The Definitives

Seven Samurai (1954)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai marks a convergence of art and entertainment that has never been surpassed in the history of filmmaking. At once an exciting action picture and an incisive look at the dimensions of humanity, Kurosawa’s universal story appeals to all audiences, regardless of age or culture, because the Japanese master uses an array of cinematic and narrative methods that transcend demographics or nationality. Blending Western formal techniques with themes rooted in Eastern history, he generates near tangible energy onscreen with expert editing and innovative camerawork. When viewing this 207-minute epic, the film plays like a tight, efficient story trimmed of any unnecessary scenes; it absorbs the audience in a visceral, funny, compelling, heartening, and kinetic experience—perhaps the most enjoyable yet intellectually rewarding undertaking ever put to film. Kurosawa reaches beyond simple escapism, developing natural relationships between the characters, so we get to know them, their personas, and their individual philosophies. His film grapples with history, culture, and the human experience with the same intensity and grandeur as his battle sequences. Seven Samurai is a spectacle of the human spirit, an interplay of hope and questions about the way of the world, and finally, an epic in which ideas and action converge with a remarkable scope and depth.

Known as “The Emperor” in Japan for his status as the country’s preeminent filmmaker and his authoritative approach, Kurosawa worked primarily as an arthouse filmmaker until 1953, the year he began production on this masterpiece among several masterpieces in his career. Kurosawa had already achieved worldwide acclaim for Rashomon, his brilliant multi-perspective platform from 1950, which, for the first time, single-handedly attracted interest from the global film community to Japan. For his next picture, Kurosawa set out to make an allegorical samurai film to reignite an otherwise dead genre in postwar Japan, the jidaigeki, or period film. Although Japanese productions had produced countless samurai films with chambara, period films rooted in sword fighting, they weren’t strictly a classical or historical jidaigeki, in that chambara often ignored the meaning of the past as it applies to contemporary Japanese culture. Kurosawa sought to embrace the realism of history so frequently denied by chambara films, but also activate realism into something “entertaining enough to eat” as he would say—something both the erudite and the common could devour, a film loaded with thematic and energetic richness. To this end, Kurosawa paints with epic, historically precise, and philosophic brushstrokes, allowing Seven Samurai to transcend genre and cultural limitations to become a universally consumable motion picture.

The story of Seven Samurai is deceptively simple: a poor farming village in sixteenth-century feudal Japan is threatened by bandits. In desperation, community members vote to fight rather than allow the bandits to raid another year’s essential rice crop. However, realizing that they know nothing about battle, a wise elder orders them to hire samurai to protect their home. Village representatives discover that recruiting samurai willing to fight without the promise of glory or payment is nearly impossible. Fortunately, they encounter Kambei (Takashi Shimura), an honorable do-gooder who assists them in finding and auditioning potential candidates, offering only food and shelter, and, of course, the thrill of battle. When the peasants and Kambei eventually find six other willing samurai, they are men who relish combat, need little, and feel compelled to do what’s right. Infusing the farming community with a sense of unity, the samurai train the peasants to fight and defend themselves, constructing walls and digging moats, while also teaching offensive tactics. When the bandits eventually arrive to plunder the village, a battle ensues, resulting in the deaths of several samurai and farmers but ultimately leading to victory. The spring rice-planting season comes quickly, and with no bandits left to confront, the three remaining samurai are no longer needed. The samurai and farmers part ways.

To understand how such a simple, familiar tale could become one of cinema’s greatest treasures, one must understand the setting. Early 1950s Japanese cinema relied on a very specific sense of nationalism, from a storytelling point of view. Japanese filmmakers worked in two major categories: gendaigeki and jidaigeki, both in which any number of genres could function. The former category, gendaigeki, takes place exclusively in contemporary settings and focuses on the modern day world. Jidaigeki unfold in historically set films, employing settings that range from Japan’s Heian period (794-1185 A.D.) to the Meiji period (as late as 1912 A.D., when Emperor Meiji died). They use a selection of craftsmen, farmers, merchants, noblemen, sex workers, and, most commonly, samurai as their choice characters. Frequently, swordplay films known as chambara (an onomatopoeia word for swords clanging), a subgenre within jidaigeki reliant solely on action (an equivalent to Western gunslinger movies), dominated the category. Samurai dramas and epics outside of chambara were a longstanding tradition in Japanese film, drawing from a rich literary and storytelling tradition. Established tales like those of The Loyal 47 Ronin and Miyamoto Musashi were repeatedly produced in Japan, as much as once every few years, until after the Second World War, when samurai ideals no longer aligned with the United States Occupation’s postwar statutes over the Japanese filmmaking industry.

