The Definitives

Scream (1996)

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Wes Craven’s Scream opens with a scene greater than the remainder of the film, even the remainder of the franchise. A phone rings. Drew Barrymore, playing the teen Casey, answers. Sorry, wrong number. A shot outside establishes an isolated house, with no help for miles. Home alone and roasting popcorn for movie night, Casey then receives a series of calls from a gravelly male voice. “Do you like scary movies?” he asks. She does. But when the voice becomes too creepy, even threatening, she hangs up. The calls continue, and Casey’s fear brings her to tears. Finally, she asks what the voice wants. “To see your insides,” he replies. Deathly afraid now, Casey responds to the phone’s persistent ringing with a surge of terror. She answers again, and the voice says he wants to play a game, then proceeds to quiz Casey on horror movie trivia. When she incorrectly responds to a question about Friday the 13th (1980), it leads to her boyfriend’s ghastly murder on the patio outside. Casey, too, meets her demise when a masked figure bursts into the house, chases her into the yard, and disembowels her within earshot of her parents, who have just arrived home. After several sequels, including years of repetitive plotting and increasingly elaborate backstory piled onto the Scream franchise, this bravura first scene still leaves audiences gasping for air. Along with the shower scene from Psycho (1960), it belongs on a shortlist of iconic and timeless sequences that transcend the films they inhabit.

Scream’s opener embodies how Craven and screenwriter Kevin Williamson took a knife to the slasher subgenre’s guts and dissected its insides. Horror movies would never be the same. Following the 1980s slasher heyday and its gradual decline by the early 1990s, the film at once deconstructs and embraces its formulas through in-jokes and self-reflexivity. The schema is a brilliant one, as the writer and director reinvent the material by adhering to the template they seek to anatomize. Indeed, Scream is more than just a horror movie; it’s also a genuinely keeps-you-guessing whodunit, a self-aware comedy, and a meta-commentary on slasher movies. Although the film wasn’t the first—or even Craven’s first—to explore horror through a postmodern lens, its popularity in 1996 and beyond launched one of the most successful horror franchises in film history. Regardless of what came afterward, the original’s influence on horror at large remains undeniable as a launchpad for the genre’s strain of self-referentiality. But often overlooked in discussions of Scream’s legacy is the harmonious marriage of Williamson’s script and Craven’s authorial perspective, which crystallizes themes present throughout Craven’s work: his tendency to start with conventional situations and build upon them; his standard use of unreliable authority figures; and more prominently, his lasting interest in the division between reality and dreams. In Scream’s case, movies supply an alternative to reality, and the film’s characters exist both within the movies and outside them.

Scream started from a script called Scary Movie, written by then-novice screenwriter Williamson, about teens who are aware of the slasher subgenre’s tropes yet cannot avoid falling into its clichés. Before becoming a screenwriter, Williamson studied theater, pursued a career as a New York actor, and then later moved to Los Angeles to appear in a few television shows while studying screenwriting at UCLA. He formed a business relationship with Miramax founders Bob and Harvey Weinstein after selling them his first script, called Killing Mrs. Tingle (later produced in 1999 under the studio’s genre offshoot Dimension Films with the title Teaching Mrs. Tingle). The Scary Movie script was inspired by a night when Williamson was house-sitting and watching a TV special about the Gainesville Ripper murders. He heard a strange noise, so he grabbed a butcher knife and called a friend, and they tested each other’s knowledge of horror movie trivia while he searched the house. The conversation inspired the first scene of Williamson’s story, which he wrote after locking himself in a Palm Springs hotel room to crank out the spec script. Williamson claims he wrote his Scary Movie script in three days, all while listening to the soundtrack of Halloween (1978) and thinking about the horror movies he watched as a teen.

Scream started from a script called Scary Movie, written by then-novice screenwriter Williamson, about teens who are aware of the slasher subgenre’s tropes yet cannot avoid falling into its clichés. Before becoming a screenwriter, Williamson studied theater, pursued a career as a New York actor, and then later moved to Los Angeles to appear in a few television shows while studying screenwriting at UCLA. He formed a business relationship with Miramax founders Bob and Harvey Weinstein after selling them his first script, called Killing Mrs. Tingle (later produced in 1999 under the studio’s genre offshoot Dimension Films with the title Teaching Mrs. Tingle). The Scary Movie script was inspired by a night when Williamson was house-sitting and watching a TV special about the Gainesville Ripper murders. He heard a strange noise, so he grabbed a butcher knife and called a friend, and they tested each other’s knowledge of horror movie trivia while he searched the house. The conversation inspired the first scene of Williamson’s story, which he wrote after locking himself in a Palm Springs hotel room to crank out the spec script. Williamson claims he wrote his Scary Movie script in three days, all while listening to the soundtrack of Halloween (1978) and thinking about the horror movies he watched as a teen.

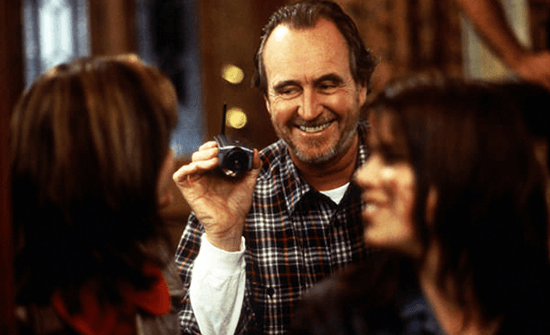

Williamson’s screenplay prompted a bidding war among Hollywood studios. Oliver Stone’s production company wanted the movie; so did Morgan Creek, Paramount, and Universal. But it was Bob Weinstein’s offer from Dimension Films that appealed to Williamson the most, scoring him $500,000, an agreement to write two more features, and a chance to direct. The screenwriter would later claim that he had already planned the first two sequels, complete with treatments for both; though, that claim has been disputed and may be self-mythologizing by the writer. As for a director of the newly retitled Scream, Miramax turned to Craven, who had been developing a remake for the studio of Robert Wise’s The Haunting (1963), based on Shirley Jackson’s novel, before they put the project into turnaround (it was later produced, disastrously so, by DreamWorks under the helm of Jan de Bont). However, Williamson’s script didn’t convince Craven initially. Since making his directorial debut with The Last House on the Left in 1972, Craven had yearned to place some distance between himself and the horror genre. Even though horror provided him with consistent work over the years, he wanted to expand his reach into other material. The director maintained this push-and-pull relationship with horror for most of his career.

