the decades since the 1940s. Distanced objectivity, even dramatic consumption of the Holocaust through based-on-a-true-story fiction makes way for a numbing effect; it becomes a period in history to be treated with respect and mournfulness, as opposed to a reality that was made possible not only by Nazis but by silent and even complicit witnesses stretching from Poland to the United States. As Lanzmann wrote in the late seventies, treating the Holocaust as mere history gives the anti-Semite an opportunity “to regain the unhindered right to kill again.”

Lanzmann chose his title well. “Holocaust” is a word that had been used throughout history to describe mass killings, but its origins from the Greek holos (meaning complete or whole) and kaustós (meaning burnt) suggest a burning at the altar, a sacrifice in the appeasement of a pagan god. In Hebrew, the word shoah makes no such association, although some have questioned its use in this context, given its original meaning. It is a word for annihilation, darkness, and destruction, but without a sacrificial association. Its use implies a natural disaster of sorts, a whirlwind. According to the Israel-based newspaper Haaretz, the word was first used to describe the extermination of the Jews in 1938, by writer Yehuda Erez in an article entitled “With the Shoah in Europe.” Orthodox Jews have been referring to those events as shoah ever since the late 1930s. The distinction between a sacrificial burning and destruction without an implied motive is an important one, as it underscores the senselessness of what occurred—and a world seemingly determined to ignore the wiping out of a culture. Lanzmann’s film contains many episodes and aspects of the Holocaust, but above all, he presents a portrait of an almost businesslike everyday world in which it happened and could happen again.

Throughout Shoah, Lanzmann locates poignant images of pedestrians passing through the contemporary remains of several concentration camps. A brief shot inside of the now-crumbling Auschwitz finds a boy walking his bike through the grounds. Is this part of his routine? Is there no other road for him to take? Images such as this suggest that acceptance has occurred. People have healed, moved on, or were never made aware, which represents the acceptance of their elders and teachers. But Shoah wants and needs its audience not only to remember but experience the full trauma of the past. It is a refiguring of the popular notion that a few Nazi madmen conceived the “Final Solution” at the Wannsee Conference in January 1942, following directives from Adolf Hitler, and proceeded to carry out the mass “evacuation” of the Jewish people. Vice notes that Lanzmann sought to uncover not a return to the past but a return of the past to the present, exposing how traces of the Holocaust flourish even today in the bureaucratic allowances that enable anti-Semitism. Indeed, the rhetoric continues as neo-Nazi parties gain momentum around the globe and have been permitted to make public demonstrations. Poland’s recent law also attempts to rewrite history, removing responsibility and inciting people to forget, deny, and move on. Inch by inch, those who would do harm to Jews once more gain the ground to do so. In this climate, Shoah feels more essential than ever, demanding that its audience not just mourn and monumentalize the past, but experience it. And through this experience, we are better equipped to identify and oppose signs of the past repeating itself in our contemporary world.

Bibliography:

Arendt, Hannah. Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. Penguin, 1963.

Hirsch, Joshua. Afterimage: Film, Trauma And The Holocaust. Temple University Press, 2004.

Lanzmann, Claude. Shoah: An Oral History of the Holocaust. Pantheon Books, 1985.

—. The Patagonian Hare: A Memoir. Atlantic Books, 2012.

—. “Seminar with Claude Lanzmann.” Yale French Studies 79. November 1990, pp. 82-89.

Liebman, Stuart, editor. Claude Lanzmann’s ‘Shoah’: Key Essays. Oxford University Press, 2007.

Lipstadt, Deborah E. Denying the Holocaust: The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory.The Free Press, 1993.

“New Survey by Claims Conference Finds Significant Lack of Holocaust Knowledge in the United States.” ClaimsConference.com. 12 April 2018. http://www.claimscon.org/study/. Accessed 1 March 2019.

Vice, Sue. Shoah. BFI Film Classics. Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review