Real samurai existed in Japan from the late twelfth century until an industrial, militarized society overtook the country with the Meiji Restoration in 1868. In some cases, samurai held the status of nobility; elsewhere, they functioned as bureaucrats. Their most common designation was that of a warrior. In Japan’s sixteenth-century feudal period, the country was ruled by a shogun of the Imperial Army: the power behind the representational figurehead of the Emperor. Across warring states, warlords known as daimyo controlled individual clans, fighting great battles while vying for power. Devoted to their daimyo, samurai were committed to death, even suicide (called seppuku or harakiri) on their lord’s command. And should their lord die, samurai would become masterless wanderers known as ronin. Samurai followed bushido, a code meaning “Way of the Warrior,” containing edicts on how samurai live their lives, remain loyal, stay self-disciplined, and build their ongoing existential and physical growth. Bushido requires that samurai become authorities in martial arts, poetry, calligraphy, and philosophy, surpassing individualism and selfishness. Experts in Zen-Buddhism and swordsmanship, samurai devoted themselves to honor. But if samurai became masterless ronin, they were prevented from undertaking peasant manual labor for pay, and so they would become nomadic. Many would travel about between dojos (martial arts schools), honing their skills, accepting a night’s sleep and a meal in exchange for a lesson, or winning their room and board by defeating the dojo’s instructor. Other ronin would take odd jobs that utilized their skills, while others still resorted to criminality.

In the years preceding World War II, Japanese culture embraced a simplified version of samurai honor in military applications, linking kamikaze warriors willing to die for their imperial army to the blind loyalty of samurai to their daimyo. Death was met openly and without hesitation in both cases. When Japan surrendered, ending the war, the Japanese people were struck with a vast ambiguity and uncertainty that penetrated their selfhood. With Japan’s war lost, the U.S. occupational forces that implemented an enforced democracy oversaw the Japanese film industry and required pre-approval of all film scripts prior to their production. For the Occupation’s authorities, the samurai film represented a sense of Imperialist Japan’s nationalism, therefore incongruous for the new, reformed, democratic Japan. Samurai films during the Occupation would have implied an unquestioning, death-driven loyalty to a lord—an anti-democratic notion. With a lacking samurai presence in Japanese culture, the samurai’s sense of honor and loyalty also disappeared. Japan’s culture took an Americanized dive, resulting in rampant crime and disillusion, as well as the emergence of highly organized yakuza gangs (something Kurosawa recognized and addressed in his postwar pictures, 1948’s Drunken Angel and 1949’s Stray Dog). Only after the Occupation ended, effective April of 1952, did jidaigeki samurai films reemerge.

With Seven Samurai, Kurosawa hopes for understanding between the polarized peoples in his newly reformed culture—those willing to embrace past ideals, and those lost contemporaries looking to redefine themselves. He does this through a historical and narrative allegory, linking his contemporary opposition between the past and present cultures to his film’s distinct parties: farmer and samurai. Instead of burying the past under a veil of his present-day postwar despair, known as the “kyodatsu condition,” Kurosawa sought to reincorporate a relevant past to revive the Japanese Self, which could draw on and benefit from the venerable code of the samurai. And yet, in the strictest definition, the samurai hired by the farmers are ronin and are not technically samurai; they are beholden to no master beyond their own personal discipline to “The Way of the Warrior.” In Roger Ebert’s appreciation, he suggests these samurai simply follow “the roles imposed on them by society,” as if they merely fulfilled some preordained behavioral directive by helping the farmers. But pride can obstruct such directives, as we see early on when the farmers approach a husky samurai who shouts in refusal, insulted that they would offer such absurd terms for his services. For the seven samurai hired by the farmers, taking on such unrewarding, surely bleak circumstances attests to their individual ethos. While the peasants remain unable to offer more than rice and a warm bed, each ronin chooses a humanist’s devotion to samurai honor by accepting their terms. The title does not refer to them as ronin, but samurai, because based on their selflessness on behalf of the farming village, each remains true to the mores established in bushido code.