Craven became a horror director somewhat by sheer happenstance. He grew up in a strict Evangelical Baptist household that barred him from watching any movies, apart from those released by Disney. This background left him rather sheltered until he studied English at Wheaton College, followed by graduate studies in writing and philosophy at Johns Hopkins University, where he peripherally learned about films and filmmaking. He taught for a short time, but he wasn’t interested in doctoral studies or academic life. On a whim, he purchased a 16 mm camera and began experimenting. Increasingly interested in filmmaking, Craven soon dropped teaching for a lowly position at a post-production house operated by a friend. There, he learned the technical side of making industrial films, such as sound and film editing. He even worked on assembling a number of pornographic movies, among them Deep Throat (1972), under assumed names, often alongside friend Sean S. Cunningham (director of Friday the 13th). After working with Cunningham on a few cheap skin flicks for American International Pictures, the company offered them a small budget to make a horror film, which could be made inexpensively and easily turn a profit. The result, The Last House on the Left (1972), burned itself onto the brain of moviegoers and critics with its docu-style scenes of exploitative violence and rape, which, Craven later claimed, intended to confront audiences with the reality of violence in the Vietnam War.

In the years to follow, Craven found himself inextricably associated with the horror genre, even though in press interviews he often expressed his desire to try other material. His second feature, The Hills Have Eyes (1977), a success about road-trippers who become prey to a cannibalistic family in Nevada, came five years later. It wasn’t until Craven revised the slasher subgenre with his 1984 hit, A Nightmare on Elm Street, that he earned a place among the era’s great horror filmmakers. Then an alternative take on the killer-in-a-mask trope that had dominated the horror market, Craven’s maniac, Freddy Krueger, did not invade the homes of his victims but their dreams, and he used a homemade glove with knives on the fingers as his weapon of choice. Craven would continue to offer pseudo-slasher alternatives with Shocker (1989) and The People Under the Stairs (1991), always rethinking the genre’s limitations and expanding them. Craven told author John Wooley, “The technique I like to use is to start with sort of clichéd situations or characters, where the beginning leads the audience to think, ‘Oh, we’re dealing with these standard-issue things.’ And then, to just keep adding complexity.” Oddly enough, Scream was Craven’s first horror film about a traditional masked killer. What is more, the film only superficially occupies the template where the slasher adds to their body count throughout the movie; rather, the film combines the slasher with a comic whodunit—a theme that carries through the sequels as well.

In the years to follow, Craven found himself inextricably associated with the horror genre, even though in press interviews he often expressed his desire to try other material. His second feature, The Hills Have Eyes (1977), a success about road-trippers who become prey to a cannibalistic family in Nevada, came five years later. It wasn’t until Craven revised the slasher subgenre with his 1984 hit, A Nightmare on Elm Street, that he earned a place among the era’s great horror filmmakers. Then an alternative take on the killer-in-a-mask trope that had dominated the horror market, Craven’s maniac, Freddy Krueger, did not invade the homes of his victims but their dreams, and he used a homemade glove with knives on the fingers as his weapon of choice. Craven would continue to offer pseudo-slasher alternatives with Shocker (1989) and The People Under the Stairs (1991), always rethinking the genre’s limitations and expanding them. Craven told author John Wooley, “The technique I like to use is to start with sort of clichéd situations or characters, where the beginning leads the audience to think, ‘Oh, we’re dealing with these standard-issue things.’ And then, to just keep adding complexity.” Oddly enough, Scream was Craven’s first horror film about a traditional masked killer. What is more, the film only superficially occupies the template where the slasher adds to their body count throughout the movie; rather, the film combines the slasher with a comic whodunit—a theme that carries through the sequels as well.

At the time Scream was offered to him, the director was finishing work on Vampire in Brooklyn (1995), a commercial and creative disaster that found Craven trying to strike a balance between horror and comedy, with no help from producer and star Eddie Murphy, who couldn’t decide what kind of vampire film it should be: funny or scary. Although Craven passed on Williamson’s script initially because he felt the material was too “extreme,” and too much of a pop-culture commentary that bordered on satire, his assistant Julie Plec, director of development Lisa Harrison, and longtime editor Patrick Lussier convinced him that the script could be scary. The exact reasons for Craven’s change of mind vary by account. Plec claims the Weinsteins offered an impossible-to-pass-up payday. Other accounts suggest he only seriously considered the material after the bidding war and Drew Barrymore’s subsequent casting, which implied that people saw something special in the material, so he shouldn’t pass it up. Production designer Bruce Alan Miller observed that Craven came to see the script less as a horror movie than a murder mystery, which appealed to him. At the time, Craven claimed he resolved to make Scream as a swan song to his horror career, not realizing that he would make three more entries in the franchise—not to mention several other horror movies, including Cursed (2005) and My Soul to Take (2009)—in the years to follow.

Whatever his reasons, Craven signed on and, despite his initial hesitance, made a film that aligns with his directorial obsessions. For a script authored by Williamson, Scream occupies many themes evident in Craven’s body of work. Even Williamson’s signature meta dialogue and self-reflexive commentaries on the horror genre—present in Williamson’s later scripts for The Faculty (1998) and Cursed—had been anticipated by Craven’s earlier work. Just two years before Scream arrived in theaters, Wes Craven’s New Nightmare (1994) deconstructed the franchise that began with the writer-director’s A Nightmare on Elm Street. After five sequels released by New Line Cinema, known as “The House That Freddy Built,” thanks to their success, Craven’s script put himself and the original actors into a self-referential revamp that comments on the franchise while reinventing it. New Nightmare also remarks on the state of horror, Hollywood deal brokering, exploitation on and offscreen, and celebrity in a film that winks at the audience. Although the result became only a mild box-office success, New Nightmare reaffirmed Craven’s long-held interest in the dichotomy between two worlds: not only reality and the dreams haunted by Freddy Krueger, but also reality and the movies—the stuff dreams are made of, produced within the so-called Dream Factory of Hollywood.

Even though Williamson received sole screen credit for the Scream script, Craven contributed ideas as well. “The moment I signed on, I’m writing notes, outlines, whatever I can to help the process,” said Craven, quoted in author Brian J. Robb’s book about the director’s career. “Kevin and I collaborated a great deal.” After all, both Craven and Williamson relished how their characters occupy and defy slasher movie clichés. The characters quote classics of the horror genre, and not a scene goes by without some passing reference or visual gag about movies or television, demonstrating the mediated culture of the 1990s. Craven recognized that, after almost three decades in the genre, “I can’t just continue to do straight horror films. You don’t see all these conventions and clichés without imitating yourself. You have to at least let the audience know you’re aware of it.” While Craven and Williamson recognized that such formulas have been overused, they remained a necessary platform on which to innovate. And yet, though Williamson’s script adheres to slasher clichés as the body count rises, and even though the director didn’t see the film as a straightforward slasher movie, Craven’s desire to make “one more to-the-wall horror film” heightened the intensity of the screen violence. He also emphasizes Scream’s characteristic as a “sophisticated murder mystery dealing with kids in real life.”

Even though Williamson received sole screen credit for the Scream script, Craven contributed ideas as well. “The moment I signed on, I’m writing notes, outlines, whatever I can to help the process,” said Craven, quoted in author Brian J. Robb’s book about the director’s career. “Kevin and I collaborated a great deal.” After all, both Craven and Williamson relished how their characters occupy and defy slasher movie clichés. The characters quote classics of the horror genre, and not a scene goes by without some passing reference or visual gag about movies or television, demonstrating the mediated culture of the 1990s. Craven recognized that, after almost three decades in the genre, “I can’t just continue to do straight horror films. You don’t see all these conventions and clichés without imitating yourself. You have to at least let the audience know you’re aware of it.” While Craven and Williamson recognized that such formulas have been overused, they remained a necessary platform on which to innovate. And yet, though Williamson’s script adheres to slasher clichés as the body count rises, and even though the director didn’t see the film as a straightforward slasher movie, Craven’s desire to make “one more to-the-wall horror film” heightened the intensity of the screen violence. He also emphasizes Scream’s characteristic as a “sophisticated murder mystery dealing with kids in real life.”

The casting of those “kids” would be vital to Scream’s popularity. Craven was determined to avoid filling out the cast with anonymous names and faces, as many horror movies do. Barrymore’s presence as the first-cast actor set the standard. After years as a child performer, Barrymore entered the 1990s in several rebellious sexpot roles, including Poison Ivy (1992) and Batman Forever (1995). And her iconic presence in Scream wouldn’t be the first time she had cameoed in a horror movie—in 1992’s Waxwork II: Lost in Time, she appears briefly as a victim of Nosferatu. But her role as Casey would prove as iconic as Janet Leigh in Psycho. Neve Campbell had become popular thanks to TV’s Party of Five, as well as her first major movie role in The Craft, released just a few months before Scream in May. Skeet Ulrich also appeared in The Craft to lesser effect. Craven cast Ulrich for his resemblance to Johnny Depp, to whom the director gave his big break on A Nightmare on Elm Street. David Arquette had a recognizable face from mostly comedic roles in TV and movies, along with a memorable turn in Walter Hill’s Wild Bill (1995) as Jack McCall, killer of Wild West legend Wild Bill Hickok. Courteney Cox had become a household favorite thanks to a recurring role on Family Ties, the box-office hit Ace Ventura: Pet Detective (1994), and the sitcom Friends. Matthew Lillard, too, made waves after costarring in Hackers (1996), while Rose McGowan had appearances in a pair of Pauly Shore comedies. Altogether, Scream was filled with names and faces audiences would recognize.

The opening sequence gives way to scenes in your typical horror movie high school, complete with twentysomethings playing teens who spend almost no time in class. Within this milieu, Craven could explore his recurrent interest in absent or unreliable parents, ineffectual cops, and broken families—all factors that isolate the teen characters. Among them, virginal student Sidney Prescott (Campbell) dwells on the murders of Casey and Steve, as nearly a year ago, her mother was raped and murdered in almost the same manner. But her initially supportive boyfriend, Billy (Ulrich), proves too sexually frustrated to be understanding. On the periphery are Sidney’s friends, Tatum (McGowan) and Stu (Lillard). McGowan turns Tatum into an archetypal snarky best friend role, while Lillard’s cartoonish over-acting hints at something unhinged behind his saliva-spewing line delivery and altogether wired screen presence that, upon revisiting the movie, provides an all-too-apparent clue to the third-act twist. A fifth wheel, Jamie Kennedy provides some laughs as Randy, the resident video store clerk and movie geek whose vast knowledge of horror movie survival rules (don’t have sex; don’t drink or do drugs; never say, “I’ll be right back”) goes unheeded and openly debated.