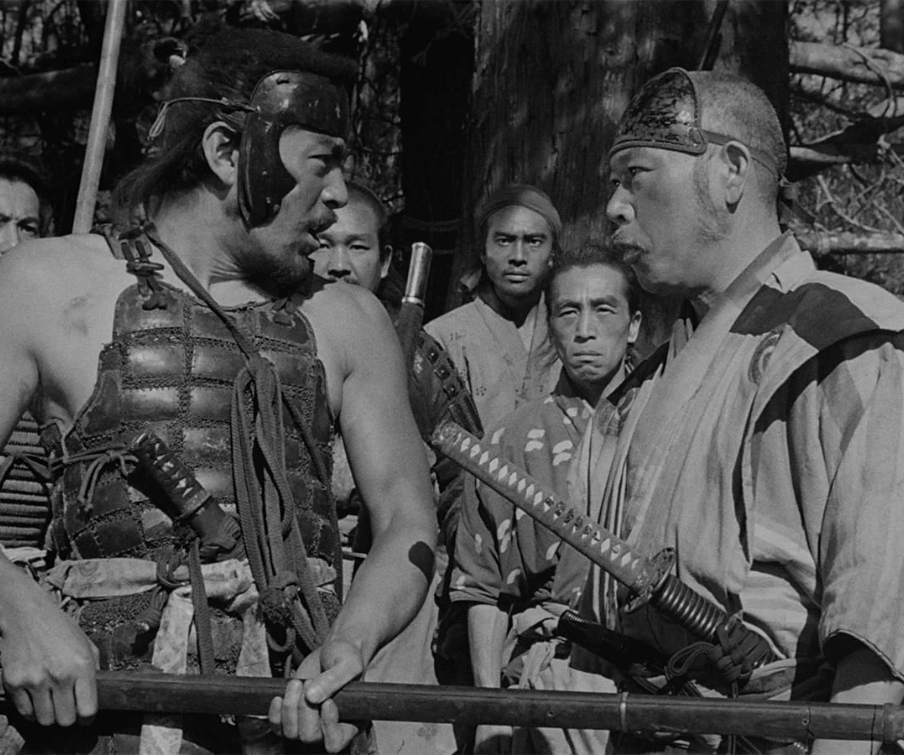

Kurosawa’s humanism rests in his seven heroes, each with a specific, cohesive personality introduced in the film’s first hour. Kurosawa portrays them as a congenial and honorable bunch, making their ensuing deaths more profound for the viewer. Developing the samurai characters involved establishing seven distinct personalities, one of many aspects of the film’s production labored over by Kurosawa. When the farmers first meet their samurai leader, Kambei, he displays profound humility and bravery, defying the farmers’ prejudices against the masterless warriors. A crowd gathers around Kambei, an elder who kneels by a stream and proceeds to shave off his topknot. A samurai losing his topknot infers punishment or his induction into the priesthood—either way, with no topknot, he no longer remains a samurai. (Indeed, several filmic samurai have been shamed after losing their topknot; in Masaki Kobayashi’s masterful 1962 film Harakiri, actor Tatsuya Nakadai’s character simply cuts off the topknots of his enemies, knowing shame will drive them to commit seppuku.) But Kambei’s sense of honor is more significant than such superficial illustrations of the samurai code. Once Kambei’s head is smooth, he dresses in priest’s clothing, and then he uses the disguise to cut down a kidnapper holding a child hostage. By doing this without accepting a reward for his actions, Kambei is plainly the ideal candidate for the farmers to lead their bandit resistance. When they ask him to join, he accepts their proposal, continuing with the recruitment process himself.