At the same time, Gale Weathers (Cox), a nosy local reporter who will do anything for ratings, accompanied by her snack-centric cameraman Kenny (W. Earl Brown), hopes to uncover a connection between the new murders and Sidney’s mother’s death. Though Sidney already testified and helped convict her mother’s supposed killer, Cotton Weary (Liev Schreiber), Gale believes Sidney was mistaken—that the latest rash of killings, conducted by someone wearing a “Father Death” costume, proves Weary’s innocence. Tatum’s older brother, Dewey (Arquette), a hapless deputy, tries to shield Sidney from Weathers, but he’s boyishly smitten with Gale and eventually caught in a dopey romance (echoed in Cox and Arquette’s offscreen coupling). Meanwhile, as Randy observes, “Everyone’s a suspect!” But Randy’s obsession with movie trivia makes him a perfect candidate. Then again, maybe the killer is Principal Himbry (Henry Winkler), whose loudspeaker broadcasts contain creepily intimate sentiments (“Remember that your principal loves you”)—though, later, he threatens students with scissors when they play a cruel joke in the “Father Death” mask. It could also be Billy, who is quick to make references to The Exorcist (1973) and wants to advance his relationship with Sidney beyond the “edited for television” stage. Or maybe it’s Sidney’s father, Neil (Lawrence Hecht), who conveniently goes on a business trip when the killings start. Could he be playing out some murderous game on the one-year anniversary of his wife’s death?

At the same time, Gale Weathers (Cox), a nosy local reporter who will do anything for ratings, accompanied by her snack-centric cameraman Kenny (W. Earl Brown), hopes to uncover a connection between the new murders and Sidney’s mother’s death. Though Sidney already testified and helped convict her mother’s supposed killer, Cotton Weary (Liev Schreiber), Gale believes Sidney was mistaken—that the latest rash of killings, conducted by someone wearing a “Father Death” costume, proves Weary’s innocence. Tatum’s older brother, Dewey (Arquette), a hapless deputy, tries to shield Sidney from Weathers, but he’s boyishly smitten with Gale and eventually caught in a dopey romance (echoed in Cox and Arquette’s offscreen coupling). Meanwhile, as Randy observes, “Everyone’s a suspect!” But Randy’s obsession with movie trivia makes him a perfect candidate. Then again, maybe the killer is Principal Himbry (Henry Winkler), whose loudspeaker broadcasts contain creepily intimate sentiments (“Remember that your principal loves you”)—though, later, he threatens students with scissors when they play a cruel joke in the “Father Death” mask. It could also be Billy, who is quick to make references to The Exorcist (1973) and wants to advance his relationship with Sidney beyond the “edited for television” stage. Or maybe it’s Sidney’s father, Neil (Lawrence Hecht), who conveniently goes on a business trip when the killings start. Could he be playing out some murderous game on the one-year anniversary of his wife’s death?

Given that Williamson’s script has all the misdirection and entrenched backstory of an Agatha Christie murder mystery, one couldn’t be faulted for arguing that Scream has more in common with a whodunit than a slasher movie. But the script offers clues aplenty to the identity of the killers, the subtly queer-coded Billy and Stu, starting early in the proceedings when Gus Black’s acoustic cover of “Don’t Fear the Reaper” plays over Sidney and Billy, the resident reaper, making out in her bedroom. Later, Stu’s motivation becomes apparent when Randy notes that Casey dumped Stu for her new boyfriend, Steve, and both became victims. Ironically, Randy, while talking to Stu at Blockbuster Video around the film’s midpoint, outlines his theory that Billy makes the most likely prime suspect and Sidney’s father is merely a red herring—and he’s absolutely right. However, it’s rather unclear why Billy and Stu target Principal Himbry and Tatum, other than to increase the film’s body count. In that sense, Williamson’s story doesn’t have the same tightly wound logic of a Christie novel, splitting its energies between a whodunit template and a slasher. Though, the screenwriter shows more interest in commenting on the slasher subgenre than the whodunit when Sidney famously mocks that horror movies are all the same: “It’s always some stupid killer stalking some big-breasted girl, who can’t act, who always runs up the stairs when she should be going out the front door. They’re ridiculous.”

If one thing remains true of Scream and its sequels, it’s that the “Father Death” mask resulted in the iconic look of the franchise, despite its origins as a Halloween mask created in 1991 by Fun World, a novelties company established in 1959. Williamson’s script had no input about how the mask might look, and producer Marianne Maddalena discovered the Fun World mask by chance while scouting locations. Designed by Brigitte Sleiertin, the mask—originally named “The Peanut-Eyed Ghost” for the distinct shape of its eyes—is often said to evoke Edvard Munch’s famed 1893 painting The Scream. Rather, Sleiertin’s design was inspired by the ghost in the 1933 Betty Boop cartoon Snow White. Craven and Miramax negotiated with Fun World to gain the rights to their mask, and they agreed, realizing it would doubtlessly lead to more sales. Memorably voiced by animation regular Roger L. Jackson, Ghostface was played by stuntman Dane Farwell for much of the film, with Craven donning the costume for some of the opening sequence. As for the name, Tatum coins the term “Ghostface” when the killer isolates her in the garage at Stu’s party, the site of the film’s climactic scenes. Tatum wanders into the garage to get more beer, but the killer, credited in the script as “Ghost Masked Figure” or just “Figure” corners her. “No, please don’t kill me, Mr. Ghostface,” Tatum jokes. “I want to be in the sequel.” But Tatum doesn’t make it to the sequel or even out of the garage.