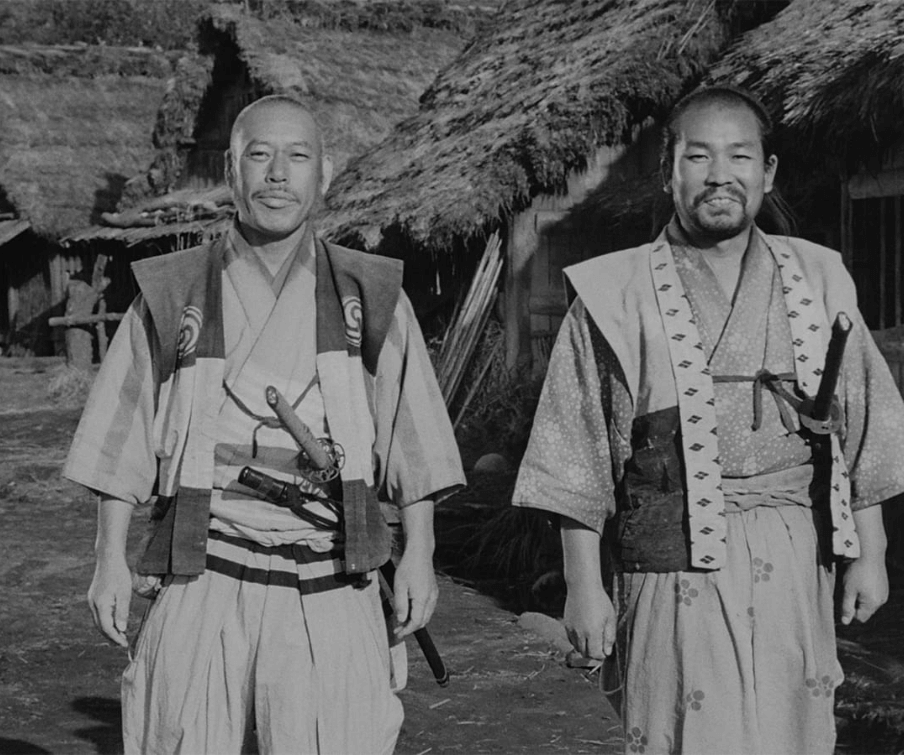

Kambei’s sense of honor becomes the selling point to other samurai teeter-tottering on whether or not to join the farmers’ David and Goliath fight. The other samurai join because Shimura’s character is so “interesting” or noble, a rare trait among ronin. Kambei believes in facing reality. Nothing surprises him. All one can do is his best, mainly for others—even if, as in the farmers’ case, it means facing the impossible. Kambei embodies model heroism and selflessness. Shimura plays him worn and dignified, not dissimilar from his character Watanabe in Kurosawa’s delicate drama Ikiru (1952), arguably Shimura’s best performance, given two years prior to his role in Seven Samurai. Notice also Kurosawa’s dedication to continuity on Kambei’s shaved head; after shaving off his topknot, his hair slowly returns as the film progresses. Kambei takes long, ponderous moments, rubbing his fuzzy top, a stark symbol of his human spirit and a reminder of his sacrifice, as he works through a given problem. Shimura and Kurosawa’s partnership would last longer than even the Kurosawa-Toshiro Mifune affiliation, but Mifune would prove to be the more admired actor, on the whole, due to this film and many others. And yet, while Seven Samurai’s extensive success made Mifune Japan’s most popular star, Shimura’s performance is the film’s center. Moreover, up to this point in Japanese film, filmmakers often portrayed samurai as supermen or larger-than-life heroic figures. But Kambei’s humanist traits glow around him like an aura, at once grounding him and rendering him dignified and chivalrous.

Each of the seven samurai is equally distinct and played by members of Kurosawa’s stock company. Gorobei (Yoshio Inaba), the second to join, signs up because of the principled quality he sees in Kambei; though he understands the farmers’ plight, he tells Kambei, “It’s your character that I find most compelling.” Good-humored and particularly smiley, Gorobei becomes Kambei’s second in command, handled with gracious warmth by Inaba. Daisuke Kato plays Kambei’s former soldier Shichiroji. Pudgy, yet a fruitful warrior, he joins without an instant of hesitation. He fights for his love of battle, not for money or rank. “This may be the one that kills us,” Kambei warns. Shichiroji’s face slowly raises a smile. Perhaps Shichiroji seeks to finally achieve The End through an honorable death, but alas, he is one of only three living samurai at the end. When asked if he has killed many, the fourth samurai, Heihachi Hayashida (Minoru Chiaki), replies, “There’s no cutting me off when I start cutting. So I make it a point to run away first.” Gorobei recruits Hayashida, finding him chopping wood for a meal. Far from a prime martial artist, the character is hired to lift morale, allowing both the villagers and fellow samurai a hearty laugh amid distress. Based on legendary Japanese warrior-poet Miyamoto Musashi, master swordsman Kyuzo (Seiji Miyaguchi) initially turns down Kambei’s offer to protect the farmers. But then he appears before the group one night, joining without explanation. And surely, no explanation is needed. Kambei witnesses Kyuzo’s talent during a Western-like duel, where his sword strikes with an elegance, speed, and class few other samurai could achieve. During the farmers’ battle, Kyuzo, like each of the other three samurai who fall, dies by bandit gunfire; no sword or spear could ever take down this paladin—only the blunt, unskilled attack of a gunshot.

Amid the trained and noble warriors, there are two exceptions. The adolescent Katsushiro (Isao Kimura), though from a noble family and not trained extensively in bushido convention, recognizes Kamei’s greatness when he sees it and follows him like a puppy. Katsushiro is introduced after Kambei cuts down the kidnapper, before he ever agrees to fight for the farmers. Kambei moves along without the need for due praise; the farmers trail behind in a nervous pack, egging each other on to approach him. All at once, the would-be disciple Katsushiro advances, begging for Kambei to teach him. Despite making an eager assistant, Kambei later rejects the idea of including Katsushiro in the seven. “Kids work harder than adults,” Hayashida defends, “But only if you treat them like adults.” Kambei concedes. Later, in the village, the pubescent Katsushiro frolics in a flower field and finds a sweetheart in village farmgirl, Shino (Keiko Tsushima)—with whom he exchanges a number of wide-eyed glances and even a brief roll in the grass. His ongoing courtship with Shino adds romance to the list of genres found in Seven Samurai, a seemingly endless source of varied tones and passages. And along with Kambei and Shichiroji, Katsushiro remains one of the three surviving samurai.

The other exception to the warrior rule is Kikuchiyo, in the role that solidified Toshiro Mifune as an international star. Kikuchiyo is, in fact, not a samurai or ronin at all. A stray vagrant putting on airs to attain the glory of battle, Kikuchiyo begins as the film’s comic relief, boasting about his prowess in a drunken stupor, carrying a sword much longer than any of the other samurai—an ironic phallic symbol if there ever was one. But Kikuchiyo overplays his masculinity, coming off as buffoonish to the other six he strives to emulate. Even after the others drive him away, Kikuchiyo trails along with their group, several paces behind. He invites himself back to the farmers’ village, determined to assert his battle-readiness with harsh fighting words, mocking insults, and slapstick displays of horsemanship. Mifune’s reputation as an unhinged Japanese actor began much earlier than this Seven Samurai with pictures like Drunken Angel and Rashomon; however, his status skyrocketed with this role—an irrespressible performance. He bursts into performative laughter, tongue out, making crossed-eyes, desperate to prove both his manhood and honor, which are sometimes at odds with the bushido code. Still, Kurosawa conceived Kikuchiyo’s tragic figure as a living bridge between peasant and samurai. He embodies the film’s theme of modernity and history fusing into a postmodern philosophy—the very meaning of Seven Samurai is contained in this one character.