Tatum’s reaction becomes characteristic of Scream’s sly critique of mediated culture. Although the film teems with pop-culture references, the critique resides just under the surface of Williamson’s script, which acknowledges that living exclusively in the realm of films equates to a reality distortion field—at least for Billy and Stu. Their reality exists in the movies. Though their motivations may be personal—they killed Sidney’s mother, Maureen, a year earlier because she had an affair with Billy’s dad, prompting his parents to separate—their methods and perspectives are purely cinematic. Note how they expect their murderous plot to unfold like a horror movie and react with surprise when it doesn’t. To appear like victims in their frame-up of Sidney’s father, they stab each other, but Stu seems shocked when it hurts and bleeds more than expected. He becomes woozy and starts to lose consciousness, reacting with surprise that he’s so badly injured. Still, Williamson is careful not to turn Scream into a condemnation of horror or the film industry, avoiding any rhetoric that might argue in favor of censorship—that movies warp young and impressionable minds. “Movies don’t create psychos,” Billy declares. “Movies just make psychos more creative.”

Tatum’s reaction becomes characteristic of Scream’s sly critique of mediated culture. Although the film teems with pop-culture references, the critique resides just under the surface of Williamson’s script, which acknowledges that living exclusively in the realm of films equates to a reality distortion field—at least for Billy and Stu. Their reality exists in the movies. Though their motivations may be personal—they killed Sidney’s mother, Maureen, a year earlier because she had an affair with Billy’s dad, prompting his parents to separate—their methods and perspectives are purely cinematic. Note how they expect their murderous plot to unfold like a horror movie and react with surprise when it doesn’t. To appear like victims in their frame-up of Sidney’s father, they stab each other, but Stu seems shocked when it hurts and bleeds more than expected. He becomes woozy and starts to lose consciousness, reacting with surprise that he’s so badly injured. Still, Williamson is careful not to turn Scream into a condemnation of horror or the film industry, avoiding any rhetoric that might argue in favor of censorship—that movies warp young and impressionable minds. “Movies don’t create psychos,” Billy declares. “Movies just make psychos more creative.”

Billy and Stu’s detachment from reality finds them producing a movie reality of their own making, except no diegetic cameras capture the action. Once they confront Sidney in the climactic scenes and reveal their master plan in true Scooby-Doo format, their mediated worldviews become disturbingly apparent. To plan their scheme, they “just watched a few movies, took a few notes,” and applied some homespun movie magic: Billy manufactures a stunt fall down the stairs, and they used the corn syrup fake blood formula from Brian De Palma’s Carrie (1976). They even intend a follow-up: “We get to carry on and plan the sequel,” Stu proclaims. “Let’s face it, these days, you gotta have a sequel.” Sidney tries to rationalize with them: “This is life. This isn’t a movie.” But Billy affirms, “Sure it is, Sid. It’s all a movie. Life’s one great big movie.” Williamson’s script cleverly folds over on itself, remarking on Billy and Stu’s movie saturation yet supplying a cinematic resolution. Just before Sidney gets the upper hand and kills Stu, he tells her, “I always had a thing for ya, Sid.” She responds, “In your dreams,” and pushes a television onto his head—her actions suggesting that perhaps Stu’s dreams and screen entertainment are inseparable, and his dreamlike movie logic will be his downfall. The same is true of Billy, who’s shot by Gale and believed dead, only to fulfill Randy’s promise that slashers always have one last stinger. All at once, Billy jolts up. Sidney shoots him in the head. Only our hero, Sidney, defies the genre expectations. She may be a virginal final girl, but she breaks the virgin rule, has sex with Billy during Stu’s party, yet survives in the end.

Throughout his career, Craven’s dominant thematic concern is the separation between reality and other unreal worlds. In his most popular films, he explores the boundaries between real and more pliable realities (dreams, religion, television, cinema, etc.). For instance, Craven sought to depict unromanticized violence in The Last House on the Left to address the reality of the Vietnam War, therein identifying how most Hollywood violence is escapist entertainment and therefore a fantasy. Most famously in A Nightmare on Elm Street, Craven explored the opposing realms of reality and dreams with an entire film that takes place in a demonic dreamscape—a surreal rubber reality where anything can happen. The same quality pervades The Serpent and the Rainbow (1988), a highly fictionalized “true” account that weighs the science and mysticism behind the Haitian zombie. In Shocker, the slasher-style killer is a TV repairman who can move inside electricity, television airwaves, and others’ bodies, giving Craven a chance to explore how fantasy can bleed into reality. For the killers in Scream, their dreamlike perspective derives from an oversaturation in movie culture—a non-reality that prompts them to behave like horror movie characters.

In many of his films, Craven sought to underscore the distinction between reality and cinematic fantasy to emphasize the brutality of real-life violence. The director claims he sought to make violence realistic and unpleasant, and he couldn’t stomach audiences “getting off” on depictions of violence. He even admitted to walking out of Reservoir Dogs (1992) because he felt director Quentin Tarantino enjoyed filming the violence too much. So Craven’s output features violent scenes that either embrace the disturbing reality of violence or distinguish between reality and dreams, projections, and mimesis. Craven is not always successful in this ambition; he has delivered scenes of screen violence that prove thrilling or even fun, particularly in Cursed or the Scream sequels. But the deaths in Scream prove brutal and unflinching—signaled by Casey’s disembowelment in the opening scene and, extratextually, by killing off the most recognizable face among the ensemble (Barrymore). The violence suggests no one is safe and reinforces the aspect of Scream’s commentary on the genre. However, even while Craven and Williamson point out the potential dangers of being unable to discern reality from cinema, they’re not opposed to experimenting with the dynamic between reality and cinema in playful ways—to the extent that Scream spends much of its runtime on postmodern humor.