Kikuchiyo aspires to become a warrior, but he later admits that he was born a farmer’s son, and so his presence amid the seven samurai connects the two groups, farmer and samurai. He also demystifies both stations in the film’s most powerful speech. After discovering the farmers’ cache of stolen samurai weaponry, which they have taken from injured or vulnerable samurai whom they killed after wandering into their village, he scorns his comrade warriors for being surprised at the farmers’ predatory instinct:

“What did ya think these farmers were anyway? Buddhas or something? Don’t make me laugh. There’s no creature on earth as wily as a farmer! Ask ‘em for rice, barley, anything, and all they ever say is, ‘We’re all out.’ But they’ve got it. They’ve got everything. Dig under the floorboards. If it’s not there, try the barn. You’ll find plenty. Jars of rice, salt, beans, sake! Go up in the mountains. They have hidden fields. They kowtow and lie, playing innocent the whole time. You name it, they’ll cheat you on it! After a battle, they hunt down the loser with their spears. Listen to me! Farmers are misers, weasels, and crybabies! They’re mean, stupid, murderers! Damn! I could laugh till I cry! But tell me this: Who turned them into such monsters? You did! You samurai did! Damn you to hell! In war, you burn their villages, trample their fields, steal their food, work them like slaves, rape their women, and kill ‘em if they resist. What do you expect ‘em to do? What the hell are farmers supposed to do?”

Kikuchiyo exposes that the farmers have murdered vulnerable samurai in the past, while samurai have a reputation for exploiting farmers. His words shame both parties, leaving them humbled and willing to forgive their respective misdeeds for a grander sense of solidarity. Kikuchiyo represents Kurosawa’s most inspired turn of character, since he begins as a clown but later supplies the defining moment that joins the villagers and samurai in a marriage of democratic ideals. Consequently, Kikuchiyo proves himself a warrior, advancing from farmer to samurai; he rises to accomplish the most significant single act performed by one of the seven when, in the final battle, he dies honorably just after killing the bandit leader, living up to that longsword.

Kikuchiyo’s evolution into a samurai also underscores Kurosawa’s harsh representation of violence in the picture—harsh in that he avoids romanticizing violence. Part of Kikuchiyo idealizes battle, like a child who glorifies the violence of a comic book or movie without realizing the reality of death. Washed over with dreams of samurai honor, he ignores the bloody potential of the farmers’ conflict. But Kurosawa’s violence is unflinching and real; every death hurts, with victims falling into the sloppy mud below. How easy it would be if the bandits’ deaths were somehow cathartic and vindicating, but Kurosawa gives us a scene that acknowledges the reality of the situation: A bandit scout finds himself caught, and, despite protests from the samurai, is executed by a savage mob of angry farmers. Inelegant, and certainly dishonorable, such ignoble violence outside of The Battle is frowned upon by Kambei, and by extension, Kurosawa. By blurring the dynamic between samurai honor and the farmers’ innocence, Kurosawa asserts that there is no victory by means of bloodshed alone.

Instead, victory presents itself in, what Kambei hopes will be, an ideal trust between two communities, reaching back to Kurosawa’s intended metaphor, where pre-industrial and postwar Japan find common ground. In Kikuchiyo’s search for equilibrium between farmer and samurai, he realizes noble perseverance remains a samurai’s true mode. This philosophy sustains each of the seven samurai, but it is through Kikuchiyo that the audience understands why, in the beginning, such talented warriors would take on this daunting task for so little in return. His advancement signifies the possibility of creating a bridge between historical and modern truth. Thematically, the character’s growth reconciles Japan’s past with its confused present. Perhaps this is why Kikuchiyo’s death is so devastating: he connects the samurai, who are tempted to sack the village, with the farmers, who are so afraid of the samurai that they hide their women. When Kikuchiyo, the last bastion of hope, dies, we realize any chance for common ground is impossible.

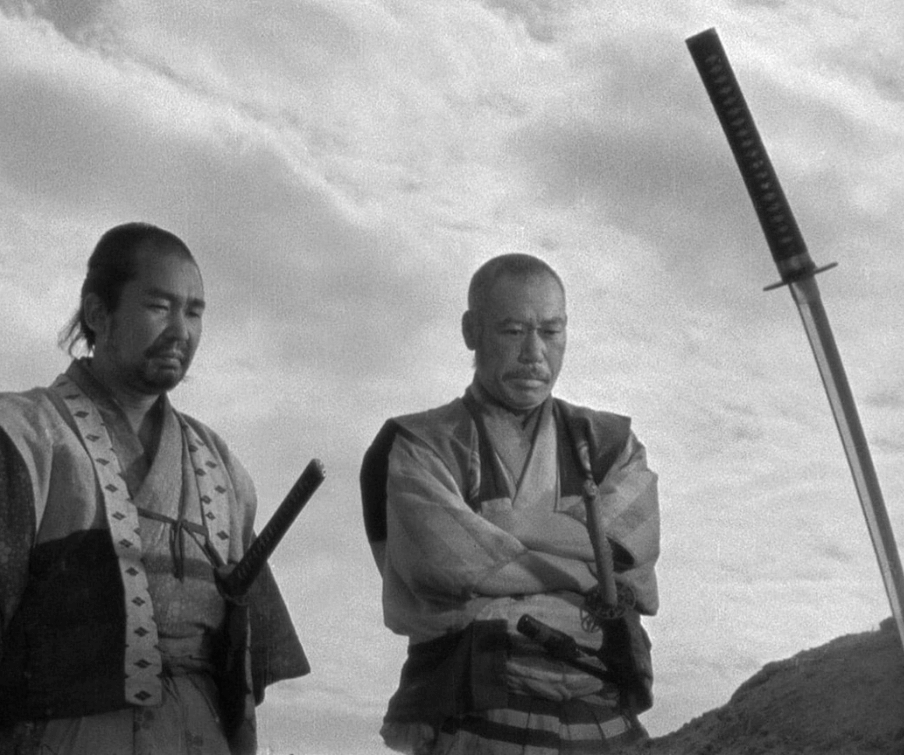

The victory over the bandits notwithstanding, Kambei laments with the closing line of dialogue: “In the end, we lost this battle too.” All around the three surviving samurai, the newly safe farming village sparkles with life: a planting festival, with beautiful music and dancing, shines in the distance. And now that the deed is done, the peasants’ eyes once again become suspicious and guarded, just as Kikuchiyo described; with their routine back to normal, it’s clear the farmers wish the samurai to leave. For the survivors—Kambei, Shichiroji, and Katsushiro—the battle was meaningless, simply the thing to do, without reward, perhaps insane, certainly quixotic. What Kambei’s grief suggests is that, still, the farmers do not trust the samurai; he hoped the farmers would become closer to the samurai after their shared battle. The reality: farmers are farmers, samurai are samurai, bandits are bandits. The three cannot intermingle. Though it may seem that Kurosawa ultimately posits false hope for democratic idealism with Kikuchiyo’s death and the farmers’ rejection of the samurai, the act itself has meaning and yearns for a better future.

The earliest ideas for Seven Samurai began with Kurosawa’s desire to reclaim the jidaigeki samurai genre by way of palpable entertainment—and certainly, much of his rhetoric on the film’s concept occupies the aforementioned consumption metaphor. As Kurosawa explains, “I think we ought to have richer foods, richer films.” When he first began exploring the premise of a samurai film that would fold the past into the present, Kurosawa spent weeks researching details that would enrich his project’s historical realism. That’s when he discovered an article about a group of villagers who hired a samurai to protect their village from bandits. Writers Shinobu Hashimoto, Hideo Oguni, and Kurosawa used this account as a launchpad and elaborated from there, filling the story with more bandits and more samurai for an agreeably epic scale. Oguni did none of the actual writing, even though he received credit; however, he steered the story by overseeing Kurosawa and Hashimoto’s writing process—wherein, famously, the three credited writers holed-up in a hotel room for roughly six weeks, not allowing themselves to leave until their script was perfect. This was time well spent. Seven Samurai feels economical and pointed yet thrust forward through narrative efficiency. Each scene is purposeful and adds to the story, building a character, deepening the story, or reinforcing a theme.

Filming began in May of 1953, under Toho Company Ltd., for a planned three-month shoot. By August, only one-third of the script was in the can and most of Kurosawa’s budget was spent—$200,000, far exceeding standard budgetary caps in Japan’s film industry at the time. Kurosawa’s obsession for detail wore on both him and the production. The film’s price tag drove upward, and he was hospitalized with exhaustion a number of times, so delays persisted. Kurosawa’s ancestors from the previous century were samurai, conceivably motivating his personal dedication to the project’s authenticity; then again, throughout the middle renaissance of his career, the director was known for similarly arduous productions, often tiring himself to the point of exhaustion. On hiatus, Kurosawa spent all of September 1953 defending his directorship to Toho executives, who contemplated replacing him. Long before this production lull, however, Kurosawa foresaw potential power struggles and was clever enough to forgo filming the film’s climactic ending battle sequence until the last, keeping Toho on the hook. Shooting resumed October 3rd and continued until the following spring.