In many of his films, Craven sought to underscore the distinction between reality and cinematic fantasy to emphasize the brutality of real-life violence. The director claims he sought to make violence realistic and unpleasant, and he couldn’t stomach audiences “getting off” on depictions of violence. He even admitted to walking out of Reservoir Dogs (1992) because he felt director Quentin Tarantino enjoyed filming the violence too much. So Craven’s output features violent scenes that either embrace the disturbing reality of violence or distinguish between reality and dreams, projections, and mimesis. Craven is not always successful in this ambition; he has delivered scenes of screen violence that prove thrilling or even fun, particularly in Cursed or the Scream sequels. But the deaths in Scream prove brutal and unflinching—signaled by Casey’s disembowelment in the opening scene and, extratextually, by killing off the most recognizable face among the ensemble (Barrymore). The violence suggests no one is safe and reinforces the aspect of Scream’s commentary on the genre. However, even while Craven and Williamson point out the potential dangers of being unable to discern reality from cinema, they’re not opposed to experimenting with the dynamic between reality and cinema in playful ways—to the extent that Scream spends much of its runtime on postmodern humor.

To be sure, Scream is a horror movie about horror movies—specifically those in the slasher subgenre, but also about movie watching and trivia in general. Nods to Universal’s 1931 Frankenstein give way to discussions about Jamie Lee Curtis’ “scream queen” presence in Prom Night to Terror Train (both from 1980). Tatum mentions those “Wes Carpenter” films with disdain, as Craven is sometimes bucketed with director John Carpenter, since both have created iconic screen killers. Billy questions why Hannibal Lecter eats people or why Norman Bates needed to kill at all, while Sidney wishes her life was more like a Meg Ryan movie. Horror movie icon Linda Blair appears in a brief cameo; so does Frances Lee McCain, who played the mom in Gremlins (1985), as Tatum and Dewey’s mother. Craven pokes fun at himself as well. References to A Nightmare on Elm Street occur throughout. In the opening sequence, the voice on the phone remarks how Craven’s original Freddy Krueger movie was scary. “Well, the first one was, but the rest sucked,” Casey replies, as if in defense of Craven. The high school also employs a janitor, named Fred (Craven), who dons Krueger’s signature red and green sweater and dirty brown hat. And as intended, Billy is a dead ringer for Johnny Depp, who in the 1984 film played a boyfriend who climbs through his girlfriend’s bedroom window as Billy does. Notably, there’s even an unscripted nod to Clueless when Randy says, “As if,” referencing Alicia Silverstone’s Cher. Released the year before, Amy Heckerling’s teen comedy, like Scream, has the rare ability to straddle the line between postmodern satire and straightforward genre exercise.

However, Scream is more than a reference machine, and Craven’s skilled direction enhances Williamson’s writing. “I think I brought a lot to the film,” said Craven. “There were a lot of improvisations and physical staging of a lot of scenes [that were] very different to the way they’d been scripted.” The director worked with cinematographer Mark Irwin to create fluid, extended takes accented by lens flares, manic chases upstairs and through houses, and Dutch angles that lend the material a distinct, heightened appearance. But Craven faced a battle with the MPAA over his signature intensity—a tonal quality that cannot be corrected by removing a scene or two. Craven remarked that the censors called the film “Too loud, too frightening, too scary.” But wasn’t that the point? Following a long battle that left Craven exhausted (“After this episode with the MPAA, I feel like my days are numbered in this genre, because they’re just on me,” he lamented), the censors finally granted Scream an R rating. If some of the guts had been removed, Craven’s essential visual style remained, enhancing the thrills and occasional shocks, while the use of music and aural jump-scares manipulate the viewer. Marco Beltrami’s punchy electronic score and sound design rattle the audience with jolting booms, thumps, and screams on the soundtrack, each prompting an involuntary reaction. But the director deploys such tricks with an awareness of their history. Watch the abrupt cut when Sidney departs the school bus for home, prompting a mild jump-scare from the unexpected sound of the bus’ hydraulic brakes—a callback to how the original Cat People invented the jump-scare, once called “buses,” after a similar bus scene in that 1942 Val Lewton production.