Kurosawa’s massive, expensive film drew attention to his directing style, notably his penchant for dictating commands like a military commander—leaving the occasional actor in tears or humiliating someone who had forgotten their lines. All of this was covered thoroughly by the Japanese media. Kurosawa was believed to be tyrannical by many, and his alleged autocratic control over every detail might not have appealed to his lesser actors, but the onscreen result of his supposed harshness remains undeniably sound. On the other hand, members of Kurosawa’s regular acting troupe—such as Toshiro Mifune, Takashi Shimura, Tatsuya Nakadai, Minoru Chiaki, and Kamatari Fujiwara—have attested to the director’s affable nature, despite a cross-section of his more sporadic castmembers thinking him intolerable. His publicized title “The Emperor” remains an overly simplified label, equated with Alfred Hitchcock’s “Master of Suspense” brand name or Ernst Lubitsch’s “Lubitsch Touch”—all tags summing up only the most popularized interpretation of the director’s work, or, in this case, Kurosawa’s approach to directing.

Stories from Seven Samurai’s set emerged in interviews with the cast and crew, describing Kurosawa in the prime of his publicized, detail-obsessed persona. For the farmers’ village and overall shooting locale, he scouted for months to find the perfect setting, which he sketched out in his head long before principal photography. Throughout five locations, Kurosawa erected assorted sections of the farming village to match where, visually, their location made the most sense. He also devised a registry of the village’s 101 members (just as Kambei keeps a list of remaining bandits)—including names, occupations, and other minor details—and required that all on-set actors, speaking lines or not, refer to each other in their characters’ names. With such order, Kurosawa could track continuity throughout his production, allowing even anonymous or background villagers a pulse.

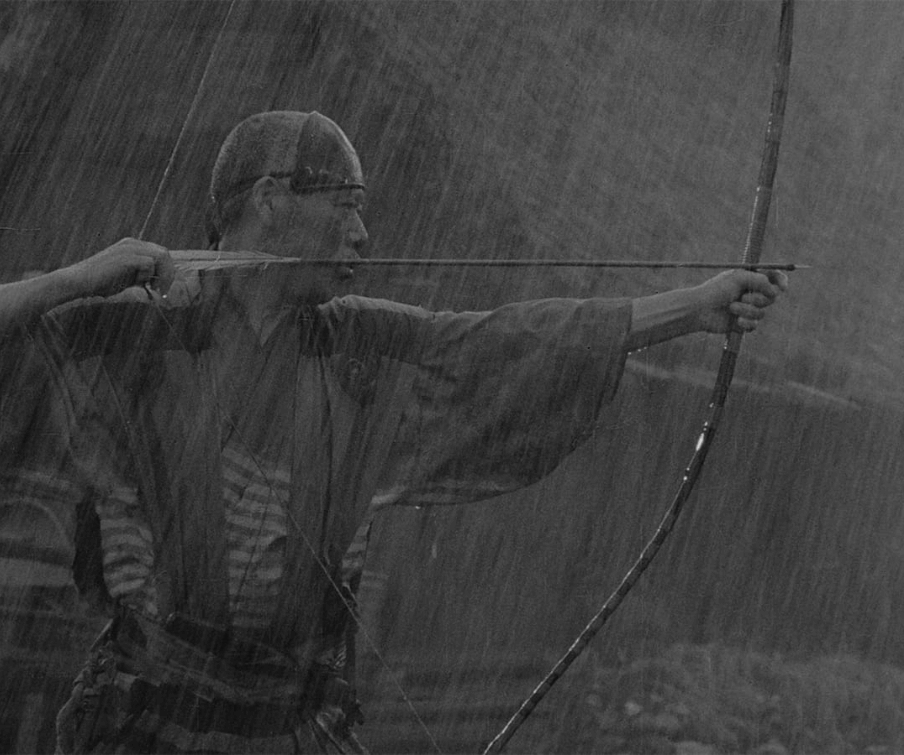

Kurosawa shoots his action with frequent use of deep focus, capturing the fore, middle, and background with multiple cameras and longer lenses. More cameras working at once meant better views of the action, and efficient creation of space through editing. Capturing the battle from numerous angles did not aestheticize his violence into graceful interplays of warrior and bandit, however—the viewer feels each death. Kurosawa remains dedicated to realism on all fronts. In each case, death is clumsy, unforgiving, and unsophisticated. Several significant deaths are represented with slow motion, so that we might ruminate over their meaning, while others, like Kikuchiyo’s, play out at regular speeds, their importance eclipsed by the chaos of battle. And just as he labored over the grand schemes of action and setting, Kurosawa did not fail to overlook the minor details or beauty. Shino’s eyes, for example, always seem to capture light. This is because Kurosawa ordered that reflective mirrors, held at just the right angle, be used to create a sophomoric innocence in the character’s massive round eyes. Kurosawa and cinematographer Asakazu Nakai create no end of stunning images and compositions, from clarity and intensity of the action to the poignant final shot of the swords in the fallen samurai’s graves.