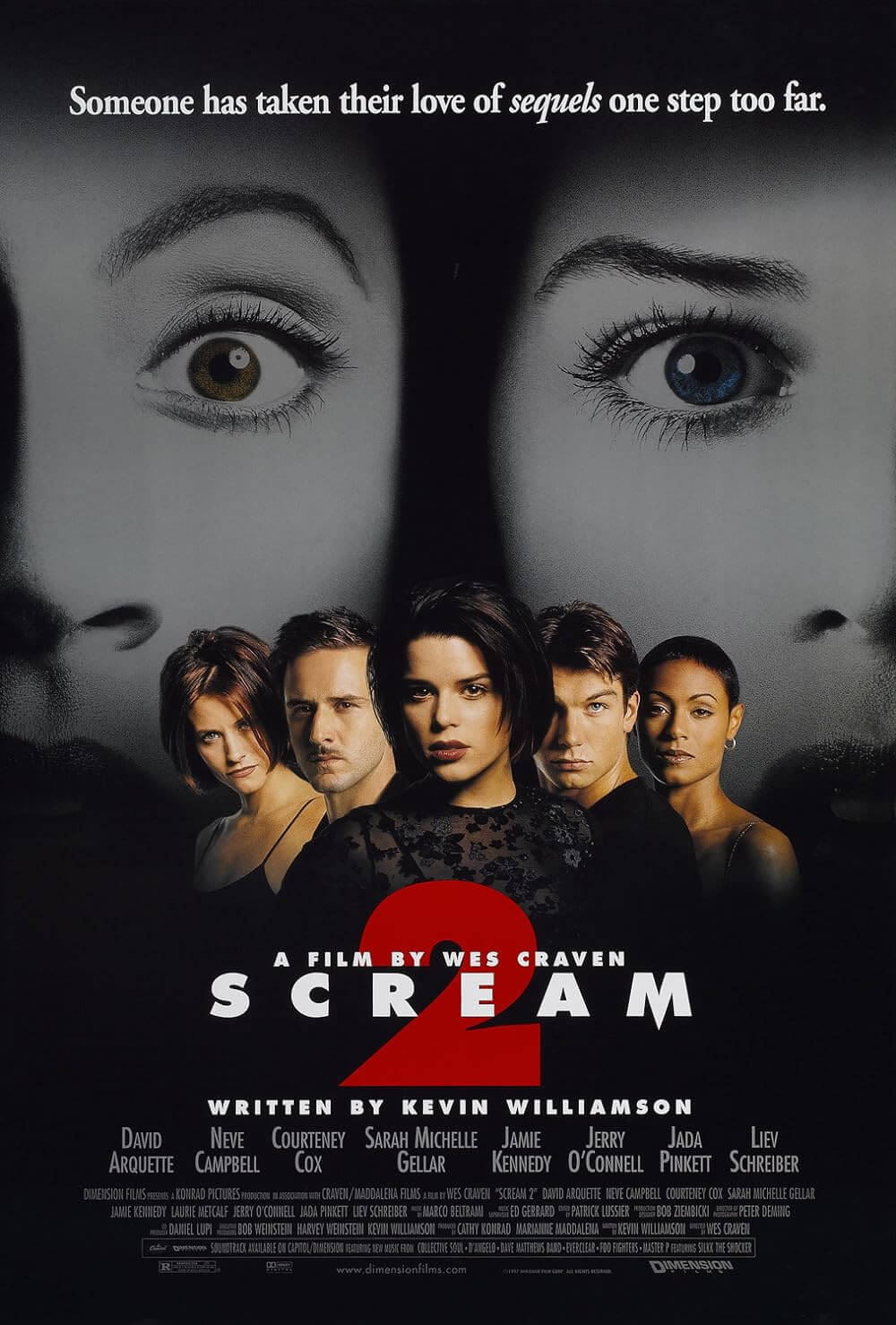

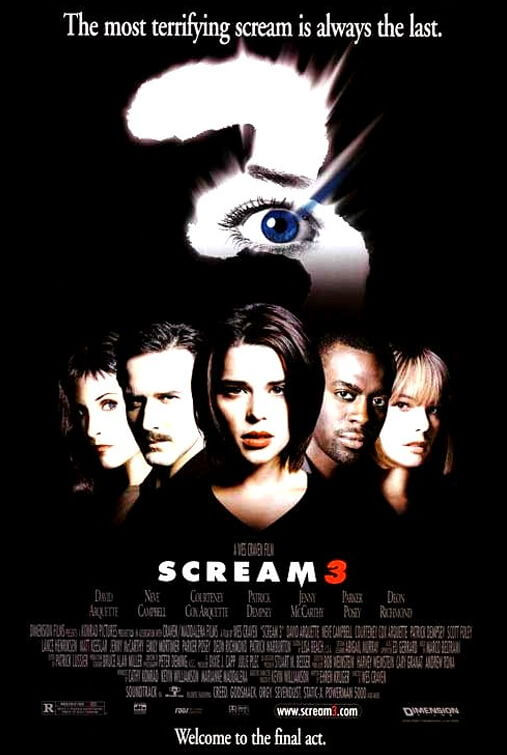

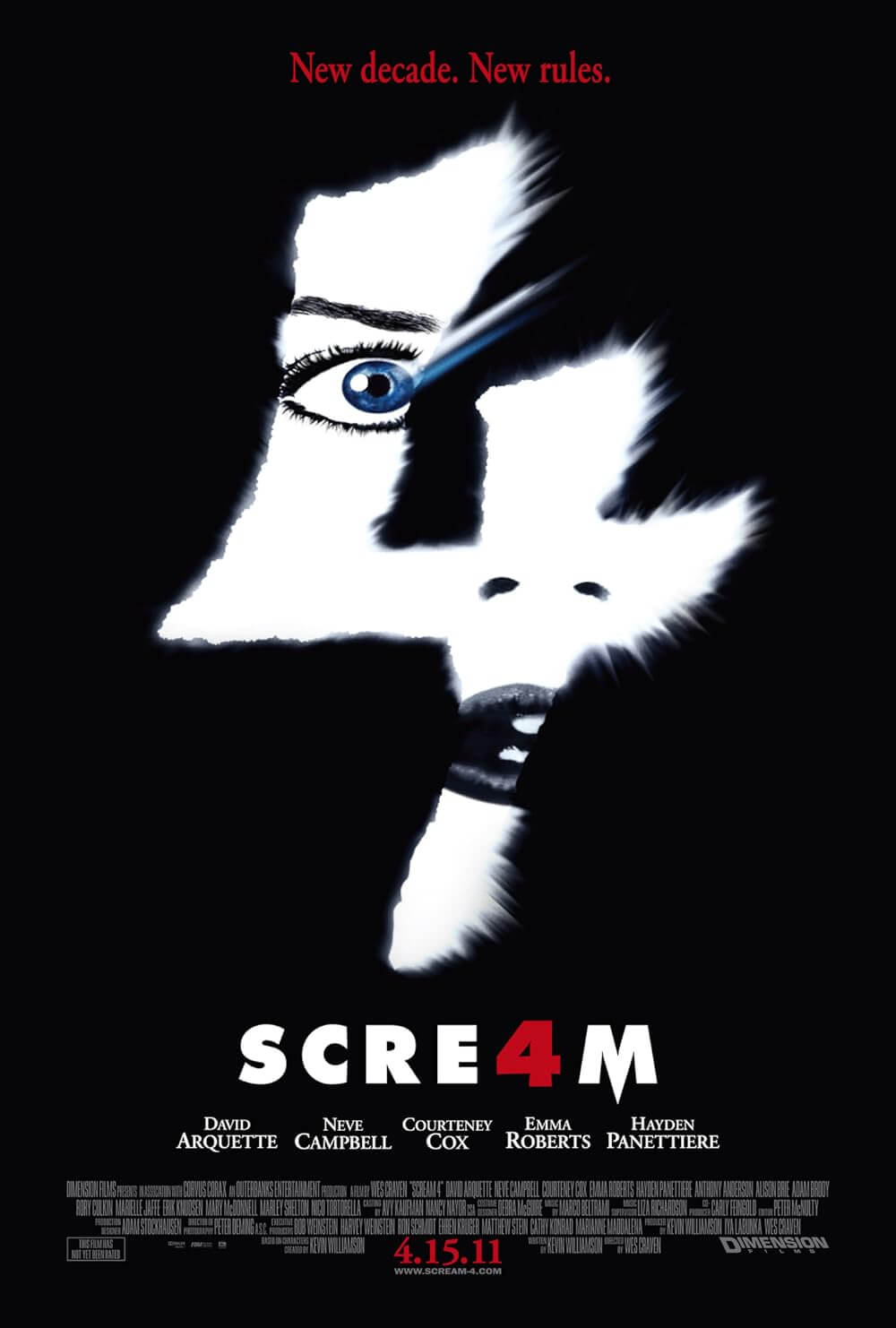

Scream opened on December 20, 1996, to a modest weekend box-office take, only to slowly gain an audience after positive reviews and word-of-mouth spread. While most horror movies usually last in the theater for a few weekends at most, Craven’s film survived until the following June, passing $100 million in domestic grosses on a $14 million budget and becoming Dimension’s biggest performer. While Scream saturated the cultural zeitgeist—prompting the ironically titled Scary Movie parody series in 2000—Miramax sought to replicate their success. The late 1990s would bring a handful of Williamson’s knowing horror movies to the screen, including I Know What You Did Last Summer (1997) and The Faculty (1998). The studio also negotiated with Craven to direct Scream 2 and Scream 3 (1997 and 2000, respectively), granting him a non-horror-related project in their proposed three-picture deal. The result, the critically acclaimed box-office flop Music of the Heart, starring Meryl Streep and Angela Bassett, marked the only serious drama to his credit. Eventually, Craven would return for Scream 4 in 2011, his final outing as director. Yet, despite the varying quality of the sequels, Scream would remain arguably Craven’s finest in an impressive career of landmark films.

Scream opened on December 20, 1996, to a modest weekend box-office take, only to slowly gain an audience after positive reviews and word-of-mouth spread. While most horror movies usually last in the theater for a few weekends at most, Craven’s film survived until the following June, passing $100 million in domestic grosses on a $14 million budget and becoming Dimension’s biggest performer. While Scream saturated the cultural zeitgeist—prompting the ironically titled Scary Movie parody series in 2000—Miramax sought to replicate their success. The late 1990s would bring a handful of Williamson’s knowing horror movies to the screen, including I Know What You Did Last Summer (1997) and The Faculty (1998). The studio also negotiated with Craven to direct Scream 2 and Scream 3 (1997 and 2000, respectively), granting him a non-horror-related project in their proposed three-picture deal. The result, the critically acclaimed box-office flop Music of the Heart, starring Meryl Streep and Angela Bassett, marked the only serious drama to his credit. Eventually, Craven would return for Scream 4 in 2011, his final outing as director. Yet, despite the varying quality of the sequels, Scream would remain arguably Craven’s finest in an impressive career of landmark films.

Besides the unforgettable opening, the key post-modern sequence in Scream’s self-aware adoption of horror clichés involves Randy, drunk and watching Halloween (1978) alone at Stu’s party. During the scene where the masked Michael Myers approaches Jamie Lee Curtis from behind, Randy shouts at the screen, “Jamie, turn around!” Meanwhile, Ghostface approaches Randy from behind, leaving the audience, and Kenny in the news van, to shout for Jamie Kennedy to observe his character’s warning. The scene is a précis, illustrating the self-referential layers permeating the film—how movie-savvy characters identify and try to avoid obvious horror movie mistakes, but they make them anyway; how the audience remains aware of the clichés, which work despite their familiarity. Under the ensuing pile of dead teenagers is a revisionist experience that has stood the test of time. Craven and Williamson offer a nimble, wildly entertaining, and even sophisticated reconsideration of slasher movies that, for better or worse, led to an age of meta-horror. But no matter how often Scream has been emulated by its sequels and imitators, none match the film’s delicate balance of commenting on horror movies by innovating within the genre’s confines.

(Note: This essay was suggested and commissioned on Patreon and published on February 23, 2023.)

Bibliography:

Maroney, Padriac. It All Began with a Scream. BearManor Media, 2021.

Robb, Brian J. Screams and Nightmares: The Films of Wes Craven. Polaris Publishing, Inc., 2022.

Wooley, John. Wes Craven: The Man and His Nightmares. John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 2011.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review