Filming the final battle under grim conditions proved almost as punishing as the events depicted in the film. Shot during the winter, artificial rain machines created the film’s downpour for the final battle, all but giving the crew frostbite but creating a wonderfully dramatic effect in the process. Actors sloshed through inches of near-frozen mud, their strained efforts unmistakable onscreen. Most wore period-accurate moccasins and thin clothing, as the film takes place just before planting season, leaving their bodies exposed to the elements. In spite of the trials his cast and crew endured due to his obstinate attention to detail, Kurosawa’s film wrapped up in March of 1954. Fumio Hayasaka added the film’s iconic, stirring, delightful music—he had already composed for Kurosawa on Rashomon and Ikiru, among others—becoming the first Japanese composer to receive sole screen credit for his work. After editing, Seven Samurai would become the longest and most expensive Japanese film then produced, costing around $560,000, more than twice the original budget.

And yet, the film was one of Toho’s biggest money-makers of that year, despite its more than three-hour running time and price tag five-times the size of a normal Japanese film. Film critics the world over adorned the film with plentiful accolades, hailing it as a watershed not only for the Japanese film industry but for cinema as a whole. But because early reviewers mildly complained about the film’s length, Toho cut the picture in 1956 to 155 minutes, selling the gutted product to Columbia Pictures for U.S. distribution. The abbreviation removed several crucial subplots, and in tow, much of Kurosawa’s social commentary. Toho reissued the longer version into Japanese theaters in 1975 and 1991, and though these screenings proved successful, the full film eluded international audiences. Americans extolled high praises for the abridged cut, regardless. In 2003, a 203-minute cut earned a theatrical reissue on American soil, reinvigorating love for and attention to Kurosawa’s greatest accomplishment. Not until 2006, when The Criterion Collection released the entire 207-minute film on home video, complete with an improved subtitle translation and crisp digital cleaning, was Seven Samurai finally restored to its whole, stunning visual and narrative clarity.

Over the years, remakes, inspirations, and down-right thieveries would draw from Seven Samurai’s commercial and artistic victory. The most popular of these derivations is, of course, American director-producer John Sturges’ The Magnificent Seven (1960), which spawned a number of sequels and a television series. Sturges adapted Kurosawa’s masterpiece into an American Western, giving the film, but not Kurosawa or his other two writers, screen credit. Notable score by Elmer Bernstein aside, Sturges’ film lacks the majesty and philosophy behind its heroes and conflict. As Kurosawa would say, appropriately and succinctly, “Gunslingers are not samurai.” Indeed, the cowboys remain a vagrant bunch with no written maxim to follow, and their employment by Mexican farmers bears no significant social, political, or philosophical implications. The resultant movie offers expert Western amusement thanks to Sturges’ direction, and fine performances by stars Yul Brynner, Steve McQueen, and Charles Bronson, but leaves viewers with an empty stomach in comparison. Other minor inspirations include India’s most successful film of all time, Sholay, released in 1975, which took the skeletal outline of Seven Samurai for a Bollywood version that ran for more than five years in India, advertised as “The Greatest Story Ever Told!” Fans of Pixar Animation Studios will also recognize Seven Samurai’s framework in A Bug’s Life (1998), which replaces samurai with assorted insect circus performers enlisted to rescue a farming colony of ants from grasshopper-bandits. In 2004, a Japanese anime series entitled Samurai 7 even attempted to retell the story in a postmodern futuristic world; over 26 episodes, the program touches on several themes from its source but fails to address Kurosawa’s widespread historical themes.

What remains miraculous about Seven Samurai is how seamlessly it balances sheer entertainment with profound, enduring themes, meticulously detailed period mise-en-scène, and an unmatched cinematic ambition. Kurosawa’s film still feels potent, exhilarating, thoughtful, and deeply moving—hallmarks of his desired esculent quality—while none of its many remakes or offshoots come close to matching its dramatic power. His profound synthesis of action and purpose offers complexity for art film enthusiasts while delivering an enthralling spectacle for general audiences. Cinema so rarely achieves such a balance, and never so astonishingly well as Kurosawa’s masterpiece in a career of masterpieces. This alone affirms its place among the greatest films ever made. Seven Samurai demands multiple viewings; each reveals new subtexts and visual intricacies that deepen its impact. With every screening, the film grows richer, solidifying its status as an inexhaustible cinematic achievement—an enduring text with limitless discoveries waiting to be found.

Bibliography:

Galbraith IV, Stuart. The Emperor and the Wolf: The Lives and Films of Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune. Faber and Faber, 2002.

Goodwin, James. Akira Kurosawa and Intertextual Cinema. Johns Hopkins University Press, c1994.

Kurosawa, Akira. Something Like An Autobiography. Knopf: distributed by Random House, 1982.

Richie, Donald. The Films of Akira Kurosawa, Third Edition, Expanded and Updated. With additional material by Joan Mellen. University of California Press, 1996.

Richie, Donald; Schrader, Paul. A Hundred Years of Japanese Film: A Concise History, with a Selective Guide to DVDs and Videos. Kodansha International: Distributed in the U.S. by Kodansha America, 2005.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review